A Christmas Carol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The phrase " Merry Christmas" had been around for many years – the earliest known written use was in a letter in 1534 – but Dickens's use of the phrase in ''A Christmas Carol'' popularised it among the Victorian public. The exclamation " Bah! Humbug!" entered popular use in the English language as a retort to anything sentimental or overly festive; the name "Scrooge" became used as a designation for a miser and was added to the ''

The phrase " Merry Christmas" had been around for many years – the earliest known written use was in a letter in 1534 – but Dickens's use of the phrase in ''A Christmas Carol'' popularised it among the Victorian public. The exclamation " Bah! Humbug!" entered popular use in the English language as a retort to anything sentimental or overly festive; the name "Scrooge" became used as a designation for a miser and was added to the '' Ruth Glancy, the professor of English literature, states that the largest impact of ''A Christmas Carol'' was the influence felt by individual readers. In early 1844 ''

Ruth Glancy, the professor of English literature, states that the largest impact of ''A Christmas Carol'' was the influence felt by individual readers. In early 1844 ''

* Christmas horror *

''A Christmas Carol'' read online at Bookwise

*

''A Christmas Carol''

at

''A Christmas Carol''

e-book with illustrations

''A Christmas Carol''

Project Gutenberg free online book *

Using Textual Clues to Understand ''A Christmas Carol''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christmas Carol, A 1843 British novels 1840s fantasy novels Articles containing video clips Books illustrated by Arthur Rackham British fantasy novels British novellas British novels adapted into films British novels adapted into plays British novels adapted into television shows Chapman & Hall books Christmas novels English-language novels Ghost novels Novels about time travel Novels adapted into ballets Novels adapted into operas Novels by Charles Dickens Novels set in London Novels set in the 19th century Victorian novels Works about atonement Books illustrated by John Leech

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by

The third spirit, the

The third spirit, the

The writer

The writer

Dickens was not the first author to celebrate the Christmas season in literature. Among earlier authors who influenced Dickens was

Dickens was not the first author to celebrate the Christmas season in literature. Among earlier authors who influenced Dickens was

Dickens was touched by the lot of poor children in the middle decades of the 19th century. In early 1843 he toured the Cornish tin mines, where he was angered by seeing children working in appalling conditions. The suffering he witnessed there was reinforced by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several London schools set up for the education of the capital's half-starved, illiterate street children.

In February 1843 the ''Second Report of the Children's Employment Commission'' was published. It was a parliamentary report exposing the effects of the

Dickens was touched by the lot of poor children in the middle decades of the 19th century. In early 1843 he toured the Cornish tin mines, where he was angered by seeing children working in appalling conditions. The suffering he witnessed there was reinforced by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several London schools set up for the education of the capital's half-starved, illiterate street children.

In February 1843 the ''Second Report of the Children's Employment Commission'' was published. It was a parliamentary report exposing the effects of the

By mid-1843 Dickens began to suffer from financial problems. Sales of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'' were falling off, and his wife,

By mid-1843 Dickens began to suffer from financial problems. Sales of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'' were falling off, and his wife,

The central character of ''A Christmas Carol'' is Ebenezer Scrooge, a miserly London-based businessman, described in the story as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!" Kelly writes that Scrooge may have been influenced by Dickens's conflicting feelings for his father, whom he both loved and demonised. This psychological conflict may be responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale—one a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, the other a benevolent, sociable man. The professor of English literature Robert Douglas-Fairhurst considers that in the opening part of the book covering young Scrooge's lonely and unhappy childhood, and his aspiration for money to avoid poverty "is something of a self-parody of Dickens's fears about himself"; the post-transformation parts of the book are how Dickens optimistically sees himself.

Scrooge could also be based on two misers: the eccentric John Elwes, MP, or Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and also known as "The Gloucester Miser". According to the sociologist Frank W. Elwell, Scrooge's views on the poor are a reflection of those of the

The central character of ''A Christmas Carol'' is Ebenezer Scrooge, a miserly London-based businessman, described in the story as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!" Kelly writes that Scrooge may have been influenced by Dickens's conflicting feelings for his father, whom he both loved and demonised. This psychological conflict may be responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale—one a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, the other a benevolent, sociable man. The professor of English literature Robert Douglas-Fairhurst considers that in the opening part of the book covering young Scrooge's lonely and unhappy childhood, and his aspiration for money to avoid poverty "is something of a self-parody of Dickens's fears about himself"; the post-transformation parts of the book are how Dickens optimistically sees himself.

Scrooge could also be based on two misers: the eccentric John Elwes, MP, or Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and also known as "The Gloucester Miser". According to the sociologist Frank W. Elwell, Scrooge's views on the poor are a reflection of those of the

The transformation of Scrooge is central to the story. Davis considers Scrooge to be "a

The transformation of Scrooge is central to the story. Davis considers Scrooge to be "a

As the result of the disagreements with Chapman and Hall over the commercial failures of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'', Dickens arranged to pay for the publishing himself, in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Production of ''A Christmas Carol'' was not without problems. The first printing was meant to have festive green

As the result of the disagreements with Chapman and Hall over the commercial failures of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'', Dickens arranged to pay for the publishing himself, in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Production of ''A Christmas Carol'' was not without problems. The first printing was meant to have festive green

According to Douglas-Fairhurst, contemporary reviews of ''A Christmas Carol'' "were almost uniformly kind". ''

According to Douglas-Fairhurst, contemporary reviews of ''A Christmas Carol'' "were almost uniformly kind". ''

In January 1844 Parley's Illuminated Library published an unauthorised version of the story in a condensed form which they sold for twopence. Dickens wrote to his solicitor

In January 1844 Parley's Illuminated Library published an unauthorised version of the story in a condensed form which they sold for twopence. Dickens wrote to his solicitor

mime production starring Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, first published in London by Chapman & Hall

Chapman & Hall is an Imprint (trade name), imprint owned by CRC Press, originally founded as a United Kingdom, British publishing house in London in the first half of the 19th century by Edward Chapman (publisher), Edward Chapman and William Hall ...

in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. It recounts the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, an elderly miser

A miser is a person who is reluctant to spend, sometimes to the point of forgoing even basic comforts and some necessities, in order to hoard money or other possessions. Although the word is sometimes used loosely to characterise anyone who ...

who is visited by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley

Jacob Marley is a fictional character in Charles Dickens's 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol'', a former business partner of the miser Ebenezer Scrooge, who has been dead for seven years.Hawes, Donal''Who's Who in Dickens'' Routledge (1998), Goog ...

and the spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come. In the process, Scrooge is transformed into a kinder, gentler man.

