The Rage Against God on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Rage Against God'' (subtitle in US editions: ''How Atheism Led Me to Faith'') is the fifth book by

In Chapter 1, Hitchens describes abandoning religion in his youth, and promoting "cruel revolutionary rubbish" as a

In Chapter 1, Hitchens describes abandoning religion in his youth, and promoting "cruel revolutionary rubbish" as a

In Chapter 9, Hitchens contends that the claim that religion is a source of conflict is a "cruel factual misunderstanding", and that a number of conflicts, including

In Chapter 9, Hitchens contends that the claim that religion is a source of conflict is a "cruel factual misunderstanding", and that a number of conflicts, including

Hitchens writes "the biggest fake miracle staged in human history was the claim that the Soviet Union was a new civilisation of equality, peace, love, truth, science and progress. Everyone knows that it was a prison, a slum, a return to primitive barbarism, a kingdom of lies where scientists and doctors feared offending the secret police, and that its elite were corrupt and lived in secret luxury". He then cites

Hitchens writes "the biggest fake miracle staged in human history was the claim that the Soviet Union was a new civilisation of equality, peace, love, truth, science and progress. Everyone knows that it was a prison, a slum, a return to primitive barbarism, a kingdom of lies where scientists and doctors feared offending the secret police, and that its elite were corrupt and lived in secret luxury". He then cites

https://nationalpost.com/Yahweh+youngsters/3339589/story.html] Three extracts from ''The Rage Against God'' published by the Canadian

Video interview (produced by Zondervan) with Peter Hitchens about the book

Text of radio interview between Peter Hitchens and Hugh Hewitt, discussing ''The Rage Against God'' and the decline of Christianity in the West

Review of the book by Diane Scharper in the '' National Catholic Reporter'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Rage Against God 2010 non-fiction books 2010 in Christianity Books about atheism Books by Peter Hitchens Christian apologetic works Criticism of New Atheism Continuum International Publishing Group books Zondervan books

Peter Hitchens

Peter Jonathan Hitchens (born 28 October 1951) is an English author, broadcaster, journalist, and commentator. He writes for '' The Mail on Sunday'' and was a foreign correspondent reporting from both Moscow and Washington, D.C. Peter Hitchens ...

, first published in 2010. The book describes Hitchens's journey from atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

, far-left politics

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars conside ...

, and bohemianism

Bohemianism is the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people and with few permanent ties. It involves musical, artistic, literary, or spiritual pursuits. In this context, bohemians may be wanderers, a ...

to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

and conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, detailing the influences on him that led to his conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

. The book is partly intended as a response to '' God Is Not Great'', a book written by his brother Christopher Hitchens in 2007.

Peter Hitchens, with particular reference to events which occurred in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, argues that his brother's verdict on religion is misguided, and that faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

in God is both a safeguard against the collapse of civilisation into moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

chaos and the best antidote to what he views as the dangerous idea of earthly perfection through utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

nism. ''The Rage Against God'' received a mostly favourable reception in the media.

Background

In May 2009 ''The Rage Against God'' was anticipated byMichael Gove

Michael Andrew Gove (; born Graeme Andrew Logan, 26 August 1967) is a British politician serving as Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Minister for Intergovernmental Relations since 2021. He has been Member of Par ...

, who wrote in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'':

Hitchens first referred to ''The Rage Against God'' in August 2009, in one of his weekly columns: "Above all, I seek to counter the assertion, central to my brother's case ... that the Soviet regime was in fact religious in character. This profound misunderstanding of the nature of the USSR is the key to finding another significant flaw in what is in general his circular argument". Then, a week before the book's publication, Hitchens wrote: "...it is obvious much of what I say n The Rage Against Godarises out of my attempt to debate religion with him hristopher Hitchens it would be absurd to pretend that much of what I say here is not intended to counter or undermine arguments he presented in his book, God Is Not Great...".

Synopsis

Part One: A Personal Journey Through Atheism

In Chapter 1, Hitchens describes abandoning religion in his youth, and promoting "cruel revolutionary rubbish" as a

In Chapter 1, Hitchens describes abandoning religion in his youth, and promoting "cruel revolutionary rubbish" as a Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

activist. He claims his generation had become intellectually aloof from religion, rebellious and disillusioned and in Chapter 2 explores further reasons for this disillusion, including the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

and the Profumo affair. In Chapter 3, Hitchens recounts how he embraced scientific inquiry and adopted liberal positions on issues such as marriage, abortion, homosexuality, and patriotism. Chapter 4 is a lament for the "noble austerity" of his childhood in Britain. Chapter 5 explores what Hitchens views as the pseudo-religion surrounding Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

heroes – a "great cult of noble, patriotic death" whose only equivalent, he claims, was in the Soviet Union. Hitchens then asserts that, "The Christian Church has been powerfully damaged by letting itself be confused with love of country and the making of great wars".

