Timeline of meteorology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The timeline of meteorology contains events of scientific and technological advancements in the area of atmospheric sciences. The most notable advancements in observational

* 1607 –

* 1607 –

FAQ: Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Tropical Cyclones: Hurricane TimelineHurricane Research Division, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, NOAA

''January 2006''.

* 1761 –

Publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved on November 6, 2013. * 1777 –

meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the conditions of the atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia and formally since the 19th cent ...

, climatology

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''-logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of study ...

, atmospheric chemistry

Atmospheric chemistry is a branch of atmospheric science in which the chemistry of the Earth's atmosphere and that of other planets is studied. It is a multidisciplinary approach of research and draws on environmental chemistry, physics, meteorol ...

, and atmospheric physics

Within the atmospheric sciences, atmospheric physics is the application of physics to the study of the atmosphere. Atmospheric physicists attempt to model Earth's atmosphere and the atmospheres of the other planets using fluid flow equations, chem ...

are listed chronologically. Some historical weather events are included that mark time periods where advancements were made, or even that sparked policy change.

Antiquity

* 3000 BC – Meteorology in India can be traced back to around 3000 BC, with writings such as theUpanishads

The Upanishads (; sa, उपनिषद् ) are late Vedic Sanskrit texts that supplied the basis of later Hindu philosophy.Wendy Doniger (1990), ''Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism'', 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, , ...

, containing discussions about the processes of cloud formation and rain and the seasonal cycles caused by the movement of earth round the sun.

* 600 BC – Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

may qualify as the first Greek meteorologist. He reputedly issues the first seasonal crop forecast.

* 400 BC – There is some evidence that Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

predicted changes in the weather, and that he used this ability to convince people that he could predict other future events.

* 400 BC – Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

writes a treatise called ''Airs, Waters and Places'', the earliest known work to include a discussion of weather. More generally, he wrote about common diseases that occur in particular locations, seasons, winds and air.

* 350 BC – The Greek philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

writes ''Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

'', a work which represents the sum of knowledge of the time about earth sciences, including weather and climate. It is the first known work that attempts to treat a broad range of meteorological topics. For the first time, precipitation and the clouds from which precipitation falls are called meteors, which originate from the Greek word ''meteoros'', meaning 'high in the sky'. From that word comes the modern term meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, the study of clouds and weather.

:Although the term ''meteorology'' is used today to describe a subdiscipline of the atmospheric sciences, Aristotle's work is more general. Meteorologica is based on intuition and simple observation, but not on what is now considered the scientific method. In his own words:

::''...all the affections we may call common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the earth and the affections of its parts.''

::The magazine '' De Mundo'' (attributed to Pseudo-Aristotle Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their work to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known as ps ...

) notes:

::''Cloud is a vaporous mass, concentrated and producing water. Rain is produced from the compression of a closely condensed cloud, varying according to the pressure exerted on the cloud; when the pressure is slight it scatters gentle drops; when it is great it produces a more violent fall, and we call this a shower, being heavier than ordinary rain, and forming continuous masses of water falling over earth. Snow is produced by the breaking up of condensed clouds, the cleavage taking place before the change into water; it is the process of cleavage which causes its resemblance to foam and its intense whiteness, while the cause of its coldness is the congelation of the moisture in it before it is dispersed or rarefied. When snow is violent and falls heavily we call it a blizzard. Hail is produced when snow becomes densified and acquires impetus for a swifter fall from its close mass; the weight becomes greater and the fall more violent in proportion to the size of the broken fragments of cloud. Such then are the phenomena which occur as the result of moist exhalation.''

:One of the most impressive achievements in ''Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

'' is his description of what is now known as the hydrologic cycle

The water cycle, also known as the hydrologic cycle or the hydrological cycle, is a biogeochemical cycle that describes the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth. The mass of water on Earth remains fairly const ...

:

::''Now the sun, moving as it does, sets up processes of change and becoming and decay, and by its agency the finest and sweetest water is every day carried up and is dissolved into vapour and rises to the upper region, where it is condensed again by the cold and so returns to the earth.''

*Several years after Aristotle's book, his pupil Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

puts together a book on weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the conditions of the atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia and formally since the 19th cent ...

called ''The Book of Signs''. Various indicators such as solar and lunar halos formed by high clouds are presented as ways to forecast the weather. The combined works of Aristotle and Theophrastus have such authority they become the main influence in the study of clouds, weather and weather forecasting for nearly 2000 years.

* 250 BC – Archimedes studies the concepts of buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the ...

and the hydrostatic principle. Positive buoyancy is necessary for the formation of convective clouds (cumulus

Cumulus clouds are clouds which have flat bases and are often described as "puffy", "cotton-like" or "fluffy" in appearance. Their name derives from the Latin ''cumulo-'', meaning ''heap'' or ''pile''. Cumulus clouds are low-level clouds, gener ...

, cumulus congestus

Cumulus congestus clouds, also known as towering cumulus, are a form of cumulus that can be based in the low or middle height ranges. They achieve considerable vertical development in areas of deep, moist convection. They are an intermediate stage ...

and cumulonimbus

Cumulonimbus (from Latin ''cumulus'', "heaped" and ''nimbus'', "rainstorm") is a dense, towering vertical cloud, typically forming from water vapor condensing in the lower troposphere that builds upward carried by powerful buoyant air currents. ...

).

* 25 AD – Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

, a geographer for the Roman empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, formalizes the climatic zone system.

* c. 80 AD – In his ''Lunheng

The ''Lunheng'', also known by numerous English translations, is a wide-ranging Chinese classic text by Wang Chong (27- ). First published in 80, it contains critical essays on natural science and Chinese mythology, philosophy, and literature ...

'' (論衡; Critical Essays), the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

Chinese philosopher Wang Chong

Wang Chong (; 27 – c. 97 AD), courtesy name Zhongren (仲任), was a Chinese astronomer, meteorologist, naturalist, philosopher, and writer active during the Han Dynasty. He developed a rational, secular, naturalistic and mechanistic account ...

(27–97 AD) dispels the Chinese myth of rain coming from the heavens, and states that rain is evaporated from water on the earth into the air and forms clouds, stating that clouds condense into rain and also form dew, and says when the clothes of people in high mountains are moistened, this is because of the air-suspended rain water.Needham, Joseph (1986). '' Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth''. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. However, Wang Chong supports his theory by quoting a similar one of Gongyang Gao's, the latter's commentary on the ''Spring and Autumn Annals

The ''Spring and Autumn Annals'' () is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The ''Annals'' is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 241-year period from 722 to 48 ...

