Theology of John Calvin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The theology of John Calvin has been influential in both the development of the system of belief now known as

The theology of John Calvin has been influential in both the development of the system of belief now known as

The first statement in the ''Institutes'' acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as ''autopiston'' or self-authenticating. He defends the

The first statement in the ''Institutes'' acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as ''autopiston'' or self-authenticating. He defends the

Calvin's Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A blot upon his labors as a public instructor?

'' WTJ'' 73 (2011):217. For Calvin,

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli, a Protestant minister in Lausanne accused Calvin, as well as Viret and Farel, of Arianism in 1536. Calvin defended his beliefs on the Trinity in ''Confessio de Trinitate propter calumnias P. Caroli''. In 1551 Jérôme-Hermès Bolsec, a physician in Geneva, attacked Calvin's doctrine of predestination and accused him of making God the author of sin. Bolsec was banished from the city, and after Calvin's death, he wrote a biography which severely maligned Calvin's character. In the following year, Joachim Westphal, a Gnesio-Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, condemned Calvin and Zwingli as heretics in denying the eucharistic doctrine of the union of Christ's body with the elements. Calvin's ''Defensio sanae et orthodoxae doctrinae de sacramentis'' (A Defence of the Sober and Orthodox Doctrine of the Sacrament) was his response in 1555. In 1556

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli, a Protestant minister in Lausanne accused Calvin, as well as Viret and Farel, of Arianism in 1536. Calvin defended his beliefs on the Trinity in ''Confessio de Trinitate propter calumnias P. Caroli''. In 1551 Jérôme-Hermès Bolsec, a physician in Geneva, attacked Calvin's doctrine of predestination and accused him of making God the author of sin. Bolsec was banished from the city, and after Calvin's death, he wrote a biography which severely maligned Calvin's character. In the following year, Joachim Westphal, a Gnesio-Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, condemned Calvin and Zwingli as heretics in denying the eucharistic doctrine of the union of Christ's body with the elements. Calvin's ''Defensio sanae et orthodoxae doctrinae de sacramentis'' (A Defence of the Sober and Orthodox Doctrine of the Sacrament) was his response in 1555. In 1556

The theology of John Calvin has been influential in both the development of the system of belief now known as

The theology of John Calvin has been influential in both the development of the system of belief now known as Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and in Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

thought more generally.