In Chapter 6, Hitchens recalls being a foreign correspondent in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and a trip to Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

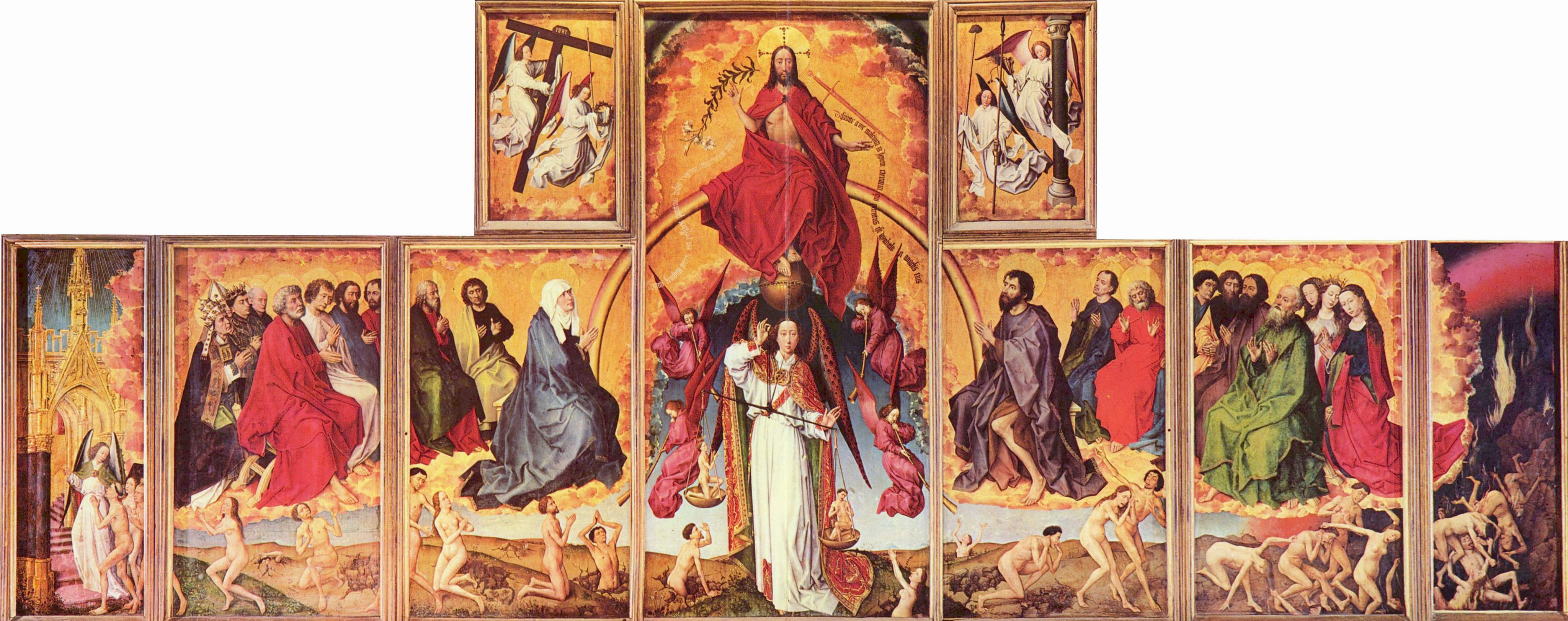

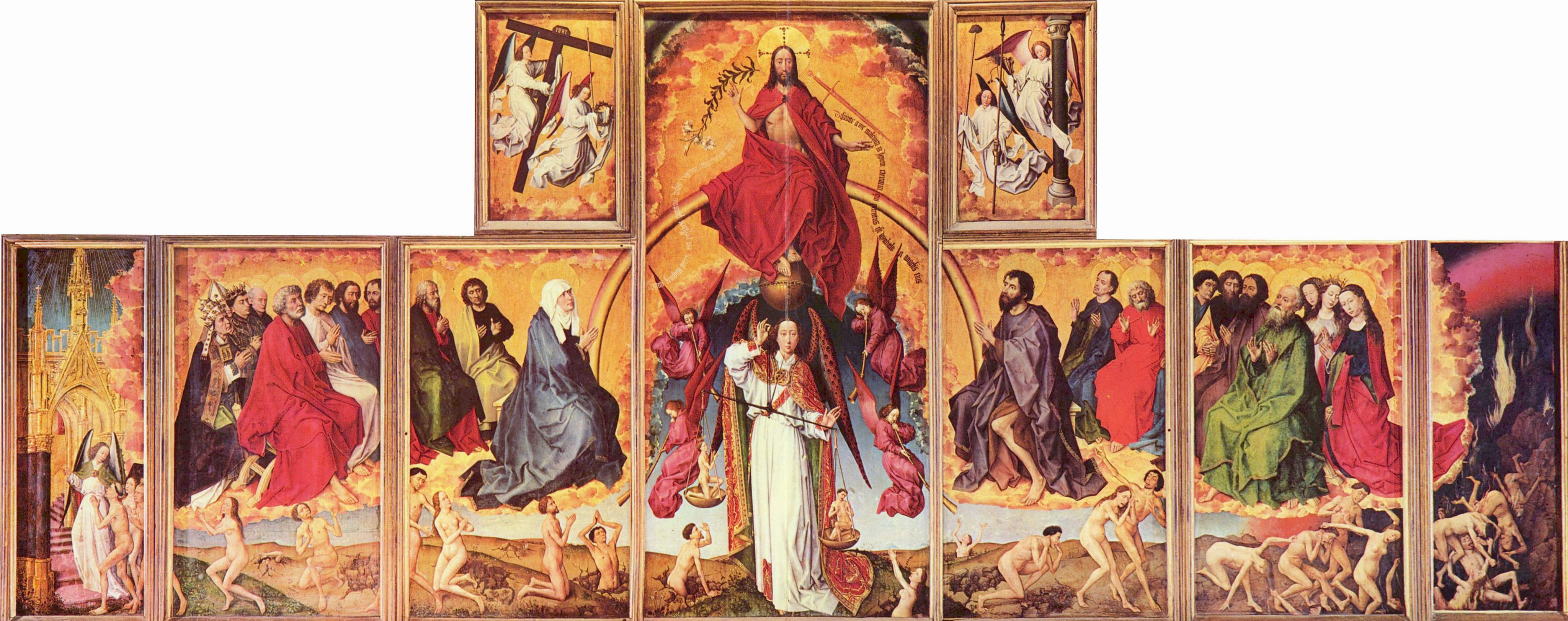

, and how these experiences convinced him that, "his own civilisation was infinitely precious and utterly vulnerable". In Chapter 7, Hitchens charts his return to Christianity, and makes particular reference to the experience of seeing the Rogier van der Weyden painting '' The Last Judgement'': "I gaped, my mouth actually hanging open. These people did not appear remote or from the ancient past; they were my own generation ... I had absolutely no doubt I was among the damned". In Chapter 8, Hitchens examines the diminishing of Christianity in Britain and its potential causes.

Part Two: Addressing Atheism: Three Failed Arguments

The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

and the Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by th ...

, were not motivated by religion but tribal in nature and disputes over territory. Chapter 10 discusses whether morality can be determined without the concept of God

Conceptions of God in monotheist, pantheist, and panentheist religions – or of the supreme deity in henotheistic religions – can extend to various levels of abstraction:

* as a powerful, personal, supernatural being, or as the d ...

. Hitchens asserts that atheists "have a fundamental inability to concede that to be effectively absolute, a moral code needs to be beyond human power to alter". He also describes as flawed his brother's assertion in ''God is Not Great'' that "the order to love thy neighbour 'as thyself' is too extreme and too strenuous to be obeyed". Hitchens ends the chapter by stating, "in all my experience in life, I have seldom seen a more powerful argument for the fallen nature of man, and his inability to achieve perfection, than those countries in which man sets himself up to replace God with the State".

Hitchens begins Chapter 11 by asserting, "those who reject God's absolute authority, preferring their own, are far more ready to persecute than Christians have been ... Each revolutionary generation reliably repeats the savagery". He cites as examples the French revolutionary terror; the Bolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

; the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

and the Soviet famine of 1932–33; the barbarity surrounding Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's five-year plans, repeated in the Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstr ...

in China; atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 ...