'', the Gongyang Zhuan

The ''Gongyang Zhuan'' (), also known as the ''Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals'' or the ''Commentary of Gongyang'', is a commentary on the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', and is thus one of the Chinese classics. Along with the '' ...

, compiled in the 2nd century BC, showing that the Chinese conception of rain evaporating and rising to form clouds goes back much farther than Wang Chong. Wang Chong wrote:

::''As to this coming of rain from the mountains, some hold that the clouds carry the rain with them, dispersing as it is precipitated (and they are right). Clouds and rain are really the same thing. Water evaporating upwards becomes clouds, which condense into rain, or still further into dew.''

Middle Ages

* 500 AD – In around 500 AD, the Indian astronomer, mathematician, and astrologer:Varāhamihira

Varāhamihira ( 505 – 587), also called Varāha or Mihira, was an ancient Indian astrologer, astronomer, and polymath who lived in Ujjain (Madhya Pradesh, India). He was born at Kapitba in a Brahmin family, in the Avanti region, roughly co ...

published his work Brihat-Samhita's, which provides clear evidence that a deep knowledge of atmospheric processes existed in the Indian region.

* 7th century – The poet Kalidasa in his epic Meghaduta, mentions the date of onset of the south-west Monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

over central India and traces the path of the monsoon clouds.

* 7th century – St. Isidore of Seville,in his work ''De Rerum Natura'', writes about astronomy, cosmology and meteorology. In the chapter dedicated to Meteorology, he discusses the thunder

Thunder is the sound caused by lightning. Depending upon the distance from and nature of the lightning, it can range from a long, low rumble to a sudden, loud crack. The sudden increase in temperature and hence pressure caused by the lightning pr ...

, clouds, rainbows

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows ca ...

and wind.

* 9th century – Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(Alkindus), an Arab naturalist, writes a treatise on meteorology entitled ''Risala fi l-Illa al-Failali l-Madd wa l-Fazr'' (''Treatise on the Efficient Cause of the Flow and Ebb''), in which he presents an argument on tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s which "depends on the changes which take place in bodies owing to the rise and fall of temperature."

* 9th century – Al-Dinawari

Abū Ḥanīfa Aḥmad ibn Dāwūd Dīnawarī ( fa, ابوحنيفه دينوری; died 895) was a Persian Islamic Golden Age polymath, astronomer, agriculturist, botanist, metallurgist, geographer, mathematician, and historian.

Life

Dina ...

, a Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

naturalist, writes the ''Kitab al-Nabat'' (''Book of Plants''), in which he deals with the application of meteorology to agriculture during the Muslim Agricultural Revolution

The Arab Agricultural Revolution was the transformation in agriculture from the 8th to the 13th century in the Islamic region of the Old World. The agronomic literature of the time, with major books by Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī, d ...

. He describes the meteorological character of the sky, the planets and constellations, the Sun and Moon, the lunar phases indicating seasons and rain, the ''anwa'' ( heavenly bodies of rain), and atmospheric phenomena such as winds, thunder, lightning, snow, floods, valleys, rivers, lakes, wells and other sources of water.

* 10th century – Ibn Wahshiyya

( ar, ابن وحشية), died , was a Nabataean (Aramaic-speaking, rural Iraqi) agriculturalist, toxicologist, and alchemist born in Qussīn, near Kufa in Iraq. He is the author of the '' Nabataean Agriculture'' (), an influential Arabic work ...

's ''Nabatean Agriculture

''The Nabataean Agriculture'' (), also written ''The Nabatean Agriculture'', is a 10th-century text on agronomy by Ibn Wahshiyya (died ), from Qussīn in present-day Iraq. It contains information on plants and agriculture, as well as on magic ...

'' discusses the weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the conditions of the atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia and formally since the 19th cent ...

of atmospheric changes and signs from the planetary astral alterations; signs of rain based on observation of the lunar phases, nature of thunder and lightning, direction of sunrise, behaviour of certain plants and animals, and weather forecasts based on the movement of winds; pollenized air and winds; and formation of winds and vapour

In physics, a vapor (American English) or vapour (British English and Canadian English; see spelling differences) is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical temperature,R. H. Petrucci, W. S. Harwood, and F. G. Herr ...

s.

* 1021 – Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pri ...

(Alhazen) writes on the atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric refraction is the deviation of light or other electromagnetic wave from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere due to the variation in air density as a function of height. This refraction is due to the velocity of ligh ...

of light, the cause of morning and evening twilight

Twilight is light produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, when the Sun is below the horizon, which illuminates the lower atmosphere and the Earth's surface. The word twilight can also refer to the periods of time when this i ...

.Mahmoud Al Deek (November–December 2004). "Ibn Al-Haitham: Master of Optics, Mathematics, Physics and Medicine, ''Al Shindagah''. He endeavored by use of hyperbola

In mathematics, a hyperbola (; pl. hyperbolas or hyperbolae ; adj. hyperbolic ) is a type of smooth curve lying in a plane, defined by its geometric properties or by equations for which it is the solution set. A hyperbola has two pieces, ca ...

and geometric optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

to chart and formulate basic laws on atmospheric refraction.Sami Hamarneh (March 1972). Review of Hakim Mohammed Said, ''Ibn al-Haitham'', ''Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

'' 63 (1), p. 119. He provides the first correct definition of the twilight

Twilight is light produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, when the Sun is below the horizon, which illuminates the lower atmosphere and the Earth's surface. The word twilight can also refer to the periods of time when this i ...

, discusses atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric refraction is the deviation of light or other electromagnetic wave from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere due to the variation in air density as a function of height. This refraction is due to the velocity of ligh ...

, shows that the twilight is due to atmospheric refraction and only begins when the Sun is 19 degrees below the horizon, and uses a complex geometric demonstration to measure the height of the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing fo ...

as 52,000 ''passuum'' (49 miles), which is very close to the modern measurement of 50 miles.

* 1020s – Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pri ...

publishes his ''Risala fi l-Daw’'' (''Treatise on Light'') as a supplement to his ''Book of Optics''. He discusses the meteorology of the rainbow

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows c ...

