Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

's tenure as the

34th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

began with

his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory over

Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Adlai Stevenson in the

1952 presidential election.

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

succeeded him after winning the

1960 presidential election.

Eisenhower held office during the

Cold War, a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Eisenhower's New Look policy stressed the importance of

nuclear weapons as a deterrent to military threats, and the United States built up a stockpile of

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s and

nuclear weapons delivery

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

''Strategic'' nuclear weapons are used primari ...

systems during Eisenhower's presidency. Soon after taking office, Eisenhower negotiated an end to the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, resulting in the partition of

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

. Following the

Suez Crisis, Eisenhower promulgated the

Eisenhower Doctrine

The Eisenhower Doctrine was a policy enunciated by Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 5, 1957, within a "Special Message to the Congress on the Situation in the Middle East". Under the Eisenhower Doctrine, a Middle Eastern country could request Ame ...

, strengthening U.S. commitments in the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

. In response to the

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

, the Eisenhower administration broke ties with

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles, eventually resulting in the failed

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

. Eisenhower also allowed the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

to engage in covert actions, such as the

1953 Iranian coup d'état

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup d'état ( fa, کودتای ۲۸ مرداد), was the overthrow of the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in favor of strengthening the monarchical rule of ...

and the

1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état was the result of a CIA covert operation code-named PBSuccess. It deposed the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz and ended the Guatemalan Revolution of 1944–1954. It installed the mi ...

.

In domestic affairs, Eisenhower supported a policy of "modern Republicanism" that occupied a middle ground between

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Democrats and the

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

wing of the Republican Party. Eisenhower continued

New Deal programs, expanded

Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

, and prioritized a balanced budget over tax cuts. He played a major role in establishing the

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. T ...

, a massive infrastructure project consisting of tens of thousands of miles of

divided highway

A dual carriageway ( BE) or divided highway ( AE) is a class of highway with carriageways for traffic travelling in opposite directions separated by a central reservation (BrE) or median (AmE). Roads with two or more carriageways which are ...

s. After the launch of

Sputnik 1, Eisenhower signed the

National Defense Education Act and presided over the creation of

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

. Though he did not embrace the

Supreme Court's landmark

desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

ruling in the 1954 case of ''

Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'', Eisenhower enforced the Court's holding and signed the first significant civil rights bill since the end of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

.

Eisenhower won the

1956 presidential election in a

landslide and maintained positive approval ratings throughout his tenure, but the launch of Sputnik 1 and a poor economy contributed to Republican losses in the

1958 elections. In the 1960 presidential election, Vice President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

lost by a narrow margin to Kennedy. Eisenhower left office popular with the public but viewed by many commentators as a "do-nothing" president. His reputation improved after the release of his private papers in the 1970s.

Polls of historians and political scientists rank Eisenhower in the top quartile of presidents.

William P. Rogers

William Pierce Rogers (June 23, 1913 – January 2, 2001) was an American diplomat and attorney. He served as United States Attorney General under President Dwight D. Eisenhower and United States Secretary of State under President Richard Nixo ...

was the last surviving member of Eisenhower's cabinet, having died on January 2, 2001.

Election of 1952

Republican nomination

Going into the

1952 Republican presidential primaries, the two major contenders for the

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

presidential nomination were General

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

and Senator

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

of

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. Governor

Earl Warren of

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

and former Governor

Harold Stassen

Harold Edward Stassen (April 13, 1907 – March 4, 2001) was an American politician who was the 25th Governor of Minnesota. He was a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in 1948, considered for a ti ...

of

Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

also sought the nomination. Taft led the

conservative wing of the party, which rejected many of the

New Deal social welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

programs created in the 1930s and supported a

noninterventionist

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

foreign policy. Taft had been a candidate for the Republican nomination twice before but had been defeated both times by

moderate Republicans from New York:

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

in 1940 and

Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

in 1948.

Dewey, the party's presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948, led the moderate wing of the party, centered in the

Eastern states. These moderates supported most of the New Deal and tended to be

interventionists in the

Cold War. Dewey himself declined to run for president a third time, but he and other moderates sought to use his influence to ensure that 1952 Republican ticket hewed closer to their wing of the party.

