Transylvania

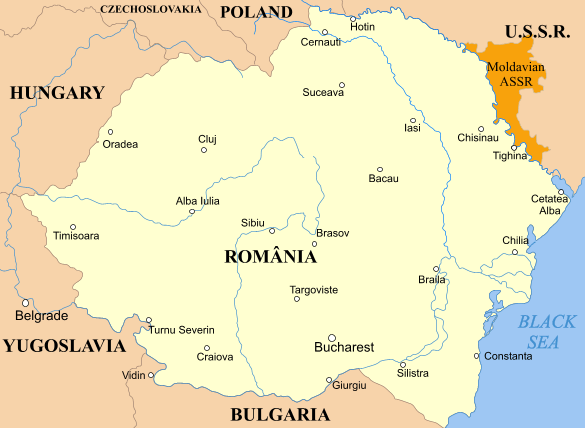

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

is a historical region in central and northwestern

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

. It was under the rule of the

Agathyrsi, part of the

Dacian Kingdom

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It t ...

(168 BC–106 AD),

Roman Dacia

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania a ...

(106–271), the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

, the

Hunnic Empire

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

(4th–5th centuries), the

Kingdom of the Gepids (5th–6th centuries), the

Avar Khaganate

The Pannonian Avars () were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of various origins. The peoples were also known as the Obri in chronicles of Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai ( el, Βαρχονίτες, Varchonítes), or Pseudo-Avars ...

(6th–9th centuries), the

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, and the 9th century

First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire ( cu, блъгарьско цѣсарьствиѥ, blagarysko tsesarystviye; bg, Първо българско царство) was a medieval Bulgar- Slavic and later Bulgarian state that existed in Southeastern Eur ...

