Thomas de Courtenay, 13th Earl of Devon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (3 May 1414 – 3 February 1458) was a nobleman from

Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (3 May 1414 – 3 February 1458) was a nobleman from

The new earl found the political situation in Devonshire increasingly stacked against his own interests as a coalition of the greater

The new earl found the political situation in Devonshire increasingly stacked against his own interests as a coalition of the greater

At some time after 1421, Thomas de Courtenay married

At some time after 1421, Thomas de Courtenay married

An effigy identified by tradition as "little choke-a-bone", Margaret Courtenay (d. 1512), an infant daughter of

An effigy identified by tradition as "little choke-a-bone", Margaret Courtenay (d. 1512), an infant daughter of

The Earls of Devon

Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Devon, Thomas de Courtenay, 13th Earl of Earls of Devon People of the Wars of the Roses 1414 births 1458 deaths

Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (3 May 1414 – 3 February 1458) was a nobleman from

Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (3 May 1414 – 3 February 1458) was a nobleman from South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of the counties of Bristol, Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly), Dorset, Devon, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Cities and ...

. His seat was at Colcombe Castle

Colcombe Castle was a castle or fortified house situated about a north of the town of Colyton, Devon, Colyton in East Devon.

It was a seat of the House of Courtenay, Courtenay family, Earl of Devon, Earls of Devon, whose principal seat was ...

near Colyton, and later at the principal historic family seat of Tiverton Castle

Tiverton Castle is the remains of a medieval castle dismantled after the Civil War and thereafter converted in the 17th century into a country house. It occupies a defensive position above the banks of the River Exe at Tiverton in Devon.

Desc ...

, after his mother's death. The Courtenay family

The House of Courtenay is a medieval noble house, with branches in France, England and the Holy Land. One branch of the Courtenays became a Royal House of the Capetian Dynasty, cousins of the Bourbons and the Valois, and achieved the title o ...

had historically been an important one in the region, and the dominant force in the counties of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

. However, the rise in power and influence of several gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

families and other political players, in the years leading up to Thomas' accession to the earldom, threatened the traditional dominance of the earls of Devon in the area. Much of his life was spent in armed territorial struggle against his near-neighbour, Sir William Bonville of Shute, at a time when central control over the provinces was weak. This feud forms part of the breakdown in law and order in England that led to the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

.

Courtenay was for a time engaged in overseas service during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

. Increasingly, however, his efforts became directed towards strengthening his position at home. He had been married off as an infant to Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

, placing Courtenay close to the English king's Beaufort Beaufort may refer to:

People and titles

* Beaufort (surname)

* House of Beaufort, English nobility

* Duke of Beaufort (England), a title in the peerage of England

* Duke of Beaufort (France), a title in the French nobility

Places Polar regions ...

kinsmen. Due to this connection, Courtenay started his career as an adherent to the English court's Beaufort Beaufort may refer to:

People and titles

* Beaufort (surname)

* House of Beaufort, English nobility

* Duke of Beaufort (England), a title in the peerage of England

* Duke of Beaufort (France), a title in the French nobility

Places Polar regions ...

party. Upon their demise in the late 1440s, he abandoned it in favour of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

. When York sought the support of Courtenay's arch-enemy Bonville, Courtenay fell out of favour with him. When the Wars of the Roses broke out, he was in the party of the queen, Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou (french: link=no, Marguerite; 23 March 1430 – 25 August 1482) was Queen of England and nominally Queen of France by marriage to King Henry VI from 1445 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471. Born in the Duchy of Lorrain ...

, and was one of the Lancastrian commanders at the First Battle of St Albans

The First Battle of St Albans, fought on 22 May 1455 at St Albans, 22 miles (35 km) north of London, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses in England. Richard, Duke of York, and his allies, the Neville earls of Salisb ...

, where he was wounded.

Courtenay was said to have promoted a reconciliation between the Lancastrian and Yorkist parties, but he died suddenly in 1458. The Wars of the Roses later led to the deaths and executions of all three of Courtenay's sons, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, Henry, and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, and to the eventual attainder

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditar ...

of his titles and forfeiture of his lands. The Earldom was however revived in 1485 for his distant cousin, Sir Edward Courtenay, third in descent from his great-uncle.

Youth

Courtenay was born on 3 May 1414, the only surviving son of Hugh Courtenay, 4th/12th Earl of Devon (1389 – 16 June 1422) and Anne Talbot (c.1393–1441), sister of the renowned warriorJohn Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

. He succeeded as Earl of Devon in 1422, at the age of eight. He may at some time before have become a ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

of the all-powerful Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter (c. January 137731 December 1426) was an English military commander during the Hundred Years' War, and briefly Chancellor of England. He was the third of the four children born to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, ...

