Tichborne Case on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tichborne case was a legal ''

The Tichborne case was a legal ''

In 1803 the seventh baronet,

In 1803 the seventh baronet,

On 19 June 1853 ''La Pauline'' reached Valparaíso, where letters informed Roger that his father had succeeded to the baronetcy, Sir Edward having died in May. In all, Roger spent 10 months in South America, accompanied in the first stages by a family servant, John Moore. In the course of his inland travels he may have visited the small town of

On 19 June 1853 ''La Pauline'' reached Valparaíso, where letters informed Roger that his father had succeeded to the baronetcy, Sir Edward having died in May. In all, Roger spent 10 months in South America, accompanied in the first stages by a family servant, John Moore. In the course of his inland travels he may have visited the small town of  On 24 April 1854 a capsized ship's boat bearing the name ''Bella'' was discovered off the Brazilian coast, together with some wreckage but no personnel, and the ship's loss with all hands was assumed. The Tichborne family were told in June that Roger must be presumed lost, though they retained a faint hope, fed by rumours, that another ship had picked up survivors and taken them to Australia. Sir James Tichborne died in June 1862, at which point, if he was alive, Roger became the 11th baronet. As he was by then presumed dead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred, whose financial recklessness rapidly brought about his near-bankruptcy.Woodruff, pp. 32–33 Tichborne Park was vacated and leased to tenants.McWilliam 2007, p. 14–15

Encouraged by a clairvoyant's assurance that her elder son was alive and well, in February 1863 Roger's mother Henriette, now Lady Tichborne, began placing regular newspaper advertisements in ''

On 24 April 1854 a capsized ship's boat bearing the name ''Bella'' was discovered off the Brazilian coast, together with some wreckage but no personnel, and the ship's loss with all hands was assumed. The Tichborne family were told in June that Roger must be presumed lost, though they retained a faint hope, fed by rumours, that another ship had picked up survivors and taken them to Australia. Sir James Tichborne died in June 1862, at which point, if he was alive, Roger became the 11th baronet. As he was by then presumed dead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred, whose financial recklessness rapidly brought about his near-bankruptcy.Woodruff, pp. 32–33 Tichborne Park was vacated and leased to tenants.McWilliam 2007, p. 14–15

Encouraged by a clairvoyant's assurance that her elder son was alive and well, in February 1863 Roger's mother Henriette, now Lady Tichborne, began placing regular newspaper advertisements in ''' s last voyage and described Roger Tichborne as "of a delicate constitution, rather tall, with very light brown hair and blue eyes". A "most liberal reward" would be given "for any information that may definitely point out his fate".

In October 1865 Cubitt informed Lady Tichborne that William Gibbes, a lawyer from

In October 1865 Cubitt informed Lady Tichborne that William Gibbes, a lawyer from

After depositing his family in a London hotel, the Claimant called at Lady Tichborne's address and was told she was in Paris. He then went to Wapping in East London, where he enquired after a local family named Orton. Finding that they had left the area, he identified himself to a neighbour as a friend of Arthur Orton, who, he said, was now one of the wealthiest men in Australia. The significance of the Wapping visit would become apparent only later. On 29 December the Claimant visited Alresford and stayed at the Swan Hotel, where the landlord detected a resemblance to the Tichbornes. The Claimant confided that he was the missing Sir Roger but asked that this be kept secret. He also sought information concerning the Tichborne family.

Back in London, the Claimant employed a

After depositing his family in a London hotel, the Claimant called at Lady Tichborne's address and was told she was in Paris. He then went to Wapping in East London, where he enquired after a local family named Orton. Finding that they had left the area, he identified himself to a neighbour as a friend of Arthur Orton, who, he said, was now one of the wealthiest men in Australia. The significance of the Wapping visit would become apparent only later. On 29 December the Claimant visited Alresford and stayed at the Swan Hotel, where the landlord detected a resemblance to the Tichbornes. The Claimant confided that he was the missing Sir Roger but asked that this be kept secret. He also sought information concerning the Tichborne family.

Back in London, the Claimant employed a

The Claimant quickly acquired significant supporters; the Tichborne family's solicitor Edward Hopkins accepted him, as did J.P. Lipscomb, the family's doctor. Lipscomb, after a detailed medical examination, reported that the Claimant possessed a distinctive genital malformation. It would later be suggested that Roger Tichborne had this same defect, but this could not be established beyond speculation and hearsay. Many people were impressed by the Claimant's seeming ability to recall small details of Roger Tichborne's early life, such as the

The Claimant quickly acquired significant supporters; the Tichborne family's solicitor Edward Hopkins accepted him, as did J.P. Lipscomb, the family's doctor. Lipscomb, after a detailed medical examination, reported that the Claimant possessed a distinctive genital malformation. It would later be suggested that Roger Tichborne had this same defect, but this could not be established beyond speculation and hearsay. Many people were impressed by the Claimant's seeming ability to recall small details of Roger Tichborne's early life, such as the

The hearing, which took place within the

The hearing, which took place within the

From his cell in Newgate, the Claimant vowed to resume the fight as soon as he was acquitted.Woodruff, pp. 221–22 On 25 March 1872 he published in the ''

From his cell in Newgate, the Claimant vowed to resume the fight as soon as he was acquitted.Woodruff, pp. 221–22 On 25 March 1872 he published in the ''

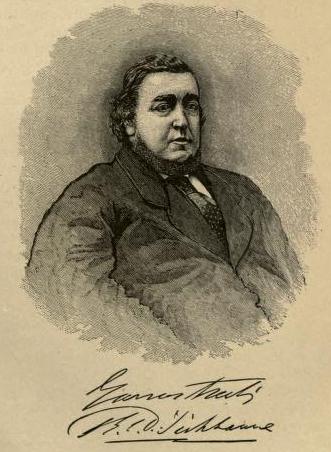

The criminal case, to be heard in the Queen's Bench, was listed as ''Regina v. Castro'', the name Castro being the last uncontested alias of the Claimant.Woodruff, pp. 251–52 Because of its expected length, the case was scheduled as a

The criminal case, to be heard in the Queen's Bench, was listed as ''Regina v. Castro'', the name Castro being the last uncontested alias of the Claimant.Woodruff, pp. 251–52 Because of its expected length, the case was scheduled as a

The trial, one of the lengthiest cases heard in an English court, began on 21 April 1873 and lasted until 28 February 1874, occupying 188 court days. The tone was dominated by Kenealy's confrontational style; his personal attacks extended not only to witnesses but to the Bench and led to frequent clashes with Cockburn. Under the legal rules that then applied to criminal cases, the Claimant, though present in court, was not allowed to testify. Away from the court he revelled in his celebrity status; the American writer

The trial, one of the lengthiest cases heard in an English court, began on 21 April 1873 and lasted until 28 February 1874, occupying 188 court days. The tone was dominated by Kenealy's confrontational style; his personal attacks extended not only to witnesses but to the Bench and led to frequent clashes with Cockburn. Under the legal rules that then applied to criminal cases, the Claimant, though present in court, was not allowed to testify. Away from the court he revelled in his celebrity status; the American writer  Kenealy's defence was that the Claimant was victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment. He frequently sought to demolish witnesses' character, as with Lord Bellew, whose reputation he destroyed by revealing details of the peer's adultery. Kenealy's own witnesses included Bogle and Biddulph, who remained steadfast, but more sensational testimony came from a sailor called Jean Luie, who claimed that he had been on the ''Osprey'' during the rescue mission. Luie identified the Claimant as "Mr Rogers", one of six survivors picked up and taken to Melbourne. On investigation Luie was found to be an impostor, a former prisoner who had been in England at the time of the ''Bellas sinking. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.

Kenealy's defence was that the Claimant was victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment. He frequently sought to demolish witnesses' character, as with Lord Bellew, whose reputation he destroyed by revealing details of the peer's adultery. Kenealy's own witnesses included Bogle and Biddulph, who remained steadfast, but more sensational testimony came from a sailor called Jean Luie, who claimed that he had been on the ''Osprey'' during the rescue mission. Luie identified the Claimant as "Mr Rogers", one of six survivors picked up and taken to Melbourne. On investigation Luie was found to be an impostor, a former prisoner who had been in England at the time of the ''Bellas sinking. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the Claimant. He and Kenealy were hailed as heroes, the latter as a martyr who had sacrificed his legal career.

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the Claimant. He and Kenealy were hailed as heroes, the latter as a martyr who had sacrificed his legal career.

The Claimant was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years.McWilliam 2007, pp. 183–85 He was much slimmer; a letter to Onslow dated May 1875 reports a loss of . Throughout his imprisonment he had maintained that he was Roger Tichborne, but on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with

The Claimant was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years.McWilliam 2007, pp. 183–85 He was much slimmer; a letter to Onslow dated May 1875 reports a loss of . Throughout his imprisonment he had maintained that he was Roger Tichborne, but on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with

The Tichborne case: a Victorian melodrama. Online at Discover Collections, State Library of New South Wales, Australia

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tichborne case 19th-century hoaxes Court of Common Pleas (England) cases Court of King's Bench (England) cases History of Hampshire Hoaxes in the United Kingdom Impostors Stonyhurst College Wagga Wagga

The Tichborne case was a legal ''

The Tichborne case was a legal ''cause célèbre

A cause célèbre (,''Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged'', 12th Edition, 2014. S.v. "cause célèbre". Retrieved November 30, 2018 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/cause+c%c3%a9l%c3%a8bre ,''Random House Kernerman Webs ...