[ To this end, they assembled a Draft Eisenhower movement in September 1951. Two weeks later, at the National Governors' Conference meeting, seven Republican governors endorsed his candidacy. Eisenhower, then serving as the Supreme Allied Commander of ]NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, had long been mentioned as a possible presidential contender, but he was reluctant to become involved in partisan politics. Nonetheless, he was troubled by Taft's non-interventionist views, especially his opposition to NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, which Eisenhower considered to be an important deterrence

Deterrence may refer to:

* Deterrence theory, a theory of war, especially regarding nuclear weapons

* Deterrence (penology), a theory of justice

* Deterrence (psychology)

Deterrence in relation to criminal offending is the idea or theory that t ...

against Soviet aggression. He was also motivated by the corruption that he believed had crept into the federal government during the later years of the Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran ...

.

Eisenhower suggested in late 1951 that he would not oppose any effort to nominate him for president, although he still refused to seek the nomination actively. In January 1952, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. announced that Eisenhower's name would be entered in the March New Hampshire primary, even though he had not yet officially entered the race. The result in New Hampshire was a solid Eisenhower victory with 46,661 votes to 35,838 for Taft and 6,574 for Stassen. In April, Eisenhower resigned from his NATO command and returned to the United States. The Taft forces put up a strong fight in the remaining primaries, and, by the time of the July 1952 Republican National Convention

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 7 to 11, 1952, and nominated the popular general and war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower of New York, nicknamed "Ike," for president an ...

, it was still unclear whether Taft or Eisenhower would win the presidential nomination.

When the 1952 Republican National Convention opened in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Eisenhower's managers accused Taft of "stealing" delegate votes in Southern states, claiming that Taft's allies had unfairly denied delegate spots to Eisenhower supporters and put Taft delegates in their place. Lodge and Dewey proposed to evict the pro-Taft delegates in these states and replace them with pro-Eisenhower delegates; they called this proposal "Fair Play." Although Taft and his supporters angrily denied this charge, the convention voted to support Fair Play 658 to 548, and Taft lost many Southern delegates. Eisenhower also received two more boosts: first when several uncommitted state delegations, such as Michigan and Pennsylvania, decided to support him; and second, when Stassen released his delegates and asked them to support Eisenhower. The removal of many pro-Taft Southern delegates and the support of the uncommitted states decided the nomination in Eisenhower's favor, which he won on the first ballot. Afterward, Senator Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

of California was nominated by acclamation as his vice-presidential running mate. Nixon, whose name came to the forefront early and often in preconvention conversations among Eisenhower's campaign managers, was selected because of his youth (39 years old) and solid anti-communist record.

General election

Incumbent President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

fared poorly in the polls and decided to not run in 1952. There was no clear frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination. Delegates to the 1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention f ...

in Chicago, nominated Illinois governor Adlai E. Stevenson for president on the third ballot. Senator John Sparkman

John Jackson Sparkman (December 20, 1899 – November 16, 1985) was an American jurist and politician from the state of Alabama. A Southern Democrat, Sparkman served in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1946 and the United St ...

of Alabama was selected as his running mate. The convention ended with widespread confidence that the party had selected a powerful presidential contender who would field a competitive campaign. Stevenson concentrated on giving a series of thoughtful speeches around the nation. Although his style thrilled intellectuals and academics, some political experts wondered if he were speaking "over the heads" of most of his listeners, and they dubbed him an "egghead," based on his baldness and intellectual demeanor. His biggest liability however, was Truman's unpopularity. Even though Stevenson had not been a part of the Truman administration, voters largely ignored his record and burdened him with Truman's. Historian Herbert Parmet says that Stevenson:

Republican strategy during the fall campaign focused on Eisenhower's unrivaled popularity. Ike traveled to 45 of the 48 states; his heroic image and plain talk excited the large crowds who heard him speak from the campaign train's rear platform. In his speeches, Eisenhower never mentioned Stevenson by name, instead relentlessly attacking the alleged failures of the Truman administration: "Korea, Communism, and corruption." In addition to the speeches, he got his message out to voters through 30-second television advertisements; this was the first presidential election in which television played a major role. A potentially devastating allegation hit when Nixon was accused by several newspapers of receiving $18,000 in undeclared "gifts" from wealthy California donors. Eisenhower and his aides considered dropping Nixon from the ticket and picking another running mate. Nixon responded to the allegations in a nationally televised speech, the "

A potentially devastating allegation hit when Nixon was accused by several newspapers of receiving $18,000 in undeclared "gifts" from wealthy California donors. Eisenhower and his aides considered dropping Nixon from the ticket and picking another running mate. Nixon responded to the allegations in a nationally televised speech, the "Checkers speech

The Checkers speech or Fund speech was an address made on September 23, 1952, by Senator Richard Nixon ( R- CA), six weeks before the 1952 United States presidential election, in which he was the Republican nominee for Vice President. Nixon had ...

