Theory of imperialism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The theory of imperialism refers to a range of theoretical approaches to understanding the expansion of

While most theories of imperialism are associated with

While most theories of imperialism are associated with

/ref> In ''The History of the Russian Revolution'', published in 1932, Trotsky tied his theory of development to a theory of imperialism. In Trotsky's theory of imperialism, the domination of one country by another does not mean that the dominated country is prevented from development altogether, but rather that it develops mainly according to the requirements of the dominating country. Trotsky's later writings show that uneven and combined development is less of a theory of

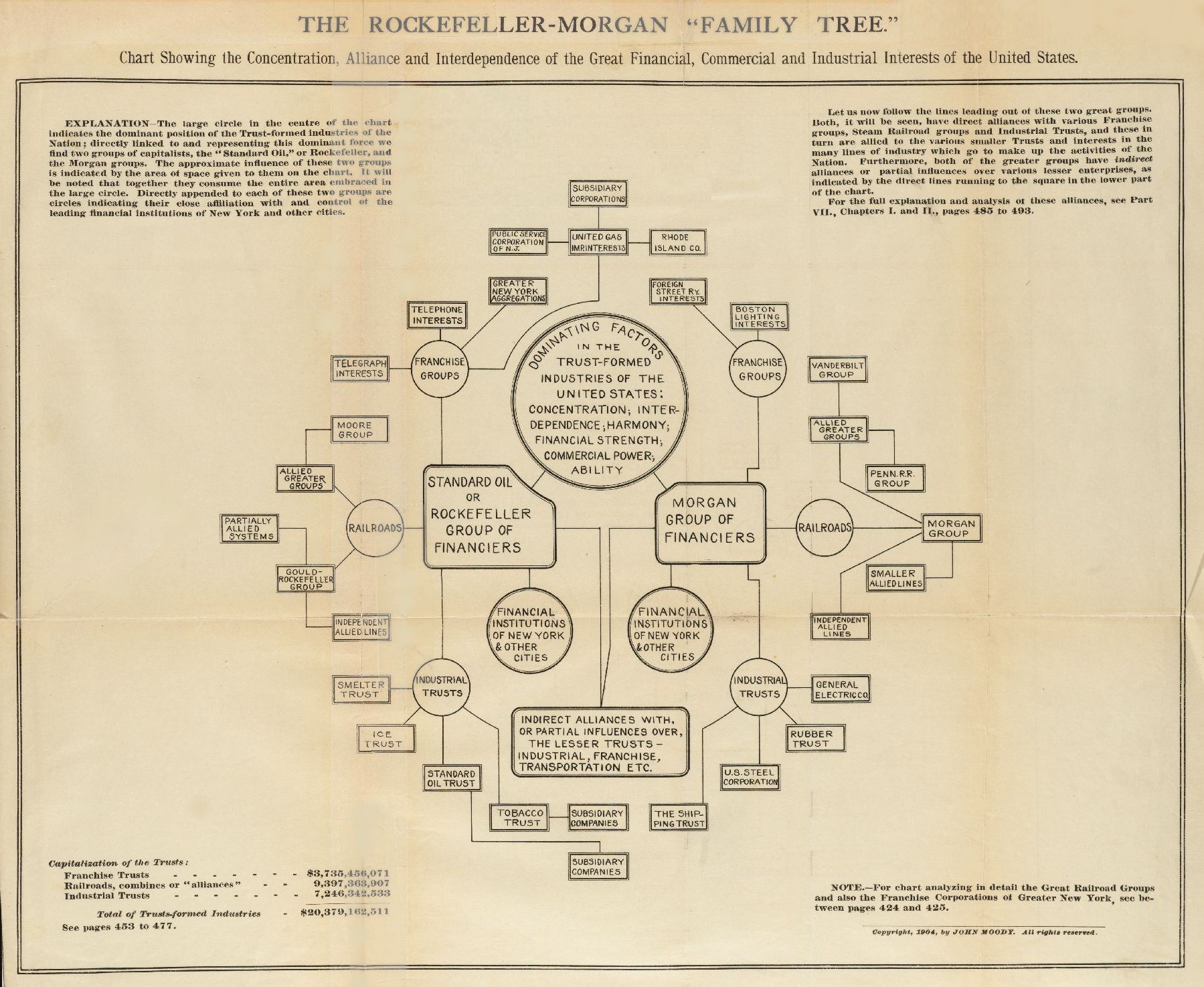

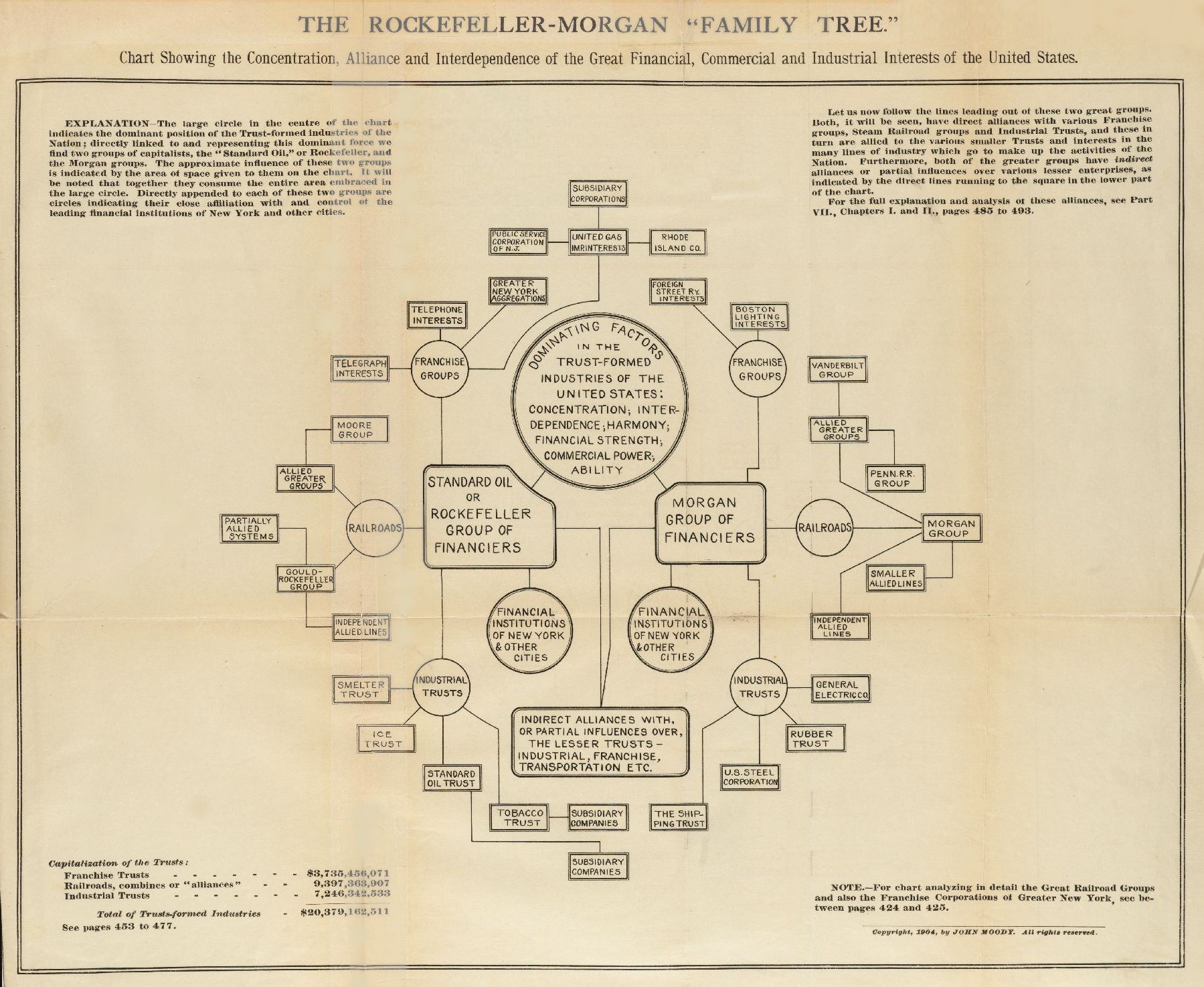

Rudolf Hilferding's ''Finance Capital'', published in 1910, is considered the first of the "classical" Marxist theories of imperialism which would be codified and popularized by

Rudolf Hilferding's ''Finance Capital'', published in 1910, is considered the first of the "classical" Marxist theories of imperialism which would be codified and popularized by  Hilferding's finance capital is best understood as a fraction of capital in which the functions of

Hilferding's finance capital is best understood as a fraction of capital in which the functions of

Prior to the

Prior to the

Ultra-imperialism

'. Kautsky's idea is often best remembered for Lenin's frequent criticism of the concept. In an introduction to Bukharin's ''Imperialism and World Economy'' for example, Lenin contended that "in the abstract one can think of such a phase. In practice, however, he who denies the sharp tasks of to-day in the name of dreams about soft tasks of the future becomes an opportunist". Despite being sharply criticized in its own day, ultra-imperialism has been revived to describe instances of inter-imperialist cooperation in later years, such as cooperation among

Lenin, Kautsky and "ultra-imperialism"

',

Nikolai Bukharin's ''Imperialism and World Economy'', written in 1915, primarily served to clarify and refine the earlier ideas of Hilferding, and frame them in a more consistently

Nikolai Bukharin's ''Imperialism and World Economy'', written in 1915, primarily served to clarify and refine the earlier ideas of Hilferding, and frame them in a more consistently

Despite being a relatively small text which sought only to summarize the earlier ideas of Hobson, Hilferdung and Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet '' Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'' is easily the most influential, widely read text on the subject of imperialism.

Lenin's argument differs from previous writers in that rather than viewing imperialism as a distinct

Despite being a relatively small text which sought only to summarize the earlier ideas of Hobson, Hilferdung and Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet '' Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'' is easily the most influential, widely read text on the subject of imperialism.

Lenin's argument differs from previous writers in that rather than viewing imperialism as a distinct

Between the publication of Lenin's ''Imperialism'' in 1916 and Paul Sweezy's ''The Theory of Capitalist Development'' in 1942 and Paul A. Baran's ''Political Economy of Growth'' in 1957, there was a notable lack of development in the Marxist theory of imperialism, best explained by the elevation of Lenin's work to the status of Marxist orthodoxy. Like Hobson, Baran and Sweezy employed an underconsumptionist line of reasoning to argue that infinite growth of the capitalist system is impossible. They argued that as capitalism develops, wages tend to decline, and with them, the total level of consumption. The ability for consumption to absorb the total productive output of society is therefore limited, and this output must then be reinvested elsewhere. Since Sweezy implies that it would be impossible to continuously reinvest in productive machinery (which would only increase the output of consumer goods, adding to the initial problem), there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the need to increase investments to absorb surplus output, and the need to reduce overall output to match consumer demand. This problem can, however, be delayed through investments in unproductive aspects of society (such as the military), or through capital export.