; and human rights abuses in Cuba under Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

. Hitchens then quotes a number of prominent communist thinkers' pronouncements on morality, including George Lukacs stating, "Communist ethics make it the highest duty to accept the necessity of acting wickedly. This is the greatest sacrifice the revolution asks from us", and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

's claiming that "morality, more than any other form of ideology, has a class character".

Part Three: The League of the Militant Godless

Hitchens writes "the biggest fake miracle staged in human history was the claim that the Soviet Union was a new civilisation of equality, peace, love, truth, science and progress. Everyone knows that it was a prison, a slum, a return to primitive barbarism, a kingdom of lies where scientists and doctors feared offending the secret police, and that its elite were corrupt and lived in secret luxury". He then cites

Hitchens writes "the biggest fake miracle staged in human history was the claim that the Soviet Union was a new civilisation of equality, peace, love, truth, science and progress. Everyone knows that it was a prison, a slum, a return to primitive barbarism, a kingdom of lies where scientists and doctors feared offending the secret police, and that its elite were corrupt and lived in secret luxury". He then cites Walter Duranty

Walter Duranty (25 May 1884 – 3 October 1957) was an Anglo-American journalist who served as Moscow bureau chief of '' The New York Times'' for fourteen years (1922–1936) following the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War (1918� ...

's denying the existence of the great Ukrainian famine, and Sidney and Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term ''collective bargaining''. She ...

's acceptance that the 1937 Moscow show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so ...

s were "genuine criminal prosecutions". Hitchens then examines Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's suppression of religion in the Soviet Union, which included making the teaching of religion to children punishable by the death penalty and the creation of an antireligious organisation of Soviet workers. Hitchens begins Chapter 13 by quoting William Henry Chamberlin: "In Russia, the world is witnessing the first effort to destroy completely any belief in supernatural interpretation of life", and then examines some consequences of this, including intolerance of religion, terror, and the persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these ter ...

of priests and bishops at the Solovetsky concentration camp. Hitchens asserts that in the Soviet Union "the regime's institutional loathing for the teaching of religion, and its desire to eradicate it, survived every doctrinal detour and swerve".

In the final chapter, Hitchens analyses a number of his brother's arguments, and contends that "the coincidence in instinct, taste, and thought between my brother and the Bolsheviks and their sympathisers is striking and undeniable". He then records how his brother nominated the "apostle of revolutionary terror" Leon Trotsky for an edition of the BBC radio series ''Great Lives

''Great Lives'' is a BBC Radio 4 biography series, produced in Bristol. It has been presented by Joan Bakewell, Humphrey Carpenter, Francine Stock and currently (since April 2006) Matthew Parris. A distinguished guest is asked to nominate the pe ...

''; praised Trotsky for his "moral courage"; and declared that one of Lenin's great achievements was "to create a secular Russia". Hitchens speculates that his brother remained sympathetic towards Bolshevism and is still hostile towards the things it extirpated, including monarchy, tradition, and faith. He ends the chapter by claiming a form of militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin ...

secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a si ...

is becoming established in Britain, and that "The Rage Against God is loose".

Epilogue

In the epilogue, Hitchens describes how after a 2008 debate with his brother Christopher that "the longest quarrel of my life seemed to be unexpectedly over" and that he held no hope of converting his brother, who had "bricked himself up high in his atheist tower, with slits instead of windows from which to shoot arrows at the faithful".Critical reception

After its UK publication in March 2010 the book received a number of mostly favourable reviews in British newspapers. In ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' Christopher Howse concentrated on the moral arguments in the book, and agreed with Hitchens that "to determine what is right and what is wrong without God, is difficult". Also in ''The Daily Telegraph'', Charles Moore wrote that the book "tries to do two things at once. One is to bash up modern militant atheism with all the author's polemical skill. The other is to give an autobiographical account of how, in our time, an intelligent man's faith may recover". In a positive review in '' Standpoint'' magazine, Michael Nazir Ali wrote, "One of the abiding canards nailed by Peter Hitchens is that religion causes conflict. He does this by showing that so-called "religious" wars had many other elements to them, such as greed for territory, political ambition and nationalism. His repeated references to Soviet brutality reveal that secular ideologies have caused more suffering in recent times than any conflict associated with religion." In a more critical review in the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' Sholto Byrnes wrote, "Hitchens makes his case forcefully, passionately and intelligently", but "makes too much connection between the ill deeds of atheists and their atheism". Byrnes also reviewed the book in ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'', where he questioned the validity of a number of Hitchens's conclusions, including that "atheists 'actively wish for disorder and meaninglessness'".