.

According to Cokayne, Courtenay was knighted on 19 May 1426 by King Henry VI of England

Henry VI (6 December 1421 – 21 May 1471) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. The only child of Henry V, he succeeded to the English thron ...

, and on 16 December 1431, Courtenay was among an entourage of 300 who attended King Henry VI's second coronation at Notre Dame in Paris.

Majority

It appears that no inquisition of proof of age, customary for atenant in chief

In medieval and early modern Europe, the term ''tenant-in-chief'' (or ''vassal-in-chief'') denoted a person who held his lands under various forms of feudal land tenure directly from the king or territorial prince to whom he did homage, as oppos ...

, was taken for his father. Based on his family's history and standing and on his own position as the leading landowner of the county, probably expected to take his place as the leader of Devon society. However, his mother's longevity meant that her dower portion, including Tiverton Castle, and the other Courtenay estates which had been alienated under his father's will were not in his hands and the young Courtenay was forced to live at Colcombe Castle, near Colyton, very close to his enemy William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville

William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville (12 or 31 August 1392 – 18 February 1461), was an English nobleman and an important, powerful landowner in south-west England during the Late Middle Ages. Bonville's father died before Bonville reached ...

, at Shute. His income of £1500 p.a. was lower than that of most nobles of comparable rank.

Career

Struggle with Bonville

The new earl found the political situation in Devonshire increasingly stacked against his own interests as a coalition of the greater

The new earl found the political situation in Devonshire increasingly stacked against his own interests as a coalition of the greater gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

, led by William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville

William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville (12 or 31 August 1392 – 18 February 1461), was an English nobleman and an important, powerful landowner in south-west England during the Late Middle Ages. Bonville's father died before Bonville reached ...

, and the earl's cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham, threatened the Courtenays' traditional dominance of the county. The relationship was complicated by Bonville's second marriage in 1430 to Elizabeth Courtenay (d. 1471), Courtenay's aunt. Despite links via his wife, Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

, to the ascendant "court party" led by Cardinal Beaufort

Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester, was an English prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398) then Bishop of Winchester (1404) and was from 1426 a Cardinal of the Church of Ro ...

and John Beaufort, 1st earl of Somerset and Marquess of Dorset, and by Margaret Holland

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

, daughter of the Earl of Kent

The peerage title Earl of Kent has been created eight times in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In fiction, the Earl of Kent is also known as a prominent supporting character in William Shakespeare's tragedy K ...

, Courtenay failed to rectify his situation and instead resorted to violence, beginning in 1439. With the decline of Beaufort power, Courtenay became increasingly associated with Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

. Courtenay had been attacking Bonville's estates in the summer of 1439 and the king despatched a Privy Councillor

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, Sir John Stourton, 1st Baron Stourton

John Stourton, 1st Baron Stourton (19 May 1400 – 25 November 1462) of Stourton, Wiltshire, was an English soldier and politician, elevated to the peerage in 1448.

Origins

He was born on 19 May 1400 at Witham Friary, Somerset, the son of Sir ...

, to extract a promise of good behaviour from Courtenay, who was thereafter reluctant to attend the court in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. In 1441, Courtenay was appointed as Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall ( kw, Duketh Kernow) is one of two royal duchies in England, the other being the Duchy of Lancaster. The eldest son of the reigning British monarch obtains possession of the duchy and the title of 'Duke of Cornwall' at ...

, a nearly identical post to Royal Steward for Cornwall which had been granted to Sir William Bonville in 1437, for life. A week later in May 1441, the warrant was retracted. Disputes arose between the two which contemporary records portray as reaching the status of a private war

A feud , referred to in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, or private war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one par ...

. Two men wearing Courtenay livery attacked Sir Philip Chetwynd, a friend of Bonville, on the road to London, apparent evidence that the Council's arbitration of November 1440 had failed. Courtenay and Bonville were summoned before the King in December 1441, and were publicly reconciled. Tensions remained however and this may have been a factor in the crown's requests to both Courtenay, who initially refused, and Bonville to serve in France, Bonville as seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

of Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

from 1442–46 and Courtenay at Pont-l'Évêque in Normandy in 1446. This is one of the few times that Courtenay served abroad, for he had refused in March 1443, seemingly preferring to spend his time bolstering his position in Devon or at court. While Bonville was abroad, the King released Devon from his debts, including the recognisance

In some common law nations, a recognizance is a conditional pledge of money undertaken by a person before a court which, if the person defaults, the person or their sureties will forfeit that sum. It is an obligation of record, entered into before ...

for good behaviour, probably remitted by the influence of father-in-law, John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset.