," on September 23. In this speech, Nixon denied the charges against him, gave a detailed account of his modest financial assets, and offered a glowing assessment of Eisenhower's candidacy. The highlight of the speech came when Nixon stated that a supporter had given his daughters a gift—a dog named "Checkers"—and that he would not return it, because his daughters loved it. The public responded to the speech with an outpouring of support, and Eisenhower retained him on the ticket.

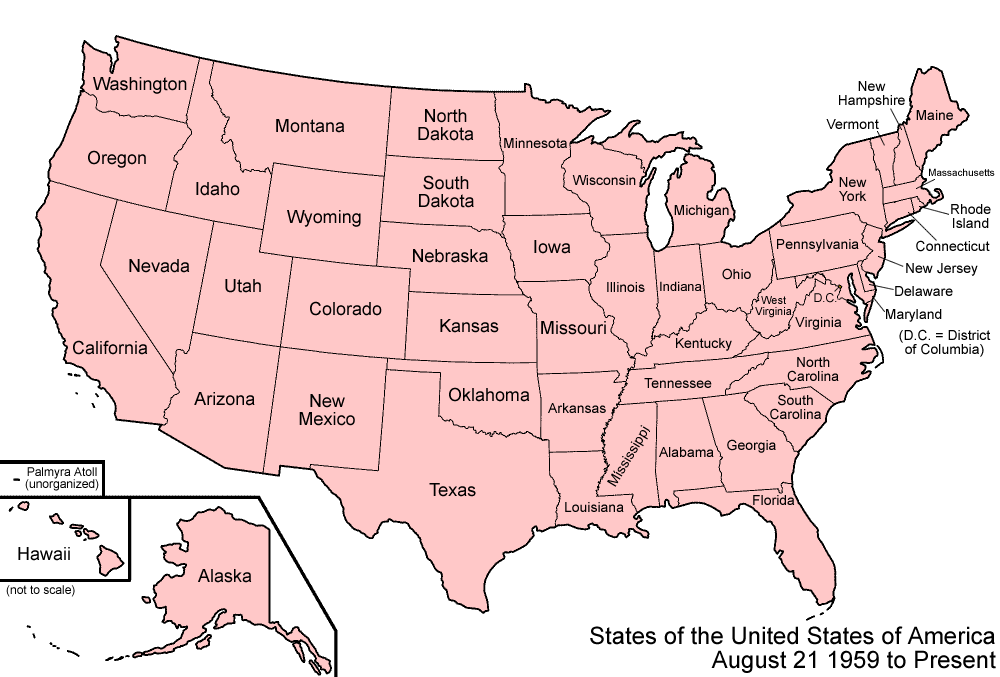

Ultimately, the burden of the ongoing Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, Communist threat, and Truman administration scandals, as well as the popularity of Eisenhower, were too much for Stevenson to overcome. Eisenhower won a landslide victory, taking 55.2 percent of the popular vote and 442 electoral votes. Stevenson received 44.5 percent of the popular vote and 89 electoral votes. Eisenhower won every state outside of the South, as well as Virginia, Florida, and Texas, each of which voted Republican for just the second time since the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. In the concurrent congressional elections,

Republicans won control of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Administration

Eisenhower entered the White House with a strong background in organizing complex operations (such as the invasion of Europe in 1944). More than any previous president he paid attention to improving staff performance and defining duties. He paid special attention to having a powerful Chief of Staff in Sherman Adams

Llewelyn Sherman Adams (January 8, 1899 – October 27, 1986) was an American businessman and politician, best known as White House Chief of Staff for President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the culmination of an 18-year political career that also incl ...

, a former governor.

Cabinet

Eisenhower delegated the selection of his cabinet to two close associates, Lucius D. Clay

General Lucius Dubignon Clay (April 23, 1898 – April 16, 1978) was a senior officer of the United States Army who was known for his administration of occupied Germany after World War II. He served as the deputy to General of the Army Dwight D ...

and Herbert Brownell Jr.

