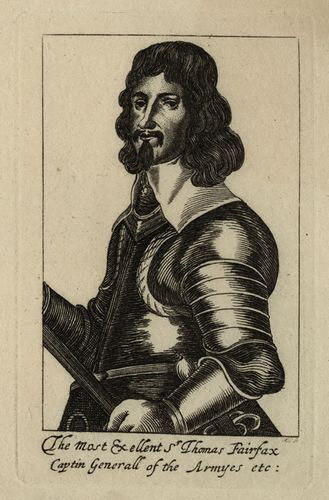

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Baron Fairfax of Cameron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and

The Fairfaxes, father and son, though serving at first under King

The Fairfaxes, father and son, though serving at first under King

Fairfax was more at home in the field than at the head of a political committee, and, finding events too strong for him and that his officers were rallying around the more radical and politically shrewd Cromwell, he sought to resign his commission as commander-in-chief. He was, however, persuaded to retain it. He thus remained the titular chief of the army party, and with the greater part of its objects he was in complete, sometimes most active, sympathy. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second Civil War, Fairfax succeeded his father in the barony and in the office of governor of

Fairfax was more at home in the field than at the head of a political committee, and, finding events too strong for him and that his officers were rallying around the more radical and politically shrewd Cromwell, he sought to resign his commission as commander-in-chief. He was, however, persuaded to retain it. He thus remained the titular chief of the army party, and with the greater part of its objects he was in complete, sometimes most active, sympathy. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second Civil War, Fairfax succeeded his father in the barony and in the office of governor of

During the

During the

Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

commander-in-chief during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

. An adept and talented commander, Fairfax led Parliament to many victories, notably the crucial Battle of Naseby

The Battle of Naseby took place on 14 June 1645 during the First English Civil War, near the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Parliamentarian New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, destroyed the main ...

, becoming effectively military ruler of England, but was eventually overshadowed by his subordinate Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, who was more politically adept and radical in action against Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. Fairfax became unhappy with Cromwell's policy and publicly refused to take part in Charles's show trial. Eventually he resigned, leaving Cromwell to control the country. Because of this, and also his honourable battlefield conduct and his active role in the Restoration of the monarchy after Cromwell's death, he was exempted from the retribution exacted on many other leaders of the revolution.

Early life

Thomas Fairfax was born at Denton Hall, halfway betweenIlkley

Ilkley is a spa town and civil parish in the City of Bradford in West Yorkshire, in Northern England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Ilkley civil parish includes the adjacent village of Ben Rhydding and is a ward within the ...

and Otley

Otley is a market town and civil parish at a bridging point on the River Wharfe, in the City of Leeds metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. Historically a part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, the population was 13,668 at the 20 ...

in the West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

, on 17 January 1612, the eldest son of Ferdinando Fairfax, 2nd Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Ferdinando Fairfax, 2nd Lord Fairfax of Cameron MP (29 March 1584 – 14 March 1648) was an English nobleman and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1614 and 1648. He was a commander in the Parliamentary army in ...

(his family title of Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Lord Fairfax of Cameron is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. Despite holding a Scottish peerage, the Lords Fairfax of Cameron are members of an ancient Yorkshire family, of which the Fairfax baron ...

was in the peerage of Scotland

The Peerage of Scotland ( gd, Moraireachd na h-Alba, sco, Peerage o Scotland) is one of the five divisions of peerages in the United Kingdom and for those peers created by the King of Scots before 1707. Following that year's Treaty of Unio ...

, then still independent from England, which was why he was able to sit in the English House of Commons after he inherited it). His dark hair and eyes and a swarthy complexion earned him the nickname "Black Tom".

Fairfax studied at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. The ...

, and Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and W ...

