Transylvanian Diet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Transylvanian Diet (german: Siebenbürgischer Landtag; hu, erdélyi országgyűlés; ro, Dieta Transilvaniei) was an important legislative, administrative and judicial body of the

A separate royal official, the

A separate royal official, the

General assemblies of the noblemen from one or more counties developed into important forums of the administration of justice in the entire Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century.

General assemblies of the noblemen from one or more counties developed into important forums of the administration of justice in the entire Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century.

Transylvania was mentioned as a ''regnum'' (or realm) in royal charters already in the second half of the 13th century. When writing of the ''regnum Transylvanum'', the royal charters initially referred to the Transylvanian noblemen who formed a closed community "bound together by certain reciprocal rights and duties". The Székely and Saxon communities were included in the concept only after the confirmation of the Union of the Three Nations in 1459. The '' Tripartitum''the compendium of the customary law of Hungary, completed in 1514explicitly acknowledged that Transylvania was a separate realm, with her own peculiar customs, but it also emphasized that Transylvania was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The laws of the Kingdom of Hungary were to be applied in Transylvania and the decisions of the royal courts of justice were also to be obeyed in the province.

The

Transylvania was mentioned as a ''regnum'' (or realm) in royal charters already in the second half of the 13th century. When writing of the ''regnum Transylvanum'', the royal charters initially referred to the Transylvanian noblemen who formed a closed community "bound together by certain reciprocal rights and duties". The Székely and Saxon communities were included in the concept only after the confirmation of the Union of the Three Nations in 1459. The '' Tripartitum''the compendium of the customary law of Hungary, completed in 1514explicitly acknowledged that Transylvania was a separate realm, with her own peculiar customs, but it also emphasized that Transylvania was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The laws of the Kingdom of Hungary were to be applied in Transylvania and the decisions of the royal courts of justice were also to be obeyed in the province.

The

Principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) can either be a monarchical feudatory or a sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a regnant-monarch with the title of prince and/or princess, or by a monarch with another title considered to fall un ...

(from 1765 Grand Principality) of Transylvania between 1570 and 1867. The general assemblies of the Transylvanian noblemen

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

and the joint assemblies of the representatives of the "Three Nations of Transylvania

Unio Trium Nationum (Latin for "Union of the Three Nations") was a pact of mutual aid codified in 1438 by three Estates of Transylvania: the (largely Hungarian) nobility, the Saxon (German) patrician class, and the free military Székelys.

The un ...

"the noblemen, Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

and Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

gave rise to its development. After the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

in 1541, delegates from the counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

of the eastern and northeastern territories of Hungary proper (or Partium) also attained the Transylvanian Diet, transforming it into a legal successor of the medieval Diets of Hungary.

The diet sessions at Vásárhely (now Târgu Mureş) (20 January 1542) and at Torda (now Turda

Turda (; hu, Torda, ; german: link=no, Thorenburg; la, Potaissa) is a city in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in the southeastern part of the county, from the county seat, Cluj-Napoca, to which it is connected by the Europ ...

) (2 March 1542) laid the basis for the political and administrative organization of Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

. The diet decided on juridical, military and economic matters. It ceased to exist following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hunga ...

.

