Torsion siege engine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A torsion siege engine is a type of

A torsion siege engine is a type of

Preceding the development of torsion siege engines were tension siege engines that had existed since at least the beginning of the 4th century BC, most notably the gastraphetes in Heron of Alexandria's ''Belopoeica'' that was probably invented in Syracuse by

Preceding the development of torsion siege engines were tension siege engines that had existed since at least the beginning of the 4th century BC, most notably the gastraphetes in Heron of Alexandria's ''Belopoeica'' that was probably invented in Syracuse by

A common misconception about torsion siege engines such as the

A common misconception about torsion siege engines such as the

and 1 dactyl = 1.93 cm ''m'' is measured in Mina (unit), minas, and 1 mina = 437 g 1 talent = 60 mina = 26 kg

Espringal

from the anonymous Romance of Alexander, c. 14th century, MS Bodleian 264.

Espringal

from ''De re militari'' by Roberto Valturio, 1455.

Mangonel

from BL Royal 19 D I, f.111.

Onager

from Walter de Milemete's ''De nobilitatibus, sapientiis'', et prudentiis regum, 1326.]

Cheiroballista

behind fortifications, Trajan's Column, 1st century AD

Cheiroballista

mounted on wall, Trajan's Column.

Cheiroballista

hauled by horse, Trajan's Column.

Bronze Washers

from the Amparius catatpult, cited in Schramm.

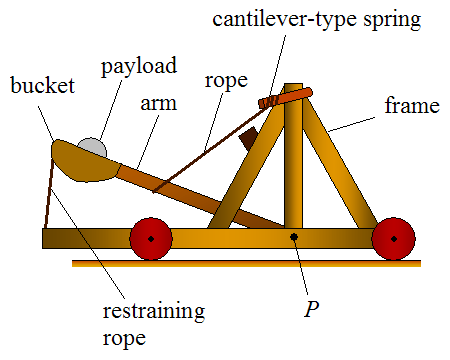

Catapult

with bucket.

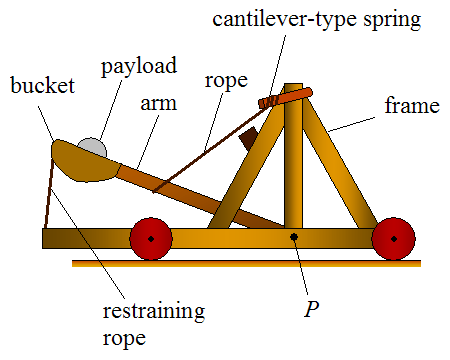

Catapult

with sling.

