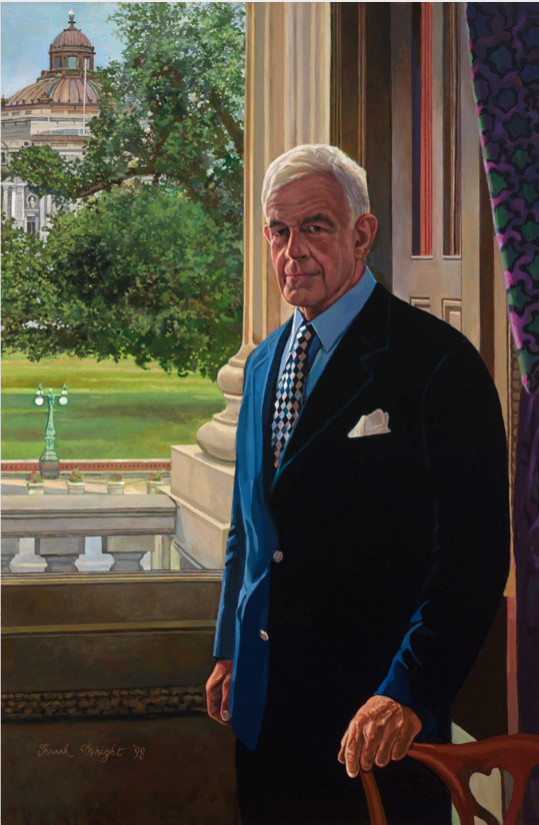

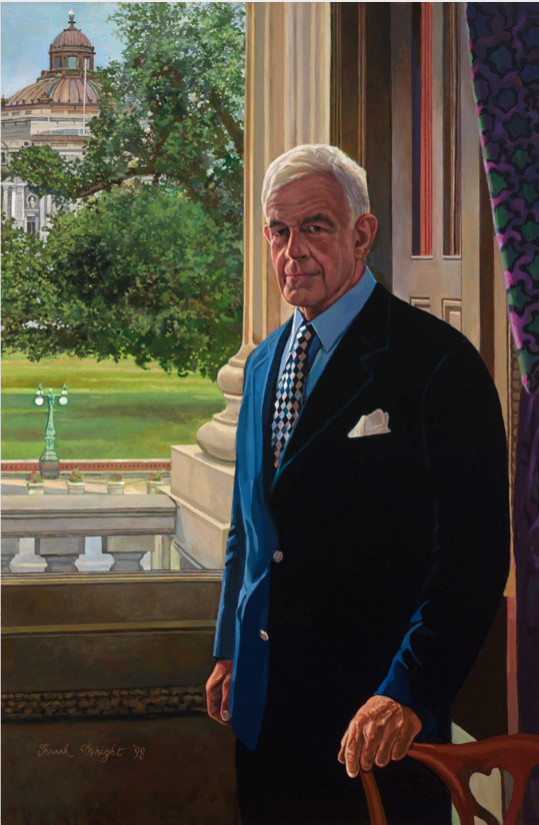

Thomas S. Foley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Stephen Foley (March 6, 1929 – October 18, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1989 to 1995. A member of the

Thomas Stephen Foley (March 6, 1929 – October 18, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1989 to 1995. A member of the

Foley, bio notes

/ref>

Thomas Stephen Foley (March 6, 1929 – October 18, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1989 to 1995. A member of the

Thomas Stephen Foley (March 6, 1929 – October 18, 2013) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1989 to 1995. A member of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, Foley represented Washington's fifth district for thirty years He was the first Speaker of the House since Galusha Grow

Galusha Aaron Grow (August 31, 1823 – March 31, 1907) was an American politician, lawyer, writer and businessman, who served as 24th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1861 to 1863. Elected as a Democrat in the 1850 congression ...

in 1862 to be defeated in a re-election campaign.

Born in Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the Cana ...

, Foley attended Gonzaga University

Gonzaga University (GU) () is a private Jesuit university in Spokane, Washington. It is accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. Founded in 1887 by Joseph Cataldo, an Italian-born priest and Jesuit missionary, the ...

and pursued a legal career, after graduating from the University of Washington School of Law

The University of Washington School of Law is the law school of the University of Washington, located on the northwest corner of the main campus in Seattle, Washington.

The 2023 '' U.S. News & World Report'' law school rankings place Wash ...

in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

. He joined the staff of Senator Henry M. Jackson

Henry Martin "Scoop" Jackson (May 31, 1912 – September 1, 1983) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a U.S. representative (1941–1953) and U.S. senator (1953–1983) from the state of Washington. A Cold War liberal and a ...