, the density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

of the atmosphere, and various celestial

Celestial may refer to:

Science

* Objects or events seen in the sky and the following astronomical terms:

** Astronomical object, a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists in the observable universe

** Celes ...

phenomena, including the eclipse, twilight and moonlight.

* 1027 – Avicenna publishes '' The Book of Healing'', in which Part 2, Section 5, contains his essay on mineralogy and meteorology in six chapters: formation of mountains; the advantages of mountains in the formation of clouds; sources of water; origin of earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s; formation of mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s; and the diversity of earth's terrain

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin wo ...

. He also describes the structure of a meteor

A meteoroid () is a small rocky or metallic body in outer space.

Meteoroids are defined as objects significantly smaller than asteroids, ranging in size from grains to objects up to a meter wide. Objects smaller than this are classified as mi ...

, and his theory on the formation of metals combined the alchemical

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

sulfur-mercury theory of metals (although he was critical of alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

) with the mineralogical theories of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

. His scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

ology of field observation was also original in the Earth sciences.

* Late 11th century – Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ma'udh, who lived in Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, wrote a work on optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

later translated into Latin as ''Liber de crepisculis'', which was mistakenly attributed to Alhazen. This was a short work containing an estimation of the angle of depression of the sun at the beginning of the morning twilight

Twilight is light produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, when the Sun is below the horizon, which illuminates the lower atmosphere and the Earth's surface. The word twilight can also refer to the periods of time when this i ...

and at the end of the evening twilight, and an attempt to calculate on the basis of this and other data the height of the atmospheric moisture responsible for the refraction of the sun's rays. Through his experiments, he obtained the accurate value of 18°, which comes close to the modern value.

* 1088 – In his '' Dream Pool Essays'' (夢溪筆談), the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo wrote vivid descriptions of tornadoes

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, alth ...

, that rainbow

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows c ...

s were formed by the shadow of the sun in rain, occurring when the sun would shine upon it, and the curious common phenomena of the effect of lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an avera ...

that, when striking a house, would merely scorch the walls a bit but completely melt to liquid all metal objects inside.

* 1121 – Al-Khazini

Abū al-Fath Abd al-Rahman Mansūr al-Khāzini or simply al-Khāzini (, flourished 1115–1130) was an Iranian astronomer of Greek origin from Seljuk Persia. His astronomical tables written under the patronage of Sultan Sanjar (', 1115) is con ...

, a Muslim scientist of Byzantine Greek descent, publishes ''The Book of the Balance of Wisdom'', the first study on the hydrostatic balance

In fluid mechanics, hydrostatic equilibrium (hydrostatic balance, hydrostasy) is the condition of a fluid or plastic solid at rest, which occurs when external forces, such as gravity, are balanced by a pressure-gradient force. In the planetary ...

.

*13th century- St. Albert the Great is the first to propose that each drop of falling rain had the form of a small sphere, and that this form meant that the rainbow was produced by light interacting with each raindrop.Ancient and pre-Renaissance Contributors to MeteorologyNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (abbreviated as NOAA ) is an United States scientific and regulatory agency within the United States Department of Commerce that forecasts weather, monitors oceanic and atmospheric conditio ...

(NOAA)

* 1267 – Roger Bacon was the first to calculate the angular size of the rainbow. He stated that the rainbow summit can not appear higher than 42 degrees above the horizon.

* 1337 – William Merle, rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Driby, starts recording his weather diary, the oldest existing in print. The endeavour ended 1344.

* Late 13th century – Theodoric of Freiberg

Theodoric of Freiberg (; – ) was a German member of the Dominican order and a theologian and physicist. He was named provincial of the Dominican Order in 1293, Albert the Great's old post. He is considered one of the notable philosophers and th ...

and Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī

Kamal al-Din Hasan ibn Ali ibn Hasan al-Farisi or Abu Hasan Muhammad ibn Hasan (1267– 12 January 1319, long assumed to be 1320)) ( fa, كمالالدين فارسی) was a Persian Muslim scientist. He made two major contributions to scien ...

give the first accurate explanations of the primary rainbow

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows c ...

, simultaneously but independently. Theoderic also gives the explanation for the secondary rainbow.

* 1441 – King Sejongs son, Prince Munjong, invented the first standardized rain gauge

A rain gauge (also known as udometer, pluvia metior, pluviometer, ombrometer, and hyetometer) is an instrument used by meteorologists and hydrologists to gather and measure the amount of liquid precipitation over a predefined area, over a period o ...

. These were sent throughout the Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and r ...

of Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

as an official tool to assess land taxes based upon a farmer's potential harvest.

* 1450 – Leone Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

developed a swinging-plate anemometer

In meteorology, an anemometer () is a device that measures wind speed and direction. It is a common instrument used in weather stations. The earliest known description of an anemometer was by Italian architect and author Leon Battista Alberti ...

, and is known as the first ''anemometer''.

:: – Nicolas Cryfts, ( Nicolas of Cusa), described the first hair hygrometer

A hair tension dial hygrometer with a nonlinear scale.

A hygrometer is an instrument used to measure the amount of water vapor in air, in soil, or in confined spaces. Humidity measurement instruments usually rely on measurements of some other qu ...

to measure humidity. The design was drawn by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

, referencing Cryfts design in ''da Vinci's Codex Atlanticus

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a 12-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest single set. Its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was us ...

''.

* 1483 − Yuriy Drohobych

Yuriy Drohobych or Yuriy Kotermak, uk, Юрій Дрогобич, pl , Jerzy Drohobycz, Jerzy Kotermak Drusianus, Georgius Drohobicz, by birthname Yuriy Kotermak, Giorgio da Leopoli (1450 in Drohobych – 4 February 1494 in Kraków) was a Ukrai ...

publishes ''Prognostic Estimation of the year 1483'' in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he reflects upon weather forecasting and that climatic conditions depended on the latitude.

* 1488 – Johannes Lichtenberger publishes the first version of his ''Prognosticatio'' linking weather forecasting with astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

. The paradigm was only challenged centuries later.

* 1494 – During his second voyage Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

experiences a tropical cyclone in the Atlantic Ocean, which leads to the first written European account of a hurricane.

* 1510 – Leonhard Reynmann, astronomer of Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, publishes ″Wetterbüchlein Von warer erkanntnus des wetters″, a collection of weather lore

Weather lore is the body of informal folklore related to the prediction of the weather and its greater meaning.