Herbert Brownell Jr. (February 20, 1904 – May 1, 1996) was an American lawyer and Republican politician. From 1953 to 1957, he served as United States Attorney General in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Early life

Brow ...

Brownell, a legal aide to Dewey, became attorney general. The office of Secretary of State went to John Foster Dulles, a long-time Republican spokesman on foreign policy who had helped design the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

and the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

. Dulles would travel nearly during his six years in office. Outside of the cabinet, Eisenhower selected Sherman Adams

Llewelyn Sherman Adams (January 8, 1899 – October 27, 1986) was an American businessman and politician, best known as White House Chief of Staff for President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the culmination of an 18-year political career that also incl ...

as White House Chief of Staff, and Milton S. Eisenhower

Milton Stover Eisenhower (September 15, 1899 – May 2, 1985) was an American academic administrator. He served as president of three major American universities: Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Johns Hopkins Universit ...

, the president's brother and a prominent college administrator, emerged as an important adviser. Eisenhower also elevated the role of the National Security Council, and designated Robert Cutler

Robert Cutler (June 12, 1895 – May 8, 1974) was an American government official who was the first person appointed as the president's National Security Advisor. He served US President Dwight Eisenhower in that role between 1953 and 1955 and fr ...

to serve as the first National Security Advisor.

Eisenhower sought out leaders of big business for many of his other cabinet appointments. Charles Erwin Wilson

Charles Erwin Wilson (July 18, 1890 – September 26, 1961) was an American engineer and businessman who served as United States Secretary of Defense from 1953 to 1957 under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Known as "Engine Charlie", he was pre ...

, the CEO of General Motors, was Eisenhower's first secretary of defense. In 1957, he was replaced by president of Procter & Gamble

The Procter & Gamble Company (P&G) is an American multinational consumer goods corporation headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio, founded in 1837 by William Procter and James Gamble. It specializes in a wide range of personal health/consumer he ...

, Neil H. McElroy

Neil Hosler McElroy (October 30, 1904 – November 30, 1972) was United States Secretary of Defense from 1957 to 1959 under President Eisenhower. He had been president of Procter & Gamble.

Early life and education

Born in Berea, Ohio, to school- ...

. For the position of secretary of the treasury, Ike selected George M. Humphrey, the CEO of several steel and coal companies. His postmaster general, Arthur E. Summerfield, and first secretary of the interior, Douglas McKay

James Douglas McKay (June 24, 1893 – July 22, 1959) was an American businessman and politician from the U.S. state of Oregon. He served in World War I before going into business, where he was most successful as a car dealership owner in Salem ...

, were both automobile distributors. Former senator Sinclair Weeks

Charles Sinclair Weeks (June 15, 1893February 7, 1972), better known as Sinclair Weeks, served as United States Senator from Massachusetts (1944) and as United States Secretary of Commerce from 1953 until 1958, during President Eisenhower's adm ...

became Secretary of Commerce. Eisenhower appointed Joseph Dodge

Joseph Morrell Dodge (November 18, 1890 – December 2, 1964) was a chairman of the Detroit Bank, now Comerica. He later served as an economic adviser for postwar economic stabilization programs in Germany and Japan, headed the American delegation ...

, a longtime bank president who also had extensive government experience, as the director of the Bureau of the Budget. He became the first budget director to be given cabinet-level status.

Other Eisenhower cabinet selections provided patronage to political bases. Ezra Taft Benson

Ezra Taft Benson (August 4, 1899 – May 30, 1994) was an American farmer, government official, and religious leader who served as the 15th United States Secretary of Agriculture during both presidential terms of Dwight D. Eisenhower and ...

, a high-ranking member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

, was chosen as secretary of agriculture; he was the only person appointed from the Taft wing of the party. As the first secretary of the new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Eisenhower named the wartime head of the Army's Women's Army Corps, Oveta Culp Hobby

Oveta Culp Hobby (January 19, 1905 – August 16, 1995) was an American politician and businessperson who served as the first United States secretary of health, education, and welfare from 1953 to 1955. A member of the Republican Party, Hobby wa ...