, after working as a prosecutor and an assistant attorney general. With Jackson's support, Foley won election to the House of Representatives, defeating incumbent Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Congressman Walt Horan. He served as Majority Whip from 1981 to 1987, and as Majority Leader from 1987 to 1989. After the resignation of Jim Wright, Foley became Speaker of the House.

Foley's district had become increasingly conservative during his tenure, but he won re-election throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. In the 1994

File:1994 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 1994 Winter Olympics are held in Lillehammer, Norway; The Kaiser Permanente building after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; A model of the MS Estonia, which sank in the Baltic Sea; Nelson ...

election, Foley faced attorney George Nethercutt

George Rector Nethercutt Jr. (born October 7, 1944) is an American lawyer, author, and politician. Nethercutt is the founder and chairman of The George Nethercutt Foundation. He was a Republican member of the United States House of Representative ...

. Nethercutt mobilized popular anger over Foley's opposition to term limits to defeat the incumbent Speaker. After leaving the House, Foley served as the United States Ambassador to Japan

The is the ambassador from the United States of America to Japan.

History

Since the opening of Japan by Commodore Matthew C. Perry, in 1854, the U.S. has maintained diplomatic relations with Japan, except for the ten-year period between the ...

from 1997 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

.

Early life, education, and legal career

Born and raised inSpokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the Cana ...

, Foley was the son of Helen Marie (née Higgins), a school teacher, and Ralph E. Foley a Superior Court judge for 34 years. He was of Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

descent on both sides of his family; his grandfather Cornelius Foley was a maintenance foreman for the Great Northern railroad in

Foley graduated from the Jesuit-run Gonzaga Preparatory School

Gonzaga Preparatory School in Spokane, Washington, is a private, Catholic high school in the Inland Northwest. As a Jesuit institution, "G-Prep" has been recognized for its college preparation education and community service.

History

Gonzaga Hi ...

in Spokane in 1946 and attended Gonzaga University

Gonzaga University (GU) () is a private Jesuit university in Spokane, Washington. It is accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. Founded in 1887 by Joseph Cataldo, an Italian-born priest and Jesuit missionary, the ...

for three years; he completed his bachelor's degree at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seattl ...

in Seattle, then attended its School of Law

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, l ...

and was awarded a law degree in 1957.

Following law school, Foley entered private practice. In 1958, he began working in the Spokane County

Spokane County is a county located in the U.S. state of Washington. As of the 2020 census, its population was 539,339, making it the fourth-most populous county in Washington. The largest city and county seat is Spokane, the second largest cit ...

prosecutor's office as a deputy prosecuting attorney

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal trial ...

, and later taught at Gonzaga's School of Law

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, l ...

(in Spokane) from 1958 to 1959. He joined the state attorney general

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney gener ...

's office in 1961 as an assistant attorney general.

In 1961, Foley moved to Washington, D.C., and joined the staff of Senator Henry Jackson. He left Jackson's office in 1964 to run for

Congressional service

In 1964, Foley was unopposed for the Democratic nomination for Washington's 5th congressional seat, which included Spokane. He faced 11-termRepublican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

incumbent Walt Horan in the general election and won by seven points, one of many swept into office in the 1964 Democratic landslide. He was re-elected without significant difficulty until 1978, when in a 3-person race, he won only 48% of the vote. Two years later, he narrowly defeated Republican candidate John Sonneland (52% to 48%). Though the fifth district became increasingly conservative, Foley didn't face serious opposition again until his defeat in 1994

File:1994 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 1994 Winter Olympics are held in Lillehammer, Norway; The Kaiser Permanente building after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; A model of the MS Estonia, which sank in the Baltic Sea; Nelson ...

. Foley voted in favor of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (officially Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., and sometimes referred to as MLK Day) is a federal holiday in the United States marking the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. It is observed on the third Mond ...

as a federal holiday

Federal holidays in the United States are the eleven calendar dates that are designated by the U.S. government as holidays. On U.S. federal holidays, non-essential federal government offices are closed and federal government employees are paid ...

, and the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987

The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, or Grove City Bill, is a United States legislative act that specifies that entities receiving federal funds must comply with civil rights legislation in all of their operations, not just in the program ...

(as well as to override President Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

's veto).

During his first term in the House, Foley was appointed to the Agriculture Committee and the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee. He served on the latter committee through 1975, when he became chairman of the Agriculture Committee. In 1981, when Foley was appointed Majority Whip

A whip is an official of a political party whose task is to ensure party discipline in a legislature. This means ensuring that members of the party vote according to the party platform, rather than according to their own individual ideology ...

, he left the Agriculture Committee to serve on the House Administration Committee. Six years later, January 1987, he was elected House Majority Leader.