'' that captivated Victorian England in the 1860s and 1870s. It concerned the claims by a man sometimes referred to as Thomas Castro or as Arthur Orton, but usually termed "the Claimant", to be the missing heir to the Tichborne baronetcy. He failed to convince the courts, was convicted of perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

and served a long prison sentence.

Roger Tichborne, heir to the family's title and fortunes, was presumed to have died in a shipwreck in 1854 at age 25. His mother clung to a belief that he might have survived, and after hearing rumours that he had made his way to Australia, she advertised extensively in Australian newspapers, offering a reward for information. In 1866, a Wagga Wagga

Wagga Wagga (; informally called Wagga) is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 56,000 as of June 2018, Wagga Wagga is the state's ...

butcher known as Thomas Castro came forward claiming to be Roger Tichborne. Although his manners and bearing were unrefined, he gathered support and travelled to England. He was instantly accepted by Lady Tichborne as her son, although other family members were dismissive and sought to expose him as an impostor.

During protracted enquiries before the case went to court in 1871, details emerged suggesting that the Claimant might be Arthur Orton, a butcher's son from Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

in London, who had gone to sea as a boy and had last been heard of in Australia. After a civil court

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

had rejected the Claimant's case, he was charged with perjury; while awaiting trial he campaigned throughout the country to gain popular support. In 1874, a criminal court jury decided that he was not Roger Tichborne and declared him to be Arthur Orton. Before passing a sentence of 14 years, the judge condemned the behaviour of the Claimant's counsel, Edward Kenealy

Edward Vaughan Hyde Kenealy QC (2 July 1819 – 16 April 1880) was an Irish barrister and writer. He is best remembered as counsel for the Tichborne claimant and the eccentric and disturbed conduct of the trial that led to his ruin.

Ear ...

, who was subsequently disbarred

Disbarment, also known as striking off, is the removal of a lawyer from a bar association or the practice of law, thus revoking their law license or admission to practice law. Disbarment is usually a punishment for unethical or criminal conduc ...

because of his conduct.

After the trial, Kenealy instigated a popular radical reform movement, the Magna Charta Association, which championed the Claimant's cause for some years. Kenealy was elected to Parliament in 1875 as a radical independent but was not an effective parliamentarian. The movement was in decline when the Claimant was released in 1884, and he had no dealings with it. In 1895, he confessed to being Orton, only to recant almost immediately. He lived generally in poverty for the rest of his life and was destitute at the time of his death in 1898. Although most commentators have accepted the court's view that the Claimant was Orton, some analysts believe that an element of doubt remains as to his true identity and that, conceivably, he was Roger Tichborne.

Sir Roger Tichborne

Tichborne family history

The Tichbornes, ofTichborne Park

Tichborne is a village and civil parish east of Winchester in Hampshire, England.

History

In archaeology in the south of the parish within the South Downs National Park is a bell barrow, bowl barrow and regular aggregate field system immediat ...

near Alresford in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

, were an old English Catholic family who had been prominent in the area since before the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

. After the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in the 16th century, although one of their number was hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

for complicity in the Babington Plot

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter sent by Mary (who had been imp ...

to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, the family in general remained loyal to the Crown, and in 1621 Benjamin Tichborne was created a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

for services to King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

.

In 1803 the seventh baronet,

In 1803 the seventh baronet, Sir Henry Tichborne

Sir Henry Tichborne PC (Ire) (1581–1667) was an English soldier and politician. He excelled at the Siege of Drogheda during the Irish Rebellion of 1641. He governed Ireland as one of the two Lord Justices from 1642 to 1644. In 1647, he foug ...

, was captured by the French in Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

and detained as a civil prisoner for some years. With him in captivity were his fourth son, James, and a nobly born Englishman, Henry Seymour of Knoyle. Despite his confinement, Seymour managed to conduct an affair with the daughter of the Duc de Bourbon

Duke of Bourbon (french: Duc de Bourbon) is a title in the peerage of France. It was created in the first half of the 14th century for the eldest son of Robert of France, Count of Clermont and Beatrice of Burgundy, heiress of the lordship of B ...

, as a result of which a daughter, Henriette Felicité, was born in about 1807. Years later, when Henriette had passed her 20th birthday and remained unmarried, Seymour thought his former companion James Tichborne might make a suitable husband—although James was close to his own age and was physically unprepossessing. The couple were married in August 1827; on 5 January 1829 Henriette gave birth to a son, Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne.

Sir Henry had been succeeded in 1821 by his eldest son, Henry Joseph, who fathered seven daughters but no male heir. As baronetcies are inherited only by males, when Henry Joseph died in 1845 the immediate heir was his younger brother Edward, who had assumed the surname of Doughty as a condition of a legacy. Edward's only son died in childhood, so James Tichborne became next in line to the baronetcy, and after him, Roger. As the family's fortunes had been greatly augmented by the Doughty bequest, this was a considerable material prospect.Woodruff, p. 2Annear, pp. 13–15

After Roger's birth, James and Henriette had three more children: two daughters who died in infancy and a second son, Alfred, born in 1839. The marriage was unhappy, and the couple spent much time apart, he in England, she in Paris with Roger. As a consequence of his upbringing, Roger spoke mainly French, and his English was heavily accented. In 1845 James decided that Roger should complete his education in England and placed him in the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

boarding school Stonyhurst College

Stonyhurst College is a co-educational Roman Catholic independent school, adhering to the Jesuit tradition, on the Stonyhurst Estate, Lancashire, England. It occupies a Grade I listed building. The school has been fully co-educational sinc ...

, where he remained until 1848. In 1849 he sat the British army entrance examinations and then took a commission in the 6th Dragoon Guards

The Carabiniers (6th Dragoon Guards) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army. It was formed in 1685 as the Lord Lumley's Regiment of Horse. It was renamed as His Majesty's 1st Regiment of Carabiniers in 1740, the 3rd Regiment of Horse (Carabi ...

, in which he served for three years, mainly in Ireland.

When on leave, Roger often stayed with his uncle Edward at Tichborne Park and became attracted to his cousin Katherine Doughty, four years his junior. Sir Edward and his wife, though they were fond of their nephew, did not consider marriage between first cousins desirable. At one point the young couple were forbidden to meet, though they continued to do so clandestinely. Feeling harassed and frustrated, Roger hoped to escape from the situation through a spell of overseas military duty; when it became clear that the regiment would remain in the British Isles, he resigned his commission. On 1 March 1853 he left for a private tour of South America on board ''La Pauline'', bound for Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

in Chile.

Travels and disappearance

On 19 June 1853 ''La Pauline'' reached Valparaíso, where letters informed Roger that his father had succeeded to the baronetcy, Sir Edward having died in May. In all, Roger spent 10 months in South America, accompanied in the first stages by a family servant, John Moore. In the course of his inland travels he may have visited the small town of

On 19 June 1853 ''La Pauline'' reached Valparaíso, where letters informed Roger that his father had succeeded to the baronetcy, Sir Edward having died in May. In all, Roger spent 10 months in South America, accompanied in the first stages by a family servant, John Moore. In the course of his inland travels he may have visited the small town of Melipilla

Melipilla (Mapudungun for "four Pillans") is a Chilean commune and capital city of the province of the same name, located in the Santiago Metropolitan Region southwest of the nation's capital. The commune spans an area of .

Demographics

Acco ...

, which lies on the route between Valparaíso and Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

. Moore, who had fallen ill, was paid off in Santiago, while Roger travelled to Peru, where he took a long hunting trip. By the end of 1853 he was back in Valparaíso, and early in the new year he began a crossing of the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

. At the end of January, he reached Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, where he wrote to his aunt, Lady Doughty, indicating that he was heading for Brazil, then Jamaica and finally Mexico. The last positive sightings of Roger were in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, in April 1854, awaiting a sea passage to Jamaica. Although he lacked a passport, he secured a berth on a ship, the ''Bella'', which sailed for Jamaica on 20 April.Annear, pp. 38–39

On 24 April 1854 a capsized ship's boat bearing the name ''Bella'' was discovered off the Brazilian coast, together with some wreckage but no personnel, and the ship's loss with all hands was assumed. The Tichborne family were told in June that Roger must be presumed lost, though they retained a faint hope, fed by rumours, that another ship had picked up survivors and taken them to Australia. Sir James Tichborne died in June 1862, at which point, if he was alive, Roger became the 11th baronet. As he was by then presumed dead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred, whose financial recklessness rapidly brought about his near-bankruptcy.Woodruff, pp. 32–33 Tichborne Park was vacated and leased to tenants.McWilliam 2007, p. 14–15

Encouraged by a clairvoyant's assurance that her elder son was alive and well, in February 1863 Roger's mother Henriette, now Lady Tichborne, began placing regular newspaper advertisements in ''