Publications

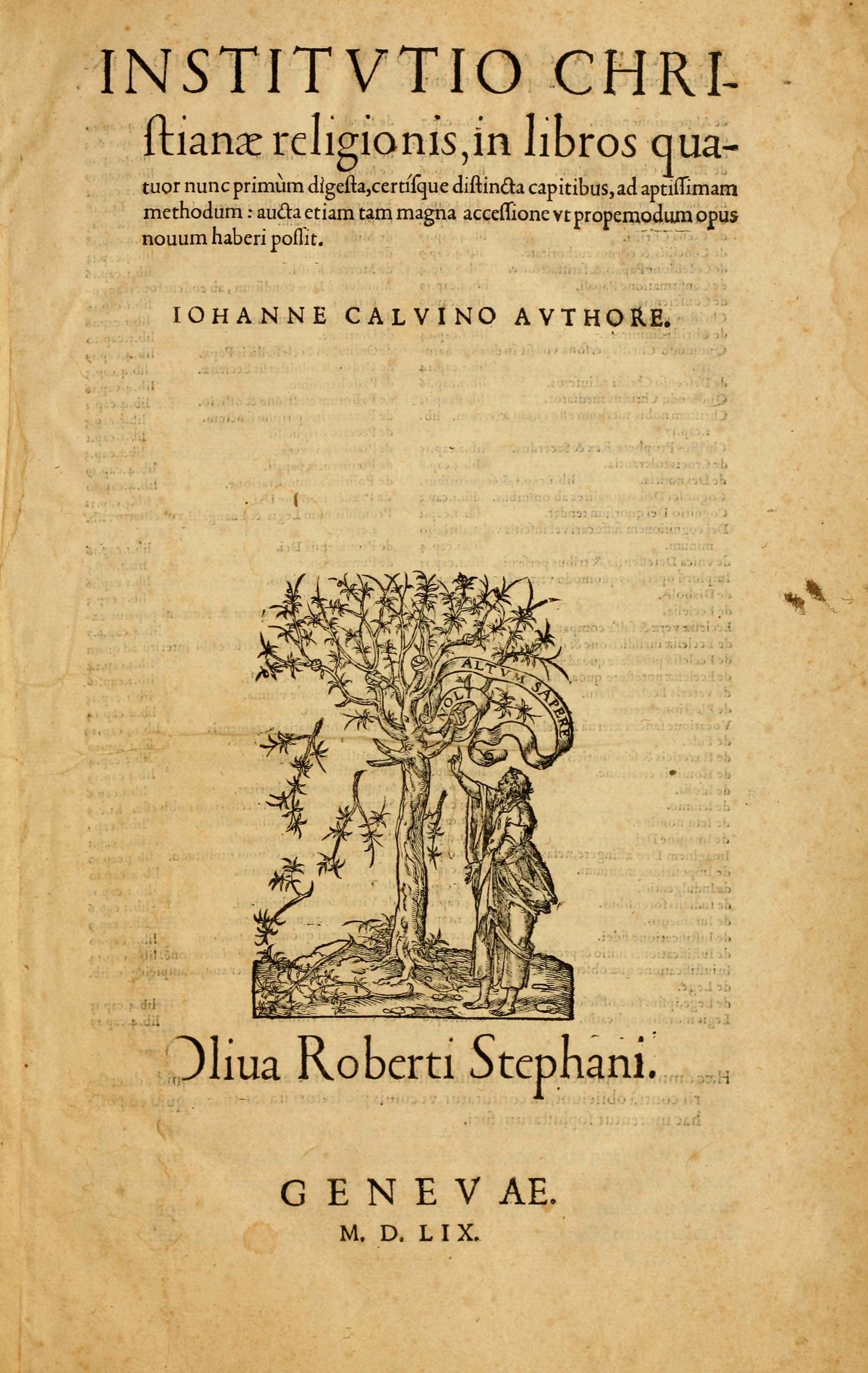

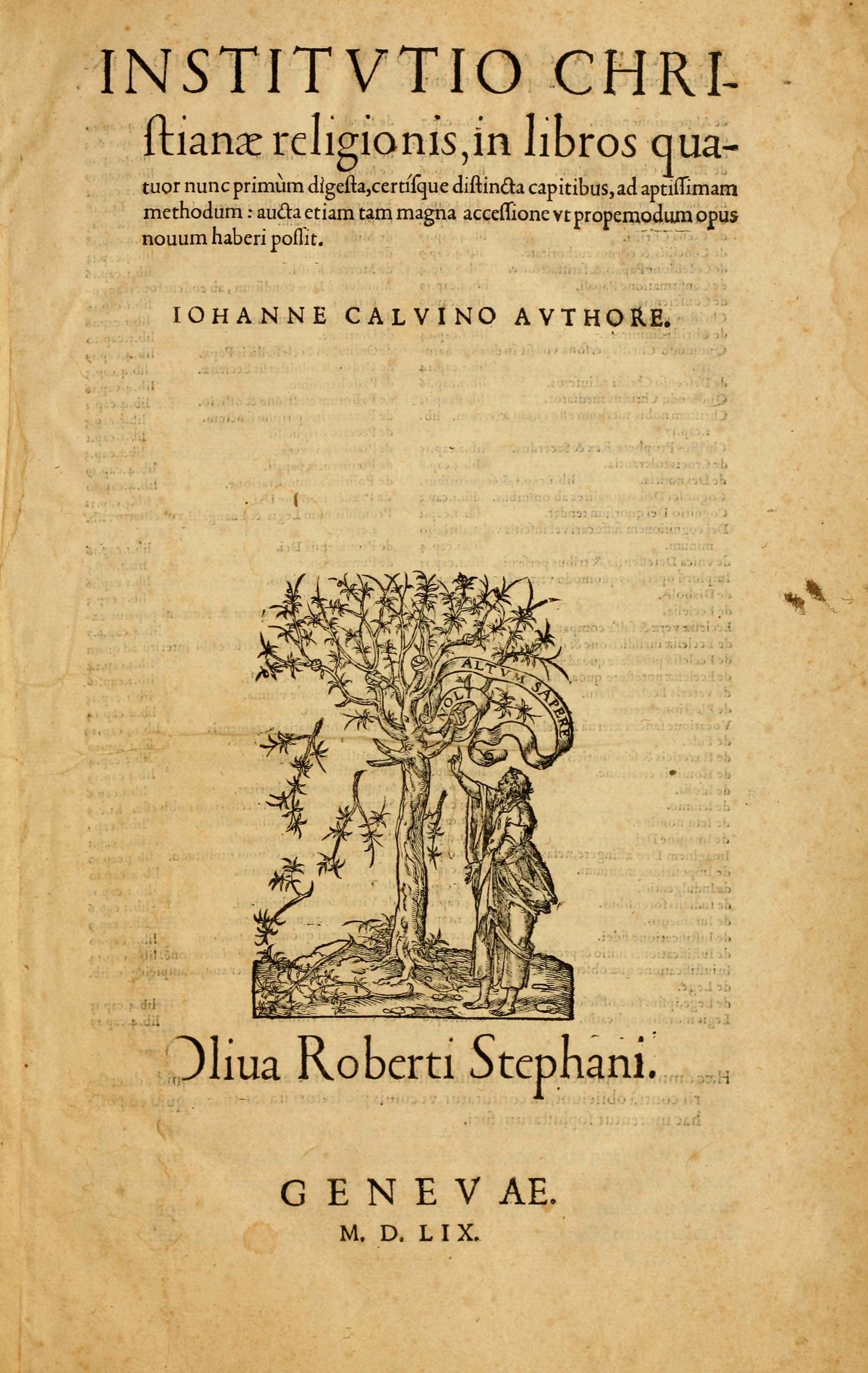

John Calvin developed his theology in his biblical commentaries as well as his sermons and treatises, but the most concise expression of his views is found in his magnum opus, the ''Institutes of the Christian Religion

''Institutes of the Christian Religion'' ( la, Institutio Christianae Religionis) is John Calvin's seminal work of systematic theology. Regarded as one of the most influential works of Protestant theology, it was published in Latin in 1536 (at th ...

''. He intended that the book be used as a summary of his views on Christian theology and that it be read in conjunction with his commentaries. The various editions of that work span nearly his entire career as a reformer, and the successive revisions of the book show that his theology changed very little from his youth to his death. The first edition from 1536 consisted of only six chapters. The second edition, published in 1539, was three times as long because he added chapters on subjects that appear in Melanchthon's '' Loci Communes''. In 1543, he again added new material and expanded a chapter on the Apostles' Creed

The Apostles' Creed (Latin: ''Symbolum Apostolorum'' or ''Symbolum Apostolicum''), sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles, is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

The creed most likely originated in 5th-century ...

. The final edition of the ''Institutes'' appeared in 1559. By then, the work consisted of four books of eighty chapters, and each book was named after statements from the creed: Book 1 on God the Creator, Book 2 on the Redeemer in Christ, Book 3 on receiving the Grace of Christ through the Holy Spirit, and Book 4 on the Society of Christ or the Church.

Themes

Scripture

