Thomas A. Hendricks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

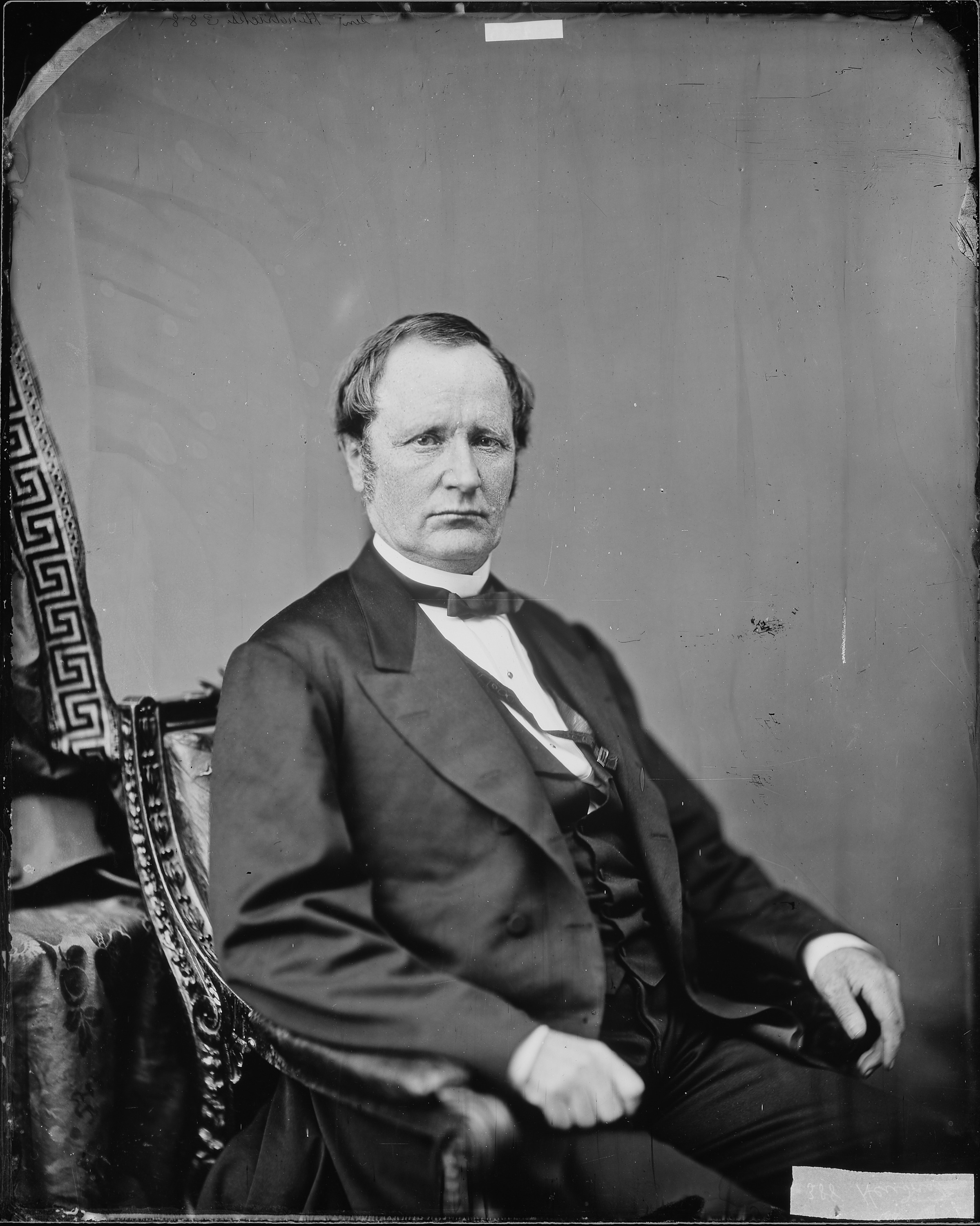

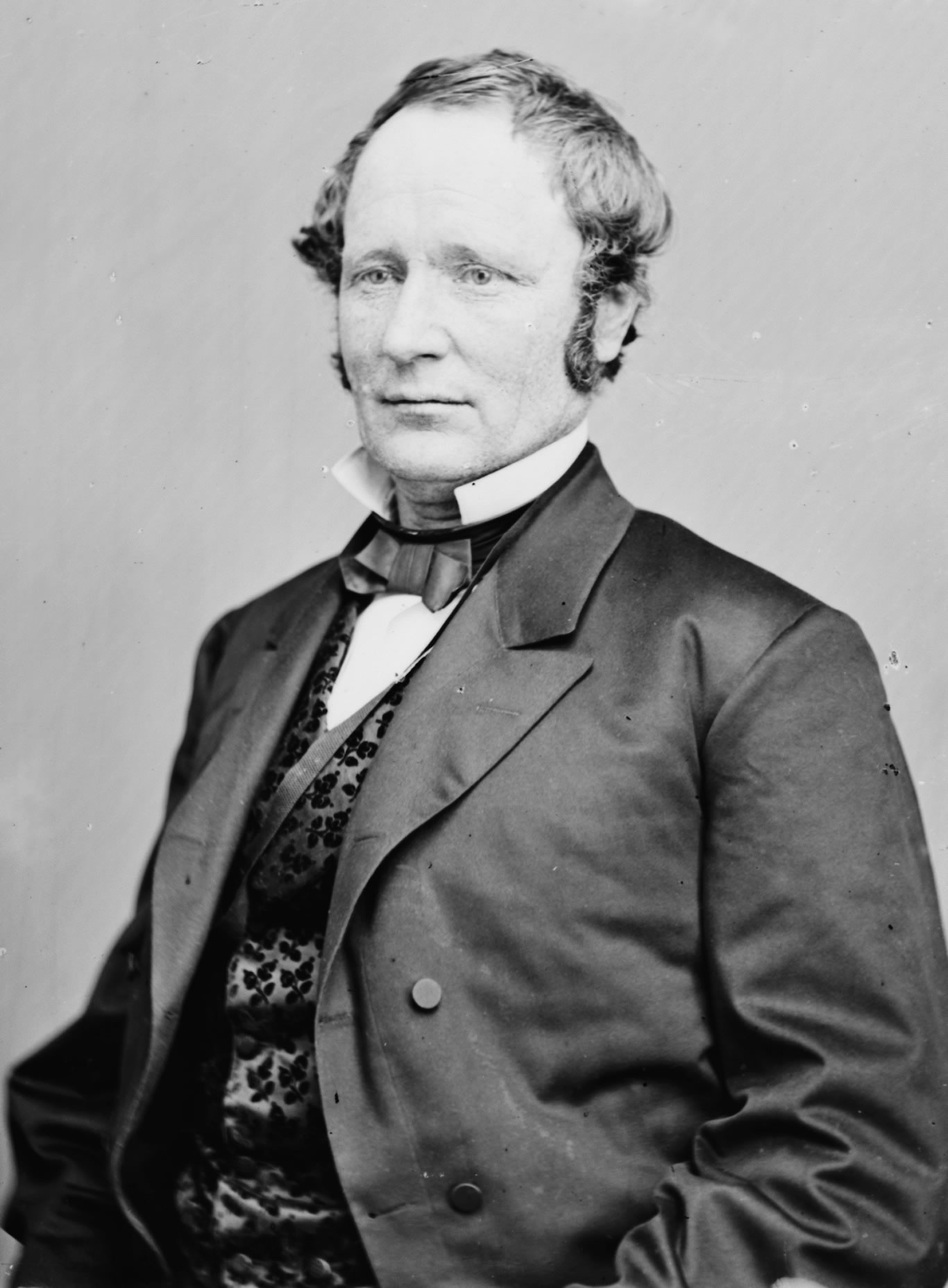

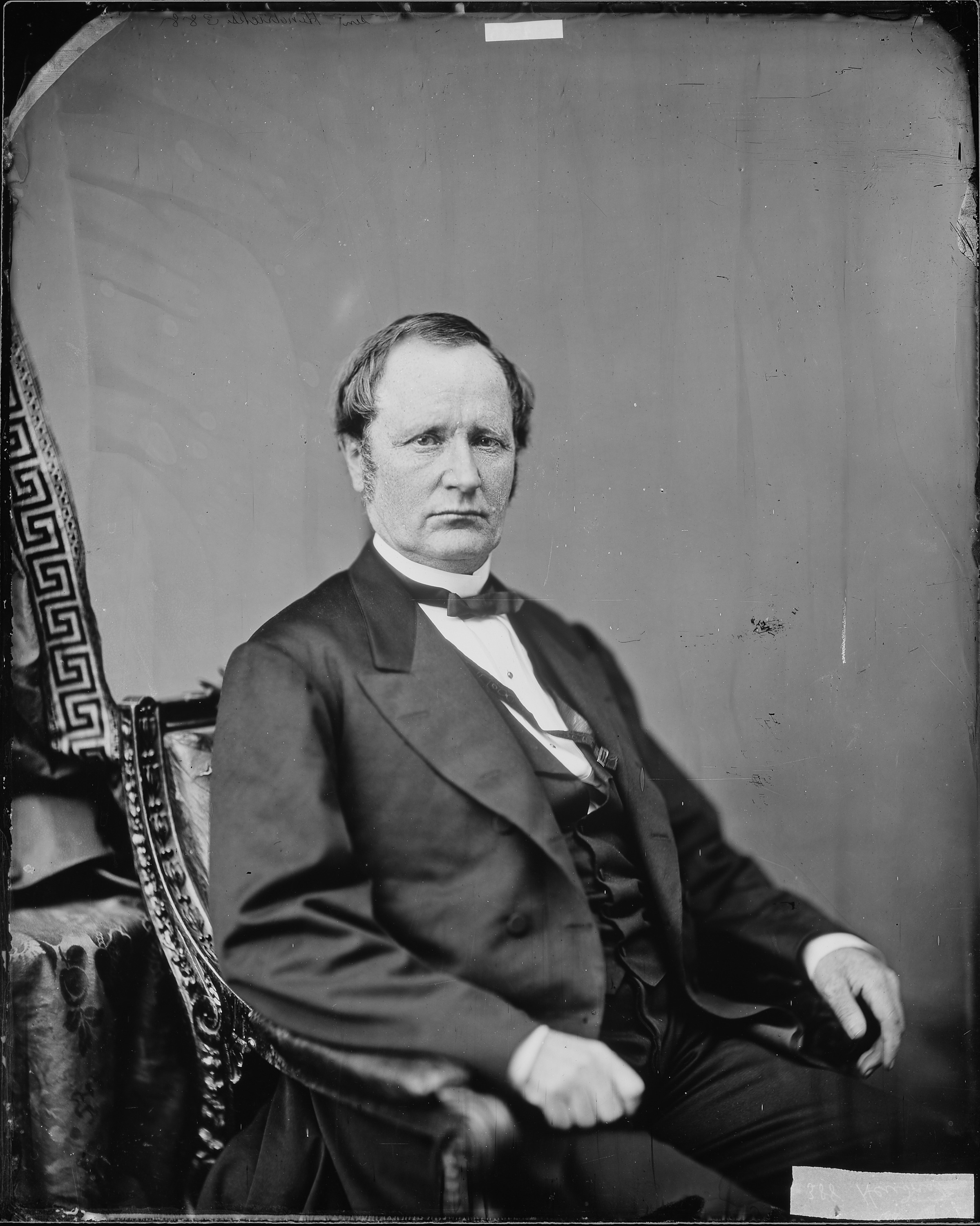

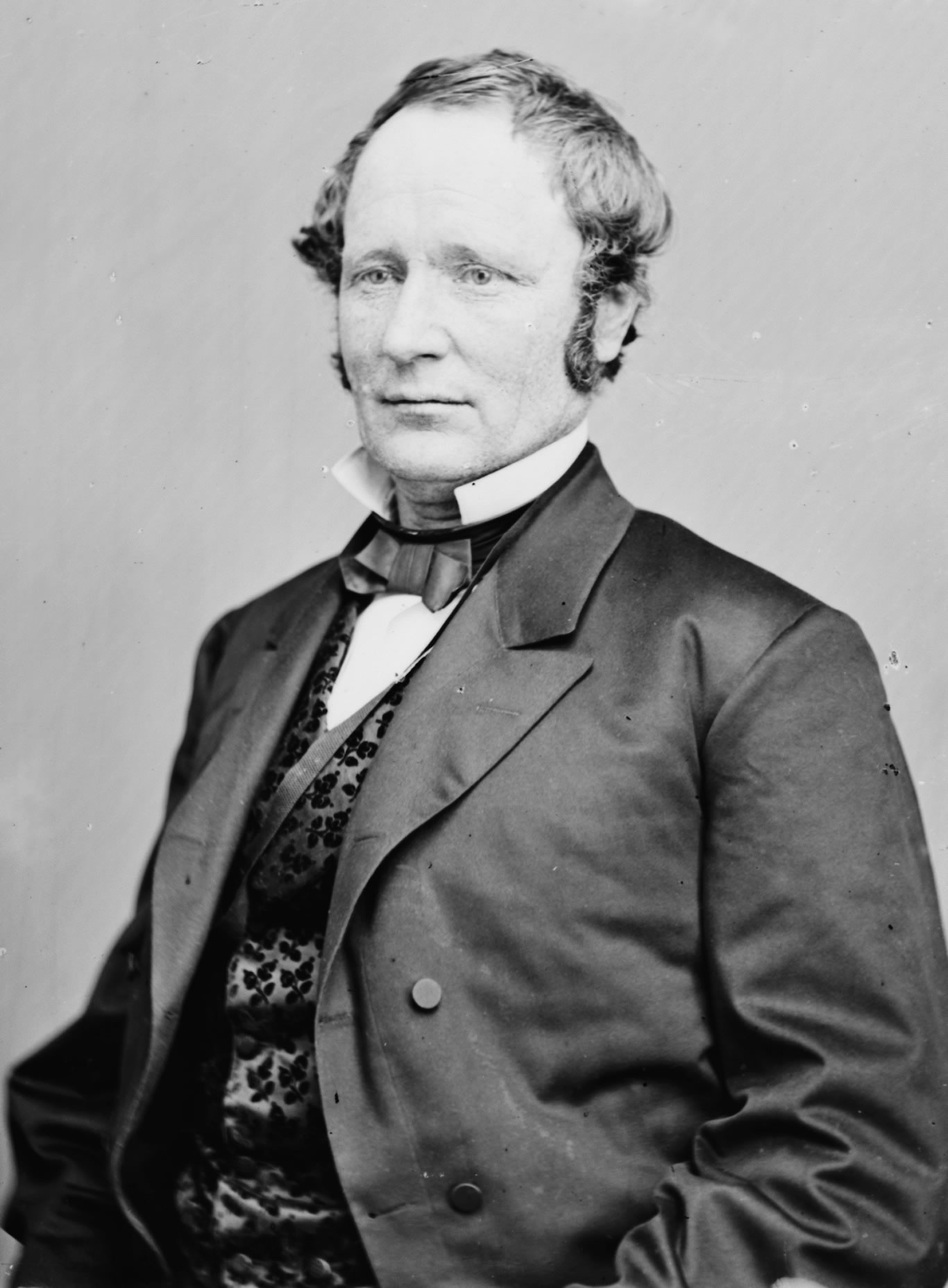

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from

Hendricks also opposed the attempt to remove President

Hendricks also opposed the attempt to remove President

Hendricks ran for

Hendricks ran for

Hendricks died unexpectedly on November 25, 1885, during a trip home to Indianapolis. He complained of feeling ill the morning of November 24, went to bed early, and died in his sleep the following day, aged 66. His reported last words were "Free at last!".

Hendricks's funeral service at Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral in Indianapolis was a large one. Hundreds of dignitaries were in attendance, including President Grover Cleveland, and thousands of people gathered along the city's street to see the 1.2 mile long funeral cortege as it traveled from downtown Indianapolis to

Hendricks died unexpectedly on November 25, 1885, during a trip home to Indianapolis. He complained of feeling ill the morning of November 24, went to bed early, and died in his sleep the following day, aged 66. His reported last words were "Free at last!".