On 24 April 1854 a capsized ship's boat bearing the name ''Bella'' was discovered off the Brazilian coast, together with some wreckage but no personnel, and the ship's loss with all hands was assumed. The Tichborne family were told in June that Roger must be presumed lost, though they retained a faint hope, fed by rumours, that another ship had picked up survivors and taken them to Australia. Sir James Tichborne died in June 1862, at which point, if he was alive, Roger became the 11th baronet. As he was by then presumed dead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred, whose financial recklessness rapidly brought about his near-bankruptcy.Woodruff, pp. 32–33 Tichborne Park was vacated and leased to tenants.McWilliam 2007, p. 14–15

Encouraged by a clairvoyant's assurance that her elder son was alive and well, in February 1863 Roger's mother Henriette, now Lady Tichborne, began placing regular newspaper advertisements in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' offering a reward for information about Roger Tichborne and the fate of the ''Bella''. None of these produced results; however, in May 1865 Lady Tichborne saw an advertisement placed by Arthur Cubitt of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, Australia, on behalf of his "Missing Friends Agency". She wrote to him, and he agreed to place a series of notices in Australian newspapers. These gave details of the ''Bella''Claimant appears

In Australia

In October 1865 Cubitt informed Lady Tichborne that William Gibbes, a lawyer from

In October 1865 Cubitt informed Lady Tichborne that William Gibbes, a lawyer from Wagga Wagga

Wagga Wagga (; informally called Wagga) is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 56,000 as of June 2018, Wagga Wagga is the state's ...

, had identified Roger Tichborne in the person of a bankrupt local butcher using the name Thomas Castro.Woodruff, pp. 38–40 During his bankruptcy examination Castro had mentioned an entitlement to property in England. He had also talked of experiencing a shipwreck and was smoking a briar pipe which carried the initials "R.C.T." When challenged by Gibbes to reveal his true name, Castro had initially been reticent but eventually agreed that he was indeed the missing Roger Tichborne; henceforth he became generally known as the Claimant.

Cubitt offered to accompany the supposed lost son back to England and wrote to Lady Tichborne requesting funds. Meanwhile, Gibbes asked the Claimant to make out a will and to write to his mother. The will incorrectly gave Lady Tichborne's name as "Hannah Frances", and disposed of numerous nonexistent parcels of supposed Tichborne property. In the letter to his mother, the Claimant's references to his former life were vague and equivocal but were enough to convince Lady Tichborne that he was her elder son. Her willingness to accept the Claimant may have been influenced by the death of her younger son, Alfred, in February.Woodruff, pp. 45–48

In June 1866 the Claimant moved to Sydney, where he was able to raise money from banks on the basis of a statutory declaration that he was Roger Tichborne. The statement was later found to contain many errors, although the birthdate and parentage details were given correctly. It included a brief account of how he had arrived in Australia: he and others from the sinking ''Bella'', he said, had been picked up by the ''Osprey'', bound for Melbourne.Woodruff, pp. 52–54 On arrival he had taken the name Thomas Castro from an acquaintance from Melipilla and had wandered for some years before settling in Wagga Wagga. He had married a pregnant housemaid, Mary Ann Bryant, and taken her child, a daughter, as his own; a further daughter had been born in March 1866.

While in Sydney the Claimant encountered two former servants of the Tichborne family. One was a gardener, Michael Guilfoyle, who at first acknowledged the identity of Roger Tichborne but later changed his mind when asked to provide money to facilitate the return to England. The second, Andrew Bogle, was a former slave at the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos

Viscount Cobham is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain that was created in 1718. Owing to its special remainder, the title has passed through several families. Since 1889, it has been held by members of the Lyttelton family.

The barony a ...

's plantation in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

who had thereafter worked for Sir Edward for many years before retiring. The elderly Bogle did not immediately recognise the Claimant, whose weight contrasted sharply with Roger's remembered slender build; however, Bogle quickly accepted that the Claimant was Roger, and remained convinced until the end of his life. On 2 September 1866 the Claimant, having received funds from England, sailed from Sydney on board the ''Rakaia'' with his wife and children in first class, and a small retinue including Bogle and his youngest son Henry George in second class.Woodruff, pp. 55–56 Good living in Sydney had raised his weight on departure to , and during the long voyage he added another . After a journey involving several changes of ship, the party arrived at Tilbury

Tilbury is a port town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. The present town was established as separate settlement in the late 19th century, on land that was mainly part of Chadwell St Mary. It contains a 16th century fort and an anc ...

on 25 December 1866.

Recognition in France

After depositing his family in a London hotel, the Claimant called at Lady Tichborne's address and was told she was in Paris. He then went to Wapping in East London, where he enquired after a local family named Orton. Finding that they had left the area, he identified himself to a neighbour as a friend of Arthur Orton, who, he said, was now one of the wealthiest men in Australia. The significance of the Wapping visit would become apparent only later. On 29 December the Claimant visited Alresford and stayed at the Swan Hotel, where the landlord detected a resemblance to the Tichbornes. The Claimant confided that he was the missing Sir Roger but asked that this be kept secret. He also sought information concerning the Tichborne family.

Back in London, the Claimant employed a

After depositing his family in a London hotel, the Claimant called at Lady Tichborne's address and was told she was in Paris. He then went to Wapping in East London, where he enquired after a local family named Orton. Finding that they had left the area, he identified himself to a neighbour as a friend of Arthur Orton, who, he said, was now one of the wealthiest men in Australia. The significance of the Wapping visit would become apparent only later. On 29 December the Claimant visited Alresford and stayed at the Swan Hotel, where the landlord detected a resemblance to the Tichbornes. The Claimant confided that he was the missing Sir Roger but asked that this be kept secret. He also sought information concerning the Tichborne family.

Back in London, the Claimant employed a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, John Holmes, who agreed to go with him to Paris to meet Lady Tichborne. This meeting took place on 11 January at the Hôtel de Lille. As soon as she saw his face, Lady Tichborne accepted him. At Holmes's behest she lodged with the British Embassy a signed declaration formally testifying that the Claimant was her son. She was unmoved when Father Châtillon, Roger's childhood tutor, declared the Claimant an impostor, and she allowed Holmes to inform ''The Times'' in London that she had recognised Roger. She settled an income of £1,000 a year on him, and accompanied him to England to declare her support before the more sceptical members of the Tichborne family.McWilliam 2007, p. 23

Laying the groundwork, 1867–71

Support and opposition

The Claimant quickly acquired significant supporters; the Tichborne family's solicitor Edward Hopkins accepted him, as did J.P. Lipscomb, the family's doctor. Lipscomb, after a detailed medical examination, reported that the Claimant possessed a distinctive genital malformation. It would later be suggested that Roger Tichborne had this same defect, but this could not be established beyond speculation and hearsay. Many people were impressed by the Claimant's seeming ability to recall small details of Roger Tichborne's early life, such as the

The Claimant quickly acquired significant supporters; the Tichborne family's solicitor Edward Hopkins accepted him, as did J.P. Lipscomb, the family's doctor. Lipscomb, after a detailed medical examination, reported that the Claimant possessed a distinctive genital malformation. It would later be suggested that Roger Tichborne had this same defect, but this could not be established beyond speculation and hearsay. Many people were impressed by the Claimant's seeming ability to recall small details of Roger Tichborne's early life, such as the fly fishing tackle

Fly fishing tackle comprises the fishing tackle or equipment typically used by fly anglers. Fly fishing tackle includes:

* Artificial flies - ultralight fishing lure used to imitate flying insects and small crustaceans

* Fly rods - a specialized ...

he had used. Several soldiers who had served with Roger in the Dragoons, including his former batman

Batman is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in the 27th issue of the comic book ''Detective Comics'' on March 30, 1939. I ...

Thomas Carter, recognised the Claimant as Roger.McWilliam 2007, p. 24 Other notable supporters included Lord Rivers, a landowner and sportsman, and Guildford Onslow

Guildford James Hillier Mainwaring-Ellerker-Onslow (29 March 1814 – 20 August 1882) was an English Liberal Party politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1858 to 1874.

Guildford Onslow was the second of five sons of Colonel Thomas Cranl ...

, the Liberal Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

who became one of the Claimant's staunchest advocates. Rohan MacWilliam, in his account of the case, calls this wide degree of recognition remarkable, particularly given the Claimant's increasing physical differences from the slim Roger. By mid-June 1867 the Claimant's weight had reached almost and would increase even more in the ensuing years.McWilliam 2007, pp. 25–26

Despite Lady Tichborne's insistence that the Claimant was her son, the rest of the Tichbornes and their related families were almost unanimous in declaring him a fraud. They recognised Alfred Tichborne's infant son, Henry Alfred, as the 12th baronet. Lady Doughty, Sir Edward's widow, had initially accepted the evidence from Australia but changed her mind soon after the Claimant's arrival in England. Lady Tichborne's brother Henry Seymour denounced the Claimant as false when he found that the latter neither spoke nor understood French (Roger's first language as a child) and lacked any trace of a French accent. The Claimant was unable to identify several family members and complained about attempts to catch him out by presenting him with impostors. Vincent Gosford, a former Tichborne Park steward, was unimpressed by the Claimant, who, when asked to name the contents of a sealed package that Roger left with Gosford before his departure in 1853, said he could not remember.Woodruff, pp. 90–91 The family believed that the Claimant had acquired from Bogle and other sources information that enabled him to demonstrate some knowledge of the family's affairs, including, for example, the locations of certain pictures in Tichborne Park. Apart from Lady Tichborne, a distant cousin, Anthony John Wright Biddulph, was the only relation who accepted the Claimant as genuine; however, as long as Lady Tichborne was alive and maintaining her support, the Claimant's position remained strong.