Royal appointments

Commissions

His advantageous marriage toMargaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

brought him links to the "court party", and Courtenay began to be selected by the king to serve on Westcountry commissions and was granted an annuity of £100 for his services.

Other

1445 marked a fleeting high point in Courtenay's fortunes, with his appointment as High Steward of England at Queen Margaret's coronation on 25 May. Only the year before, March 1444, Bonville had identified himself with Suffolk, at Margaret's betrothal in Rouen.Abandonment of Beauforts

The deaths of his brother-in-lawJohn Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, 3rd Earl of Somerset, KG (25 March 1404 – 30 May 1444) was an English nobleman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He was the maternal grandfather of Henry VII.

Origins

Born on 25 ...

, in 1444, and of the leader of the party Cardinal Beaufort

Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester, was an English prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398) then Bishop of Winchester (1404) and was from 1426 a Cardinal of the Church of Ro ...

, 2nd son of John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, in 1447, removed Beaufort leadership of the 'court' party, leaving William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, (16 October 1396 – 2 May 1450), nicknamed Jackanapes, was an English magnate, statesman, and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He became a favourite of the weak king Henry VI of Engla ...

, as the most influential figure in national politics. While there is no evidence of direct antagonism between Courtenay and the Duke of Suffolk, the latter appeared to favour the Bonvilles. Sir William Bonville enjoyed links with Suffolk and married his daughter to William Tailboys

William Tailboys, de jure 7th Baron Kyme (c.1416 – 26 May 1464) was a wealthy Lincolnshire squire and adherent of the House of Lancaster, Lancastrian cause during the Wars of the Roses.

He was born in Kyme, Lincolnshire, the son of Sir Walter ...

, one of the Duke's closest associates. Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of this favour was Bonville's elevation to the peerage, presumably at the direction of Suffolk, as Baron Bonville

The title of Baron Bonville was created once in the Peerage of England. On 10 March 1449, Sir William Bonville II was summoned to Parliament. On his death in 1461, the barony was inherited by his great-granddaughter Cecily Bonville, who two mont ...

of Chewton Mendip in 1449.

Switch to Yorkist party

This promotion of his enemy Bonville may have prompted Devon to oppose the 'Court party' and to serve with his friendRichard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

during Jack Cade's Rebellion

Jack Cade's Rebellion was a popular revolt in 1450 against the government of England, which took place in the south-east of the country between the months of April and July. It stemmed from local grievances regarding the corruption, maladmini ...

. Courtenay switched allegiance to York, who with the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

took control briefly of London. He remained loyal to York during the Parliament of November 1450, when they invoked the support of the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

to raise taxation. Having rescued the Duke of Somerset

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

from an angry London mob, York himself had to flee, taking refuge on the Earl of Devon's barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

rowing down the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

. It is hardly surprising that Devon began to become associated with York, who had assumed the leadership of the "opposition" party. The parlous state of national politics (whether the king was a vindictive factionalist or an inane non-entity is largely irrelevant in this context) combined with what seems like a reckless and violent element in Courtenay's own character, led to a further campaign of violence against Bonville and the Suffolk-aligned James Butler, 5th Earl of Ormond and Earl of Wiltshire. Courtenay and his troops attempted to capture Butler near Bath in Wiltshire before returning to besiege Bonville in Taunton Castle

Taunton Castle is a castle built to defend the town of Taunton, Somerset, England. It has origins in the Anglo Saxon period and was later the site of a priory. The Normans then built a stone structured castle, which belonged to the Bishops of ...

. The arrival of York (whether to suppress or aid the disturbances is uncertain) caused the two sides to make peace which, unsurprisingly, had no real meaning. York then embarked on his abortive attempt to take control of the royal government by force, his only allies being Courtenay and his sometime-associate, Edward Brooke, 6th Baron Cobham

Edward Brooke, 6th Baron Cobham (c. 14156 June 1464), lord of the Manor of Cobham, Kent, was an English peer.

Biography

His parents were Sir Thomas Brooke and wife Joan Braybroke, 5th Baroness Cobham.

He was a member of parliament for Somerset ...

.

In the West Country, Courtenay hounded Bonville without mercy, and pursued him to Taunton Castle

Taunton Castle is a castle built to defend the town of Taunton, Somerset, England. It has origins in the Anglo Saxon period and was later the site of a priory. The Normans then built a stone structured castle, which belonged to the Bishops of ...

and laid siege to it. York arrived to lift the siege, and imprisoned Bonville, who was nevertheless quickly released. This exploit ended with the disgrace of all three 'Yorkists' and their submission to royal mercy in March. The King had issued an arrest warrant on 24 September 1451, drafted by Somerset, to be enforced by Butler and Bonville. The Yorkist rebellions prompted royal commissions for Buckingham and Bonville on 14 February 1452. A direct summons without delay was ordered by Royal Proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

on 17 February to bring Courtenay and Lord Cobham to London.