Much like regular folklore, weather lore is passed down through speech and writing from normal people without the use of external me ...

.

* 1547 − Antonio Mizauld publishes "Le miroueer du temps, autrement dit, éphémérides perpétuelles de l'air par lesquelles sont tous les jours donez vrais signes de touts changements de temps, seulement par choses qui à tous apparoissent au cien, en l'air, sur terre & en l'eau. Le tout par petits aphorismes, & breves sentences diligemment compris" in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, with detail on forecasting weather, comets and earthquakes.

17th century

* 1607 –

* 1607 – Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

constructs a thermoscope

A thermoscope is a device that shows changes in temperature. A typical design is a tube in which a liquid rises and falls as the temperature changes. The modern thermometer gradually evolved from it with the addition of a scale in the early 17th c ...

. Not only did this device measure temperature, but it represented a paradigm shift. Up to this point, heat and cold were believed to be qualities of Aristotle's elements (fire, water, air, and earth). ''Note: There is some controversy about who actually built this first thermoscope. There is some evidence for this device being independently built at several different times.'' This is the era of the first recorded meteorological observations. As there was no standard measurement, they were of little use until the work of Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit FRS (; ; 24 May 1686 – 16 September 1736) was a physicist, inventor, and scientific instrument maker. Born in Poland to a family of German extraction, he later moved to the Dutch Republic at age 15, where he spen ...

and Anders Celsius

Anders Celsius (; 27 November 170125 April 1744) was a Swedish astronomer, physicist and mathematician. He was professor of astronomy at Uppsala University from 1730 to 1744, but traveled from 1732 to 1735 visiting notable observatories in Germ ...

in the 18th century.

* 1611 – Johannes Kepler writes the first scientific treatise on snow crystals: "Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula (A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow)".

* 1620 – Francis Bacon (philosopher)

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both n ...

analyzes the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

in his philosophical work; Novum Organum

The ''Novum Organum'', fully ''Novum Organum, sive Indicia Vera de Interpretatione Naturae'' ("New organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature") or ''Instaurationis Magnae, Pars II'' ("Part II of The Great Instauration ...

.

* 1643 – Evangelista Torricelli

Evangelista Torricelli ( , also , ; 15 October 160825 October 1647) was an Italian physicist and mathematician, and a student of Galileo. He is best known for his invention of the barometer, but is also known for his advances in optics and work ...

invents the mercury barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

.

* 1648 – Blaise Pascal rediscovers that atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, ...

decreases with height, and deduces that there is a vacuum above the atmosphere.

* 1654 – Ferdinando II de Medici sponsors the first ''weather observing'' network, that consisted of meteorological stations in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, Cutigliano

Cutigliano was a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Pistoia in the Italian region Tuscany, located about northwest of Florence and about northwest of Pistoia. It has been a frazione of Abetone Cutigliano

Abetone Cutigliano is a ''comun ...

, Vallombrosa, Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, music, art, prosciutto (ham), cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 inhabitants, Parma is the second mos ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, Innsbruck, Osnabrück

Osnabrück (; wep, Ossenbrügge; archaic ''Osnaburg'') is a city in the German state of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the river Hase in a valley penned between the Wiehen Hills and the northern tip of the Teutoburg Forest. With a population ...

, Paris and Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

. Collected data was centrally sent to Accademia del Cimento in Florence at regular time intervals.

* 1662 – Sir Christopher Wren invented the mechanical, self-emptying, tipping bucket rain gauge

A rain gauge (also known as udometer, pluvia metior, pluviometer, ombrometer, and hyetometer) is an instrument used by meteorologists and hydrologists to gather and measure the amount of liquid precipitation over a predefined area, over a period o ...

.

* 1667 – Robert Hooke builds another type of anemometer

In meteorology, an anemometer () is a device that measures wind speed and direction. It is a common instrument used in weather stations. The earliest known description of an anemometer was by Italian architect and author Leon Battista Alberti ...

, called a pressure-plate anemometer.

* 1686 – Edmund Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

presents a systematic study of the trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

s and monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

s and identifies solar heating as the cause of atmospheric motions.

:: – Edmund Halley establishes the relationship between barometric pressure and height above sea level.

18th century

* 1716 – Edmund Halley suggests thataurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

e are caused by "magnetic effluvia" moving along the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic ...

lines.

* 1724 – Gabriel Fahrenheit

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit FRS (; ; 24 May 1686 – 16 September 1736) was a physicist, inventor, and scientific instrument maker. Born in Poland to a family of German extraction, he later moved to the Dutch Republic at age 15, where he spent ...

creates reliable scale for measuring temperature with a mercury-type thermometer

A thermometer is a device that measures temperature or a temperature gradient (the degree of hotness or coldness of an object). A thermometer has two important elements: (1) a temperature sensor (e.g. the bulb of a mercury-in-glass thermometer ...

.

* 1735 – The first ''ideal'' explanation of global circulation was the study of the Trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisp ...

by George Hadley

George Hadley (12 February 1685 – 28 June 1768) was an English lawyer and amateur meteorologist who proposed the atmospheric mechanism by which the trade winds are sustained, which is now named in his honour as Hadley circulation. As a key ...

.

* 1738 – Daniel Bernoulli publishes ''Hydrodynamics'', initiating the kinetic theory of gases. He gave a poorly detailed equation of state

In physics, chemistry, and thermodynamics, an equation of state is a thermodynamic equation relating state variables, which describe the state of matter under a given set of physical conditions, such as pressure, volume, temperature, or intern ...

, but also the basic laws for the theory of gases.

* 1742 – Anders Celsius

Anders Celsius (; 27 November 170125 April 1744) was a Swedish astronomer, physicist and mathematician. He was professor of astronomy at Uppsala University from 1730 to 1744, but traveled from 1732 to 1735 visiting notable observatories in Germ ...

, a Swedish astronomer, proposed the Celsius temperature scale which led to the current Celsius scale.

* 1743 – Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

is prevented from seeing a lunar eclipse by a hurricane; he decides that cyclones move in a contrary manner to the winds at their periphery.Dorst, NealFAQ: Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Tropical Cyclones: Hurricane Timeline

''January 2006''.

Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

discovers that ice absorbs heat without changing its temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various Conversion of units of temperature, temp ...

when melting.