On 31 July 1867 the Claimant underwent a judicial examination at the Chancery Division

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Senior Courts of England and Wales. Its name is abbreviated as EWHC (England ...

of the Royal Courts of Justice

The Royal Courts of Justice, commonly called the Law Courts, is a court building in Westminster which houses the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales. The High Court also sits on circuit and in other major cities. Designed by Ge ...

.Woodruff, pp. 94–96 He testified that after his arrival in Melbourne in July 1854 he had worked for William Foster at a cattle station in Gippsland

Gippsland is a rural region that makes up the southeastern part of Victoria, Australia, mostly comprising the coastal plains to the rainward (southern) side of the Victorian Alps (the southernmost section of the Great Dividing Range). It cove ...

under the name of Thomas Castro. While there, he had met Arthur Orton, a fellow Englishman. After leaving Foster's employment the Claimant had subsequently wandered the country, sometimes with Orton, working in various capacities before setting up as a butcher in Wagga Wagga in 1865. On the basis of this information, the Tichborne family sent an agent, John Mackenzie, to Australia to make further enquiries. Mackenzie located Foster's widow, who produced the old station records. These showed no reference to "Thomas Castro", although the employment of an "Arthur Orton" was recorded. Foster's widow also identified a photograph of the Claimant as Arthur Orton, thus providing the first direct evidence that the Claimant might in fact be Orton. In Wagga Wagga one local resident recalled the butcher Castro saying that he had learned his trade in Wapping.McWilliam 2007, pp. 28–30 When this information reached London, enquiries were made in Wapping by a private detective, ex-police inspector Jack Whicher, and the Claimant's visit in December 1866 was revealed.

Arthur Orton

Arthur Orton, a butcher's son born on 20 March 1834 in Wapping, had gone to sea as a boy and had been in Chile in the early 1850s. Sometime in 1852 he arrived inHobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/ Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, Tasmania, in the transport ship ''Middleton'' and later moved to mainland Australia. His employment by Foster at Gippsland terminated around 1857 with a dispute over wages. Thereafter he disappears; if he was not Castro, there is no further direct evidence of Orton's existence, although strenuous efforts were made to find him. The Claimant hinted that some of his activities with Orton were of a criminal nature and that to confound the authorities they had sometimes exchanged names. Most of Orton's family failed to recognise the Claimant as their long-lost kinsman, although it was later revealed that he had paid them money. However, a former sweetheart of Orton's, Mary Ann Loder, did identify the Claimant as Orton.

Financial problems

Lady Tichborne died on 12 March 1868, thus depriving the Claimant of his principal advocate and his main source of income. He outraged the family by insisting on taking the position of chief mourner at her funeral mass. His lost income was rapidly replaced by a fund, set up by supporters, that provided a house near Alresford and an income of £1,400 (£145,278 in 2016) a year. In September 1868, together with his legal team, the Claimant went to South America to meet face-to-face with potential witnesses in Melipilla who might confirm his identity. He disembarked atBuenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, ostensibly to travel to Valparaíso overland and there rejoin his advisers who were continuing by sea. After waiting two months in Buenos Aires he caught a ship home. His explanations for this sudden retreat—poor health and the dangers from brigands—did not convince his backers, many of whom withdrew their support; Holmes resigned as his solicitor. Furthermore, on their return his advisers reported that no one in Melipilla had heard of "Tichborne", although they remembered a young English sailor called "Arturo".McWilliam 2007, pp. 31–32

