Terence V. Powderly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

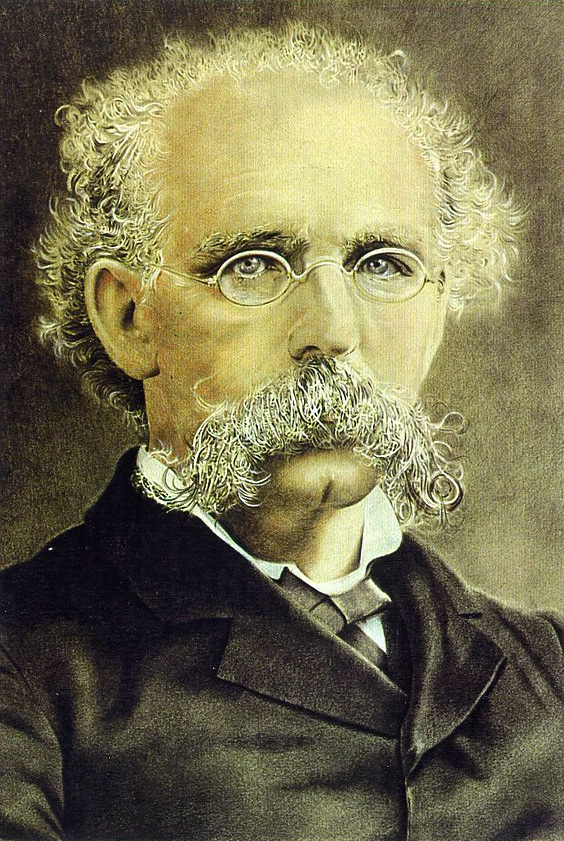

Terence Vincent Powderly (January 22, 1849 – June 24, 1924) was an

Powderly's insistence on ending both these strikes meant that the companies did not fear the K of L would use strikes as direct action to gain wage and labor benefits. After this, both Jay Gould and the Chicago Packinghouses won complete victories in breaking both strikes.

Disaster struck the Knights with the Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago on May 4, 1886. Anarchists were blamed, and two of them were Knights. Membership plunged overnight as a result of false rumors linking the Knights to anarchism and terrorism. However the disorganization of the group and its record of losing strike after strike disillusioned many members. Bitter factionalism divided the union, and its forays into electoral politics were failures because Powderly forbade its members to engage in political activity or to field candidates

Many KoL members joined more conservative alternatives, especially the Railroad brotherhoods, and the unions affiliated with the

Powderly's insistence on ending both these strikes meant that the companies did not fear the K of L would use strikes as direct action to gain wage and labor benefits. After this, both Jay Gould and the Chicago Packinghouses won complete victories in breaking both strikes.

Disaster struck the Knights with the Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago on May 4, 1886. Anarchists were blamed, and two of them were Knights. Membership plunged overnight as a result of false rumors linking the Knights to anarchism and terrorism. However the disorganization of the group and its record of losing strike after strike disillusioned many members. Bitter factionalism divided the union, and its forays into electoral politics were failures because Powderly forbade its members to engage in political activity or to field candidates

Many KoL members joined more conservative alternatives, especially the Railroad brotherhoods, and the unions affiliated with the

President

President

"The Organization of Labor,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 135, no. 2, whole no. 309 (August 1882), pp. 118–127.

"The Army of the Discontented,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 140, whole no. 341 (April 1885), pp. 369–378.

"A Menacing Irruption,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 147, whole no. 381 (August 1888), pp. 369–378.

"The Plea for Eight Hours,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 150, whole no. 401 (April 1890), pp. 464–470.

"The Workingman and Free Silver,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 153, whole no. 421 (December 1891), pp. 728–737.

''Thirty Years of Labor, 1859-1889.''

Columbus, OH: Excelsior Publishing House 1890. * "Government Ownership of Railways," ''The Arena,'' vol. 7, whole no. 37 (December 1892), pp. 58–63. * ''The Path I Trod: The Autobiography of Terence V. Powderly.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

in JSTOR

* Falzone, Vincent J. ''Terence V. Powderly: Middle Class Reformer.'' Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1978. * Falzone, Vincent J. "Terence V. Powderly: Politician and Progressive Mayor of Scranton, 1878-1884," ''Pennsylvania History,'' vol. 41 (1974), pp. 289–310. * McNeill, George E. (ed.)

''The Labor Movement: The Problem of To-day.''