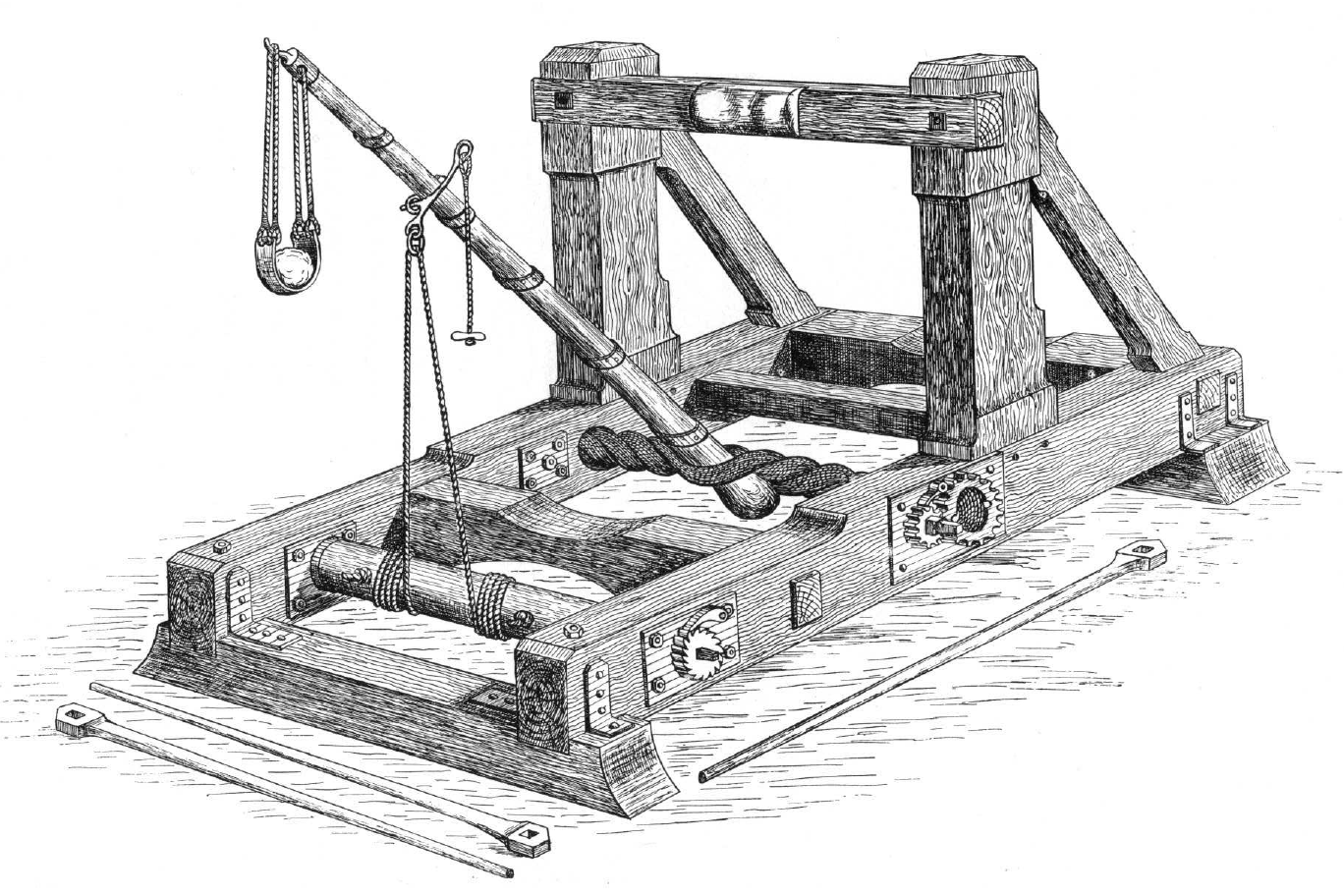

Onager

; Two-Armed Machines

Ballista

Euthytonon

Euthytonon

range of movement.

Oxybolos

Palintonon

Palintonon

side view.

Scorpion

Stone Thrower

Catapult

at the Stratford Armouries, Warwickshire, England.

Onager

at Felsenburg Neurathen, Saxony. ; Two-Armed Machine

Ballista

at

Ballista

at

Cheiroballista

# Espringa

side view

an

rear view

Polybolos & cheiroballista

Arsenal of ancient mechanical artillery in the

Roman Ballista

in the Hecht Museum, Haifa.

Roman Ballista

Zayir

at Trebuchet Park,

Book X, §10

; Secondary sources * Baatz, Dietwulf. “Recent Finds of Ancient Artillery.” ''Britannia'', 9 (1978): 1-17. * Bachrach, Bernard S. “Medieval Siege Warfare: A Reconnaissance.” ''The Journal of Military History'', 58 #1 (January 1994): 119-133. * Bradbury, Jim. ''The Medieval Siege''. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1992. * Chevedden, Paul E. “Artillery in Late Antiquity: Prelude to the Middle Ages,” in ''The Medieval City under Siege'', edited by Ivy A. Corfis and Michael Wolfe, pp. 131–176. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1995. * Cuomo, Serafina. “The Sinews of War: Ancient Catapults.” ''Science'', New Series, 303 #5659 (February 6, 2004): 771-772. * DeVries, Kelly. ''Medieval Military Technology''. Ontario: Broadview Press, 1992. * DeVries, Kelly & Robert D. Smith. ''Medieval Weapons: An Illustrated History of their Impact''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc, 2007. * Dufour, Guillaume. ''Mémoire sur l’artillerie des anciens et sur celle de Moyen Âge''. Paris: Ab. Cherbuliez et Ce,1840). * * Gravett, Christophers. ''Medieval Siege Warfare''. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Ltd, 1990, 2003. * Hacker, Barton C. “Greek Catapults and Catapult Technology: Science, Technology, and War in the Ancient World.” ''Technology and Culture'', 9 #1 (January 1968): 34-50. * Huuri, Kalervo. “Zur Geschichte de mittelalterlichen Geschützwesens aus orientalischen Quellen,” in ''Societas Orientalia Fennica, Studia Orientalia'' 9.3 (1941): pp. 50–220. * Johnson, Stephen. ''Late Roman Fortifications''. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble Books, 1983. * Köhler, G. ''Die Entwickelung des Kriegwesens und der Kriegfürung in der Ritterseit von Mitte des II. Jahrhundert bis du Hussitenkriegen'', Vol. 3. Breslau: Verlag von Wilhelm Koebner, 1890. * Landels, J.G. ''Engineering in the Ancient World''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978. * Marsden, E.W. ''Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969. * Nicholson, Helen. ''Medieval Warfare: Theory and Practice of War in Europe, 300-1500''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. * Nossov, Konstantin. ''Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons: A Fully Illustrated Guide to Siege Weapons and Tactics''. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2005. * Reinschmidt, Kenneth F. “Catapults of Yore.” ''Science'', New Series, 304 #5675 (May 28, 2004): 1247. * Rihill, Tracey. ''The Catapult: A History''. Yardley, PA: Wesholme Publishing, LLC, 2007. * Rihill, Tracey. “On Artillery Towers and Catapult Sizes.” ''The Annual of the British School at Athens'', 101 (2006): 379-383. * Rogers, Randall. ''Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. * Roland, Alex. “Science, Technology, and War.” ''Technology and Culture'', 36 #2, Supplement: Snapshots of a Discipline: Selected Proceedings from the Conference on Critical Problems and Research Frontiers in the History of Technology, Madison, Wisconsin, October 30-November 3, 1991 (April 1995): S83-100. * Schneider, Rudolf. ''Die Artillerie des Mittelalters''. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1910. * Tarver, W.T.S. “The Traction Trebuchet: A Reconstruction of an Early Medieval Siege Engine.” ''Technology and Culture'', 36 #1 (January 1995): 136-167. * Thompson, E.A. “Early Germanic Warfare.” Past and Present, 14 (November 1958): 2-29.