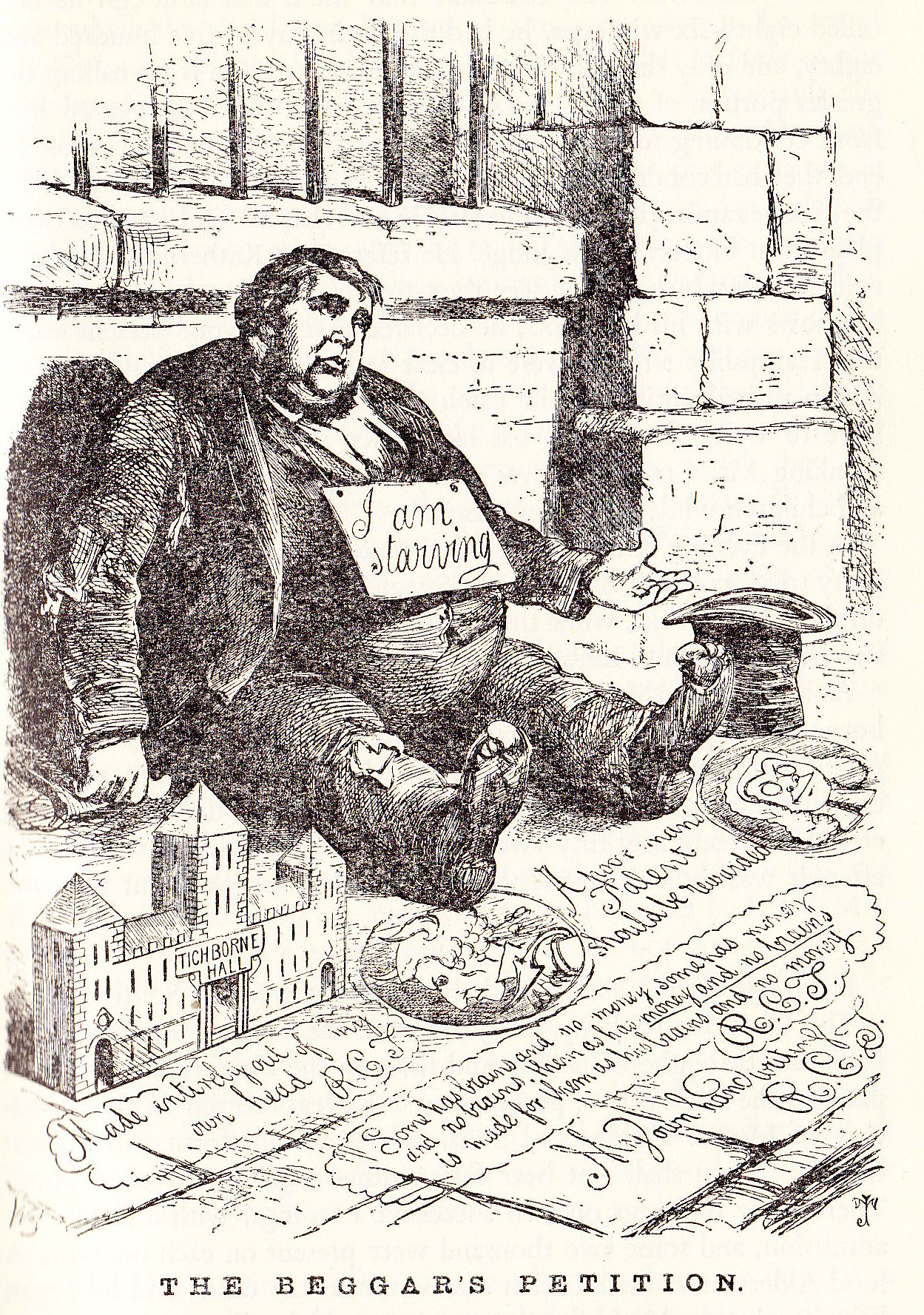

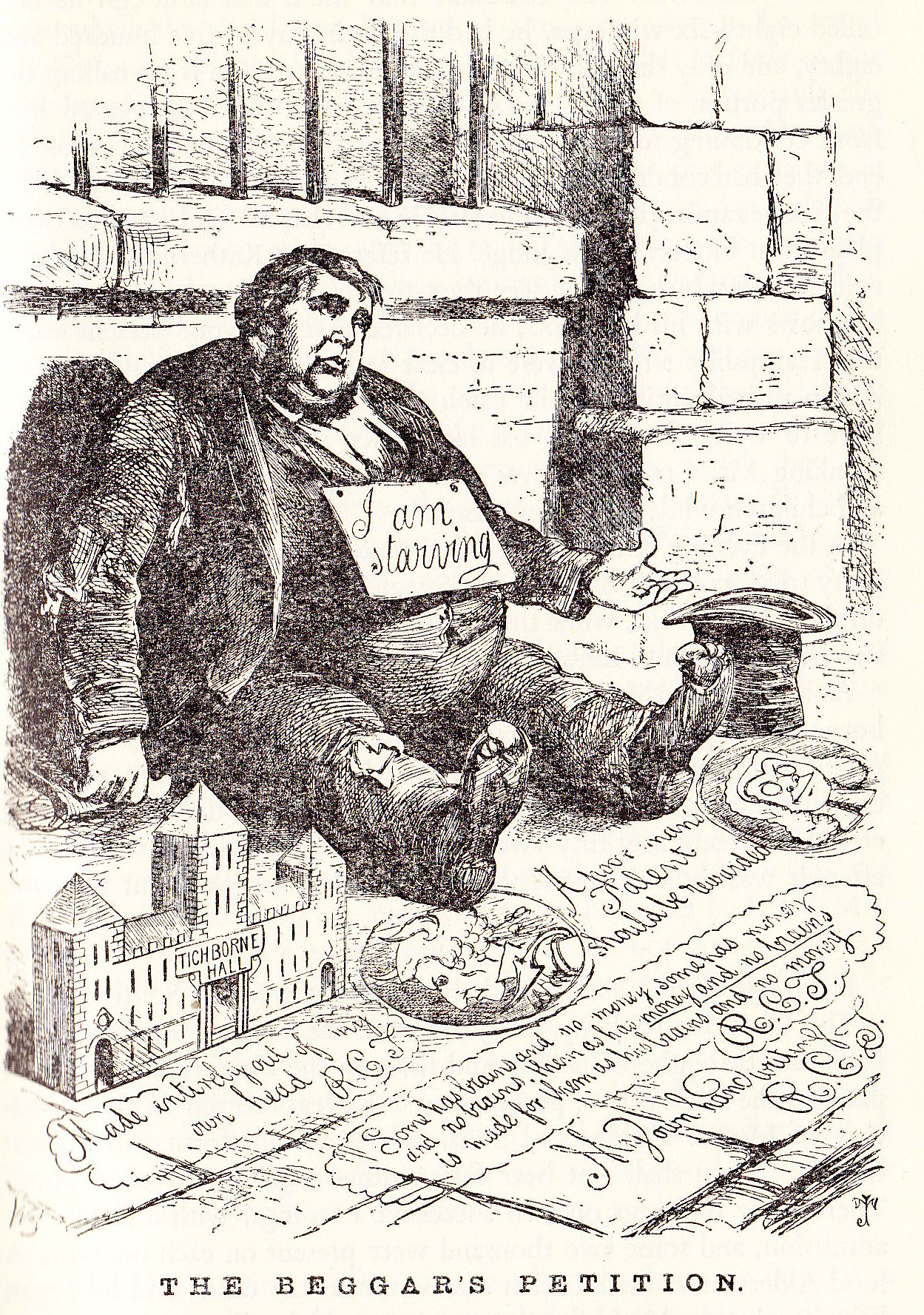

The Claimant was now bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor ...

. In 1870 his new legal advisers launched a novel fundraising scheme: Tichborne Bonds, an issue of 1,000 debentures

In corporate finance, a debenture is a medium- to long-term debt instrument used by large companies to borrow money, at a fixed rate of interest. The legal term "debenture" originally referred to a document that either creates a debt or acknowle ...

of £100 face value, the holders of which would be repaid with interest when the Claimant obtained his inheritance. About £40,000 was raised, though the bonds quickly traded at a considerable discount and were soon being exchanged for derisory sums. The scheme allowed the Claimant to continue to meet his living and legal expenses for a while. After a delay while the Franco-Prussian War and its aftermath prevented key witnesses from leaving Paris, the civil case that the Claimant hoped would confirm his identity finally came to court in May 1871.

Civil case: ''Tichborne v. Lushington'', 1871–72

The case was listed in theCourt of Common Pleas

A court of common pleas is a common kind of court structure found in various common law jurisdictions. The form originated with the Court of Common Pleas at Westminster, which was created to permit individuals to press civil grievances against one ...

as ''Tichborne v. Lushington'', in the form of an action for the ejectment

Ejectment is a common law term for civil action to recover the possession of or title to land. It replaced the old real actions and the various possessory assizes (denoting county-based pleas to local sittings of the courts) where boundary dis ...

of Colonel Lushington, the tenant of Tichborne Park. The real purpose, however, was to establish the Claimant's identity as Sir Roger Tichborne and his rights to the family's estates; failure on his part would expose him as an impostor. In addition to Tichborne Park's , the estates included manors, lands and farms in Hampshire, and considerable properties in London and elsewhere, which altogether produced an annual income of over £20,000, equivalent to several millions in 21st-century terms.

Evidence and cross-examination

The hearing, which took place within the

The hearing, which took place within the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

, began on 11 May 1871 before Sir William Bovill, who was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, which was the second-highest common law court in the English legal system until 1875, when it, along with the othe ...

. The Claimant's legal team was led by William Ballantine

Serjeant William Ballantine SL (3 January 1812 – 9 January 1887) was an English Serjeant-at-law, a legal position defunct since the legal reforms of the 1870s.

Early career

Born in Howland Street, Tottenham Court Road in Camden, London, the ...

and Harding Giffard, both highly experienced advocates. Opposing them, acting on instructions from the bulk of the Tichborne family, were John Duke Coleridge, the Solicitor General (he was promoted to Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

during the hearing), and Henry Hawkins, a future High Court judge who was then at the height of his powers as a cross-examiner. In his opening speech, Ballantine made much of Roger Tichborne's unhappy childhood, his overbearing father, his poor education and his frequently unwise choices of companions. The Claimant's experiences in an open boat following the wreck of the ''Bella'' had, said Ballantine, impaired his memories of his earlier years, which explained his uncertain recall.McWilliam 2007, p. 43 Attempts to identify his client as Arthur Orton were, Ballantine argued, the concoctions of "irresponsible" private investigators acting for the Tichborne family.

The first witnesses for the Claimant included former officers and men from Roger Tichborne's regiment, all of whom declared their belief that he was genuine. Among servants and former servants of the Tichborne family called by Ballantine was John Moore, Roger's valet in South America. He testified that the Claimant had remembered many small details of their months together, including clothing worn and the name of a pet dog the pair had adopted. Roger's cousin Anthony Biddulph explained that he had accepted the Claimant only after spending much time in his company.

On 30 May Ballantine called the Claimant to the stand. During his examination-in-chief, the Claimant answered questions on Arthur Orton, whom he described as "a large-boned man with sharp features and a lengthy face slightly marked with smallpox". He had lost sight of Orton between 1862 and 1865, but they had met again in Wagga Wagga, where the Claimant had discussed his inheritance. Under cross-examination the Claimant was evasive when pressed for further details of his relationship with Orton, saying that he did not wish to incriminate himself. After questioning him on his visit to Wapping, Hawkins asked him directly: "Are you Arthur Orton?" to which he replied "I am not". The Claimant displayed considerable ignorance when questioned about his time at Stonyhurst. He could not identify Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, confused Latin with Greek, and did not understand what chemistry was. He caused a sensation when he declared that he had seduced Katherine Doughty and that the sealed package given to Gosford, the contents of which he earlier claimed not to recall, contained instructions to be followed in the event of her pregnancy. Rohan McWilliam, in his chronicle of the affair, comments that from that point on the Tichborne family were fighting not only for their estates but for Katherine Doughty's honour.McWilliam 2007, pp. 49–50

Collapse of case

On 7 July the court adjourned for four months. When it resumed, Ballantine called more witnesses, including Bogle and Francis Baigent, a close family friend. Hawkins contended that Bogle and Baigent were feeding the Claimant with information, but in cross-examination he could not dent their belief that the Claimant was genuine. In January 1872 Coleridge began the case for the defence with a speech during which he categorised the Claimant as comparable with "the great impostors of history".McWilliam 2007, pp. 51–52 He intended to prove that the Claimant was Arthur Orton. He had over 200 witnesses lined up, but it transpired that few were required.Lord Bellew

Baron Bellew, of Barmeath in the County of Louth, is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 17 July 1848 for Patrick Bellew, 1st Baron Bellew, Sir Patrick Bellew, 7th Baronet, who had previously represented County Louth (UK Parliament ...

, who had known Roger Tichborne at Stonyhurst, testified that Roger had distinctive body tattoos

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several tattooing ...

which the Claimant did not possess. On 4 March the jury notified the judge that they had heard enough and were ready to reject the Claimant's suit. Having ascertained that this decision was based on the evidence as a whole and not solely on the missing tattoos, Bovill ordered the Claimant's arrest on charges of perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

and committed him to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

.

Appeal to the public, 1872–73

From his cell in Newgate, the Claimant vowed to resume the fight as soon as he was acquitted.Woodruff, pp. 221–22 On 25 March 1872 he published in the ''

From his cell in Newgate, the Claimant vowed to resume the fight as soon as he was acquitted.Woodruff, pp. 221–22 On 25 March 1872 he published in the ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' an "Appeal to the Public", requesting financial help to meet his legal and living costs: "I appeal to every British soul who is inspired by a love of justice and fair play, and is willing to defend the weak against the strong".Woodruff, pp. 223–24 The Claimant had gained considerable popular support during the civil trial; his fight was perceived by many as symbolising the problems faced by the working class when seeking justice in the courts. In the wake of his appeal, support committees were formed throughout the country. When he was bailed early in April, on sureties provided by Lord Rivers and Guildford Onslow, a large crowd cheered him as he left the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

.