New York: M.W. Hazen Co., 1889. * Oestreicher, Richard. "Terence Powderly, the Knights of Labor, and artisanal republicanism." in ''Labor Leaders in America'' (1987): 30-61

online

* Phelan, Craig. ''Grand Master Workman: Terence Powderly and the Knights of Labor'' (Greenwood, 2000), scholarly biograph

online

* Voss, Kim. ''The Making of American Exceptionalism: The Knights of Labor and Class Formation in the Nineteenth Century.'' (Cornell University Press, 1994). * Walker, Samuel. "Terence V. Powderly, Machinist: 1866-1877," ''Labor History,'' vol. 19 (1978), pp. 165–184. * Ware, Norman J. ''The Labor Movement in the United States, 1860 - (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996

online edition

* Weir, Robert E. ''Knights Unhorsed: Internal Conflict in Gilded Age Social Movement'' (Wayne State University Press, 2000) * Wright, Carroll D. "An Historical Sketch of the Knights of Labor," ''Quarterly Journal of Economics,'' vol. 1, no. 2 (January 1887), pp. 137–168

in JSTOR

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

labor union leader, politician and attorney, best known as head of the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

in the late 1880s. Born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania

Carbondale is a city in Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carbondale is located approximately 15 miles due northeast of the city of Scranton in Northeastern Pennsylvania. The population was 8,828 at the 2020 census.

The land area th ...

, he was later elected mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming V ...

, for three 2-year terms, starting in 1878. A Republican, he served as the United States Commissioner General of Immigration in 1897. The Knights of Labor was one of the largest white American labor organizations of the 19th century, but Powderly was a poor administrator and could barely keep it under control. His small central office could not supervise or coordinate the many strikes and other activities sponsored by union locals. Powderly believed that the Knights was an educational tool to uplift the white workingman, and he downplayed the use of strikes to achieve workers' goals.

His influence reportedly led to the passing of the alien contract labor law The 1885 Alien Contract Labor Law (Sess. II Chap. 164; 23 Stat. 332), also known as the Foran Act, was an act to prohibit the importation and migration of foreigners and aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor in the United States, its ...

in 1885 and establishment of labor bureaus and arbitration boards in many states. The Knights failed to maintain its large membership after being blamed for the violence of the Haymarket Riot

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in ...

of 1886. It was increasingly upstaged by the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

under Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, which coordinated numerous specialized craft unions that appealed to skilled workers, instead of the mix of unskilled, semiskilled, and skilled workers in the Knights.

Early life

Powderly was born the 11th of 12 children on January 22, 1849 toIrish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

parents who had come up from poverty, Terence Powderly and Madge Walsh, who had emigrated to the United States in 1827. As a child he contracted the measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, as well as scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by '' Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects chi ...

which left him deaf

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is written ...

in one ear.

At 13 he began work for the railroad as a switchman

A switchman (North America) or pointsman (British Isles) is a rail transport worker whose original job was to operate various railway switches or points on a railroad. It also refers to a person who assists in moving cars in a railway yard o ...

with the Delaware and Hudson Railway

The Delaware and Hudson Railway (D&H) is a railroad that operates in the Northeastern United States. In 1991, after more than 150 years as an independent railroad, the D&H was purchased by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP). CP operates D&H ...

, before becoming a car examiner, repairer and eventually a brakeman

A brakeman is a rail transport worker whose original job was to assist the braking of a train by applying brakes on individual wagons. The earliest known use of the term to describe this occupation occurred in 1833. The advent of through brakes, ...

. On August 1, 1866, at the age of 17, he entered into an apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

as a machinist

A machinist is a tradesperson or trained professional who not only operates machine tools, but also has the knowledge of tooling and materials required to create set ups on machine tools such as milling machines, grinders, lathes, and drilling ...

with the local master mechanic, James Dickson, at which he was employed until August 15, 1869. Dickson himself had apprenticed to George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the ...

.

On November 21, 1871 Powderly joined the Subordinate Union No. 2 of Pennsylvania, part of the Machinists and Blacksmiths International Union, and a year later was elected as its secretary, before eventually becoming president. On September 19, 1872, Powderly married Hannah Dever.

Following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, Powderly was dismissed from this position at the railroad. In recalling the conversation, Powderly wrote that the master mechanic he worked for had explained to him, "You are the president of the union and it is thought best to dismiss you in order to head off trouble." He then spent the following winter in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

working odd jobs. He returned to the US in 1874, working briefly in Galion, Ohio

Galion is a city in Crawford, Morrow, and Richland counties in the U.S. state of Ohio. The population was 10,453 at the 2020 census. Galion is the second-largest city in Crawford County after Bucyrus.

The Crawford County portion of Galion i ...

before moving on to Oil City, Pennsylvania

Oil City is a city in Venango County, Pennsylvania known for its prominence in the initial exploration and development of the petroleum industry. It is located at a bend in the Allegheny River at the mouth of Oil Creek (Allegheny River tributary) ...

for six months, where he joined Pennsylvania Union No. 6. In August of that year, he was elected by No. 6 as a delegate to a district meeting representing Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Oil City, Meadville, and Franklin, and was in turn elected to represent the district at the general convention in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

in September.

Scranton

Powderly ended his travels in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he found work as a machinist installingcoal breaker

A coal breaker is a coal processing plant which breaks coal into various useful sizes. Coal breakers also remove impurities from the coal (typically slate) and deposit them into a culm dump. The coal breaker is a forerunner of the modern coal pre ...

s. Two weeks after taking the position, he was dismissed after being identified by the same man who had been instrumental in his previous dismissal in 1872. In response, he appealed to William Walker Scranton

William Walker Scranton (April 4, 1844 – December 3, 1916) was an American businessman based in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He became president and manager of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company after his father's death in 1872. The company ...

, who had given him the position to start. After explaining to Scranton that he had been fired originally due to his connection to the union, Powderly recalled:

He asked me if I was president then, I answered in the negative, but in order to be fully understood told him that I was at the time secretary. His next question was "If I reinstate you will you resign from the union?" My answer to that was: "I am insured for one thousand dollars in the union. I cannot afford any other insurance. If I resign and am killed in the employ of this company, will it pay my wife one thousand dollars?" He looked steadily at me a while and said: "Go to the mill and tell Davidson to set you to work."Through W. W. Scranton, Powderly went on to work for the

Dickson Manufacturing Company

Dickson Manufacturing Company was an American manufacturer of boilers, blast furnaces and steam engines used in various industries but most known in railway steam locomotives. The company also designed and constructed steam powered mine cable ho ...

, a firm founded by the sons of his apprentice master. He was again dismissed through the involvement of the same individual, and was again reinstated by Scranton, now in charge of the department, where he worked until May 31, 1877, when it closed for lack of work.

In 1878 following strikes and unrest in 1877, Powderly was elected to the first of three two-year terms as mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming V ...

, representing the Greenback-Labor Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

. During the election he proposed financing public works project through low interest government loans as a means of providing work for the many unemployed. After assuming office, he immediately reorganized the labor force and enacted moderate reforms.

Knights of Labor

Powderly is most remembered for leading theKnights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

("K of L"), a nationwide labor union. He joined the Knights in 1874, became Secretary of a District Assembly in 1877. He was elected Grand Master Workman in 1879 after the resignation of Uriah Smith Stephens

Uriah Smith Stephens (August 3, 1821 – February 13, 1882) was an American labor leader. He was most notable for his leadership of nine Philadelphia garment workers in founding the Knights of Labor in 1869, a successful early American labor unio ...

. At the time the Knights had around 10,000 members. He served as Grand Master Workman until 1893.

Powderly, along with most white labor leaders at the time, opposed the immigration of Chinese workers to the United States. He argued that non- European immigrants took jobs away from native-born Americans and drove down wages. He urged West Coast branches of the Knights of Labor to campaign for the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

. In speaking on nationwide violence against the "Chinese evil", Powderly blamed the "indifference of our law-makers to the just demands of the people for relief."

Powderly worked with Bishop James Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth ...

of to persuade the Pope to remove sanctions against Catholics who joined unions. The Catholic Church had opposed the unions as too influenced by rituals of freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. The Knights of Labor removed the words "The Holy and Noble Order of" from the name of the Knights of Labor in 1882 and abandoned any membership rituals associated with freemasonry.

Powderly was more influenced by the Greenback ideology of producerism

Producerism is an ideology which holds that those members of society engaged in the production of tangible wealth are of greater benefit to society than, for example, aristocrats who inherit their wealth and status.

History

Robert Ascher traces ...

than by socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

, a rising school of thought in Europe and the United States. Since producerism regarded most employers as "producers", Powderly disliked strikes. At times, the Knights organized strikes against local firms where the employer might be admitted as a member. The strikes would drive away the employers, resulting in a more purely working-class organization.

Despite his personal ambivalence about labor action, Powderly was skillful in organizing. The success of the Great Southwest railroad strike of 1886 against Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

's railroad more than compensated for the internal tension of his organization. The Knights of Labor grew so rapidly that at one point the organization called a moratorium on the issuance of charters.

The union was recognized as the first successful national labor union in the United States. In 1885-86 the Knights achieved their greatest influence and greatest membership. Powderly attempted to focus the union on cooperative endeavors and the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

. Soon the demands placed on the union by its members for immediate improvements, and the pressures of hostile business and government institutions, forced the Knights to function like a traditional labor union. However, the Knights were too disorganized to deal with the centralized industries that they were striking against. Powderly forbade them to use their most effective tool: the strike. Powderly intervened in two labor actions: the first against the Texas and Pacific Railroad in 1886 and the second against the Chicago Meatpackinghouse industry. 25,000 workers in the Union Stockyards struck for an 8-hour day in 1886 and to rescind a wage reduction. In both cases, Powderly ended strikes that historians believe that labor could have won. This is when the Knights of Labor began to lose its influence. Powderly also feared losing the support of the Catholic Church, which many immigrant workers belonged to; the church authorities were essentially conservative and feared that the K of L was plotting a "socialist revolution".

Powderly's insistence on ending both these strikes meant that the companies did not fear the K of L would use strikes as direct action to gain wage and labor benefits. After this, both Jay Gould and the Chicago Packinghouses won complete victories in breaking both strikes.

Disaster struck the Knights with the Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago on May 4, 1886. Anarchists were blamed, and two of them were Knights. Membership plunged overnight as a result of false rumors linking the Knights to anarchism and terrorism. However the disorganization of the group and its record of losing strike after strike disillusioned many members. Bitter factionalism divided the union, and its forays into electoral politics were failures because Powderly forbade its members to engage in political activity or to field candidates

Many KoL members joined more conservative alternatives, especially the Railroad brotherhoods, and the unions affiliated with the

Powderly's insistence on ending both these strikes meant that the companies did not fear the K of L would use strikes as direct action to gain wage and labor benefits. After this, both Jay Gould and the Chicago Packinghouses won complete victories in breaking both strikes.

Disaster struck the Knights with the Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago on May 4, 1886. Anarchists were blamed, and two of them were Knights. Membership plunged overnight as a result of false rumors linking the Knights to anarchism and terrorism. However the disorganization of the group and its record of losing strike after strike disillusioned many members. Bitter factionalism divided the union, and its forays into electoral politics were failures because Powderly forbade its members to engage in political activity or to field candidates

Many KoL members joined more conservative alternatives, especially the Railroad brotherhoods, and the unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

(AFL), which promoted craft unionism

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

over the one all-inclusive union concept. Powderly was defeated for re-election as Master Workman in 1893. As the decline of the Knights continued, Powderly moved on, opening a successful law practice in 1894.

Powderly was also a supporter of Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

's popular "single tax" on land values.

Later career

President

President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

appointed Powderly as the Commissioner General of Immigration where he served from July 1, 1897 to June 24, 1902. In this role he established a commission to investigate conditions at Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mil ...

, which ultimately led to 11 employees being dismissed. After being removed from the post in 1902 by Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, he continued to serve as Special Immigration Inspector, studying the causes of European emigration to the United States, where he recommended that officials inspect potential immigrants prior to their arrival in the US, station officers on immigrant-carrying ships, and take steps to more evenly distribute arriving immigrant populations geographically across the country.

Powderly was appointed as the chief of the newly created Immigration Service's Division of Information, with a mission, following his own prior recommendation, to "promote a beneficial distribution of aliens admitted into the United States." Finally, in 1921, three years prior to his death, he was appointed as a member of the Immigration Service's Board of Review.

Death

Powderly, a resident of thePetworth

Petworth is a small town and civil parish in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England. It is located at the junction of the A272 east–west road from Heathfield to Winchester and the A283 Milford to Shoreham-by-Sea road. Some twe ...

neighborhood in Washington, D.C., in the last years of his life, died at his home there on June 24, 1924. He is buried at nearby Rock Creek Cemetery

Rock Creek Cemetery is an cemetery with a natural and rolling landscape located at Rock Creek Church Road, NW, and Webster Street, NW, off Hawaii Avenue, NE, in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, D.C., United States. It is across the stre ...

. A second autobiography by Powderly, ''The Path I Trod'', was published posthumously in 1940. Powderly's papers are available for use at more than a dozen research libraries across the United States. He was survived by his second wife, Emma (Fickensher), who was his late wife's cousin and a former work associate, who he had married in 1919.

Legacy

Powderly was inducted into theU.S. Department of Labor

The United States Department of Labor (DOL) is one of the United States federal executive departments, executive departments of the federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government. It is responsible for the administration of fede ...

Hall of Honor in 1999. The citation reads as follows:

As leader of the Knights of Labor, the nation's first successful trade union organization, Terence V. Powderly thrust the workers' needs to the fore for the first time in U.S. history. In the 1800s, far in advance for the period, he sought the inclusion of blacks, women and Hispanics for full-fledged membership in his trade union. With labor struggling for a place at America's economic table, Powderly achieved national stature as the recognized spokesman for the workers' interest and for the first time made organized labor a political force to be reckoned with.Writing in Dubofsky and Van Tine's ''Labor Leaders in America'', Richard Oestreicher described Powderly as "the first labor leader in American history to become a media superstar". Oestreicher continues:

No other worker in these years, not even his rival Samuel Gompers, captured as much attention from reporters, from politicians, or from industrialists. To his contemporaries Powderly ''was'' the Knights of Labor.Oestreicher characterizes Powderly's legacy as leader of the Knights as generally one of failure to preserve the organization and its mission through the labor upheavals of the late 19th Century. However, he continues to describe him as an "energetic and capable organizer," and is quick to point out the practical challenges both he and the Knights faced, and that in comparison to his heirs and contemporaries, "quite simply, no one else did much better han they didover the next forty years." In 1966 Powderly's long time home at 614 North Main Street in Scranton was designated by the

National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational properti ...

as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

. On November 18, 1947 a historical maker was placed in Scranton honoring Powderly.

Works

"The Organization of Labor,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 135, no. 2, whole no. 309 (August 1882), pp. 118–127.

"The Army of the Discontented,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 140, whole no. 341 (April 1885), pp. 369–378.

"A Menacing Irruption,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 147, whole no. 381 (August 1888), pp. 369–378.

"The Plea for Eight Hours,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 150, whole no. 401 (April 1890), pp. 464–470.

"The Workingman and Free Silver,"

''North American Review,'' vol. 153, whole no. 421 (December 1891), pp. 728–737.

''Thirty Years of Labor, 1859-1889.''

Columbus, OH: Excelsior Publishing House 1890. * "Government Ownership of Railways," ''The Arena,'' vol. 7, whole no. 37 (December 1892), pp. 58–63. * ''The Path I Trod: The Autobiography of Terence V. Powderly.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

* Carman, Harry J. "Terence Vincent Powderly -An Appraisal," ''Journal of Economic History'' Vol. 1, No. 1 (May, 1941), pp. 83–8in JSTOR

* Falzone, Vincent J. ''Terence V. Powderly: Middle Class Reformer.'' Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1978. * Falzone, Vincent J. "Terence V. Powderly: Politician and Progressive Mayor of Scranton, 1878-1884," ''Pennsylvania History,'' vol. 41 (1974), pp. 289–310. * McNeill, George E. (ed.)

''The Labor Movement: The Problem of To-day.''

New York: M.W. Hazen Co., 1889. * Oestreicher, Richard. "Terence Powderly, the Knights of Labor, and artisanal republicanism." in ''Labor Leaders in America'' (1987): 30-61

online

* Phelan, Craig. ''Grand Master Workman: Terence Powderly and the Knights of Labor'' (Greenwood, 2000), scholarly biograph

online

* Voss, Kim. ''The Making of American Exceptionalism: The Knights of Labor and Class Formation in the Nineteenth Century.'' (Cornell University Press, 1994). * Walker, Samuel. "Terence V. Powderly, Machinist: 1866-1877," ''Labor History,'' vol. 19 (1978), pp. 165–184. * Ware, Norman J. ''The Labor Movement in the United States, 1860 - (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996

online edition

* Weir, Robert E. ''Knights Unhorsed: Internal Conflict in Gilded Age Social Movement'' (Wayne State University Press, 2000) * Wright, Carroll D. "An Historical Sketch of the Knights of Labor," ''Quarterly Journal of Economics,'' vol. 1, no. 2 (January 1887), pp. 137–168

in JSTOR

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Powderly, Terence V. 1849 births 1924 deaths American lawyers American trade unionists of Irish descent Burials at Rock Creek Cemetery Catholics from Pennsylvania Georgists Knights of Labor people American trade union leaders Mayors of Scranton, Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Greenbacks People from Carbondale, Pennsylvania Trade unionists from Pennsylvania