The first statement in the ''Institutes'' acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as ''autopiston'' or self-authenticating. He defends the

The first statement in the ''Institutes'' acknowledges its central theme. It states that the sum of human wisdom consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. Calvin argues that the knowledge of God is not inherent in humanity nor can it be discovered by observing this world. The only way to obtain it is to study scripture. Calvin writes, "For anyone to arrive at God the Creator he needs Scripture as his Guide and Teacher." He does not try to prove the authority of scripture but rather describes it as ''autopiston'' or self-authenticating. He defends the trinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

view of God and, in a strong polemical stand against the Catholic Church, argues that images

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensiona ...

of God lead to idolatry.

Calvin viewed Scripture as being both ''majestic'' and ''simple''. According to Ford Lewis Battles, Calvin had discovered that "sublimity of style and sublimity of thought were not coterminous."

Providence

At the end of the first book of the ''Institutes'', he offers his views on providence, writing, "By his Power God cherishes and guards the World which he made and by his Providence rules its individual Parts. Humans are unable to fully comprehend why God performs any particular action, but whatever good or evil people may practise, their efforts always result in the execution of God's will and judgments."Sin

The second book of the ''Institutes'' includes several essays on the original sin and thefall of man

The fall of man, the fall of Adam, or simply the Fall, is a term used in Christianity to describe the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience.

*

*

*

* The doctrine of the ...

