Thescelosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Thescelosaurus'' ( ;

The

The  Other remains of similar animals were found throughout the late 19th century and 20th century. Another well-preserved skeleton from the slightly older

Other remains of similar animals were found throughout the late 19th century and 20th century. Another well-preserved skeleton from the slightly older  In his paper, Morris described a specimen (

In his paper, Morris described a specimen ( Clint Boyd and colleagues published a reassessment of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Bugenasaura'', and ''Parksosaurus'' in 2009, using new cranial material as a starting point. They found that ''Parksosaurus'' was indeed distinct from ''Thescelosaurus'', and that the skull of ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' was essentially the same as a skull found with a postcranial skeleton that matched ''Thescelosaurus''. Because ''B. infernalis'' could not be differentiated from ''Thescelosaurus'', they regarded the genus as a synonym of ''Thescelosaurus'', the species as dubious, and SDSM 7210 as an example of ''T.'' sp. They found that LACM 33542, although fragmentary, was a specimen of ''Thescelosaurus'', and agreed with Morris that the ankle structure was distinct, returning it to ''T. garbanii''. Finally, they noted that another specimen, RSM P.1225.1, differed from ''T. neglectus'' in some anatomical details, and may represent a new species. Thus, ''Thescelosaurus'' per Boyd et al. (2009) is represented by at least two, and possibly three valid species: type species ''T. neglectus'', ''T. garbanii'', and a possible unnamed species. In December

Clint Boyd and colleagues published a reassessment of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Bugenasaura'', and ''Parksosaurus'' in 2009, using new cranial material as a starting point. They found that ''Parksosaurus'' was indeed distinct from ''Thescelosaurus'', and that the skull of ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' was essentially the same as a skull found with a postcranial skeleton that matched ''Thescelosaurus''. Because ''B. infernalis'' could not be differentiated from ''Thescelosaurus'', they regarded the genus as a synonym of ''Thescelosaurus'', the species as dubious, and SDSM 7210 as an example of ''T.'' sp. They found that LACM 33542, although fragmentary, was a specimen of ''Thescelosaurus'', and agreed with Morris that the ankle structure was distinct, returning it to ''T. garbanii''. Finally, they noted that another specimen, RSM P.1225.1, differed from ''T. neglectus'' in some anatomical details, and may represent a new species. Thus, ''Thescelosaurus'' per Boyd et al. (2009) is represented by at least two, and possibly three valid species: type species ''T. neglectus'', ''T. garbanii'', and a possible unnamed species. In December

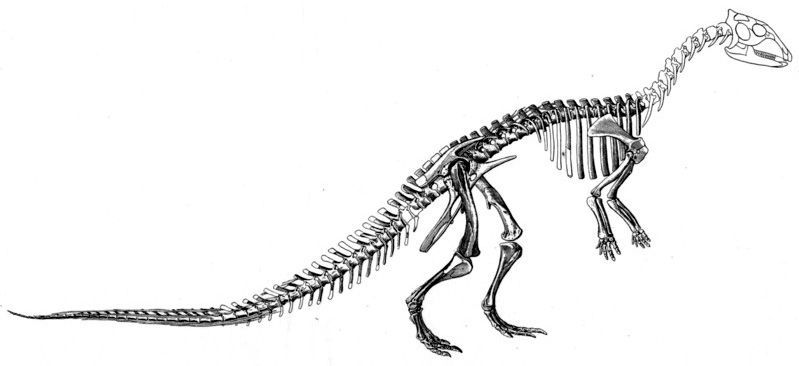

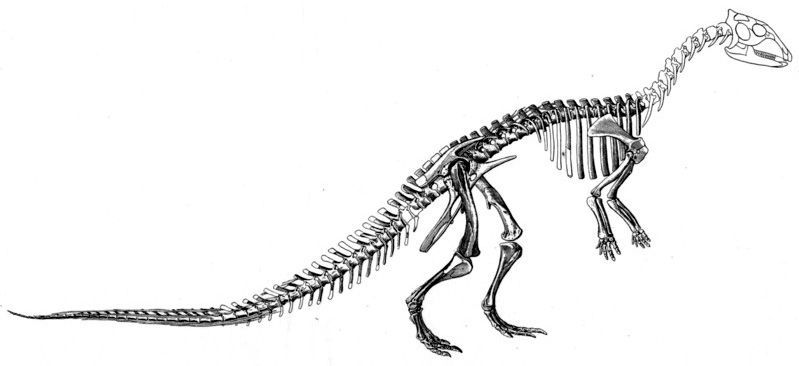

Overall, the skeletal anatomy of this genus is well documented, and restorations have been published in several papers, including skeletal restorations and models. The skeleton is known well enough that a detailed reconstruction of the hip and hindlimb muscles has been made. The animal's size has been estimated in the 2.5–4.0 m range for length (8.2–13.1 ft) for various specimens, and a weight of 200–300

Overall, the skeletal anatomy of this genus is well documented, and restorations have been published in several papers, including skeletal restorations and models. The skeleton is known well enough that a detailed reconstruction of the hip and hindlimb muscles has been made. The animal's size has been estimated in the 2.5–4.0 m range for length (8.2–13.1 ft) for various specimens, and a weight of 200–300  Thescelosaurs had short, broad, five-fingered hands, four-toed feet with

Thescelosaurs had short, broad, five-fingered hands, four-toed feet with

''Thescelosaurus'' has generally been allied to '' Hypsilophodon'' and other small neornithischians as a hypsilophodontid, although recognized as being distinct among them for its robust build, unusual hindlimbs, and, more recently, its unusually long skull.