. During the late 9th century,

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

was reached and conquered by the

Hungarian conquerors, and

Gyula's family from

seven chieftains of the Hungarians ruled

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

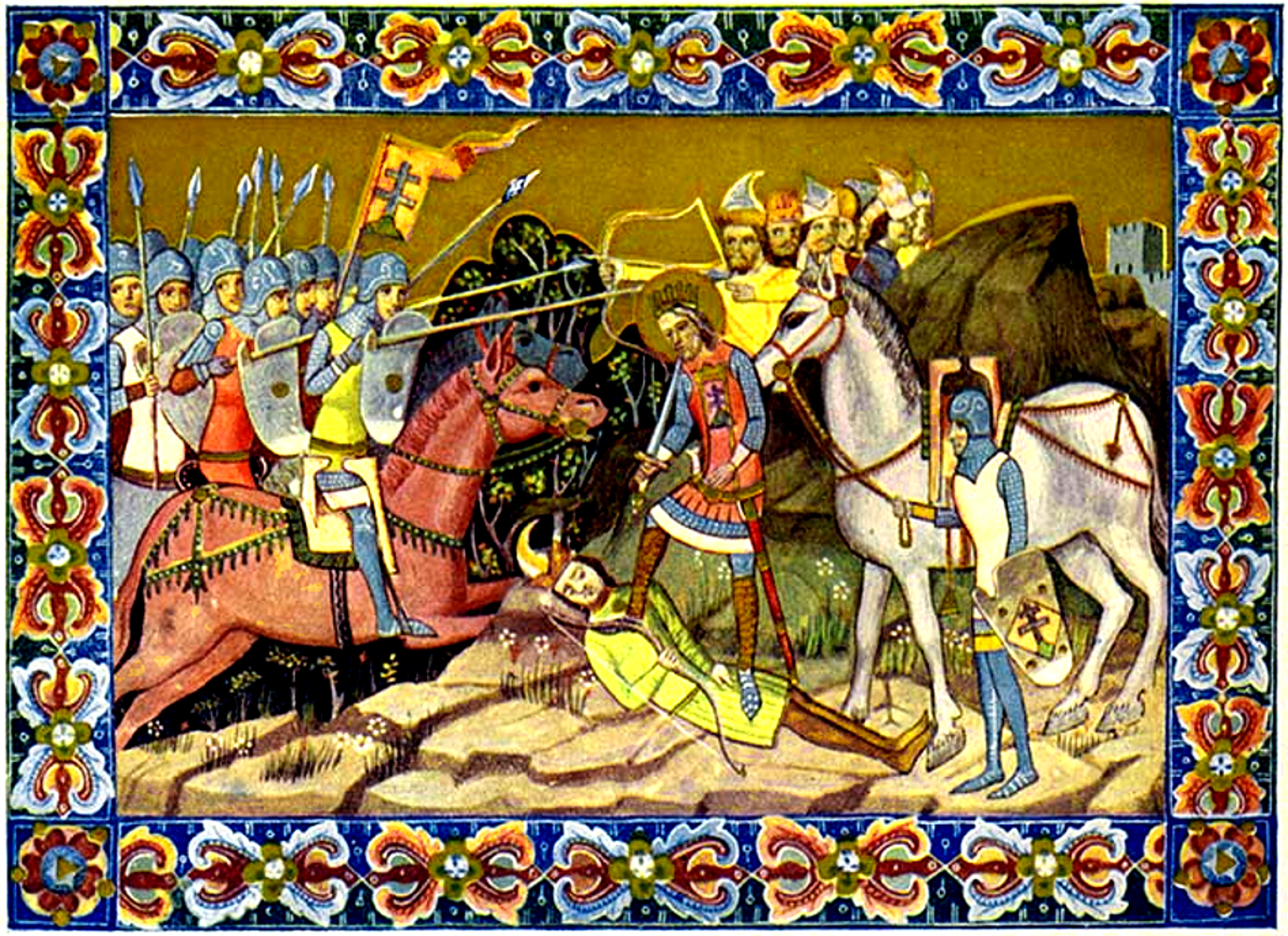

in the 10th century. King

Stephen I of Hungary

Stephen I, also known as King Saint Stephen ( hu, Szent István király ; la, Sanctus Stephanus; sk, Štefan I. or Štefan Veľký; 975 – 15 August 1038), was the last Grand Prince of the Hungarians between 997 and 1000 or 1001, and the ...

asserted his claim to rule all lands dominated by Hungarian lords, and he personally led his army against his maternal uncle

Gyula III

Gyula III, also Iula or Gyula the Younger, Geula or Gyla, was an early medieval ruler in Transylvania ( – 1003/1004). Around 1003, he and his family were attacked, dispossessed and captured by King Stephen I of Hungary (1000/1001-1038). The name ...

.

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

became part of the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

in 1002, and it belonged to the

Lands of the Hungarian Crown

The "Lands of the Hungarian Crown"Laszlo PéterHungary's Long Nineteenth Century: Constitutional and Democratic Traditions in a European Perspective BRILL, 2012, pp. 51–56 was the titular expression of Hungarian pretensions to the various territo ...

until 1920.

After the

Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526 it belonged to the

Eastern Hungarian Kingdom

The Eastern Hungarian Kingdom ( hu, keleti Magyar Királyság) is a modern term coined by some historians to designate the realm of John Zápolya and his son John Sigismund Zápolya, who contested the claims of the House of Habsburg to rule th ...

, from which the

Principality of Transylvania emerged in 1570 by the

Treaty of Speyer. During most of the 16th and 17th centuries, the principality was a

vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back t ...

of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

; however, the principality had dual

suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

ty (

Ottoman and

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

).

In 1690, the

Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

gained possession of

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

through the

Hungarian crown.

[Paul Lendvai, Ann Major]

''The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat''

C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, page 146; After the failure

Rákóczi's War of Independence

Rákóczi's War of Independence (1703–11) was the first significant attempt to topple the rule of the Habsburgs over Hungary. The war was conducted by a group of noblemen, wealthy and high-ranking progressives and was led by Francis II Rákó ...

in 1711 Habsburg control of

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

was consolidated, and Hungarian

Transylvanian princes were replaced with Habsburg imperial governors.

["Transylvania"]

(2009). ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved July 7, 2009["Diploma Leopoldinum"]

(2009). ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved July 7, 2009 During the

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 or fully Hungarian Civic Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 () was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Although t ...

, the Hungarian government proclaimed union with

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

in the

April Laws of 1848. After the failure of the revolution, the

March Constitution of Austria The March Constitution, Imposed March Constitution or Stadion Constitution (German: ' or ') was an "irrevocable" constitution of the Austrian Empire promulgated by Minister of the Interior Count Stadion between 4 March and 7 March 1849 until it was ...

decreed that the

Principality of Transylvania be a separate crown land entirely independent of

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

.

[Austrian Constitution of 4 March 1849](_blank)

(Section I, Art. I and Section IX., Art. LXXIV) After the

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hunga ...

, the separate status of

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

ceased, it was incorporated again into the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

(

Transleithania

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen ( hu, a Szent Korona Országai), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River) were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire exis ...

) as part of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. After

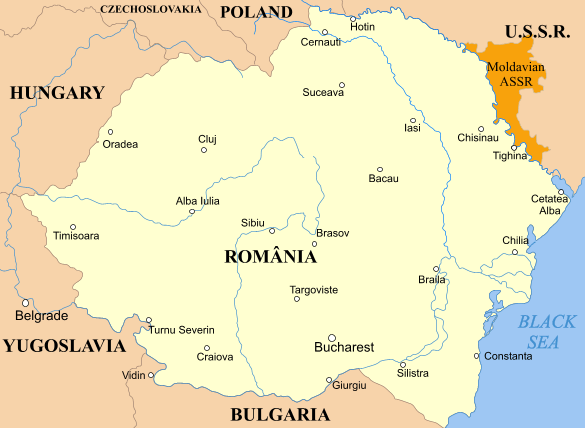

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

,

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

became part of

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

by the

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

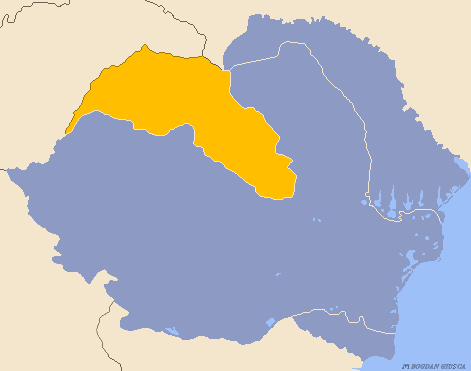

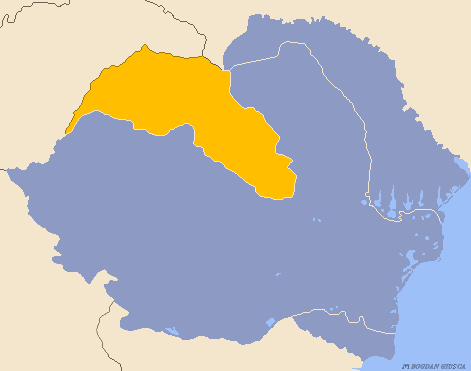

in 1920. In 1940,

Northern Transylvania

Northern Transylvania ( ro, Transilvania de Nord, hu, Észak-Erdély) was the region of the Kingdom of Romania that during World War II, as a consequence of the August 1940 territorial agreement known as the Second Vienna Award, became part of ...

reverted to

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

as a result of the

Second Vienna Award

The Second Vienna Award, also known as the Vienna Diktat, was the second of two territorial disputes that were arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On 30 August 1940, they assigned the territory of Northern Transylvania, including all o ...

, but it was reclaimed by

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

after the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Due to its varied history the population of Transylvania is ethnically, linguistically, culturally and religiously diverse. From 1437 to 1848 political power in Transylvania was shared among the mostly

Hungarian nobility

The Hungarian nobility consisted of a privileged group of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, in the Kingdom of Hungary. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as noblemen, but from the late 12th century only high ...

, German

burghers and the

seats

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but also headquarters in a wider sense.

Types of seat

The following are examples of different kinds of seat:

* Armchair, a chair eq ...

of the

Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

(a Hungarian ethnic group). The population consisted of

Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym '' Vlachs'') are a Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Romanian culture and ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they live primarily in Romania and Moldova. The 2011 Romania ...

,

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

(particularly Székelys) and

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. The majority of the present population is Romanian, but large minorities (mainly Hungarian and

Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

) preserve their traditions. However, as recently as the

communist era ethnic-minority relations remained an issue of international contention. This has abated (but not disappeared) since the

Revolution of 1989 restored democracy in Romania. Transylvania retains a significant

Hungarian-speaking minority, slightly less than half of which identify themselves as Székely.

Ethnic Germans in Transylvania (known as Saxons) comprise about one percent of the population; however, Austrian and German influences remain in the architecture and urban landscape of much of Transylvania.

The region's history may be traced through the religions of its inhabitants. For the first time in history, the

Diet of Torda in 1568 declared freedom of religion. There was no state religion, while in other parts of Europe and the world religious wars were fought. The Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, and Unitarian Churches and religions were declared to be fully equal, and the Romanian Orthodox religion was tolerated. Most Romanians in Transylvania belong to the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

faith, but from the 18th to the 20th centuries the

Romanian Greek-Catholic Church also had substantial influence. Hungarians primarily belong to the

Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

or

Reformed Churches; a smaller number are

Unitarians. Of the ethnic Germans in Transylvania, the Saxons have primarily been

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

since the

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

; however, the

Danube Swabians are Catholic. The

Baptist Union of Romania is the second-largest such body in Europe;

Seventh-day Adventists are established, and other

evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

churches have been a growing presence since 1989. No

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

communities remain from the era of the

Ottoman invasions. As elsewhere,

anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

20th century politics saw Transylvania's once sizable

Jewish population

As of 2020, the world's "core" Jewish population (those identifying as Jews above all else) was estimated at 15 million, 0.2% of the 8 billion worldwide population. This number rises to 18 million with the addition of the "connected" Jewish pop ...

greatly reduced by the

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

and emigration.

Name of Transylvania

The earliest known reference to Transylvania appears in a

Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

document of the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

in 1075 as ''"ultra silvam"'', in the

Gesta Hungarorum

''Gesta Hungarorum'', or ''The Deeds of the Hungarians'', is the earliest book about Hungarian history which has survived for posterity. Its genre is not chronicle, but ''gesta'', meaning "deeds" or "acts", which is a medieval entertaining li ...

as ''"terra ultrasilvana"'', meaning "land beyond the forest" (''"terra"'' means land, ''"ultra"'' means "beyond" or "on the far side of" and the accusative case of ''"silva"'', ''"silvam"'' means "woods, forest"). Transylvania, with an alternative Latin prepositional prefix, means "on the other side of the woods". The Hungarian form ''Erdély'' was first mentioned in the

Gesta Hungarorum

''Gesta Hungarorum'', or ''The Deeds of the Hungarians'', is the earliest book about Hungarian history which has survived for posterity. Its genre is not chronicle, but ''gesta'', meaning "deeds" or "acts", which is a medieval entertaining li ...

as ''"Erdeuelu".'' Hungarian historians claim that the Medieval Latin form ''"Ultrasylvania",'' later Transylvania, was a direct translation from the Hungarian form ''"Erdőelve"'' (''"erdő"'' means "forest" and ''"elve"'' means "beyond" in old Hungarian).

[Engel, Pál (2001). ''Realm of St. Stephen: History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526 (International Library of Historical Studies)'', page 24, London: I.B. Taurus. ] That also was used as an alternative name in German "''Überwald"'' (''"über"'' means "beyond" and ''"wald"'' means forest) in the 13th–14th centuries. The earliest known written occurrence of the Romanian name ''Ardeal'' appeared in a document in 1432 as ''"Ardeliu"''. The Romanian ''Ardeal'' is derived from the Hungarian ''Erdély''.

''Erdelj'' in Serbian and Croatian, ''Erdel'' in Turkish were borrowed from this form as well.

According to the Romanian linguist

Nicolae Drăganu

Nicolae Drăganu (18 February 1884 – 18 December 1939) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian linguist, philologist, and literary historian.

Biography

Born in Zagra, Bistrița-Năsăud County, into a Greek-Catholic family, he attended primary ...

, the Hungarian name of Transylvania evolved over time from ''Erdőelü'', ''Erdőelv'', ''Erdőel'', ''Erdeel'' in chronicles and written charters from 1200 up to late 1300. In written sources from 1390, we can find also the form ''Erdel'', which can be read also as ''Erdély''. There is evidence for that in the written Wallachian Chancellery Charters expressed in Slavonic where the word appears as ''Erûdelû'' (1432), ''Ierûdel'', ''Ardelîu'' (1432), ''ardelski'' (1460, 1472, 1478–1479, 1480, 1498, 1507–1508, 1508), ''erdelska'', ''ardelska'' (1498). With the first texts written in Romanian (1513) the name ''Ardeal'' appears to be written.

Ancient history

Dacian states

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

gives an account of the

Agathyrsi, who lived in Transylvania during the fifth century BCE. He described them as a luxurious people who enjoyed wearing gold ornaments. Herodotus also claimed that the Agathyrsi held their wives in common, so all men would be brothers.

A kingdom of

Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

existed at least as early as the early second century BCE under King

Oroles

Oroles was a Dacian king during the first half of the 2nd century BC.

He successfully opposed the Bastarnae, blocking their invasion into Transylvania.

The Roman historian Trogus Pompeius wrote about king Oroles punishing his soldiers into sleepi ...

. Under

Burebista

Burebista ( grc, Βυρεβίστας, Βοιρεβίστας) was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61BC to 45/44BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area loca ...

, the foremost king of Dacia and a contemporary of

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, the kingdom reached its maximum extent. The area now constituting Transylvania was the political center of Dacia.

The Dacians are often mentioned by

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, according to whom they were compelled to recognize

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

supremacy. However, they were not subdued and in later times crossed the frozen

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

during winter and ravaging Roman cities in the recently acquired

Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

.

The Dacians built several important

fortified cities, among them

Sarmizegetusa (near the present

Hunedoara

Hunedoara (; german: Eisenmarkt; hu, Vajdahunyad ) is a city in Hunedoara County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in southwestern Transylvania near the Poiana Ruscă Mountains, and administers five villages: Boș (''Bós''), Groș (''Grós ...

). They were divided into

two classes: the aristocracy (''tarabostes'') and the common people (''comati'').

Roman-Dacian Wars

The

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

expansion in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

brought the Dacians into open conflict with Rome. During the reign of

Decebalus

Decebalus (), sometimes referred to as Diurpaneus, was the last Dacian king. He is famous for fighting three wars, with varying success, against the Roman Empire under two emperors. After raiding south across the Danube, he defeated a Roman invas ...

, the Dacians were engaged in

several wars with the Romans from 85 to 89 CE. After two reverses the Romans gained an advantage but were obliged to make peace due to the defeat of

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

by the

Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

O ...

. Domitian agreed to pay large sums (eight million

sesterces

The ''sestertius'' (plural ''sestertii''), or sesterce (plural sesterces), was an Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Roman currency, coin. During the Roman Republic it was a small, silver coin issued only on rare occasions. During the Roman Empire it w ...

) in annual tribute to the Dacians for maintaining peace.

In 101 the emperor

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

began a

military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from the ...

against the

Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often consi ...

, which included a

siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

of Sarmizegetusa Regia and the occupation of part of the country. The Romans prevailed but Decebalus was left as a

client king

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

under a Roman

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

. Three years later, the Dacians rebelled and destroyed the Roman troops in Dacia. As a result, Trajan quickly began a new campaign against them (105–106). The

battle for Sarmizegetusa Regia took place in the early summer of 106 with the participation of the

II Adiutrix and

IV Flavia Felix legions and a detachment (''vexillatio'') from the

Legio VI Ferrata

Legio VI Ferrata ("Sixth Ironclad Legion") was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. In 30 BC it became part of the emperor Augustus's standing army. It continued in existence into the 4th century. A ''Legio VI'' fought in the Roman Republican ...

. The Dacians repelled the first attack, but the water pipes from the Dacian capital were destroyed. The city was set on fire, the pillars of the sacred sanctuaries were cut down and the fortification system was destroyed; however, the war continued. Through the treason of Bacilis (a confidant of the Dacian king), the Romans found

Decebalus' treasure in the

Strei River (estimated by

Jerome Carcopino as 165,500 kg of gold and 331,000 kg of silver). The last battle with the army of the Dacian king took place at

Porolissum

Porolissum was an ancient Roman city in Dacia. Established as a military camp in 106 during Trajan's Dacian Wars, the city quickly grew through trade with the native Dacians and became the capital of the province Dacia Porolissensis in 124. The si ...

(Moigrad).

Dacian culture encouraged its soldiers to not fear death, and it was said that they left for war merrier than for any other journey. In his retreat to the mountains, Decebalus was followed by

Roman cavalry led by

Tiberius Claudius Maximus. The Dacian religion of

Zalmoxis

Zalmoxis ( grc-gre, Ζάλμοξις) also known as Salmoxis (Σάλμοξις), Zalmoxes (Ζάλμοξες), Zamolxis (Ζάμολξις), Samolxis (Σάμολξις), Zamolxes (Ζάμολξες), or Zamolxe (Ζάμολξε) is a divinity of the ...

permitted suicide as a last resort by those in pain and misery, and the Dacians who heard Decebalus' last speech dispersed and committed suicide. Only the king tried to retreat from the Romans, hoping that he could find in the mountains and forests the means to resume battle, but the Roman cavalry followed him closely. After they almost caught him, Decebalus committed suicide by slashing his throat with his sword (

falx).

The history of the Dacian Wars was written by

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, and they are also depicted on

Trajan's Column

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Ap ...

in

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

Following the war, several parts of Dacia including Transylvania were organized into the Roman province of

Dacia Traiana

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (today ...

.

Roman Dacia

The Romans brought most vestiges of the

Roman culture into Dacia Traiana.

They sought to utilize the gold mines in the province and built access roads and forts (such as

Abrud

Abrud ( la, Abruttus;Ștefan Pascu: A History of Transylvania, Dorset Press, 1990, , hu, Abrudbánya; german: Großschlatten) is a town in the north-western part of Alba County, Transylvania, Romania, located on the river Abrud. It administer ...

) to protect them. The region developed a strong infrastructure and an economy based on agriculture, cattle farming and mining. Colonists from

Thracia

Thracia or Thrace ( ''Thrakē'') is the ancient name given to the southeastern Balkan region, the land inhabited by the Thracians. Thrace was ruled by the Odrysian kingdom during the Classical and Hellenistic eras, and briefly by the Greek D ...

,

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

,

Macedonia,

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

,

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and other Roman provinces were brought in to settle the land, developing cities like Apulum (now

Alba Iulia

Alba Iulia (; german: Karlsburg or ''Carlsburg'', formerly ''Weißenburg''; hu, Gyulafehérvár; la, Apulum) is a city that serves as the seat of Alba County in the west-central part of Romania. Located on the Mureș River in the historica ...

) and Napoca (now

Cluj Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Status

, subdivision_name2 = County seat

, settlement_type = City

, le ...

) into and

colonias.

During the third century, increasing pressure from the

Free Dacians

The so-called Free Dacians ( ro, Daci liberi) is the name given by some modern historians to those Dacians who putatively remained outside, or emigrated from, the Roman Empire after the emperor Trajan's Dacian Wars (AD 101-6). Dio Cassius named t ...

and

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

forced the Romans to abandon Dacia Traiana.

According to historian

Eutropius in Liber IX of his ''Breviarum,'' in 271, Roman citizens from Dacia Traiana were resettled by the Roman emperor

Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited ...

across the Danube in the newly established

Dacia Aureliana

Dacia Aureliana was a province in the eastern half of the Roman Empire established by Roman Emperor Aurelian in the territory of former Moesia Superior after his evacuation of Dacia Traiana beyond the Danube in 271. Between 271/275 and 285, ...

, inside former

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

Superior:

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages: the great migrations

Goths

Before their withdrawal the Romans negotiated an agreement with the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

in which Dacia remained Roman territory, and a few Roman outposts remained north of the Danube. The

Thervingi

The Thervingi, Tervingi, or Teruingi (sometimes pluralised Tervings or Thervings) were a Gothic people of the plains north of the Lower Danube and west of the Dniester River in the 3rd and the 4th centuries.

They had close contacts with the G ...

, a

Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

ic tribe, settled in the southern part of Transylvania, and the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

lived on the

Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, formed by the Caspian steppe and the Pontic steppe, is the steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Pontus Euxinus of antiquity) to the northern area around the Caspian Sea. It extend ...

.

About 340,

Ulfilas

Ulfilas (–383), also spelled Ulphilas and Orphila, all Latinized forms of the unattested Gothic form *𐍅𐌿𐌻𐍆𐌹𐌻𐌰 Wulfila, literally "Little Wolf", was a Goth of Cappadocian Greek descent who served as a bishop and missio ...

brought

Acacian Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

to the Goths in Guthiuda, and the Visigoths (and other Germanic tribes) became Arians.

The Gothic presence in the area of Transylvania starts in the second half of the 4th century and lasted for a few decades, at least until the Hunic invasion

The Goths were able to defend their territory for about a century against the

Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

and

Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

;

however, the Visigoths were unable to preserve the region's Roman infrastructure. Transylvania's gold mines were unused during the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

.

Huns

By 376 a new wave of migratory people, the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, led by

Uldin

Uldin, also spelled Huldin (died before 412) is the first ruler of the Huns whose historicity is undisputed.

Etymology

The name is recorded as ''Ουλδης'' (Ouldes) by Sozomen, ''Uldin'' by Orosius, and ''Huldin'' by Marcellinus Comes. On th ...

defeated and expelled the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

, setting up their own headquarters in what was

Dacia Inferior

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (today ...

. Hoping to find refuge from the Huns,

Fritigern (a Visigothic leader) appealed to the Roman emperor

Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

in 376 to be allowed to settle with his people on the south bank of the Danube. However, a famine broke out and Rome was unable to supply them with food or land. As a result, the Goths

rebelled against the Romans for several years. The Huns fought the

Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, and

Quadi

The Quadi were a Germanic

*

*

*

people who lived approximately in the area of modern Moravia in the time of the Roman Empire. The only surviving contemporary reports about the Germanic tribe are those of the Romans, whose empire had its bord ...

, forcing them toward the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. Pannonia became the centre during the peak of

Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and E ...

's reign (435–453).

Dating from 425 to 455, the

Transylvanian traces of the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

lie in the lowlands of the

Mureș valley. The most important testimonies of the

Hun

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

rule are the two separate sets of coins discovered at

Sebeș

Sebeș (; German: ''Mühlbach''; Hungarian: ''Szászsebes''; Transylvanian Saxon dialect: ''Melnbach'') is a city in Alba County, central Romania, southern Transylvania.

Geography

The city lies in the Mureș River valley and straddles the ri ...

. Between the 420s and 455,

Hun

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

princes and lords established summer residences in

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

. The newest discoveries strengthens the theory that there was a more serious

Hun

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

military presence in

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

.

Spread of Christianity

Sparse archeological findings from the 4th century (

Biertan Donarium

The Biertan Donarium is a fourth-century Christian votive object found near the town of Biertan, in Transylvania, Romania. Made out of bronze in the shape of a Labarum, it has the Latin text EGO ZENO VOTUM POSVI, which can be approximatively ...

, a clay pot with Christain symbols from

Moigrad, and another clay pot with

Chi Rho

The Chi Rho (☧, English pronunciation ; also known as ''chrismon'') is one of the earliest forms of Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ( Christos) in such a way that ...

monogram at the bottom from

Ulpia Traiana for example) point at minor Christian communities isolated from the main group.

The

Biertan Donarium

The Biertan Donarium is a fourth-century Christian votive object found near the town of Biertan, in Transylvania, Romania. Made out of bronze in the shape of a Labarum, it has the Latin text EGO ZENO VOTUM POSVI, which can be approximatively ...

was found in 1775. There are two theories on the origins of this artifact. According to the supporters of the Daco-Romanian continuity theory this donarium was made by the survivor Latin-speaking Christian population population of

Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It ...

following the

Aurelian Retreat

Roman Dacia ( ; also known as Dacia Traiana, ; or Dacia Felix, 'Fertile/Happy Dacia') was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat (tod ...

. Those historians who are sceptic about this object point to the dubious circumstances of this finding. They emphasize that there were no Roman settlements or Christian churches near to

Biertan. According to them this object was made in

Aquileia

Aquileia / / / / ;Bilingual name of ''Aquileja – Oglej'' in: vec, Aquiłeja / ; Slovenian: ''Oglej''), group=pron is an ancient Roman city in Italy, at the head of the Adriatic at the edge of the lagoons, about from the sea, on the river ...

in Northern Italy during the 4th century and it was carried into

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

as a loot by Gothic warriors or by trading. It is the most possible that the find from

Biertan is a result of plundering in Illyricum or Pannonia or in the Balkans anytime between the fourth and the sixth century and this artifact was reused as a pagan object by its new owners. Originally it was intended to be hung from a candelabrum but the perforations made later indicate it was reused and attached to a coffer for storing vessels or other goods. According to this opinion even its usage for Christian purposes should be questioned in the territory of

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

.

It is only in the 5th century that the artefacts become more common, most of them in the form of

oil lamps, gold rings with cross incisions (from

the tomb of Omahar in Apahida), a chest piece with Christian symbols. From the 6th century, associated with the missionary work supported by

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

and confirmed by their

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

provenience, the

oil lamps become even more common, accompanied by two

ampullae

An ampulla (; ) was, in Ancient Rome, a small round vessel, usually made of glass and with two handles, used for sacred purposes. The word is used of these in archaeology, and of later flasks, often handle-less and much flatter, for holy water or ...

with the representation of

Saint Menas, and several moulds for

cross shaped pendants.

In the context of Khan

Boris I

Boris I, also known as Boris-Mihail (Michael) and ''Bogoris'' ( cu, Борисъ А҃ / Борисъ-Михаилъ bg, Борис I / Борис-Михаил; died 2 May 907), was the ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire in 852–889. At ...

conversion to Christianity and the baptism of

Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely underst ...

, the

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

type of church organization is identified in the region. Historian I. Baán, discussing the origin of

Kalocsa archdiocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

, pointed that the existence of two archdioceses in the early days of

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

is connected with parallel work undertaken by missionaries from both the

Eastern and the

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

churches. He identifies archdiocese of

Kalocsa with "archdiocese of Tourkia" and lists in its suborder the dioceses of Transylvania, Banat, and Cenad. The baptism of

Gyula II Gyula II was a Hungarian tribal leader in the middle of the 10th century. He visited Constantinople, where he was baptized. His baptismal name was Stephen. Life

He descended from a family whose members held the hereditary title '' gyula'', which ...

in

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and his accompaniment by bishop Hierotheos lead to the deduction that the diocese of Transylvania was established before 1018. From this reasoning a diocese of Transylvania, subordinated to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, could be dated to the time of

Géza. His reasoning is sustained by the discovery in 2011 at

Alba Iulia

Alba Iulia (; german: Karlsburg or ''Carlsburg'', formerly ''Weißenburg''; hu, Gyulafehérvár; la, Apulum) is a city that serves as the seat of Alba County in the west-central part of Romania. Located on the Mureș River in the historica ...

of a church built in

Eastern tradition, and dated between the second half of the 10th century and first half of the 11th century.During the rule of

Ahtum (baptised in

Vidin

Vidin ( bg, Видин, ; Old Romanian: Diiu) is a port city on the southern bank of the Danube in north-western Bulgaria. It is close to the borders with Romania and Serbia, and is also the administrative centre of Vidin Province, as well as ...

) in Banat, towards the end of 10th century, a monastery of Eastern rite monks was active in

Cenad

Cenad ( hu, Nagycsanád, during the Dark Ages ''Marosvár''; german: Tschanad; sr, Чанад, Čanad; la, Chanadinum) is a commune in Timiș County, Romania. It is composed of a single village, Cenad. The village serves as a customs point on t ...

.

Gepids

After Attila's death, the Hunnic empire disintegrated. In 455 the Gepids (under king

Ardarich) conquered

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

, allowing them to settle for two centuries in Transylvania.

The

Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

secured their rule by attacking and ravaging their neighbors' territories and creating military border zones, while themselves remaining in Transylvania proper, surrounded by hard terrain. On one occasion in 539, cooperating with the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

they crossed the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

and devastated

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, killing ''

magister millitum''

Calluc. They weren't this lucky with the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

, who first routed the united forces of Gepids,

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

ans,

Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

ans and

Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

at the

Battle of Bolia

The Battle of Bolia, was a battle in 469 between the Ostrogoths ( Amal Goths) and a coalition of Germanic tribes in the Roman province of Pannonia. It was fought on the south side of the Danube near its confluence with the river Bolia, in pre ...

, than at the

Battle of Sirmium.

King Thraustila lost the city and his successors failed to recapture even after Theodoric's death.

After a long decline, Gepidia finally fell to the joint invasion of the

Avars and

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

in 567.

Very few Gepid sites (such as cemeteries in the

Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of ...

region) after 600 remain; they were apparently assimilated by the

Avar empire.

Avars, Slavs, Bulgars

By 568 the

Avars, under Khagan

Bayan I established an empire in the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

that lasted for 250 years. Related peoples from the east arrived in the

Avar Kaganate several times: around 595 the

Kutrigurs

Kutrigurs were Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished on the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the 6th century AD. To their east were the similar Utigurs and both possibly were closely related to the Bulgars. They warred with the Byzantine Empire and ...

, and then around 670 the

Onogurs.

During this period the

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

were allowed to settle inside

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

. The

Avars declined with the rise of

Charlemagne's Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

. After a war between the

khagan

Khagan or Qaghan (Mongolian:; or ''Khagan''; otk, 𐰴𐰍𐰣 ), or , tr, Kağan or ; ug, قاغان, Qaghan, Mongolian Script: ; or ; fa, خاقان ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan ...

and

Yugurrus from 796 to 803, the

Avars were defeated. The Transylvanian

Avars were subjugated by the

Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as noma ...

under

Khan Krum

Krum ( bg, Крум, el, Κροῦμος/Kroumos), often referred to as Krum the Fearsome ( bg, Крум Страшни) was the Khan of Bulgaria from sometime between 796 and 803 until his death in 814. During his reign the Bulgarian territor ...

at the beginning of the ninth century, after which the region was partially occupied by fleeing Slavs, who sought for protection from the Franks. Later, Southern Transylvania was conquered by the

First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire ( cu, блъгарьско цѣсарьствиѥ, blagarysko tsesarystviye; bg, Първо българско царство) was a medieval Bulgar- Slavic and later Bulgarian state that existed in Southeastern Eur ...

.

The downfall of the

Avar Khaganate

The Pannonian Avars () were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of various origins. The peoples were also known as the Obri in chronicles of Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai ( el, Βαρχονίτες, Varchonítes), or Pseudo-Avars ...

at the beginning of the 9th century did not mean the extinction of the

Avar population, contemporary written sources report surviving

Avar groups.

Hungarians

The

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

arrived in the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

, in a geographically unified but politically divided land, after acquiring thorough local knowledge of the area from the 860s onwards.

After the end of the

Avar Kaganate (c. 822), the

Eastern Franks asserted their influence in

Transdanubia

Transdanubia ( hu, Dunántúl; german: Transdanubien, hr, Prekodunavlje or ', sk, Zadunajsko :sk:Zadunajsko) is a traditional region of Hungary. It is also referred to as Hungarian Pannonia, or Pannonian Hungary.

Administrative divisions Trad ...

, the

Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely underst ...

to a small extent in the Southern

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

and the interior regions housed the surviving

Avar population in their stateless state.

According to the archaeological evidence, the

Avar population survived the time of the

Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin

The Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, also known as the Hungarian conquest or the Hungarian land-taking (), was a series of historical events ending with the settlement of the Hungarians in Central Europe in the late 9th and early 10t ...

.

In this power vacuum, The

Hungarian conqueror elite took the system of the former

Avar Kaganate, there is no trace of massacres and mass graves, it is believed to have been a peaceful transition for local residents in the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

.

In 862, Prince

Rastislav of Moravia

Rastislav or Rostislav, also known as St. Rastislav, (Latin: ''Rastiz'', Greek: Ῥασισθλάβος / ''Rhasisthlábos'') was the second known ruler of Moravia (846–870).Spiesz ''et al.'' 2006, p. 20. Although he started his reign as vass ...

rebelled against the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

, and after hiring

Magyar troops, won his independence; this was the first time that

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

expeditionary troops entered the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

. In 862, Archbishop

Hincmar of Reims records the campaign of unknown enemies called "Ungri", giving the first mention of the

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

in

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. In 881, the

Hungarian forces fought together with the Kabars in the

Vienna Basin

The Vienna Basin (german: Wiener Becken, cz, Vídeňská pánev, sk, Viedenská kotlina, Hungarian: ''Bécsi-medence'') is a geologically young tectonic burial basin and sedimentary basin in the seam area between the Alps, the Carpathians and t ...

. According to historian György Szabados and archeologist Miklós Béla Szőke, a group of

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

were already living in the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

at that time, so they could quickly intervene in the events of the

Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

.

The number of recorded battles increased from the end of the 9th century.

In the late

Avar period, a part of

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

was already present in the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

in the 9th century, this has been supported by genetic and archaeological research, because there are graves in which

Avar descendants are buried in

Hungarian clothes.

An important segment of this

Avar era

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

is that the

Hungarian county system of King

Saint Stephen I

Pope Stephen I ( la, Stephanus I) was the bishop of Rome from 12 May 254 to his death on 2 August 257.Mann, Horace (1912). "Pope St. Stephen I" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. He was later Canonizati ...

may be largely based on the power centers formed during the

Avar period.

Based on DNA evidence, the Proto-Hungarians admixed with

Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

and

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, this three genetic components appear in the graves of the

Hungarian conqueror elite of the 9th century.

Based on the DNA in the

Hungarian conqueror graves, the conquerors had eastern origin, but the vast majority of the

Hungarian conquerors had European genome.

The cemeteries of the

Hungarian commoners had fewer Asian genomes than the cemeteries of the

Hungarian elite.

According to the genetic evidence, there is a genetic continuity from the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, a continuous migration of the

Steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

folks from east to the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

.

The

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

took possession of the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

in a pre-planned manner, with a long move-in between 862–895.

According to eleventh-century tradition, the road taken by the

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

under Prince

Álmos took them first to

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

in 895. This is supported by an eleventh-century Russian tradition that the

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

moved to the

Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

by way of

Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

. Prince

Álmos, the sacred leader of the

Hungarian Great Principality died before he could reach

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

, he was sacrificed in

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

.

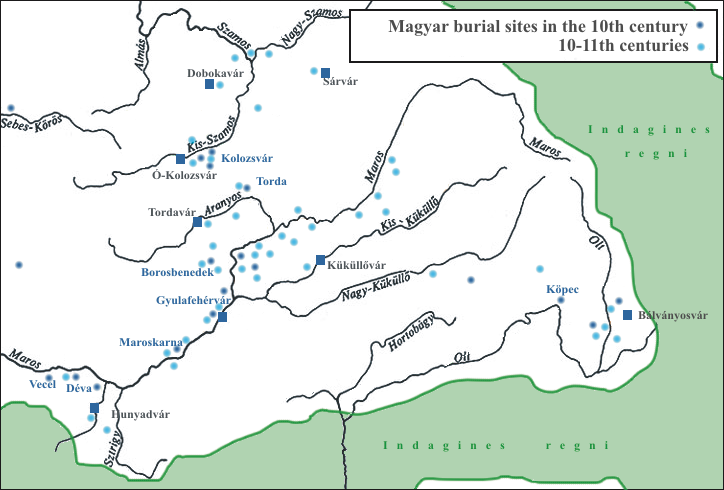

According to Romanian historian, Florin Curta no evidence exists of

Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic ...

crossing Eastern Carpathian Mountains into

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

.

According to supporters of the

Daco-Roman continuity theory,

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

was populated by

Romanians