Treason charge

Courtenay was charged withtreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and briefly imprisoned in Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

, before appearing on trial before the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

. His disgrace

''Disgrace'' is a novel by J. M. Coetzee, published in 1999. It won the Booker Prize. The writer was also awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature four years after its publication.

Plot

David Lurie is a white South African professor of English wh ...

and political isolation allowed his Devonshire rivals to consolidate their positions, further undermining his decreased standing in the county. Bonville acquired all royal commissions in the south-west.

Resurgence of York

King Henry VI's madness and York's appointment as Protector in 1453/4 resulted in a partial rally in Courtenay's fortunes, including his re-appointment to commissions of the peace in the south-western counties, the key barometer of the local balance of power. He was a member of the Royal Council until April 1454. Courtenay was bound over to keep the peace with a fine of 1000 marks, but ignored its restrictions. Threatened by the Council on 3 June, he was forced on 24 July to make a new bond.Abandonment by York

This was, however, the end of Courtenay's links with York, whose increasingly tight links with the Neville earls ofSalisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

and Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

led to an alignment with Bonville away from Courtenay. This culminated in the marriage of William Bonville, 6th Baron Harington

William Bonville, 6th Baron Harington (1442 – 30 December 1460) was an English nobleman who was a loyal adherent of the House of York during the dynastic conflict in England in the 15th century now known as the Wars of the Roses. He was slain ...

, Bonville's grandson, to Salisbury's daughter, Katherine. Courtenay did not endear himself to Somerset either, as he and his sons repeatedly disrupted the sessions of the commissioners of the peace in Exeter during 1454/5, which did not assist Protector Somerset in promoting his role as the guardian of law and order. Courtenay was present at the First Battle of St Albans

The First Battle of St Albans, fought on 22 May 1455 at St Albans, 22 miles (35 km) north of London, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses in England. Richard, Duke of York, and his allies, the Neville earls of Salisb ...

, and was wounded. York however still considered him at least neutral as the Duke's letters addressed to the King on the eve of battle were delivered to the king via the apparently still trusted hands of Courtenay.

Final assault on Bonville

Perhaps inspired by the way the Nevilles and York had forcefully ended their respective feuds with the Percies and theDuke of Somerset

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

in the battle, Courtenay returned to Devon and commenced a further campaign of violence against Bonville and his allies, who were now attached to Warwick's party. The violence began in October 1455 with the horrific murder by Courtenay allies of Nicholas Radford, an eminent Westcountry

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Gloucesters ...

lawyer, Recorder of Exeter and one of Bonville's councillors. Several contemporary accounts, including the Paston Letters

The ''Paston Letters'' is a collection of correspondence between members of the Paston family of Norfolk gentry and others connected with them in England between the years 1422 and 1509. The collection also includes state papers and other impor ...

, record this event with the ensuing mock-funeral and coronary inquest accompanied by the singing of highly inappropriate songs, in tones of shock and horror unusual during the blunted sensitivities of the fifteenth century. Among the murderers was Thomas Courtenay, the earl's son and later successor. Parliament, meeting in November 1455, reported 800 horsemen and 4,000 infantry running amok across Devon. On 3 November 1455 Courtenay with his sons, Thomas Carrew of Ashwater and a considerable force of 1,000 men occupied the city of Exeter, nominally controlled by Bonville as castellan of the royal castle of Exeter, which they continued to control until 23 December 1455. Courtenay had before warned the populace that Bonville was approaching with a 'great multitude' to sack the city. On 3 November 1455 Bonville's men setting out from his seat at Shute had looted the Earl's nearby house at Colcombe Castle

Colcombe Castle was a castle or fortified house situated about a north of the town of Colyton, Devon, Colyton in East Devon.

It was a seat of the House of Courtenay, Courtenay family, Earl of Devon, Earls of Devon, whose principal seat was ...

, Colyton, and Bonville promised his support to the Earl's distant cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham. Dozens of men violated consecrated ground and Radford's valuables were extracted from the cathedral and his house in Exeter was also robbed. Village-dwellers with Bonville connections were assaulted by Devon's men. Powderham Castle

Powderham Castle is a fortified manor house situated within the parish and former manor of Powderham, within the former hundred of Exminster, Devon, about south of the city of Exeter and mile (0.4 km) north-east of the village of ...