(1626–1628), then volunteered to join Sir Horace Vere's expedition to fight for the Protestant cause in the Netherlands. In 1639 he commanded a troop of Yorkshire dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s which marched with King Charles I against the Scots in the First Bishops' War

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

, which ended with the Pacification of Berwick

The Treaty of Berwick (also known as the Peace of Berwick or the Pacification of Berwick) was signed on 19 June 1639 between England and Scotland. It ended minor hostilities the day before. Archibald Johnston was involved in the negotiations be ...

before any fighting took place. In the Second Bishops' War

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

the following year, the English army was routed at the Battle of Newburn

The Battle of Newburn, also known as The Battle of Newburn Ford, took place on 28 August 1640, during the Second Bishops' War. It was fought at Newburn, just outside Newcastle, where a ford crossed the River Tyne. A Scottish Covenanter army o ...

. Fairfax fled with the rest of the defeated army but was nevertheless knighted in January 1641 for his services.

Pre-Civil War events

The Fairfaxes, father and son, though serving at first under King

The Fairfaxes, father and son, though serving at first under King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, were opposed to the arbitrary prerogative of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

, and Sir Thomas declared that "his judgment was for the Parliament as the king and kingdom's great and safest council". When Charles endeavoured to raise a guard for his own person at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, intending it, as the event afterwards proved, to form the nucleus of an army, Fairfax was employed to present a petition to his sovereign, entreating him to hearken to the voice of his parliament, and to discontinue the raising of troops. This was at a great meeting

A meeting is when two or more people come together to discuss one or more topics, often in a formal or business setting, but meetings also occur in a variety of other environments. Meetings can be used as form of group decision making.

Defini ...

of the freeholders and farmers of Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

convened by the king on Heworth Moor

Heworth is part of the city of York in North Yorkshire, England, about north-east of the centre. No longer in general referred to as a village, "Heworth Village" is now the name of a specific road. The name "Heworth" is Anglo-Saxon and means ...

near York. Charles attempted to ignore the petition, pressing his horse forward, but Fairfax followed him and placed the petition on the pommel of the king's saddle.

Civil War

When the civil war broke out in 1642, his father, Lord Fairfax, was appointed general of the Parliamentary forces in the north, and Sir Thomas was made lieutenant-general of the horse under him. Both father and son distinguished themselves in the campaigns in Yorkshire. In 1643 a minor battle between Royalists forCharles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and a small group of Roundheads

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

under Fairfax, who were en route from Tadcaster

Tadcaster is a market town and civil parish in the Selby district of North Yorkshire, England, east of the Great North Road, north-east of Leeds, and south-west of York. Its historical importance from Roman times onward was largely as the ...

to Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

, took place at Seacroft

Seacroft is an outer-city suburb/township consisting mainly of council estate housing covering an extensive area of east Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It lies in the LS14 Leeds postcode area, around east of Leeds city centre.

It sits in th ...

. Fairfax was obliged to retreat across Bramham moor and summed up the Battle of Seacroft Moor as 'the greatest loss we ever received'.

Sometimes severely defeated, but more often successful, and always energetic, prudent and resourceful, father and son contrived to keep up the struggle until the crisis of 1644, when York was held by the Marquess of Newcastle against the combined forces of the English Parliamentarians and the Scots, and Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist caval ...

hastened with all available forces to its relief. A gathering of eager national forces within a few square miles of ground naturally led to a battle, and Marston Moor

The Battle of Marston Moor was fought on 2 July 1644, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of 1639 – 1653. The combined forces of the English Parliamentarians under Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester and the Scottish Covenanters und ...

(2 July 1644) proved decisive for the struggle in the north. The younger Fairfax bore himself with the greatest gallantry in the battle and, though severely wounded, managed to join Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

and the victorious cavalry on the other wing. One of his brothers, Colonel Charles Fairfax, was killed in the action. But the Marquess of Newcastle fled the kingdom, and the Royalists abandoned all hope of retrieving their affairs. The city of York was taken, and nearly the whole of the north submitted to the Parliament.

