Torridonian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

Their outcrop extends in a belt of variable breadth from

Their outcrop extends in a belt of variable breadth from

''Sea of the Hebrides''

Eds. P. Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC.

The Torridon Group infills an irregular land surface with up to 600 m of topography locally, cutting down through the previously deposited Stoer group sediments, resting in many areas directly on the Lewisian. It has been suggested that there is significant unconformity within this group, between the Diabaig and Applecross Formations.

The Torridon Group infills an irregular land surface with up to 600 m of topography locally, cutting down through the previously deposited Stoer group sediments, resting in many areas directly on the Lewisian. It has been suggested that there is significant unconformity within this group, between the Diabaig and Applecross Formations.

This formation is similar to the Applecross formation except that the sandstones are fine to medium-grained and there are very few pebbles. Almost all of these sandstone beds show the contortions shown by the older formation.

The Applecross and Aultbea Formations together consist of an overall fining-upward sequence of sandstones. Only the outcrops at

This formation is similar to the Applecross formation except that the sandstones are fine to medium-grained and there are very few pebbles. Almost all of these sandstone beds show the contortions shown by the older formation.

The Applecross and Aultbea Formations together consist of an overall fining-upward sequence of sandstones. Only the outcrops at

In

In geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

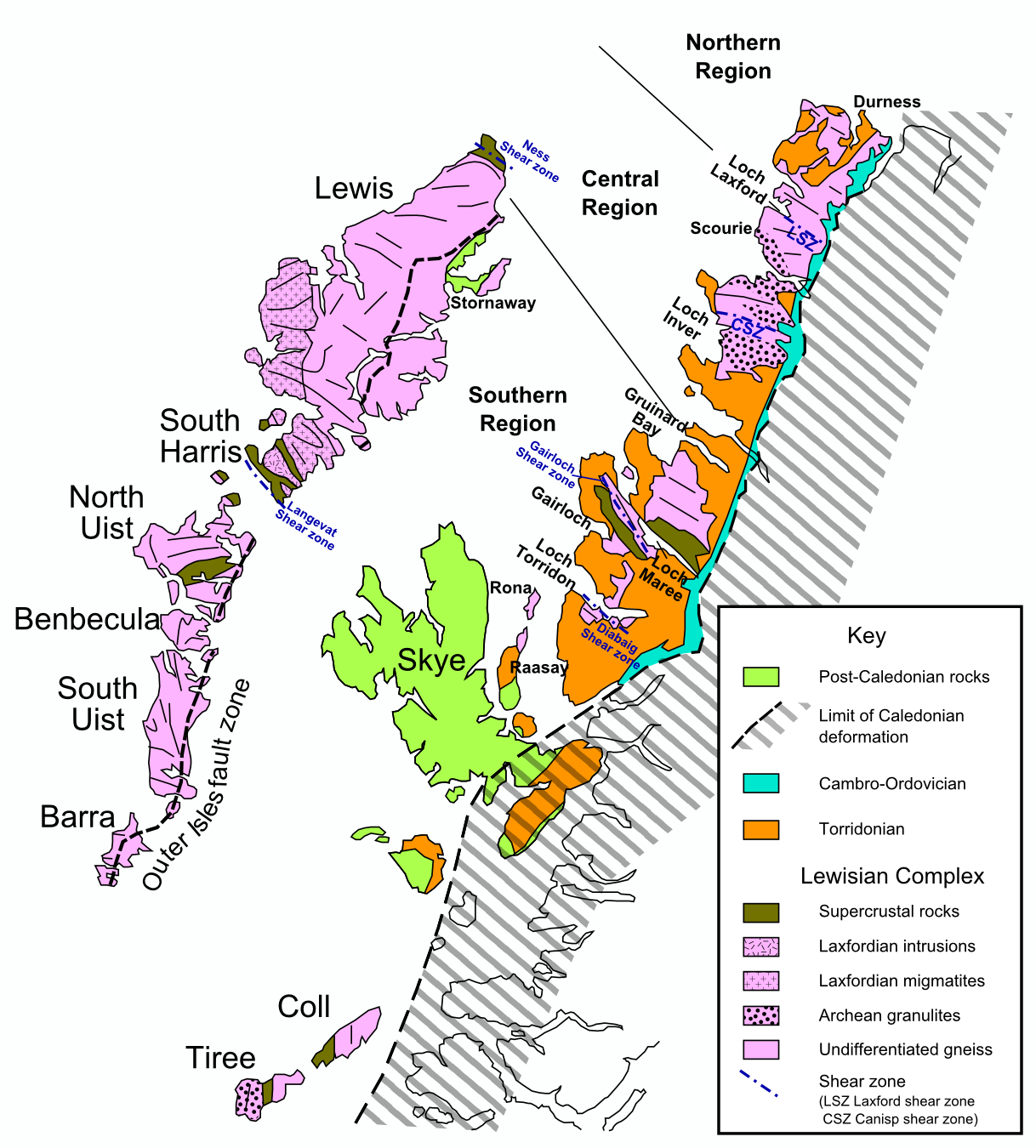

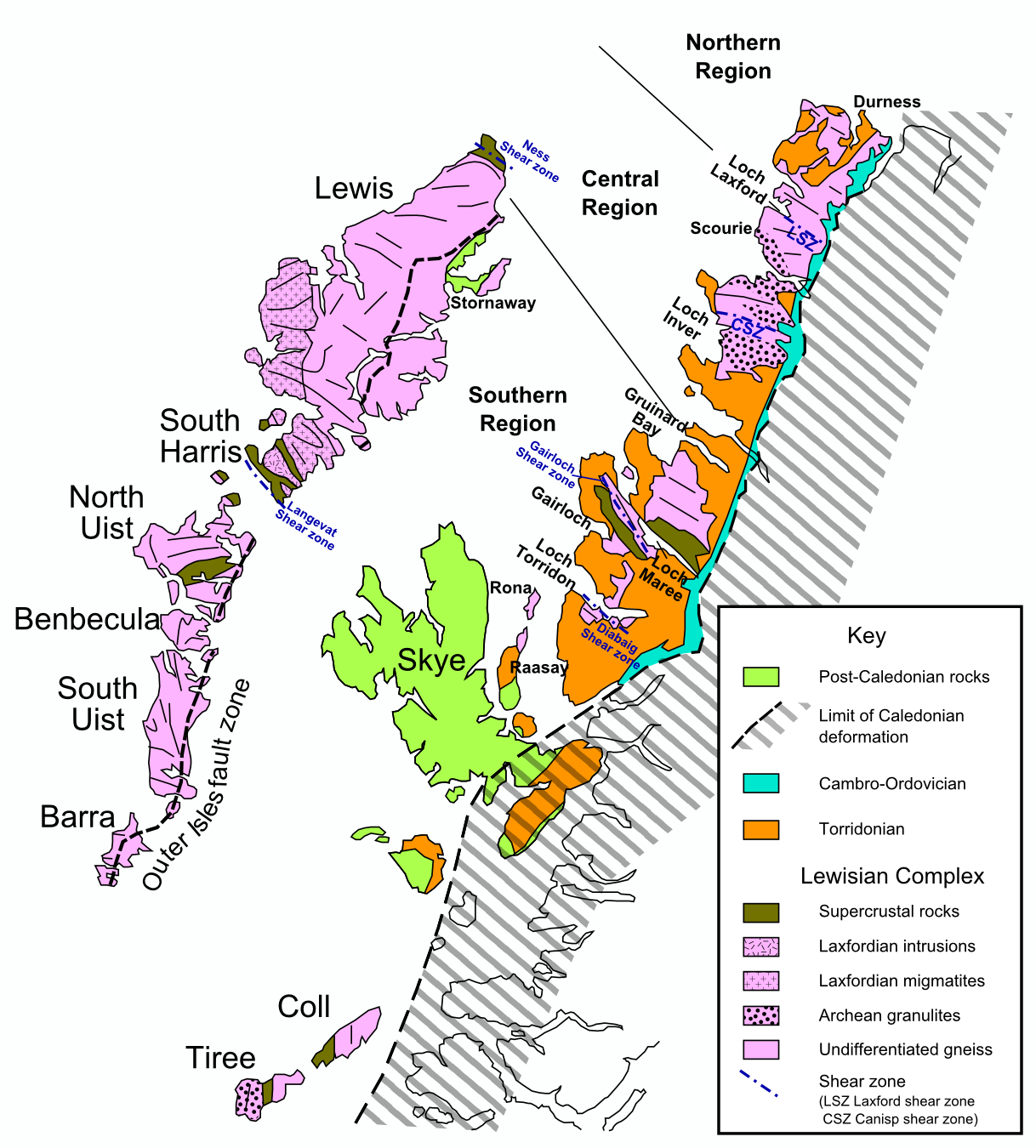

, the term Torridonian is the informal name for the Torridonian Group, a series of Mesoproterozoic

The Mesoproterozoic Era is a geologic era that occurred from . The Mesoproterozoic was the first era of Earth's history for which a fairly definitive geological record survives. Continents existed during the preceding era (the Paleoproterozoic), ...

to Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