On Military Matters (De Gestae, Latin)

On Military Matters (De Gestae, English)

On Military Matters (De Gestae, Latin & English) ; Athenaeus Mechanicus

On Machines (Περὶ μηχανημάτων, Greek & English)

On Machines (Περὶ μηχανημάτων, Greek & Latin, partial text) ; De rebus bellicis

De Rebus Bellicis (Latin) ; Heron of Alexandria

On Artillery (Belopoiika/Belopoeica/βελοποιικά, Greek) ; Philon of Byzantium

On Artillery (Belopoiika/Belopoeica/βελοποιικά, Greek & German) ; Procopius

The Wars of Justinian (Ὑπέρ τῶν πολέμων λόγοι, Greek)

The Wars of Justinian (Ὑπέρ τῶν πολέμων λόγοι, Greek)

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1676

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English)

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English)

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English) ; Vegetius

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, Latin)

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, English)

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, English) ; Vitruvius

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin & English)

On Architecture (De Architectura, English)

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin)

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin) {{Authority control Ancient artillery

A torsion siege engine is a type of

A torsion siege engine is a type of siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

that utilizes torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bi ...

to launch projectiles. They were initially developed by the ancient Macedonians, specifically Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

and Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, and used through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

until the development of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

artillery in the 14th century rendered them obsolete.

History

Greek

Preceding the development of torsion siege engines were tension siege engines that had existed since at least the beginning of the 4th century BC, most notably the gastraphetes in Heron of Alexandria's ''Belopoeica'' that was probably invented in Syracuse by

Preceding the development of torsion siege engines were tension siege engines that had existed since at least the beginning of the 4th century BC, most notably the gastraphetes in Heron of Alexandria's ''Belopoeica'' that was probably invented in Syracuse by Dionysius the Elder

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder ( 432 – 367 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, in Sicily. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western Gre ...

. Though simple torsion devices could have been developed earlier, the first extant evidence of a torsion siege engine comes from the Chalcotheca, the arsenal on the Acropolis in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, and dates to c. 338 - 326 BC. It lists the building's inventory that included torsion catapults and its components such as hair springs, catapult bases, and bolts. The transition from tension machines to torsion machines is a mystery, though E.W. Marsden speculates that a reasonable transition would involve the recognition of the properties of sinew in previously existing tension devices and other bows. Torsion based weaponry offered much greater efficiency over tension based weaponry. Traditional historiography puts the speculative date of the invention of two-armed torsion machines during the reign of Philip II of Macedon circa 340 BC, which is not unreasonable given the earliest surviving evidence of siege engines stated above.

The machines quickly spread throughout the ancient Mediterranean, with schools and contests emerging at the end of the 4th century BC that promoted the refinement of machine design. They were so popular in ancient Greece and Rome that competitions were often held. Students from Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greece, Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a se ...

, Ceos

Kea ( el, Κέα), also known as Tzia ( el, Τζια) and in antiquity Keos ( el, Κέως, la, Ceos), is a Greek island in the Cyclades archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Kea is part of the Kea-Kythnos regional unit.

Geography

It is the island of ...

, Cyanae, and especially Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

were highly sought after by military leaders for their catapult construction. Torsion machines in particular were used heavily in military campaigns. Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon ag ...

, for example, used torsion engines during his campaigns in 219-218 BC, including 150 sharp-throwers and 25 stone-throwers. Scipio Africanus confiscated 120 large catapults, 281 small catapults, 75 ballistae, and a great number of scorpions

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always end ...

after he captured New Carthage in 209 BC.

Roman

The Romans obtained their knowledge of artillery from the Greeks. In ancient Roman tradition, women were supposed to have given up their hair for use in catapults, which has a later example in Carthage in 148-146 BC. Torsion artillery, especially ballistae came into heavy usage during the First Punic War and was so common by the Second Punic War thatPlautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the ...

remarked in the '' Captivi'' that “Meus est ballista pugnus, cubitus catapulta est mihi” (“The ballista is my fist, the catapult is my elbow").

By 100 AD, the Romans had begun to permanently mount artillery, whereas previously machines had traveled largely disassembled in carts. Romans made the Greek ballista more portable, calling the hand-held version manuballista

The ''cheiroballistra'' ( el, χειροβαλλίστρα) or ''manuballista'' (Latin), which translates in all its forms to "hand ballista", was an imperial-era Roman siege engine. Designed by Hero of Alexandria and mostly composed of metal (t ...

and the cart-mounted type carroballista. They also made use of a one armed torsion stone-projector named the onager

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

. The earliest extant evidence of the carroballista is on Trajan's Column

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Ap ...

. Between 100 and 300 AD, every Roman legion had a battery of ten onagers and 55 cheiroballistae hauled by teams of mules. After this, there were legionaries called ballistarii whose exclusive purpose was to produce, move, and maintain catapults.

In later antiquity the onager

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

began to replace the more complicated two-armed devices. The Greeks and Romans, with advanced methods of military supply and armament, were able to readily produce the many pieces needed to build a ballista. In the later 4th and 5th centuries as these administrative structures began to change, simpler devices became preferable because the technical skills needed to produce more complex machines were no longer as common. Vegetius

Publius (or Flavius) Vegetius Renatus, known as Vegetius (), was a writer of the Later Roman Empire (late 4th century). Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what is contained in his two surviving works: ''Epitoma rei militaris'' (also r ...

, Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquity (preceding Procopius). His work, known as the ''Res Gestae ...

, and the anonymous "De rebus bellicis

''De rebus bellicis'' ("On the Things of Wars") is an anonymous work of the 4th or 5th century which suggests remedies for the military and financial problems in the Roman Empire, including a number of fanciful war machines. It was written af ...