In a sympathetic review in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', Rupert Shortt wrote, "Hitchens does not seek to mount a comprehensive defence of Christianity. He is wise to avoid deeper philosophical and theological waters, because his strengths lie elsewhere. His more manageable aim is to expose what he holds to be three major fallacies underlying ''God Is Not Great'': that conflict fought in the name of religion is really always about faith; that "it is ultimately possible to know with confidence what is right and what is wrong without acknowledging the existence of God"; and that "atheist states are not actually atheist". In ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''Th ...

'', Quentin Letts reviewed the book very positively, describing it as "a magnificent, sustained cry against the aggressive secularism taking control of our weakened culture".

Reviews of the book in North American publications subsequent to its stateside release were more mixed.

In ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Mark Oppenheimer commented, "American readers will notice a lack of enthusiasm in Peter's Christian apologetics. He proceeds largely from historical, rather than personal, evidence: here are the fruits of Christianity, and here is what one finds in its absence". In a negative review in the ''Winnipeg Free Press

The ''Winnipeg Free Press'' (or WFP; founded as the ''Manitoba Free Press'') is a daily (excluding Sunday) broadsheet newspaper in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. It provides coverage of local, provincial, national, and international news, as well as ...

'', Ted St. Godard wrote, "What Hitchens can't seem to appreciate is that, even if 'Soviet Communism is organically linked to atheism, something his brother and others argue against (if somewhat feebly), and even if one accepts that Soviet tyranny was horrible, this says little about the existence of God". In a '' Washington Times'' review entitled "Cain and Abel: The sequel?", Jeremy Lott wrote, "Hitchens refuses to make a full-throated case for faith. He explains that 'those who choose to argue in prose... are unlikely to be receptive to a case that is most effectively couched in poetry' ... Peter does hope that Christopher might one day arrive at some sort of acceptance that belief in God is not necessarily a character fault—and that religion does not poison everything".

One mix of the two audiences is the British writer, Theodore Dalrymple

Anthony Malcolm Daniels (born 11 October 1949), also known by the pen name Theodore Dalrymple (), is a conservative English cultural critic, prison physician and psychiatrist. He worked in a number of Sub-Saharan African countries as well as in ...

, reviewing ''The Rage Against God'' and Christopher Hitchens' '' Hitch-22'' for the American journal ''First Things

''First Things'' (''FT'') is an ecumenical and conservative religious journal aimed at "advanc nga religiously informed public philosophy for the ordering of society". The magazine, which focuses on theology, liturgy, church history, religi ...

''. Dalrymple writes, Peter Hitchens "has discovered that it is he, and not just the world, that was and is imperfect and that therefore humility is a virtue, even if one does not always live up to it. The first sentence of his first chapter reads, "I set fire to my Bible on the playing fields of my Cambridge boarding school one bright, windy spring afternoon in 1967". One senses the deep—and, in my view, healthy—feeling of self-disgust with which he wrote this, for indeed it describes an act of wickedness. Peter's memoir...is more personally searching."[]

Release details

The book was first published in the UK on 15 March 2010 by Continuum Publishing Corporation, and was released in the US in June 2010 by Zondervan, with the additional subtitle ''How Atheism Led Me to Faith''.See also

* Christian apologetics * Criticism of atheism * Human rights in the Soviet UnionReferences

Bibliography

* * *Further reading

*External links

https://nationalpost.com/Yahweh+youngsters/3339589/story.html] Three extracts from ''The Rage Against God'' published by the Canadian

National Post

The ''National Post'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet newspaper available in several cities in central and western Canada. The paper is the flagship publication of Postmedia Network and is published Mondays through Saturdays, with ...

in July 2010Video interview (produced by Zondervan) with Peter Hitchens about the book

Text of radio interview between Peter Hitchens and Hugh Hewitt, discussing ''The Rage Against God'' and the decline of Christianity in the West

Review of the book by Diane Scharper in the '' National Catholic Reporter'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Rage Against God 2010 non-fiction books 2010 in Christianity Books about atheism Books by Peter Hitchens Christian apologetic works Criticism of New Atheism Continuum International Publishing Group books Zondervan books