arenaceous

Arenite ( Latin: ''arena'', "sand") is a sedimentary clastic rock with sand grain size between 0.0625 mm (0.00246 in) and 2 mm (0.08 in) and contain less than 15% matrix. The related adjective is ''arenaceous''. The equivalen ...

and argillaceous

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

Clay minerals ...

sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

s, which occur extensively in the Northwest Highlands

The Northwest Highlands are located in the northern third of Scotland that is separated from the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen (Glen More). The region comprises Wester Ross, Assynt, Sutherland and part of Caithness. The Caledonian Canal, ...

of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. The strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

of the Torridonian Group are particularly well exposed in the district of upper Loch Torridon

Loch Torridon ( gd, Loch Thoirbheartan) is a sea loch on the west coast of Scotland in the Northwest Highlands. The loch was created by glacial processes and is in total around 15 miles (25 km) long. It has two sections: Upper Loch Torridon ...

, a circumstance which suggested the name Torridon Sandstone, first applied to these rocks by James Nicol. Stratigraphically, they lie unconformably

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

on gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

es of the Lewisian complex

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Pale ...

and their outcrop

An outcrop or rocky outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth.

Features

Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most places the bedrock or superficia ...

extent is restricted to the Hebridean Terrane.

Rock type

The rocks are mainly red and brownsandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

s, arkose

Arkose () or arkosic sandstone is a detrital sedimentary rock, specifically a type of sandstone containing at least 25% feldspar.

Arkosic sand is sand that is similarly rich in feldspar, and thus the potential precursor of arkose.

Quartz is c ...

s and shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especiall ...