" are our first and most descriptive sources on torsion machines, all writing in the 4th century AD. A little later, in the 6th century, Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

provides his description of torsion devices. All use the term ballistae and provide descriptions similar to those of their predecessors.

Medieval continuity

A common misconception about torsion siege engines such as the

A common misconception about torsion siege engines such as the ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ...

or onager

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

is their continued usage after the beginning of the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

(late 5th-10th centuries AD). These artillery weapons were only used in the West until the 6-8th centuries, when they were replaced by the traction trebuchet, more commonly known as the mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel o ...

. The myth of the torsion mangonel began in the 18th century when Francis Grose claimed that the onager was the dominant medieval artillery until the arrival of gunpowder. In the mid-19th century, Guillaume Henri Dufour adjusted this framework by arguing that onagers went out of use in medieval times, but were directly replaced by the counterweight trebuchet. Dufour and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte argued that torsion machines were abandoned because the requisite supplies needed to build the sinew skein and metal support pieces were too difficult to obtain in comparison to the materials needed for tension and counterweight machines. In the early 20th century, Ralph Frankland-Payne-Gallwey concurred that torsion catapults were not used in medieval times, but only owing to their greater complexity, and believed that they were superior to "such a clumsy engine as the medieval trebuchet." Others such as General Köhler disagreed and argued that torsion machines were used throughout the Middle Ages. The torsion mangonel myth is particularly appealing for many historians due to its potential as an argument for the continuity of classical technologies and scientific knowledge into the Early Middle Ages, which they use to refute the concept of medieval decline.

It was only in 1910 that Rudolph Schneider pointed out that medieval Latin texts are completely devoid of any description of the torsion mechanism. He proposed that all medieval terms for artillery actually referred to the trebuchet, and that the knowledge to build torsion engines had been lost since classical times. In 1941, Kalervo Huuri argued that the onager remained in use in the Mediterranean region, but not ballistas, until the 7th century when "its employment became obscured in the terminology as the traction trebuchet came into use."

Some historians such as Randall Rogers and Bernard Bachrach have argued that the lack of evidence regarding torsion siege engines does not provide enough proof that they were not used, considering that the narrative accounts of these machines almost always do not provide enough information to definitively identify the type of device being described, even with illustrations. However by the 9th century, when the first Western European reference to a ''mangana'' (mangonel) appeared, there is virtually no evidence at all, whether textual or artistic, of torsion engines used in warfare. The last historical texts specifying a torsion engine, aside from bolt throwers such as the springald, date no later than the 6th century. Illustrations of an onager do not reappear until the 15th century. With the exception of bolt throwers such as the springald

A springald, or espringal, was a medieval torsion artillery device for throwing bolts. It is depicted in a diagram in an 11th-century Byzantine manuscript, but in Western Europe is more evident in the late 12th century and early 13th century. It w ...

which saw action from the 13th to 14th centuries or the ''ziyar'' in the Muslim world, torsion machines had largely disappeared by the 6th century and were replaced by the traction trebuchet. This does not mean torsion machines were completely forgotten since classical texts describing them were circulated in medieval times. For example, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou had a copy of Vegetius

Publius (or Flavius) Vegetius Renatus, known as Vegetius (), was a writer of the Later Roman Empire (late 4th century). Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what is contained in his two surviving works: ''Epitoma rei militaris'' (also r ...

at the siege of Montreuil-Bellay in 1147, yet judging from the description of the siege, the weapon they used was a traction trebuchet rather than a torsion catapult.

Contributing to the torsion mangonel myth is the muddled usage of the term ''mangonel''. ''Mangonel'' was used as a general medieval catch-all for stone throwing artillery, which probably meant a ''traction trebuchet'' from the 6th to 12th centuries, between the disappearance of the onager and the arrival of the counterweight trebuchet. However many historians have argued for the continued use of onagers into medieval times by wading into terminological thickets. For example at the end of the 19th century, Gustav Köhler contended that the petrary was a traction trebuchet, invented by Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, whereas the mangonel was a torsion catapult. Even disregarding definition, sometimes when the original source specifically used the word "mangonel," it was translated as a torsion weapon such as the ballista instead, which was the case with an 1866 Latin translation of a Welsh text. This further adds to the confusion in terminology since "ballista" was used in medieval times as well, but probably only as a general term for stone throwing machines. For example Otto of Freising

Otto of Freising ( la, Otto Frisingensis; c. 1114 – 22 September 1158) was a German churchman of the Cistercian order and chronicled at least two texts which carries valuable information on the political history of his own time. He was Otto I ...

referred to the mangonel as a type of ballista, by which he meant they both threw stones. There are also references to Arabs, Saxons, and Franks using ballistae but it is never specified whether or not these were torsion machines. It is stated that during the siege of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

in 885-886, when Rollo

Rollo ( nrf, Rou, ''Rolloun''; non, Hrólfr; french: Rollon; died between 928 and 933) was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, today a region in northern France. He emerged as the outstanding warrior among the Norsemen who had se ...

pitted his forces against Charles the Fat

Charles III (839 – 13 January 888), also known as Charles the Fat, was the emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 881 to 888. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, Charles was the youngest son of Louis the German and Hemma, and a great-grandso ...