Speaker of the House

In June 1989, Jim Wright ofTexas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

resigned as Speaker of the House of Representatives (only the fourth speaker ever to resign) and from Congress amid a House Ethics Committee

The Committee on Ethics, often known simply as the Ethics Committee, is one of the committees of the United States House of Representatives. Prior to the 112th Congress it was known as the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct.

The House Et ...

investigation into his personal business dealings. In the June 6 election to succeed Wright, Foley was the victor, receiving 251 votes; his Republican opponent, Minority Leader Robert H. Michel

Robert Henry Michel (; March 2, 1923 – February 17, 2017) was an American Republican Party politician who was a member of the United States House of Representatives for 38 years. He represented central Illinois' 18th congressional distric ...

, received 164 votes.

During the 101st Congress, Foley presided over the House as it passed a landmark update to the 1963 Clean Air Act, measures protecting persons with disabilities, the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a piece of American legislation that ensures students with a disability are provided with a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) that is tailored to their individual needs. IDEA wa ...

, as well as the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 The Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 (BEA) (, title XIII; ; codified as amended at scattered sections of 2 U.S.C. & ) was enacted by the United States Congress as title XIII of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, to enforce the deficit re ...

. The budget act, a part of the massive Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90; ) is a United States statute enacted pursuant to the budget reconciliation process to reduce the United States federal budget deficit. The Act included the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 whic ...

, established the "pay-as-you-go

Pay as you go or PAYG may refer to:

Finance

* Pay-as-you-go tax, or pay-as-you-earn tax

* Pay-as-you-go pension plan

* PAYGO, the practice in the US of financing expenditures with current funds rather than borrowing

* PAUG, a structured financia ...

" process for discretionary spending and taxes, and was signed into law by President George H. W. Bush on November 5, 1990, contrary to his 1988

File:1988 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The oil platform Piper Alpha explodes and collapses in the North Sea, killing 165 workers; The USS Vincennes (CG-49) mistakenly shoots down Iran Air Flight 655; Australia celebrates its Bicenten ...

campaign promise not to raise taxes. This became a significant issue during the 1992 presidential campaign.

In 1993, the 103rd Congress

The 103rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 19 ...

passed a second omnibus budget act through which the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

was able to raise additional revenue and balance the federal budget. Signed into law by President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

signed on August 10, 1993, the measure stirred controversy because of the tax increases it imposed. Under Foley's leadership Congress also passed the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) is a United States labor law requiring covered employers to provide employees with job-protected, unpaid leave for qualified medical and family reasons. The FMLA was a major part of President Bill C ...

, the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act, as well as the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act ( Pub.L. 103–159, 107 Stat. 1536, enacted November 30, 1993), often referred to as the Brady Act or the Brady Bill, is an Act of the United States Congress that mandated federal background checks on ...

plus legislation that laid the groundwork for the "Don't ask, don't tell

"Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT) was the official United States policy on military service of non-heterosexual people, instituted during the Clinton administration. The policy was issued under Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 on Decemb ...

" military service policy in 1993 which was then instituted by the Clinton Administration in 1994.

Term limits

During his time in the House, Foley repeatedly opposed efforts to imposeterm limit

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

s on Washington state's elected officials, winning the support of the state's voters to reject term limits in a 1991 referendum; however, in 1992, a term limit ballot initiative was approved by the state's voters.

Foley brought suit, challenging the constitutionality of a state law setting eligibility requirements on federal offices. Foley won his suit, with a United States District Court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district co ...

declaring that states did not have the authority under the United States Constitution to limit the terms of federal officeholders.

However, in Foley's bid for a 16th term in the House, his Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

opponent, George Nethercutt

George Rector Nethercutt Jr. (born October 7, 1944) is an American lawyer, author, and politician. Nethercutt is the founder and chairman of The George Nethercutt Foundation. He was a Republican member of the United States House of Representative ...

, used the issue against him, citing the caption of the federal case brought by Foley, "Foley against the People of the State of Washington". Nethercutt vowed that if elected, he would not serve more than three terms in the House (but ultimately served for five terms). Foley lost in a narrow race. While Foley had usually relied on large margins in Spokane to carry him to victory, in 1994 he won Spokane by only 9,000 votes, while Nethercutt did well enough in the rest of the district to win overall by just under 4,000 votes. Since Foley left office, no Democrat has garnered more than 45 percent of the district's vote.

Foley became the first incumbent Speaker of the House to lose his bid for re-election since Galusha A. Grow in 1862. He is sometimes viewed as a political casualty of the term limits controversy of the early 1990s. President Bill Clinton attributed Foley's defeat to his support for the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994.

Later career

From 1995 to 1998, Foley was head of theFederal City Council

Federal City Council is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that promotes economic development in the city of Washington, D.C., in the United States. Incorporated on September 13, 1954, it is one of the most powerful private groups in the city, ...