Dickens wrote ''A Christmas Carol'' during a period when the British were exploring and re-evaluating past Christmas traditions

Christmas traditions include a variety of customs, religious practices, rituals, and folklore associated with the celebration of Christmas. Many of these traditions vary by country or region, while others are practiced in a virtually identical m ...

, including carols, and newer customs such as cards and Christmas trees

A Christmas tree is a decorated tree, usually an evergreen conifer, such as a spruce, pine or fir, or an artificial tree of similar appearance, associated with the celebration of Christmas. The custom was further developed in early modern ...

. He was influenced by the experiences of his own youth and by the Christmas stories of other authors, including Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

and Douglas Jerrold

Douglas William Jerrold (London 3 January 18038 June 1857 London) was an English dramatist and writer.

Biography

Jerrold's father, Samuel Jerrold, was an actor and lessee of the little theatre of Wilsby near Cranbrook in Kent. In 1807 Dougla ...

. Dickens had written three Christmas stories prior to the novella, and was inspired following a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several establishments for London's street children. The treatment of the poor and the ability of a selfish man to redeem himself by transforming into a more sympathetic character are the key themes of the story. There is discussion among academics as to whether this is a fully secular story, or if it is a Christian allegory.

Published on 19 December, the first edition sold out by Christmas Eve; by the end of 1844 thirteen editions had been released. Most critics reviewed the novella favourably. The story was illicitly copied in January 1844; Dickens took legal action against the publishers, who went bankrupt, further reducing Dickens's small profits from the publication. He subsequently wrote four other Christmas stories. In 1849 he began public readings of the story, which proved so successful he undertook 127 further performances until 1870, the year of his death. ''A Christmas Carol'' has never been out of print and has been translated into several languages; the story has been adapted many times for film, stage, opera and other media.

''A Christmas Carol'' captured the zeitgeist

In 18th- and 19th-century German philosophy, a ''Zeitgeist'' () ("spirit of the age") is an invisible agent, force or Daemon dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in world history.

Now, the term is usually associated with Georg W. ...

of the early Victorian

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

revival of the Christmas holiday. Dickens acknowledged the influence of the modern Western observance of Christmas and later inspired several aspects of Christmas, including family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games and a festive generosity of spirit.

Plot

The book is divided into five chapters, which Dickens titled " staves".Stave one

''A Christmas Carol'' opens on a bleak, cold Christmas Eve in London, seven years after the death of Ebenezer Scrooge's business partner,Jacob Marley

Jacob Marley is a fictional character in Charles Dickens's 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol'', a former business partner of the miser Ebenezer Scrooge, who has been dead for seven years.Hawes, Donal''Who's Who in Dickens'' Routledge (1998), Goog ...

. Scrooge, an ageing miser

A miser is a person who is reluctant to spend, sometimes to the point of forgoing even basic comforts and some necessities, in order to hoard money or other possessions. Although the word is sometimes used loosely to characterise anyone who ...

, dislikes Christmas and refuses a dinner invitation from his nephew Fred. He turns away two men seeking a donation to provide food and heating for the poor and only grudgingly allows his overworked, underpaid clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service ...

, Bob Cratchit

Bob Cratchit is a fictional character in the Charles Dickens 1843 novel ''A Christmas Carol''. The abused, underpaid clerk of Ebenezer Scrooge (and possibly Jacob Marley, when he was alive), Cratchit has come to symbolize the poor working condi ...

, Christmas Day off with pay to conform to the social custom.

That night Scrooge is visited at home by Marley's ghost, who wanders the Earth entwined by heavy chains and money boxes forged during a lifetime of greed and selfishness. Marley tells Scrooge that he has a single chance to avoid the same fate: he will be visited by three spirits and must listen or be cursed to carry much heavier chains of his own.

Stave two

The first spirit, theGhost of Christmas Past

The Ghost of Christmas Past is a fictional character in Charles Dickens' 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol''. The Ghost is one of three spirits which appear to miser Ebenezer Scrooge to offer him a chance of redemption.

Following a visit from ...

, takes Scrooge to Christmas scenes of Scrooge's boyhood, reminding him of a time when he was more innocent. The scenes reveal Scrooge's lonely childhood at boarding school, his relationship with his beloved sister Fan, the long-dead mother of Fred, and a Christmas party hosted by his first employer, Mr Fezziwig

Mr. Fezziwig is a character from the 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol'' created by Charles Dickens to provide contrast with Ebenezer Scrooge's attitudes towards business ethics. Scrooge apprenticed under Fezziwig. Despite this, the older Scrooge s ...

, who treated him like a son. Scrooge's neglected fiancée Belle is shown ending their relationship, as she realises that he will never love her as much as he loves money. Finally, they visit a now-married Belle with her large, happy family on the Christmas Eve that Marley died. Scrooge, upset by hearing Belle's description of the man that he has become, demands that the ghost remove him from the house.

Stave three

The second spirit, theGhost of Christmas Present

The Ghost of Christmas Present is a fictional character in Charles Dickens' 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol''. The Ghost is one of three spirits which appear to miser Ebenezer Scrooge to offer him a chance of redemption.

Following a visit fr ...

, takes Scrooge to a joyous market with people buying the makings of Christmas dinner

Christmas dinner is a meal traditionally eaten at Christmas. This meal can take place any time from the evening of Christmas Eve to the evening of Christmas Day itself. The meals are often particularly rich and substantial, in the tradition of ...

and to celebrations of Christmas in a miner's cottage and in a lighthouse. Scrooge and the ghost also visit Fred's Christmas party. A major part of this stave is taken up with Bob Cratchit's family feast and introduces his youngest son, Tiny Tim, a happy boy who is seriously ill. The spirit informs Scrooge that Tiny Tim will die unless the course of events changes. Before disappearing, the spirit shows Scrooge two hideous, emaciated children named Ignorance and Want. He tells Scrooge to beware the former above all and mocks Scrooge's concern for their welfare.

Stave four

The third spirit, the

The third spirit, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come

The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a fictional character in Charles Dickens's 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol''. The Ghost is one of three spirits which appear to miser Ebenezer Scrooge to offer him a chance of redemption.

Following a vis ...