s with coarse conglomerate

Conglomerate or conglomeration may refer to:

* Conglomerate (company)

* Conglomerate (geology)

* Conglomerate (mathematics)

In popular culture:

* The Conglomerate (American group), a production crew and musical group founded by Busta Rhymes

** ...

s locally at the base. Some of the materials of these rocks were derived from the underlying Lewisian gneiss

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Pale ...

, upon the uneven surface of which they rest, but the bulk of the material was obtained from rocks that are nowhere now exposed. Upon this ancient denuded

Denudation is the geological processes in which moving water, ice, wind, and waves erode the Earth's surface, leading to a reduction in elevation and in relief of landforms and landscapes. Although the terms erosion and denudation are used interc ...

land surface the Torridonian strata rest horizontally or with gentle inclination

Orbital inclination measures the tilt of an object's orbit around a celestial body. It is expressed as the angle between a reference plane and the orbital plane or axis of direction of the orbiting object.

For a satellite orbiting the Ea ...

. Some of the peaks, such as Beinn Eighe

Beinn Eighe () is a mountain massif in the Torridon area of Wester Ross in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. Lying south of Loch Maree, it forms a long ridge with many spurs and summits, two of which are classified as Munros: Rua ...

, are capped with white Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ...

quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tec ...

, giving them a distinctive appearance when seen from afar. Some of the quartzite contains fossilized worm burrows and is known as ''pipe rock''. It is circa 500 million years old. The Torridon landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

is itself highly denuded by glacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

and alluvial

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. ...

action, and represents the remnants of an ancient peneplain

390px, Sketch of a hypothetical peneplain formation after an orogeny.

