Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, ( Kenninghall,

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, ( Kenninghall,

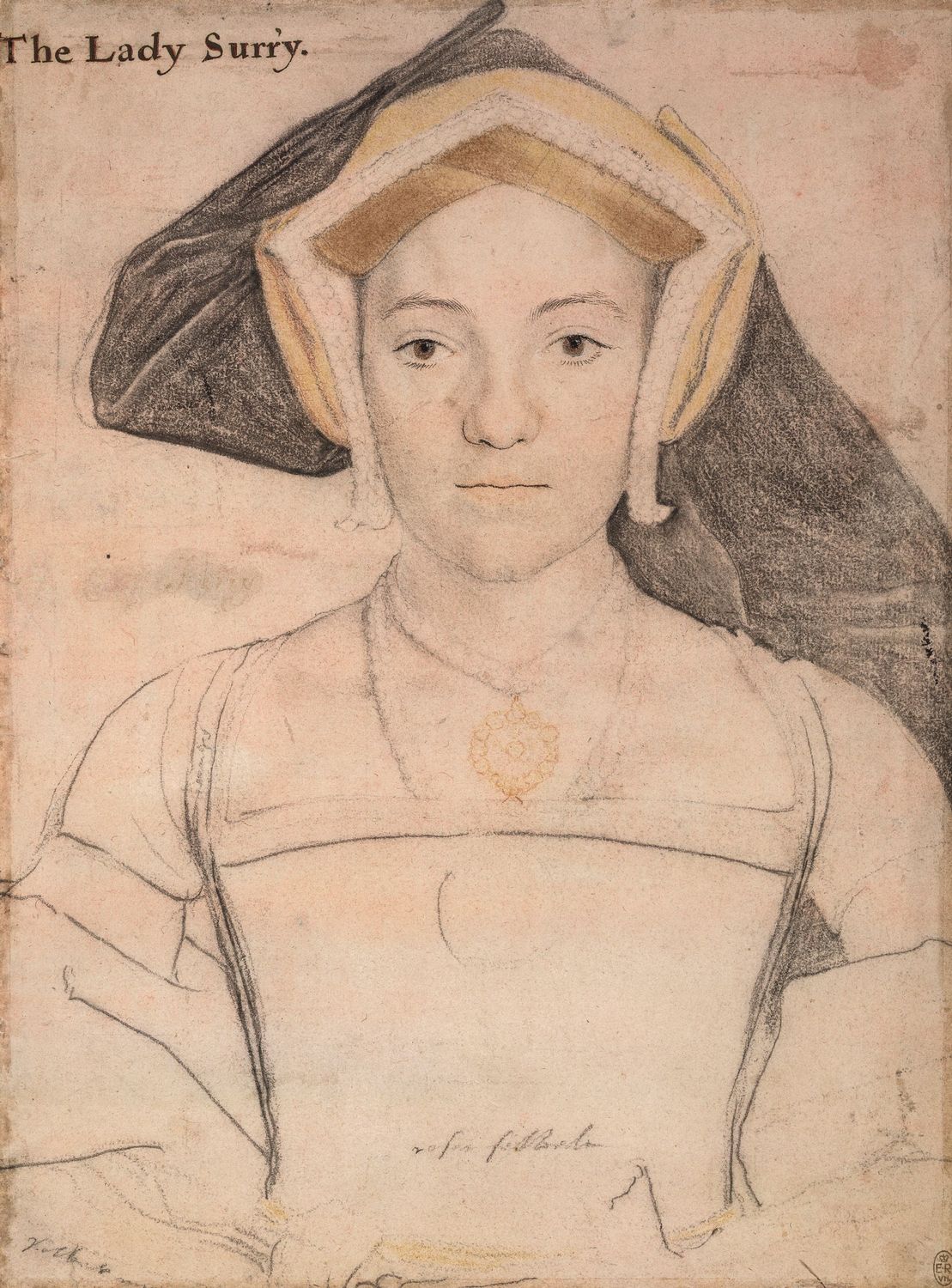

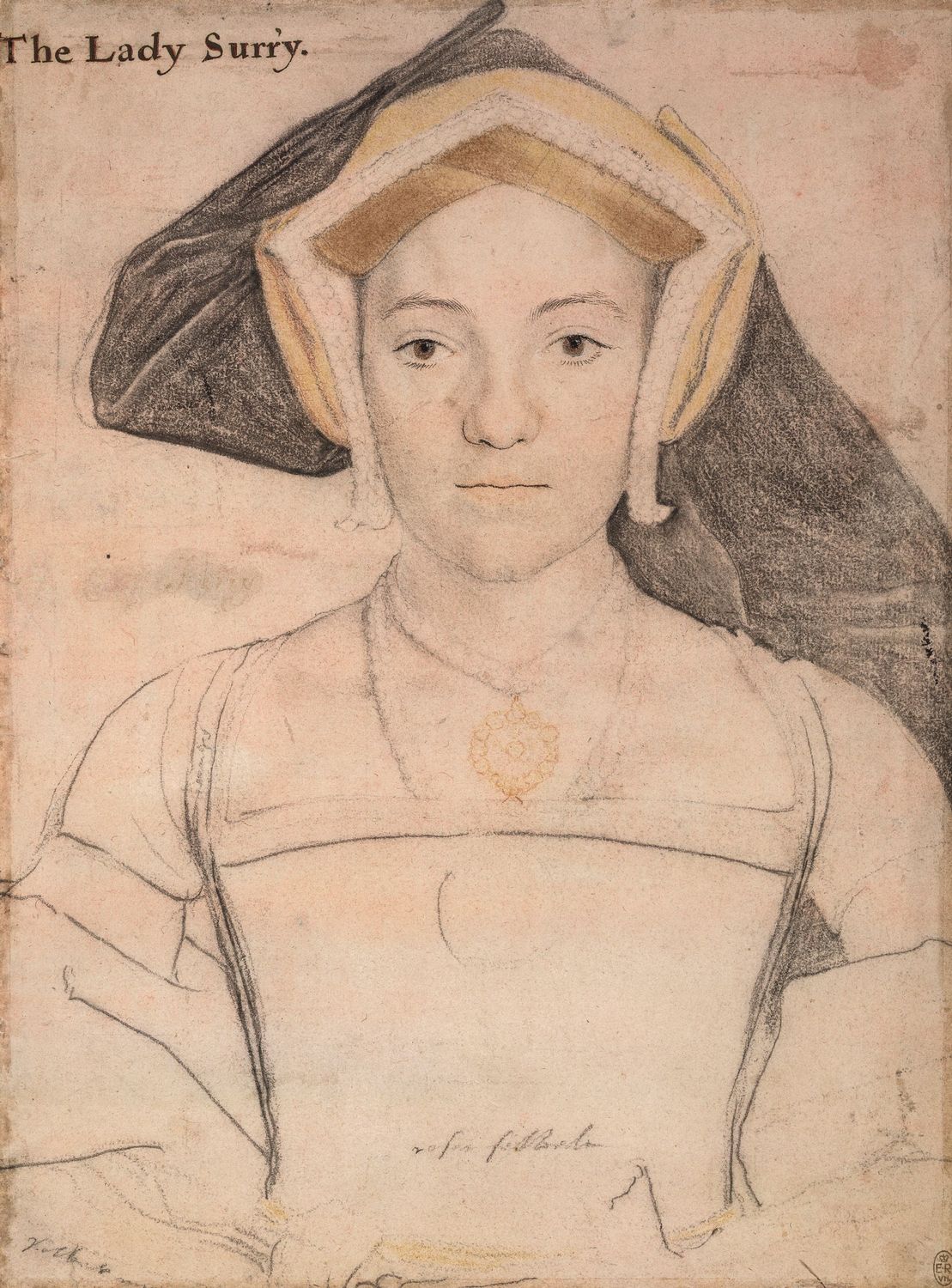

Norfolk was born at his family's house at Kenninghall, Norfolk on March 10, 1536, being the eldest son of the Earl of Surrey and his wife Frances de Vere. His younger siblings were

Norfolk was born at his family's house at Kenninghall, Norfolk on March 10, 1536, being the eldest son of the Earl of Surrey and his wife Frances de Vere. His younger siblings were

Thomas Howard's first wife was Mary FitzAlan, daughter of

Thomas Howard's first wife was Mary FitzAlan, daughter of

Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, 10 March 1536Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, 2 June 1572) was an English nobleman and politician. Although from a family with strong Roman Catholic leanings, he was raised a Protestant. He was a second cousin of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

through her maternal grandmother, and held many high offices during her reign.