At a public meeting in Alresford on 14 May, Onslow reported that subscriptions to the defence fund were already pouring in and that invitations to visit and speak had been received from many towns. As the Claimant addressed meetings up and down the country, journalists following the campaign often commented on his pronounced cockney accent

Cockney is an accent and dialect of English, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by working-class and lower middle-class Londoners. The term "Cockney" has traditionally been used to describe a person from the East End, or ...

, suggestive of East London origins. The campaign drew in some high-level supporters, among whom was George Hammond Whalley

George Hammond Whalley (22 January 1813 – 8 October 1878) was a British lawyer and Liberal Party politician.

He was the eldest son of James Whalley, a merchant and banker from Gloucester, and a direct descendant of Edward Whalley, the regici ...

, a controversial anti-Catholic who was MP for Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire unti ...

. He and Onslow were sometimes incautious in their speeches; after a meeting in St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

, London, on 11 December 1872, each made specific charges against the Attorney General and the Government of trying to pervert the course of justice. They were fined £100 each for contempt of court.

With few exceptions, the mainstream press was hostile to the Claimant's campaign. To counteract this, his supporters launched two short-lived newspapers, the ''Tichborne Gazette'' in May 1872 and the ''Tichborne News and Anti-Oppression Journal'' in June. The former was wholly devoted to the Claimant's cause and ran until Onslow's and Whalley's contempt convictions in December 1872. The ''Tichborne News'', which concerned itself with a broader range of perceived injustices, closed after four months.

Criminal case: ''Regina v. Castro'', 1873–74

Judges and counsel

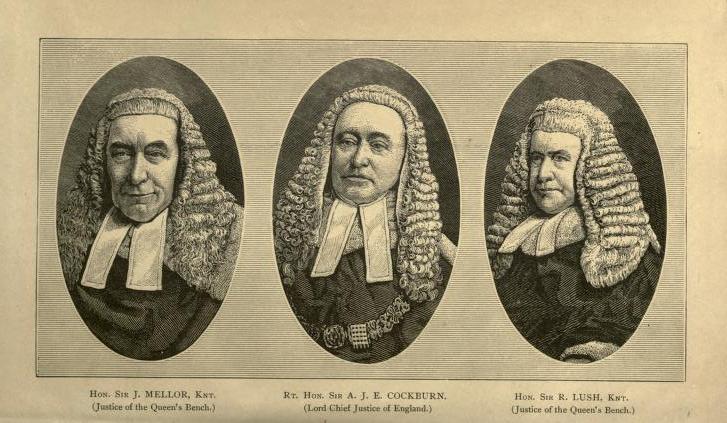

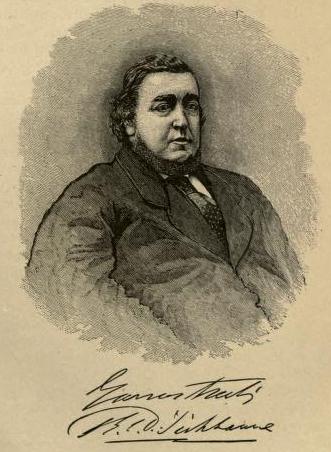

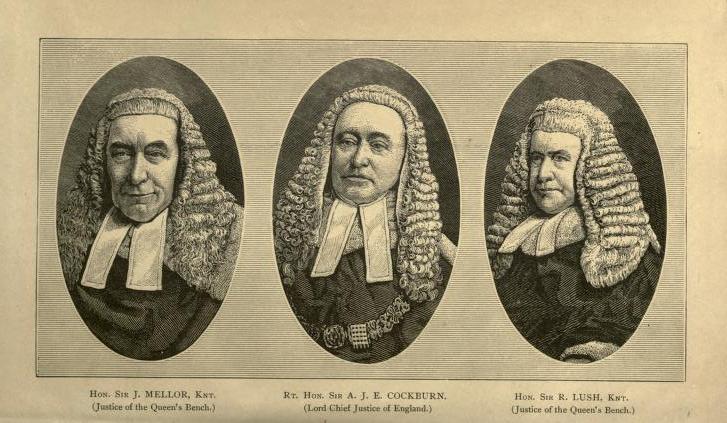

The criminal case, to be heard in the Queen's Bench, was listed as ''Regina v. Castro'', the name Castro being the last uncontested alias of the Claimant.Woodruff, pp. 251–52 Because of its expected length, the case was scheduled as a

The criminal case, to be heard in the Queen's Bench, was listed as ''Regina v. Castro'', the name Castro being the last uncontested alias of the Claimant.Woodruff, pp. 251–52 Because of its expected length, the case was scheduled as a trial at bar A trial at bar is a trial before two more judges. The procedure was often used in cases which raised novel points of law or for high-profile trials. Among famous trials at bar are the trials of Sir Roger Casement and Dr Leander Starr Jameson,

In ...

, a device that allowed a panel rather than one judge to hear it. The president of the panel was Sir Alexander Cockburn, the Lord Chief Justice

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

.McWilliam 2007, pp. 89–90 His decision to hear this case was controversial, since during the civil case he had publicly denounced the Claimant as a perjurer and a slanderer. Cockburn's co-judges were Sir John Mellor and Sir Robert Lush

Sir Robert Lush (25 October 1807 – 27 December 1881) was an English judge who served on many Commissions and Committees of Judges.

Born at Shaftesbury, he was educated at Gray's Inn before being called to the Bar in 1840. He earned a reputati ...

, experienced Queen's Bench justices.

The prosecution team was largely that which had opposed the Claimant in the civil case, minus Coleridge. Hawkins led the team, his main assistants being Charles Bowen and James Mathew.McWilliam 2007, p. 88 The Claimant's team was significantly weaker; he would not re-engage Ballantine and his other civil case lawyers declined to act for him again. Others refused the case, possibly because they knew they would have to present evidence concerning the seduction of Katherine Doughty. The Claimant's backers eventually engaged Edward Kenealy

Edward Vaughan Hyde Kenealy QC (2 July 1819 – 16 April 1880) was an Irish barrister and writer. He is best remembered as counsel for the Tichborne claimant and the eccentric and disturbed conduct of the trial that led to his ruin.

Ear ...

, an Irish lawyer of acknowledged gifts but known eccentricity. Kenealy had previously featured in several prominent defences, including those of the poisoner William Palmer and the leaders of the 1867 Fenian Rising

The Fenian Rising of 1867 ( ga, Éirí Amach na bhFíníní, 1867, ) was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

After the suppression of the ''Irish People'' newspaper in September 186 ...

. He was assisted by undistinguished juniors: Patrick MacMahon, an Irish MP who was frequently absent, and the young and inexperienced Cooper Wyld. Kenealy's task was made more difficult when several of his upper-class witnesses refused to appear, perhaps afraid of the ridicule they anticipated from the Crown's lawyers. Other important witnesses from the civil case, including Moore, Baigent and Lipscombe, would not give evidence at the criminal trial.