Background

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

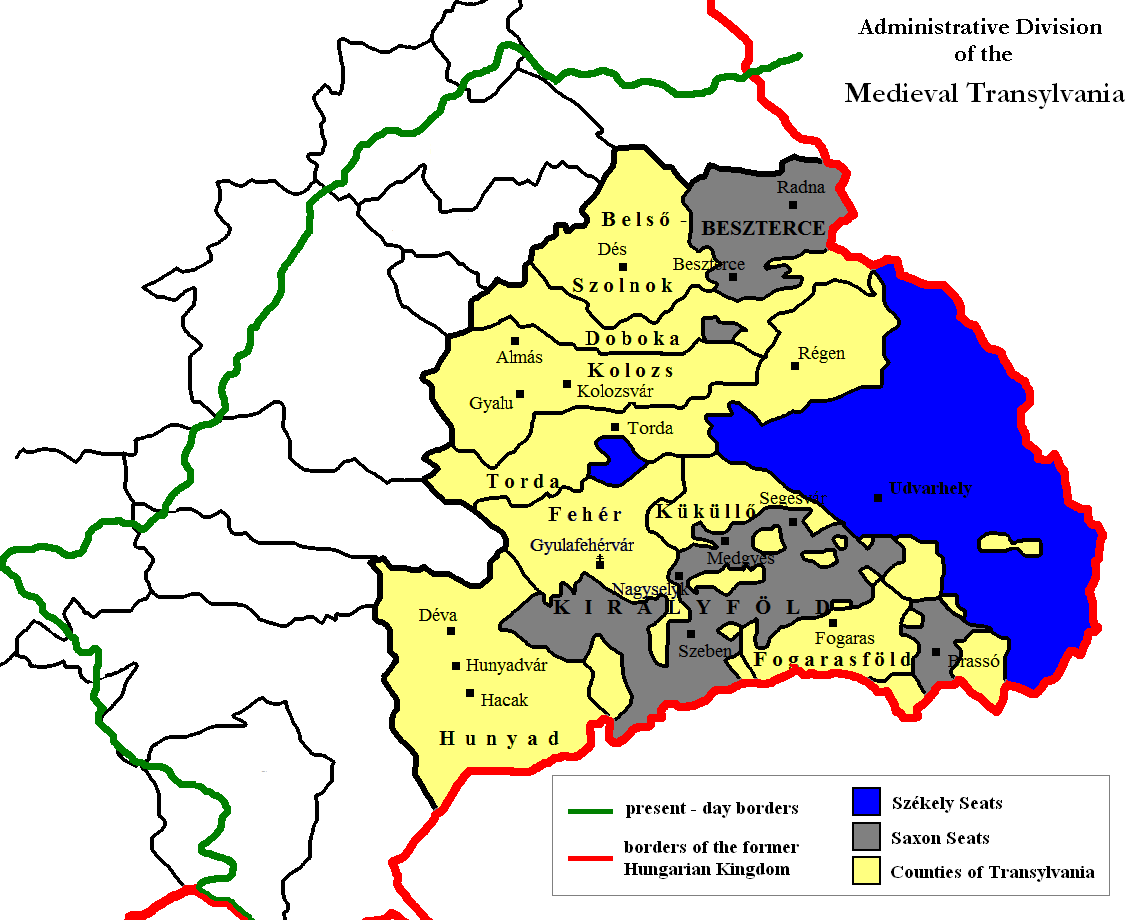

("Land beyond the Forests") was a borderland in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

. The development of royal administration is documented from the second half of the 11th century. The royal castle at Torda (now Turda

Turda (; hu, Torda, ; german: link=no, Thorenburg; la, Potaissa) is a city in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in the southeastern part of the county, from the county seat, Cluj-Napoca, to which it is connected by the Europ ...

in Romania) was first mentioned in 1075, the fortress at Küküllő (now Cetatea de Baltă in Romania) in 1177. Most royal castles developed into the seats of counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, which were important administrative units, each named for its center. A high-ranking royal official, the voivode

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the me ...

was the superior of the ''ispán

The ispánRady 2000, p. 19.''Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517)'', p. 450. or countEngel 2001, p. 40.Curta 2006, p. 355. ( hu, ispán, la, comes or comes parochialis, and sk, župan)Kirs ...

s'' (or heads) of the Transylvanian counties Doboka, Fehér, Hunyad

Hunyad (today mainly Hunedoara) was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary, of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and of the Principality of Transylvania. Its territory is now in Romania in Transylvania. The capital of the co ...

, Kolozs, Kraszna, Küküllő and Torda. from the late 12th century.

Count of the Székelys

The Count of the Székelys ( hu, székelyispán, la, comes Sicolorum) was the leader of the Hungarian-speaking Székelys in Transylvania, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. First mentioned in royal charters of the 13th century, the counts were ...

, lead the Hungarian-speaking Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

from the 1220s. The Székelys had moved from other regions of the kingdom to Transylvania and formed a community of free warriors. Their administrative units were known as " seats" from the 14th century. The seats Udvarhelyszék, Csíkszék, Sepsiszék, Orbaiszék, Kézdiszék, Marosszék and Aranyosszék

Aranyos seat ( hu, Aranyosszék; la, Sedes Aurata; ro, Scaunul Arieșului)Attila M. Szabó: Historical and Administrative Toponymy of Transylvania, the Banat and Partium. Miercurea-Ciuc, 2003, pp. II/1079-80. was the seat (territorial administrat ...