Hendricks's funeral service at Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral in Indianapolis was a large one. Hundreds of dignitaries were in attendance, including President Grover Cleveland, and thousands of people gathered along the city's street to see the 1.2 mile long funeral cortege as it traveled from downtown Indianapolis to

* Hendricks remains the only vice president who did not serve as president whose portrait appears on U.S. paper currency. An engraved portrait of Hendricks appears on a $10 "tombstone"

* Hendricks remains the only vice president who did not serve as president whose portrait appears on U.S. paper currency. An engraved portrait of Hendricks appears on a $10 "tombstone"

copy

* * * * * * * *

"Thomas A. Hendricks: “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was”

Indiana Historical Bureau

Indiana Historical Bureau

Hendricks biography

Biographical Dictionary of Congress

Hendricks obituaries

Indiana Historic Newspaper Digitization Project] * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hendricks, Thomas A. 1819 births 1885 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century vice presidents of the United States Candidates in the 1868 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1872 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1876 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election 1876 United States vice-presidential candidates 1884 United States vice-presidential candidates Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Hanover College alumni Democratic Party governors of Indiana Indiana lawyers People from Shelbyville, Indiana People from Muskingum County, Ohio Democratic Party members of the Indiana House of Representatives Vice presidents of the United States Democratic Party vice presidents of the United States Democratic Party United States senators from Indiana General Land Office Commissioners Cleveland administration cabinet members Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Indiana Politicians from Indianapolis Members of the Odd Fellows

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

who served as the 16th governor of Indiana

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state governmen ...

from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice p ...

from March until his death in November 1885. Hendricks represented Indiana in the U.S. House of Representatives (1851–1855) and the U.S. Senate (1863–1869). He also represented Shelby County, Indiana

Shelby County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 44,436. The county seat (and only incorporated city) is Shelbyville.

History

After the American Revolutionary War established US sov ...

, in the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. Th ...

(1848–1850) and as a delegate to the 1851 Indiana constitutional convention. In addition, Hendricks served as commissioner of the General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an independent agency of the United States government responsible for public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 to take over functions previously conducted by the United States Department o ...

(1855–1859). Hendricks, a popular member of the Democratic Party, was a fiscal conservative. He defended the Democratic position in the U.S. Senate during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

and voted against the Thirteenth

In music or music theory, a thirteenth is the note thirteen scale degrees from the root of a chord and also the interval between the root and the thirteenth. The interval can be also described as a compound sixth, spanning an octa ...

, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth

In music, a fifteenth or double octave, abbreviated ''15ma'', is the interval between one musical note and another with one-quarter the wavelength or quadruple the frequency. It has also been referred to as the bisdiapason. The fourth harmonic, ...

Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. He also opposed Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

's removal from office following Johnson's impeachment in the U.S. House.

Born in Muskingum County, Ohio

Muskingum County is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 86,410. Its county seat is Zanesville. Nearly bisected by the Muskingum River, the county name is based on a Delaware American India ...

, Hendricks moved to Indiana, with his parents in 1820; the family settled in Shelby County in 1822. After graduating from Hanover College

Hanover College is a private college in Hanover, Indiana, affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA). Founded in 1827 by Reverend John Finley Crowe, it is Indiana's oldest private college. The Hanover athletic teams participate in the H ...

, class of 1841, Hendricks studied law in Shelbyville, Indiana

Shelbyville is a city in Addison Township, Shelby County, in the U.S. state of Indiana and is the county seat. The population was 20,067 as of the 2020 census.

History

In 1818, the land that would become Shelbyville was ceded to the U ...

, and Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and north of Maryland and the ...

. He was admitted to the Indiana bar in 1843. Hendricks began his law practice in Shelbyville, moved to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

in 1860, and established a private law practice with Oscar B. Hord

Oscar B. Hord (August 31, 1829 – January 15, 1888) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the sixth Indiana Attorney General from November 3, 1862 to November 3, 1864.

Biography

Hord was born in 1829 in Maysville, Kentucky. He wa ...

in 1862. The firm evolved into Baker & Daniels

Baker & Daniels LLP is a predecessor to the firm Faegre Baker Daniels LLP (now Faegre Drinker), which resulted after the firm merged in 2012 with Minneapolis-based Faegre & Benson. Baker & Daniels counseled clients in transactional, regulato ...

, one of the state's leading law firms. Hendricks also ran for election as Indiana's governor three times, but won only once. In 1872, on his third and final attempt, Hendricks defeated General Thomas M. Brown by a margin of 1,148 votes. His term as governor of Indiana was marked by numerous challenges, including a strong Republican majority in the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. Th ...

, the economic Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, and an economic depression. One of Hendricks's lasting legacies during his tenure as governor was initiating discussions to fund construction of the present-day Indiana Statehouse

The Indiana Statehouse is the state capitol building of the U.S. state of Indiana. It houses the Indiana General Assembly, the office of the Governor of Indiana, the Indiana Supreme Court, and other state officials. The Statehouse is located in ...

, which was completed after he left office. A memorial to Hendricks was installed on the southeast corner of its grounds in 1890.

Hendricks, a lifelong Democrat, was his party's candidate for U.S. vice president with New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Samuel Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden (February 9, 1814 – August 4, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 25th Governor of New York and was the Democratic candidate for president in the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. Tilden was ...

as its presidential nominee in the controversial presidential election of 1876

The following elections occurred in the year 1876.

Europe

* 1876 Dalmatian parliamentary election

* 1876 French legislative election

* 1876 Leominster by-election

* 1876 Spanish general election

North America Canada

* 1876 Prince Edward Isl ...

. Although they won the popular vote, Tilden and Hendricks lost the election by one vote in the Electoral College to the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

's presidential nominee, Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

, and his vice presidential running mate, William A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler (June 30, 1819June 4, 1887) was an American politician and attorney. He served as a United States representative from New York from 1861 to 1863 and 1869 to 1877, and the 19th vice president of the United States from 1877 t ...

. Despite his poor health, Hendricks accepted his party's nomination for vice president in the election of 1884 as Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's running mate. Cleveland and Hendricks won the election, but Hendricks only served as vice president for about eight months, from March 4, 1885, until his death on November 25, 1885, in Indianapolis. He is buried in Indianapolis's Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high point ...