. She was the second woman to ever be a cabinet member. Martin Patrick Durkin

Martin Patrick Durkin (March 18, 1894 – November 13, 1955) was a U.S. administrator. He served as Secretary of Labor from January 21, 1953, to September 10, 1953, where he was the "plumber" of President Dwight Eisenhower's "Nine Millionair ...

, a Democrat and president of the plumbers and steamfitters union, was selected as secretary of labor. As a result, it became a standing joke that Eisenhower's inaugural Cabinet was composed of "nine millionaires and a plumber." Dissatisfied with Eisenhower's labor policies, Durkin resigned after less than a year in office, and was replaced by James P. Mitchell

James Paul Mitchell (November 12, 1900October 19, 1964) was an American politician and businessman from New Jersey. Nicknamed "the social conscience of the Republican Party," he served as United States Secretary of Labor from 1953 to 1961 during ...

.

Eisenhower suffered a major political defeat when his nomination of Lewis Strauss

Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss ( "straws"; January 31, 1896January 21, 1974) was an American businessman, philanthropist, and naval officer who served two terms on the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the second as its chairman. He was a major ...

as a later Secretary of Commerce was defeated in the U.S. Senate in 1959, in part due to Strauss's role in the Oppenheimer security hearing

The Oppenheimer security hearing was a 1954 proceeding by the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that explored the background, actions, and associations of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American scientist who had headed the Los Alamos Lab ...

.

Vice presidency

Eisenhower, who disliked partisan politics and politicians, left much of the building and sustaining of the Republican Party to Vice President Nixon. Eisenhower knew how ill-prepared Vice President Truman had been on major issues such as the atomic bomb when he suddenly became president in 1945, and therefore made sure to keep Nixon fully involved in the administration. He gave Nixon multiple diplomatic, domestic, and political assignments so that he "evolved into one of Ike's most valuable subordinates." The office of vice president was thereby fundamentally upgraded from a minor ceremonial post to a major role in the presidential team. Nixon went well beyond the assignment, " hrowinghimself into state and local politics, making hundreds of speeches across the land. With Eisenhower uninvolved in party building, Nixon became the ''de facto'' national GOP leader."

Press corps

In his two terms he delivered about 750 speeches and conducted 193 news conferences. On January 19, 1955, Eisenhower became the first president to conduct a televised news conference.

Reporters found performance at press conferences as awkward. Some concluded mistakenly that he was ill-informed or merely a figurehead. At times, he was able to use his reputation to deliberately obfuscate his position on difficult subjects.

His press secretary

A press secretary or press officer is a senior advisor who provides advice on how to deal with the news media and, using news management techniques, helps their employer to maintain a positive public image and avoid negative media coverage.

Dut ...

, James Hagerty, was known for providing much more detail on the lifestyle of the president than previous press secretaries; for example, he covered in great detail Eisenhower's medical condition. Most of the time, he handled routine affairs such as daily reports on presidential activities, defending presidential policies, and assisting diplomatic visitors. He handled embarrassing episodes, such as those related to the Soviet downing of an American spy plane, the U-2 in 1960. He handled press relations on Eisenhower's international trips, sometimes taking the blame from a hostile foreign press. Eisenhower often relied upon him for advice about public opinion, and how to phrase complex issues. Hagerty had a reputation for supporting civil rights initiatives. Historian Robert Hugh Ferrell

Robert Hugh Ferrell (May 8, 1921 – August 8, 2018) was an American historian and a prolific author or editor of more than 60 books on a wide range of topics, including the U.S. presidency, World War I, and U.S. foreign policy and diplom ...

considered him to be the best press secretary in presidential history, because he "organized the presidency for the single innovation in press relations that has itself almost changed the nature of the nation's highest office in recent decades."

Continuity of government

A group of three federal government officials and six private U.S. citizens was secretly tasked by the president in 1958 to serve as federal administrators in the event of a national emergency, such as a nuclear attack. Eisenhower discussed the issues with each appointee and then personally sent letters of confirmation. The selection and appointment of these administrator-designates was classified Top Secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kn ...

. In an emergency, each administrator was to take charge of a specifically activated agency to maintain the continuity of government

Continuity of government (COG) is the principle of establishing defined procedures that allow a government to continue its essential operations in case of a catastrophic event such as nuclear war.

COG was developed by the British government befo ...