In geomorphology and geology, a peneplain is a low-relief plain formed by protracted erosion. This is the definition in the broadest of terms, albeit with frequency the usage ...

.

Occurrence

Their outcrop extends in a belt of variable breadth from

Their outcrop extends in a belt of variable breadth from Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath ( gd, Am Parbh, known as ' in Lewis) is a cape in the Durness parish of the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the most north-westerly point in mainland Britain.

The cape is separated from the rest of the ma ...

to the Point of the peninsula of Sleat in Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated ...

, running in a N.N.E.-S.S.W. direction through Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded ...

, Sutherland

Sutherland ( gd, Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. Its county town is Dornoch. Sutherland borders Caithness and Moray Firth to the east, Ross-shire and Cromartyshire (later c ...

, Ross and Cromarty

Ross and Cromarty ( gd, Ros agus Cromba), sometimes referred to as Ross-shire and Cromartyshire, is a variously defined area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. There is a registration county and a lieutenancy area in current use, the lat ...

, and Skye and Lochalsh

Skye and Lochalsh ( gd, 'An t-Eilean Sgitheanach agus Loch Aillse') is one of eight former local government districts of the two-tier Highland region of Scotland. The main offices of the Skye and Lochalsh district council were in Portree, on the ...

. They form the isolated mountain peaks of Canisp

Canisp (Scottish Gaelic: ''Canasp'') is a mountain in the far north west of Scotland. It is situated in the parish of Assynt, in the county of Sutherland, north of the town of Ullapool. Canisp reaches a height of and qualifies as a Corbett an ...

, Quinag

Quinag ( gd, A’ Chuineag) is an 808 m high mountain range in Sutherland in the Scottish Highlands, with an undulating series of peaks along its Y-shaped crest. The name Quinag is an anglicisation of the Gaelic name ''Cuinneag'', a milk pail ...

and Suilven

Suilven ( gd, Sùilebheinn) is a mountain in Scotland. Lying in a remote area in the west of Sutherland, it rises from a wilderness landscape of moorland, bogs, and lochans known as Inverpolly National Nature Reserve. Suilven forms a steep- ...

in the area of Loch Assynt

Loch Assynt ( gd, Loch Asaint) is a freshwater loch in Sutherland, Scotland, east-north east of Lochinver.

Situated in a spectacular setting between the heights of Canisp, Quinag and Beinn Uidhe, it receives the outflow from Lochs Awe, Maol ...

, of Slioch

, photo = Slioch_from_Loch_Maree.jpg

, photo_caption = Slioch seen from the shores of Loch Maree.

, elevation_m = 981

, elevation_ref =

, prominence_m = 626

, prominence_ref =

, parent_peak = Sgurr Mor

, listing = Munro, Marilyn

, tr ...

near Loch Maree

Loch Maree ( gd, Loch Ma-ruibhe) is a loch in Wester Ross in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. At long and with a maximum width of , it is the fourth-largest freshwater loch in Scotland; it is the largest north of Loch Ness. Its surface a ...

, and other hills. They attain their maximum development in the Applecross

Applecross ( gd, A' Chomraich) is a peninsula north-west of Kyle of Lochalsh in the council area of Highland, Scotland. The name Applecross is at least 1,300 years old and is ''not'' used locally to refer to the 19th century village (which is ...

, Gairloch

Gairloch ( ; gd, Geàrrloch , meaning "Short Loch") is a village, civil parish and community on the shores of Loch Gairloch in Wester Ross, in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. A tourist destination in the summer months, Gairloch has a go ...

and Torridon

Torridon (Scottish Gaelic: ''Toirbheartan'') is a small village in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. However the name is also applied to the area surrounding the village, particularly the Torridon Hills, mountains to the north of Glen Torrido ...

districts, form the greater part of Scalpay, and occur also in Rùm

Rùm (), a Scottish Gaelic name often anglicised to Rum (), is one of the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides, in the district of Lochaber, Scotland. For much of the 20th century the name became Rhum, a spelling invented by the former owner, Sir ...