, seven Danes were impaled at once with a bolt from a ''funda''. Even in this instance it is never stated that the machine was torsion, as was the case with uses of other terminology such as ''mangana'' by William of Tyre

William of Tyre ( la, Willelmus Tyrensis; 113029 September 1186) was a medieval prelate and chronicler. As archbishop of Tyre, he is sometimes known as William II to distinguish him from his predecessor, William I, the Englishman, a former ...

and Willam the Breton, used to indicate small stone-throwing engines, or "cum cornu" ("with horns") in 1143 by Jacques de Vitry.

In modern times the mangonel is often confused with the onager due to the torsion mangonel myth. Modern military historians came up with the term "traction trebuchet" to distinguish it from previous torsion machines such as the onager. However ''traction trebuchet'' is a newer modern term that is not found in contemporary sources, which can lead to further confusion. For some, the mangonel is not a specific type of siege weapon but a general term for any pre-cannon stone throwing artillery. Onagers have been called onager mangonels and traction trebuchets called "beam-sling mangonel machines". From a practical perspective, mangonel has been used to describe anything from a torsion engine like the onager, to a traction trebuchet, to a counterweight trebuchet depending on the user's bias.

Construction

Design

In early designs, machines were made with square wooden frames with holes drilled in the top and bottom through which a skein was threaded, wrapped around wooden levers that spanned the holes, enabling the adjustment of tension. The problem with this design is that when increasing the tension of the skein, turning the lever became nigh impossible because of the friction caused by the contact made between the wood of the lever and the wood of the frame. This problem was solved simply with the addition of metal washers inserted in the holes of the frames and fastened either with tenons or rims which enabled greater control over the machine's tension and the maximization of its power without sacrificing the integrity of the frame. Further design modifications that became standard include combining the two separate spring frames into a single unit to increase durability and stability, the addition of a padded heel block to stop the recoil of the machine, the development of formulae to determine the appropriate engine size (see Construction & Measurements below), and a ratcheting trigger mechanism that made it quicker to fire the machine. Marsden suggests that all of these initial developments occurred in fairly rapid succession, potentially over the span of just a few decades, because the deficiencies in design were fairly obvious problems. Thereon, a gradual refinement over the succeeding centuries provided the adjustments given in the chart below. Marsden's description of torsion machine development follows the general course thatHeron of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἥρων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, ''Heron ho Alexandreus'', also known as Heron of Alexandria ; 60 AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in his native city of Alexandria, Roman Egypt. He i ...

lays out, but the Greek writer does not give any dates, either. Marsden's chart below gives his best approximations of the dates of machine development.

Only a few specific designs of torsion catapults are known from ancient and medieval history. The materials used are just as vague, other than stating wood or metal were used as building materials. The skein that comprised the spring, on the other hand, has been cited specifically as made of both animal sinew and hair, either women's and horse. Heron and Vegetius consider sinew to be better, but Vitruvius cites women's hair as preferable. The preferred type of sinews came from the feet of deer (assumedly achilles tendons because they were longest) and the necks of oxen (strong from constant yoking). How it was made into a rope is not known, though J.G. Landels argues it was likely frayed on the ends, then woven together. The ropes, either hair or sinew were treated with olive oil and animal grease/fat to preserve its elasticity. Landels additionally argues that the energy-storing capacity of sinew is much greater than a wooden beam or bow, especially considering that wood's performance in tension devices is severely affected by temperatures above 77 degrees Fahrenheit, which was not uncommon in a Mediterranean climate.

Measurements

Two general formulas were used in determining the size of the machine and the projectile it throws. The first is to determine the length of the bolt for a sharp-thrower, given as ''d = x / 9'', where ''d'' is the diameter of the hole in the frame where the skein was threaded and ''x'' is the length of the bolt to be thrown. The second formula is for a stone thrower, given as , where ''d'' is the diameter of the hole in the frame where the skein was threaded and ''m'' is the weight of the stone. The reason for the development of these formulas is to maximize the potential energy of the skein. If it was too long, the machine could not be used at its full capacity. Furthermore, if it was too short, the skein produced a high amount of internal friction that would reduce the durability of the machine. Finally, being able to accurately determine the diameter of the frame's holes prevented the sinews and fibers of the skein from being damaged by the wood of the frame. Once these initial measurements were made, corollary formulae could be used to determine the dimensions of the rest of the machines. A couple of examples below serve to illustrate this: ''d'' is measured in dactyland 1 dactyl = 1.93 cm ''m'' is measured in Mina (unit), minas, and 1 mina = 437 g 1 talent = 60 mina = 26 kg