, home to the earl's estranged cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay (d. 1463), an ally of Bonville, was besieged on 15 November 1455, the earl's weaponry now including a serpentine cannon. Bonville attempted to relieve the castle but was repulsed as the Earl threatened to batter down its walls. Finally battle was joined directly between Bonville and Courtenay at the Battle of Clyst Heath, at Clyst Bridge, just southeast of Exeter on 15 December 1455. While it seems that Bonville was put to flight, the number of dead or wounded is entirely unknown. Two days later Thomas Carrew with 500 of Courtenay's retainers pillaged Shute, seizing a bounty of looted goods. Courtenay and his men left Exeter on 21 December 1455 and shortly afterwards submitted to York at Shaftesbury

Shaftesbury () is a town and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is situated on the A30 road, west of Salisbury, near the border with Wiltshire. It is the only significant hilltop settlement in Dorset, being built about above sea level on a ...

in Dorset. Early in December 1455, the King had dismissed Devon from the Commission of Peace, and citizens of Exeter had been instructed not to help his army of "misrule" in any way.

Aftermath of Clyst Heath

Devon was incarcerated in the Tower. Originally, the government planned to bring him to trial for treason but this was abandoned once King Henry VI returned to sanity in February 1456, and York was removed as Protector. Courtenay was also returned to the commission of the peace for Devonshire, seemingly the work of Queen Margaret of Anjou who had taken personal control of the court. Courtenay had cultivated links with Queen Margaret, and an alliance was sealed by the marriage of his son and heir, Sir Thomas Courtenay, to the Queen's kinswoman, Marie, the daughter ofCharles, Count of Maine

Charles du Maine (1414–1472) was a French prince of blood and an advisor to Charles VII of France, his brother-in-law, during the Hundred Years' War. He was the third son of Louis II, Duke of Anjou and King of Naples, and Yolande of Aragon.

...

. Despite having been banned from entering and leading armed men into Exeter and holding assemblies, 500 men under John Courtenay entered the High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

on 8 April 1456. His rivals, Philip Courtenay and Lord Fitzwarin, were prevented from exercising commissions as Justices of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, and were forced to leave the city. Butler, Bonville's patron, and Sir John Fortescue, Chief Justice, arrived with a large entourage to investigate under a commission of oyer et terminer. They rejected Courtenay's petition to have Bonville's sheriffdom of Devon removed. Two years later his sons, Thomas and Henry Courtenay, were absolved of the murder of Nicholas Radford.

Courtenay was restored to the bench of JPs and was made Keeper of the Park of Clarendon in February 1457, and Keeper of Clarendon Forest in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

on 17 July 1457.

Marriage and issue

Lady Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

, daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset and 1st Marquess of Dorset, later only 1st Earl of Somerset, (c. 1373 – 16 March 1410) was an English nobleman and politician. He was the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt ...

(the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

(son of King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

) by his mistress, Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (born Katherine de Roet, – 10 May 1403), also spelled Katharine or Catherine, was the third wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the fourth (but third surviving) son of King Edward III.

Daughter o ...

, later his wife) by his wife, Lady Margaret Holland

The word ''lady'' is a term for a girl or woman, with various connotations. Once used to describe only women of a high social class or status, the equivalent of lord, now it may refer to any adult woman, as gentleman can be used for men. Inform ...

. Margaret was thus the sister of Henry Beaufort, 2nd Earl of Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 2nd Earl of Somerset (''probably'' 26 November 1401 – 25 November 1418) was an English nobleman who died aged 17 at the Siege of Rouen in France during the Hundred Years' War, fighting for the Lancastrian cause. As he died unma ...

, of John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, 3rd Earl of Somerset, KG (25 March 1404 – 30 May 1444) was an English nobleman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He was the maternal grandfather of Henry VII.

Origins

Born on 25 ...

, of Thomas Beaufort, Count of Perche

Thomas Beaufort, styled 1st Count of Perche (c. 1405 – 3 October 1431) was a member of the Beaufort family and an English commander during the Hundred Years' War.

He was the third son of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset and his wife, Margaret ...

, of Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scotland

Joan Beaufort ( 1404 – 15 July 1445) was Queen of Scotland from 1424 to 1437 as the spouse of King James I of Scotland. During part of the minority of her son James II (from 1437 to 1439), she served as the regent of Scotland.

Background a ...

, and of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, 4th Earl of Somerset, 1st Earl of Dorset, 1st Marquess of Dorset styled 1st Count of Mortain, KG (140622 May 1455), was an English nobleman and an important figure during the Hundred Years' War. His riva ...

. Thomas and Margaret had three sons and six daughters:

*Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon

Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (1432 – 3 April 1461), was the eldest son of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon, by his wife Margaret Beaufort, the daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, and Margaret Holland, daughter ...