, Raasay

Raasay (; gd, Ratharsair) or the Isle of Raasay is an island between the Isle of Skye and the mainland of Scotland. It is separated from Skye by the Sound of Raasay and from Applecross by the Inner Sound. It is famous for being the birt ...

, Soay and the Crowlin Islands. They are also found beneath much of the Sea of the Hebrides

The Sea of the Hebrides ( gd, An Cuan Barrach, ) is a small, partly sheltered section of the North Atlantic Ocean, indirectly off the southern part of the north-west coast of Scotland. To the east are the mainland of Scotland and the northern ...

overlying the Lewisian gneiss.C.Michael Hogan, (2011''Sea of the Hebrides''

Eds. P. Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC.

Sub-divisions

The Torridonian is divided into the older Stoer Group and the younger Sleat and Torridon Groups separated by an angular unconformity. Paleomagnetic data suggest that this unconformity represents a major time break. These sediments are interpreted to have been deposited during a period ofrift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ing.

Stoer Group

The Stoer Group outcrops on the peninsula of Stoer, nearAssynt

Assynt ( gd, Asainn or ) is a sparsely populated area in the south-west of Sutherland, lying north of Ullapool on the west coast of Scotland. Assynt is known for its landscape and its remarkable mountains, which have led to the area, along with ...

, Sutherland

Sutherland ( gd, Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. Its county town is Dornoch. Sutherland borders Caithness and Moray Firth to the east, Ross-shire and Cromartyshire (later c ...

. It is subdivided into three formations.

Clachtoll Formation

A basalbreccia

Breccia () is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or rocks cemented together by a fine-grained matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language, in which it means "rubble". A breccia may have a variety of ...

is present in many areas with large clasts derived from the underlying Lewisian. There is local evidence of weathering of the gneiss beneath the unconformity. Away from the unconformity the breccia becomes crudely stratified within an overall fining upwards sequence passing up into pebbly sandstones, the deposits of small alluvial fans. This breccia facies passes vertically and laterally in most places into muddy massive sandstones, true greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke (German ''grauwacke'', signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lit ...

s. The lower part of these sandstones are almost unbedded being replaced upwards by half metre thick beds capped by siltstones often with well-preserved desiccation structures. In parts of the outcrop, the muddy sandstones are succeeded by the deposits of a braided river

A braided river, or braided channel, consists of a network of river channels separated by small, often temporary, islands called braid bars or, in English usage, ''aits'' or ''eyots''.

Braided streams tend to occur in rivers with high sediment ...

system, trough cross-bedded sandstones and conglomerates.

Bay of Stoer Formation

The Bay of Stoer Formation consists of a lower section formed of red trough cross-bedded sandstones with some pebbles, interpreted to be the deposits of a braided river system. The uppermost 100 m of the formation, the Stac Fada and Poll a' Mhuilt members, form a distinctive marker layer within the Stoer Group succession with a strike extent of 50 km. TheStac Fada Member

The Stac Fada Member is a distinctive layer towards the top of the Mesoproterozoic Bay of Stoer Formation, part of the Stoer Group (lowermost Torridonian Supergroup) in northwest Scotland. This rock unit is generally thick and is made of sandsto ...

is generally about 10 m thick and consists of muddy sandstone facies

In geology, a facies ( , ; same pronunciation and spelling in the plural) is a body of rock with specified characteristics, which can be any observable attribute of rocks (such as their overall appearance, composition, or condition of formatio ...

with abundant clasts of vesicular volcanic glass

Volcanic glass is the amorphous (uncrystallized) product of rapidly cooling magma. Like all types of glass, it is a state of matter intermediate between the closely packed, highly ordered array of a crystal and the highly disordered array of ...

, locally with accretionary lapilli

Lapilli is a size classification of tephra, which is material that falls out of the air during a volcanic eruption or during some meteorite impacts. ''Lapilli'' (singular: ''lapillus'') is Latin for "little stones".

By definition lapilli range ...