. were headed by elected officials. The Székelys initially held their lands in common. However, disparity between wealthy and poor Székelys grew, enforcing royal legislation to acknowledge the existence of Székely groups of diverse status in 1473. Thereafter, only the wealthiest Székelys fought in the royal army on horse; those who could only fight as foot-soldiers started to lose their political rights.

The ancestors of the Transylvanian Saxons

The Transylvanian Saxons (german: Siebenbürger Sachsen; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjer Såksen''; ro, Sași ardeleni, sași transilvăneni/transilvani; hu, Erdélyi szászok) are a people of German ethnicity who settled in Transylvania ( ...

settled in the southern and north-eastern regions in the 11th and 12th centuries. In 1224, Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II ( hu, II. András, hr, Andrija II., sk, Ondrej II., uk, Андрій II; 117721 September 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1205 and 1235. He ruled the Principality of Halych from 11 ...

granted privileges to the Saxons who inhabited southern Transylvania, putting them under the authority of a royal official, the Count of Hermannstadt The Count of Hermannstadt, also Count of Sibiu or Count of Szeben ( hu, szebeni ispán), was the head of the Transylvanian Saxons living in the wider region of Hermannstadt (now Sibiu in Romania) in the 13th and early 14th centuries. The counts were ...

, and authorizing them to freely elect their local leaders. After a Saxon rebellion, Charles I of Hungary

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert ( hu, Károly Róbert; hr, Karlo Robert; sk, Karol Róbert; 128816 July 1342) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou and the only son of ...

abolished the office of the Count of Hermannstadt and appointed royal judges to head the Saxon districts in 1324. However, the wealth of the Saxon merchants, who controlled the trade routes towards Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

, enabled them to gradually achieve the restoration of their autonomy. In 1486, Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

united the Saxon communities under the leadership of the elected mayor of Hermannstadt, who was thereafter known as the Count of the Saxons.

The '' Gesta Hungarorum''a book of debated reliabilitystated that Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easte ...

(or Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym '' Vlachs'') are a Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Romanian culture and ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they live primarily in Romania and Moldova. The 2011 Romania ...

) had already been present in Transylvania in the late 9th century. The earliest contemporaneous records evidence that Romanian communities existed in southern Transylvania in the first decade of the 13th century. In contrast with the Roman Catholic Hungarians, Székelys and Saxons, the Romanians adhered to the Orthodox Church. Their administrative units were known as lands or districts. The Romanian district A Romanian district ( la, districtus Valachorum) was an autonomous administrative unit of the Vlachs (or Romanians) in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary.

Origins

According to scholars who say that the Romanians (or Vlachs) descended from the ...

s were initially located in royal estates, but most of them were given away to noblemen or prelates by the end of the Middle Ages, or the local chiefs (or ''knezes'') achieved the acknowledgement of their ownership from the kings.

Development

General assemblies

General assemblies of the noblemen from one or more counties developed into important forums of the administration of justice in the entire Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century.

General assemblies of the noblemen from one or more counties developed into important forums of the administration of justice in the entire Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century. Noblemen

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

formed the highest level of the society in the Transylvanian counties. The wealthiest nobles owned dozens of villages, but most noble families had only one or two villages, or only a part of a village. They had specific privileges, such as tax exemption (from 1324), and the right to administer justice in their estates (from 1342).

Székely chiefs could only seize private landed property in the counties, outside Székely Land

The Székely Land or Szeklerland ( hu, Székelyföld, ; ro, Ținutul Secuiesc and sometimes ; german: Szeklerland; la, Terra Siculorum) is a historic and ethnographic area in Romania, inhabited mainly by Székelys, a subgroup of Hungarians. I ...

. The wealthiest Saxons also attempted to acquire landed property in the counties, outside the jurisdiction of the Saxon communities. Being obliged to render services (primarily of military nature) for the lands that they possessed, the Romanian leaders' position was similar to the status of the " nobles of the Church" and other groups of conditional nobles. Consequently, they were not regarded real nobles, but the monarch could award them with nobility. The ennobled Romanians adopted their Hungarian peers' way of life, but dozens of Romanian noble families remained Orthodox for centuries.