In the West, South and South West of England, however, the Royalist cause was still strong. The war had lasted two years, and the nation began to complain of the contributions that were exacted of and the excesses that were committed by the military. Dissatisfaction was expressed with the military commanders and, as a preliminary step to reform, the Self-denying Ordinance

The Self-denying Ordinance was passed by the English Parliament on 3 April 1645. All members of the House of Commons or Lords who were also officers in the Parliamentary army or navy were required to resign one or the other, within 40 days fr ...

was passed. This involved the removal of the Earl of Essex from the supreme command, along with other Members of Parliament. This was followed by the New Model Ordinance, which replaced the locally raised Parliamentary regiments with a unified army. Sir Thomas Fairfax was selected as the new Lord General, with Cromwell as his Lieutenant-General and cavalry commander. After a short preliminary campaign, the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

justified its existence, and "the rebels' new brutish general", as the king called him, proved his capacity as commander-in-chief in the decisive Battle of Naseby

The Battle of Naseby took place on 14 June 1645 during the First English Civil War, near the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Parliamentarian New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, destroyed the main ...

(14 June 1645). The king fled to Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

. Fairfax besieged Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, and was successful at Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

, Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a large historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. Its population currently stands at around 41,276 as of 2022. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies alon ...

and Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

. The whole of the west was soon reduced.

Fairfax arrived in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

on 12 November 1645. In his progress towards the capital he was accompanied by applauding crowds. Complimentary speeches and thanks were presented to him by both houses of parliament, along with a jewel of great value set with diamonds, and a sum of money. The king had returned from Wales and established himself at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, where there was a strong garrison but, ever vacillating, he withdrew secretly, and proceeded to Newark to throw himself into the arms of the Scots Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

army there. Oxford capitulated in June 1646 following the final siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

, and by the end of September 1646 Charles had neither army nor garrison in England, following the surrender of Thomas Blagge

Colonel Thomas Blagge (13 July 1613 – 4 November 1660) served as Groom of the Chamber to Charles I and his son Charles II. He fought for the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and following the Execution of Charles I in January ...

at Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

after a siege conducted by Fairfax. In January 1647 the King was delivered up by the Covenanters to the commissioners of England's parliament. Fairfax met the king beyond Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

, and accompanied him during the journey to Holdenby, treating him with the utmost consideration in every way. "The general", said Charles, "is a man of honour

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

, and keeps his word which he had pledged to me."

With the collapse of the Royalist cause came a confused period of negotiations between the Parliament and the King, between the King and the Scots, and between the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

s and the Independents in and out of Parliament. In these negotiations the New Model Army soon began to take a most active part. The Lord General was placed in the unpleasant position of intermediary between his own officers and Parliament. In July the person of the King was seized by Cornet Joyce

Cornet George Joyce (born 1618) was a low-ranking officer in the Parliamentary New Model Army during the English Civil War.

Between 2 and 5 June 1647, while the New Model Army was assembling for rendezvous at the behest of the recently formed ...

, a subaltern of cavalry—an act which sufficiently demonstrated the hopelessness of controlling the army by its Articles of War

The Articles of War are a set of regulations drawn up to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first known usage of the phrase is in Robert Monro's 1637 work ''His expedition with the worthy Scot's regiment called Mac- ...

.

Fairfax was more at home in the field than at the head of a political committee, and, finding events too strong for him and that his officers were rallying around the more radical and politically shrewd Cromwell, he sought to resign his commission as commander-in-chief. He was, however, persuaded to retain it. He thus remained the titular chief of the army party, and with the greater part of its objects he was in complete, sometimes most active, sympathy. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second Civil War, Fairfax succeeded his father in the barony and in the office of governor of

Fairfax was more at home in the field than at the head of a political committee, and, finding events too strong for him and that his officers were rallying around the more radical and politically shrewd Cromwell, he sought to resign his commission as commander-in-chief. He was, however, persuaded to retain it. He thus remained the titular chief of the army party, and with the greater part of its objects he was in complete, sometimes most active, sympathy. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second Civil War, Fairfax succeeded his father in the barony and in the office of governor of Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

. In the field against the English Royalists in 1648 he displayed his former energy and skill, and his operations culminated in the successful siege of Colchester

The siege of Colchester occurred in the summer of 1648 when the English Civil War reignited in several areas of Britain. Colchester found itself in the thick of the unrest when a Royalist army on its way through East Anglia to raise sup ...