. The matrix for these volcanic clasts is always non-volcanic suggesting transport from the area where they were erupted. The member also includes large rafts of gneiss and sandstone, up to 15 m in length. The Stac Fada member has been traditionally interpreted to be a mudflow. An alternative suggestion has been that the member represents part of the proximal ejecta blanket from an impact crater

An impact crater is a circular depression in the surface of a solid astronomical object formed by the hypervelocity impact of a smaller object. In contrast to volcanic craters, which result from explosion or internal collapse, impact crater ...

. This interpretation is supported by the presence of shocked quartz and biotite

Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron- endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more ...

. The overlying Poll a' Mhuilt member consists of a thin sequence of siltstones and fine sandstones alternating with muddy sandstones, suggesting deposition in a lacustrine

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much larger ...

environment.

Meall Dearg Formation

The uppermost part of the sequence consists of trough cross-bedded sandstones thought to have been deposited by braided rivers, similar to the lower part of the Bay of Stoer Formation, possibly with wider channels and a lower paleoslope.Sleat Group

The Sleat Group, which outcrops on the Sleat peninsula onSkye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated ...

, underlies the Torridon Group conformably, but the relationship with the Stoer Group is nowhere exposed. It is presumed to have been deposited later than the Stoer Group, but possibly in a separate sub-basin. It is metamorphosed to greenschist facies

Greenschists are metamorphic rocks that formed under the lowest temperatures and pressures usually produced by regional metamorphism, typically and 2–10 kilobars (). Greenschists commonly have an abundance of green minerals such as chlorite, ...

and sits within the Kishorn Nappe, part of the Caledonian thrust belt, making its exact relationship to the other outcrops difficult to assess. The sequence consists of mainly coarse feldspathic sandstones deposited in a fluvial environment with some less common grey shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especiall ...

s, probably deposited in a lacustrine environment.

Rubha Guail Formation

Theunconformity

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

at the base of the Sleat Group is not exposed on Skye, but at Kyle of Lochalsh

Kyle of Lochalsh (from the Gaelic ''Caol Loch Aillse'', "strait of the foaming loch") is a village in the historic county of Ross-shire on the northwest coast of Scotland, located around west-southwest of Inverness. It is located on the L ...

, the basal part of the sequence is seen to consist of breccias, with clasts derived from the underlying gneiss. Topographic relief

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin w ...

on the unconformity reaches several hundred metres.

Most of the remaining part of the formation consists of coarse green trough cross-bedded sandstones, the colour coming from its content of epidote

Epidote is a calcium aluminium iron sorosilicate mineral.

Description

Well developed crystals of epidote, Ca2Al2(Fe3+;Al)(SiO4)(Si2O7)O(OH), crystallizing in the monoclinic system, are of frequent occurrence: they are commonly prismatic in ...

and chlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorou ...

. The coarse sandstone beds are interbedded with fine-grained sandstones and siltstones, which become more common towards the top of the formation. The siltstones show desiccation features. The formation shows an overall upward-fining trend, which continued with the overlying Loch na Dal Formation siltstones.

Loch na Dal Formation

The basal part of this formation is formed of laminated dark-grey siltstones. This 200 m thick unit is oftenphosphatic

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

and contains occasional coarse to very coarse sandstone laminae. It is interpreted to represent the maximum expansion of a lake. The upper part of the formation is composed mainly of coarse, occasionally pebbly, trough cross-bedded sandstones, interpreted to record the building out of a series of deltas into the earlier lake.

Beinn na Seamraig Formation

This formation consist of coarse-grained cross-bedded sandstones, typically showing contorted bedding.Kinloch Formation

This formation is similar to the underlying Beinn na Seamraig Formation. The main difference is that the sandstones are generally finer-grained than those below and have better developed ripple-drift lamination. The sediments show marked cyclicity, with fining upward cycles, 25–35 m thick, with shales developed at the top. The uppermost boundary of this group with the overlying Torridon Group has been interpreted to be conformable, with evidence of interfingering between the Kinloch Formation shales and Applecross Formation sandstones. In support of this observation, there are no sandstone clasts above the boundary and no change in magnetisation between the formations. The main difference is in the degree of albitisation of the feldspars; those in the Sleat Group are only partially affected, while those in the Applecross Formation are completely albitised. There is also some evidence for a change in bedding orientation across the boundary, which is nowhere well-exposed, suggesting that it may represent some sort of disconformity.Torridon Group

The Torridon Group infills an irregular land surface with up to 600 m of topography locally, cutting down through the previously deposited Stoer group sediments, resting in many areas directly on the Lewisian. It has been suggested that there is significant unconformity within this group, between the Diabaig and Applecross Formations.