In comparison with Hungary proper, the autonomy of the Transylvanian counties was limited, because the voivodes restricted the development of their self-governing bodies. The general assemblies of the Transylvanian counties disappeared in the middle of the 14th century. Instead, the voivodes or their deputies held general assemblies for all noblemen from all the counties of the province. The first recorded general meeting of the "nobles of the realm of Transylvania" was held in Keresztes at Torda (now Cristiş in Romania) on 8 June 1288. The assembly authorized the vice-voivode, Ladislaus Borsa, to assist the representative of Peter Monoszló, Bishop of Transylvania

:''There is also a Romanian Orthodox Archbishop of Alba Iulia and a Greek Catholic Archdiocese of Făgăraş and Alba Iulia.''

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia ( hu, Gyulafehérvári Római Katolikus Érsekség) is a Latin Church Ca ...

, in taking possession of three villages of a noble family to secure the payment of a fine. The administration of justice remained the principal task of such meetings, but the noblemen who attended the assemblies also regularly discussed other subjects, including the collection of the tithe or custom duties. Initially, all noblemen were entitled to be present, but from the 15th century, the counties sent delegates to the assemblies.

The general assembly of the Székelys could be convoked by the Count of the Székelys, or by the captain of Udvarhelyszék. The internal issues of the Saxons communities were initially regulated by the assemblies of the Saxon seats and districts. From 1486, the Count of the Saxons presided over the annual general assemblies of the entire community, which consisted of the highest-ranking officials of the seats and districts and elected delegates.

The monarchs or on their behalf the voivodes could also convoke the representatives of all privileged groups of Transylvania to meet at a joint assembly. Andrew III of Hungary

Andrew III the Venetian ( hu, III. Velencei András, hr, Andrija III. Mlečanin, sk, Ondrej III.; 1265 – 14 January 1301) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1290 and 1301. His father, Stephen the Posthumous, was the posthumous son of ...

was the first king to hold such an assembly for the representatives of the Transylvanian noblemen, Saxons, Székelys and Romanians in early 1291. According to Andrew's charter mentioning the meeting, the king ordered the return of two domains to Ugrin Csák

Ugrin (III) from the kindred Csák ( hu, Csák nembeli (III.) Ugrin, hr, Ugrin Čak, sr, Угрин Чак; died in 1311) was a prominent Hungarian baron and oligarch in the early 14th century. He was born into an ancient Hungarian clan. He ac ...

after those who attended the general assembly testified that he had been their lawful owner.

Union of the Three Nations

Transylvania was regularly raided by Ottoman armies from the 1420s, forcing the monarchs and the local authorities to strengthen the defense of the province. At the initiative ofSigismund of Luxembourg

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 – 9 December 1437) was a monarch as King of Hungary and Croatia (''jure uxoris'') from 1387, King of Germany from 1410, King of Bohemia from 1419, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in ...

, King of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 175 ...

, the general assembly of the Transylvanian noblemen ordered in 1419 that one third of the noblemen and one tenth of the peasants were to take up arms in case of an Ottoman invasion against the Székely and Saxon territories.

New taxes were introduced and the old taxes were increased to cover the costs of defense, which outraged the peasantry. After George Lépes, Bishop of Transylvania

:''There is also a Romanian Orthodox Archbishop of Alba Iulia and a Greek Catholic Archdiocese of Făgăraş and Alba Iulia.''

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia ( hu, Gyulafehérvári Római Katolikus Érsekség) is a Latin Church Ca ...

, demanded the payment of the tithe that he had failed to collect in the previous years, thousands of Hungarian and Romanian commoners and lesser noblemen took up arms against him in early 1437. They routed the army of the voivode, Ladislaus Csáki, in July. Without seeking royal authorization, the vice-voivode convoked the noblemen and the leaders of the Székelys and Saxons to hold a joint assembly at Kápolna (now Căpâlna in Romania). At the meeting, the representatives of the noblemen, Székelys and Saxons concluded a "brotherly union" on 16 September, pledging to provide assistance to each other against their internal and external enemies.

The agreement of the three privileged groups gave rise to the idea of the " Union of the Three Nations of Transylvania", which replaced the previous concept about the three Transylvanian regions (that is, the counties, and the Székely and Saxon seats). The noblemen (including the Székely, Saxon, Romanian nobles who held landed property in the counties) made up the Hungarian nation, but the Hungarian peasants were excluded from this group. The Székelys formed a separate nation, although they spoke Hungarian. The Saxons who lived in the privileged districts were the members of the Saxon nation, but the Saxon population of the counties was not included.