Norfolk was the son of the poet, soldier and politician Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. He is believed to have commissioned Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

, probably in 1567, to compose his renowned motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Ma ...

in forty voice-parts, '' Spem in alium''.

He was executed for his role in the Ridolfi plot.

Early life, family, and religion

Norfolk was born at his family's house at Kenninghall, Norfolk on March 10, 1536, being the eldest son of the Earl of Surrey and his wife Frances de Vere. His younger siblings were

Norfolk was born at his family's house at Kenninghall, Norfolk on March 10, 1536, being the eldest son of the Earl of Surrey and his wife Frances de Vere. His younger siblings were Jane

Jane may refer to:

* Jane (given name), a feminine given name

* Jane (surname), related to the given name

Film and television

* Jane (1915 film), ''Jane'' (1915 film), a silent comedy film directed by Frank Lloyd

* Jane (2016 film), ''Jane'' (20 ...

, Henry, Katherine, and Margaret. After Surrey's execution in January 1547, their aunt, Mary Howard, Duchess of Richmond, assigned the upbringing and guardianship of the children to John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the s ...

, the Protestant martyrologist

A martyrology is a catalogue or list of martyrs and other saints and beati arranged in the calendar order of their anniversaries or feasts. Local martyrologies record exclusively the custom of a particular Church. Local lists were enriched by ...

, who remained a lifelong recipient of Norfolk's patronage. Although Norfolk was educated and raised Protestant, a vein of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was never far below the surface, not least because the Howards had always remained loyal to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in the turbulent years of the Anglican Reformation (his father had fallen out of favour in part because he was a Catholic, and his grandfather, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk, had been a prisoner in the Tower

A tower is a tall structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting structures.

Towers are specific ...

from the end of the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and was kept there throughout the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

for the same reason, although he was then released early in the rule of Queen Mary, who was also a Catholic). As soon as he was released from the Tower in 1553, his grandfather removed John Foxe's tutorship and reassigned the further education of his seventeen-year-old heir to the devout Catholic John White, the bishop of Lincoln (1554-56). In July 1554 he became first gentleman of the chamber to Mary's consort, King Philip II, and in November he was with them at the opening of parliament. His father predeceased his grandfather, so Norfolk was able to first inherit the earldom of Surrey

Earl of Surrey is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created five times. It was first created for William de Warenne, a close companion of William the Conqueror. It is currently held as a subsidiary title by the Dukes of Norfolk. ...

(the title held by his father at the time of his death) in 1553 after Mary reinstated the Howard titles, and after his grandfather's death in 1554, the dukedom of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The du ...

. As he was a minor, however, his extensive estates including fifty-six manors were held by the crown until he came of age.

He was a second cousin of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

through her maternal grandmother, Lady Elizabeth Howard, and he was trusted with public office despite his family's history and leanings towards the Church of Rome.

For Norfolk to have been a Catholic, disguised as a Protestant so as not to attract the attention of the authorities, was not unusual during the turbulent years of the Reformation. Many English Catholics took the attitude of publicly showing themselves as Protestants, but secretly and privately professing and maintaining their Catholic faith. After the death of his first wife Mary FitzAlan in 1557 and to marry Margaret Audley who would be his second wife, had to request a dispensation from Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

since Elizabeth was Margaret's cousin.

Career

While still young, Norfolk was Earl Marshal of England and Queen's Lieutenant in the North. From February to July 1560, he was commander of the English army in Scotland in support of theLords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves "the Faithful", were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scot ...

opposing Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. Sh ...

. He negotiated the February 1560 Treaty of Berwick by which the Congregation invited English assistance, and after the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives ...

was signed in July of that year he was able to return to Court.

Norfolk was the Principal of the commission at York in 1568 to hear evidence against Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

, presented by Regent Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland. A supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent of Scotland for hi ...

, including the casket letters.

He is believed to have commissioned Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

in 1567 to compose his famous motet in forty-parts, Spem in alium.

Legal troubles and execution

Having lost his third wife in 1567, and despite having presided at the York commission, Norfolk planned what would have been his fourth marriage, toMary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

. The Scottish statesman William Maitland of Lethington

William Maitland of Lethington (15259 June 1573) was a Scottish politician and reformer, and the eldest son of poet Richard Maitland.

Life

He was educated at the University of St Andrews.