Trial

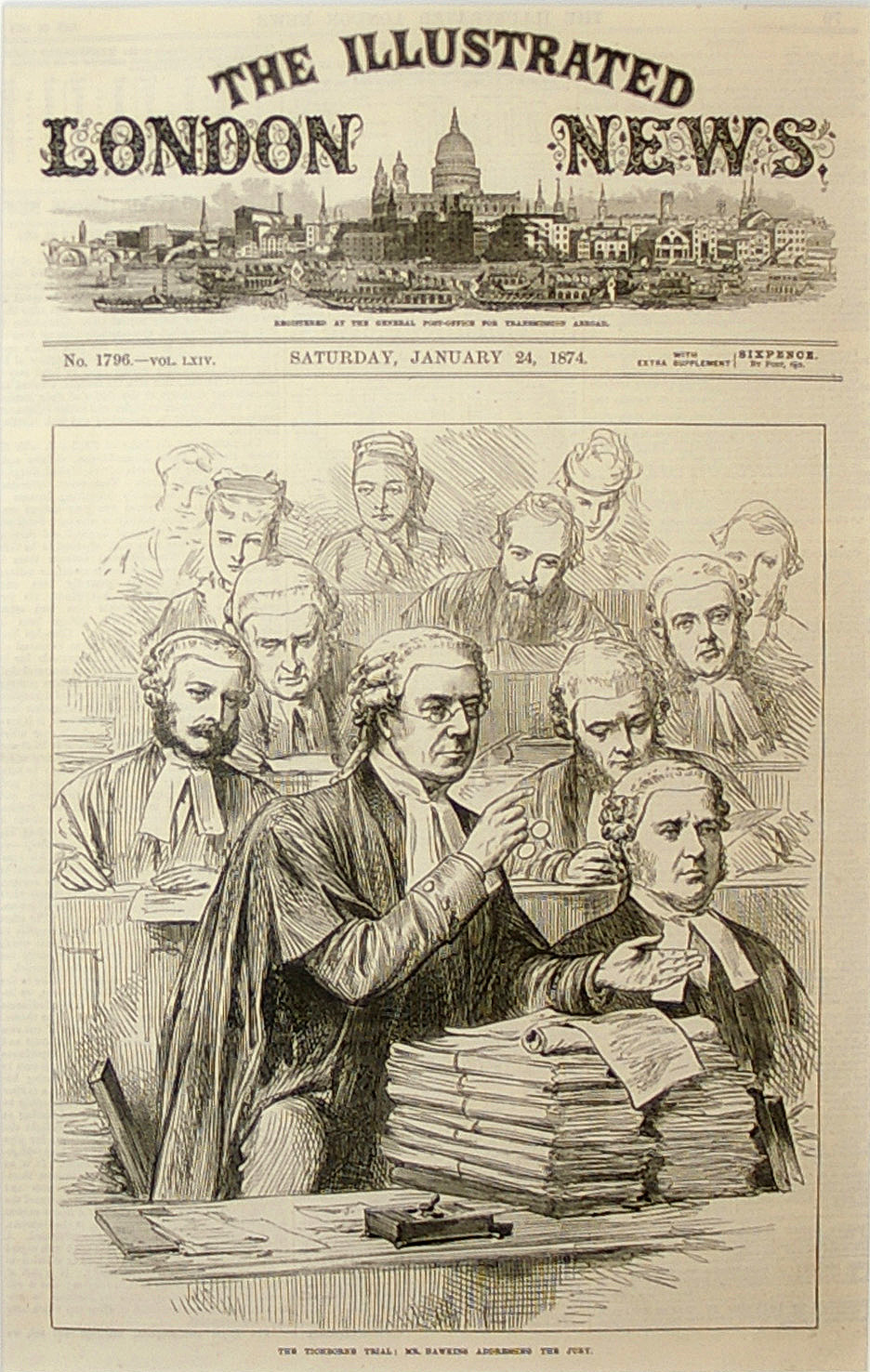

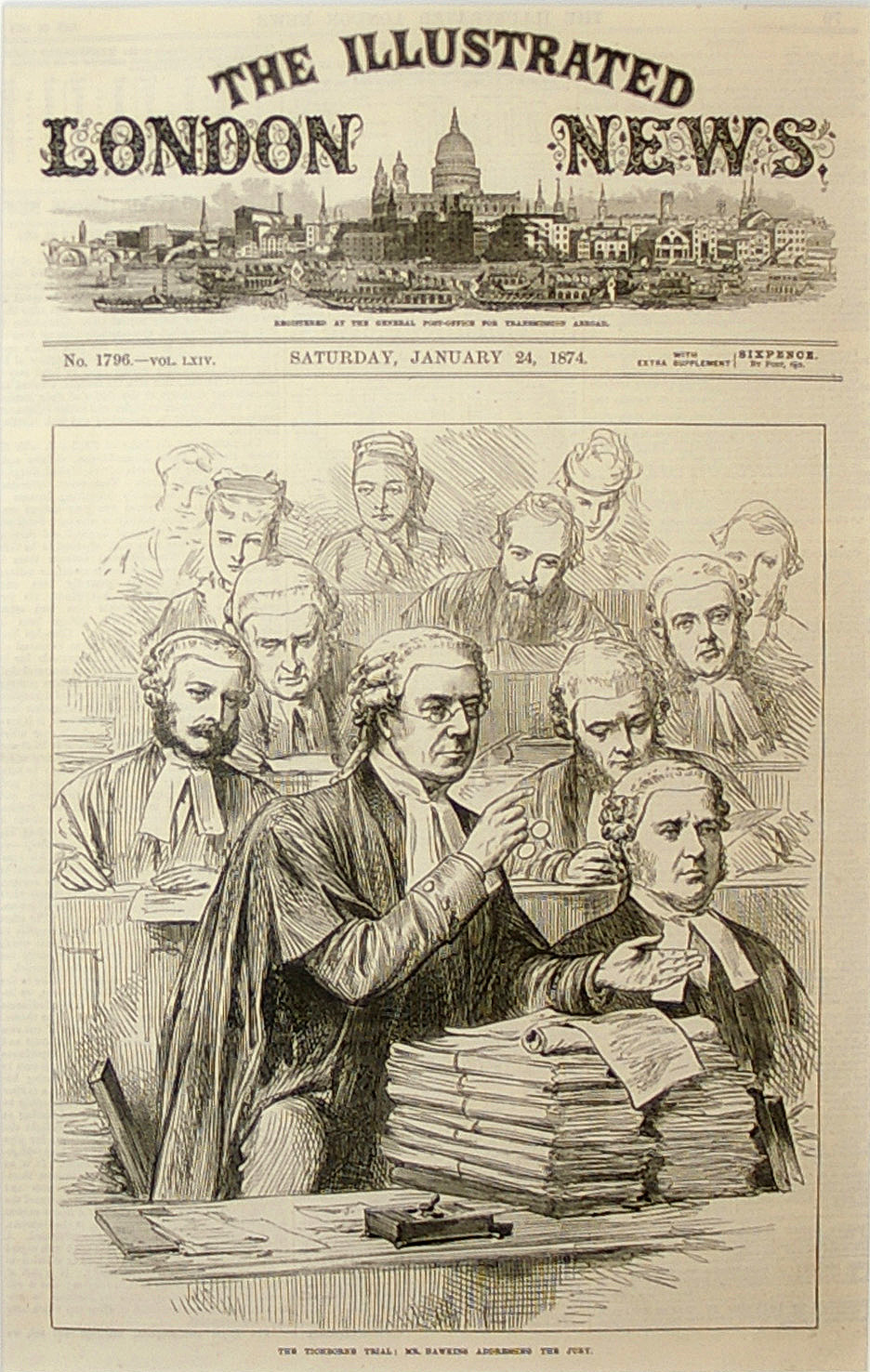

The trial, one of the lengthiest cases heard in an English court, began on 21 April 1873 and lasted until 28 February 1874, occupying 188 court days. The tone was dominated by Kenealy's confrontational style; his personal attacks extended not only to witnesses but to the Bench and led to frequent clashes with Cockburn. Under the legal rules that then applied to criminal cases, the Claimant, though present in court, was not allowed to testify. Away from the court he revelled in his celebrity status; the American writer

The trial, one of the lengthiest cases heard in an English court, began on 21 April 1873 and lasted until 28 February 1874, occupying 188 court days. The tone was dominated by Kenealy's confrontational style; his personal attacks extended not only to witnesses but to the Bench and led to frequent clashes with Cockburn. Under the legal rules that then applied to criminal cases, the Claimant, though present in court, was not allowed to testify. Away from the court he revelled in his celebrity status; the American writer Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

, who was then in London, attended an event at which the Claimant was present and "thought him a rather fine and stately figure". Twain observed that the company were "educated men, men moving in good society.... It was 'Sir Roger', always 'Sir Roger' on all hands, no one withheld the title".

Altogether, Hawkins called 215 witnesses, including numbers from France, Melipilla, Australia and Wapping, who testified either that the Claimant was not Roger Tichborne or that he was Arthur Orton. A handwriting expert swore that the Claimant's writing resembled Orton's but not Roger Tichborne's.McWilliam 2007, pp. 95–97 The entire story of rescue by the ''Osprey'' was, Hawkins asserted, a fraud. A ship of that name had arrived in Melbourne in July 1854 but did not correspond to the Claimant's description. Furthermore, the Claimant had provided the wrong name for ''Osprey''s captain, and the names he gave for two of ''Osprey''s crew were found to belong to members of the crew of the ''Middleton'', the ship which had landed Orton at Hobart. No mention of a rescue had been found in ''Osprey''s log or in the Melbourne harbourmaster's records. Giving evidence on the contents of the sealed packet, Gosford revealed that it contained information regarding the disposition of certain properties, but nothing relating to Katherine Doughty's seduction or pregnancy.

Kenealy's defence was that the Claimant was victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment. He frequently sought to demolish witnesses' character, as with Lord Bellew, whose reputation he destroyed by revealing details of the peer's adultery. Kenealy's own witnesses included Bogle and Biddulph, who remained steadfast, but more sensational testimony came from a sailor called Jean Luie, who claimed that he had been on the ''Osprey'' during the rescue mission. Luie identified the Claimant as "Mr Rogers", one of six survivors picked up and taken to Melbourne. On investigation Luie was found to be an impostor, a former prisoner who had been in England at the time of the ''Bellas sinking. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.

Kenealy's defence was that the Claimant was victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment. He frequently sought to demolish witnesses' character, as with Lord Bellew, whose reputation he destroyed by revealing details of the peer's adultery. Kenealy's own witnesses included Bogle and Biddulph, who remained steadfast, but more sensational testimony came from a sailor called Jean Luie, who claimed that he had been on the ''Osprey'' during the rescue mission. Luie identified the Claimant as "Mr Rogers", one of six survivors picked up and taken to Melbourne. On investigation Luie was found to be an impostor, a former prisoner who had been in England at the time of the ''Bellas sinking. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.