(1432 – 3 April 1461), was taken prisoner at the Battle of Towton

The Battle of Towton took place on 29 March 1461 during the Wars of the Roses, near Towton in North Yorkshire, and "has the dubious distinction of being probably the largest and bloodiest battle on English soil". Fought for ten hours between a ...

, and beheaded at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

on 3 April 1461, when the earldom was forfeited.

*Sir Henry Courtenay (d. 1467/9), Esquire, of West Coker

West Coker is a large village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated south west of Yeovil in the South Somerset district.

History

The name Coker comes from Coker Water ("crooked stream" from the Celtic ''Kukro'').

Artifacts from early ...

, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, beheaded for treason in the market place at Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

on 17 January 1469 (or 4 March 1467). As the earldom had been forfeited following the execution of his elder brother in 1461, he is not generally considered to have inherited from him the title "Earl of Devon", although for example Debrett's Peerage

Debrett's () is a British professional coaching company, publisher and authority on etiquette and behaviour, founded in 1769 with the publication of the first edition of ''The New Peerage''. The company takes its name from its founder, John Deb ...

, 1968, gives him as the 7th Earl and successor to his brother.

* John Courtenay, 7th/15th Earl of Devon (1435 – 3 May 1471), was restored to the earldom in 1470 by the Lancastrians in exile, and later slain at the Battle of Tewkesbury

The Battle of Tewkesbury, which took place on 4 May 1471, was one of the decisive battles of the Wars of the Roses in England. King Edward IV and his forces loyal to the House of York completely defeated those of the rival House of Lancaster ...

on 4 May 1471.

*Joan Courtenay (born c. 1441), who married firstly, Sir Roger Clifford, second son of Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford

Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford, also 8th Lord of Skipton (25 March 1414 – 22 May 1455), was the elder son of John, 7th Baron de Clifford, and Elizabeth Percy, daughter of Henry "Hotspur" Percy and Elizabeth Mortimer.

Family

Thomas ...

, who was beheaded after the Battle of Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

in 1485. She married secondly, Sir William Knyvet of Buckenham, Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

.

*Elizabeth Courtenay (born c. 1449), who married, before March 1490, Sir Hugh Conway.

*Anne Courtenay.

*Eleanor Courtenay.

*Maud Courtenay.

*Agnes Courtenay (1452 – 7 January 1485), who married Richard Saunders (1452-1480) of Charlwood

Charlwood is a village and civil parish in the Mole Valley district of Surrey, England. It is immediately northwest of London Gatwick Airport in West Sussex, close west of Horley and north of Crawley. The Historic counties of England, historic co ...

, Surrey.

Monument to Margaret Beaufort

William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon

William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475 – 9 June 1511), feudal baron of Okehampton and feudal baron of Plympton, was a member of the leading noble family of Devon. His principal seat was Tiverton Castle, Devon with further residences at ...

(1475–1511) by his wife Princess Catherine of York (d. 1527), the sixth daughter of King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

(1461–1483) exists in Colyton Church in Devon. The Courtenay residence of Colcombe Castle

Colcombe Castle was a castle or fortified house situated about a north of the town of Colyton, Devon, Colyton in East Devon.

It was a seat of the House of Courtenay, Courtenay family, Earl of Devon, Earls of Devon, whose principal seat was ...

was in the parish of Colyton. However, modern authorities have suggested, on the basis of the monument's heraldry, the effigy to be Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409–1449), the wife of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458).

The effigy is only about 3 ft in length, much smaller than usual for an adult. The face and head were renewed in 1907, and are said to have been based on the sculptor's own infant daughter. A 19th-century brass tablet above is inscribed: ''"Margaret, daughter of William Courtenay Earl of Devon and the Princess Katharine youngest daughter of Edward IVth King of England, died at Colcombe choked by a fish-bone AD MDXII and was buried under the window in the north transept of this church"''.

