The Revolutionist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"The Revolutionist" is an

"The Revolutionist" is an

The piece was probably written in 1923 or 1924, when Hemingway lived in Paris with his first wife

The piece was probably written in 1923 or 1924, when Hemingway lived in Paris with his first wife

Of the six references to Mantegna in the entire Hemingway canon, two occur in "The Revolutionist".Johnston (1971), 87 Mentioning Mantegna twice in such a very short story signals it is an important point; critics think Hemingway almost certainly meant Mantegna's c. 1501 ''Dead Christ'', which deviates greatly from Giotto and Masaccio and della Francesco in its use of perspective and realism.Tetlow, 132 The picture depicts Christ in death as a very human figure with a robust physiognomy in the days before resurrection and ascension. Critic Kenneth Johnston says that for a Renaissance viewer the painting would have a much different effect than for a young man of the

Of the six references to Mantegna in the entire Hemingway canon, two occur in "The Revolutionist".Johnston (1971), 87 Mentioning Mantegna twice in such a very short story signals it is an important point; critics think Hemingway almost certainly meant Mantegna's c. 1501 ''Dead Christ'', which deviates greatly from Giotto and Masaccio and della Francesco in its use of perspective and realism.Tetlow, 132 The picture depicts Christ in death as a very human figure with a robust physiognomy in the days before resurrection and ascension. Critic Kenneth Johnston says that for a Renaissance viewer the painting would have a much different effect than for a young man of the

''A reader ́s guide to Ernest Hemingway''

Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Ernest Hemingway Collection, JFK Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revolutionist 1925 short stories Modernist short stories Short stories by Ernest Hemingway Italy in fiction

"The Revolutionist" is an

"The Revolutionist" is an Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

short story published in his first American volume of stories ''In Our Time In Our Time may refer to:

* ''In Our Time'' (1944 film), a film starring Ida Lupino and Paul Henreid

* ''In Our Time'' (1982 film), a Taiwanese anthology film featuring director Edward Yang; considered the beginning of the "New Taiwan Cinema"

* ''In ...

''. Originally written as a vignette for his earlier Paris edition of the collection, titled ''in our time'', he rewrote and expanded the piece for the 1925 American edition published by Boni & Liveright

Boni & Liveright (pronounced "BONE-eye" and "LIV-right") is an American trade book publisher established in 1917 in New York City by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright. Over the next sixteen years the firm, which changed its name to Horace Live ...

. It is only one of two vignettes rewritten as short stories for the American edition.

The story is about a young Hungarian magyar communist revolutionary fleeing the Hungarian White Terror to Italy. There he visits museums, where he sees some Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

paintings he likes, while declaring his dislike for the painter Mantegna.

"The Revolutionist" has received scant attention from literary critics with only a cursory examination of the art mentioned in the short story. Literary critics have speculated whether Hemingway's intended meaning in his allusion to Mantegna's '' Dead Christ'' is meant to highlight the importance of realism as opposed to idealism, or whether it is a reminder of the character's pain and perhaps the pain suffered by an entire generation.

Summary

In the story a Magyar communist revolutionist travels by train through Italy visiting art galleries. He admiresGiotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/ Proto-Renaissance period. G ...

, Masaccio

Masaccio (, , ; December 21, 1401 – summer 1428), born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, was a Florentine artist who is regarded as the first great Italian painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance. According to Vasar ...

, and Piero della Francesca, but not Mantegna. He buys reproductions of the pieces he likes, which he wraps and stows carefully. When he reports to a second character, who acts as the story's narrator, the two take a train to Romagna

Romagna ( rgn, Rumâgna) is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna, North Italy. Traditionally, it is limited by the Apennines to the south-west, the Adriatic to th ...

. The narrator then sends the young man on to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

from where he is to cross to safety across the Alps into Switzerland via Aosta

Aosta (, , ; french: Aoste , formerly ; frp, Aoûta , ''Veulla'' or ''Ouhta'' ; lat, Augusta Praetoria Salassorum; wae, Augschtal; pms, Osta) is the principal city of Aosta Valley, a bilingual region in the Italian Alps, north-northwest o ...

. The narrator provides him with addresses for contacts in Milan and tells him about the Montegnas to be seen there—which the young Communist again explains he dislikes. The story ends with the narrator saying: "The last I heard of him the Swiss had him in a jail near Sion."Hemingway (1925), 82

Publication history and background

The piece was probably written in 1923 or 1924, when Hemingway lived in Paris with his first wife

The piece was probably written in 1923 or 1924, when Hemingway lived in Paris with his first wife Hadley Richardson

Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (November 9, 1891 – January 22, 1979) was the first wife of American author Ernest Hemingway. The two married in 1921 after a courtship of less than a year, and moved to Paris within months of being married. In Paris, ...