, shows Scrooge a Christmas Day in the future. The silent ghost reveals scenes involving the death of a disliked man whose funeral is attended by local businessmen only on condition that lunch is provided. His charwoman

A charwoman (also chargirl, charlady or char) is an old-fashioned occupational term, referring to a paid part-time worker who comes into a house or other building to clean it for a few hours of a day or week, as opposed to a maid, who usually ...

, laundress

A washerwoman or laundress is a woman who takes in laundry. Both terms are now old-fashioned; equivalent work nowadays is done by a laundry worker in large commercial premises, or a laundrette (laundromat) attendant.

Description

As evidenced ...

and the local undertaker

A funeral director, also known as an undertaker (British English) or mortician (American English), is a professional involved in the business of funeral rites. These tasks often entail the embalming and burial or cremation of the dead, as ...

steal his possessions to sell to a fence

A fence is a structure that encloses an area, typically outdoors, and is usually constructed from posts that are connected by boards, wire, rails or netting. A fence differs from a wall in not having a solid foundation along its whole length.

...

. When he asks the spirit to show a single person who feels emotion over his death, he is only given the pleasure of a poor couple who rejoice that his death gives them more time to put their finances in order. When Scrooge asks to see tenderness connected with any death, the ghost shows him Bob Cratchit and his family mourning the death of Tiny Tim. The ghost then allows Scrooge to see a neglected grave, with a tombstone bearing Scrooge's name. Sobbing, Scrooge pledges to change his ways.

Stave five

Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning a changed man. He makes a large donation to the charity he rejected the previous day, anonymously sends a large turkey to the Cratchit home for Christmas dinner and spends the afternoon at Fred's Christmas party. The following day he gives Cratchit an increase in pay, and begins to become a father figure to Tiny Tim. From then on Scrooge treats everyone with kindness, generosity and compassion, embodying the spirit of Christmas.Background

The writer

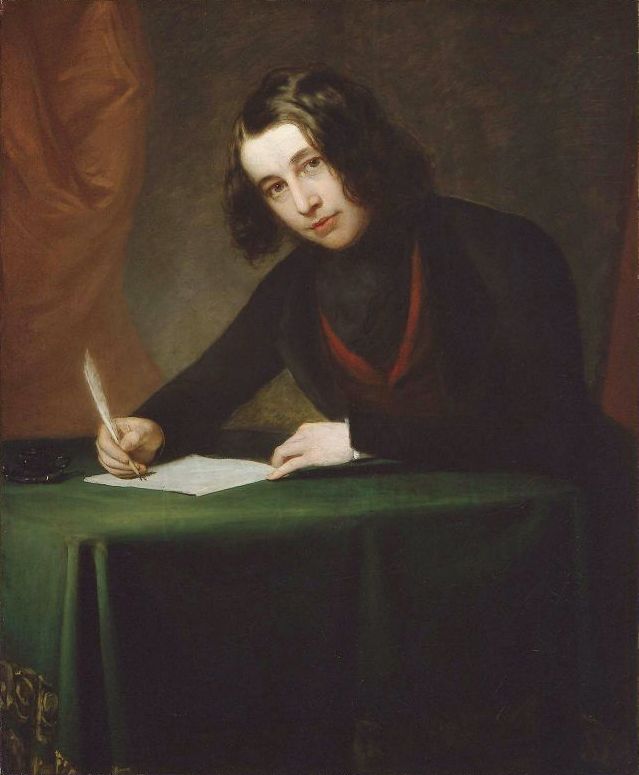

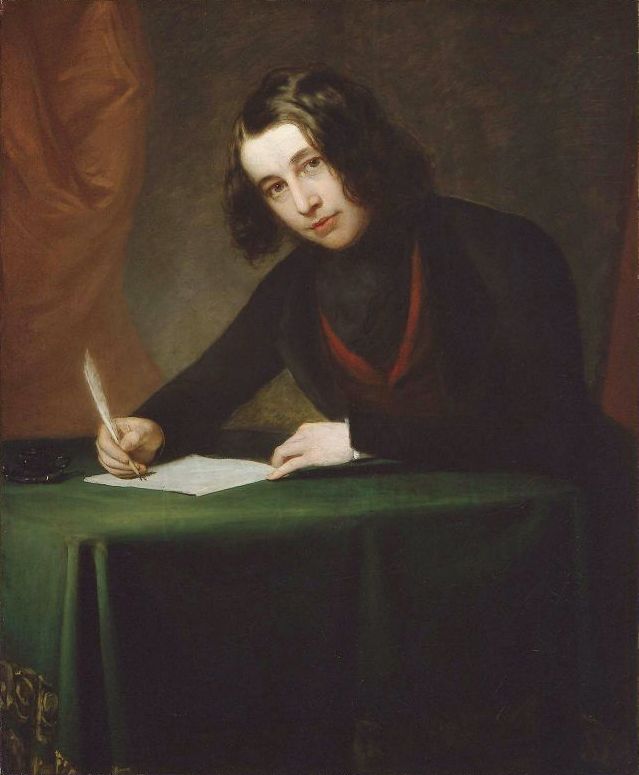

The writer Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

was born to a middle-class family which got into financial difficulties as a result of the spendthrift nature of his father John. In 1824 John was committed to the Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, ...

, a debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histori ...

in Southwark, London. Dickens, aged 12, was forced to pawn

Pawn most often refers to:

* Pawn (chess), the weakest and most numerous piece in the game

* Pawnbroker or pawnshop, a business that provides loans by taking personal property as collateral

Pawn may also refer to:

Places

* Pawn, Oregon, an his ...

his collection of books, leave school and work at a dirty and rat-infested shoe-blacking factory. The change in circumstances gave him what his biographer, Michael Slater, describes as a "deep personal and social outrage", which heavily influenced his writing and outlook.

By the end of 1842 Dickens was a well-established author with six major works as well as several short stories, novellas and other pieces. On 31 December that year he began publishing his novel ''Martin Chuzzlewit

''The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit'' (commonly known as ''Martin Chuzzlewit'') is a novel by Charles Dickens, considered the last of his picaresque novels. It was originally serialised between 1842 and 1844. While he was writing it ...

'' as a monthly serial; it was his favourite work, but sales were disappointing and he faced temporary financial difficulties.

Celebrating the Christmas season

The Christmas season or the festive season (also known in some countries as the holiday season or the holidays) is an annually recurring period recognized in many Western and other countries that is generally considered to run from late November ...

had been growing in popularity through the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. The Christmas tree was introduced in Britain during the 18th century, and its use was popularised by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

and Prince Albert. In the early 19th century there had been a revival of interest in Christmas carols

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year, ...