.

Early life and education

Hendricks was born on September 7, 1819, inMuskingum County, Ohio

Muskingum County is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 86,410. Its county seat is Zanesville. Nearly bisected by the Muskingum River, the county name is based on a Delaware American India ...

, near East Fultonham and Zanesville

Zanesville is a city in and the county seat of Muskingum County, Ohio, United States. It is located east of Columbus and had a population of 24,765 as of the 2020 census, down from 25,487 as of the 2010 census. Historically the state capi ...

. He was the second of eight children born to John and Jane (Duke) Hendricks. His father was from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and his mother was from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

.

In 1820 Hendricks moved with his parents and older brother to Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

in Jefferson County, Indiana

Jefferson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2020, the population was 33,147. The county seat is Madison.

History

Jefferson County was formed on February 1, 1811, from Dearborn and Clark Counties. It was named for ...

, at the urging of Thomas's uncle, William Hendricks

William Hendricks (November 12, 1782 – May 16, 1850) was a Democratic-Republican member of the House of Representatives from 1816 to 1822, the third governor of Indiana from 1822 to 1825, and an Anti-Jacksonian member of the U.S. Senate from ...

, a successful politician who served as a U.S. Representative, a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

(1825–37), and as the third governor of Indiana

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state governmen ...

(1822–25). Thomas's family first settled on a farm near his uncle's home in Madison, and moved to Shelby County, Indiana

Shelby County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 44,436. The county seat (and only incorporated city) is Shelbyville.

History

After the American Revolutionary War established US sov ...

, in 1822. Hendricks's father, a successful farmer who operated a general store, became involved in politics, including appointment from President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

as deputy surveyor of public lands for his district. Indiana's Democratic Party leaders frequently visited the Hendricks home in Shelbyville, and from an early age Hendricks was influenced to enter politics.

Hendricks attended local schools (Shelby County Seminary and Greensburg Academy). He graduated from Hanover College

Hanover College is a private college in Hanover, Indiana, affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA). Founded in 1827 by Reverend John Finley Crowe, it is Indiana's oldest private college. The Hanover athletic teams participate in the H ...

in Hanover, Indiana, in 1841, in the same class as Albert G. Porter

Albert Gallatin Porter (April 20, 1824 – May 3, 1897) was an American politician who served as the 19th governor of Indiana from 1881 to 1885 and as a United States Congressman from 1859 to 1863. Originally a Democrat, he joined the Republica ...

, also a future governor of Indiana. After college Hendricks read law with Judge Stephen Major in Shelbyville, and in 1843 he took an eight-month law course at a school operated by his uncle, Judge Alexander Thomson in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and north of Maryland and the ...

. Hendricks returned to Indiana, was admitted to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

in 1843, and established a private practice in Shelbyville.

Marriage and family

Hendricks married Eliza Carol Morgan ofNorth Bend, Ohio

North Bend is a village in Miami Township, Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River. It is a part of the Greater Cincinnati area. The population was 857 at the 2010 census.

History

North Bend was founded in 1789. It was pla ...

, on September 26, 1845, after a two-year courtship. The couple met when Eliza was visiting her married sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Morgan West, in Shelbyville. The couple's only child, a son named Morgan, was born on January 16, 1848, and died in 1851, at the age of three. Thomas and Eliza Hendricks moved to Indianapolis in 1860 and resided from 1865 to 1872 at 1526 South New Jersey Street, now known as the Bates-Hendricks House. See also: In

Early political career

Hendricks remained active in the legal community and in state and national politics from the 1840s until his death in 1885.Indiana legislature and constitutional convention

Hendricks began his political career in 1848, when he served a one-year term in theIndiana House of Representatives

The Indiana House of Representatives is the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The House is composed of 100 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. House me ...

after defeating Martin M. Ray, the Whig candidate. Hendricks was also one of the two Shelby County delegates to the 1850–51 Indiana constitutional convention. He served on committee that created the organization of the state's townships and counties and decided on the taxation and financial portion of the state constitution. Hendricks also debated the clauses on the powers of the different offices and argued in favor of a powerful judiciary and the abolishment of grand juries.

U.S. congressman

Hendricks represented Indiana as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives (1851–55) in the Thirty-second and Thirty-third Congresses from March 4, 1851, to March 3, 1855. Hendricks was chairman of the U.S. Committee on Mileage (Thirty-second Congress) and served on the U.S. Committee on Invalid Pensions (Thirty-third Congress). He supported the principle ofpopular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

and voted in favor of the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

of 1854, which expanded slavery into the western territories of the United States. Both positions were unpopular in Hendricks's home district in Indiana and led to defeat in his re-election bid to Congress in 1854.

Land office commissioner

In 1855 PresidentFranklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

appointed Hendricks as commissioner of the General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an independent agency of the United States government responsible for public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 to take over functions previously conducted by the United States Department o ...

in Washington, D.C. His job supervising 180 clerks and a four-year backlog of work was a demanding one, especially at a time when westward expansion meant that the government was going through one of its largest periods of land sales. During his tenure, the land office issued 400,000 land patents and settled 20,000 disputed land cases. Although Hendricks made thousands of decisions related to disputed land claims, only a few were reversed in court, but he did receive some criticism: "He was the first commissioner who apparently had no background or qualifications for the job. ...Some of the rulings and letters during Hendricks's tenure were not always correct."

Hendricks resigned as land office commissioner in 1859 and returned to Shelby County, Indiana. The cause of his departure was not recorded, but potential reasons may have been differences of opinion with President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, Pierce's successor. Hendricks resisted Buchanan's efforts to make land office clerks patronage positions, objected to the pro-slavery policies of the Buchanan administration, and supported the homestead bill, which Buchanan opposed.