. A year earlier all of his manuscripts were lost when Hadley packed them in a suitcase that was stolen. Acting on Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

's advice that he had lost no more than the time it took to write the pieces, Hemingway either recreated them or wrote new vignettes and stories.Smith (1996), 40–42

"The Revolutionist" was included as a vignette (Chapter 11) in the 1924 Paris edition of ''in our time In Our Time may refer to:

* ''In Our Time'' (1944 film), a film starring Ida Lupino and Paul Henreid

* ''In Our Time'' (1982 film), a Taiwanese anthology film featuring director Edward Yang; considered the beginning of the "New Taiwan Cinema"

* ''In ...

'' published by Bill Bird

William Augustus Bird (1888–1963) was an American journalist, now remembered for his Three Mountains Press, a small press he ran while in Paris in the 1920s for the Consolidated Press Association. Taken over by Nancy Cunard in 1928, it bec ...

's Three Mountain's Press.Mellow (1992), 239 Of the 18 vignettes contained in the volume, only two were rewritten as short stories for the American edition, published in 1925 by Boni & Liveright

Boni & Liveright (pronounced "BONE-eye" and "LIV-right") is an American trade book publisher established in 1917 in New York City by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright. Over the next sixteen years the firm, which changed its name to Horace Live ...

. "The Revolutionist" was one; the other was "A Very Short Story

"A Very Short Story" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. It was first published as a vignette, or chapter, in the 1924 Paris edition titled '' In Our Time'', and later rewritten and added to Hemingway's first American short story collec ...

".

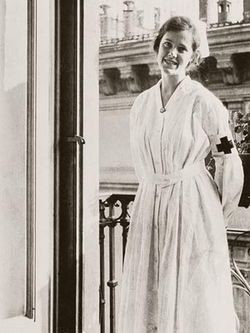

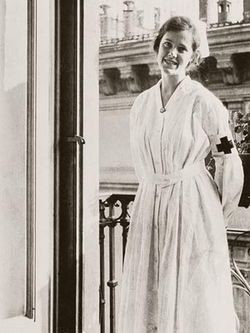

It has autobiographical allusions to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. In 1918, at age 19 Hemingway recuperated for six months at a hospital in Milan after suffering a mortar hit on the Italian front. There, Hemingway met and fell in love with Red Cross nurse Agnes von Kurowsky

Agnes Hannah von Kurowsky Stanfield (January 5, 1892 – November 25, 1984) was an American nurse who inspired the character "Catherine Barkley" in Ernest Hemingway's 1929 novel ''A Farewell to Arms''.

Kurowsky served as a nurse in an American Re ...

. Although seven years his senior, Hemingway loved her deeply and the two were to marry on his return to the US at the end of his recuperation.Meyers (1985), 37–42 However, after Hemingway went home, he was devastated when Kurowsky broke off the romance in a letter,Oliver (1999), 189-190 telling him of her engagement to an Italian officer.

The background of "The Revolutionist" is based on the 1919 Hungarian White Terror, caused when Communist iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be consid ...

resulted in a bloody and violent backlash leading to a period of severe repression, from which the young Magyar revolutionist flees.

Style and themes

At barely over a page long, (no more than 400 words) the piece is variously considered a vignette or a story. It lacks a plot, and seemingly does no more than capture a moment of time in the characters' lives. The piece is an early experiment in Hemingway's "theory of omission"—later to be known as theIceberg Theory

The iceberg theory or theory of omission is a writing technique coined by American writer Ernest Hemingway. As a young journalist, Hemingway had to focus his newspaper reports on immediate events, with very little context or interpretation. When h ...

—in which nonessential information is left out or barely hinted at.Oliver (1999), 279–280 The story has attracted little attention from literary critics and much of that examines the allusions to Renaissance painters.Sanderson (2006), 98 Early biographers such as Carlos Baker

Carlos Baker (May 5, 1909, Biddeford, Maine – April 18, 1987, Princeton, New Jersey) was an American writer, biographer and former Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature at Princeton University. He received his B.A. from Dartmouth College and ...

dismissed the piece as a miniature, or a sketch.