, after the surrender of which place he approved the execution of the Royalist leaders Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle

Sir George Lisle (baptised 10 July 1615 – 28 August 1648) was a professional soldier from London who briefly served in the later stages of the Eighty and Thirty Years War, then fought for the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cap ...

, holding that these officers had broken their parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

. At the same time Cromwell's great victory of Preston

Preston is a place name, surname and given name that may refer to:

Places

England

*Preston, Lancashire, an urban settlement

**The City of Preston, Lancashire, a borough and non-metropolitan district which contains the settlement

**County Boro ...

crushed the faction of the Scots Covenanters who had made an engagement with the king, the Engagers

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamentarians after his defeat in the First Civil War.

Bac ...

.

John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

, in a sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

written during the siege of Colchester, called upon the Lord General to settle the kingdom, but the crisis was now at hand. Fairfax was in agreement with Cromwell and the army leaders in demanding the punishment of Charles, and he was still the effective head of the army. He approved, if he did not take an active part in, Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

(6 December 1648), but on the last and gravest of the questions at issue he set himself in deliberate and open opposition to the policy of the officers. He was placed at the head of the judges who were to try the King, and attended the preliminary sitting of the court, but absented himself after this. The most likely explanation is that when he saw that they were serious about intending to execute the king he declined to have anything to do with this.Wedgewood, C.V. ''The Trial of Charles I''

In calling over the court, when the crier pronounced the name of Fairfax, it is said that his wife, Anne Fairfax

Anne, Lady Fairfax (born Anne Vere, also known as Anne Fairfax; 1617/1618 – 1665) was an English noblewoman. She was the wife of Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron, commander-in-chief of the New Model Army. She followed her husband as ...

, shouted from the gallery that "he had more wit than to be there". Later when the court said that they were acting for "all the good people of England", she shouted "No, nor the hundredth part of them!". This resulted in an investigation and Anne was asked or required to leave the court. It was said that Anne could not forbear, as Bulstrode Whitelocke

Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke (6 August 1605 – 28 July 1675) was an English lawyer, writer, parliamentarian and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England.

Early life

He was the eldest son of Sir James Whitelocke and Elizabeth Bulstrode, and was ...

says, to exclaim aloud against the proceedings of the High Court of Justice. In February 1649 Fairfax was elected Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Cirencester

Cirencester (, ; see below for more variations) is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of ...

in the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

. Anne was later approached to intercede on the King's behalf to prevent his execution.

Fairfax's last service as Commander-in-chief was the suppression of the Leveller

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populis ...

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among memb ...

at Burford

Burford () is a town on the River Windrush, in the Cotswold hills, in the West Oxfordshire district of Oxfordshire, England. It is often referred to as the 'gateway' to the Cotswolds. Burford is located west of Oxford and southeast of Che ...

in May 1649. He had given his adhesion to the new order of things, and had been reappointed Lord General, but he merely administered the affairs of the army; when in 1650 Scots Covenanter Kirk Party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parlia ...

eventually declared for Charles II, and the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

resolved to send an army to Scotland in order to prevent an invasion of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Fairfax resigned his commission. Cromwell desired to see him continue as Commander-in-chief, as did those planning the war, but Fairfax could not support the war. Cromwell was appointed his successor, "Captain-general and Commander-in-chief of all the forces raised or to be raised at authority of Parliament within the Commonwealth of England."