The "brotherly union" was first confirmed on 2 February 1438, after the fall of the peasant revolt. The representatives of the Three Nations again confirmed their alliance in 1459, expanding it against all who threatened their liberties. The regular meetings of the delegates of the Three Nations developed into "Transylvania's foremost representative" assemblies, providing basis for the Transylvanian Diet.

The legislative function of the assemblies strengthened in the second half of the 15th century. In 1463, the representatives of the "Three Nations" ordered that the poorest noblemen and the Hungarian peasants should stay behind to defend the province although King Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

had ordered a general mobilisation against the Ottomans. In 1494, the general assembly forbade the collection of the extraordinary tax that Vladislaus II of Hungary had introduced, forcing the monarch to personally come to Transylvania and preside over the next general assembly. The role of the separate general assemblies of the Székelys also strengthened. A general assembly which was held without the consent of the Count of the Székelys in 1505 established a supreme court for Székely Land

The Székely Land or Szeklerland ( hu, Székelyföld, ; ro, Ținutul Secuiesc and sometimes ; german: Szeklerland; la, Terra Siculorum) is a historic and ethnographic area in Romania, inhabited mainly by Székelys, a subgroup of Hungarians. I ...

.

Disintegration of Hungary

Transylvania was mentioned as a ''regnum'' (or realm) in royal charters already in the second half of the 13th century. When writing of the ''regnum Transylvanum'', the royal charters initially referred to the Transylvanian noblemen who formed a closed community "bound together by certain reciprocal rights and duties". The Székely and Saxon communities were included in the concept only after the confirmation of the Union of the Three Nations in 1459. The '' Tripartitum''the compendium of the customary law of Hungary, completed in 1514explicitly acknowledged that Transylvania was a separate realm, with her own peculiar customs, but it also emphasized that Transylvania was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The laws of the Kingdom of Hungary were to be applied in Transylvania and the decisions of the royal courts of justice were also to be obeyed in the province.

The

Transylvania was mentioned as a ''regnum'' (or realm) in royal charters already in the second half of the 13th century. When writing of the ''regnum Transylvanum'', the royal charters initially referred to the Transylvanian noblemen who formed a closed community "bound together by certain reciprocal rights and duties". The Székely and Saxon communities were included in the concept only after the confirmation of the Union of the Three Nations in 1459. The '' Tripartitum''the compendium of the customary law of Hungary, completed in 1514explicitly acknowledged that Transylvania was a separate realm, with her own peculiar customs, but it also emphasized that Transylvania was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The laws of the Kingdom of Hungary were to be applied in Transylvania and the decisions of the royal courts of justice were also to be obeyed in the province.

The Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

, Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

, annihilated the royal army in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

on 29 August 1529. Louis II of Hungary died and two candidates laid claim to the vacant throne. The majority of the noblemen elected the voivode of Transylvania, John Zápolya

John Zápolya or Szapolyai ( hu, Szapolyai/ Zápolya János, hr, Ivan Zapolja, ro, Ioan Zápolya, sk, Ján Zápoľský; 1490/91 – 22 July 1540), was King of Hungary (as John I) from 1526 to 1540. His rule was disputed by Archduke Fer ...

, king, but the wealthiest magnates offered the throne to Louis II's brother-in-law, Ferdinand of Habsburg, Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, thos ...

. During the ensuing civil war, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary was actually divided into two parts, with John Zápolya controlling the eastern regions, including Transylvania. Taking advantage of the turmoil which followed Zápolya's death in 1540, Suleiman conquered the central regions of the kingdom in late summer 1541. However, he allowed Zápolya's widow, Isabella Jagiellon

Isabella Jagiellon ( hu, Izabella királyné, links=no; pl, Izabela Jagiellonka, links=no; 18 January 1519 – 15 September 1559) was the Queen consort of Hungary. She was the oldest child of Polish King Sigismund I the Old, the Grand Duke of Lit ...

, to continue to rule the lands to the east of the Tisza on behalf of her infant son, John Sigismund Zápolya

John Sigismund Zápolya or Szapolyai ( hu, Szapolyai János Zsigmond; 7 July 1540 – 14 March 1571) was King of Hungary as John II from 1540 to 1551 and from 1556 to 1570, and the first Prince of Transylvania, from 1570 to his death. He was ...