Between the publication of Lenin's ''Imperialism'' in 1916 and Paul Sweezy's ''The Theory of Capitalist Development'' in 1942 and Paul A. Baran's ''Political Economy of Growth'' in 1957, there was a notable lack of development in the Marxist theory of imperialism, best explained by the elevation of Lenin's work to the status of Marxist orthodoxy. Like Hobson, Baran and Sweezy employed an underconsumptionist line of reasoning to argue that infinite growth of the capitalist system is impossible. They argued that as capitalism develops, wages tend to decline, and with them, the total level of consumption. The ability for consumption to absorb the total productive output of society is therefore limited, and this output must then be reinvested elsewhere. Since Sweezy implies that it would be impossible to continuously reinvest in productive machinery (which would only increase the output of consumer goods, adding to the initial problem), there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the need to increase investments to absorb surplus output, and the need to reduce overall output to match consumer demand. This problem can, however, be delayed through investments in unproductive aspects of society (such as the military), or through capital export.

In addition to this underconsumptionist argument, Baran and Sweezy argued that there are two motives for investment in industry: increasing productive output, and introducing new productive techniques. While in conventional competitive capitalism, any firm which does not introduce new productive techniques will usually fall behind and become unprofitable, in monopoly capitalism, there is actually no incentive to introduce new productive techniques, as there are no rivals to gain a competitive advantage over, and thus no reason to render one's own machinery obsolete. This is a key difference with the earlier "classical" theories of imperialism, especially Bukharin, as here monopoly does not represent an intensification of competition but rather its total suppression. Baran and Sweezy also rejected the earlier claim that all national industries would form a single "national cartel," instead noting that there tended to be a number of monopoly companies within a country: just enough to maintain a "balance of power."

The connection to imperialist violence then, is that most western nations have sought to solve their underconsumption crises by investing heavily into military armaments, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In addition to this, capital exports into the less concretely divided areas of the world have increased, and monopoly companies seek protection from their parent states in order to secure these foreign investments. To Baran and Sweezy, these two factors explain imperialist warfare and the dominance of developed countries.

Conversely, they explain the underdevelopment of poor nations through trade flows. Trade flows serve to provide cheap primary goods to the advanced countries, while local manufacturing in underdeveloped countries is discouraged through competition with goods from the advanced countries. Baran and Sweezy were the first economists to treat the development of capitalism in the advanced countries as different from its development in the underdeveloped countries, an outlook influenced by the philosophy of

In addition to this underconsumptionist argument, Baran and Sweezy argued that there are two motives for investment in industry: increasing productive output, and introducing new productive techniques. While in conventional competitive capitalism, any firm which does not introduce new productive techniques will usually fall behind and become unprofitable, in monopoly capitalism, there is actually no incentive to introduce new productive techniques, as there are no rivals to gain a competitive advantage over, and thus no reason to render one's own machinery obsolete. This is a key difference with the earlier "classical" theories of imperialism, especially Bukharin, as here monopoly does not represent an intensification of competition but rather its total suppression. Baran and Sweezy also rejected the earlier claim that all national industries would form a single "national cartel," instead noting that there tended to be a number of monopoly companies within a country: just enough to maintain a "balance of power."

The connection to imperialist violence then, is that most western nations have sought to solve their underconsumption crises by investing heavily into military armaments, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In addition to this, capital exports into the less concretely divided areas of the world have increased, and monopoly companies seek protection from their parent states in order to secure these foreign investments. To Baran and Sweezy, these two factors explain imperialist warfare and the dominance of developed countries.

Conversely, they explain the underdevelopment of poor nations through trade flows. Trade flows serve to provide cheap primary goods to the advanced countries, while local manufacturing in underdeveloped countries is discouraged through competition with goods from the advanced countries. Baran and Sweezy were the first economists to treat the development of capitalism in the advanced countries as different from its development in the underdeveloped countries, an outlook influenced by the philosophy of

Emmanuel based his theory on a close reading of Marx's writings on price, factors of production and wages. He concurred with

Emmanuel based his theory on a close reading of Marx's writings on price, factors of production and wages. He concurred with

Immanuel Wallerstein argued that any system must be viewed as a totality, and that most theories of imperialism had hitherto incorrectly treated individual states as closed systems. Instead, from the 16th century onwards a world-system formed through market exchange had developed, displacing the "minisystems" (small, local economies) and "world-empires" (systems based on tribute to a central authority) that had existed until that point. Wallerstein did not treat capitalism as a discrete mode of production, but rather as the "indivisible phenomenon" behind the world-system.

The world-system is divided into three tiers of states, the core, the periphery, and the

Immanuel Wallerstein argued that any system must be viewed as a totality, and that most theories of imperialism had hitherto incorrectly treated individual states as closed systems. Instead, from the 16th century onwards a world-system formed through market exchange had developed, displacing the "minisystems" (small, local economies) and "world-empires" (systems based on tribute to a central authority) that had existed until that point. Wallerstein did not treat capitalism as a discrete mode of production, but rather as the "indivisible phenomenon" behind the world-system.

The world-system is divided into three tiers of states, the core, the periphery, and the

Samir Amin's main contributions to the study of imperialism are his theories of "accumulation on a world scale" and of "unequal development." To Amin, the process of accumulation must be understood on a world scale, but in a world divided into distinct national social formations. The process of accumulation tends to exacerbate inequalities between these social formations, whereupon they become divided into a core and periphery. Accumulation within the center tends to be "autocentric," or governed by its own internal dynamic as dictated by local conditions, prices, and effective demand, in a manner relatively unchanged since it was first described by Marx. Accumulation in the periphery, on the other hand, is "extraverted," meaning that it is conducted in a manner beneficial to core countries, dictated by their need for goods and raw materials. This extraverted accumulation results in export specialization, with a large proportion of developing economies devoted to producing goods to suit foreign demand.

Amin thought that this imperialist dynamic could be overcome by a process of "de-linking" economies which would sever developing economies from the global law of value, allowing them to decide on a "national law of value." This would allow something approaching autocentric accumulation in poorer countries, for example allowing rural communities to move towards

Samir Amin's main contributions to the study of imperialism are his theories of "accumulation on a world scale" and of "unequal development." To Amin, the process of accumulation must be understood on a world scale, but in a world divided into distinct national social formations. The process of accumulation tends to exacerbate inequalities between these social formations, whereupon they become divided into a core and periphery. Accumulation within the center tends to be "autocentric," or governed by its own internal dynamic as dictated by local conditions, prices, and effective demand, in a manner relatively unchanged since it was first described by Marx. Accumulation in the periphery, on the other hand, is "extraverted," meaning that it is conducted in a manner beneficial to core countries, dictated by their need for goods and raw materials. This extraverted accumulation results in export specialization, with a large proportion of developing economies devoted to producing goods to suit foreign demand.

Amin thought that this imperialist dynamic could be overcome by a process of "de-linking" economies which would sever developing economies from the global law of value, allowing them to decide on a "national law of value." This would allow something approaching autocentric accumulation in poorer countries, for example allowing rural communities to move towards

Post-Marxists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri introduced a new theory of imperialism with their book ''Empire'', published in 2000. Drawing on an eclectic set of inspirations including Newton,

Post-Marxists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri introduced a new theory of imperialism with their book ''Empire'', published in 2000. Drawing on an eclectic set of inspirations including Newton,

Topics in recent studies of imperialism include the role of debt in imperialism, reappraisals of earlier theorists, the introduction of political ecology to the study of imperial borders, and the synthesis of imperialism and ecological studies into the theory of ecologically unequal exchange.

Econometric studies of the past or ongoing effects of imperialism on the Global South, such as the work of

Topics in recent studies of imperialism include the role of debt in imperialism, reappraisals of earlier theorists, the introduction of political ecology to the study of imperial borders, and the synthesis of imperialism and ecological studies into the theory of ecologically unequal exchange.

Econometric studies of the past or ongoing effects of imperialism on the Global South, such as the work of

Most theorists of imperialism agree that monopolies are in some way connected to the growth of imperialism. In most theories, "monopoly" is used in a different manner to the conventional use of the word. Rather than referring to a total control over the supply of a particular commodity, monopolization refers to any general tendency towards larger companies, which win out against smaller competitors within a country.

"Monopoly capital," sometimes called "finance capital," refers to the specific kind of capital which such companies wield, in which the functions of financial (or banking) capital and industrial capital become merged. Such capital can both be raised or loaned from an indefinite number of sources, and also be reinvested into a productive cycle.

Depending on the theory, monopolization can either refer to an intensification of competition, a suppression of competition, or a suppression on a national level but intensification on a global level. All of these can lead to imperialist policies, either by widening the scope of competition to include competition between international blocs, by reducing competition to allow for national cooperation, or by reducing competition within poorer areas owned by a monopoly to such a degree that development is impossible. Once they have expanded, monopolies are typically held to gather superprofits in some way, such as through imposing tariffs, protections, or monopoly-rents.

The use of the term "monopoly" has been criticized as confusing by some authors, such as Wallerstein who preferred the term "quasi-monopoly" to refer to such phenomena, since he did not believe they were true hegemonies. Classical theories of imperialism have also been criticized for overstating the degree to which monopolies had won out against smaller competitors. Some theories of imperialism also hold that small-scale competitors are perfectly capable of extracting superprofits through unequal exchange.

Most theorists of imperialism agree that monopolies are in some way connected to the growth of imperialism. In most theories, "monopoly" is used in a different manner to the conventional use of the word. Rather than referring to a total control over the supply of a particular commodity, monopolization refers to any general tendency towards larger companies, which win out against smaller competitors within a country.

"Monopoly capital," sometimes called "finance capital," refers to the specific kind of capital which such companies wield, in which the functions of financial (or banking) capital and industrial capital become merged. Such capital can both be raised or loaned from an indefinite number of sources, and also be reinvested into a productive cycle.

Depending on the theory, monopolization can either refer to an intensification of competition, a suppression of competition, or a suppression on a national level but intensification on a global level. All of these can lead to imperialist policies, either by widening the scope of competition to include competition between international blocs, by reducing competition to allow for national cooperation, or by reducing competition within poorer areas owned by a monopoly to such a degree that development is impossible. Once they have expanded, monopolies are typically held to gather superprofits in some way, such as through imposing tariffs, protections, or monopoly-rents.

The use of the term "monopoly" has been criticized as confusing by some authors, such as Wallerstein who preferred the term "quasi-monopoly" to refer to such phenomena, since he did not believe they were true hegemonies. Classical theories of imperialism have also been criticized for overstating the degree to which monopolies had won out against smaller competitors. Some theories of imperialism also hold that small-scale competitors are perfectly capable of extracting superprofits through unequal exchange.

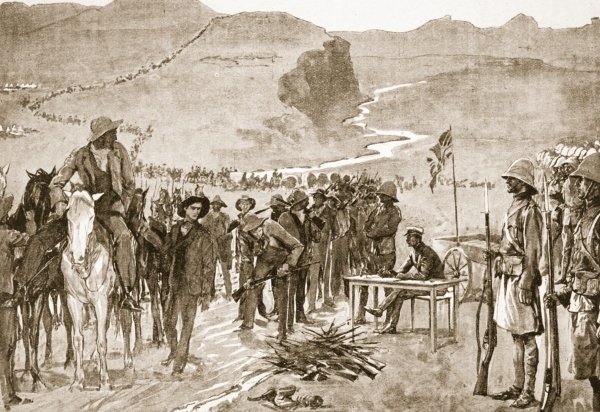

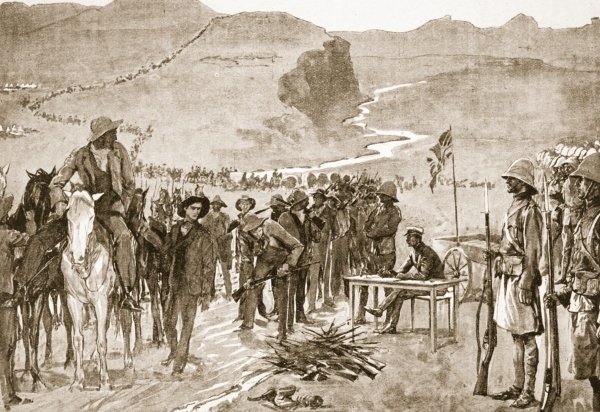

The theory of imperialism is the basis of most

The theory of imperialism is the basis of most  An alternative underconsumptionist explanation of colonialism is that capitalist nations require colonial areas as a dumping ground for consumer goods, although there are greater empirical problems with this view. Finally, the creation of a social-imperialist ideological camp led by a labor aristocracy tends to erode working class opposition to wars, usually by arguing that warfare benefits workers or foreign peoples in some way.

An alternative to this view is that the tendency for the rate of profit to fall is itself enough of a motive for warfare and colonialism, as a rising organic composition of capital in the core countries will lead to a crisis of profitability in the long run. This then necessitates the conquest or colonization of underdeveloped areas with a low organic composition of capital and thus a higher profitability.

Yet another explanation, which is more common in unequal exchange and world-systems theories, is that warfare and colonialism is used to assert the power of core countries, divide the world into areas with different wages or levels of development, and strengthen boundaries to limit

An alternative underconsumptionist explanation of colonialism is that capitalist nations require colonial areas as a dumping ground for consumer goods, although there are greater empirical problems with this view. Finally, the creation of a social-imperialist ideological camp led by a labor aristocracy tends to erode working class opposition to wars, usually by arguing that warfare benefits workers or foreign peoples in some way.

An alternative to this view is that the tendency for the rate of profit to fall is itself enough of a motive for warfare and colonialism, as a rising organic composition of capital in the core countries will lead to a crisis of profitability in the long run. This then necessitates the conquest or colonization of underdeveloped areas with a low organic composition of capital and thus a higher profitability.

Yet another explanation, which is more common in unequal exchange and world-systems theories, is that warfare and colonialism is used to assert the power of core countries, divide the world into areas with different wages or levels of development, and strengthen boundaries to limit

Most earlier writers on imperialism favored the view that imperialism had a contradictory effect on colonized nations’ development, simultaneously building up their productive forces, better integrating them into a world economy and providing education, while also bringing warfare, economic exploitation, and political repression to negate class struggle. In other words, the classical theory of imperialism believed that the development of capitalism in colonial societies would mirror its development in Europe, simultaneously bringing chaos, but also a chance at a socialist future through the creation of a working class.

By the postwar period, this view had declined in popularity, as many African and Afro-Caribbean writers began to note that a class society similar to Europe had failed to develop, and, as Fanon suggested, the rules of a developing

Most earlier writers on imperialism favored the view that imperialism had a contradictory effect on colonized nations’ development, simultaneously building up their productive forces, better integrating them into a world economy and providing education, while also bringing warfare, economic exploitation, and political repression to negate class struggle. In other words, the classical theory of imperialism believed that the development of capitalism in colonial societies would mirror its development in Europe, simultaneously bringing chaos, but also a chance at a socialist future through the creation of a working class.

By the postwar period, this view had declined in popularity, as many African and Afro-Caribbean writers began to note that a class society similar to Europe had failed to develop, and, as Fanon suggested, the rules of a developing

Many theories of imperialism have been used to explain a perceived tendency towards

Many theories of imperialism have been used to explain a perceived tendency towards

* John A. Hobson, Hobson, J.A.

*_Tom_Kemp.html" ;"title="910

'Finance Capital. A Study of the Latest Phase of Capitalist Development' Ed. Tom Bottomore Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1981

* Tom Kemp">Kemp, Tom

''An Introduction to the Study of Crisis''

Sep. 1929 issue of Journal of the Ohara Institute for Social Research, (vol. VI, no. 1) Translated by Michael Schauerte * Lenin V.I. [1916

Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

* Luxemburg, Rosa [1913

'The Accumulation of Capital: A Contribution to an Economic Explanation of Imperialism'

* Mommsen, Wolfgang J. ''Theories of Imperialism'' (German original 1977, Eng. trans. P.S. Falla 1980) University of Chicago Press, 1982 * Norfield, Tony 016''The City: London and the Global Power of Finance'', Verso, London * Pradella, Lucia

SAGE

* Joseph A. Schumpeter ''History of Economic Analysis'' Allen & Unwin 1954 * Winslow, E. 931 "Marxian, Liberal, and Sociological Theories of Imperialism". ''Journal of Political Economy'', 39(6), 713–758. Retrieved fro

JSTOR

* Gregory Zinoviev

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

into new areas, the unequal development of different countries, and economic system

An economic system, or economic order, is a system of production, resource allocation and distribution of goods and services within a society or a given geographic area. It includes the combination of the various institutions, agencies, entit ...

s that may lead to the dominance of some countries over others. These theories are considered distinct from other uses of the word imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

which refer to the general tendency for empires throughout history to seek power and territorial expansion. The theory of imperialism is often associated with Marxist economics, but many theories were developed by non-Marxists. Most theories of imperialism, with the notable exception of ultra-imperialism

Ultra-imperialism, or occasionally hyperimperialism and formerly super-imperialism, is a potential, comparatively peaceful phase of capitalism, meaning after or beyond imperialism. It was described mainly by Karl Kautsky. Post-imperialism is someti ...