Effective use

No definitive results have been obtained through documentation or experiment that can accurately verify claims made in manuscripts concerning the range and damaging capabilities of torsion machines. The only way to do so would be to construct a whole range of full-scale devices using period techniques and supplies to test the legitimacy of individual design specifications and their effectiveness of their power. Kelly DeVries and Serafina Cuomo claim torsion engines needed to be about 150 meters or closer to their target to be effective, though this is based on literary evidence, too. Athenaeus Mechanicus cites a three-span catapult that could propel a shot 700 yards. Josephus cites an engine that could hurl a stone ball 400 yards or more, and Marsden claims that most engines were probably effective up to the distance cited by Josephus, with more powerful machines capable of going farther. Of the projectiles used, exceptionally large ones have been mentioned in accounts, but "most Hellenistic projectiles found in the Near East weigh less than 15 kg and most dating to the Roman period weigh less than 5 kg." The obvious disadvantage to any device powered primarily by animal tissue is that they had the potential to deteriorate rapidly and be severely affected by changing weather. Another issue was that the rough surface of the wooden frames could easily damage the sinew of the skein, and on the other hand the force of the tension provided by the skein could potentially damage the wooden frame. The solution was to place washers inside the holes of the frame through which the skein was threaded. This prevented damage to the skein, increased the structural integrity of the frame, and allowed engineers to precisely adjust tension levels using evenly spaced holes on the outer rim of the washers. The skein itself could be made out of human or animal hair, but it was most commonly made out of animal sinew, which Heron cites specifically. Life of the sinew has been estimated to be about eight to ten years, which made them expensive to maintain. What is known is that they were used to provide covering fire while the attacking army was assaulting a fortification, filling in a ditch, and bringing other siege engines up to walls. Jim Bradbury goes so far as to claim torsion engines were only useful against personnel, primarily because medieval torsion devices were not powerful enough to batter down walls.Archaeological evidence

Archaeological evidence for catapults, especially torsion devices, is rare. It is easy to see how stones from stone-throwers could survive, but organic sinews and wooden frames quickly deteriorate if left unattended. Usual remains include the all-important washers, as well as other metal supporting pieces, such as counterplates and trigger mechanisms. Still, the first major evidence of ancient or medieval catapults was found in 1912 in Ampurias. It was not until 1968-1969 that new catapult finds were discovered at Gornea and Orşova, then again in 1972 in Hatra, with more frequent discoveries thereafter.Stone projectiles

The sites below contained stone projectiles ranging in size from 10-90 minas (c. 4.5–39 kg). *5,600 balls in Carthage (Tunisia) *961 balls in Pergamum (Turkey) *353 balls in Rhodes (Greece) *>200 balls in Tel Dor (Israel) *c. 200 balls in Salamis (Cyprus)Catapult remains

NOTE: This list is not meant to be comprehensive. It is meant to show the widespread use of catapults in the Western world.Literary evidence

The literary examples of torsion machines are too numerous to cite here. Below are a few well-known examples to provide a general perspective held by contemporaries.Examples

;Diodorus of Sicily

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, ''History'', 14.42.1, 43.3., 50.4, c. 30 - 60 BC

"As a matter of fact, the catapult was invented at this time 99 BC

__NOTOC__

Year 99 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Antonius and Albinus (or, less frequently, year 655 ''Ab urbe condita'') and the Second Year of Tianhan. The denomination ...

in Syracuse, for the greatest technical minds from all over had been assembled in one place...The Syracusans killed many of their enemies by shooting them from the land with catapults that shot sharp-pointed missiles. In fact this piece of artillery caused great consternation, since it had not been known before this time."

; Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, ''The Wars of the Jews'', 67 AD

"The force with which these weapons threw stones and darts was such that a single projectile ran through a row of men, and the momentum of the stone hurled by the engine carried away battlements and knocked off corners of towers. There is in fact no body of men so strong that it cannot be laid low to the last rank by the impact of these huge stones...Getting in the line of fire, one of the men standing near Josephus he commander of Jotapata, not the historian

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' i ...

on the rampart had his head knocked off by a stone, his skull being flung like a pebble from a sling more than 600 meters; and when a pregnant woman on leaving her house at daybreak was struck in the belly, the unborn child was carried away 100 meters."

; Procopius, ''The Wars of Justinian'', 537-538 AD

"...at the Salerian Gate a Goth of goodly statue and a capable warrior, wearing a corselet and having a helmet on his head, a man who was of no mean station in the Gothic nation...was hit by a missile from an engine which was on a tower at this left. And passing through the corselet and the body of the man, the missile sank more than half its length into the tree, and pinning him to the spot where it entered the tree, it suspended him there a corpse."

Images

Manuscripts

Espringal

from the anonymous Romance of Alexander, c. 14th century, MS Bodleian 264.

Espringal

from ''De re militari'' by Roberto Valturio, 1455.

Mangonel

from BL Royal 19 D I, f.111.

Onager

from Walter de Milemete's ''De nobilitatibus, sapientiis'', et prudentiis regum, 1326.]

Iconography

Cheiroballista

behind fortifications, Trajan's Column, 1st century AD

Cheiroballista

mounted on wall, Trajan's Column.

Cheiroballista

hauled by horse, Trajan's Column.

Bronze Washers

from the Amparius catatpult, cited in Schramm.

Diagrams

; One-Armed MachinesCatapult

with bucket.

Catapult

with sling.

Onager

; Two-Armed Machines

Ballista

Euthytonon

Euthytonon

range of movement.

Oxybolos

Palintonon

Palintonon

side view.