, which directly refer to Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

, who developed these doctrines. He often cited the Church Fathers in order to defend the reformed cause against the charge that the reformers were creating new theology. In Calvin's view, sin began with the fall of Adam and propagated to all of humanity. The domination of sin is complete to the point that people are driven to evil. Thus fallen humanity is in need of the redemption that can be found in Christ. But before Calvin expounded on this doctrine, he described the special situation of the Jews who lived during the time of the Old Testament. God made a covenant with Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

, promising the coming of Christ. Hence, the Old Covenant

The Mosaic covenant (named after Moses), also known as the Sinaitic covenant (after the biblical Mount Sinai), refers to a covenant between God and the Israelites, including their proselytes, not limited to the ten commandments, nor the eve ...

was not in opposition to Christ, but was rather a continuation of God's promise. Calvin then describes the New Covenant

The New Covenant (Hebrew '; Greek ''diatheke kaine'') is a biblical interpretation which was originally derived from a phrase which is contained in the Book of Jeremiah ( Jeremiah 31:31-34), in the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament of the ...

using the passage from the Apostles' Creed

The Apostles' Creed (Latin: ''Symbolum Apostolorum'' or ''Symbolum Apostolicum''), sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles, is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

The creed most likely originated in 5th-century ...

that describes Christ's suffering under Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of ...

and his return to judge the living and the dead. For Calvin, the whole course of Christ's obedience to the Father removed the discord between humanity and God.

Atonement

R. T. Kendall has argued that Calvin's view of theatonement

Atonement (also atoning, to atone) is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some other ...

differs from that of later Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

s, especially the Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

. Kendall interpreted Calvin as believing that Christ died for all people, but intercedes only for the elect.

Kendall's thesis is now a minority view as a result of work by scholars such as Paul Helm

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

, who argues that "both Calvin and the Puritans taught that Christ died for the elect and intercedes for the elect", Richard Muller, Mark Dever, and others.

Union with Christ

In the third book of the ''Institutes'', Calvin describes how the spiritual union of Christ and humanity is achieved. He first defines faith as the firm and certain knowledge of God in Christ. The immediate effects of faith are repentance and the remission of sin. This is followed by spiritual regeneration, which returns the believer to the state of holiness before Adam's transgression. However, complete perfection is unattainable in this life, and the believer should expect a continual struggle against sin. Several chapters are then devoted to the subject of justification by faith alone. He defined justification as "the acceptance by which God regards us as righteous whom he has received into grace." In this definition, it is clear that it is God who initiates and carries through the action and that people play no role; God is completely sovereign in salvation. According toAlister McGrath

Alister Edgar McGrath (; born 1953) is a Northern Irish theologian, Anglican priest, intellectual historian, scientist, Christian apologist, and public intellectual. He currently holds the Andreas Idreos Professorship in Science and Religion i ...

, Calvin provided a solution to the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

problem of how justification relates to sanctification. Calvin suggested that both came out of union with Christ. McGrath notes that while Martin Bucer suggested that justification causes (moral) regeneration, Calvin argued that "both justification and regeneration are the results of the believer's union with Christ through faith."

Predestination

Near the end of the ''Institutes'', Calvin describes and defends the doctrine ofpredestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

, a doctrine advanced by Augustine in opposition to the teachings of Pelagius

Pelagius (; c. 354–418) was a British theologian known for promoting a system of doctrines (termed Pelagianism by his opponents) which emphasized human choice in salvation and denied original sin. Pelagius and his followers abhorred the moral ...

. Fellow theologians who followed the Augustinian tradition on this point included Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

and Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, though Calvin's formulation of the doctrine went further than the tradition that went before him. The principle, in Calvin's words, is that "All are not created on equal terms, but some are preordained to eternal life, others to eternal damnation; and, accordingly, as each has been created for one or other of these ends, we say that he has been predestinated to life or to death."

The doctrine of predestination "does not stand at the beginning of the dogmatic system as it does in Zwingli or Beza", but, according to Fahlbusch, it "does tend to burst through the soteriological-Christological framework." In contrast to some other Protestant Reformers, Calvin taught double predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby ...

. Chapter 21 of Book III of the ''Institutes'' is called "Of the eternal election, by which God has predestinated some to salvation, and others to destruction".