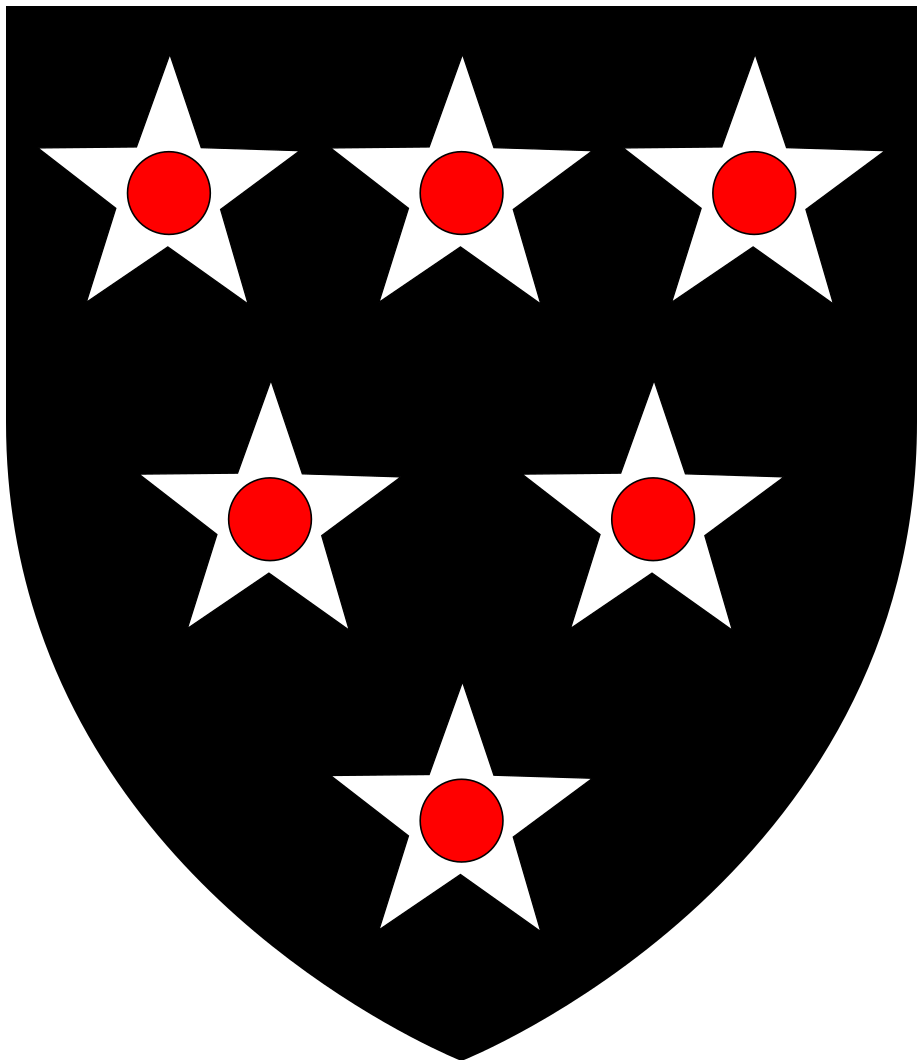

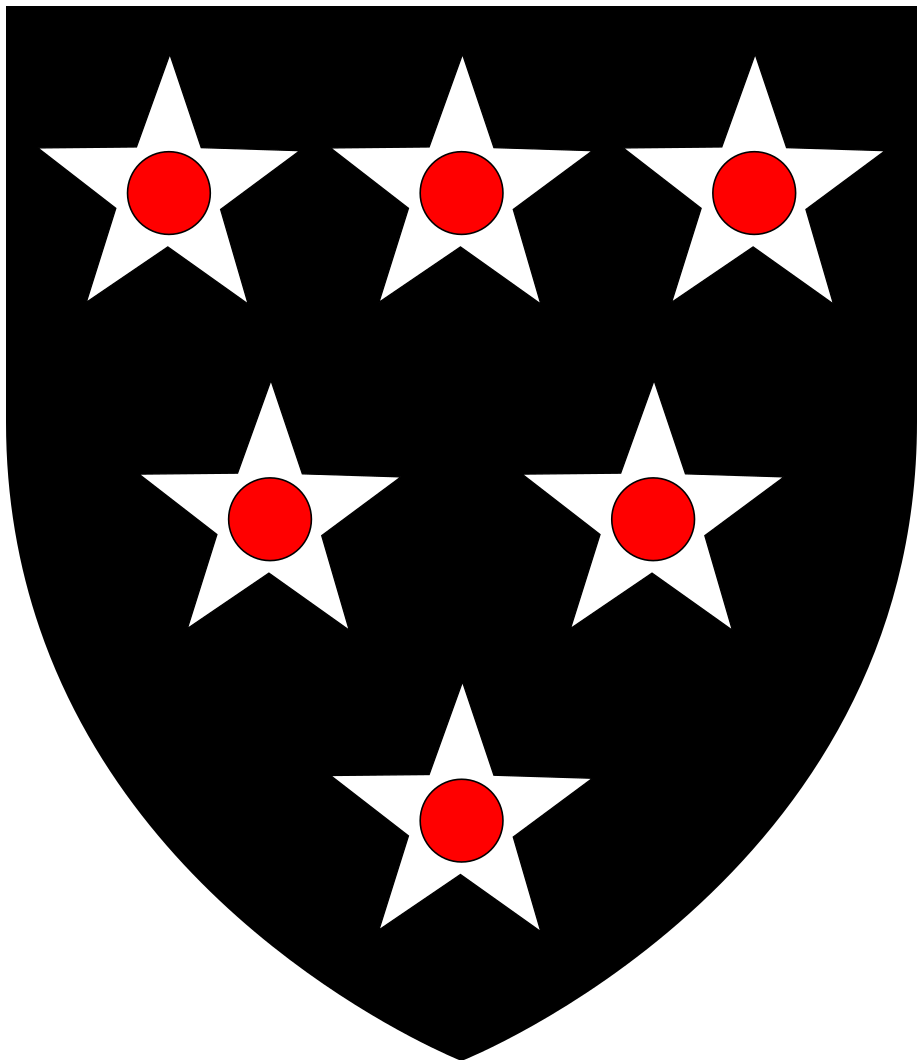

Heraldry

Three sculpted heraldic shields of arms exist above the effigy, showing the arms of Courtenay, Courtenayimpaling

Impalement, as a method of torture and execution, is the penetration of a human by an object such as a stake, pole, spear, or hook, often by the complete or partial perforation of the torso. It was particularly used in response to "crimes aga ...

the royal arms of England

The royal arms of England are the Coat of arms, arms first adopted in a fixed form at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1200) as Armorial of the House of Plantagenet, personal arms by the House of Plantagenet, Plantagenet kings who ruled ...

and the royal arms of England. Later authorities have suggested, on the basis of the monument's heraldry, the effigy to be the wife of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458), namely Lady Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409–1449), daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset, 1st Marquess of Dorset (1373–1410), KG, (later only 1st Earl of Somerset), (the first of the four illegitimate child

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

ren of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

(4th son of King Edward III), and his mistress Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (born Katherine de Roet, – 10 May 1403), also spelled Katharine or Catherine, was the third wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the fourth (but third surviving) son of King Edward III.

Daughter o ...

, later his wife) by his wife Margaret Holland

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

. The basis of this re-attribution is the supposed fact that the "royal arms" shown are not the arms of King Edward IV, but rather the arms of Beaufort. The arms of Beaufort are the royal arms of England differenced ''within a bordure

In heraldry, a bordure is a band of contrasting tincture forming a border around the edge of a shield, traditionally one-sixth as wide as the shield itself. It is sometimes reckoned as an ordinary and sometimes as a subordinary.

A bordure encl ...

compony argent and azure''.: "The effigy of this granddaughter of John of Gaunt, with the shields of Courtenay and Beaufort" (...). The relief sculpture does indeed show a border, albeit a thin one and not compony, around the royal arms, with such border omitted from the Courtenay arms.

Death

Courtenay received a summons to appear withYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

before the King in London at the Loveday Award. He broke his journey at Abingdon Abbey