, a group of business, civic, education, and other leaders interested in economic development in Washington, D.C.

In 1997, Foley was appointed as the 25th U.S. Ambassador to Japan

The is the ambassador from the United States of America to Japan.

History

Since the opening of Japan by Commodore Matthew C. Perry, in 1854, the U.S. has maintained diplomatic relations with Japan, except for the ten-year period between t ...

by President Bill Clinton, and was part of the US government response to the deaths of Japanese schoolchildren caused by a US submarine.

He served as ambassador until 2001.

Foley was a Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

delegate to the 2004 and 2012 Democratic National Conventions. On July 9, 2003, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Gary Locke awarded the Washington Medal of Merit

The Washington Medal of Merit is one of three statutory civilian decorations issued by the state of Washington, the others being the Washington Medal of Valor and the Washington Gift of Life Award (formerly the Washington Gift of Life Medal). Wa ...

, the state's highest honor, to Foley. He was North American Chairman of the Trilateral Commission

The Trilateral Commission is a nongovernmental international organization aimed at fostering closer cooperation between Japan, Western Europe and North America. It was founded in July 1973 principally by American banker and philanthropist David ...

.Trilateral Commission

The Trilateral Commission is a nongovernmental international organization aimed at fostering closer cooperation between Japan, Western Europe and North America. It was founded in July 1973 principally by American banker and philanthropist David ...

Foley, bio notes

/ref>

Death

Foley died at his home in Washington, D.C. on October 18, 2013, following months of hospice care after suffering a series of strokes and a bout withpneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

. He was 84 and is survived by his wife, Heather. He had been experiencing aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection that is due to a relatively large amount of material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs. Signs and symptoms often include fever and cough of relatively rapid onset. Complications may inc ...

. Services were held at St. Aloysius Church at Gonzaga University

Gonzaga University (GU) () is a private Jesuit university in Spokane, Washington. It is accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. Founded in 1887 by Joseph Cataldo, an Italian-born priest and Jesuit missionary, the ...

, as well as in Washington, D.C. Speaker John Boehner, and Nancy Pelosi, who had also served as Speaker, issued statements honoring Foley. In a White House statement, President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

called Foley a "legend of the United States Congress" who "represented the people of Washington's 5th district with skill, dedication, and a deep commitment to improving the lives of those he was elected to serve.", going on to praise Foley for his bipartisanship and subsequent ambassadorial service under former President Clinton. Vice President Joe Biden also released an official statement, saying "Tom was a good friend and a dedicated public servant.", citing his work in Congress with Foley in the 1980s on budgetary issues. Washington Governor Jay Inslee

Jay Robert Inslee (; born February 9, 1951) is an American politician, lawyer, and economist who has served as the 23rd governor of Washington since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a member of the U.S. House of Represent ...

also released a statement, acknowledging Foley's efforts to reach consensus and emphasize mutual common ground, and his work in the legal system and in Congress. Former President George H. W. Bush stated that Foley "represented the very best in public service--and our political system" and "never got personal or burned bridges."

Honors

* Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (UK). * Order of Merit (Germany). *Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

(France).

* Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, Grand Cordon (Japan), 1995.

* Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University, Pullman. Established in 1995.

* Thomas S. Foley Memorial Highway (U.S. Route 395

U.S. Route 395 (US 395) is a U.S. Route in the western United States. The southern terminus of the route is in the Mojave Desert at Interstate 15 near Hesperia. The northern terminus is at the Canada–US border near Laurier, where the road ...

), dedicated in 2018.

Electoral history

Congressional elections

* November 3, 1964: * November 8, 1966: * November 5, 1968: * November 3, 1970: * November 7, 1972: * November 5, 1974: * November 2, 1976: * November 7, 1978: * November 4, 1980: * November 2, 1982: * November 6, 1984: * November 4, 1986: * November 8, 1988: * November 6, 1990: * November 3, 1992: * November 8, 1994:Speaker elections

* June 6, 1989: : * January 3, 1991: : * January 5, 1993: :References

External links

* * * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Foley, Tom 1929 births 2013 deaths 20th-century American diplomats 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians 21st-century American diplomats Ambassadors of the United States to Japan American people of Irish descent American prosecutors Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Deaths from pneumonia in Washington, D.C. Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Washington (state) Gonzaga Preparatory School alumni Gonzaga University alumni Gonzaga University faculty Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Lawyers from Spokane, Washington Majority leaders of the United States House of Representatives Politicians from Spokane, Washington Recipients of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers Speakers of the United States House of Representatives State attorneys University of Washington School of Law alumni Washington (state) lawyers