, following a decline in popularity over the previous hundred years. The publication of Davies Gilbert

Davies Gilbert (born Davies Giddy, 6 March 1767 – 24 December 1839) was an English engineer, author, and politician. He was elected to the Royal Society on 17 November 1791 and served as President of the Royal Society from 1827 to 1830. He ...

's 1823 work ''Some Ancient Christmas Carols, With the Tunes to Which They Were Formerly Sung in the West of England'' and William Sandys's 1833 collection ''Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern'' led to a growth in the form's popularity in Britain.

Dickens had an interest in Christmas, and his first story on the subject was "Christmas Festivities", published in '' Bell's Weekly Messenger'' in 1835; the story was then published as "A Christmas Dinner" in ''Sketches by Boz

''Sketches by "Boz," Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People'' (commonly known as ''Sketches by Boz'') is a collection of short pieces Charles Dickens originally published in various newspapers and other periodicals between 1833 and ...

'' (1836). "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton", another Christmas story, appeared in the 1836 novel ''The Pickwick Papers

''The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club'' (also known as ''The Pickwick Papers'') was Charles Dickens's first novel. Because of his success with '' Sketches by Boz'' published in 1836, Dickens was asked by the publisher Chapman & Hall to ...

''. In the episode, a Mr Wardle describes a misanthropic sexton, Gabriel Grub, who undergoes a Christmas conversion after being visited by goblin

A goblin is a small, grotesque, monstrous creature that appears in the folklore of multiple European cultures. First attested in stories from the Middle Ages, they are ascribed conflicting abilities, temperaments, and appearances depending on ...

s who show him the past and future. Slater considers that "the main elements of the ''Carol'' are present in the story", but not yet in a firm form. The story is followed by a passage about Christmas in Dickens's editorial ''Master Humphrey's Clock

''Master Humphrey's Clock'' was a weekly periodical edited and written entirely by Charles Dickens and published from 4 April 1840 to 4 December 1841. It began with a frame story in which Master Humphrey tells about himself and his small circle ...

''. The professor of English literature Paul Davis writes that although the "Goblins" story appears to be a prototype of ''A Christmas Carol'', all Dickens's earlier writings about Christmas influenced the story.

Literary influences

Dickens was not the first author to celebrate the Christmas season in literature. Among earlier authors who influenced Dickens was

Dickens was not the first author to celebrate the Christmas season in literature. Among earlier authors who influenced Dickens was Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

, whose 1819–20 work ''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.

''The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.'', commonly referred to as ''The Sketch Book'', is a collection of 34 essays and short stories written by the American author Washington Irving. It was published serially throughout 1819 and 1820. The co ...

'' included four essays on old English Christmas traditions

Christmas traditions include a variety of customs, religious practices, rituals, and folklore associated with the celebration of Christmas. Many of these traditions vary by country or region, while others are practiced in a virtually identical m ...

that he experienced while staying at Aston Hall

Aston Hall is a Grade I listed Jacobean house in Aston, Birmingham, England, designed by John Thorpe and built between 1618 and 1635. It is a leading example of the Jacobean prodigy house.

In 1864, the house was bought by Birmingham Corpor ...

near Birmingham. The tales and essays attracted Dickens, and the two authors shared the belief that returning to Christmas traditions might promote a type of social connection that they felt had been lost in the modern world.

Several works may have had an influence on the writing of ''A Christmas Carol'', including two Douglas Jerrold

Douglas William Jerrold (London 3 January 18038 June 1857 London) was an English dramatist and writer.

Biography

Jerrold's father, Samuel Jerrold, was an actor and lessee of the little theatre of Wilsby near Cranbrook in Kent. In 1807 Dougla ...

essays: one from an 1841 issue of ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'', "How Mr. Chokepear Keeps a Merry Christmas" and one from 1843, "The Beauties of the Police". More broadly, Dickens was influenced by fairy tales and nursery stories, which he closely associated with Christmas, because he saw them as stories of conversion and transformation.

Social influences

Dickens was touched by the lot of poor children in the middle decades of the 19th century. In early 1843 he toured the Cornish tin mines, where he was angered by seeing children working in appalling conditions. The suffering he witnessed there was reinforced by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several London schools set up for the education of the capital's half-starved, illiterate street children.

In February 1843 the ''Second Report of the Children's Employment Commission'' was published. It was a parliamentary report exposing the effects of the

Dickens was touched by the lot of poor children in the middle decades of the 19th century. In early 1843 he toured the Cornish tin mines, where he was angered by seeing children working in appalling conditions. The suffering he witnessed there was reinforced by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several London schools set up for the education of the capital's half-starved, illiterate street children.

In February 1843 the ''Second Report of the Children's Employment Commission'' was published. It was a parliamentary report exposing the effects of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

upon working class children. Horrified by what he read, Dickens planned to publish an inexpensive political pamphlet tentatively titled, ''An Appeal to the People of England, on behalf of the Poor Man's Child'', but changed his mind, deferring the pamphlet's production until the end of the year. In March he wrote to Dr Southwood Smith

Thomas Southwood Smith (17881861) was an English physician and sanitary reformer.

Early life

Smith was born at Martock, Somerset, into a strict Baptist family, his parents being William Smith and Caroline Southwood. In 1802 he won a scholarshi ...

, one of the four commissioners responsible for the ''Second Report'', about his change in plans: "you will certainly feel that a Sledge hammer has come down with twenty times the force—twenty thousand times the force—I could exert by following out my first idea".

In a fundraising speech on 5 October 1843 at the Manchester Athenaeum

The Athenaeum in Princess Street Manchester, England, now part of Manchester Art Gallery, was originally a club built for the Manchester Athenaeum, a society for the "advancement and diffusion of knowledge", in 1837. The society, founded in 1 ...

, Dickens urged workers and employers to join together to combat ignorance with educational reform, and realised in the days following that the most effective way to reach the broadest segment of the population with his social concerns about poverty and injustice was to write a deeply felt Christmas narrative rather than polemical pamphlets and essays.

Writing history

By mid-1843 Dickens began to suffer from financial problems. Sales of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'' were falling off, and his wife,

By mid-1843 Dickens began to suffer from financial problems. Sales of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'' were falling off, and his wife, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, was pregnant with their fifth child. Matters worsened when Chapman & Hall

Chapman & Hall is an Imprint (trade name), imprint owned by CRC Press, originally founded as a United Kingdom, British publishing house in London in the first half of the 19th century by Edward Chapman (publisher), Edward Chapman and William Hall ...