Summing-up, verdict and sentence

After closing addresses from Kenealy and Hawkins, Cockburn began summing-up on 29 January 1874. His speech was prefaced by a severe denunciation of Kenealy's conduct, "the longest, severest and best merited rebuke ever administered from the Bench to a member of the bar" according to the trial's chronicler John Morse. The tone of the summing-up was partisan, frequently drawing the jury's attention to the Claimant's "gross and astonishing ignorance" of things he would certainly know if he were Roger Tichborne.Morse, p. 78 Cockburn rejected the Claimant's version of the sealed package contents and all imputations against Katherine Doughty's honour. Of Cockburn's peroration, Morse remarked that "never was a more resolute determination manifested y a judgeto control the result". While much of the press applauded Cockburn's forthrightness, his summing-up was also criticised as "a Niagara of condemnation" rather than an impartial review. The jury retired at noon on Saturday 28 February, and returned to the court within 30 minutes. Their verdict declared that the Claimant was not Roger Tichborne, that he had not seduced Katherine Doughty, and that he was indeed Arthur Orton. He was thus convicted of perjury. The jury added a condemnation of Kenealy's conduct during the trial. After the judges refused his request to address the court, the Claimant was sentenced to two consecutive terms of seven years' imprisonment. Kenealy's behaviour ended his legal career; he was expelled from the Oxford circuit mess and fromGray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and W ...

, so that he could no longer practise. On 2 December 1874 the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

revoked Kenealy's patent as a Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister o ...

.

Aftermath

Popular movement

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the Claimant. He and Kenealy were hailed as heroes, the latter as a martyr who had sacrificed his legal career.

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the Claimant. He and Kenealy were hailed as heroes, the latter as a martyr who had sacrificed his legal career. George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, writing much later, highlighted the paradox whereby the Claimant was perceived simultaneously as a legitimate baronet and as a working-class man denied his legal rights by a ruling elite. In April 1874 Kenealy launched a political organisation, the "Magna Charta Association", with a broad agenda that reflected some of the Chartist demands of the 1830s and 1840s. In February 1875 Kenealy fought a parliamentary by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

for Stoke-upon-Trent

Stoke-upon-Trent, commonly called Stoke is one of the six towns that along with Hanley, Burslem, Fenton, Longton and Tunstall form the city of Stoke-on-Trent, in Staffordshire, England.

The town was incorporated as a municipal borough in 18 ...

as "The People's Candidate", and won with a resounding majority. However, he failed to persuade the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

to establish a royal commission into the Tichborne trial, his proposal securing only his own vote and the support of two non-voting tellers, against 433 opposed. Thereafter, within parliament Kenealy became a generally derided figure, and most of his campaigning was conducted elsewhere. In the years of the Tichborne movement's popularity a considerable market was created for souvenirs in the form of medallions, china figurines, teacloths and other memorabilia. However, by 1880 interest in the case had declined, and in the General Election of that year Kenealy was heavily defeated. He died of heart failure a few days after the election.McWilliam 2007, pp. 167–68 The Magna Charta Association continued for several more years, with dwindling support; ''The Englishman'', the newspaper founded by Kenealy during the trial, closed down in May 1886, and there is no evidence of the Association's continuing activities after that date.

Claimant's release and final years

The Claimant was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years.McWilliam 2007, pp. 183–85 He was much slimmer; a letter to Onslow dated May 1875 reports a loss of . Throughout his imprisonment he had maintained that he was Roger Tichborne, but on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with

The Claimant was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years.McWilliam 2007, pp. 183–85 He was much slimmer; a letter to Onslow dated May 1875 reports a loss of . Throughout his imprisonment he had maintained that he was Roger Tichborne, but on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Br ...

s and circuses. The British public's interest in him had largely waned; in 1886 he went to New York but failed to inspire any enthusiasm there and ended up working as a bartender.

He returned in 1887 to England, where, although not officially divorced from Mary Ann Bryant, he married a music hall singer, Lily Enever.McWilliam 2007, pp. 273–75 In 1895, for a fee of a few hundred pounds, he confessed in ''The People

The ''Sunday People'' is a British tabloid Sunday newspaper. It was founded as ''The People'' on 16 October 1881.

At one point owned by Odhams Press, The ''People'' was acquired along with Odhams by the Mirror Group in 1961, along with the ...

'' newspaper that he was, after all, Arthur Orton. With the proceeds he opened a small tobacconist's shop in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

; however, he quickly retracted the confession and insisted again that he was Roger Tichborne. His shop failed, as did other business attempts, and he died destitute, of heart disease, on 1 April 1898. His funeral caused a brief revival of interest; around 5,000 people attended Paddington cemetery for the burial in an unmarked pauper's grave. In what McWilliam calls "an act of extraordinary generosity" the Tichborne family allowed a card bearing the name "Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne" to be placed on the coffin before its interment. The name "Tichborne" was registered in the cemetery's records.

Appraisal

Commentators have generally accepted the trial jury's verdict that the Claimant was Arthur Orton. However, McWilliam cites the monumental study by Douglas Woodruff (1957), in which the author posits that the Claimant could just possibly have been Roger Tichborne. Woodruff's principal argument is the sheer improbability that anyone could conceive such an imposture from scratch, at such a distance, and then implement it: " was carrying effrontery beyond the bounds of sanity if Arthur Orton embarked with a wife and retinue and crossed the world, knowing that they would all be destitute if he did not succeed in convincing a woman he had never met and knew nothing about first-hand, that he was her son".Woodruff, pp. 452–53 In 1876, while the Claimant was serving his prison sentence, interest was briefly raised by the claims of William Cresswell, an inmate of a Sydney lunatic asylum, that he was Arthur Orton. There was circumstantial evidence that indicated some connection with Orton, and the Claimant's supporters campaigned to have Cresswell brought to England. Nothing came of this, although the question of Cresswell's possible identity remained a matter of dispute for years. In 1884 a Sydney court found the matter undecided, and ruled that the ''status quo'' should be maintained; Cresswell stayed in the asylum. Shortly before his death in 1904 he was visited by the contemporaneous Lady Tichborne, who found no physical resemblance to any member of the Tichborne family. Attempts have been made to reconcile some of the troubling uncertainties and contradictions within the case. To explain the degree of facial resemblance (which even Cockburn accepted) of the Claimant to the Tichborne family, Onslow suggested in ''The Englishman'' that Orton's mother, a woman named Mary Kent, was an illegitimate daughter of Sir Henry Tichborne, Roger Tichborne's grandfather. An alternative story has Mary Kent being seduced by James Tichborne, making Orton and Roger half-brothers. Other versions have Orton and Roger as companions in crime in Australia, with Orton killing Roger and assuming his identity. The Claimant's daughter by Mary Ann Bryant, Teresa Mary Agnes, maintained that her father confessed to her that he had killed Arthur Orton and thus could not disclose details of his Australian years. There is no direct evidence for any of these theories. Teresa continued to proclaim her identity as a Tichborne daughter, and in 1924 was imprisoned for making threats and demands for money to the family. Woodruff submits that the legal verdicts, although fair given the evidence before the courts, have not fully resolved the "great doubt" that Cockburn admitted hung over the case. Woodruff wrote in 1957: "Probably for ever, now, its key long since lost... a mystery remains".Woodruff, pp. 458–59 A 1998 article in ''The Catholic Herald

The ''Catholic Herald'' is a London-based Roman Catholic monthly newspaper and starting December 2014 a magazine, published in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and, formerly, the United States. It reports a total circulation of abo ...

'' suggested that DNA profiling

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's DNA characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic t ...

might resolve the mystery. The enigma has launched numerous retellings of the story in book and film, including the short story "Tom Castro, the Implausible Imposter" from Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, as well as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known b ...

's '' Universal History of Infamy'', and David Yates

David Yates (born 8 October 1963) is an English film director, producer and screenwriter, who has directed feature films, short films, and television productions. He is best known for directing the final four films in the ''Harry Potter'' ser ...

's 1998 film '' The Tichborne Claimant''. Thus, Woodruff concludes, "the man who lost himself still walks in history, with no other name than that which the common voice of his day accorded him: the Claimant".

See also

*Bhawal case

Bhawal Estate was the second largest zamindari in Bengal (in modern-day Bangladesh) until it was abolished according to ''East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950''.

History

In the late 17th century, Daulat Ghazi was the zamind ...

, dealing with a famous case of suspected impersonation in British India.

* "The Principal and the Pauper

"The Principal and the Pauper" is the second episode of the ninth season of the American animated television series ''The Simpsons''. It first aired on the Fox network in the United States on September 28, 1997. In the episode, Seymour Skinner ...

", an episode of ''The Simpsons

''The Simpsons'' is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The series is a satirical depiction of American life, epitomized by the Simpson family, which consists of Homer, Marge, Bart, ...

'' inspired by the Tichborne case.

References

Notes Citations Bibliography * * * Gilbert, Michael, ''The Claimant, the Tichborne Case Revisited'', ( Constable and Company, London, 1959), by the well-known British mystery writer. * * * * (First published in 1897 by The American Publishing Company, Hartford, Connecticut.) * *Borges, Jorge Luis