. Named to the group were:

* Theodore F. Koop, Vice President of CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

Emergency Censorship Agency

* Frank Stanton, President of CBSEmergency Communications Agency

* John Ed Warren, Senior Vice President of First National City Bank

Citibank, N. A. (N. A. stands for " National Association") is the primary U.S. banking subsidiary of financial services multinational Citigroup. Citibank was founded in 1812 as the City Bank of New York, and later became First National City ...

Emergency Energy and Minerals Agency

* Ezra Taft Benson

Ezra Taft Benson (August 4, 1899 – May 30, 1994) was an American farmer, government official, and religious leader who served as the 15th United States Secretary of Agriculture during both presidential terms of Dwight D. Eisenhower and ...

, Secretary of AgricultureEmergency Food Agency

* Aksel Nielsen, President of Title Guaranty CompanyEmergency Housing Agency

* James P. Mitchell

James Paul Mitchell (November 12, 1900October 19, 1964) was an American politician and businessman from New Jersey. Nicknamed "the social conscience of the Republican Party," he served as United States Secretary of Labor from 1953 to 1961 during ...

, Secretary of LaborEmergency Manpower Agency

* Harold Boeschenstein, President of Owens-Corning

Owens Corning is an American company that develops and produces insulation, roofing, and fiberglass composites and related materials and products. It is the world's largest manufacturer of fiberglass composites. It was formed in 1935 as a partn ...

FiberglassEmergency Production Agency

* William McChesney Martin

William McChesney Martin Jr. (December 17, 1906 – July 27, 1998) was an American business executive who served as the 9th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1951 to 1970, the longest serving in that position. He was nominated to the post ...

, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, commonly known as the Federal Reserve Board, is the main governing body of the Federal Reserve System. It is charged with overseeing the Federal Reserve Banks and with helping implement the m ...

Emergency Stabilization Agency

* Frank Pace, Executive Vice President of General DynamicsEmergency Transport Agency (resigned January 8, 1959)

* George P. Baker, Dean of Harvard Business SchoolEmergency Transport Agency (after January 8, 1959)

Judicial appointments

Eisenhower appointed five justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1953, Eisenhower nominated Governor Earl Warren to succeed Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson. Many conservative Republicans opposed Warren's nomination, but they were unable to block the appointment, and Warren's nomination was approved by the Senate in January 1954. Warren presided over a court that generated numerous liberal rulings on various topics, beginning in 1954 with the desegregation case of ''

Eisenhower appointed five justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1953, Eisenhower nominated Governor Earl Warren to succeed Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson. Many conservative Republicans opposed Warren's nomination, but they were unable to block the appointment, and Warren's nomination was approved by the Senate in January 1954. Warren presided over a court that generated numerous liberal rulings on various topics, beginning in 1954 with the desegregation case of ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

''. Eisenhower approved of the ''Brown'' decision. Robert H. Jackson's death in late 1954 generated another vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

to succeed Jackson. Harlan joined the conservative bloc on the bench, often supporting the position of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

.Sherman Minton

Sherman "Shay" Minton (October 20, 1890 – April 9, 1965) was an American politician and jurist who served as a U.S. senator from Indiana and later became an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; he was a member of the ...

resigned in 1956, Eisenhower nominated state supreme court justice William J. Brennan

William Joseph "Bill" Brennan Jr. (April 25, 1906 – July 24, 1997) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990. He was the seventh-longest serving justice ...

to the Supreme Court. Eisenhower hoped that the appointment of Brennan, a liberal-leaning Catholic, would boost his own re-election campaign. Opposition from Senator Joseph McCarthy and others delayed Brennan's confirmation, so Eisenhower placed Brennan on the court via a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

in 1956; the Senate confirmed Brennan's nomination in early 1957. Brennan joined Warren as a leader of the court's liberal bloc. Stanley Reed's retirement in 1957 created another vacancy, and Eisenhower nominated federal appellate judge Charles Evans Whittaker

Charles Evans Whittaker (February 22, 1901 – November 26, 1973) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1957 to 1962. After working in private practice in Kansas City, Missouri, he was nominated for the United States Di ...

, who would serve on the Supreme Court for just five years before resigning. The fifth and final Supreme Court vacancy of Eisenhower's tenure arose in 1958 due to the retirement of Harold Burton Harold Burton may refer to:

* Harold H. Burton (1888–1964), mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, member of the United States Senate and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

* Harold W. Burton

Harold William Burton (October 23, 188 ...

. Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart (January 23, 1915 – December 7, 1985) was an American lawyer and judge who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. During his tenure, he made major contributions to, among other areas, ...

to succeed Burton, and Stewart became a centrist on the court.United States Courts of Appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals f ...

, and 129 judges to the United States district courts

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district cou ...

. Since nearly all were appointed to serve specific geographical area, their regional origins matched the national population. All were white men. Most judges had an upper-middle-class background. One in five attended an Ivy League undergraduate college; half attended an Ivy League law school. Party affiliation was decisive: 93% of the men were Republicans, 7% Democrats; relatively few had been conspicuous in elective politics. Nearly 80% of the men were Protestants, 15% Catholic, and 6% Jewish.

Foreign affairs

Cold War

The Cold War dominated international politics in the 1950s. As both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, any conflict presented the risk of escalation into nuclear warfare. The isolationist element led by Senator Taft would avoid war by staying out of European affairs. Eisenhower's 1952 candidacy was motivated by his opposition to Taft's isolationist views in opposition to NATO and American reliance on collective security with Western Europe. Eisenhower continued the basic Truman administration policy of

The Cold War dominated international politics in the 1950s. As both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, any conflict presented the risk of escalation into nuclear warfare. The isolationist element led by Senator Taft would avoid war by staying out of European affairs. Eisenhower's 1952 candidacy was motivated by his opposition to Taft's isolationist views in opposition to NATO and American reliance on collective security with Western Europe. Eisenhower continued the basic Truman administration policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

of Soviet expansion but added a concern with propaganda suggesting eventual liberation of Eastern Europe.

Eisenhower's overall Cold War policy was codified in NSC174, which held that the rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, w ...

of Soviet influence was a long-term goal, but that NATO would not provoke war with the Soviet Union. Peace would be maintained by being so much stronger in terms of atomic weapons than the USSR that it would never risk using its much larger land-based army to attack Western Europe. He planned for to mobilize psychological insights, CIA intelligence and American scientific technological superiority counter conventional Soviet forces.

After Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

died in March 1953, Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

took leadership of the Soviet Union. Malenkov proposed a "peaceful coexistence" with the West, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

proposed a summit of the world leaders. Fearing that the summit would delay the rearmament of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, and skeptical of Malenkov's intentions, Eisenhower rejected the summit idea. In April, Eisenhower delivered his "Chance for Peace speech

The Chance for Peace speech, also known as the Cross of Iron speech, was an address given by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower on April 16, 1953, shortly after the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Speaking only three months into his preside ...

," in which he called for an armistice in Korea, free elections to re-unify Germany, the "full independence" of Eastern European nations, and United Nations control of atomic energy. Though well received in the West, the Soviet leadership viewed Eisenhower's speech as little more than propaganda. In 1954, a more confrontational leader, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, took charge in the Soviet Union. Eisenhower became increasingly skeptical of the possibility of cooperation with the Soviet Union after it refused to support his Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

proposal, which called for the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the creation of peaceful nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced ...

plants.

National security policy

Eisenhower unveiled the ''New Look'', his first national security policy, on October 30, 1953. It reflected his concern for balancing the Cold War military commitments of the United States with the risk of overwhelming the nation's financial resources. The new policy emphasized reliance on strategic nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s, rather than conventional military power, to deter both conventional and nuclear military threats. The U.S. military developed a strategy of nuclear deterrence based upon the triad of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), strategic bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).retaliate

Revenge is committing a harmful action against a person or group in response to a grievance, be it real or perceived. Francis Bacon described revenge as a kind of "wild justice" that "does... offend the law ndputteth the law out of office." Pr ...

, fight, and win a nuclear war against the Soviets, although he hoped he would never feel forced to use such weapons.

Ballistic missiles and arms control

Eisenhower held office during a period in which both the United States and the Soviet Union developed nuclear stockpiles theoretically capable of destroying not just each other, but all life on Earth. The United States had tested the first atomic bomb in 1945, and both the superpowers had tested

Eisenhower held office during a period in which both the United States and the Soviet Union developed nuclear stockpiles theoretically capable of destroying not just each other, but all life on Earth. The United States had tested the first atomic bomb in 1945, and both the superpowers had tested thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

s by the end of 1953. Strategic bombers had been the delivery method of previous nuclear weapons, but Eisenhower sought to create a nuclear triad

A nuclear triad is a three-pronged military force structure that consists of land-launched nuclear missiles, nuclear-missile-armed submarines, and strategic aircraft with nuclear bombs and missiles. Specifically, these components are land-based ...

consisting of land-launched nuclear missiles, nuclear-missile-armed submarines, and strategic aircraft. Throughout the 1950s, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBMs) capable of delivering nuclear warheads. Eisenhower also presided over the development of the UGM-27 Polaris

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missi ...

missile, which was capable of being launched from submarines, and continued funding for long-range bombers like the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress.