Abingdon Abbey ( '' " St Mary's Abbey " '' ) was a Benedictine monastery located in the centre of Abingdon-on-Thames beside the River Thames.

The abbey was founded c.675 AD in honour of The Virgin Mary.

The Domesday Book of 1086 informs ...

, and died there on 3 February 1458. A contemporary chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

r asserted that he had been poisoned by the Prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

on the Queen's orders, which is perhaps unlikely considering the Earl's alliance with the Queen. In his will, the Earl requested burial in the Courtenay Chantry Chapel

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

of Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral, properly known as the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter, is an Anglican cathedral, and the seat of the Bishop of Exeter, in the city of Exeter, Devon, in South West England. The present building was complete by about 140 ...

. The will was proved at Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

on 21 February 1458, and an inquisition post mortem An Inquisition post mortem (abbreviated to Inq.p.m. or i.p.m., and formerly known as an escheat) (Latin, meaning "(inquisition) after death") is an English medieval or early modern record of the death, estate and heir of one of the king's tenants-in ...

was taken in 1467.

The Earl was succeeded by his eldest son, Thomas Courtenay, 14th Earl of Devon

Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (1432 – 3 April 1461), was the eldest son of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon, by his wife Margaret Beaufort, the daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, and Margaret Holland, daughte ...

, who was beheaded at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

on 3 April 1461 after the Battle of Towton

The Battle of Towton took place on 29 March 1461 during the Wars of the Roses, near Towton in North Yorkshire, and "has the dubious distinction of being probably the largest and bloodiest battle on English soil". Fought for ten hours between a ...

, and attainted by Parliament in November 1461, whereby the earldom was forfeited.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Selected reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Earls of Devon

Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Devon, Thomas de Courtenay, 13th Earl of Earls of Devon People of the Wars of the Roses 1414 births 1458 deaths

Thomas de Courtenay, 13th Earl of Devon

Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (3 May 1414 – 3 February 1458) was a nobleman from South West England. His seat was at Colcombe Castle near Colyton, Devon, Colyton, and later at the principal historic family seat of Tiverton Castle ...