, his publishers, threatened to reduce his monthly income by £50 if sales dropped further. He began ''A Christmas Carol'' in October 1843. Michael Slater, Dickens's biographer, describes the book as being "written at white heat"; it was completed in six weeks, the final pages being written in early December. He built much of the work in his head while taking night-time walks of around London. Dickens's sister-in-law wrote how he "wept, and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner, in composition". Slater says that ''A Christmas Carol'' was

intended to open its readers' hearts towards those struggling to survive on the lower rungs of the economic ladder and to encourage practical benevolence, but also to warn of the terrible danger to society created by the toleration of widespread ignorance and actual want among the poor.

George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank (27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reache ...

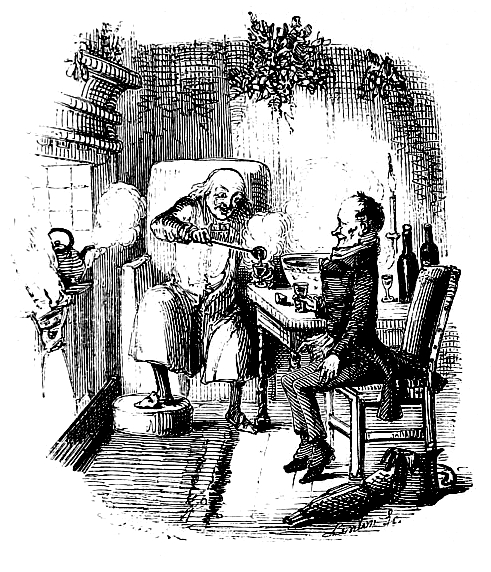

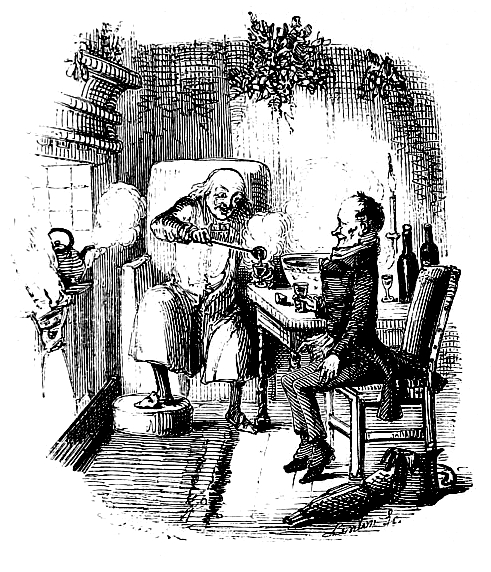

, the illustrator who had earlier worked with Dickens on ''Sketches by Boz'' (1836) and '' Oliver Twist'' (1838), introduced him to the caricaturist John Leech. By 24 October Dickens invited Leech to work on ''A Christmas Carol'', and four hand-coloured etchings and four black-and-white wood engravings by the artist accompanied the text. Dickens's hand-written manuscript of the story does not include the sentence in the penultimate paragraph "... and to Tiny Tim, who did ''not'' die"; this was added later, during the printing process.

Characters

The central character of ''A Christmas Carol'' is Ebenezer Scrooge, a miserly London-based businessman, described in the story as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!" Kelly writes that Scrooge may have been influenced by Dickens's conflicting feelings for his father, whom he both loved and demonised. This psychological conflict may be responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale—one a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, the other a benevolent, sociable man. The professor of English literature Robert Douglas-Fairhurst considers that in the opening part of the book covering young Scrooge's lonely and unhappy childhood, and his aspiration for money to avoid poverty "is something of a self-parody of Dickens's fears about himself"; the post-transformation parts of the book are how Dickens optimistically sees himself.

Scrooge could also be based on two misers: the eccentric John Elwes, MP, or Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and also known as "The Gloucester Miser". According to the sociologist Frank W. Elwell, Scrooge's views on the poor are a reflection of those of the

The central character of ''A Christmas Carol'' is Ebenezer Scrooge, a miserly London-based businessman, described in the story as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!" Kelly writes that Scrooge may have been influenced by Dickens's conflicting feelings for his father, whom he both loved and demonised. This psychological conflict may be responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale—one a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, the other a benevolent, sociable man. The professor of English literature Robert Douglas-Fairhurst considers that in the opening part of the book covering young Scrooge's lonely and unhappy childhood, and his aspiration for money to avoid poverty "is something of a self-parody of Dickens's fears about himself"; the post-transformation parts of the book are how Dickens optimistically sees himself.

Scrooge could also be based on two misers: the eccentric John Elwes, MP, or Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and also known as "The Gloucester Miser". According to the sociologist Frank W. Elwell, Scrooge's views on the poor are a reflection of those of the demographer

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

and political economist

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour m ...

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, while the miser's questions "Are there no prisons? ... And the Union workhouses? ... The treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?" are a reflection of a sarcastic question raised by the philosopher Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, "Are there not treadmills, gibbets; even hospitals, poor-rates, New Poor-Law?"

There are literary precursors for Scrooge in Dickens's own works. Peter Ackroyd

Peter Ackroyd (born 5 October 1949) is an English biographer, novelist and critic with a specialist interest in the history and culture of London. For his novels about English history and culture and his biographies of, among others, William ...

, Dickens's biographer, sees similarities between the character and the elder Martin Chuzzlewit character, although the miser is "a more fantastic image" than the Chuzzlewit patriarch; Ackroyd observes that Chuzzlewit's transformation to a charitable figure is a parallel to that of the miser. Douglas-Fairhurst sees that the minor character Gabriel Grub from ''The Pickwick Papers'' was also an influence when creating Scrooge. It is possible that Scrooge's name came from a tombstone Dickens had seen on a visit to Edinburgh. The grave was for Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie, whose job was given as a meal man—a corn merchant; Dickens misread the inscription as "mean man". This theory has been described as "a probable Dickens hoax" for which " one could find any corroborating evidence".

When Dickens was young he lived near a tradesman's premises with the sign "Goodge and Marney", which may have provided the name for Scrooge's former business partner. For the chained Marley, Dickens drew on his memory of a visit to the Western Penitentiary

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

* Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Pennsylvania, in March 1842, where he saw—and was affected by seeing—fettered prisoners. For the character Tiny Tim, Dickens used his nephew Henry, a disabled boy who was five at the time ''A Christmas Carol'' was written. The two figures of Want and Ignorance, sheltering in the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present, were inspired by the children Dickens had seen on his visit to a ragged school in the East End of London.