Scorpion

Stone Thrower

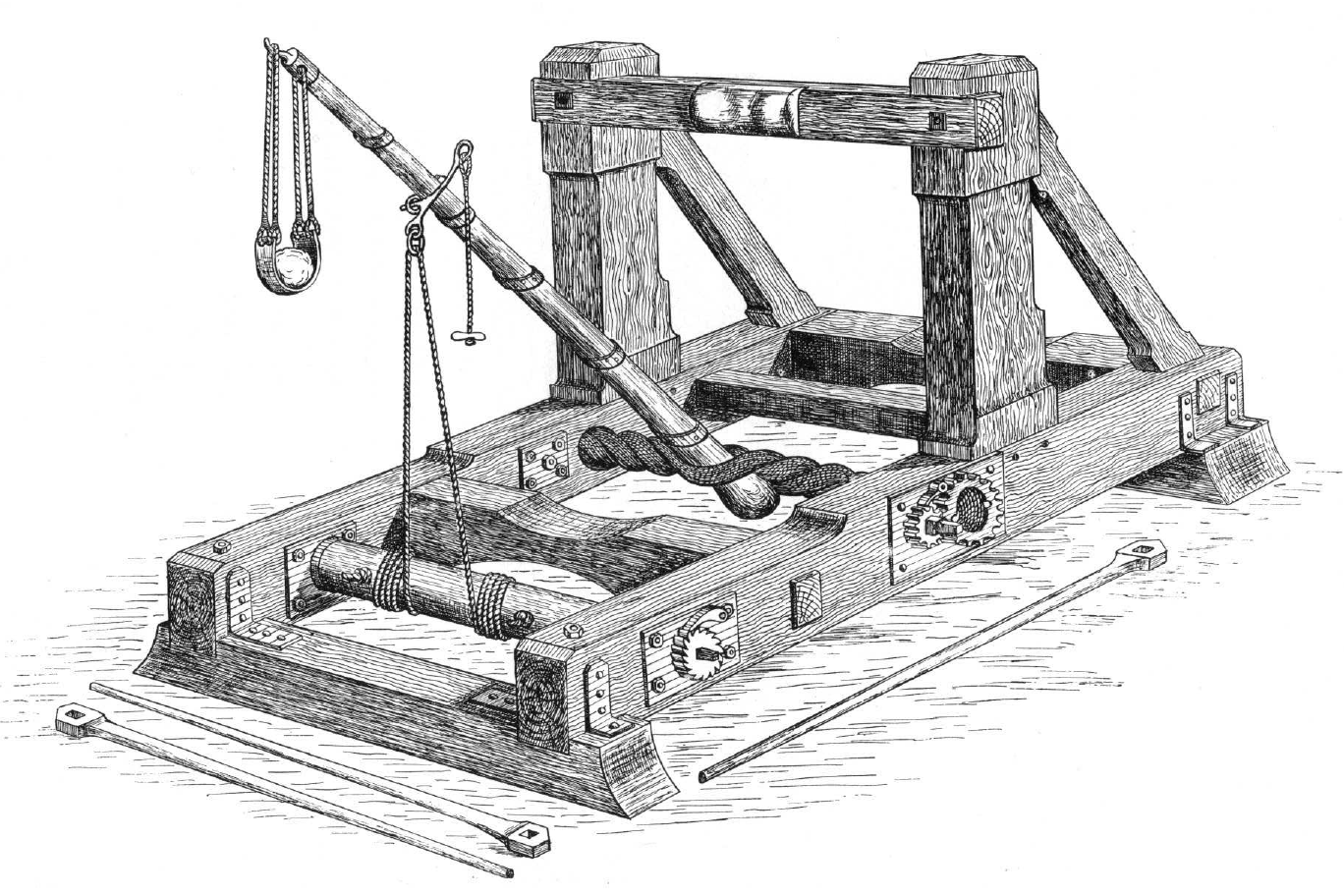

Reproductions

; One-Armed MachinesCatapult

at the Stratford Armouries, Warwickshire, England.

Onager

at Felsenburg Neurathen, Saxony. ; Two-Armed Machine

Ballista

at

Caerphilly Castle

Caerphilly Castle ( cy, Castell Caerffili) is a medieval fortification in Caerphilly in South Wales. The castle was constructed by Gilbert de Clare in the 13th century as part of his campaign to maintain control of Glamorgan, and saw extensi ...

, Wales.

Ballista

at

Warwick Castle

Warwick Castle is a medieval castle developed from a wooden fort, originally built by William the Conqueror during 1068. Warwick is the county town of Warwickshire, England, situated on a meander of the River Avon. The original wooden motte-an ...

, England.

Cheiroballista

# Espringa

side view

an

rear view

Polybolos & cheiroballista

Arsenal of ancient mechanical artillery in the

Saalburg

The Saalburg is a Roman fort located on the main ridge of the Taunus, northwest of Bad Homburg, Hesse, Germany. It is a cohort fort, part of the Limes Germanicus, the Roman linear border fortification of the German provinces. The Saalburg, ...

, Germany. Reconstructions made by the German engineer Erwin Schramm (1856-1935) in 1912.

Roman Ballista

in the Hecht Museum, Haifa.

Roman Ballista

Zayir

at Trebuchet Park,

Albarracín

Albarracín () is a Spanish town, in the province of Teruel, part of the autonomous community of Aragon. According to the 2007 census (INE), the municipality had a population of 1075 inhabitants. Albarracín is the capital of the mountainous Sier ...

, Spain.