William was the renowned "Secretary Lethington" to ...

favoured the proposed union, and Mary herself consented to it, but Norfolk was unwilling to take up arms. He was briefly involved in the Northern Rebellion

The Rising of the North of 1569, also called the Revolt of the Northern Earls or Northern Rebellion, was an unsuccessful attempt by Catholic nobles from Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of ...

, which was organised in part by his brother-in-law Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland

Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland (18 August 154216 November 1601) was an English nobleman and one of the leaders of the Rising of the North in 1569.

He was the son of Henry Neville, 5th Earl of Westmorland and Lady Anne Manners, second ...

, in an attempt to free Mary, and Elizabeth ordered his arrest for this in October 1569. He was imprisoned for nine months and was released in August 1570 because as there was insufficient evidence to accuse him of treason, since he was not directly involved in organising the Northern Rebellion. Following his release and after some hesitation, he agreed to participate in the Ridolfi plot with King Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

to put Mary on the English throne and restore Catholicism in England. Elizabeth's intelligence network (particularly William Cecil, Lord Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from ...

) soon became aware of the plot, which also involved Spanish Intelligence, whose purpose was to overthrow her and possibly even assassinate her. Norfolk initially denied involvement, but subsequently admitted to a role in the plot.

The evidence against Norfolk was now far more compelling than it had been in 1569-70. It was clear that it remained his intention to marry Mary, despite Elizabeth’s objections. It was also apparent that he had engaged in a conspiracy to overthrow, and perhaps kill, Elizabeth. At his trial on 16 January 1572, which lasted twelve hours, Norfolk pleaded his innocence. However, a jury of twenty-six of his fellow nobles, including Burghley and Leicester, unanimously found him guilty of treason, whereupon he was sentenced to death.

Norfolk having been condemned to death by a jury of his peers, it was reasonable to suppose that his execution would quickly follow. Indeed, it was rumoured that he was to be executed on the last day of January, whereupon crowds flocked to the Tower. In fact, Elizabeth, torn between the demands of justice on the one hand and Norfolk’s ‘nearness of blood nd… his superiority of honour’ on the other, could not be brought to sign the death warrant until 9 February, and on the 10th she countermanded her instructions. She did the same thing a fortnight later, to the dismay of Burghley and the Privy Council. They insisted that Parliament be assembled to debate the urgent threat posed by Norfolk and Mary, although parliaments normally met only once every three or four years and the previous parliament had been dissolved just ten months earlier.

This new parliament, the fourth of Elizabeth’s reign, assembled on 8 May 1572. Over the course of the next three weeks, Burghley and the Council used their spokesmen in the Commons to press the case for executing Norfolk. In late May, two members went so far as to observe that by failing to execute the duke, the queen was demonstrating that she believed the guilty verdict to be incorrect, which ‘dishonoureth the nobles that have condemned him’. Initially Elizabeth refused to relent. Indeed, as late as 21 May Leicester remarked that he could ‘see no likelihood’ that Norfolk would be executed. However, the queen’s mind was changed when she faced strong parliamentary pressure to execute Mary. As Stephen Alford has observed, Norfolk’s execution ‘was the political price Elizabeth had to pay to save the Scottish Queen’. Even so, Elizabeth was determined that the decision to execute the duke should be seen to be hers rather than Parliament’s. On Saturday 31 May the crown’s spokesmen in the Commons persuaded the lower House, with great difficulty, to postpone petitioning the queen to execute the duke until the following Monday (2 June), ‘in hope to hear news before that time’. That hint was well taken, as Norfolk finally went to the block less than one hour before the Commons reassembled.

Shortly before seven in the morning on 2 June 1572, Norfolk, was led the short distance to a specially erected scaffold on Tower Hill, accompanied by his former tutor Foxe and by Alexander Nowell

Alexander Nowell (13 February 1602, aka Alexander Noel) was an Anglican priest and theologian. He served as Dean of St Paul's during much of Elizabeth I's reign, and is now remembered for his catechisms.

Early life

He was the eldest son of Jo ...

, Dean of St Paul’s. After mounting the steps he addressed the crowd which had assembled to witness his execution. Despite admitting that he deserved to die, he declared himself to be partly innocent, whereupon he was interrupted by an official, who warned him that he should not try to clear himself, having been ‘tried as honourably as any nobleman hath ever been in this land’. Urged to wind up quickly, as ‘the hour is passed’, Norfolk ended his speech by denying that he was a Catholic, as was commonly believed. After bidding a tearful farewell to Foxe and Nowell, and forgiving the public hangman, the duke removed his doublet and laid his head on the block. Before a silent crowd, which had been urged not to shout out to avoid ‘frighting’ his soul, Norfolk’s head was severed with a single stroke.