''Thescelosaurus'' has generally been allied to '' Hypsilophodon'' and other small neornithischians as a hypsilophodontid, although recognized as being distinct among them for its robust build, unusual hindlimbs, and, more recently, its unusually long skull.

''Thescelosaurus'' would have browsed in the first meter or so from the ground, feeding selectively, with food held in the mouth by cheeks while chewing. ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably slower than other hypsilophodonts, because of its heavier build and leg structure. Compared to them, it had unusual hindlimbs, because the upper leg was longer than the shin, the opposite of '' Hypsilophodon'' and running animals in general. One specimen is known to have had a bone pathology, with the long bones of the right foot fused at their tops, hindering swift movement. Examinations of the teeth of ''Thescelosaurus'' and comparisons with the contemporary pachycephalosaur '' Stegoceras'' suggest that ''Thescelosaurus'' was a selective feeder, while ''Stegoceras'' was a more indiscriminate feeder, allowing both animals to share the same environment without competing for food.

''Thescelosaurus'' would have browsed in the first meter or so from the ground, feeding selectively, with food held in the mouth by cheeks while chewing. ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably slower than other hypsilophodonts, because of its heavier build and leg structure. Compared to them, it had unusual hindlimbs, because the upper leg was longer than the shin, the opposite of '' Hypsilophodon'' and running animals in general. One specimen is known to have had a bone pathology, with the long bones of the right foot fused at their tops, hindering swift movement. Examinations of the teeth of ''Thescelosaurus'' and comparisons with the contemporary pachycephalosaur '' Stegoceras'' suggest that ''Thescelosaurus'' was a selective feeder, while ''Stegoceras'' was a more indiscriminate feeder, allowing both animals to share the same environment without competing for food.

In 2000, a skeleton of this genus (specimen NCSM 15728) informally known as "Willo", now on display at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, was described as including the remnants of a four-chambered heart and an

In 2000, a skeleton of this genus (specimen NCSM 15728) informally known as "Willo", now on display at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, was described as including the remnants of a four-chambered heart and an  A study published in 2011 applied multiple lines of inquiry to the question of the object's identity, including more advanced CT scanning,

A study published in 2011 applied multiple lines of inquiry to the question of the object's identity, including more advanced CT scanning,

True ''Thescelosaurus'' remains are known definitely only from late

True ''Thescelosaurus'' remains are known definitely only from late

Conflicting reports have been made as to its preferred

Conflicting reports have been made as to its preferred

''Thescelosaurus''

in the

Willo, the Dinosaur with a Heart

- The official site for "Willo", from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. {{featured article Fossils of Canada Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America Fossil taxa described in 1913 Taxa named by Charles W. Gilmore Lance fauna Hell Creek fauna Scollard fauna Paleontology in South Dakota Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Alberta Laramie Formation Ornithischian genera

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

- (''-'') meaning "godlike", "marvellous", or "wondrous" and (') "lizard") was a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of small neornithischian dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

that appeared at the very end of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

period in North America. It was a member of the last dinosaurian fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

around 66 million years ago. The preservation and completeness of many of its specimens indicate that it may have preferred to live near streams.

This bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

neornithischian is known from several partial skeletons and skulls that indicate it grew to between 2.5 and 4.0 meters (8.2 to 13.1 ft) in length on average. It had sturdy hind limbs, small wide hands, and a head with an elongate pointed snout. The form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form also refers to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter data

* ...

of the teeth and jaws suggest a primarily herbivorous animal. This genus of dinosaur is regarded as a specialized neornithischian, traditionally described as a hypsilophodont, but more recently recognized as distinct from '' Hypsilophodon''. Several species have been suggested for this genus. Three currently are recognized as valid: the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

''T. neglectus'', ''T. garbanii'' and ''T. assiniboiensis''.

The genus attracted media attention in 2000, when a specimen unearthed in 1993 in South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, United States, was interpreted as including a fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ized heart. There was much discussion over whether the remains were of a heart. Many scientists now doubt the identification of the object and the implications of such an identification.

Discovery, history, and species

The

The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

of ''Thescelosaurus'' (USNM

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with ...

7757) was discovered in 1891 by paleontologists John Bell Hatcher and William H. Utterback, from beds

A bed is an item of furniture that is used as a place to sleep, rest, and relax.