Themes

The transformation of Scrooge is central to the story. Davis considers Scrooge to be "a

The transformation of Scrooge is central to the story. Davis considers Scrooge to be "a protean

In Greek mythology, Proteus (; Ancient Greek: Πρωτεύς, ''Prōteus'') is an early prophetic sea-god or god of rivers and oceanic bodies of water, one of several deities whom Homer calls the " Old Man of the Sea" ''(hálios gérôn) ...

figure always in process of reformation"; Kelly writes that the transformation is reflected in the description of Scrooge, who begins as a two-dimensional character, but who then grows into one who "possess san emotional depth nda regret for lost opportunities". Some writers, including the Dickens scholar Grace Moore, consider that there is a Christian theme running through ''A Christmas Carol'', and that the novella should be seen as an allegory of the Christian concept of redemption. Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin, sees the conversion of Scrooge as carrying the Christian message that "even the worst of sinners may repent and become a good man". Dickens's attitudes towards organised religion were complex; he based his beliefs and principles on the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

. His statement that Marley "had no bowels" is a reference to the "bowels of compassion" mentioned in the First Epistle of John

The First Epistle of John is the first of the Johannine epistles of the New Testament, and the fourth of the catholic epistles. There is no scholarly consensus as to the authorship of the Johannine works. The author of the First Epistle is ter ...

, the reason for his eternal damnation.

Other writers, including Kelly, consider that Dickens put forward a "secular vision of this sacred holiday". The Dickens scholar John O. Jordan argues that ''A Christmas Carol'' shows what Dickens referred to in a letter to his friend John Forster as his "''Carol'' philosophy, cheerful views, sharp anatomisation of humbug, jolly good temper ... and a vein of glowing, hearty, generous, mirthful, beaming reference in everything to Home and Fireside". From a secular viewpoint, the cultural historian Penne Restad suggests that Scrooge's redemption underscores "the conservative, individualistic and patriarchal aspects" of Dickens's "''Carol'' philosophy" of charity

Charity may refer to:

Giving

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

* C ...

and altruism.

Dickens wrote ''A Christmas Carol'' in response to British social attitudes towards poverty, particularly child poverty

Child poverty refers to the state of children living in poverty and applies to children from poor families and orphans being raised with limited or no state resources. UNICEF estimates that 356 million children live in extreme poverty. It's est ...

, and wished to use the novella as a means to put forward his arguments against it. The story shows Scrooge as a paradigm for self-interest, and the possible repercussions of ignoring the poor, especially children—personified by the allegorical figures of Want and Ignorance. The two figures were created to arouse sympathy with readers—as was Tiny Tim. Douglas-Fairhurst observes that the use of such figures allowed Dickens to present his message of the need for charity without alienating his largely middle-class readership.

Publication

As the result of the disagreements with Chapman and Hall over the commercial failures of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'', Dickens arranged to pay for the publishing himself, in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Production of ''A Christmas Carol'' was not without problems. The first printing was meant to have festive green

As the result of the disagreements with Chapman and Hall over the commercial failures of ''Martin Chuzzlewit'', Dickens arranged to pay for the publishing himself, in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Production of ''A Christmas Carol'' was not without problems. The first printing was meant to have festive green endpapers

The endpapers or end-papers of a book (also known as the endsheets) are the pages that consist of a double-size sheet folded, with one half pasted against an inside cover (the pastedown), and the other serving as the first free page (the free end ...

, but they came out a dull olive colour. Dickens' publisher Chapman and Hall replaced these with yellow endpapers and reworked the title page in harmonising red and blue shades. The final product was bound in red cloth with gilt-edged pages, completed only two days before the publication date of 19 December 1843. Following publication, Dickens arranged for the manuscript to be bound in red Morocco leather

Morocco leather (also known as Levant, the French Maroquin, or German Saffian from Safi, a Moroccan town famous for leather) is a vegetable-tanned leather known for its softness, pliability, and ability to take color. It has been widely used in ...

and presented as a gift to his solicitor, Thomas Mitton.

Priced at five shillings (equal to £ in pounds), the first run of 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve. Chapman and Hall issued second and third editions before the new year, and the book continued to sell well into 1844. By the end of 1844 eleven more editions had been released. Since its initial publication the book has been issued in numerous hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and has never been out of print. It was Dickens's most popular book in the United States, and sold over two million copies in the hundred years following its first publication there.

The high production costs upon which Dickens insisted led to reduced profits, and the first edition brought him only £230 (equal to £ in pounds) rather than the £1,000 (equal to £ in pounds) he expected. A year later, the profits were only £744, and Dickens was deeply disappointed.

Reception

According to Douglas-Fairhurst, contemporary reviews of ''A Christmas Carol'' "were almost uniformly kind". ''

According to Douglas-Fairhurst, contemporary reviews of ''A Christmas Carol'' "were almost uniformly kind". ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication i ...

'' described how the story's "impressive eloquence ... its unfeigned lightness of heart—its playful and sparkling humour ... its gentle spirit of humanity" all put the reader "in good humour with ourselves, with each other, with the season and with the author". The critic from '' The Athenaeum'', the literary magazine, considered it a "tale to make the reader laugh and cry – to open his hands, and open his heart to charity even toward the uncharitable ... a dainty dish to set before a King." William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

, writing in ''Fraser's Magazine

''Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country'' was a general and literary journal published in London from 1830 to 1882, which initially took a strong Tory line in politics. It was founded by Hugh Fraser and William Maginn in 1830 and loosely directe ...

'', described the book as "a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness. The last two people I heard speak of it were women; neither knew the other, or the author, and both said, by way of criticism, 'God bless him!'"

The poet Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humorist, best known for poems such as " The Bridge of Sighs" and " The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for ''The London Magazine'', '' Athenaeum'', and ''Punch' ...

, in his own journal, wrote that "If Christmas, with its ancient and hospitable customs, its social and charitable observances, were ever in danger of decay, this is the book that would give them a new lease." The reviewer for ''Tait's Edinburgh Magazine

''Tait's Edinburgh Magazine'' was a monthly periodical founded in 1832. It was an important venue for liberal political views, as well as contemporary cultural and literary developments, in early-to-mid-nineteenth century Britain.