Norfolk was the first nobleman to be executed during Elizabeth's reign, being the first member of the nobility to face the block since Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk

Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, 3rd Marquess of Dorset (17 January 151723 February 1554), was an English courtier and nobleman of the Tudor period. He was the father of Lady Jane Grey, known as "the Nine Days' Queen".

Origins

He was born on ...

– the father of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

– was executed early in Mary I’s reign. Equally striking is that he was the premier nobleman of England, the queen’s second cousin and a leading member of the Privy Council. Until recently, he had also been much admired by Elizabeth and Burghley. Indeed, in 1565 Burghley had described Norfolk as ‘wise, just, modest, careful’ and, despite his youth – he was then aged just 27 – ‘a father and stay to this country’. In the immediate aftermath of his execution, Elizabeth was reportedly ‘somewhat sad’ at the duke’s death.

Norfolk's lands and titles were forfeit, although much of the estate was later restored to his sons. The title of Duke of Norfolk was restored, four generations later, to his great-great-grandson Thomas Howard.

Marriages and issue

First wife

Thomas Howard's first wife was Mary FitzAlan, daughter of

Thomas Howard's first wife was Mary FitzAlan, daughter of Henry FitzAlan, 19th Earl of Arundel

Henry Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel KG (23 April 151224 February 1580) was an English nobleman, who over his long life assumed a prominent place at the court of all the later Tudor sovereigns, probably the only person to do so.

Court caree ...

and his first wife Katherine Grey. She died after a year of marriage, having given birth to a son, who, on the death of his grandfather, inherited the Arundel title and estates:

* Philip Howard (28 June 155719 October 1595), who became the 20th Earl of Arundel. Shortly after his death, he was declared a martyr and he was finally canonised by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

in 1970, being one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. His tomb and sanctuary is in Arundel Cathedral.

It is from this marriage that modern dukes of Norfolk derive their surname of 'FitzAlan-Howard' and their seat in Arundel. Although her funeral effigy is at Framlingham church, Mary FitzAlan was not buried there but first at the church of St. Clement Danes

St Clement Danes is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Although the first church on the site was reputedly founded in the 9th century by the Danes, the current ...

, Temple Bar and then, as directed in her grandson's will, her remains were transferred to the Fitzalan Chapel in Arundel.

Second wife

Norfolk next married another heiress, Margaret Audley, widow of Sir Henry Dudley and daughter ofThomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden

Thomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden KG, PC, KS (30 April 1544), was an English barrister and judge who served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1533 to 1544.

Early life

Audley was born in Earls Colne, Essex, the son of Geoffrey ...

and his second wife Elizabeth Grey. Thus Margaret was the first cousin of Howard's first wife. For the marriage to conform with Catholic canon law

The canon law of the Catholic Church ("canon law" comes from Latin ') is "how the Church organizes and governs herself". It is the system of laws and ecclesiastical legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Cath ...

, a dispensation had to be requested from Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

, given the close relationship of Norfolk's first wife to Margaret Audley. Norfolk sent his lawyers to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

to negotiate the dispensation, but the delays in obtaining (in addition to the fact that by this time Queen Mary had died in November 1558 and Elizabeth ascended the throne, who began to reverse the restoration of Catholicism in England) it meant that the marriage was approved and later ratified by the House of Lords in March 1559.

Norfolk's children by his marriage to Margaret were:

* Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk;

* Lord William Howard

Lord William Howard (19 December 1563 – 7 October 1640) was an English nobleman and antiquary, sometimes known as "Belted or Bauld (bold) Will".

Early life

Howard was born on 19 December 1563 at Audley End in Essex. He was the third son ...

, ancestor of the Earls of Carlisle

Earl of Carlisle is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England.

History

The first creation came in 1322, when Andrew Harclay, 1st Baron Harclay, was made Earl of Carlisle. He had already been summoned to Parliame ...

;

* Lady Elizabeth Howard (died in childhood);

* Lady Margaret Howard

Margaret Audley Howard's tomb effigy is found at St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham.