Most modern beds consist of a soft, cushioned mattress on a bed frame. The mattress rests either on a solid base, often wood slats, or a sprung base. Many be ...

of the late Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

Lance Formation of Niobrara County (at the time part of Converse County

Converse County is a county located in the U.S. state of Wyoming. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 13,751. Its county seat is Douglas.

History

Converse County was created in 1888 by the legislature of the Wyoming Ter ...

), Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

, USA. The skeleton, however, remained in its shipping crates for years until Charles W. Gilmore of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

's National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7. ...

had it prepared and described it in a short paper in 1913, naming it ''T. neglectus'' (''neglectus'': "neglected"). At the time, he thought it was related to ''Camptosaurus

''Camptosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of plant-eating, beaked ornithischian dinosaurs of the Late Jurassic period of western North America and possibly also Europe. The name means 'flexible lizard' ( Greek (') meaning 'bent' and (') meaning 'li ...

''. He provided a detailed monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

in 1915, describing the well-preserved skeleton. The type specimen was found largely in natural articulation and was missing only the head and neck, which were lost due to erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is d ...

. The name comes from the surprise Gilmore felt at finding such a good specimen that had been unattended to for so long. He considered it to be a light, agile creature, and assigned it to the Hypsilophodontidae, a family of small bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

dinosaurs.

Other remains of similar animals were found throughout the late 19th century and 20th century. Another well-preserved skeleton from the slightly older

Other remains of similar animals were found throughout the late 19th century and 20th century. Another well-preserved skeleton from the slightly older Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of th ...

, in Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest T ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, was named ''T. warreni'' by William Parks in 1926. This skeleton had notable differences from ''T. neglectus'', and so Charles M. Sternberg placed it in a new genus, ''Parksosaurus'', in 1937. Sternberg also named an additional species, ''T. edmontonensis'', based on another articulated skeleton, this time including a partial skull ( NMC 8537), and drew attention to the genus' heavy build and thick bones. Due to these differences from the regular light hypsilophodont build, he suggested that the genus warranted its own subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classifica ...

, Thescelosaurinae

Thescelosaurinae is a subfamily of thescelosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of Asia and the Late Cretaceous of North America.

Distribution

The distribution of Thescelosaurinae is quite large. They are widespread through United States ...

. ''T. edmontonensis'' has, since Peter Galton's 1974 review, generally been considered a more robust individual (possibly the opposite sex of the type individual) of ''T. neglectus''. However, Boyd and colleagues found that they could not assign it to either of their valid species of ''Thescelosaurus'' and regarded the specimen as of uncertain placement within the genus. The other point of contention regarding ''T. edmontonensis'' is its ankle, which Galton claimed was damaged and misinterpreted, but which was regarded by William J. Morris (1976) as truly different from ''T. neglectus''.

In his paper, Morris described a specimen (

In his paper, Morris described a specimen (SDSM

The Social Democratic Union of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалдемократски сојуз на Македонија – СДСМ, ''Socijaldemokratski Sojuz na Makedonija'' – SDSM, sq, Lidhja socialdemokrate e Maqedonisë – LSDM) is a ...

7210) consisting of a partial skull with heavy ridges on the lower jaw and cheek, four partial vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e, and two finger bones as an unidentified species of ''Thescelosaurus'', from the late Maastrichtian-age Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The formation stretches over portions of ...

of Harding County, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, USA. He drew attention to its premaxillary teeth and deeply inset toothline which he interpreted as supporting the presence of muscular cheeks. Morris also pointed out the outwardly flaring premaxilla (which would have given it a wide beak) and large palpebrals. This skull was recognized as an unnamed hypsilophodont for many years, until Galton made it the type specimen of new genus and species ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' ("large-cheeked lizard belonging to the lower regions", ''infernalis'' being a reference to the Hell Creek Formation). Morris also named a new possible species of ''Thescelosaurus'' for specimen LACM

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County is the largest natural and historical museum in the western United States. Its collections include nearly 35 million specimens and artifacts and cover 4.5 billion years of history. This large col ...

33542: ?''T. garbanii'' (with a question mark because he was uncertain that it belonged to the genus). LACM 33542 comprised a large partial hindlimb ("a third larger than described specimens of ''T. neglectus'' and '' Parksosaurus'' or nearly twice as large as '' Hypsilophodon''") including a foot, tarsus, shin bones, and partial thigh bone, along with five cervical (neck) and eleven dorsal (back) vertebrae, from the Hell Creek Formation of Garfield County, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, USA. The specimen was discovered by amateur paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Harley Garbani, hence the name. ''T. garbanii'' would have been about 4.5 meters (15 feet) long, greater than average specimens of ''T. neglectus''. Aside from the size, Morris drew attention to the way the ankle was constructed, which he considered to be unique except in comparison with ''Thescelosaurus edmontonensis'', which he regarded as a separate species. Because Morris believed that the ankles of ''T. garbanii'' compared favorably to those of ''T. edmontonensis'', he tentatively assigned it to ''Thescelosaurus''. However, the scientific literature has favored Galton's view that ''T. edmontonensis'' was not different from ''T. neglectus'' (see above). In the same paper that he described ''Bugenasaura'', Galton demonstrated that the features Morris had thought connected ''T. garbanii'' and ''T. edmontonensis'' were the result of damage to the latter's ankle, so ''T. garbanii'' could also be considered distinct from ''Thescelosaurus''. To better accommodate this species, Galton suggested that it belonged to his new genus ''Bugenasaura'' as ''B. garbanii'', although he also noted that it could be belong to the similarly sized pachycephalosaurid'' Stygimoloch'', or be part of a third, unknown dinosaur.

Clint Boyd and colleagues published a reassessment of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Bugenasaura'', and ''Parksosaurus'' in 2009, using new cranial material as a starting point. They found that ''Parksosaurus'' was indeed distinct from ''Thescelosaurus'', and that the skull of ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' was essentially the same as a skull found with a postcranial skeleton that matched ''Thescelosaurus''. Because ''B. infernalis'' could not be differentiated from ''Thescelosaurus'', they regarded the genus as a synonym of ''Thescelosaurus'', the species as dubious, and SDSM 7210 as an example of ''T.'' sp. They found that LACM 33542, although fragmentary, was a specimen of ''Thescelosaurus'', and agreed with Morris that the ankle structure was distinct, returning it to ''T. garbanii''. Finally, they noted that another specimen, RSM P.1225.1, differed from ''T. neglectus'' in some anatomical details, and may represent a new species. Thus, ''Thescelosaurus'' per Boyd et al. (2009) is represented by at least two, and possibly three valid species: type species ''T. neglectus'', ''T. garbanii'', and a possible unnamed species. In December

Clint Boyd and colleagues published a reassessment of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Bugenasaura'', and ''Parksosaurus'' in 2009, using new cranial material as a starting point. They found that ''Parksosaurus'' was indeed distinct from ''Thescelosaurus'', and that the skull of ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' was essentially the same as a skull found with a postcranial skeleton that matched ''Thescelosaurus''. Because ''B. infernalis'' could not be differentiated from ''Thescelosaurus'', they regarded the genus as a synonym of ''Thescelosaurus'', the species as dubious, and SDSM 7210 as an example of ''T.'' sp. They found that LACM 33542, although fragmentary, was a specimen of ''Thescelosaurus'', and agreed with Morris that the ankle structure was distinct, returning it to ''T. garbanii''. Finally, they noted that another specimen, RSM P.1225.1, differed from ''T. neglectus'' in some anatomical details, and may represent a new species. Thus, ''Thescelosaurus'' per Boyd et al. (2009) is represented by at least two, and possibly three valid species: type species ''T. neglectus'', ''T. garbanii'', and a possible unnamed species. In December 2011

File:2011 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: a protester partaking in Occupy Wall Street heralds the beginning of the Occupy movement; protests against Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who was killed that October; a young man celebrates ...

, RSM P.1225.1 was assigned to its own species, ''Thescelosaurus assiniboiensis''. It was named by Caleb M. Brown, Clint A. Boyd and Anthony P. Russell and is known only from its holotype, a small, articulated and almost complete skeleton from the Frenchman Formation

The Frenchman Formation is stratigraphic unit of Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) age in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It is present in southern Saskatchewan and the Cypress Hills of southeastern Alberta. The formation was defined b ...

(late Maastrichtian stage) of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

. In April 2022, a team of scientific journalists exploring the Tanis fossil site in the U.S. state of North Dakota discovered fossils of creatures that resembled a dinosaur species called thescelosaurus, which was thought to have been swept away by an asteroid that struck Earth's surface 2000 miles from the Tanis fossil site 60 million years ago. Reviewed by Sir David Attenborough, animal legs matching those of plant-eating thescelosaurus dinosaurs were discovered by the scientific journalists, and they appeared to have been raptured off by the waves caused by the asteroid impact.

Description

kilogram

The kilogram (also kilogramme) is the unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI), having the unit symbol kg. It is a widely used measure in science, engineering and commerce worldwide, and is often simply called a kilo colloquially. ...

s (450–660 pounds), with the large type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

of ''T. garbanii'' estimated at 4–4.5 meters (13.1–14.8 feet) long. As discussed more fully under " Discovery, history, and species", it may have been sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, with one sex larger than the other. Juvenile remains are known from several locations, mostly based on teeth.

''Thescelosaurus'' was a heavily built bipedal animal, probably herbivorous, but potentially not. There was a prominent ridge along the length of both maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

e (the tooth-bearing "cheek" bones), and a ridge on both dentaries (tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw). The ridges and position of the teeth, deeply internal to the outside surface of the skull, are interpreted as evidence for muscular cheeks. Aside from the long narrow beak, the skull also had teeth in the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

, or upper beak (a primitive trait among neornithischians). Long rod-like bones called palpebrals were present over the eyes, giving the animal heavy bony eyebrows. Its teeth were of two types: small pointed premaxillary teeth, and leaf-shaped cheek teeth. Six small teeth were present in both premaxillae, with a toothless section at the tip of the beak.

Thescelosaurs had short, broad, five-fingered hands, four-toed feet with

Thescelosaurs had short, broad, five-fingered hands, four-toed feet with hoof

The hoof (plural: hooves) is the tip of a toe of an ungulate mammal, which is covered and strengthened with a thick and horny keratin covering. Artiodactyls are even-toed ungulates, species whose feet have an even number of digits, yet the rum ...

-like toe tips, and a long tail braced by ossified tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough, high-tensile-strength band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It is able to transmit the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system without sacrificing its ability ...

s from the middle to the tip, which would have reduced the flexibility of the tail. The rib cage was broad, giving it a wide back, and the limbs were robust. The animals may have been able to move on all fours

All Fours is a traditional English card game, once popular in pubs and taverns as well as among the gentry, that flourished as a gambling game until the end of the 19th century. It is a trick-taking card game that was originally designed for two ...

, given its fairly long arms and wide hands, but this idea has not been widely discussed in the scientific literature, although it does appear in popular works. Charles M. Sternberg reconstructed it with the upper arm

In human anatomy, the arm refers to the upper limb in common usage, although academically the term specifically means the upper arm between the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and the elbow joint. The distal part of the upper limb between t ...

oriented almost perpendicular to the body, another idea that has gone by the wayside. As noted by Peter Galton

Peter Malcolm Galton (born 14 March 1942 in London) is a British vertebrate paleontologist who has to date written or co-written about 190 papers in scientific journals or chapters in paleontology textbooks, especially on ornithischian and prosa ...

, the upper arm bone of most ornithischians articulated with the shoulder by an articular surface that consisted of the entire end of the bone, instead of a distinct ball and socket as in mammals. The orientation of the shoulder's articular surface also indicates a vertical and not horizontal upper arm in dinosaurs.

Large thin flat mineralized plates have been found next to the ribs' sides. Their function is unknown; they may have played a role in respiration. However, muscle scars or other indications of attachment have not been found for the plates, which argues against a respiratory function. Recent histological study of layered plates from a probable subadult indicates that they may have started as cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck ...

and became bone as the animal aged. Such plates are known from several other cerapodas.

For most of its history, the nature of this genus' integument, be it scales or something else, remained unknown. Charles Gilmore described patches of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

ized material near the shoulders as possible epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rel ...

, with a "punctured" texture, but no regular pattern, while William J. Morris suggested that armor

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or f ...

was present, in the form of small scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

s he interpreted as located at least along the midline of the neck of one specimen. Scutes have not been found with other articulated specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'', though, and Morris's scutes could be crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

n in origin. In his 2022 documentary, '' Dinosaurs: The Final Day'', Sir David Attenborough reported a ''Thescelosaurus'' specimen allegedly killed on the day of the K-Pg extinction, covered in skin impressions that included elongated scales over the legs. One of the paleontologists excavating it was quoted as speculating they had a camouflage function. In a follow-up interview, Paul Barrett has noted that this means ''Thescelosaurus'' was not feathered as hypothesized for other small neornithischians.

Classification

''Thescelosaurus'' has generally been allied to '' Hypsilophodon'' and other small neornithischians as a hypsilophodontid, although recognized as being distinct among them for its robust build, unusual hindlimbs, and, more recently, its unusually long skull.

''Thescelosaurus'' has generally been allied to '' Hypsilophodon'' and other small neornithischians as a hypsilophodontid, although recognized as being distinct among them for its robust build, unusual hindlimbs, and, more recently, its unusually long skull. Peter Galton

Peter Malcolm Galton (born 14 March 1942 in London) is a British vertebrate paleontologist who has to date written or co-written about 190 papers in scientific journals or chapters in paleontology textbooks, especially on ornithischian and prosa ...

in 1974 presented one twist to the classic arrangement, suggesting that because of its hindlimb structure and heavy build (not cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often u ...

, or built for running, by his definition), it should be included in the Iguanodontidae. This has not been followed, with Morris arguing strongly against Galton's classification scheme. At any rate, Galton's Iguanodontidae was polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage of organisms or other evolving elements that is of mixed evolutionary origin. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of conver ...

and not a natural group, and so would not be recognized under modern cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

usage.

Although Hypsilophodontidae was interpreted as a natural group in the early 1990s, this hypothesis has fallen out of favor and Hypsilophodontidae has been found to be an unnatural family composed of a variety of animals more or less closely related to Iguanodontia (paraphyly

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

), with various small clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

s of closely related taxa. "Hypsilophodontidae" and "hypsilophodont" are better understood as informal terms for an evolutionary grade, not a true clade. ''Thescelosaurus'' has been regarded as both very basal and very derived

Derive may refer to:

*Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguation ...

among the hypsilophodonts. One issue that has potentially interfered with classifying ''Thescelosaurus'' is that not all of the remains assigned to ''T. neglectus'' necessarily belong to it. Clint Boyd and colleagues found that while the clade ''Thescelosaurus'' included the genus ''Bugenasaura'' and the species that had been assigned to that genus, there were at least two and possibly three species within ''Thescelosaurus'', and several specimens previously assigned to ''T. neglectus'' could not yet be assigned to a species within the genus. It appears to be closely related to '' Parksosaurus''.

The dissolution of Hypsilophodontidae has been followed by the recognition of the distinct family Thescelosauridae. This area of the dinosaur family tree has historically been complicated by a lack of research, but papers by Clint Boyd and colleagues and Caleb Brown and colleagues have specifically addressed these dinosaurs. Boyd ''et al.'' (2009) and Brown ''et al.'' (2011) found North American "hypsilophodonts" of Cretaceous age to sort into two related clusters, one consisting of '' Orodromeus'', ''Oryctodromeus

''Oryctodromeus'' (meaning "digging runner") was a genus of small orodromine thescelosaurid dinosaur. Fossils are known from the Late Cretaceous Blackleaf Formation of southwestern Montana and the Wayan Formation of southeastern Idaho, USA, bo ...

'', and '' Zephyrosaurus'', and the other consisting of ''Parksosaurus'' and ''Thescelosaurus''. Brown ''et al.'' (2013) recovered similar results, with the addition of the new genus ''Albertadromeus

''Albertadromeus'' is an extinct genus of orodromine thescelosaurid dinosaur known from the upper part of the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation (middle Campanian stage) of Alberta, Canada. It contains a single species, ''Albertadromeus syntars ...

'' to the ''Orodromeus'' clade and several long-snouted Asian forms (previously described under Jeholosauridae) to the ''Thescelosaurus'' clade. They also formally defined Thescelosauridae (''Thescelosaurus neglectus'', ''Orodromeus makelai'', their most recent common ancestor, and all descendants) and the smaller clades Orodrominae and Thescelosaurinae. The below cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

is that of Brown ''et al.''.

Paleobiology

''Thescelosaurus'' would have browsed in the first meter or so from the ground, feeding selectively, with food held in the mouth by cheeks while chewing. ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably slower than other hypsilophodonts, because of its heavier build and leg structure. Compared to them, it had unusual hindlimbs, because the upper leg was longer than the shin, the opposite of '' Hypsilophodon'' and running animals in general. One specimen is known to have had a bone pathology, with the long bones of the right foot fused at their tops, hindering swift movement. Examinations of the teeth of ''Thescelosaurus'' and comparisons with the contemporary pachycephalosaur '' Stegoceras'' suggest that ''Thescelosaurus'' was a selective feeder, while ''Stegoceras'' was a more indiscriminate feeder, allowing both animals to share the same environment without competing for food.

''Thescelosaurus'' would have browsed in the first meter or so from the ground, feeding selectively, with food held in the mouth by cheeks while chewing. ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably slower than other hypsilophodonts, because of its heavier build and leg structure. Compared to them, it had unusual hindlimbs, because the upper leg was longer than the shin, the opposite of '' Hypsilophodon'' and running animals in general. One specimen is known to have had a bone pathology, with the long bones of the right foot fused at their tops, hindering swift movement. Examinations of the teeth of ''Thescelosaurus'' and comparisons with the contemporary pachycephalosaur '' Stegoceras'' suggest that ''Thescelosaurus'' was a selective feeder, while ''Stegoceras'' was a more indiscriminate feeder, allowing both animals to share the same environment without competing for food.

Supposed fossilized heart

In 2000, a skeleton of this genus (specimen NCSM 15728) informally known as "Willo", now on display at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, was described as including the remnants of a four-chambered heart and an

In 2000, a skeleton of this genus (specimen NCSM 15728) informally known as "Willo", now on display at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, was described as including the remnants of a four-chambered heart and an aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

. It had been originally unearthed in 1993 in northwestern South Dakota. The authors had found the internal detail through computed tomography (CT) imagery. They suggested that the heart had been saponified

Saponification is a process of converting esters into soaps and alcohols by the action of aqueous alkali (for example, aqueous sodium hydroxide solutions). Soaps are salts of fatty acids, which in turn are carboxylic acids with long carbon chain ...

(turned to grave wax) under airless burial conditions, and then changed to goethite

Goethite (, ) is a mineral of the diaspore group, consisting of iron(III) oxide-hydroxide, specifically the "α" polymorph. It is found in soil and other low-temperature environments such as sediment. Goethite has been well known since ancient t ...

, an iron mineral, by replacement of the original material. The authors interpreted the structure of the heart as indicating an elevated metabolic rate

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

for ''Thescelosaurus'', not reptilian cold-bloodedness.

Their conclusions have been disputed; soon after the initial description, other researchers published a paper where they asserted that the heart is really a concretion

A concretion is a hard, compact mass of matter formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular ...

. As they noted, the anatomy given for the object is incorrect (for example, the "aorta" narrows coming into the "heart" and lacks arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

coming from it), it partially engulfs one of the ribs and has an internal structure of concentric layers in some places, and another concretion is preserved behind the right leg. The original authors defended their position; they agreed that it was a type of concretion, but one that had formed around and partially preserved the more muscular portions of the heart and aorta.

A study published in 2011 applied multiple lines of inquiry to the question of the object's identity, including more advanced CT scanning,

A study published in 2011 applied multiple lines of inquiry to the question of the object's identity, including more advanced CT scanning, histology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures v ...

, X-ray diffraction

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) is a surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique based on the photoelectric effect that can identify the elements that exist within a material (elemental composition) or are covering its surface, ...

, and scanning electron microscopy. From these methods, the authors found the following: the object's internal structure does not include chambers but is made up of three unconnected areas of lower density material, and is not comparable to the structure of an ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds of the genus ''Struthio'' in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infra-class Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that includes the emus, rheas, and kiwis. There ...

's heart; the "walls" are composed of sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

minerals not known to be produced in biological systems, such as goethite, feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagioclase'' (sodium-calcium) felds ...

minerals, quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical f ...

, and gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywa ...

, as well as some plant fragments; carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, and phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

, chemical elements important to life, were lacking in their samples; and cardiac cellular structures were absent. There was one possible patch with animal cellular structures. The authors found their data supported identification as a concretion of sand from the burial environment, not the heart, with the possibility that isolated areas of tissues were preserved.

The question of how this find reflects metabolic rate and dinosaur internal anatomy is moot, though, regardless of the object's identity. Both modern crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

ns and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s, the closest living relatives of non-avian dinosaurs, have four-chambered hearts (albeit modified in crocodilians), so non-avian dinosaurs probably had them as well; the structure is not necessarily tied to metabolic rate.Chinsamy, Anusuya; and Hillenius, Willem J. (2004). "Physiology of nonavian dinosaurs". ''The Dinosauria'', 2nd ed. 643–659.

Paleoecology

Temporal and geographic range

True ''Thescelosaurus'' remains are known definitely only from late

True ''Thescelosaurus'' remains are known definitely only from late Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian () is, in the ICS geologic timescale, the latest age (uppermost stage) of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series, the Cretaceous Period or System, and of the Mesozoic Era or Erathem. It spanned the inte ...

-age rocks, from Alberta (Scollard Formation

The Scollard Formation is an Upper Cretaceous to lower Palaeocene stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. Its deposition spanned the time interval from latest Cretaceous to early Paleocene, and it inclu ...

) and Saskatchewan (Frenchman Formation

The Frenchman Formation is stratigraphic unit of Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) age in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It is present in southern Saskatchewan and the Cypress Hills of southeastern Alberta. The formation was defined b ...

), Canada, and Wyoming ( Lance Formation), South Dakota (Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The formation stretches over portions of ...

), Montana (Hell Creek), and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

( Laramie Formation), USA. With the exception of birds, it was one of the last genera of dinosaurs, its remains being found as close as 3 meters to the boundary clay containing the iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density o ...

layer that closes the Cretaceous. The Laramie Formation is the oldest formation that ''Thescelosaurus'' is known from, and magnetostratigraphy suggests an age of 69-68 Ma for the Laramie Formation.*Hicks, J.F., Johnson, K.R., Obradovich, J. D., Miggins, D.P., and Tauxe, L. 2003. Magnetostratigraphyof Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to lower Eocene strata of the Denver Basin, Colorado. In K.R. Johnson, R.G. Raynolds and M.L. Reynolds (eds), Paleontology and Stratigraphy of Laramide Strata in the Denver Basin, Pt. II., Rocky Mountain Geology 38: 1-27. There are reports of teeth from older, Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous Epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campani ...

-age rocks, particularly from the Dinosaur Park Formation

The Dinosaur Park Formation is the uppermost member of the Belly River Group (also known as the Judith River Group), a major geologic unit in southern Alberta. It was deposited during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, between about 76. ...

of Alberta, but these specimens are not from ''Thescelosaurus'' and are much more likely those of '' Orodromeus''. More specimens are known than have been officially described for this genus, such as the Triebold specimen, which has been the source of several skeletal casts for museums.

When Galton revisited ''Thescelosaurus'' and ''Bugenasaura'' in 1999, he described the dentary tooth UCMP

The University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) is a paleontology museum located on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley.

The museum is within the Valley Life Sciences Building (VLSB), designed by George W. Kelham and ...

46911 from the Upper Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

of Weymouth, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

as cf. ''Bugenasaura''. If it is indeed a tooth from a thescelosaur-like animal, this would significantly extend the stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostra ...

range of the group.

Habitat

Conflicting reports have been made as to its preferred

Conflicting reports have been made as to its preferred habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

; two papers suggest it preferred channels to floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

s,Pearson, Dean A.; Schaefer, Terry; Johnson, Kirk R.; Nichols, Douglas J.; and Hunter, John P. (2002). "Vertebrate biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek Formation in southwestern North Dakota and northwestern South Dakota". ''The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary Boundary in the Northern Great Plains: An Integrated Continental Record of the End of the Cretaceous.'' 145–167. but another suggests it preferred the opposite. The possible preference for channels is based on the relative abundance of thescelosaur fossils in sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

s, representing channel environments, in comparison to mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.' ...

s, representing floodplain environments. No bonebeds or accumulations of multiple individuals have yet been reported. Dale Russell, in a popular work, noted that ''Thescelosaurus'' was the most common small herbivore in the Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The formation stretches over portions of ...

of the Fort Peck area. He described the environment of the time as a flat floodplain, with a relatively dry subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical and climate zones to the north and south of the tropics. Geographically part of the temperate zones of both hemispheres, they cover the middle latitudes from to approximately 35° north a ...

climate that supported a variety of plants ranging from angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants ...

trees, to bald cypress

''Taxodium distichum'' (bald cypress, swamp cypress; french: cyprès chauve;

''cipre'' in Louisiana) is a deciduous conifer in the family Cupressaceae. It is native to the southeastern United States. Hardy and tough, this tree adapts to a wide ...

, to fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes exce ...

s and ginkgo

''Ginkgo'' is a genus of non-flowering seed plants. The scientific name is also used as the English name. The order to which it belongs, Ginkgoales, first appeared in the Permian, 270 million years ago, and is now the only living genus with ...

s. Although most dinosaur skeletons from this area are incomplete, possibly due to the low preservation potential of forests, ''Thescelosaurus'' skeletons are much more complete, suggesting that this genus frequented stream channels. Thus when a ''Thescelosaurus'' died, it may have been in or near a river, making it easier to bury and preserve for later fossilization. Russell tentatively compared it to the capybara

The capybaraAlso called capivara (in Brazil), capiguara (in Bolivia), chigüire, chigüiro, or fercho (in Colombia and Venezuela), carpincho (in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay) and ronsoco (in Peru). or greater capybara (''Hydrochoerus hydro ...

s and tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inh ...

s.

Other dinosaurs that shared its time and place include the ceratopsids

Ceratopsidae (sometimes spelled Ceratopidae) is a family of ceratopsian dinosaurs including ''Triceratops'', ''Centrosaurus'', and ''Styracosaurus''. All known species were quadrupedal herbivores from the Upper Cretaceous. All but one species ar ...

''Triceratops

''Triceratops'' ( ; ) is a genus of herbivorous chasmosaurine ceratopsid dinosaur that first appeared during the late Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 68 million years ago in what is now North America. It is one ...

'' and '' Torosaurus'', hadrosaurid ''Edmontosaurus

''Edmontosaurus'' ( ) (meaning "lizard from Edmonton") is a genus of hadrosaurid (duck-billed) dinosaur. It contains two known species: ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' and '' Edmontosaurus annectens''. Fossils of ''E. regalis'' have been found in rock ...

'', ankylosaurid ''Ankylosaurus

''Ankylosaurus'' is a genus of armored dinosaur. Its fossils have been found in geological formations dating to the very end of the Cretaceous Period, about 68–66 million years ago, in western North America, making it among the last of th ...

'', pachycephalosaurian ''Pachycephalosaurus

''Pachycephalosaurus'' (; meaning "thick-headed lizard", from Greek ''pachys-/'' "thick", ''kephale/'' "head" and ''sauros/'' "lizard") is a genus of pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs. The type species, ''P. wyomingensis'', is the only known specie ...

'', and the theropods '' Ornithomimus'', '' Troodon'', and ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosa ...

''.Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". ''The Dinosauria'' (2nd). 517–606. ''Thescelosaurus'' was also abundant in the Lance Formation. Toe bones from this genus are the most common finds after fossils of ''Triceratops'' and ''Edmontosaurus'', and it may have been the most common dinosaur there in life, if the Lance Formation had a preservational bias against small animals.

References

External links

''Thescelosaurus''

in the

Paleobiology Database

The Paleobiology Database is an online resource for information on the distribution and classification of fossil animals, plants, and microorganisms.

History

The Paleobiology Database (PBDB) originated in the NCEAS-funded Phanerozoic Marine Pal ...

.

Willo, the Dinosaur with a Heart

- The official site for "Willo", from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. {{featured article Fossils of Canada Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America Fossil taxa described in 1913 Taxa named by Charles W. Gilmore Lance fauna Hell Creek fauna Scollard fauna Paleontology in South Dakota Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Alberta Laramie Formation Ornithischian genera