, hold that imperialist exploitation leads to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regu ...

, colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

, and international inequality

International inequality refers to inequality between countries, as compared to global inequality, which is inequality between people across countries. International inequality research has primarily been concentrated on the rise of internati ...

.

Early theories

Marx

While most theories of imperialism are associated with

While most theories of imperialism are associated with Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

never used the term imperialism, nor wrote about any comparable theories. However many writers have suggested that ideas integral to later theories of imperialism were present in Marx's writings. For example, Frank Richards in 1979 noted that already in the ''Grundrisse

The ''Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie'' (''Foundations of a Critique of Political Economy'') is an unfinished manuscript by the German philosopher Karl Marx. The series of seven notebooks was rough-drafted by Marx, chiefly for ...

'' "Marx anticipated the Imperialist epoch." Lucia Pradella has argued that there was already an immanent theory of imperialism in Marx's unpublished studies of the world economy

The world economy or global economy is the economy of all humans of the world, referring to the global economic system, which includes all economic activities which are conducted both within and between nations, including production, consumptio ...

.

Marx's theory of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall

The tendency of the rate of profit to fall (TRPF) is a theory in the crisis theory of political economy, according to which the rate of profit—the ratio of the profit to the amount of invested capital—decreases over time. This hypothesis ...

was considered particularly important to later theorists of imperialism, as it seemed to explain why capitalist enterprises consistently require areas of higher profitability to expand into. Marx also noted the need for the capitalist mode of production as a whole to constantly expand into new areas, writing that "‘The need of a constantly expanding market chases the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere."

Marx also argued that certain colonial societies’ backwardness could only be explained through external intervention. In Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

Marx argued that English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

repression had forced Irish society to remain in a pre-capitalist mode. In India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

Marx was critical of the role of merchant capital, which he saw as preventing societal transformation where industrial capital might otherwise bring progressive change. Marx's writings on colonial societies are often considered by modern Marxists to contain contradictions or incorrect predictions, even if most agree he laid the foundation for later understandings of imperialism.

Hobson

J. A. Hobson

John Atkinson Hobson (6 July 1858 – 1 April 1940) was an English economist and social scientist. Hobson is best known for his writing on imperialism, which influenced Vladimir Lenin, and his theory of underconsumption.

His principal and ea ...

was an English liberal economist whose theory of imperialism was extremely influential among Marxist economists, particularly Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, and Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy. Hobson is best remembered for his '' Imperialism: A Study'', published 1902, which associated imperialism with the growth of monopoly capital and a subsequent underconsumption Underconsumption is a theory in economics that recessions and stagnation arise from an inadequate consumer demand, relative to the amount produced. In other words, there is a problem of overproduction and overinvestment during a demand crisis. The ...

crisis. Hobson argued that the growth of monopolies within capitalist countries tends to concentrate capital in fewer hands, leading to an increase in savings

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating Old English word , which is from an I ...

, and a corresponding decline in investment

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

. This excessive saving relative to investment leads to a chronic lack of demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item ...

, which can be relieved either through finding new territories to invest into, or finding new markets

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

with greater demand for goods. These two drives result in a need to safeguard the monopoly's foreign investments, or break up existing protections to better penetrate foreign markets, adding to the pressure to annex

Annex or Annexe refers to a building joined to or associated with a main building, providing additional space or accommodations.

It may also refer to:

Places

* The Annex, a neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada

* The Annex (New ...

foreign countries.

Hobson's opposition to imperialism was informed by his liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

, particularly the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

liberalism of Richard Cobden and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

. He alleged that imperialism was bad business due to high risk

In simple terms, risk is the possibility of something bad happening. Risk involves uncertainty about the effects/implications of an activity with respect to something that humans value (such as health, well-being, wealth, property or the environm ...

and high cost

In production, research, retail, and accounting, a cost is the value of money that has been used up to produce something or deliver a service, and hence is not available for use anymore. In business, the cost may be one of acquisition, in whic ...

s, as well as being bad for democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, and morally reprehensible. He claimed that imperialism only benefited a select few individuals, rather than the majority of British citizens, or even the majority of British capitalists. As an alternative, he proposed a proto-Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

solution of stimulating demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item ...

through the partial redistribution of income and wealth

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, confisc ...

within home markets.

Hobson's ideas were enormously influential, and most later theories of imperialism were in some way shaped by Hobson's arguments. Historians Peter Duignan and Lewis H. Gann

Lewis Henry Gann (1924–1997) was an American historian, political scientist and archivist. He was particularly known for his research in African history and specialized in the history of Central Africa in colonial era, writing a number of wor ...

argue that Hobson had an enormous influence in the early 20th century among people from all over the world:

By 1911, Hobson had largely reversed his position on imperialism, as he was convinced by arguments from his fellow radical liberals Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian-born political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of German-Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at H ...

, Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was a Norwegian-American economist and sociologist who, during his lifetime, emerged as a well-known critic of capitalism.

In his best-known book, ''The Theory of the Leisure Class'' ...

, and Norman Angell, who argued that imperialism itself was mutually beneficial for all societies involved, provided it was not perpetrated by a power with a fundamentally aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

, militaristic nature. This distinction between a benign "industrial imperialism" and a harmful "militarist imperialism" was similar to the earlier ideas of Spencer, and would prove foundational to later non-Marxist histories of imperialism.

Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

began expressing his theory of uneven and combined development in 1906, though the concept would only become prominent in his writing from 1927 onwards."Talk of uneven development becomes dominant in Trotsky's writings from 1927 onwards. From this date, whenever the law is mentioned, the claim consistently made for it is that 'the entire history of mankind is governed by the law of uneven development'." - Ian D. Thatcher

Ian D. Thatcher is a scholar of Russia.

Selected works

* ''Journal of Trotsky Studies'' (1993–)

* ''Leon Trotsky and World War One, August 1914–February 1917'' (2000)

* ''Trotsky'' (2003)

*

*

*

*

*

*

References

External li ...