Ecclesiology and sacraments

The final book of the ''Institutes'' describes what he considers to be the true Church and its ministry, authority, and sacraments. He denied the papal claim to primacy and the accusation that the reformers were schismatic. For Calvin, the Church was defined as the body of believers who placed Christ at its head. By definition, there was only one "catholic" or "universal" Church. Hence, he argued that the reformers "had to leave them in order that we might come to Christ." The ministers of the Church are described from a passage fromEphesians

The Epistle to the Ephesians is the tenth book of the New Testament. Its authorship has traditionally been attributed to Paul the Apostle but starting in 1792, this has been challenged as Deutero-Pauline, that is, pseudepigrapha written in Pau ...

, and they consisted of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and doctors. Calvin regarded the first three offices as temporary, limited in their existence to the time of the New Testament. The latter two offices were established in the church in Geneva. Although Calvin respected the work of the ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

s, he considered them to be subject to God's Word found in scripture. He also believed that the civil and church authorities were separate and should not interfere with each other.

Calvin defined a sacrament as an earthly sign associated with a promise from God. He accepted only two sacraments as valid under the new covenant: baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

and the Lord's Supper (in opposition to the Catholic acceptance of seven sacraments). He completely rejected the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις '' metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of ...

and the treatment of the Supper as a sacrifice. He also could not accept the Lutheran doctrine of sacramental union

Sacramental union (Latin: ''unio sacramentalis''; Martin Luther's German: ''Sacramentliche Einigkeit'';''Weimar Ausgabe'' 26, 442.23; ''Luther's Works'' 37, 299-300. German: ''sakramentalische Vereinigung'') is the Lutheran theological doctrine o ...

in which Christ was "in, with and under" the elements. His own view was close to Zwingli's symbolic view, but it was not identical. Rather than holding a purely symbolic view, Calvin noted that with the participation of the Holy Spirit, faith was nourished and strengthened by the sacrament. In his words, the eucharistic rite was "a secret too sublime for my mind to understand or words to express. I experience it rather than understand it." Keith Mathison

Keith A. Mathison (born 1967) is an American Reformed theologian.

Mathison grew up near Houston, Texas. He began graduate studies at Dallas Theological Seminary before transferring to Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando. After completing his ...

coined the word "suprasubstantiation" (in distinction to transubstantiation or consubstantiation) to describe Calvin’s doctrine of the Lord's Supper.

In common with other Protestant Reformers, Calvin believed that there were only two sacraments, baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

and the Lord's Supper

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. Calvin also conceded that ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

could also be called a sacrament, but suggested that it was a "special rite for a certain function."

Calvin believed in infant baptism

Infant baptism is the practice of baptising infants or young children. Infant baptism is also called christening by some faith traditions.

Most Christians belong to denominations that practice infant baptism. Branches of Christianity that ...

, and devoted a chapter in his ''Institutes'' to the subject.

Calvin believed in a real spiritual presence of Christ at the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

.Ralph Cunnington,Calvin's Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A blot upon his labors as a public instructor?

'' WTJ'' 73 (2011):217. For Calvin,

union with Christ

In its widest sense, the phrase union with Christ refers to the relationship between the believer and Jesus Christ. In this sense, John Murray says, union with Christ is "the central truth of the whole doctrine of salvation." The expression "in Ch ...

was at the heart of the Lord's Supper.

According to Brian Gerrish, there are three different interpretations of the Lord's Supper within non-Lutheran Protestant theology:

#''Symbolic memorialism'', found in Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

, which sees the elements merely as a sign pointing to a past event;

#''Symbolic parallelism'', typified by Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss R ...

, which sees the sign as pointing to “a happening that occurs simultaneously in the present” ''alongside'' the sign itself; and

#''Symbolic instrumentalism'', Calvin's view, which holds that the Eucharist is “a present happening that is actually brought about through the signs.”

Calvin's sacramental theology was criticized by later Reformed writers. Robert L. Dabney, for example, called it “not only incomprehensible but impossible.”

Other beliefs

Mary

Calvin had a positive view ofMary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, but rejected the Roman Catholic veneration of her.