The Torridon Group infills an irregular land surface with up to 600 m of topography locally, cutting down through the previously deposited Stoer group sediments, resting in many areas directly on the Lewisian. It has been suggested that there is significant unconformity within this group, between the Diabaig and Applecross Formations.

Diabaig Formation

The lowest part of this formation consists of a basal breccia containing clasts derived from the underlying Lewisian complex with the thickest developments in the paleovalleys. The breccias passing vertically and laterally into tabular sandstones. These are locally channelised and interfinger with grey shales containing thin beds of fine-grained sandstone with wave rippled surfaces. The shales show the effects of desiccation with mudcracks preserved by being filled by overlying sandstone layers. In the upper part of the formation, beds of massive sandstone with sharp bases appear, becoming more common and thicker bedded towards the top. Ripple-drift lamination at the top of the sandstone layers indicates deposition from easterly-flowing currents. This sequence is interpreted to be to represent the progressive infill of the topography byalluvial fan

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to semiarid climates, but a ...

s building out into ephemeral lakes. The more massive beds are interpreted to be lake turbidite

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Sequencing

Turbidites wer ...

s.

Applecross Formation

This formation consists of coarse sandstones, both trough and planar cross-bedded. The orientation of the troughs suggest a paleocurrent flowing from the Northwest. The sandstones carry a distinctive set of pebbles, includingjasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases,Kostov, R. I. 2010. Review on the mineralogical systematics of jasper and related rocks. – Archaeometry Workshop, 7, 3, 209-213PDF/ref ...

and porphyry. Most of the sandstone beds are affected by soft-sediment deformation structures suggesting liquefaction

In materials science, liquefaction is a process that generates a liquid from a solid or a gas or that generates a non-liquid phase which behaves in accordance with fluid dynamics.

It occurs both naturally and artificially. As an example of th ...

, possibly as a result of seismic activity

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

. The uppermost part of the formation consists of finer-grained sandstones, transitional to those of the overlying Aultbea Formation. At Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath ( gd, Am Parbh, known as ' in Lewis) is a cape in the Durness parish of the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the most north-westerly point in mainland Britain.

The cape is separated from the rest of the ma ...

the basal part of the formation shows a fanning of paleocurrent directions consistent with deposition from a large alluvial fan (~40 km radius) with its apex near the Minch Fault. The source area for this fan has been calculated as about 10,000 km2.

Aultbea Formation

This formation is similar to the Applecross formation except that the sandstones are fine to medium-grained and there are very few pebbles. Almost all of these sandstone beds show the contortions shown by the older formation.

The Applecross and Aultbea Formations together consist of an overall fining-upward sequence of sandstones. Only the outcrops at

This formation is similar to the Applecross formation except that the sandstones are fine to medium-grained and there are very few pebbles. Almost all of these sandstone beds show the contortions shown by the older formation.

The Applecross and Aultbea Formations together consist of an overall fining-upward sequence of sandstones. Only the outcrops at Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath ( gd, Am Parbh, known as ' in Lewis) is a cape in the Durness parish of the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the most north-westerly point in mainland Britain.

The cape is separated from the rest of the ma ...

described above have a consistent radial pattern suggesting that the sequence was deposited in a bajada environment, by a series of smaller fans merging to form a braided river system.

Cailleach Head Formation

This formation is similar to the underlying Aultbea Formation, the main difference being in grain size, with this formation being noticeably finer-grained. The sequence is made up of 22 m thick cycles, each with a basalerosion surface

In geology and geomorphology, an erosion surface is a surface of rock (geology), rock or regolith that was formed by erosion and not by construction (e.g. lava flows, sediment deposition) nor fault (geology), fault displacement. Erosional surfaces ...

followed by dark grey shales with desiccation cracks, planar cross-bedded sandstones with wave rippled tops, overlain by trough cross-bedded mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

ceous sandstones. These cycles are thought to represent repeated progradation of deltas into a lake. A lack of evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as ocean ...

minerals suggest that the lakes had through drainage. Acritarch

Acritarchs are organic microfossils, known from approximately 1800 million years ago to the present. The classification is a catch all term used to refer to any organic microfossils that cannot be assigned to other groups. Their diversity refle ...

microfossils

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

were described from here by Teall in 1907, the first Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

fossils described in Britain.