Candidate for Indiana governor

Hendricks ran forgovernor of Indiana

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state governmen ...

three times (1860, 1868, and 1872), and succeeded only on his third attempt. He became the first Democrat to win a gubernatorial seat after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

In 1860 Hendricks, who ran with David Turpie

David Battle Turpie (July 8, 1828 – April 21, 1909) was an American politician who served as a Senator from Indiana from 1887 until 1899; he also served as Chairman of the Senate Democratic Caucus from 1898 to 1899 during the last year of his ...

as his running mate, lost to the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

candidates, Henry Smith Lane

Henry Smith Lane (February 24, 1811 – June 19, 1881) was a United States representative, Senator, and the 13th Governor of Indiana; he was by design the shortest-serving Governor of Indiana, having made plans to resign the office should his ...

and Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

. Three of the four men (Lane, Morton, and Hendricks) eventually served as Indiana's governor, and all four became U.S. senators.

In 1868, his second campaign for Indiana governor, Hendricks lost to Conrad Baker

Conrad Baker (February 12, 1817 – April 28, 1885) was an American attorney, military officer, and politician who served as state representative, 15th lieutenant governor, and the 15th governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1867 to 1873. B ...

, the incumbent, by 961 votes. Baker, who would later become one of Hendricks's law partners, was elected as lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

in 1864, and became governor after Morton was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1867. In the national election, Republican nominees Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

and his running mate, Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the Hous ...

of Indiana, carried the state by a margin of more than 20,000 votes, suggesting that the close race for governor demonstrated Hendricks's popularity in Indiana. Following his defeat in his second gubernatorial race Hendricks retired from the U.S. Senate in March 1869 and returned to his private law practice in Indianapolis, but remained connected to state and national politics.

In 1872, his third campaign to become governor of Indiana, Hendricks narrowly defeated General Thomas M. Browne, 189,424 votes to 188,276.

Law practice

In addition to his years of service in various political offices in Indiana and Washington, D.C., Hendricks maintained an active law practice, which he first established in Shelbyville in 1843 and continued after his relocation to Indianapolis. Hendricks andOscar B. Hord

Oscar B. Hord (August 31, 1829 – January 15, 1888) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the sixth Indiana Attorney General from November 3, 1862 to November 3, 1864.

Biography

Hord was born in 1829 in Maysville, Kentucky. He wa ...

established a law firm in 1862, where Hendricks practiced until the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. Th ...

elected him to represent Indiana in the U.S. Senate in 1863. The law practice was renamed Hendricks, Hord, and Hendricks in 1866, after Abram W. Hendricks

Abram W. Hendricks (October 12, 1822 - January 4, 1887) was an American attorney and politician. He represented Jefferson County, Indiana, in the Indiana House of Representatives for one term and was president of the Indiana State Bar Association ...

joined the firm. In 1873 it was renamed Baker, Hord, and Hendricks, after Conrad Baker, the outgoing governor of Indiana, joined the firm and Hendricks succeeded him as governor. In 1888 the firm passed to Baker's son, who partnered with Edward Daniels, and it became known as Baker & Daniels

Baker & Daniels LLP is a predecessor to the firm Faegre Baker Daniels LLP (now Faegre Drinker), which resulted after the firm merged in 2012 with Minneapolis-based Faegre & Benson. Baker & Daniels counseled clients in transactional, regulato ...

, which grew into one of the state's leading law firms.

High office

U.S. Senator

Hendricks represented Indiana in the U.S. Senate (1863–69) during the final years of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and part of the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

. Military reverses in the Civil War, some unpopular decisions in the Lincoln administration, and Democratic control of the Indiana General Assembly helped Hendricks win election to the U.S. Senate. His six years in the Senate covered the Thirty-eighth, Thirty-ninth, and Fortieth Congresses, where Hendricks was a leader of the small Democratic minority and a member of the opposition who was often overruled.

Hendricks challenged what he thought was radical legislation, including the military draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

and issuing greenbacks; however, he supported the Union and prosecution of the war, consistently voting in favor of wartime appropriations. Hendricks adamantly opposed Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

. After the war he argued that the Southern states had never been out of the Union and were therefore entitled to representation in the U.S. Congress. Hendricks also maintained that Congress had no authority over the affairs of state governments.

Hendricks voted against the Thirteenth

In music or music theory, a thirteenth is the note thirteen scale degrees from the root of a chord and also the interval between the root and the thirteenth. The interval can be also described as a compound sixth, spanning an octa ...

, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth

In music, a fifteenth or double octave, abbreviated ''15ma'', is the interval between one musical note and another with one-quarter the wavelength or quadruple the frequency. It has also been referred to as the bisdiapason. The fourth harmonic, ...

Amendments to the U.S. Constitution that would, upon ratification, grant voting rights to males of all races and abolish slavery. Hendricks felt it was not the right time, so soon after the Civil War, to make fundamental changes to the U.S. Constitution. Although Hendricks supported freedom for African Americans, stating, "He is free; now let him remain free," he unsuccessfully opposed reconstruction legislation. Hendricks did not believe in racial equality. For example, in a congressional debate with Indiana's Senator Oliver Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Ame ...

, Hendricks argued,

Hendricks also opposed the attempt to remove President

Hendricks also opposed the attempt to remove President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

from office following his impeachment in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Hendricks's views were often misinterpreted by his political opponents in Indiana. When the Republicans regained a majority in the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. Th ...

in 1868, the same year Hendricks's U.S. Senate term expired, he lost reelection to a second term, and was succeeded by Republican Congressman-elect Daniel D. Pratt, who resigned the U.S. House seat to which he had been elected in 1868 in order to accept the Senate seat.

Governor of Indiana

In 1872 Hendricks was elected as the governor of Indiana in his third bid for the office. An indication of Hendricks's growing national popularity occurred during the presidential election of 1872; the Democrats nominatedHorace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

, the Liberal Republican candidate. Greeley died soon after the election, but before the Electoral College cast its ballots; 42 of 63 Democratic electors previously pledged to Greeley voted for Hendricks.

Hendricks served as governor of Indiana from January 13, 1873, to January 8, 1877, a difficult period of post-war economic depression following the financial Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

. Indiana experienced high unemployment, business failures, labor strikes, and falling farm prices. Hendricks twice called out the state militia to end workers' strikes, one by miners in Clay County Clay County is the name of 18 counties in the United States. Most are named for Henry Clay, U.S. Senator and statesman:

* Clay County, Alabama

* Clay County, Arkansas (named for John Clayton, and originally named Clayton County)

* Clay County, Flo ...

, and one by railroad workers' in Logansport.

Although Hendricks succeeded in encouraging legislation enacting election and judiciary reform, the Republican-controlled legislature prevented him from achieving many of his other legislative goals. In 1873 Hendricks signed the Baxter bill, a controversial piece of temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

legislation that established a strict form of local option, even though he personally had favored a licensing law. Hendricks signed the legislation because he thought the bill was constitutional and reflected the majority view of the Indiana General Assembly and the will of Indiana's citizens. The law proved to be unenforceable and was repealed in 1875; it was replaced by a licensing system that Hendricks had preferred.

One of Hendricks's lasting legacies during his tenure as governor began with discussion to fund construction of a new Indiana Statehouse

The Indiana Statehouse is the state capitol building of the U.S. state of Indiana. It houses the Indiana General Assembly, the office of the Governor of Indiana, the Indiana Supreme Court, and other state officials. The Statehouse is located in ...

. The existing structure, which had been in use since 1835, had become too small, forcing the growing state government to rent additional buildings around Indianapolis. Besides its size, the dilapidated capitol building was in need of major repair. The roof in the Hall of Representatives had collapsed in 1867 and public inspectors condemned the building in 1873. The cornerstone for the present-day state capital building was laid in 1880, after Hendricks left office, and he delivered the keynote speech at the ceremony. The new statehouse was completed eight years later and remains in use as Indiana's state capitol building.

Vice presidential nominee

Hendricks ran for

Hendricks ran for vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

in 1876 and 1884; he won in 1884. The Democrats also nominated Hendricks for the vice presidency in 1880, but he declined for health reasons. In 1880, while on a visit to Hot Springs, Arkansas, Hendricks suffered a bout of paralysis, but returned to public life. No one outside of his family and doctors knew his health was failing. Two years later he was no longer able to stand.

In the disputed presidential election of 1876

The following elections occurred in the year 1876.

Europe

* 1876 Dalmatian parliamentary election

* 1876 French legislative election

* 1876 Leominster by-election

* 1876 Spanish general election

North America Canada

* 1876 Prince Edward Isl ...

Hendricks ran as the Democratic candidate for vice president with New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

governor Samuel Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden (February 9, 1814 – August 4, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 25th Governor of New York and was the Democratic candidate for president in the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. Tilden was ...

as the party's presidential nominee. Hendricks did not attend the Democratic convention in Saint Louis, but the party was pursuing the strategy of carrying the Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

along with New York and Indiana. The Indiana delegation urged Hendricks as the vice presidential nominee, and he was nominated unanimously.

Although they received the majority of the popular vote, Tilden and Hendricks lost the disputed election by one vote in Electoral College balloting to Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

, the Republican Party's presidential nominee, and William A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler (June 30, 1819June 4, 1887) was an American politician and attorney. He served as a United States representative from New York from 1861 to 1863 and 1869 to 1877, and the 19th vice president of the United States from 1877 t ...

, his vice presidential running mate. A fifteen-member Electoral Commission that included five representatives each from the House, Senate, and U.S. Supreme Court determined the outcome of the contested electoral votes. In an 8 to 7 partisan vote, the commission awarded all twenty of the disputed votes from South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

, and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

to the Republican candidates. Tilden and Hendricks accepted the decision, despite deep disappointment at the outcome.

As chairman of the Indiana delegation, Hendricks attended the Democratic Party's national convention in 1884 in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, where he was again nominated as its vice presidential candidate by a unanimous vote. Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

was the party's presidential nominee in the 1884 presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

; once again the Democrats' strategy was to win New York, Cleveland's home state, and Hendricks's home state of Indiana, plus the electoral votes of the Solid South. Democrats narrowly won New York, Indiana, and two more Northern states plus the Solid South to secure the election.

Vice presidency (1885)

Hendricks, like fellow predecessorWilliam A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler (June 30, 1819June 4, 1887) was an American politician and attorney. He served as a United States representative from New York from 1861 to 1863 and 1869 to 1877, and the 19th vice president of the United States from 1877 t ...

, got along pretty well with the President Grover Cleveland. He really admired Cleveland's character and described him as "courteous and affable". Hendricks, who had been in poor health for several years, served as Cleveland's vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

during the last eight months of his life, from his inauguration on March 4 until his death on November 25, 1885. The vice presidency remained vacant after Hendricks's death until Levi P. Morton

Levi Parsons Morton (May 16, 1824 – May 16, 1920) was the 22nd vice president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He also served as United States ambassador to France, as a U.S. representative from New York, and as the 31st Governor of New ...

assumed office in 1889.