The magazine wa ...

''—Theodore Martin

Sir Theodore Martin (16 September 1816 – 18 August 1909) was a Scottish poet, biographer, and translator.

Biography

Martin was the son of James Martin, a solicitor in Edinburgh, where Theodore was born and educated at the Royal High Scho ...

, who was usually critical of Dickens's work—spoke well of ''A Christmas Carol'', noting it was "a noble book, finely felt and calculated to work much social good". After Dickens's death, Margaret Oliphant

Margaret Oliphant Wilson Oliphant (born Margaret Oliphant Wilson; 4 April 1828 – 20 June 1897) was a Scottish novelist and historical writer, who usually wrote as Mrs. Oliphant. Her fictional works cover "domestic realism, the historical nove ...

deplored the turkey and plum pudding aspects of the book but admitted that in the days of its first publication it was regarded as "a new gospel", and noted that the book was unique in that it made people behave better. The religious press generally ignored the tale but, in January 1844, '' Christian Remembrancer'' thought the tale's old and hackneyed subject was treated in an original way and praised the author's sense of humour and pathos. The writer and social thinker John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

told a friend that he thought Dickens had taken the religion from Christmas, and had imagined it as "mistletoe and pudding – neither resurrection from the dead, nor rising of new stars, nor teaching of wise men, nor shepherds".

There were critics of the book. ''The New Monthly Magazine

''The New Monthly Magazine'' was a British monthly magazine published from 1814 to 1884. It was founded by Henry Colburn and published by him through to 1845.

History

Colburn and Frederic Shoberl established ''The New Monthly Magazine and Univ ...

'' praised the story, but thought the book's physical excesses—the gilt edges and expensive binding—kept the price high, making it unavailable to the poor. The review recommended that the tale should be printed on cheap paper and priced accordingly. An unnamed writer for ''The Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal unti ...

'' mocked Dickens's grasp of economics, asking "Who went without turkey and punch in order that Bob Cratchit might get them—for, unless there were turkeys and punch in surplus, someone must go without".

Dickens had criticised the US in ''American Notes

''American Notes for General Circulation'' is a travelogue by Charles Dickens detailing his trip to North America from January to June 1842. While there he acted as a critical observer of North American society, almost as if returning a status r ...

'' and ''Martin Chuzzlewit'', making American readers reluctant to embrace his work, but by the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the book had gained wide recognition in American households. In 1863 ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' published an enthusiastic review, noting that the author brought the "old Christmas ... of bygone centuries and remote manor houses, into the living rooms of the poor of today".

Aftermath

In January 1844 Parley's Illuminated Library published an unauthorised version of the story in a condensed form which they sold for twopence. Dickens wrote to his solicitor

In January 1844 Parley's Illuminated Library published an unauthorised version of the story in a condensed form which they sold for twopence. Dickens wrote to his solicitor

I have not the least doubt that if these Vagabonds can be stopped they must. ... Let us be the ''sledge-hammer'' in this, or I shall be beset by hundreds of the same crew when I come out with a long story.Two days after the release of the Parley version, Dickens sued on the basis of

copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, s ...

and won. The publishers declared themselves bankrupt and Dickens was left to pay £700 in costs. The small profits Dickens earned from ''A Christmas Carol'' further strained his relationship with his publishers, and he broke with them in favour of Bradbury and Evans, who had been printing his works to that point.

Dickens returned to the tale several times during his life to amend the phrasing and punctuation. He capitalised on the success of the book by publishing other Christmas stories: ''The Chimes

''The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In'', commonly referred to as ''The Chimes'', is a novella written by Charles Dickens and first published in 1844, one year after ''A Christmas Carol''. It is th ...

'' (1844), ''The Cricket on the Hearth

''The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home'' is a novella by Charles Dickens, published by Bradbury and Evans, and released 20 December 1845 with illustrations by Daniel Maclise, John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield and Edwin ...

'' (1845), '' The Battle of Life'' (1846) and ''The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain

''The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain, A Fancy for Christmas-Time'' (better known as ''The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain'' or simply as ''The Haunted Man'') is a novella by Charles Dickens first published in 1848. It is the fifth and ...

'' (1848); these were secular conversion tales which acknowledged the progressive societal changes of the previous year, and highlighted those social problems which still needed to be addressed. While the public eagerly bought the later books, the reviewers were highly critical of the stories.

Performances and adaptations

By 1849 Dickens was engaged with ''David Copperfield

''David Copperfield'' Dickens invented over 14 variations of the title for this work, see is a novel in the bildungsroman genre by Charles Dickens, narrated by the eponymous David Copperfield, detailing his adventures in his journey from inf ...

'' and had neither the time nor the inclination to produce another Christmas book. He decided the best way to reach his audience with his "Carol philosophy" was by public readings. During Christmas 1853 he gave a reading in Birmingham Town Hall to the Industrial and Literary Institute. He insisted that tickets be reserved for working-class attendees at quarter-price and the performance was a great success. Thereafter, he read the tale in an abbreviated version 127 times, until 1870 (the year of his death), including at his farewell performance.

In the years following the book's publication, responses to the tale were published by W. M. Swepstone (''Christmas Shadows'', 1850), Horatio Alger (''Job Warner's Christmas'', 1863), Louisa May Alcott (''A Christmas Dream, and How It Came True'', 1882), and others who followed Scrooge's life as a reformed man – or some who thought Dickens had got it wrong and needed to be corrected.

The novella was adapted for the stage almost immediately. Three productions opened on 5 February 1844, one by Edward Stirling, '' A Christmas Carol; or, Past, Present, and Future'', being sanctioned by Dickens and running for more than 40 nights. By the close of February 1844 eight rival ''A Christmas Carol'' theatrical productions were playing in London. The story has been adapted for film and television more than any of Dickens's other works. In 1901 it was produced as ''Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost

''Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost'' is a 1901 British short silent drama film, directed by Walter R. Booth, featuring the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge (played by Daniel Smith) confronted by Jacob Marley's ghost and given visions of Christmas past, p ...

'', a silent black-and-white

Black-and-white (B&W or B/W) images combine black and white in a continuous spectrum, producing a range of shades of grey.

Media

The history of various visual media began with black and white, and as technology improved, altered to color. ...