Age

The upper age limit for the deposition of this sequence is constrained by the age of the last tectonic and metamorphic event to affect the Lewisian complex on which it was deposited, for which ages cluster between about 1200–1100 Ma. The lower limit is provided by the age of the lower Cambrian quartzite that lies above it, about 544 Ma. Radiometric ages from the Torridonian sequence itself give ages of about 1200 Ma for the Stoer Group and 1000–950 for the basal part of the Torridon Group. This implies an age gap of at least 200 Ma between the deposition of these two groups, consistent with the paleomagnetic evidence. Ages of detritalzircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

s also provide some constraints on the sequence age. The Stoer group and the lower part of the Sleat Group show ages consistent with derivation from Scourian and to a lesser extent Laxfordian rocks, with no dates after 1700 Ma. The upper part of the Sleat Group includes a large component of broadly Laxfordian age with almost no Archaean ages, with a lower limit of about 1200 Ma. In contrast the Diabaig Formation shows a small group clustered around 1100 Ma, the age of the Grenville Orogeny

The Grenville orogeny was a long-lived Mesoproterozoic mountain-building event associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia. Its record is a prominent orogenic belt which spans a significant portion of the North American continent, f ...

. In the Applecross and Aultbea Formations there are many more zircons giving ages around 1100 Ma and even below 1000 Ma. This evidence suggest that the Stour and Sleat Groups were deposited before the Grenvillian event, pre-1200 Ma, while the Diabaig Formation was deposited after the orogeny, after about 1090 Ma, and the remaining parts of the Torridon Group after about 1060 Ma. A more precise age has been obtained for authigenic

Authigenesis is the process whereby a mineral or sedimentary rock deposit is generated where it is found or observed. Such deposits are described as authigenic. Authigenic sedimentary minerals form during sedimentation by precipitation or rec ...

feldspars in the Stac Fada Member of the Stoer Group at 1177±5 Ma interpreted to have formed immediately after emplacement of the ejecta blanket.

Tectonic setting

Variations in thickness andlithology

The lithology of a rock unit is a description of its physical characteristics visible at outcrop, in hand or core samples, or with low magnification microscopy. Physical characteristics include colour, texture, grain size, and composition. Li ...

are consistent with both the Stoer and Sleat/Torridon Groups being deposited in a rift setting. Evidence from seismic reflection data in the Minch

The Minch ( gd, An Cuan Sgitheanach, ', ', '), also called North Minch, is a strait in north-west Scotland, separating the north-west Highlands and the northern Inner Hebrides from Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides. It was known as ("S ...

suggests that the Minch Fault was active throughout the deposition of the Torridon Group. This is consistent with the generally westerly derived pebbly material throughout the thickness of the Applecross Formation, suggesting a constantly rejuvenated sediment source in that direction. More recent work has suggested that although the Stoer and Sleat Groups were probably deposited in a rift setting, the scale and continuity of the Torridon Group, particularly the Applecross and Aultbea Formations, is more consistent with a molasse

__NOTOC__

The term "molasse" () refers to sandstones, shales and conglomerates that form as terrestrial or shallow marine deposits in front of rising mountain chains. The molasse deposits accumulate in a foreland basin, especially on top of flysc ...

type setting possibly related to the Grenville Orogeny

The Grenville orogeny was a long-lived Mesoproterozoic mountain-building event associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia. Its record is a prominent orogenic belt which spans a significant portion of the North American continent, f ...

.

References

{{commons category Sandstone in the United Kingdom Geology of Scotland Caithness Sutherland Ross and Cromarty Skye and Lochalsh Stratigraphy of the United Kingdom Torridon