, who had already been elected king at the initiative of his father's staunch supporter, George Martinuzzi

George Martinuzzi, O.S.P. (born Juraj Utješenović, also known as György Martinuzzi, Brother György, Georg Utiessenovicz-Martinuzzi or György Fráter, hu, Fráter György; 1482 – 16 December 1551), was a Croatian nobleman, Pauline m ...

.

Martinuzzi held an assembly for the representatives of the privileged groups of John Sigismund's realm in Debrecen

Debrecen ( , is Hungary's second-largest city, after Budapest, the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar County. A city with county rights, it was the largest Hungarian city in the 18th century and ...

on 18 October 1541. This was the first Diet where both the Three Nations of Transylvania and the counties of Partium (the region between the Tisza and Transylvania) were represented. The delegates swore fealty to the Zápolyas and acknowledged the sultan's suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

. The following similar Diet was held only in 1544, but thereafter the delegates from the Partium were always invited to attend the Diet. Consequently, the Diet of John Sigismund's realm became a legal successor of the medieval Diet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale ( hu, Országgyűlés) became the supreme legislative institution in the medieval kingdom of Hungary from the 1290s, and in its successor states, Royal Hungary and ...

. Laws could only be enacted and taxes could only be collected with the consent of the Diet, but most Diets were dominated by the monarch's partisans, which secured the imposition of royal will.

Age of elected princes

History

John Sigismund only renounced the title of king of Hungary in the Treaty of Speyer in 1570. Thereafter he was styledprince of Transylvania

The Prince of Transylvania ( hu, erdélyi fejedelem, german: Fürst von Siebenbürgen, la, princeps Transsylvaniae, ro, principele TransilvanieiFallenbüchl 1988, p. 77.) was the head of state of the Principality of Transylvania from the last d ...

, but his successors' right to use the new title was acknowledged by the Habsburg rulers of Royal Hungary

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ...

only in 1595, during the reign of Sigismund Báthory

Sigismund Báthory ( hu, Báthory Zsigmond; 1573 – 27 March 1613) was Prince of Transylvania several times between 1586 and 1602, and Duke of Racibórz and Opole in Silesia in 1598. His father, Christopher Báthory, ruled Transylvania as vo ...

. In that year, Báthory joined the anti-Ottoman Holy League of Pope Clement VIII.

The Diets

Composition

The Diet wasunicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

, with both appointed and elected members. Most Diets were attended by 130-150 persons. The noblemen (the "Hungarian nation") dominated the Diets, but the Székelys' military power and the Saxons' wealth secured the effective protection of their interests. The majority of the members of the Diets adhered to the Reformed Church

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

in the 17th century. The Saxons represented the Evangelical Church

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "born again", in which an individual experi ...

, but the Catholic and Unitarian denominations were in practice reduced to background.

Royal counselors, judges of the royal court of justice and other high-ranking royal officials were ex officio member

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

s of the Diet. Available data show that the bishops of the Reformed and Evangelical Churches also had seats at the Diets, according to historian Zsolt Trócsányi. The bishops of the Orthodox Romanians were certainly notified when the Diet was announced, but their regular presence is not documented. The presence of Catholic prelates is uncertain. János Bethlen recorded that the vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

of the Catholic Diocese of Transylvania was deliberately ignored in 1666, because the Catholic priests had denied to pay taxes.

The princes were entitled to invite individuals to attend the Diet. The number of these "regalists" was not regulated, but more than twenty noblemen received a personal invitation from the monarch before each Diet. The number of regalists increased: more than 80 noblemen were personally invited to the Diet in 1686. Most regalists were members of the wealthiest noble families. Székely leaders were also personally invited, although the Székely community opposed this practice. According to János Bethlen's notes, the widows of former regalists were customarily also requested to send representatives to the Diets.

The counties, Saxon and Székely seats and about twenty towns had the right to send delegates to the Diets. The number of delegates depended of the importance of the issues to be discussed. According to a decree of the Diet which assembled in April 1571, each county and Székely seat had to send ten representatives to the following Diet where the successor of John Sigismund was to be elected. However, this was an extremely high number; sporadic data show that each autonomous community dispatched two to eight delegates to most Diets.

The speaker of the Diet (or ''praeses'') held the third most important office in the principality. The speakers and their deputies were almost always appointed by the monarchs. Gábor Haller was the only speaker who was elected by the delegates in the Diets of 1660 and 1661. In most documented cases, the heads of the royal court of justice presided over the Diets. Most speakers were also royal counselors and heads of a county or a Székely seat.

Convocation

The monarchs had the right to summon the Diets. If the prince was absent and during interregnums, the prince's representative (the voivode or governor) convened the assembly. The Diet could also pass a decree ordering the summon of the following Diet, but this happened only exceptionally. The prince or his deputy convened the Diet in a letter, which was in most cases also signed by the chancellor. The letter was posted 2–4 weeks before the opening of the Diet. The appearance at the Diet was obligatory: those who failed were fined 100-200 florins. More than 320 Diets were held from 1571 to 1690, but their annual number fluctuated from year to year. The delegates assembled more frequently during the periods of turmoil. For instance, the Diet was convoked more than fifty times between 1594 and 1606, and more than fifty-five times between 1657 and 1667. According to customary law, the princes were required to hold two Diets in each year. The first Diet of the year was convoked aroundSaint George's Day

Saint George's Day is the feast day of Saint George, celebrated by Christian churches, countries, and cities of which he is the patron saint, including Bulgaria, England, Georgia, Portugal, Romania, Cáceres, Alcoy, Aragon and Catalonia.

Sai ...

(24 April). The second or "short Diet" was customarily held around the feast of Saint Michael

Michael (; he, מִיכָאֵל, lit=Who is like El od, translit=Mīḵāʾēl; el, Μιχαήλ, translit=Mikhaḗl; la, Michahel; ar, ميخائيل ، مِيكَالَ ، ميكائيل, translit=Mīkāʾīl, Mīkāl, Mīkhāʾīl), also ...

(29 September), but Gabriel Bethlen

Gabriel Bethlen ( hu, Bethlen Gábor; 15 November 1580 – 15 November 1629) was Prince of Transylvania from 1613 to 1629 and Duke of Opole from 1622 to 1625. He was also King-elect of Hungary from 1620 to 1621, but he never took control of th ...

persuaded the Estates to cancel it in 1622.

Most Diets assembled in Gyulafehérvár, especially in the 1590s and between 1613 and 1658. Although the town had customarily been the Transylvanian rulers' seat, the delegates preferred Torda, Kolozsvár and Nagyenyed (now Cluj-Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = Counties of Romania, County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Subdivisions of Romania, Status

, subdivision_name2 ...

and Aiud in Romania), which were located in the central region of the principality. Frequent invasions forced Michael I Apafi to convoke the Diets to the fortresses of Fogaras and Radnót (now Făgăraș and Iernut in Romania) in the late 1680s.

The delegates received detailed instructions at their appointment. Most instructions concerned local issues (such as trade privileges and conflicts between burghers and noblemen), enabling the delegates to freely discuss general topics. However, they could occasionally refer to the lack of instructions if they did not want to discuss certain subjects. For instance, when Michael I Apafi tried to persuade the Diet to pass decrees concerning issues which had not been mentioned in his letter of invitation, the delegates resisted, saying that their instructions did not cover these topics.

Procedure

If the Diet was held in a town other than the prince's seat, the prince came to the town days before the opening of the Diet. The delegates of each Nation or denomination could hold separate meetings before the opening to draft their own proposals on specific issues relating to their community. On the first day of the Diet, the delegates attended a morning worship in a church which was in most cases also the venue of the sessions of the Diets. The sessions could also be held in military camps, or even in a barn in case of emergency. After the morning worship, the delegates sent envoys to the monarch to inform him that they had assembled for the Diet. The princes rarely attended the sessions, but they were represented either by their appointed heirs or lieutenants. The speaker of the Diet made sure that all who had been invited were present. For this purposes, two delegates were required to read out the names of all delegates at the opening of the Diet. The speaker was also responsible for keeping order during the debates. The sessions of the Diets were public, but the Diet could decide to hold a close meeting. In most documented cases, the "propositions" of the monarch about the topics to be discussed were read out soon after the opening of the Diet. Next, the delegates compiled a memorandum to air the grievances of each Nation,The Nations could, for instance, make complaints about arbitrary actions of the monarchs or their officials. For example, afterGabriel Báthory

Gabriel Báthory ( hu, Báthory Gábor; 15 August 1589 – 27 October 1613) was Prince of Transylvania from 1608 to 1613. Born to the Roman Catholic branch of the Báthory family, he was closely related to four rulers of the Principality of ...

who had occupied Hermannstadt was murdered, the Saxons demanded the restoration of the town to their community from the new prince, Gabriel Bethlen

Gabriel Bethlen ( hu, Bethlen Gábor; 15 November 1580 – 15 November 1629) was Prince of Transylvania from 1613 to 1629 and Duke of Opole from 1622 to 1625. He was also King-elect of Hungary from 1620 to 1621, but he never took control of th ...

, in October 1613. The Nations could also demand tax relief or similar concessions. For example, the Székelys requested the prince to exempt them from public labor in spring 1628. ''(Péter (1994), pp. 313, 316; Trócsányi (1976), pp. 83–87, 90)'' asking the prince to remedy their problems. The prince was required to respond each point of the memorandum. If the monarch's answer did not satisfy the delegates, the prince and the Diet started to exchange letters about the debated issues. The correspondence lasted until they reached a consensus, or the Diet acknowledged that the prince was unwilling to accept their proposal. The delegates started to discuss the royal propositions only after the debate about their memorandum was finished.

Hungarian was the language of the discussions. Each delegate could take the floor, but they were required to stay concise. After closing the debate, the speaker summarized its main points and ordered the delegates to take their votes on the issue under discussion. The decisions passed at the Diets were sanctioned by the monarch. The execution of the laws was also a royal prerogative.

Functions

The princes were elected at the Diets, according to the fundamental laws of the principality. The negotiations preceding a prince's election enabled the Three Nations to secure the issue of a specific charter in which the future monarch pledged to respect their liberties. However, few monarchs were actually freely elected. For instance, Gabriel Báthory seized the throne with the support of the irregular '' Hajdú'' troops in 1608; the delegates elected Gabriel Bethlen "freely in their fear" of Ottoman intervention in 1613, according to the contemporaneous Ferenc Nagy Szabó's sarcastic remark. The Diets performed legislative, administrative and judicial functions. The Diet could authorize the monarch or the royal council to perform its functions. For instance, Christopher Báthory was authorized to take actions against radical Protestants in 1578. Almost 5,000 decrees were passed in the 16th and 17th centuries. Their analysis evidence that the monarchs dominated the political life of the principality. The delegates almost always accepted the royal propositions concerning taxation and made only one attempt to regulate the spending of tax revenues in 1593. They also regularly authorized the monarch to mobilize the general levy. They enacted the state monopolies without significant resistance, although, during the reign of George I Rákóczi, only after lengthy negotiations with the prince. On the other hand, the Diets passed hundreds of decrees about issues of local interest, including the regulation of the quest for runaway serfs or of the boundaries of noble estates. The Diets also functioned as a high court of justice, especially in politically motivated cases. Gabriel Bethlen was found guilty ofhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

at the Diet in November 1612, but this decision was cancelled at the first Diet of his rule in October 1613. The Diet sentenced Kata Iffjú, the widow of János Imreffy

János Imreffy de Szerdahely (''Imreffi''; c. 1559-60 – 9 July 1611)Markó 2006, p. 108. was a Hungarian soldier and noble in the Principality of Transylvania, who served as Chancellor of Transylvania from Spring 1610 to his death on 9 ...

(who had been Gabriel Báthory's chancellor) to death for incest, fornication and witchcraft during the reign of Báthory's successor, Gabriel Bethlen in early 1614. The legal cases were heard at specific judicial sessions.

The Diets sometimes entered into direct correspondence with foreign powers, but the letters evidence that the support of the monarchs' specific diplomatic acts was the delegates' principal purpose. Correspondence between the Diet and pretenders or other internal opponents of the monarch is also documented, especially in the second half of the 17th century.

Notes

References

Sources

Primary sources

* ''Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517)'' (Edited and translated by János M. Bak, Péter Banyó and Martyn Rady with an introductory study by László Péter) (2005). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers. .Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Transylvanian Diet Principality of Transylvania (1570–1711) Defunct unicameral legislatures