* 1772 – Black's student Daniel Rutherford

Daniel Rutherford (3 November 1749 – 15 December 1819) was a Scottish physician, chemist and botanist who is known for the isolation of nitrogen in 1772.

Life

Rutherford was born on 3 November 1749, the son of Anne Mackay and Professor John ...

discovers nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, which he calls ''phlogisticated air'', and together they explain the results in terms of the phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

.

* 1774 – Louis Cotte is put in charge of a "medico-meteorological" network of French veterinarians and country doctors to investigate the relationship between plague and weather. The project continued until 1794.

::- Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

begins twice daily observations compiled by Samuel Horsley

Samuel Horsley (15 September 1733 – 4 October 1806) was a British churchman, bishop of Rochester from 1793. He was also well versed in physics and mathematics, on which he wrote a number of papers and thus was elected a Fellow of the Royal So ...

testing for the influence of winds and of the moon on the barometer readings.J.L. Heilbron et al.: "The Quantifying Spirit in the 18th Century"Publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved on November 6, 2013. * 1777 –

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

* 1800 – The

* 1800 – The

CNRS (

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

and develops an explanation for combustion.

* 1780 – Charles Theodor charters the first international network of meteorological observers known as "Societas Meteorologica Palatina". The project collapses in 1795.

* 1780 – James Six invents the Six's thermometer

Six's maximum and minimum thermometer is a registering thermometer that can record the maximum and minimum temperatures reached over a period of time, for example 24 hours. It is used to record the extremes of temperature at a location, for inst ...

, a thermometer that records minimum and maximum temperatures. See (Six's thermometer

Six's maximum and minimum thermometer is a registering thermometer that can record the maximum and minimum temperatures reached over a period of time, for example 24 hours. It is used to record the extremes of temperature at a location, for inst ...

)

* 1783 – In Lavoisier's article "Reflexions sur le phlogistique", he deprecates the phlogiston theory and proposes a caloric theory of heat.

:: – First hair hygrometer

A hair tension dial hygrometer with a nonlinear scale.

A hygrometer is an instrument used to measure the amount of water vapor in air, in soil, or in confined spaces. Humidity measurement instruments usually rely on measurements of some other qu ...

demonstrated. The inventor was Horace-Bénédict de Saussure.

19th century

* 1800 – The

* 1800 – The Voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

was the first modern electric battery, invented by Alessandro Volta, which led to later inventions like the telegraph.

* 1802–1803 – Luke Howard

Luke Howard, (28 November 1772 – 21 March 1864) was a British manufacturing chemist and an amateur meteorologist with broad interests in science. His lasting contribution to science is a nomenclature system for clouds, which he proposed i ...

writes ''On the Modification of Clouds'' in which he assigns cloud types Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

names. Howard's system establishes three physical categories or ''forms'' based on appearance and process of formation: ''cirriform'' (mainly detached and wispy), ''cumuliform'' or convective

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convec ...

(mostly detached and heaped, rolled, or rippled), and non-convective ''stratiform'' (mainly continuous layers in sheets). These are cross-classified into ''lower'' and ''upper'' levels or étages. Cumuliform clouds forming in the lower level are given the genus name cumulus

Cumulus clouds are clouds which have flat bases and are often described as "puffy", "cotton-like" or "fluffy" in appearance. Their name derives from the Latin ''cumulo-'', meaning ''heap'' or ''pile''. Cumulus clouds are low-level clouds, gener ...

from the Latin word for ''heap'', while low stratiform clouds are given the genus name stratus

Stratus may refer to:

Weather

*Stratus cloud, a cloud type

**Nimbostratus cloud, a cloud type

**Stratocumulus cloud, a cloud type

**Altostratus cloud, a cloud type

**Altostratus undulatus cloud, a cloud type

**Cirrostratus cloud, a cloud type

Mus ...

from the Latin word for a flattened or spread out ''sheet''. Cirriform clouds are identified as always upper level and given the genus name cirrus

Cirrus may refer to:

Science

*Cirrus (biology), any of various thin, thread-like structures on the body of an animal

*Cirrus (botany), a tendril

* Infrared cirrus, in astronomy, filamentary structures seen in infrared light

*Cirrus cloud, a typ ...

from the Latin for ''hair''. From this genus name, the prefix ''cirro-'' is derived and attached to the names of upper level cumulus and stratus, yielding the names cirrocumulus

Cirrocumulus is one of the three main genus-types of high-altitude tropospheric clouds, the other two being cirrus and cirrostratus. They usually occur at an altitude of . Like lower-altitude cumuliform and stratocumuliform clouds, cirrocumulus s ...

, and cirrostratus

Cirrostratus is a high-level, very thin, generally uniform ''stratiform'' genus-type of cloud. It is made out of ice-crystals, which are pieces of frozen water. It is difficult to detect and it can make halos. These are made when the cloud takes ...

. In addition to these individual cloud types; Howard adds two names to designate cloud systems consisting of more than one form joined together or located in very close proximity. Cumulostratus describes large cumulus clouds blended with stratiform layers in the lower or upper levels. The term nimbus

Nimbus, from the Latin for "dark cloud", is an outdated term for the type of cloud now classified as the nimbostratus cloud. Nimbus also may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Halo (religious iconography), also known as ''Nimbus'', a ring of ligh ...

, taken from the Latin word for ''rain cloud'', is given to complex systems of cirriform, cumuliform, and stratiform clouds with sufficient vertical development to produce significant precipitation, and it comes to be identified as a distinct ''nimbiform'' physical category.

* 1804 – Sir John Leslie observes that a matte black surface radiates heat more effectively than a polished surface, suggesting the importance of black-body radiation.

* 1806 – Francis Beaufort introduces his system for classifying wind speeds.

* 1808 – John Dalton defends caloric theory in ''A New System of Chemistry'' and describes how it combines with matter, especially gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

es; he proposes that the heat capacity

Heat capacity or thermal capacity is a physical property of matter, defined as the amount of heat to be supplied to an object to produce a unit change in its temperature. The SI unit of heat capacity is joule per kelvin (J/K).

Heat capacity ...

of gases varies inversely with atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a giv ...

.

* 1810 – Sir John Leslie freezes water to ice artificially.