Hemingway was an art lover. He said that "seeing pictures" was one of five things he cared about, going on to say, "And I could remember all the pictures."Johnston (1971), 86 Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

caused a minor literary dispute when he made derisive remarks about Hemingway's allusion to the "bitter nail holes" of Mantegna's ''Dead Christ'' in ''A Farewell to Arms

''A Farewell to Arms'' is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant () in the a ...

''; Hemingway shot back by saying that the characters the writer makes must genuinely be interested in the art, clearly explaining, "A writer who appreciates the seriousness of writing so little that he is anxious to make the reader see he is formally educated, cultured and well-bred is merely a pop-in-jay."

Of the six references to Mantegna in the entire Hemingway canon, two occur in "The Revolutionist".Johnston (1971), 87 Mentioning Mantegna twice in such a very short story signals it is an important point; critics think Hemingway almost certainly meant Mantegna's c. 1501 ''Dead Christ'', which deviates greatly from Giotto and Masaccio and della Francesco in its use of perspective and realism.Tetlow, 132 The picture depicts Christ in death as a very human figure with a robust physiognomy in the days before resurrection and ascension. Critic Kenneth Johnston says that for a Renaissance viewer the painting would have a much different effect than for a young man of the

Of the six references to Mantegna in the entire Hemingway canon, two occur in "The Revolutionist".Johnston (1971), 87 Mentioning Mantegna twice in such a very short story signals it is an important point; critics think Hemingway almost certainly meant Mantegna's c. 1501 ''Dead Christ'', which deviates greatly from Giotto and Masaccio and della Francesco in its use of perspective and realism.Tetlow, 132 The picture depicts Christ in death as a very human figure with a robust physiognomy in the days before resurrection and ascension. Critic Kenneth Johnston says that for a Renaissance viewer the painting would have a much different effect than for a young man of the lost generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort in the Western world that was in early adulthood during World War I. "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in th ...

"who would see ... an acute reminder that life if painful and painfully short." Hemingway was fascinated by scenes of the crucifixion, according to Johnston, seeing it symbolic of sacrifice, "the ultimate in pain, suffering and courage", writing that to Hemingway's young man in "The Revolutionist", "the bitter nail holes of Mantegna's Christ symbolize the painful price of sacrifice".

Hemingway scholar Charles Oliver speculates Mantegna's social rise from humble beginnings could be construed as offensive to the young communist's values. Critics suggest the young Magyar's dislike of the artist means he rejects Mantegna's realism while conversely the narrator embraces Mantegna and his realism. Johnston believes the young man has seen and experienced deep suffering and wishes to avoid the visual imagery of the "bitter nail holes" "for they would painfully recall the 'bad things' he and his comrades suffered in their revolutionary faith."

Critic Anthony Hunt thinks the artists and their works is unimportant to the story, and the piece shows the revolutionist as an idealistic young man more attracted to the countryside of Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

and less to cities such as Milan; hence Mantegna merely symbolizes a place.Tetlow (1992), 132 Johnston disagrees. He believes the young man is a Hemingway archetype, a character whose idealism has been shattered, who has experienced the horrors of war, and who copes by ignoring or avoiding images and situations that remind him of his past. He has entered a state of "non-thinking". Hunt finds it significant that the young man keeps the reproductions of artists rejected by the Communist party well-wrapped in ''Avanti!

''Avanti!'' is a 1972 American/Italian international co-production comedy film produced and directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills. The screenplay by Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond is based on Samuel A. Taylor's play, ...

'', the Italian socialist newspaper.

Hunt, furthermore, points out Milan is significant because in that city, where he was hospitalized after his wounding, Hemingway experienced his first romantic disappointment from Agnes von Kurowsky.

References

Sources

* Hemingway, Ernest (1925). ''In Our Time''. New York: Scribner. * Mellow, James (1992). ''Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences''. New York: Houghton Mifflin. * Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). ''Hemingway: A Biography''. New York: Macmillan. * Oliver, Charles (1999). ''Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work''. New York: Checkmark Publishing. * Sanderson, Rena (2006). ''Hemingway's Italy: New Perspectives''. Louisiana State University Press * Smith, Paul (1996). "1924: Hemingway's Luggage and the Miraculous Year". in Donaldson, Scott (ed). ''The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway''. New York: Cambridge UP. * Tetlow, Wendolyn E. (1992). ''Hemingway's "In Our Time": Lyrical Dimensions''. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. * Waldhorn, Arthur (2002 edition)''A reader ́s guide to Ernest Hemingway''

Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

External links

Ernest Hemingway Collection, JFK Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revolutionist 1925 short stories Modernist short stories Short stories by Ernest Hemingway Italy in fiction