Controversies

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli, a Protestant minister in Lausanne accused Calvin, as well as Viret and Farel, of Arianism in 1536. Calvin defended his beliefs on the Trinity in ''Confessio de Trinitate propter calumnias P. Caroli''. In 1551 Jérôme-Hermès Bolsec, a physician in Geneva, attacked Calvin's doctrine of predestination and accused him of making God the author of sin. Bolsec was banished from the city, and after Calvin's death, he wrote a biography which severely maligned Calvin's character. In the following year, Joachim Westphal, a Gnesio-Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, condemned Calvin and Zwingli as heretics in denying the eucharistic doctrine of the union of Christ's body with the elements. Calvin's ''Defensio sanae et orthodoxae doctrinae de sacramentis'' (A Defence of the Sober and Orthodox Doctrine of the Sacrament) was his response in 1555. In 1556

Calvin's theology was not without controversy. Pierre Caroli, a Protestant minister in Lausanne accused Calvin, as well as Viret and Farel, of Arianism in 1536. Calvin defended his beliefs on the Trinity in ''Confessio de Trinitate propter calumnias P. Caroli''. In 1551 Jérôme-Hermès Bolsec, a physician in Geneva, attacked Calvin's doctrine of predestination and accused him of making God the author of sin. Bolsec was banished from the city, and after Calvin's death, he wrote a biography which severely maligned Calvin's character. In the following year, Joachim Westphal, a Gnesio-Lutheran pastor in Hamburg, condemned Calvin and Zwingli as heretics in denying the eucharistic doctrine of the union of Christ's body with the elements. Calvin's ''Defensio sanae et orthodoxae doctrinae de sacramentis'' (A Defence of the Sober and Orthodox Doctrine of the Sacrament) was his response in 1555. In 1556 Justus Velsius

Justus Velsius, Haganus, or ''Joost Welsens'' in Dutch (c. 1510, The Hague, Low Countries – after 1581 at an unknown location), was a Dutch humanist, physician, and mathematician.

Velsius started his career as a highly respected professor of li ...

, a Dutch dissident, held a public disputation

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations (in Latin: ''disputationes'', singular: ''disputatio'') offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed ru ...

with Calvin during his visit to Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, in which Velsius defended free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

against Calvin's doctrine of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

. Following the execution of Servetus, a close associate of Calvin, Sebastian Castellio

Sebastian Castellio (also Sébastien Châteillon, Châtaillon, Castellión, and Castello; 1515 – 29 December 1563) was a French preacher and theologian; and one of the first Reformed Christian proponents of religious toleration, freedom of ...

, broke with him on the issue of the treatment of heretics. In Castellio's ''Treatise on Heretics'' (1554), he argued for a focus on Christ's moral teachings in place of the vanity of theology, and he afterward developed a theory of tolerance based on biblical principles.

Calvin and the Jews

Scholars have debated Calvin's view of the Jews and Judaism. Some have argued that Calvin was the least anti-semitic among all the major reformers of his era, especially in comparison to Martin Luther. Others have argued that Calvin was firmly within the anti-semitic camp. Scholars agree, however, that it is important to distinguish between Calvin's views toward the biblical Jews and his attitude toward contemporary Jews. In his theology, Calvin does not differentiate between God's covenant with Israel and the New Covenant. He stated, "all the children of the promise, reborn of God, who have obeyed the commands by faith working through love, have belonged to the New Covenant since the world began." Still he was a supersessionist and argued that the Jews are a rejected people who must embrace Jesus to re-enter the covenant. Most of Calvin's statements on the Jewry of his era were polemical. For example, Calvin once wrote, "I have had much conversation with many Jews: I have never seen either a drop of piety or a grain of truth or ingenuousness – nay, I have never found common sense in any Jew." In this respect, he differed little from other Protestant and Catholic theologians of his time. Among his extant writings, Calvin only dealt explicitly with issues of contemporary Jews and Judaism in one treatise, ''Response to Questions and Objections of a Certain Jew''. In it, he argued that Jews misread their own scriptures because they miss the unity of the Old and New Testaments.Evaluation

''The Encyclopedia of Christianity'' suggests that:/nowiki>Calvin'stheological importance is tied to the attempted systematization of the Christian doctrine. In the doctrine of predestination; in his simple, eschatologically grounded distinction between an immanent and a transcendent eternal work of salvation, resting on Christology and the sacraments; and in his emphasis upon the work of the Holy Spirit in producing the obedience of faith in the regenerate (the ''tertius usus legis'', or so-called third use of the law), he elaborated the orthodoxy that would have a lasting impact on Reformed theology.Erwin Fahlbusch et al., ''The Encyclopedia of Christianity'', vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1999), 324

See also

* Wilhelm Heinrich NeuserNotes

References

*. * (originally published 1965). *. * * * *. * * * *. *. * * *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. {{refend John Calvin Calvinist theologyCalvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvi ...