The Grand Exchange on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the

The first manifestation of the Columbian exchange may have been the spread of

The first manifestation of the Columbian exchange may have been the spread of

The

The

Although large-scale use of wheels did not occur in the Americas prior to European contact, numerous small wheeled artifacts, identified as children's toys, have been found in Mexican archeological sites, some dating to approximately 1500 BCE. Some argue that the primary obstacle to large-scale development of the wheel in the Americas was the absence of domesticated large animals that could be used to pull wheeled carriages. The closest relative of

Although large-scale use of wheels did not occur in the Americas prior to European contact, numerous small wheeled artifacts, identified as children's toys, have been found in Mexican archeological sites, some dating to approximately 1500 BCE. Some argue that the primary obstacle to large-scale development of the wheel in the Americas was the absence of domesticated large animals that could be used to pull wheeled carriages. The closest relative of

Initially at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals.

Initially at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals.

One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of

One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of

Elusive Lager Yeast Found in Patagonia

''Discovery News'', August 23, 2011 Others have crossed the Atlantic to Europe and have changed the course of history. In the 1840s, ''

The Columbian Exchange: Plants, Animals, and Disease between the Old and New Worlds

by Alfred W. Crosby (2009)

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

by Charles C. Mann (2006)

Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World

by Jack Weatherford (2010)

Worlds Together, Worlds Apart

by Jeremy Adelman, Stephen Aron, Stephen Kotkin, et al.

Foods that Changed the World

by Steven R. King from the

The Columbian Exchange

video, study guide, analysis, and teaching guide {{DEFAULTSORT:Columbian exchange Agricultural revolutions History of agriculture History of Europe History of globalization History of indigenous peoples of the Americas History of the Americas Horticulture Introduced species Invasive species Spanish colonization of the Americas Spanish exploration in the Age of Discovery History of the Atlantic Ocean Transatlantic cultural exchange Age of Discovery

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

(the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

) in the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

, and the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

(Afro-Eurasia

Afro-Eurasia (also Afroeurasia, Eurafrasia or the Old World) is a landmass comprising the continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe. The terms are compound words of the names of its constituent parts. Its mainland is the largest and most popul ...

) in the Eastern Hemisphere

The Eastern Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth which is east of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and west of the antimeridian (which crosses the Pacific Ocean and relatively little land from pole ...

, in the late 15th and following centuries. It is named after the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

and is related to the European colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense be ...

and global trade following his 1492 voyage. Some of the exchanges were purposeful; some were accidental or unintended. Communicable diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dis ...

of Old World origin resulted in an 80 to 95 percent reduction in the number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

from the 15th century onwards, most severely in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. The cultures of both hemispheres were significantly impacted by the migration of people (both free and enslaved) from the Old World to the New. European colonists and African slaves

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean ...

replaced Indigenous populations across the Americas, to varying degrees. The number of Africans taken to the New World was far greater than the number of Europeans moving to the New World in the first three centuries after Columbus.

The new contacts among the global population resulted in the interchange of a wide variety of crop

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. When the plants of the same kind are cultivated at one place on a large scale, it is called a crop. Most crops are cultivated in agriculture or hydropon ...

s and livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

, which supported increases in food production and population in the Old World. American crops such as maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

es, tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

es, tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

, sweet potatoes

The sweet potato or sweetpotato ('' Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young sho ...

, and chili pepper

Chili peppers (also chile, chile pepper, chilli pepper, or chilli), from Nahuatl '' chīlli'' (), are varieties of the berry-fruit of plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for ...

s became important crops around the world. Old World rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and '' Porteresia'', both wild and domesticat ...

, wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

, and livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

, among other crops, became important in the New World. American-produced silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

flooded the world and became the standard metal used in coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order ...

age, especially in Imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

.

The term was first used in 1972 by the American historian and professor Alfred W. Crosby in his environmental history

Environmental history is the study of human interaction with the natural world over time, emphasising the active role nature plays in influencing human affairs and vice versa.

Environmental history first emerged in the United States out of th ...

book '' The Columbian Exchange''. It was rapidly adopted by other historians and journalists.

Etymology

In 1972 Alfred W. Crosby, an American historian at theUniversity of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

, published the book '' The Columbian Exchange'', and subsequent volumes within the same decade. His primary focus was mapping the biological and cultural transfers that occurred between the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

and New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

s. He studied the effects of Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

's voyages between the two – specifically, the global diffusion of crops, seeds, and plants from the New World to the Old, which radically transformed agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

in both regions. His research made a lasting contribution to the way scholars understand the variety of contemporary ecosystems that arose due to these transfers.

The term has become popular among historians and journalists and has since been enhanced with Crosby's later book in three editions, ''Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900''. Charles C. Mann

Charles C. Mann (born 1955) is an American journalist and author, specializing in scientific topics. In 2006 his book '' 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus'' won the National Academies Communication Award for best book of the ...

, in his book ''1493

Year 1493 ( MCDXCIII) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* January 19 – Treaty of Barcelona: Charles VIII of France returns Cerdagne a ...

'' further expands and updates Crosby's original research.

Background

The weight of scientific evidence is that humans first came to the New World fromSiberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

thousands of years ago. There is little additional evidence of contacts between the peoples of the Old World and those of the New World, although the literature speculating on pre-Columbian trans-oceanic journeys is extensive. The first inhabitants of the New World brought with them domestic dogs and, possibly, a container, the calabash

Calabash (; ''Lagenaria siceraria''), also known as bottle gourd, white-flowered gourd, long melon, birdhouse gourd, New Guinea bean, Tasmania bean, and opo squash, is a vine grown for its fruit. It can be either harvested young to be consumed ...

, both of which persisted in their new home. The medieval explorations, visits, and brief residence of the Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the ...

in Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, and Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

in the late 10th century and 11th century had no known impact on the Americas. Many scientists accept that possible contact between Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

and coastal peoples in South America around the year 1200 resulted in genetic similarities and the adoption by Polynesians of an American crop, the sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato ('' Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young ...

. However, it was only with the first voyage of the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

and his crew to the Americas in 1492

Year 1492 ( MCDXCII) was a leap year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

1492 is considered to be a significant year in the history of the West, Europe, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Spain, and the ...

that the Columbian exchange began, resulting in major transformations in the cultures and livelihoods of the peoples in both hemispheres.

Diseases

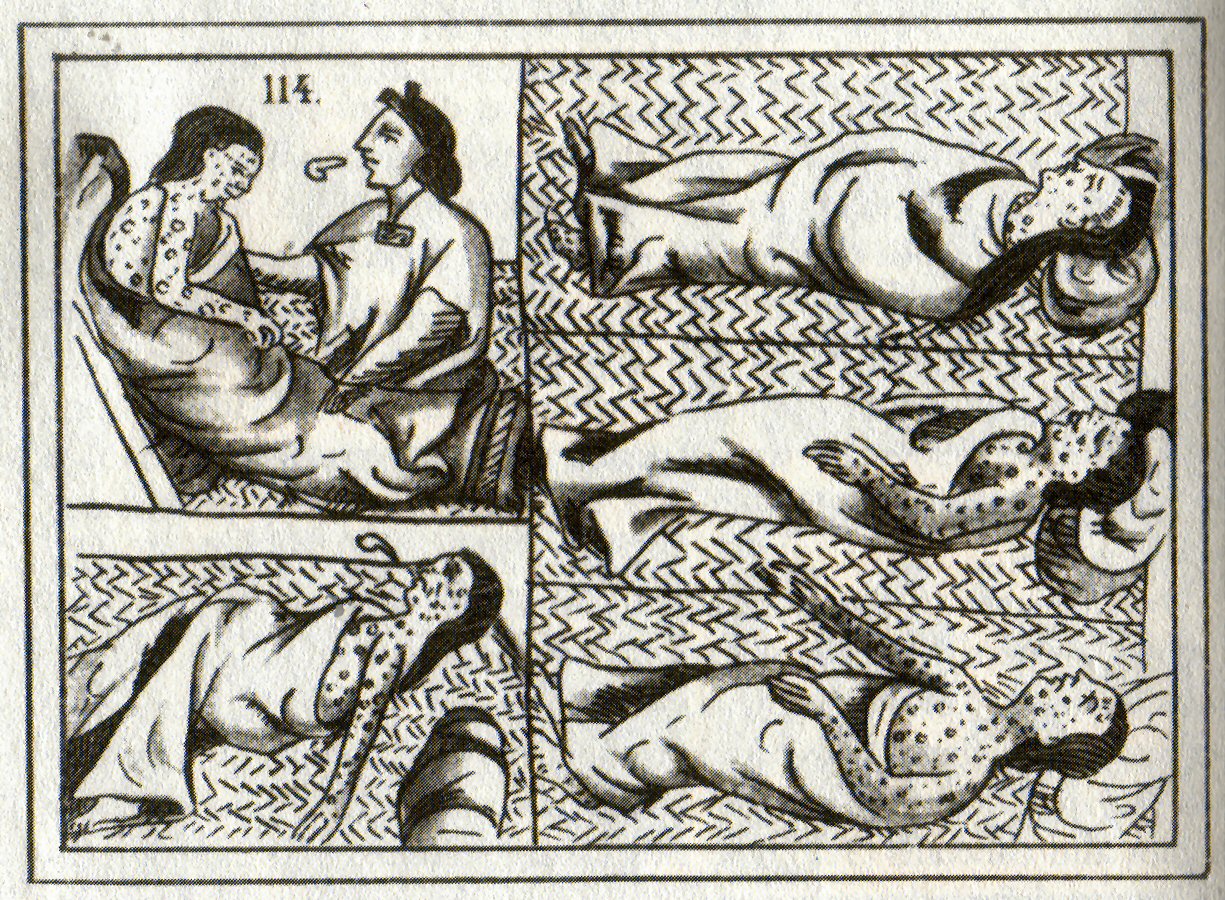

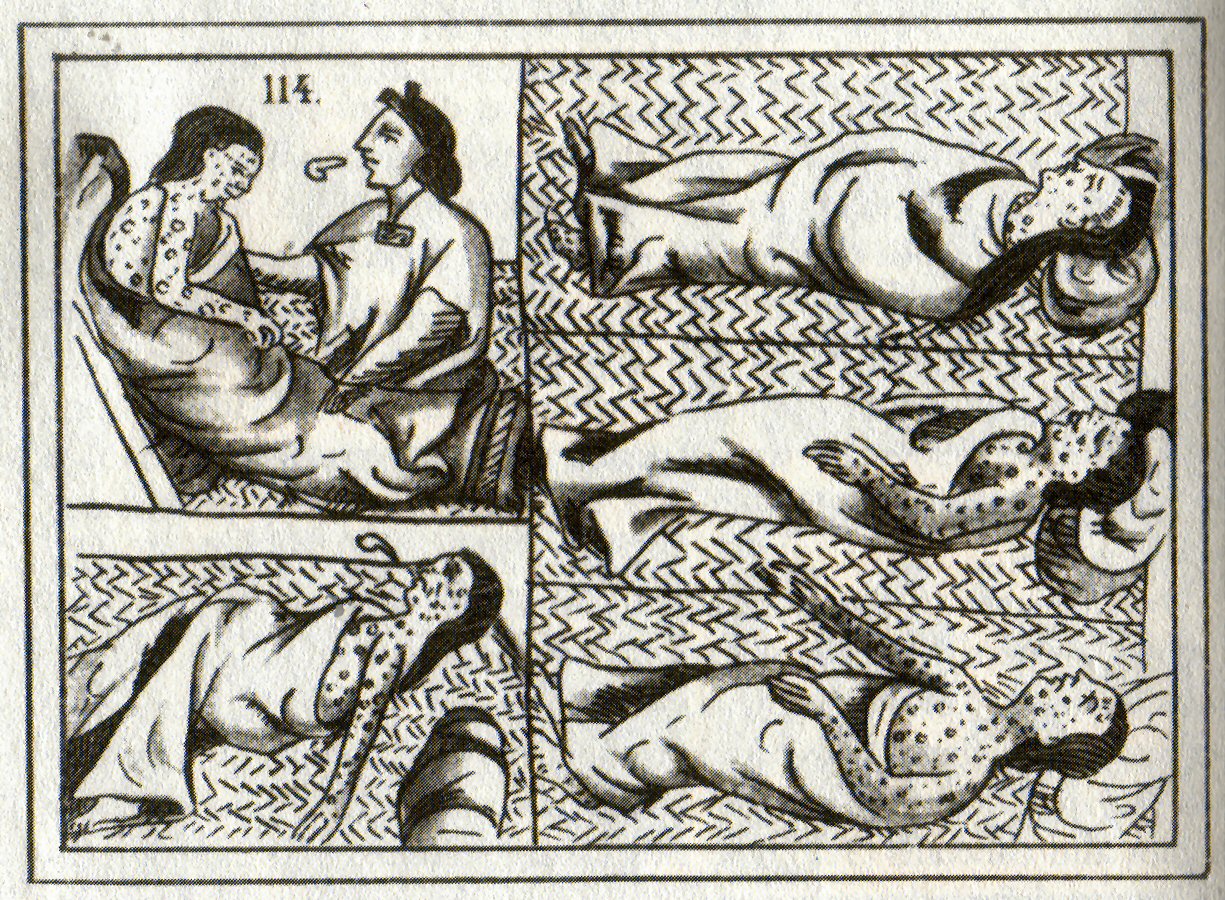

The first manifestation of the Columbian exchange may have been the spread of

The first manifestation of the Columbian exchange may have been the spread of syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

from the native people of the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexic ...

to Europe. The history of syphilis has been well-studied, but the origin of the disease remains a subject of debate. There are two primary hypotheses: one proposes that syphilis was carried to Europe from the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

by the crew of Christopher Columbus in the early 1490s, while the other proposes that syphilis previously existed in Europe but went unrecognized. The first written descriptions of the disease in the Old World came in 1493. The first large outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494–1495 among the army of Charles VIII during its invasion of Naples. Many of the crew members who had served with Columbus had joined this army. After the victory, Charles's largely mercenary army returned to their respective homes, thereby spreading "the Great Pox" across Europe and killing up to five million people.

The Columbian exchange of diseases in the other direction was by far deadlier. The peoples of the Americas had had no contact to European and African diseases and little or no immunity. An epidemic of swine influenza

Swine influenza is an infection caused by any of several types of swine influenza viruses. Swine influenza virus (SIV) or swine-origin influenza virus (S-OIV) refers to any strain of the influenza family of viruses that is endemic in pigs. As ...

beginning in 1493 killed many of the Taino people inhabiting Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

islands. The pre-contact population of the island of Hispanola was probably at least 500,000, but by 1526, fewer than 500 were still alive. Spanish exploitation was part of the cause of the near-extinction of the native people. In 1518, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

was first recorded in the Americas and became the deadliest imported European disease. Forty percent of the 200,000 people living in the Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

capital of Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

, later Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

, are estimated to have died of smallpox in 1520 during the war of the Aztecs with conquistador Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

. Epidemics, possibly of smallpox and spread from Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, decimated the population of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

a few years before the arrival of the Spanish. The ravages of European diseases and Spanish exploitation reduced the Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

population from an estimated 20 million to barely more than a million in the 16th century. The indigenous population of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

decreased from about 9 million in the pre-Columbian era to 600,000 in 1620. Scholars Nunn and Qian estimate that 80–95 percent of the Native American population died in epidemics within the first 100–150 years following 1492. The deadliest Old World diseases in the Americas were smallpox, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, whooping cough

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or t ...

, chicken pox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV). The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab ...

, bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

, typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

, and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

.

African slavery

The

The Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

consisted of the involuntary immigration of 11.7 million Africans, primarily from West Africa, to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries, far outnumbering the about 3.4 million Europeans who migrated, most voluntarily, to the New World between 1492 and 1840. The prevalence of African slaves in the New World was related to the demographic decline of New World peoples and the need of European colonists for labor. The Africans had greater immunities to Old World diseases than the New World peoples, and were less likely to die from disease. The journey of African slaves from Africa to America is commonly known as the "middle passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods (first ...

".

Enslaved Africans helped shape an emerging African-American culture in the New World. They participated in both skilled and unskilled labor. Their descendants gradually developed an ethnicity that drew from the numerous African tribes as well as European nationalities. The descendants of African slaves make up a majority of the population in some Caribbean countries, notably Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, and a sizeable minority in most American countries.

A movement for the abolition of slavery, known as abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, developed in Europe and the Americas during the 18th century. The efforts of abolitionists eventually led to the abolition of slavery (the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

in 1833

Events January–March

* January 3 – Reassertion of British sovereignty over the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic.

* February 6 – His Royal Highness Prince Otto Friedrich Ludwig of Bavaria assumes the title His Majesty Othon the ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in 1865

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The New York Stock Exchange opens its first permanent headquarters at 10-12 Broad near Wall Street, in New York City.

* January 13 – American Civil War : Second Battle of Fort Fisher ...

, and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

in 1888

In Germany, 1888 is known as the Year of the Three Emperors. Currently, it is the year that, when written in Roman numerals, has the most digits (13). The next year that also has 13 digits is the year 2388. The record will be surpassed as late ...

).

Silver

The New World produced 80 percent or more of the world'ssilver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

in the 16th and 17th centuries, most of it at Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

in Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, but also in Mexico. The founding of the city of Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

in 1571 for the purpose of facilitating trade in New World silver with China for silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

, porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

, and other luxury products has been called by scholars the "origin of world trade." China was the world's largest economy and in the 1570s adopted silver (which it did not produce in any quantity) as its medium of exchange. China had little interest in buying foreign products so trade consisted of large quantities of silver coming into China to pay for the Chinese products that foreign countries desired. Silver made it to Manila either through Europe and by ship around the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

or across the Pacific Ocean in Spanish galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch ...

s from the Mexican port of Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , also , nah, Acapolco), is a city and major seaport in the state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Acapulco is located on a deep, semicircular bay and has ...

. From Manila the silver was transported onward to China on Portuguese and later Dutch ships. Silver was also smuggled from Potosi to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

to pay slavers for African slaves imported into the New World.

The enormous quantities of silver imported into Spain and China created vast wealth but also caused inflation and the value of silver to decline. In 16th century China, six ounces of silver was equal to the value of one ounce of gold. In 1635, it took 13 ounces of silver to equal in value one ounce of gold. Taxes in both countries were assessed in the weight of silver, not its value. The shortage of revenue due to the decline in the value of silver may have contributed indirectly to the fall of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

in 1644. Likewise, silver from the Americas financed Spain's attempt to conquer other countries in Europe, and the decline in the value of silver left Spain faltering in the maintenance of its world-wide empire and retreating from its aggressive policies in Europe after 1650.

The wheel

Although large-scale use of wheels did not occur in the Americas prior to European contact, numerous small wheeled artifacts, identified as children's toys, have been found in Mexican archeological sites, some dating to approximately 1500 BCE. Some argue that the primary obstacle to large-scale development of the wheel in the Americas was the absence of domesticated large animals that could be used to pull wheeled carriages. The closest relative of

Although large-scale use of wheels did not occur in the Americas prior to European contact, numerous small wheeled artifacts, identified as children's toys, have been found in Mexican archeological sites, some dating to approximately 1500 BCE. Some argue that the primary obstacle to large-scale development of the wheel in the Americas was the absence of domesticated large animals that could be used to pull wheeled carriages. The closest relative of cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

present in Americas in pre-Columbian times, the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the ...

, is difficult to domesticate and was never domesticated by Native Americans; several horse species existed until about 12,000 years ago, but ultimately became extinct. The only large animal that was domesticated in the Western hemisphere, the llama

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is soft ...

, a pack animal, was not physically suited to use as a draft animal to pull wheeled vehicles, and use of the llama did not spread far beyond the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

by the time of the arrival of Europeans.

On the other hand, Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

ns never developed the wheelbarrow

A wheelbarrow is a small hand-propelled vehicle, usually with just one wheel, designed to be pushed and guided by a single person using two handles at the rear, or by a sail to push the ancient wheelbarrow by wind. The term "wheelbarrow" is ma ...

, the potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, ...

, nor any other practical object with a wheel or wheels. Although present in a number of toys, very similar to those found throughout the world and still made for children today ("pull toys"), the wheel was never put into practical use in Mesoamerica before the 16th century. Possibly the closest New World civilizations came to the utilitarian wheel is the spindle whorl

A spindle whorl is a disc or spherical object fitted onto the spindle to increase and maintain the speed of the spin. Historically, whorls have been made of materials like amber, antler, bone, ceramic, coral, glass, stone, metal (iron, lead, lea ...

, and some scholars believe that the Mayan toys were originally made with spindle whorls and spindle sticks as "wheels" and "axes".

Effects

Crops

Because of the new trading resulting from the Columbian exchange, several plants native to the Americas have spread around the world, includingpotatoes

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern United ...

, maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

, tomatoes, and tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

. Before 1500, potatoes were not grown outside of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. By the 18th century, they were cultivated and consumed widely in Europe and had become important crops in both India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and North America. Potatoes eventually became an important staple of the diet in much of Europe, contributing to an estimated 25% of the population growth in Afro-Eurasia between 1700 and 1900. Many European rulers, including Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

of Prussia and Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

of Russia, encouraged the cultivation of the potato.

Maize and cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

, introduced by the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

from South America in the 16th century, gradually replaced sorghum

''Sorghum'' () is a genus of about 25 species of flowering plants in the grass family (Poaceae). Some of these species are grown as cereals for human consumption and some in pastures for animals. One species is grown for grain, while many other ...

and millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets a ...

as Africa's most important food crops. Spanish colonizers of the 16th-century introduced new staple crops to Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

from the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

, including maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

and sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato ('' Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young ...

es, and thereby contributed to population growth in Asia. On a larger scale, the introduction of potatoes and maize to the Old World "resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples" throughout the Eurasian landmass, enabling more varied and abundant food production.

Tomatoes, which came to Europe from the New World via Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, were initially prized in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

mainly for their ornamental value. But starting in the 19th century, tomato sauce

Tomato sauce (also known as ''salsa roja'' in Spanish or ''salsa di pomodoro'' in Italian) can refer to many different sauces made primarily from tomatoes, usually to be served as part of a dish, rather than as a condiment. Tomato sauces are ...

s became typical of Neapolitan cuisine

Neapolitan cuisine has ancient historical roots that date back to the Greco-Roman period, which was enriched over the centuries by the influence of the different cultures that controlled Naples and its kingdoms, such as that of Aragon and France ...

and, ultimately, Italian cuisine

Italian cuisine (, ) is a Mediterranean cuisine#CITEREFDavid1988, David 1988, Introduction, pp.101–103 consisting of the ingredients, recipes and List of cooking techniques, cooking techniques developed across the Italian Peninsula and late ...

in general. Coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

Seeds of ...

(introduced in the Americas circa 1720) from Africa and the Middle East and sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

(introduced from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

) from the Spanish West Indies

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The Indies was the d ...

became the main export commodity crops of extensive Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

n plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

. Introduced to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

by the Portuguese, chili and potatoes from South America have become an integral part of their cuisine.

Because crops traveled but often their endemic fungi did not, for a limited time yields were higher in their new lands. Dark & Gent 2001 term this the "". However, as globalization has continued the ''Columbian Exchange of pathogens'' has continued and crops have declined back toward their endemic yields the honeymoon is ending.

Rice

Rice was another crop that became widely cultivated during the Columbian exchange. As the demand in the New World grew, so did the knowledge of how to cultivate it. The two primary species used were ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown in West Africa around 3,000 years ago. In agriculture, it has largely been replaced by higher-yielding Asian ...

'' and ''Oryza sativa

''Oryza sativa'', commonly known as Asian rice or indica rice, is the plant species most commonly referred to in English as ''rice''. It is the type of farmed rice whose cultivars are most common globally, and was first domesticated in the Yan ...

'', originating from West Africa and Southeast Asia, respectively. European planters in the New World relied upon the skills of African slaves to cultivate both species. Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

were major centers of rice production during the colonial era. Enslaved Africans brought their knowledge of water control, milling, winnowing, and other agrarian practices to the fields. This widespread knowledge among African slaves eventually led to rice becoming a staple dietary item in the New World.

Fruits

Citrus fruits and grapes were brought to the Americas from the Mediterranean. At first planters struggled to adapt these crops to the climates in the New World, but by the late 19th century they were cultivated more consistently. Bananas were introduced into the Americas in the 16th century by Portuguese sailors who came across the fruits in West Africa, while engaged in commercial ventures and the slave trade. Bananas were consumed in minimal amounts in the Americas as late as the 1880s. The U.S. did not see major increases in banana consumption until large plantations were established in the Caribbean.Tomatoes

It took three centuries after their introduction in Europe for tomatoes to become a widely accepted food item. Tobacco, potatoes,chili peppers

Chili peppers (also chile, chile pepper, chilli pepper, or chilli), from Nahuatl '' chīlli'' (), are varieties of the berry-fruit of plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for t ...

, tomatillos, and tomatoes are all members of the nightshade family. Similar to some European nightshade varieties, tomatoes and potatoes can be harmful or even lethal if the wrong part of the plant is consumed in excess. Physicians in the 16th century had good reason to suspect that this native Mexican fruit was poisonous; they suspected it of generating "melancholic humours".

In 1544, Pietro Andrea Mattioli

Pietro Andrea Gregorio Mattioli (; 12 March 1501 – ) was a doctor and naturalist born in Siena.

Biography

He received his MD at the University of Padua in 1523, and subsequently practiced the profession in Siena, Rome, Trento and Gorizia ...

, a Tuscan physician and botanist, suggested that tomatoes might be edible, but no record exists of anyone consuming them at this time. However, in 1592 the head gardener at the botanical garden of Aranjuez

Aranjuez () is a city and municipality of Spain, part of the Community of Madrid.

Located in the southern end of the region, the main urban nucleus lies on the left bank of Tagus, a bit upstream the discharge of the Jarama. , the municipality h ...

near Madrid, under the patronage of Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, wrote, "it is said omatoesare good for sauces". In spite of these comments, tomatoes remained exotic plants grown for ornamental purposes, but rarely for culinary use. On October 31, 1548, the tomato was given its first name anywhere in Europe when a house steward of Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence, wrote to the De' Medici's private secretary that the basket of ''pomi d'oro'' "had arrived safely". At this time, the label ''pomi d'oro'' was also used to refer to figs, melons, and citrus fruits in treatises by scientists.''A History of the Tomato in Italy Pomodoro!'', David Gentilcore (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010). In the early years, tomatoes were mainly grown as ornamentals in Italy. For example, the Florentine aristocrat Giovan Vettorio Soderini wrote that they "were to be sought only for their beauty" and were grown only in gardens or flower beds. Tomatoes were grown in elite town and country gardens in the fifty years or so following their arrival in Europe, and were only occasionally depicted in works of art. The practice of using tomato sauce

Tomato sauce (also known as ''salsa roja'' in Spanish or ''salsa di pomodoro'' in Italian) can refer to many different sauces made primarily from tomatoes, usually to be served as part of a dish, rather than as a condiment. Tomato sauces are ...

with pasta developed only in the late nineteenth century. Today around of tomatoes are cultivated in Italy.

Livestock

Initially at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals.

Initially at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals. Horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s, donkeys

The domestic donkey is a hoofed mammal in the family Equidae, the same family as the horse. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a ...

, mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two po ...

s, pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

, cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

, sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticate ...

, goats

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of th ...

, chickens

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domestication, domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey junglefowl, grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster ...

, large dogs

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it is derived from the extinct Pleistocene wolf, and the modern wolf is the dog's nearest living relative. ...

, cats

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members o ...

, and bees

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyletic lineage within the superfam ...

were rapidly adopted by native peoples for transport, food, and other uses. One of the first European exports to the Americas, the horse, changed the lives of many Native American tribes. The mountain tribes shifted to a nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

lifestyle, based on hunting bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

on horseback. They largely gave up settled agriculture. Horse culture was adopted gradually by Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

Indians. The existing Plains tribes expanded their territories with horses, and the animals were considered so valuable that horse herds became a measure of wealth. While mesoamerican peoples (Mayas in particular) already practiced apiculture

Beekeeping (or apiculture) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in man-made beehives. Honey bees in the genus '' Apis'' are the most-commonly-kept species but other honey-producing bees such as '' Melipona'' stingless bees are also kept. ...

, producing wax and honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

from a variety of bees (such as ''Melipona

''Melipona'' is a genus of stingless bees, widespread in warm areas of the Neotropics, from Sinaloa and Tamaulipas (México) to Tucumán and Misiones (Argentina). About 70 species are known.Grüter, C. 2020. ''Stingless Bees: Their Behaviour, E ...

'' or ''Trigona

''Trigona'' is one of the largest genera of stingless bees, comprising about 32 species, exclusively occurring in the New World, and formerly including many more subgenera than the present assemblage; many of these former subgenera have been el ...

''), European bees (''Apis mellifera

The western honey bee or European honey bee (''Apis mellifera'') is the most common of the 7–12 species of honey bees worldwide. The genus name ''Apis'' is Latin for "bee", and ''mellifera'' is the Latin for "honey-bearing" or "honey carrying", ...

'')—more productive, delivering a honey with less water content and allowing for an easier extraction from beehives—were introduced in New Spain, becoming an important part of farming production.

The effects of the introduction of European livestock on the environments and peoples of the New World were not always positive. In the Caribbean, the proliferation of European animals consumed native fauna and undergrowth, changing habitat. If free ranging, the animals often damaged ''conucos,'' plots managed by indigenous peoples for subsistence.

The Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who s ...

of Araucanía were fast to adopt the horse from the Spanish, and improve their military capabilities as they fought the Arauco War

The Arauco War was a long-running conflict between colonial Spaniards and the Mapuche people, mostly fought in the Araucanía. The conflict began at first as a reaction to the Spanish conquerors attempting to establish cities and force Mapuche ...

against Spanish colonizers. Until the arrival of the Spanish, the Mapuches had largely maintained chilihueques (llamas

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is s ...

) as livestock. The Spanish introduction of sheep caused some competition between the two domesticated species. Anecdotal evidence of the mid-17th century show that by then both species coexisted but that the sheep far outnumbered the llamas. The decline of llamas reached a point in the late 18th century when only the Mapuche from Mariquina and Huequén next to Angol

Angol is a commune and capital city of the Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of southern Chile. It is located at the foot of the Nahuelbuta Range and next to the Vergara River, that permitted communications by small boats to the Bío- ...

raised the animal. In the Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

the introduction of pigs by the Spanish proved a success. They could feed on the abundant shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater environ ...

and algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

exposed by the large tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s.

In the other direction, the turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus '' Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ...

, and Muscovy duck were New World animals that were transferred to Europe.

Medicines

European exploration of tropical areas was aided by the New World discovery ofquinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, the first effective treatment for malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

. Europeans suffered from this disease, but some indigenous populations had developed at least partial resistance to it. In Africa, resistance to malaria has been associated with other genetic changes among sub-Saharan Africans and their descendants, which can cause sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red ...

. The resistance of sub-Saharan Africans to malaria in the southern United States and the Caribbean contributed greatly to the specific character of the Africa-sourced slavery in those regions.

Similarly, yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

is thought to have been brought to the Americas from Africa via the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

. Because it was endemic in Africa, many people there had acquired immunity. Europeans suffered higher rates of death than did African-descended persons when exposed to yellow fever in Africa and the Americas, where numerous epidemics swept the colonies beginning in the 17th century and continuing into the late 19th century. The disease caused widespread fatalities in the Caribbean during the heyday of slave-based sugar plantation. The replacement of native forests by sugar plantations and factories facilitated its spread in the tropical area by reducing the number of potential natural mosquito predators.The means of yellow fever transmission was unknown until 1881, when Carlos Finlay

Carlos Juan Finlay (December 3, 1833 – August 20, 1915) was a Cuban epidemiologist recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it was transmitted through mosquitoes ''Aedes aegypti''.

Biography

Early life and ...

suggested that the disease was transmitted through mosquitoes, now known to be female mosquitoes of the species ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its l ...

''.

Cultural exchanges

One of the results of the movement of people between New and Old Worlds were cultural exchanges. For example, in the article "The Myth of Early Globalization: The Atlantic Economy, 1500–1800", Pieter Emmer makes the point that "from 1500 onward, a 'clash of cultures' had begun in the Atlantic". This clash of culture involved the transfer of European values to indigenous cultures. As an example, the emergence of the concept ofprivate property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

in regions where property was often viewed as communal, concepts of monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., pol ...

(although many indigenous peoples were already monogamous), the role of women and children in the social system, and different concepts of labor, including slavery, although slavery was already a practice among many indigenous peoples and was widely practiced or introduced by Europeans into the Americas. Another example included the European abhorrence of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

, a religious practice among some indigenous populations.

During the initial stages of European colonization of the Americas, Europeans encountered fence-less lands. They believed that the land was unimproved and available for their taking, as they sought economic opportunity and homesteads. However, when European settlers arrived in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, they encountered a fully established indigenous people, the Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

. The Powhatan farmers in Virginia scattered their farm plots within larger cleared areas. These larger cleared areas were a communal place for growing useful plants. As the Europeans viewed fences as hallmarks of civilization, they set about transforming "the land into something more suitable for themselves".

Tobacco was a New World agricultural product, originally a luxury good spread as part of the Columbian exchange. As is discussed in regard to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the tobacco trade increased demand for free labor and spread tobacco worldwide. In discussing the widespread uses of tobacco, the Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes (1493–1588) noted that "The black people that have gone from these parts to the Indies, have taken up the same manner and use of tobacco that the Indians have". As Europeans traveled to other parts of the world, they took with them the practices related to tobacco. Demand for tobacco grew in the course of these cultural exchanges among peoples.

One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of

One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, steeped in a European values system, was a major objective of colonization. Europeans often pursued it via explicit policies of suppression of indigenous languages, cultures and religions. In British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas fro ...

, Protestant missionaries converted many members of indigenous tribes to Protestantism. The French colonies had a more outright religious mandate, as some of the early explorers, such as Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

, were also Catholic priests. In time, and given the European technological and immunological superiority which aided and secured their dominance, indigenous religions declined in the centuries following the European settlement of the Americas.

While Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who s ...

people did adopt the horse, sheep, and wheat, the over-all scant adoption of Spanish technology by Mapuche has been characterized as a means of cultural resistance.

According to Caroline Dodds Pennock, in Atlantic history

Atlantic history is a specialty field in history that studies the Atlantic World in the early modern period. The Atlantic World was created by the discovery of a new land by Europeans, and Atlantic History is the study of that world. It is p ...

indigenous people are often seen as static recipients of transatlantic encounters. But thousands of Native Americans crossed the ocean during the sixteenth century, some by choice.

Organism examples

Later history

Plants that arrived by land, sea, or air in the times before 1492 are calledarchaeophyte

An archaeophyte is a plant species which is non-native to a geographical region, but which was an introduced species in "ancient" times, rather than being a modern introduction. Those arriving after are called neophytes.

The cut-off date is u ...

s, and plants introduced to Europe after those times are called neophytes. Invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species adv ...

of plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s and pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

s also were introduced by chance, including such weeds as tumbleweeds

A tumbleweed is a kind of plant habit or structure.

Tumbleweed, tumble-weed or tumble weed may also refer to:

Films

* ''Tumbleweeds'' (1925 film), William S. Hart film

* ''Tumbling Tumbleweeds'' (1935 film), Gene Autry film

* ''Tumbleweed'' (1 ...

(''Salsola'' spp.) and wild oats (''Avena fatua''). Some plants introduced intentionally, such as the kudzu vine introduced in 1894 from Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

to the United States to help control soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

, have since been found to be invasive pests in the new environment.

Fungi have also been transported, such as the one responsible for Dutch elm disease

Dutch elm disease (DED) is caused by a member of the sac fungi (Ascomycota) affecting elm trees, and is spread by elm bark beetles. Although believed to be originally native to Asia, the disease was accidentally introduced into America, Europe ...

, killing American elms in North American forests and cities, where many had been planted as street trees. Some of the invasive species have become serious ecosystem and economic problems after establishing in the New World environments. A beneficial, although probably unintentional, introduction is ''Saccharomyces eubayanus

''Saccharomyces eubayanus'', a cryotolerant (cold tolerant) type of yeast, is most likely the parent of the lager brewing yeast, '' Saccharomyces pastorianus''..

Lager is a type of beer created from malted barley and fermented at low tempera ...

'', the yeast responsible for lager

Lager () is beer which has been brewed and conditioned at low temperature. Lagers can be pale, amber, or dark. Pale lager is the most widely consumed and commercially available style of beer. The term "lager" comes from the German for "storag ...

beer now thought to have originated in Patagonia