, "Uneven and combined development", ''Revolutionary Russia'', Vol. 4 No. 2, 1991, p. 237. Trotsky observed that different countries developed and advanced to a large extent independently from each other, in ways which were quantitatively unequal (e.g. the local rate and scope of economic growth

Economic growth can be defined as the increase or improvement in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy in a financial year. Statisticians conventionally measure such growth as the percent rate o ...

and population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. Actual global human population growth amounts to around 83 million annually, or 1.1% per year. The global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to ...

) and qualitatively different (e.g. nationally specific cultures and geographical features). In other words, countries had their own specific national history with national peculiarities. At the same time, all the different countries did not exist in complete isolation from each other; they were also interdependent parts of a world society, a larger totality, in which they all co-existed together, in which they shared many characteristics, and in which they influenced each other through processes of cultural diffusion

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technolo ...

, trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

, political relations and various "spill-over effects" from one country to another.Leon Trotsky, "Peculiarities of Russia's development", chapter 1 in ''History of the Russian Revolution'', Vol. /ref> In ''The History of the Russian Revolution'', published in 1932, Trotsky tied his theory of development to a theory of imperialism. In Trotsky's theory of imperialism, the domination of one country by another does not mean that the dominated country is prevented from development altogether, but rather that it develops mainly according to the requirements of the dominating country. Trotsky's later writings show that uneven and combined development is less of a theory of

development economics

Development economics is a branch of economics which deals with economic aspects of the development process in low- and middle- income countries. Its focus is not only on methods of promoting economic development, economic growth and structural ...

, and more of a general dialectical

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing t ...

category that governs personal, historical, and even biological development

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and differentiation of stem ce ...

. The theory was nonetheless influential in imperialism studies, as it may have influenced passages in Rudolf Hilferding

Rudolf Hilferding (10 August 1877 – 11 February 1941) was an Austrian-born Marxist economist, socialist theorist,International Institute of Social History, ''Rodolf Hilferding Papers''. http://www.iisg.nl/archives/en/files/h/10751012.php poli ...

's ''Finance Capital'',Marcel van der Linden, "The 'Law' of Uneven and Combined Development: Some Underdeveloped Thoughts". ''Historical Materialism'', Volume 15, Number 1, 2007, pp. 145-165. as well as later theories of economic geography

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography which studies economic activity and factors affecting them. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics.

There are four branches of economic geography.

There is,

primary sect ...

.

Hilferding

Rudolf Hilferding's ''Finance Capital'', published in 1910, is considered the first of the "classical" Marxist theories of imperialism which would be codified and popularized by

Rudolf Hilferding's ''Finance Capital'', published in 1910, is considered the first of the "classical" Marxist theories of imperialism which would be codified and popularized by Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

and Lenin. Hilferding began his analysis of imperialism with a very thorough treatment of monetary economics

Monetary economics is the branch of economics that studies the different competing theories of money: it provides a framework for analyzing money and considers its functions (such as medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account), and ...

and an analysis of the rise of joint stock companies

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders are ...

. The rise of joint stock companies, as well as banking monopolies, led to unprecedented concentrations of capital. As monopolies took direct control of buying and selling, opportunities for investment in commerce declined. This had the effect of essentially forcing banking monopolies to invest directly in production, as Hilferding writes:

Hilferding's finance capital is best understood as a fraction of capital in which the functions of

Hilferding's finance capital is best understood as a fraction of capital in which the functions of financial capital

Financial capital (also simply known as capital or equity in finance, accounting and economics) is any economic resource measured in terms of money used by entrepreneurs and businesses to buy what they need to make their products or to provi ...

and industrial capital are united. The era of finance capital would be one marked by large companies which are able to raise money from a wide range of sources. These finance-capital-heavy companies would then seek to expand into a large area of operations in order to make the most efficient use of natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

and, having monopolised that area, erect tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

on exported goods in order to exploit their monopoly position. This process is summarized by Hilferding as follows:

To Hilferding, monopolies exploited all consumers within their protected areas, not just colonial subjects, however he did believe that " olent methods are of the essence of colonial policy, without which it would lose its capitalist rationale." Thus like Hobson, Hilferding believed that imperialism benefits only a minority of the bourgeoisie.

While acknowledged by Lenin as an important contributor to the theory of Imperialism, Hilferding's position as finance minister in the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

from 1923 discredited him in the eyes of many socialists. Hilferding's influence on later theories was thus largely transmitted through Lenin's work, as his own work was rarely acknowledged or translated, and went out of print several times.

Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialism, revolutionary socialist, Marxism, Marxist philosopher and anti-war movement, anti-war activist. Succ ...

followed Marx's interpretation of the expansion of the capitalist mode of production very closely. In '' The Accumulation of Capital'', published in 1913, Luxemburg drew on a close reading of Marx to make several arguments about Imperialism. First, she argued that Marx had made a logical error in his analysis of extended reproduction, which would make it impossible for goods to be sold at prices high enough to cover the costs of reinvestment, meaning that buyers external to the capitalist system would be required for capitalist production to remain profitable. Second, she argued that capitalism is surrounded by pre-capitalist economies, and that competition forces capitalist firms to expand into these economies and ultimately destroy them. These competing drives to exploit and destroy pre-capitalist societies led Luxemburg to the conclusion that capitalism would end once it ran out of pre-capitalist societies to exploit, leading her to campaign against war and colonialism.

Luxemburg's underconsumptionist argument was heavily criticised by many Marxist and non-Marxist economists as too crude, although it gained a noted defender in György Lukács

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; hu, szegedi Lukács György Bernát; german: Georg Bernard Baron Lukács von Szegedin; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, critic, and aesth ...

. While Luxemburg's analysis of imperialism did not prove to be as influential as other theories, she has been praised for urging early Marxists to focus on the Global South

The concept of Global North and Global South (or North–South divide in a global context) is used to describe a grouping of countries along socio-economic and political characteristics. The Global South is a term often used to identify region ...

rather than solely on advanced, industrialized countries.

Kautsky

Prior to the

Prior to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Hobson, as well as Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag fro ...

had theorized that imperialist states could, in the future, potentially transform into interstate cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collude with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. Cartels are usually associations in the same sphere of business, and thus an alliance of rivals. Mos ...

s which could more efficiently exploit the remainder of the world without causing warfare in Europe. In 1914 Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels ...

expressed a similar idea, coining the term ultra-imperialism, or a stage of peaceful cooperation between imperialist powers, where countries would forego arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

s and limit competition. This implied that warfare is not essential to capitalism, and that socialists should agitate towards a peaceful capitalism, rather than an end to imperialism.Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels ...

, Ultra-imperialism

'. Kautsky's idea is often best remembered for Lenin's frequent criticism of the concept. In an introduction to Bukharin's ''Imperialism and World Economy'' for example, Lenin contended that "in the abstract one can think of such a phase. In practice, however, he who denies the sharp tasks of to-day in the name of dreams about soft tasks of the future becomes an opportunist". Despite being sharply criticized in its own day, ultra-imperialism has been revived to describe instances of inter-imperialist cooperation in later years, such as cooperation among

capitalist state

The capitalist state is the state, its functions and the form of organization it takes within capitalist socioeconomic systems.Jessop, Bob (January 1977). "Recent Theories of the Capitalist State". ''Soviet Studies''. 1: 4. pp. 353–373. This ...

s in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

.Lenin, Kautsky and "ultra-imperialism"

',

World Socialist Web Site

The World Socialist Web Site (WSWS) is the website of the International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI). It describes itself as an "online newspaper of the international Trotskyist movement". The WSWS publishes articles and analys ...

. Commentators have also pointed out similarities between Kautsky's theory and Michael Hardt

Michael Hardt (born 1960) is an American political philosopher and literary theorist. Hardt is best known for his book ''Empire'', which was co-written with Antonio Negri.

Hardt and Negri suggest that several forces which they see as domin ...

and Antonio Negri

Antonio "Toni" Negri (born 1 August 1933) is an Italian Spinozistic-Marxist sociologist and political philosopher, best known for his co-authorship of ''Empire'' and secondarily for his work on Spinoza.

Born in Padua, he became a political p ...

's theory of empire, however the authors dispute this.

Bukharin

anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

light. Bukharin's main difference with Hilferding was that rather than a single process that leads to imperialism (the increasing concentration of finance capital), Bukharin saw two competing processes that would create friction and warfare. These were the "internationalization

In economics, internationalization or internationalisation is the process of increasing involvement of enterprises in international markets, although there is no agreed definition of internationalization. Internationalization is a crucial strateg ...

" of capital (the growing interdependence of the world economy), and the "nationalization" of capital (the division of capital into national power blocs). The result of these tendencies would be large national blocs of capital competing within a world economy, or in Bukharin's words:

Competition and other independent market forces would, in this system, be relatively restrained at the national level, but much more disruptive at the world level. Monopoly was thus not an end to competition, but rather each successive intensification of Monopoly capital into larger blocs would entail a much more intensive form of competition, at ever larger scales.

Bukharin's theory of imperialism is also notable for reintroducing the theory of a labor aristocracy in order to explain the perceived failure of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

. Bukharin argued that increased superprofit

Superprofit, surplus profit or extra surplus-value (german: extra-Mehrwert) is a concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy subsequently elaborated by Vladimir Lenin and other Marxist thinkers.

Origin of the concept in Karl Marx's '' ...

s from the colonies constituted the basis for higher wage

A wage is payment made by an employer to an employee for work done in a specific period of time. Some examples of wage payments include compensatory payments such as ''minimum wage'', '' prevailing wage'', and ''yearly bonuses,'' and remune ...

s in advanced countries, causing some workers to identify with the interests of their state rather than their class. The same idea would be taken up by Lenin.

Lenin

Despite being a relatively small text which sought only to summarize the earlier ideas of Hobson, Hilferdung and Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet '' Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'' is easily the most influential, widely read text on the subject of imperialism.

Lenin's argument differs from previous writers in that rather than viewing imperialism as a distinct

Despite being a relatively small text which sought only to summarize the earlier ideas of Hobson, Hilferdung and Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet '' Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'' is easily the most influential, widely read text on the subject of imperialism.

Lenin's argument differs from previous writers in that rather than viewing imperialism as a distinct policy

Policy is a deliberate system of guidelines to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes. A policy is a statement of intent and is implemented as a procedure or protocol. Policies are generally adopted by a governance body within an orga ...

of certain countries and states (as Bukharin had done, for example), he saw imperialism as a new historical stage in capitalist development, and all imperialist policies were simply characteristic of this stage. The progression into this stage would be complete when:

*"(1) the concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life"

*"(2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this ‘finance capital’ of a financial oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

"

*"(3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance"

*"(4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist combines which share the world among themselves"

*"(5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed."

The importance of Lenin's pamphlet has been debated by later writers due to its status within the communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

movement. Some, such as Anthony Brewer, have argued that Imperialism is a "popular outline" which has been unfairly treated as a "sacred text", and that many arguments (such as Lenin's contention that industry requires capital export to survive) are not as well developed as in his contemporaries’ work. Others have argued that Lenin's prefiguration of a core-periphery divide and use of the term "world system" were crucial to the later development of dependency theory

Dependency theory is the notion that resources flow from a " periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a " core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. A central contention of dependency theory is that poor ...

and world-systems theory

World-systems theory (also known as world-systems analysis or the world-systems perspective)Immanuel Wallerstein, (2004), "World-systems Analysis." In ''World System History'', ed. George Modelski, in ''Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems'' (E ...

.

Postwar theories

Baran and Sweezy

Between the publication of Lenin's ''Imperialism'' in 1916 and Paul Sweezy's ''The Theory of Capitalist Development'' in 1942 and Paul A. Baran's ''Political Economy of Growth'' in 1957, there was a notable lack of development in the Marxist theory of imperialism, best explained by the elevation of Lenin's work to the status of Marxist orthodoxy. Like Hobson, Baran and Sweezy employed an underconsumptionist line of reasoning to argue that infinite growth of the capitalist system is impossible. They argued that as capitalism develops, wages tend to decline, and with them, the total level of consumption. The ability for consumption to absorb the total productive output of society is therefore limited, and this output must then be reinvested elsewhere. Since Sweezy implies that it would be impossible to continuously reinvest in productive machinery (which would only increase the output of consumer goods, adding to the initial problem), there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the need to increase investments to absorb surplus output, and the need to reduce overall output to match consumer demand. This problem can, however, be delayed through investments in unproductive aspects of society (such as the military), or through capital export.

Between the publication of Lenin's ''Imperialism'' in 1916 and Paul Sweezy's ''The Theory of Capitalist Development'' in 1942 and Paul A. Baran's ''Political Economy of Growth'' in 1957, there was a notable lack of development in the Marxist theory of imperialism, best explained by the elevation of Lenin's work to the status of Marxist orthodoxy. Like Hobson, Baran and Sweezy employed an underconsumptionist line of reasoning to argue that infinite growth of the capitalist system is impossible. They argued that as capitalism develops, wages tend to decline, and with them, the total level of consumption. The ability for consumption to absorb the total productive output of society is therefore limited, and this output must then be reinvested elsewhere. Since Sweezy implies that it would be impossible to continuously reinvest in productive machinery (which would only increase the output of consumer goods, adding to the initial problem), there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the need to increase investments to absorb surplus output, and the need to reduce overall output to match consumer demand. This problem can, however, be delayed through investments in unproductive aspects of society (such as the military), or through capital export.

In addition to this underconsumptionist argument, Baran and Sweezy argued that there are two motives for investment in industry: increasing productive output, and introducing new productive techniques. While in conventional competitive capitalism, any firm which does not introduce new productive techniques will usually fall behind and become unprofitable, in monopoly capitalism, there is actually no incentive to introduce new productive techniques, as there are no rivals to gain a competitive advantage over, and thus no reason to render one's own machinery obsolete. This is a key difference with the earlier "classical" theories of imperialism, especially Bukharin, as here monopoly does not represent an intensification of competition but rather its total suppression. Baran and Sweezy also rejected the earlier claim that all national industries would form a single "national cartel," instead noting that there tended to be a number of monopoly companies within a country: just enough to maintain a "balance of power."

The connection to imperialist violence then, is that most western nations have sought to solve their underconsumption crises by investing heavily into military armaments, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In addition to this, capital exports into the less concretely divided areas of the world have increased, and monopoly companies seek protection from their parent states in order to secure these foreign investments. To Baran and Sweezy, these two factors explain imperialist warfare and the dominance of developed countries.

Conversely, they explain the underdevelopment of poor nations through trade flows. Trade flows serve to provide cheap primary goods to the advanced countries, while local manufacturing in underdeveloped countries is discouraged through competition with goods from the advanced countries. Baran and Sweezy were the first economists to treat the development of capitalism in the advanced countries as different from its development in the underdeveloped countries, an outlook influenced by the philosophy of

In addition to this underconsumptionist argument, Baran and Sweezy argued that there are two motives for investment in industry: increasing productive output, and introducing new productive techniques. While in conventional competitive capitalism, any firm which does not introduce new productive techniques will usually fall behind and become unprofitable, in monopoly capitalism, there is actually no incentive to introduce new productive techniques, as there are no rivals to gain a competitive advantage over, and thus no reason to render one's own machinery obsolete. This is a key difference with the earlier "classical" theories of imperialism, especially Bukharin, as here monopoly does not represent an intensification of competition but rather its total suppression. Baran and Sweezy also rejected the earlier claim that all national industries would form a single "national cartel," instead noting that there tended to be a number of monopoly companies within a country: just enough to maintain a "balance of power."

The connection to imperialist violence then, is that most western nations have sought to solve their underconsumption crises by investing heavily into military armaments, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In addition to this, capital exports into the less concretely divided areas of the world have increased, and monopoly companies seek protection from their parent states in order to secure these foreign investments. To Baran and Sweezy, these two factors explain imperialist warfare and the dominance of developed countries.

Conversely, they explain the underdevelopment of poor nations through trade flows. Trade flows serve to provide cheap primary goods to the advanced countries, while local manufacturing in underdeveloped countries is discouraged through competition with goods from the advanced countries. Baran and Sweezy were the first economists to treat the development of capitalism in the advanced countries as different from its development in the underdeveloped countries, an outlook influenced by the philosophy of Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961), also known as Ibrahim Frantz Fanon, was a French West Indian psychiatrist, and political philosopher from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have b ...

and Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse (; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German-American philosopher, social critic, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at the Humboldt University ...

.

In doing so Baran and Sweezy were the first theorists to popularize the idea that imperialism is not a force which is both progressive and destructive, but rather that it is destructive as well as a barrier to development in many countries. This conclusion proved influential, and lead to the "underdevelopment school" of economics, however their reliance on underconsumptionist logic has been criticised as empirically flawed. Their theory also attracted renewed interest in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–2008

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of ...

.

Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

, former president of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

(1960–66), coined the term Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, ...

, which appeared in the 1963 preamble of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

Charter, and was the title of his 1965 book ''Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism''. Nkrumah's theory was largely based in Lenin's ''Imperialism'', and followed similar themes to the classical Marxist theories of imperialism, describing imperialism as the result of a need to export crises to areas outside Europe. However unlike the classical Marxist theories, Nkrumah saw imperialism as holding back the development of the colonized world, writing:

Nkrumah's combination of elements from classical Marxist theories of imperialism with the conclusion that imperialism systematically underdevelops poor nations would, like the similar writings of Ché Guevara, prove influential among leaders of the non-aligned movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

and various national-liberation groups.

Cabral

Amílcar Cabral, leader of the nationalist movement inGuinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

and the Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, developed an original theory of imperialism to better explain the relationship between Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

and its colonies. Cabral's theory of history held that there are three distinct phases of human development. In the first, social structures are horizontal, lacking private property and classes, and with a low level of productive forces. In the second, social structures are vertical, with a class society, private property, and a high level of productive forces. In the final stage, social structures are once again horizontal, lacking private property and classes, but with an extremely high level of productive forces. Cabral differed from historical materialism

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

in that he did not believe that the progression through such historical stages was the result of class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

, rather that a mode of production has its own independent character which can effect change, and only in the second phase of development can class struggle change societies. Cabral's point was that classless indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

have a history of their own, and are capable of social transformation without the development of classes. Imperialism, then, represented any barrier to indigenous social transformation, with Cabral noting that colonial society had failed to develop a mature set of class dynamics. This theory of imperialism was not influential outside of Cabral's own movement.

Frank

Andre Gunder Frank

Andre Gunder Frank (February 24, 1929 – April 25, 2005) was a German-American sociologist and economic historian who promoted dependency theory after 1970 and world-systems theory after 1984. He employed some Marxian concepts on politi ...

was influential in the development of dependency theory, which would dominate discussions of radical economics in the 1960s and 70s. Like Baran and Sweezy, and the African theorists of imperialism, Frank believed that capitalism produces underdevelopment in many areas of the world. He saw the world as divided into a metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural center for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big c ...

and satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioiso ...

, or a set of dominant and dependent countries with a widening gap in development outcomes between them. To Frank, any part of the world touched by capitalist exchange was described as "capitalist," even areas of high self-sufficiency or peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

agriculture, and much of his work was devoted to demonstrating the degree to which capitalism had penetrated into traditional societies.

Frank saw capitalism as a "chain" of satellite-to-metropolis relations in which metropolitan industry siphons away a portion of the surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to the owner of that product to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cos ...

from smaller regional centers, which in-turn siphon value from smaller centers and individuals. Each metropolis has an effective monopoly position over the output of its satellites. In Frank's earlier writings he believed this system of relations extended back to the 16th century

The 16th century begins with the Julian year 1501 ( MDI) and ends with either the Julian or the Gregorian year 1600 ( MDC) (depending on the reckoning used; the Gregorian calendar introduced a lapse of 10 days in October 1582).

The 16th centur ...

, while in his later work (after his adoption of world-systems theory

World-systems theory (also known as world-systems analysis or the world-systems perspective)Immanuel Wallerstein, (2004), "World-systems Analysis." In ''World System History'', ed. George Modelski, in ''Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems'' (E ...

) he believed it extended as far back as the 4th millennium BC

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. ...

.

This chain of satellite-metropolis relations is cited as the reason for "the development of underdevelopment" in the satellite, a quantitative retardation in output, productivity and employment. Frank cited evidence that the outflows of profit from Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

greatly exceed the investments flowing in the other direction from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. In addition to this transfer of surplus, Frank noted that satellite economies become "distorted" over time, developing a low-waged, primary goods-producing industrial sector with few available jobs, leaving much of the country reliant on pre-industrial production. He coined the term lumpenbourgeoisie