British film; it was one of the first known adaptations of a Dickens work on film, but it is now largely lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

*Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

* Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

. The story was adapted in 1923 for BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

. It has been adapted to other media, including opera, ballet, animation, stage musicals and a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Marcel Marceau

Marcel Marceau (; born Marcel Mangel; 22 March 1923 – 22 September 2007) was a French actor and mime artist most famous for his stage persona, "Bip the Clown". He referred to mime as the "art of silence", and he performed professionally worldw ...

.

Davis considers the adaptations have become better remembered than the original. Some of Dickens's scenes—such as visiting the miners and lighthouse keepers—have been forgotten by many, while other events often added—such as Scrooge visiting the Cratchits on Christmas Day—are now thought by many to be part of the original story. Accordingly, Davis distinguishes between the original text and the "remembered version".

Legacy

The phrase " Merry Christmas" had been around for many years – the earliest known written use was in a letter in 1534 – but Dickens's use of the phrase in ''A Christmas Carol'' popularised it among the Victorian public. The exclamation " Bah! Humbug!" entered popular use in the English language as a retort to anything sentimental or overly festive; the name "Scrooge" became used as a designation for a miser and was added to the ''

The phrase " Merry Christmas" had been around for many years – the earliest known written use was in a letter in 1534 – but Dickens's use of the phrase in ''A Christmas Carol'' popularised it among the Victorian public. The exclamation " Bah! Humbug!" entered popular use in the English language as a retort to anything sentimental or overly festive; the name "Scrooge" became used as a designation for a miser and was added to the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a co ...

'' as such in 1982.

In the early 19th century the celebration of Christmas was associated in Britain with the countryside and peasant revels, disconnected to the increasing urbanisation and industrialisation taking place. Davis considers that in ''A Christmas Carol'', Dickens showed that Christmas could be celebrated in towns and cities, despite increasing modernisation. The modern observance of Christmas in English-speaking countries is largely the result of a Victorian-era revival of the holiday. The Oxford Movement of the 1830s and 1840s had produced a resurgence of the traditional rituals and religious observances associated with Christmastide

Christmastide is a season of the liturgical year in most Christian churches. In some, Christmastide is identical to Twelvetide.

For the Catholic Church, Lutheran Church, Anglican Church and Methodist Church, Christmastide begins on 24 December ...

and, with ''A Christmas Carol'', Dickens captured the zeitgeist

In 18th- and 19th-century German philosophy, a ''Zeitgeist'' () ("spirit of the age") is an invisible agent, force or Daemon dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in world history.

Now, the term is usually associated with Georg W. ...

while he reflected and reinforced his vision of Christmas.

Dickens advocated a humanitarian focus of the holiday, which influenced several aspects of Christmas that are still celebrated in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games and a festive generosity of spirit. The historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 b ...

writes that Dickens "linked worship and feasting, within a context of social reconciliation".

The novelist William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

, analysing several of Dickens's Christmas stories, including ''A Christmas Carol'', considered that by 1891 the "pathos appears false and strained; the humor largely horseplay; the characters theatrical; the joviality pumped; the psychology commonplace; the sociology alone funny". The writer James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

considered that Dickens took a childish approach with ''A Christmas Carol'', producing a gap between the naïve optimism of the story and the realities of life at the time.

Ruth Glancy, the professor of English literature, states that the largest impact of ''A Christmas Carol'' was the influence felt by individual readers. In early 1844 ''

Ruth Glancy, the professor of English literature, states that the largest impact of ''A Christmas Carol'' was the influence felt by individual readers. In early 1844 ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term '' magazine'' (from the French ''magazine ...

'' attributed a rise of charitable giving in Britain to Dickens's novella; in 1874, Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

, after reading Dickens's Christmas books, vowed to give generously to those in need, and Thomas Carlyle expressed a generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after reading the book. In 1867 one American businessman was so moved by attending a reading that he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey, while in the early years of the 20th century Maud of Wales

Maud of Wales (Maud Charlotte Mary Victoria; 26 November 1869 – 20 November 1938) was the Queen of Norway as the wife of King Haakon VII. The youngest daughter of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, she was known as P ...

– the Queen of Norway

The list of Norwegian monarchs ( no, kongerekken or ''kongerekka'') begins in 872: the traditional dating of the Battle of Hafrsfjord, after which victorious King Harald Fairhair merged several petty kingdoms into that of his father. Named after ...

– sent gifts to London's crippled children signed "With Tiny Tim's Love". On the novella, the author G. K. Chesterton wrote "The beauty and blessing of the story ... lie in the great furnace of real happiness that glows through Scrooge and everything around him. ... Whether the Christmas visions would or would not convert Scrooge, they convert us."

Analysing the changes made to adaptations over time, Davis sees changes to the focus of the story and its characters to reflect mainstream thinking of the period. While Dickens's Victorian audiences would have viewed the tale as a spiritual but secular parable, in the early 20th century it became a children's story, read by parents who remembered their parents reading it when they were younger. In the lead-up to and during the Great Depression, Davis suggests that while some saw the story as a "denunciation of capitalism, ...most read it as a way to escape oppressive economic realities". The film versions of the 1930s were different in the UK and US. British-made films showed a traditional telling of the story, while US-made works showed Cratchit in a more central role, escaping the depression caused by European bankers and celebrating what Davis calls "the Christmas of the common man". In the 1960s, Scrooge was sometimes portrayed as a Freudian figure wrestling with his past. By the 1980s he was again set in a world of depression and economic uncertainty.

See also

* Christmas horror *

List of Christmas-themed literature

The following is a navigational list of notable literary works which are set at Christmas time, or contain Christmas amongst the central themes.

Novels and novellas

*Agatha Christie, ''Hercule Poirot's Christmas''

*Charles Dickens, ''A Christmas C ...

* Dickens Christmas fair

* '' The Man Who Invented Christmas''

Notes

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Online resources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Newspapers, journals and magazines

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''A Christmas Carol'' read online at Bookwise

*

''A Christmas Carol''

at

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

''A Christmas Carol''

e-book with illustrations

''A Christmas Carol''

Project Gutenberg free online book *

Using Textual Clues to Understand ''A Christmas Carol''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christmas Carol, A 1843 British novels 1840s fantasy novels Articles containing video clips Books illustrated by Arthur Rackham British fantasy novels British novellas British novels adapted into films British novels adapted into plays British novels adapted into television shows Chapman & Hall books Christmas novels English-language novels Ghost novels Novels about time travel Novels adapted into ballets Novels adapted into operas Novels by Charles Dickens Novels set in London Novels set in the 19th century Victorian novels Works about atonement Books illustrated by John Leech