Terminology

There is controversy over the terminology used to describe siege engines of every kind, including torsion machines. It is frustrating to scholars because the manuscripts are both vague in their descriptions of the machines and inconsistent in their usage of the terms. Additionally, in those few instances where torsion engines are identifiable, it is never certain which specific type of machine is being cited. Some scholars argue this abundance of terms indicates that torsion devices were in widespread use during the Middle Ages, though others argue that it is this very confusion about machine terminology that proves the few ancient texts that survived in the Latin West did not provide adequate information for the continuation of ancient torsion machines. The list below provides terms that have been found in reference to torsion engines in the ancient and medieval eras, but their specific definitions are largely inconclusive.Bradbury, 251,254; Hacker, 41; Nossov, 133, 155; Ammianus, 23.4.1-7; Tarver, 143.Notes

Bibliography

; Primary Sources (see also External Links below) * Humphrey, J.W., J.P. Olson, and A.N. Sherwood. ''Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook''. London: Routledge, 1998. * * Marsden, E.W. ''Greek and Roman Artillery: Technical Treatises''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. * * Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. * * * Philon of Byzantium. ''Philons Belopoiika (viertes Buch der Mechanik)''. Berlin: Verlag der Aakademie der Wissenschaften, 1919. * * * Vitruvius. ''On Architecture''. Accessed April 28, 2013Book X, §10

; Secondary sources * Baatz, Dietwulf. “Recent Finds of Ancient Artillery.” ''Britannia'', 9 (1978): 1-17. * Bachrach, Bernard S. “Medieval Siege Warfare: A Reconnaissance.” ''The Journal of Military History'', 58 #1 (January 1994): 119-133. * Bradbury, Jim. ''The Medieval Siege''. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1992. * Chevedden, Paul E. “Artillery in Late Antiquity: Prelude to the Middle Ages,” in ''The Medieval City under Siege'', edited by Ivy A. Corfis and Michael Wolfe, pp. 131–176. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1995. * Cuomo, Serafina. “The Sinews of War: Ancient Catapults.” ''Science'', New Series, 303 #5659 (February 6, 2004): 771-772. * DeVries, Kelly. ''Medieval Military Technology''. Ontario: Broadview Press, 1992. * DeVries, Kelly & Robert D. Smith. ''Medieval Weapons: An Illustrated History of their Impact''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc, 2007. * Dufour, Guillaume. ''Mémoire sur l’artillerie des anciens et sur celle de Moyen Âge''. Paris: Ab. Cherbuliez et Ce,1840). * * Gravett, Christophers. ''Medieval Siege Warfare''. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Ltd, 1990, 2003. * Hacker, Barton C. “Greek Catapults and Catapult Technology: Science, Technology, and War in the Ancient World.” ''Technology and Culture'', 9 #1 (January 1968): 34-50. * Huuri, Kalervo. “Zur Geschichte de mittelalterlichen Geschützwesens aus orientalischen Quellen,” in ''Societas Orientalia Fennica, Studia Orientalia'' 9.3 (1941): pp. 50–220. * Johnson, Stephen. ''Late Roman Fortifications''. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble Books, 1983. * Köhler, G. ''Die Entwickelung des Kriegwesens und der Kriegfürung in der Ritterseit von Mitte des II. Jahrhundert bis du Hussitenkriegen'', Vol. 3. Breslau: Verlag von Wilhelm Koebner, 1890. * Landels, J.G. ''Engineering in the Ancient World''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978. * Marsden, E.W. ''Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969. * Nicholson, Helen. ''Medieval Warfare: Theory and Practice of War in Europe, 300-1500''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. * Nossov, Konstantin. ''Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons: A Fully Illustrated Guide to Siege Weapons and Tactics''. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2005. * Reinschmidt, Kenneth F. “Catapults of Yore.” ''Science'', New Series, 304 #5675 (May 28, 2004): 1247. * Rihill, Tracey. ''The Catapult: A History''. Yardley, PA: Wesholme Publishing, LLC, 2007. * Rihill, Tracey. “On Artillery Towers and Catapult Sizes.” ''The Annual of the British School at Athens'', 101 (2006): 379-383. * Rogers, Randall. ''Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. * Roland, Alex. “Science, Technology, and War.” ''Technology and Culture'', 36 #2, Supplement: Snapshots of a Discipline: Selected Proceedings from the Conference on Critical Problems and Research Frontiers in the History of Technology, Madison, Wisconsin, October 30-November 3, 1991 (April 1995): S83-100. * Schneider, Rudolf. ''Die Artillerie des Mittelalters''. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1910. * Tarver, W.T.S. “The Traction Trebuchet: A Reconstruction of an Early Medieval Siege Engine.” ''Technology and Culture'', 36 #1 (January 1995): 136-167. * Thompson, E.A. “Early Germanic Warfare.” Past and Present, 14 (November 1958): 2-29.

External links

; Ammianus MarcellinusOn Military Matters (De Gestae, Latin)

On Military Matters (De Gestae, English)

On Military Matters (De Gestae, Latin & English) ; Athenaeus Mechanicus

On Machines (Περὶ μηχανημάτων, Greek & English)

On Machines (Περὶ μηχανημάτων, Greek & Latin, partial text) ; De rebus bellicis

De Rebus Bellicis (Latin) ; Heron of Alexandria

On Artillery (Belopoiika/Belopoeica/βελοποιικά, Greek) ; Philon of Byzantium

On Artillery (Belopoiika/Belopoeica/βελοποιικά, Greek & German) ; Procopius

The Wars of Justinian (Ὑπέρ τῶν πολέμων λόγοι, Greek)

The Wars of Justinian (Ὑπέρ τῶν πολέμων λόγοι, Greek)

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1676

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English)

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English)

The Wars of Justinian (De Bellis, English) ; Vegetius

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, Latin)

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, English)

On Military Matters (De Re Militari, English) ; Vitruvius

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin & English)

On Architecture (De Architectura, English)

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin)

On Architecture (De Architectura, Latin) {{Authority control Ancient artillery