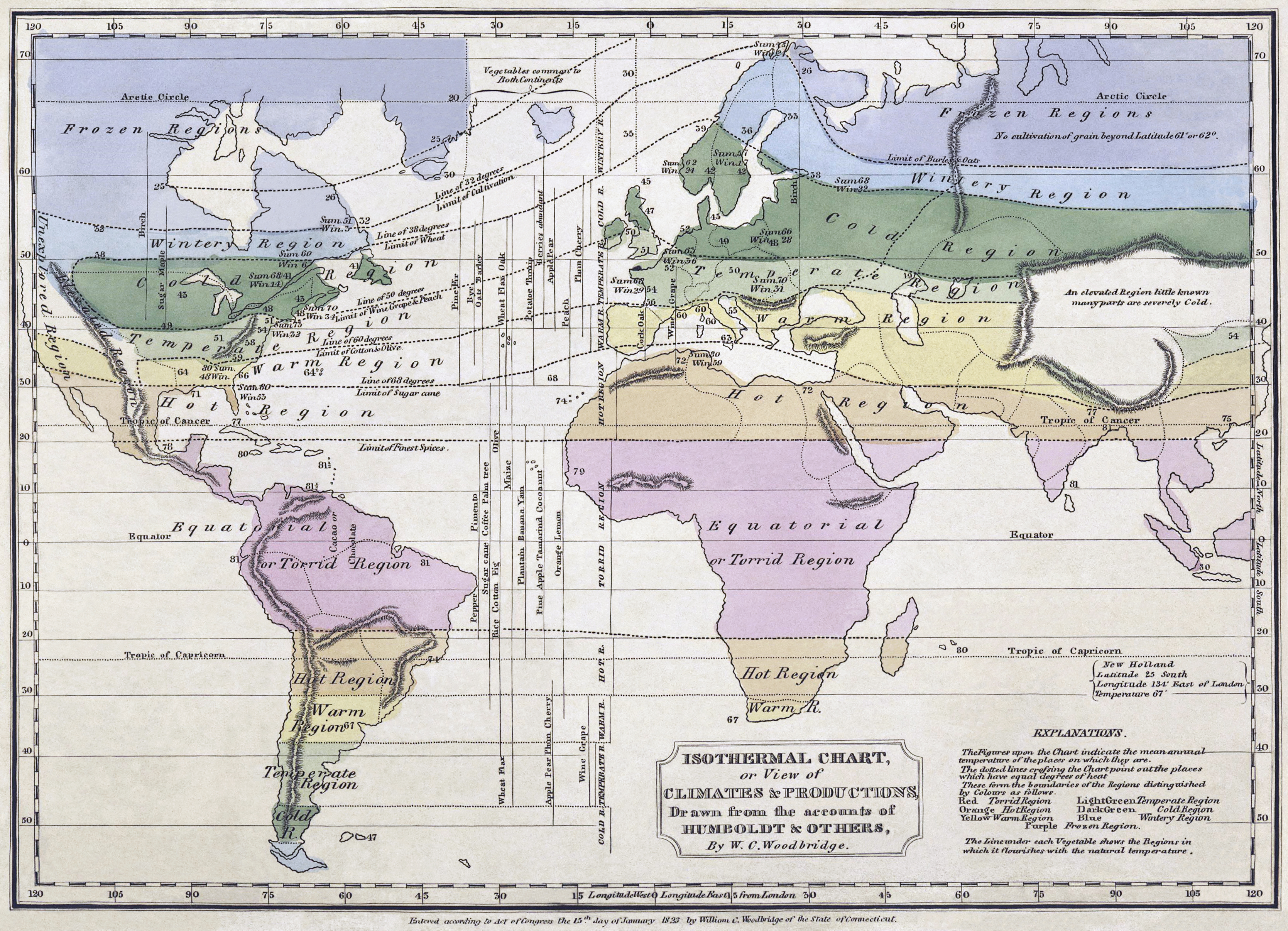

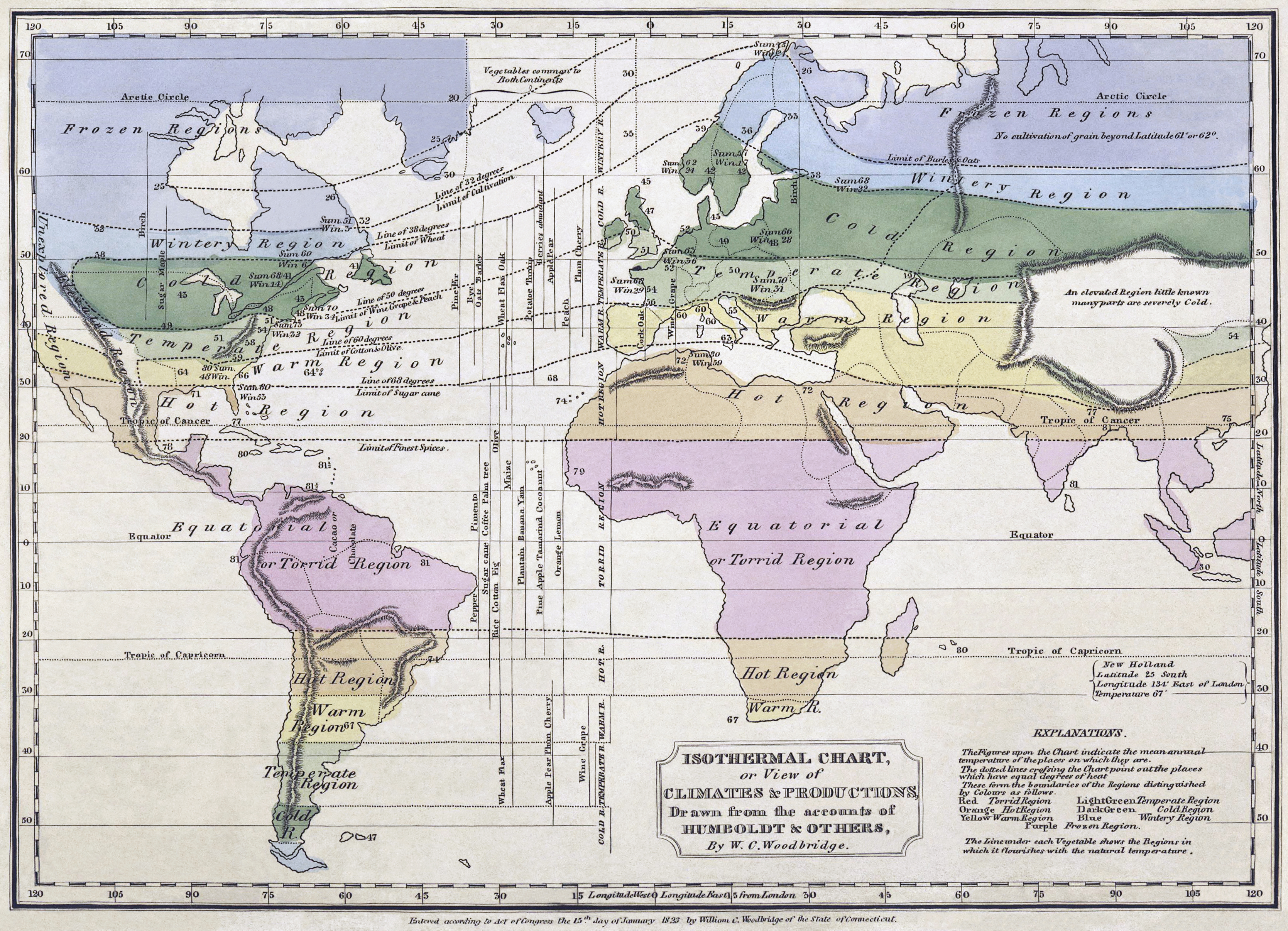

* 1817 – Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

publishes a global map of average temperature, the first global climate analysis.

* 1819 – Pierre Louis Dulong

Pierre Louis Dulong FRS FRSE (; ; 12 February 1785 – 19 July 1838) was a French physicist and chemist. He is remembered today largely for the law of Dulong and Petit, although he was much-lauded by his contemporaries for his studies into ...

and Alexis Thérèse Petit

Alexis Thérèse Petit (; 2 October 1791, Vesoul, Haute-Saône – 21 June 1820, Paris) was a French physicist.

Petit is known for his work on the efficiencies of air- and steam-engines, published in 1818 (''Mémoire sur l’emploi du principe ...

give the Dulong-Petit law for the specific heat capacity

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol ) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat t ...

of a crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

.

* 1820 – Heinrich Wilhelm Brandes publishes the first synoptic weather maps.

:: – John Herapath

John Herapath (30 May 1790 – 24 February 1868) was an English physicist who gave a partial account of the kinetic theory of gases in 1820 though it was neglected by the scientific community at the time. He was the cousin of William Herapath, t ...

develops some ideas in the kinetic theory of gases but mistakenly associates temperature with molecular momentum rather than kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its acc ...

; his work receives little attention other than from Joule.

* 1822 – Joseph Fourier formally introduces the use of dimension

In physics and mathematics, the dimension of a mathematical space (or object) is informally defined as the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it. Thus, a line has a dimension of one (1D) because only one coor ...

s for physical quantities in his ''Theorie Analytique de la Chaleur''.

* 1824 – Sadi Carnot analyzes the efficiency of steam engines using caloric theory; he develops the notion of a reversible process and, in postulating that no such thing exists in nature, lays the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal experience concerning heat and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unles ...

.

* 1827 – Robert Brown discovers the Brownian motion

Brownian motion, or pedesis (from grc, πήδησις "leaping"), is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas).

This pattern of motion typically consists of random fluctuations in a particle's position insi ...

of pollen and dye particles in water.

* 1832 – An electromagnetic telegraph was created by Baron Schilling.

* 1834 – Émile Clapeyron popularises Carnot's work through a graphical and analytic formulation.

* 1835 – Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis (; 21 May 1792 – 19 September 1843) was a French mathematician, mechanical engineer and scientist. He is best known for his work on the supplementary forces that are detected in a rotating frame of reference, l ...