On September 8, 1885, in Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Hendricks made a controversial speech in support of Irish independence. Soon afterwards, Boston machine politician Martin Lomasney

Martin Michael Lomasney (December 3, 1859 – August 12, 1933) was an American Democratic politician from Boston, Massachusetts.

Lomasney served as State Senator, State Representative, and alderman but is best known as the political boss of Bo ...

named the Hendricks Club after him.

Death and legacy

Hendricks died unexpectedly on November 25, 1885, during a trip home to Indianapolis. He complained of feeling ill the morning of November 24, went to bed early, and died in his sleep the following day, aged 66. His reported last words were "Free at last!".

Hendricks's funeral service at Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral in Indianapolis was a large one. Hundreds of dignitaries were in attendance, including President Grover Cleveland, and thousands of people gathered along the city's street to see the 1.2 mile long funeral cortege as it traveled from downtown Indianapolis to

Hendricks died unexpectedly on November 25, 1885, during a trip home to Indianapolis. He complained of feeling ill the morning of November 24, went to bed early, and died in his sleep the following day, aged 66. His reported last words were "Free at last!".

Hendricks's funeral service at Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral in Indianapolis was a large one. Hundreds of dignitaries were in attendance, including President Grover Cleveland, and thousands of people gathered along the city's street to see the 1.2 mile long funeral cortege as it traveled from downtown Indianapolis to Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high point ...

, where his remains were interred.

Hendricks, a popular member of the Democratic Party, remained on good terms with both Democrats and Republicans. He was a fiscal conservative and a powerful orator who was known for his honesty and firm convictions.

Hendricks was one of four vice-presidential candidates from Indiana who were elected during the period 1868 to 1920, when Indiana's electoral votes were critical to winning a national election. (The three other men from Indiana who became U.S. vice presidents during this period were Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the Hous ...

, Charles W. Fairbanks, and Thomas R. Marshall

Thomas Riley Marshall (March 14, 1854 – June 1, 1925) was an American politician who served as the 28th vice president of the United States from 1913 to 1921 under President Woodrow Wilson. A prominent lawyer in Indiana, he became an acti ...

.) Five other men from Indiana, George Washington Julian, Joseph Lane

Joseph "Joe" Lane (December 14, 1801 – April 19, 1881) was an American politician and soldier. He was a state legislator representing Evansville, Indiana, and then served in the Mexican–American War, becoming a general. President James K. ...

, Judge Samuel Williams, John W. Kern

John Worth Kern (December 20, 1849 – August 17, 1917) was a Democratic United States Senator from Indiana. While the title was not official, he is considered to be the first Senate majority leader (and in turn, the first Senate Democratic Lead ...

, and William Hayden English

William Hayden English (August 27, 1822 – February 7, 1896) was an American politician. He served as a U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1853 to 1861 and was the Democratic Party's nominee for Vice President of the United States i ...

, lost their bids for the vice presidency during this time period.

Honors and tributes

* Hendricks remains the only vice president who did not serve as president whose portrait appears on U.S. paper currency. An engraved portrait of Hendricks appears on a $10 "tombstone"

* Hendricks remains the only vice president who did not serve as president whose portrait appears on U.S. paper currency. An engraved portrait of Hendricks appears on a $10 "tombstone" silver certificate A silver certificate is a certificate of ownership that silver owners hold instead of storing the actual silver. Several countries have issued silver certificates, including Cuba, the Netherlands, and the United States. Silver certificates have also ...

. The currency note's nickname is derived from the tombstone-shaped border outlining Hendricks's portrait.

* The Bates-Hendricks House, where the family lived from 1865 to 1872, is located in Indianapolis at 1526 South New Jersey Street, Indianapolis. The home was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

on April 11, 1977.

* Thomas A. Hendricks Library (Hendricks Hall) at Hanover College

Hanover College is a private college in Hanover, Indiana, affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA). Founded in 1827 by Reverend John Finley Crowe, it is Indiana's oldest private college. The Hanover athletic teams participate in the H ...

, which overlooks the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

near Madison, Indiana

Madison is a city in and the county seat of Jefferson County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River. As of the 2010 United States Census its population was 11,967. Over 55,000 people live within of downtown Madison. Madison is the larges ...

, was built in 1903. Hendricks's widow, Eliza, provided funding for the project as a tribute to her late husband, an alumnus of the college. The library was added to the National Register on February 26, 1982. See also: In Portraits of Thomas and Eliza Hendricks hang in the library.

*The Thomas A. Hendricks Monument was installed on the southeast corner of the state capitol building's grounds in 1890. At it is the tallest bronze statue on the statehouse grounds.

*The community of Hendricks, Minnesota, Hendricks in Minnesota and the adjacent lake were named in his honor.

Electoral history

See also

*List of governors of Indiana *Thomas A. Hendricks Monument *Hendricks, West Virginia, a town named after himNotes

References

* * * * * * * * *copy

* * * * * * * *

External links

*"Thomas A. Hendricks: “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was”

Indiana Historical Bureau

Indiana Historical Bureau

Hendricks biography

Biographical Dictionary of Congress

Hendricks obituaries

Indiana Historic Newspaper Digitization Project] * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hendricks, Thomas A. 1819 births 1885 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century vice presidents of the United States Candidates in the 1868 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1872 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1876 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election 1876 United States vice-presidential candidates 1884 United States vice-presidential candidates Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Hanover College alumni Democratic Party governors of Indiana Indiana lawyers People from Shelbyville, Indiana People from Muskingum County, Ohio Democratic Party members of the Indiana House of Representatives Vice presidents of the United States Democratic Party vice presidents of the United States Democratic Party United States senators from Indiana General Land Office Commissioners Cleveland administration cabinet members Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Indiana Politicians from Indianapolis Members of the Odd Fellows