Third wife

After Margaret's death in 1563, Norfolk married Elizabeth Leyburne (15364 September 1567), widow of Thomas Dacre, 4th Baron Dacre ofGillesland

Gilsland is a village in northern England about west of Hexham, and about east of Carlisle, Cumbria, Carlisle, which straddles the border between Cumbria and Northumberland. The village provides an amenity centre for visitors touring Hadrian ...

and daughter of Sir James Leyburn

Sir James Leyburn (c. 1490 – 20 August 1548), also Laybourne, Labourn, etc., was a senior representative of one of the powerful families within the Barony of Kendal. He was at different times a Justice of the Peace for Westmorland, Escheat ...

.

Norfolk's three sons by his first two wives, Philip, Thomas, and William, married, respectively, Anne, Margaret, and Elizabeth Dacre. The Dacre sisters were the daughters of Elizabeth Leyburne by her marriage to Thomas Dacre and were, thereby, stepsisters to Norfolk's sons.

Attempted fourth marriage

Norfolk became a widower again after his third wife's death in 1567. In 1568,Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

fled to England and was imprisoned by Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

. Thomas Howard was suggested as a husband for Mary, as he was a cousin to Queen Elizabeth and the wealthiest landowner in the country. Together they would have a strong claim on England's throne as Mary was also Elizabeth's cousin, through the royal Tudor line. This suited Norfolk, as he was ambitious and felt that Elizabeth consistently undervalued him.

Therefore, Norfolk supported the Rising of the North in 1569 in an attempt to free Mary and later marry her. It is still debated whether this rebellion actually aimed to overthrow Elizabeth and whether Mary even knew about it beforehand. Howard soon lost his nerve and the plan failed, but he made another effort to marry Mary in 1571 as part of the Ridolfi Plot. This was a plan to murder Elizabeth and free Mary. She would then marry Howard so that they could take the throne together. Elizabeth's government discovered the plot, and Howard's servants betrayed him under torture. Norfolk was imprisoned by Elizabeth and put on trial in January 1572. He was found guilty, and beheaded on Tower Hill, London, in June.Hodder Education History for Edexcel: Early Elizabethan England

Depictions

*Thomas Howard appears as a character in thePhilippa Gregory

Philippa Gregory (born 9 January 1954) is an English historical novelist who has been publishing since 1987. The best known of her works is '' The Other Boleyn Girl'' (2001), which in 2002 won the Romantic Novel of the Year Award from the Rom ...

novels ''The Virgin's Lover'' and ''The Other Queen'', and in the novel ''I, Elizabeth'' by Rosalind Miles.

*A highly fictionalized version of the 4th Duke of Norfolk appears as a villain, played by Christopher Eccleston

Christopher Eccleston (; born 16 February 1964) is an English actor. A two-time BAFTA Award nominee, he is best known for his television and film work, which includes his role as the ninth incarnation of the Doctor in the BBC sci-fi series '' ...

, in the 1998 film '' Elizabeth''.

*Another version of the Duke is in the BBC mini-series '' The Virgin Queen'', played by Kevin McKidd.

*In the Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a fourth television service ...

documentary ''Elizabeth'' (2000) presented by David Starkey, the Duke is portrayed by actor John Gully.

See also

*John George Howard

John George Howard (born John Corby; July 27, 1803 – February 3, 1890) was the official surveyor and civil engineer for the government of Toronto in Upper Canada and later Canada. He was also the first professional architect in Toronto. He d ...

, a Toronto architect who claims to be related to the Duke.

References

Further reading

* * papers from Norfolk's treason trial 1568–1572. * * * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Norfolk, Thomas Howard, 4th Duke Of 1536 births 1572 deaths304

Year 304 ( CCCIV) was a leap year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. It was known in the Roman Empire as the Year of the Consulship of Diocletian and Maximian (or, less frequently, year 1057 ''Ab ...

303

__NOTOC__

Year 303 ( CCCIII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. It was known in the Roman Empire as the Year of the Consulship of Diocletian and Maximian (or, less frequently, ye ...

Earls Marshal

Barons Mowbray

*16

Thomas Howard, 04th Duke of Norfolk

Knights of the Garter

Lord-Lieutenants of Buckinghamshire

Lord-Lieutenants of Norfolk

People executed under the Tudors for treason against England

Howard, Thomas

16th-century English politicians

People convicted under a bill of attainder

Executions at the Tower of London

Prisoners in the Tower of London

Executed English people

People executed by Tudor England by decapitation

People executed under Elizabeth I

Burials at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula

English politicians convicted of crimes

Court of Mary I of England