publishes theoretical discussions of machines with revolving parts and their efficiency, for example the efficiency of waterwheels. At the end of the 19th century, meteorologists recognized that the way the Earth's rotation is taken into account in meteorology is analogous to what Coriolis discussed: an example of Coriolis Effect

In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial or fictitious force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the ...

.

* 1836 – An American scientist, Dr. David Alter, invented the first known American electric telegraph in Elderton, Pennsylvania, one year before the much more popular Morse telegraph was invented.

* 1837 – Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

independently developed an electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

, an alternative design that was capable of transmitting over long distances using poor quality wire. His assistant, Alfred Vail

Alfred Lewis Vail (September 25, 1807 – January 18, 1859) was an American machinist and inventor. Along with Samuel Morse, Vail was central in developing and commercializing American telegraphy between 1837 and 1844.

Vail and Morse were the f ...

, developed the Morse code signaling alphabet with Morse. The first electric telegram using this device was sent by Morse on May 24, 1844, from the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. to the B&O Railroad "outer depot" in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

and sent the message:

::'' What hath God wrought''

* 1839 – The ''first commercial'' electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

was constructed by Sir William Fothergill Cooke

Sir William Fothergill Cooke (4 May 1806 – 25 June 1879) was an English inventor. He was, with Charles Wheatstone, the co-inventor of the Cooke-Wheatstone electrical telegraph, which was patented in May 1837. Together with John Ricardo he f ...

and entered use on the Great Western Railway. Cooke and Wheatstone patented it in May 1837 as an alarm system.

* 1840 – Elias Loomis

Elias Loomis (August 7, 1811 – August 15, 1889) was an American mathematician. He served as a professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Western Reserve College (now Case Western Reserve University), the University of the City of New Yo ...

becomes the first person known to attempt to devise a theory on frontal zones. The idea of fronts do not catch on until expanded upon by the Norwegians in the years following World War I.

:: – German meteorologist Ludwig Kaemtz adds stratocumulus

A stratocumulus cloud, occasionally called a cumulostratus, belongs to a genus-type of clouds characterized by large dark, rounded masses, usually in groups, lines, or waves, the individual elements being larger than those in altocumulus, and th ...

to Howard's canon as a mostly detached low-étage genus of ''limited'' convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the conve ...

. It is defined as having cumuliform and stratiform characteristics integrated into a single layer (in contrast to cumulostratus which is deemed to be composite in nature and can be structured into more than one layer). This eventually leads to the formal recognition of a ''stratocumuliform'' physical category that includes rolled and rippled clouds classified separately from the more freely convective heaped cumuliform clouds.