Interregnum

During the

During the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execu ...

in 1654, Fairfax was elected MP for the newly created constituency of West Riding

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

in the First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the Ho ...

. He received a pension of £5,000 a year, and lived in retirement at his Yorkshire home of Nunappleton

Nun Appleton Priory was a priory near Appleton Roebuck, North Yorkshire, England. It was founded as a nunnery c. 1150, by Eustace de Merch and his wife. It was dissolved by 1539, when the nuns were receiving pensions.

Nun Appleton Hall

Subsequen ...

until after the death of the Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

in 1658. Nunappleton and Fairfax's retirement there are the subject of Andrew Marvell's country house poem, ''Upon Appleton House

"Upon Appleton House" is a poem written by Andrew Marvell for Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron. It was written in 1651, when Marvell was working as a tutor for Fairfax's daughter, Mary. An example of a country house poem, "Upon Appleto ...

''. The troubles of the later Commonwealth recalled Lord Fairfax to political activity, and in 1659 he was elected MP for Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

in the Third Protectorate Parliament

The Third Protectorate Parliament sat for one session, from 27 January 1659 until 22 April 1659, with Chaloner Chute and Thomas Bampfylde as the Speakers of the House of Commons. It was a bicameral Parliament, with an Upper House having a pow ...

.

Restoration

For the last time Fairfax's appearance in arms helped to shape the future of the country, whenGeorge Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

invited him to assist in the operations about to be undertaken against John Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

* John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

* John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c ...

's army. In December 1659 he appeared at the head of a body of Yorkshire gentlemen, and such was the influence of Fairfax's name and reputation that 1,200 horse quit Lambert's colours and joined him. This was speedily followed by the breaking up of all Lambert's forces, and that day secured the restoration of the monarchy. For these actions, along with his honourable conduct in the civil war, he was spared from the wave of Royalist retributions. In April 1660 Fairfax was re-elected MP for Yorkshire in the Convention Parliament. He was put at the head of the commission appointed by the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

to wait upon Charles II at the Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

and urge his speedy return. His actions assisted the Stuart Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

. Fairfax provided the horse which Charles rode at his coronation.

Later life

The remaining eleven years of the life of Lord Fairfax were spent in retirement at his seat in Yorkshire. His wife died in 1665 and Fairfax died at Nun Appleton Priory in 1671. He was buried atBilbrough

Bilbrough () is a village and civil parish in the Selby District of North Yorkshire, England, south-west of York, and just outside the York city boundary. According to the 2001 Census it had a population of 319 increasing to 348 at the 2011 ...

, near York.

Bibliography

Fairfax had a taste forliterature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

. He translated some of the Psalm

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived f ...

s, and wrote poems on solitude, the Christian warfare, the shortness of life, etc. During the last year or two of his life he wrote two Memorials which have been published—one on the northern actions in which he was engaged in 1642–44, and the other on some events in his tenure of the chief command. At York and at Oxford he endeavoured to save the libraries from pillage, and he enriched the Bodleian

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the sec ...

with some valuable manuscripts. His correspondence was edited by G.W. Johnson and published in 1848–49 in four volumes.

The metaphysical poet Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell (; 31 March 1621 – 16 August 1678) was an English metaphysical poet, satirist and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1659 and 1678. During the Commonwealth period he was a colleague and friend ...

wrote "Upon Appleton House, To My Lord Fairfax", nominally about Fairfax's home, but also his character as well as England during his era.

Family

Fairfax married Hon. Anne de Vere, daughter ofHorace Vere, 1st Baron Vere of Tilbury

Horace Vere, 1st Baron Vere of Tilbury (1565 – 2 May 1635) (also ''Horatio Vere'' or ''Horatio de Vere'') was an English military leader during the Eighty Years' War and the Thirty Years' War, a brother of Francis Vere. He was sent to the Pa ...

and Mary Tracy, on 20 June 1637. They had a daughter, Hon. Mary Fairfax (30 July 163820 October 1704), who married George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros, (30 January 1628 – 16 April 1687) was an English statesman and poet.