* 1843 – John James Waterston fully expounds the kinetic theory of gases, but is ridiculed and ignored.

:: – James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule (; 24 December 1818 11 October 1889) was an English physicist, mathematician and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work (see energy). ...

experimentally finds the mechanical equivalent of heat.

* 1844 – Lucien Vidi

Lucien Vidie (1805, Nantes – April 1866, Nantes) was a French physicist. In 1844 he invented the barograph, that is, a device to monitor pressure, a recording aneroid barometer.

Passionate about his work, Vidi spent all his wealth to fund his r ...

invented the aneroid, from Greek meaning ''without liquid'', barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

.

* 1845 – Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance. In 1816 ...

invented the first successful camera for continuous recording of the variations in meteorological parameters over time

* 1845 – Francis Ronalds invented and named the storm clock, used to monitor rapid changes in meteorological parameters during extreme events

* 1846 – Cup anemometer invented by Dr. John Thomas Romney Robinson.

* 1847 – Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance. In 1816 ...

and William Radcliffe Birt described a stable kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

to make observations at altitude using self-recording instruments

* 1847 – Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

publishes a definitive statement of the conservation of energy, the first law of thermodynamics

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. It distinguishes in principle two forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work for a system of a constant amou ...

.

:: – The Manchester Examiner

The ''Manchester Examiner'' was a newspaper based in Manchester, England, that was founded around 1845–1846. Initially intended as an organ to promote the idea of Manchester Liberalism, a decline in its later years led to a takeover by a group w ...

newspaper organises the first weather reports collected by electrical means.

* 1848 – William Thomson extends the concept of absolute zero from gases to all substances.

* 1849 – Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

begins to establish an observation network across the United States, with 150 observers via telegraph, under the leadership of Joseph Henry.

:: – William John Macquorn Rankine

William John Macquorn Rankine (; 5 July 1820 – 24 December 1872) was a Scottish mechanical engineer who also contributed to civil engineering, physics and mathematics. He was a founding contributor, with Rudolf Clausius and William Thomson ( ...

calculates the correct relationship between saturated vapour pressure and temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various Conversion of units of temperature, temp ...

using his ''hypothesis of molecular vortices''.

* 1850 – Rankine uses his ''vortex'' theory to establish accurate relationships between the temperature, pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and e ...

, and density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

of gases, and expressions for the latent heat

Latent heat (also known as latent energy or heat of transformation) is energy released or absorbed, by a body or a thermodynamic system, during a constant-temperature process — usually a first-order phase transition.

Latent heat can be underst ...

of evaporation of a liquid; he accurately predicts the surprising fact that the apparent specific heat

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol ) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat t ...

of saturated steam

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization ...

will be negative.

:: – Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

gives the first clear joint statement of the first and second law of thermodynamics, abandoning the caloric theory, but preserving Carnot's principle.

* 1852 – Joule and Thomson demonstrate that a rapidly expanding gas cools, later named the Joule-Thomson effect.

* 1853 – The first International Meteorological Conference was held in Brussels at the initiative of Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and i ...

, U.S. Navy, recommending standard observing times, methods of observation and logging format for weather reports from ships at sea.

* 1854 – The French astronomer Leverrier showed that a storm in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

could be followed across Europe and would have been predictable if the telegraph had been used. A service of storm forecasts was established a year later by the Paris Observatory.

:: – Rankine introduces his ''thermodynamic function'', later identified as entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

.

* Mid 1850s – Emilien Renou, director of the Parc Saint-Maur and Montsouris observatories, begins work on an elaboration of Howard's classifications that would lead to the introduction during the 1870s of a newly defined ''middle'' étage . Clouds in this altitude range are given the prefix ''alto-'' derived from the Latin word ''altum'' pertaining to height above the low-level clouds. This resultes in the genus name altocumulus

Altocumulus (From Latin ''Altus'', "high", ''cumulus'', "heaped") is a middle-altitude cloud genus that belongs mainly to the ''stratocumuliform'' physical category characterized by globular masses or rolls in layers or patches, the individual ele ...

for mid-level cumuliform and stratocumuliform types and altostratus

Altostratus is a middle-altitude cloud genus made up of water droplets, ice crystals, or a mixture of the two. Altostratus clouds are formed when large masses of warm, moist air rise, causing water vapor to condense. Altostratus clouds are usuall ...

for stratiform types in the same altitude range.

* 1856 – William Ferrel

William Ferrel (January 29, 1817 – September 18, 1891) was an American meteorologist who developed theories that explained the mid-latitude atmospheric circulation cell in detail, and it is after him that the Ferrel cell is named.

Biograph ...

publishes his essay on the winds and the currents of the oceans.

* 1859 – James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

discovers the distribution law of molecular velocities.

* 1860 – Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

uses the new telegraph system to gather daily observations from across England and produces the first synoptic charts. He also coined the term "weather forecast" and his were the first ever daily weather forecasts to be published in this year.

:: – After establishment in 1849, 500 U.S. telegraph stations are now making weather observations and submitting them back to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. The observations are later interrupted by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

* 1865 – Josef Loschmidt applies Maxwell's theory to estimate the number-density of molecules in gases, given observed gas viscosities.

:: – Manila Observatory founded in the Philippines.

* 1869 – Joseph Lockyer starts the scientific journal ''Nature''.

* 1869 – The New York Meteorological Observatory opens, and begins to record wind, precipitation and temperature data.

* 1870 – The US Weather Bureau is founded. Data recorded in several Midwestern cities such as Chicago begins.

* 1870 – Benito Viñes becomes the head of the Meteorological Observatory at Belen in Havana, Cuba. He develops the first observing network in Cuba and creates some of the first hurricane-related forecasts.

* 1872 – The "Oficina Meteorológica Argentina" (today "Argentinean National Weather Service") is founded.

* 1872 – Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics, and the statistical explanation of the second law of ther ...

states the Boltzmann equation

The Boltzmann equation or Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) describes the statistical behaviour of a thermodynamic system not in a state of equilibrium, devised by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872.Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R. G. Lerne ...

for the temporal development of distribution functions in phase space, and publishes his H-theorem

In classical statistical mechanics, the ''H''-theorem, introduced by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872, describes the tendency to decrease in the quantity ''H'' (defined below) in a nearly-ideal gas of molecules.

L. Boltzmann,Weitere Studien über das Wä ...