Life

Early life

George was the son of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, favourite of James I a ...

.

Fairfax was succeeded as Lord Fairfax by a cousin, Henry Fairfax, 4th Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Henry Fairfax, 4th Lord Fairfax of Cameron (30 December 1631 – 13 April 1688) of Denton, Yorkshire was a Scottish peer and politician. He was the grandson of Thomas Fairfax, 1st Lord Fairfax of Cameron.

He was born the son of Henry Fair ...

.

Analysis

As a soldier he was exact and methodical in planning, in the heat of battle "so highly transported that scarce any one durst speak a word to him", chivalrous and punctilious in his dealings with his own men and the enemy. Honour and conscientiousness were equally the characteristics of his private and public character. But his modesty and distrust of his powers made him less effectual as astatesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political career at the national or international level.

Statesman or Statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

* ''The Statesman'' (Oregon), a ...

than as a soldier, and above all he is placed at a disadvantage by being both in war and peace overshadowed by his associate Cromwell, who was politically talented and able to manipulate public antipathy against Charles to lead to his execution, something Fairfax never wanted.

In fiction

Fairfax, played by actorDougray Scott

Stephen Dougray Scott (born 25 November 1965) is a Scottish actor. He has appeared in the films ''Ever After'' (1998), '' Mission: Impossible 2'' (2000), ''Enigma'' (2001), ''Hitman'' (2007), and ''My Week with Marilyn'' (2011).

Early life

Sc ...

, is a pivotal character in the 2003 film '' To Kill a King'', as well as in Rosemary Sutcliff

Rosemary Sutcliff (14 December 1920 – 23 July 1992) was an English novelist best known for children's books, especially historical fiction and retellings of myths and legends. Although she was primarily a children's author, some of her novel ...

's 1953 historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other t ...

'' Simon'', being portrayed as inspiring and fair. He also appears as a central character in Sutcliff's 1959 novel ''The Rider of the White Horse'', which gives an account of the early stage of the Civil War from the point of view of his wife, and in Howard Brenton

Howard John Brenton FRSL (born 13 December 1942) is an English playwright and screenwriter. While little-known in the United States, he is celebrated in his home country and often ranked alongside contemporaries such as Edward Bond, Caryl Chu ...

's 2012 play '' 55 Days''. Douglas Wilmer portrayed him in the 1970 Ken Hughes

Ken or KEN may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Ken'' (album), a 2017 album by Canadian indie rock band Destroyer.

* ''Ken'' (film), 1964 Japanese film.

* ''Ken'' (magazine), a large-format political magazine.

* Ken Masters, a main character in ...

film ''Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

''. He was played by Jerome Willis

Jerome Barry Willis (23 October 1928 – 11 January 2014) was a prominent British stage and screen actor with more than 100 screen credits to his name.

Willis had a leading role in the ITV drama series ''The Sandbaggers'' as Matthew Peele. He ...

in the 1975 historical film '' Winstanley''. He appears in Michael Arnold's novel ''Marston Moor'', which includes an account of Fairfax's adventures in the eponymous battle. He was also a central character, played by Nigel Anthony, in the 1988 BBC Radio production of Don Taylor's play ''God's Revolution''.

Notes

Citations

References

* cites * * * * * * . Attribution: * * , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fairfax, Thomas 1612 births 1671 deaths 17th-century English nobility Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Burials in North Yorkshire English military personnel of the Eighty Years' War English MPs 1648–1653 English MPs 1654–1655 English MPs 1659 English MPs 1660Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

New Model Army generals

Roundheads

Lords of Parliament (pre-1707)

Lords Fairfax of Cameron

Monarchs of the Isle of Man

Parliamentarian military personnel of the English Civil War

People from the Borough of Harrogate

Military personnel from Yorkshire