In January 1956 the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

began developing the Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, an ...

, a Intermediate-range ballistic missile. The program proceeded quickly, and beginning in 1958 the first of 20 Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

Thor squadrons became operational in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. This was the first experiment at sharing strategic nuclear weapons in NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

and led to other placements abroad of American nuclear weapons. Critics at the time, led by Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

levied charges to the effect that there was a "missile gap

In the United States, during the Cold War, the missile gap was the perceived superiority of the number and power of the USSR's missiles in comparison with those of the U.S. (a lack of military parity). The gap in the ballistic missile arsenals did ...

", that is, the U.S. had fallen militarily behind the Soviets because of their lead in space. Historians now discount those allegations, although they agree that Eisenhower did not effectively respond to his critics. In fact, the Soviet Union did not deploy ICBMs until after Eisenhower left office, and the U.S. retained an overall advantage in nuclear weaponry. Eisenhower was aware of the American advantage in ICBM development because of intelligence gathered by U-2 planes, which had begun flying over the Soviet Union in 1956.

The administration decided the best way to minimize the proliferation of nuclear weapons was to tightly control knowledge of gas-centrifuge technology, which was essential to turn ordinary uranium into weapons-grade uranium

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon or has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nucle ...

. American diplomats by 1960 reached agreement with the German, Dutch, and British governments to limit access to the technology. The four-power understanding on gas-centrifuge secrecy would last until 1975, when scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan took the Dutch centrifuge technology to Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

. France sought American help in developing its own nuclear program, but Eisenhower rejected these overtures due to France's instability and his distrust of French leader Charles de Gaulle.

End of the Korean War

During his campaign, Eisenhower said he would go to Korea to end the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, which had begun on 25 June 1950 when North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

invaded South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

. The U.S. had joined the war to prevent the fall of South Korea, later expanding the mission to include victory over the Communist regime in North Korea. The intervention of Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

forces in late 1950 led to a protracted stalemate around the 38th parallel north.

Truman had begun peace talks in mid-1951, but the issue of North Korean and Chinese prisoners remained a sticking point. Over 40,000 prisoners from the two countries refused repatriation, but North Korea and China nonetheless demanded their return. Upon taking office, Eisenhower demanded a solution, warning China that he would use nuclear weapons if the war continued. South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

n leader Syngman Rhee attempted to derail peace negotiations by releasing North Korean prisoners who refused repatriation, but Rhee agreed to accept an armistice after Eisenhower threatened to withdraw all U.S. forces from Korea. On July 27, 1953, the United States, North Korea, and China agreed to the Korean Armistice Agreement

The Korean Armistice Agreement ( ko, 한국정전협정 / 조선정전협정; zh, t=韓國停戰協定 / 朝鮮停戰協定) is an armistice that brought about a complete cessation of hostilities of the Korean War. It was signed by United Sta ...

, ending the Korean War. Historian Edward C. Keefer says that in accepting the American demands that POWs could refuse to return to their home country, "China and North Korea still swallowed the bitter pill, probably forced down in part by the atomic ultimatum." Historian William I. Hitchcock writes that the key factors in reaching the armistice were the exhaustion of North Korean forces and the desire of the Soviet leaders (who exerted pressure on China) to avoid nuclear war.

The armistice led to decades of uneasy peace between North Korea and South Korea. The United States and South Korea signed a defensive treaty in October 1953, and the U.S. would continue to station thousands of soldiers in South Korea long after the end of the Korean War.

Covert actions

Eisenhower, while accepting the doctrine of containment, sought to counter the Soviet Union through more active means as detailed in the State-Defense report NSC 68 United States Objectives and Programs for National Security, better known as NSC68, was a 66-page top secret National Security Council (NSC) policy paper drafted by the Department of State and Department of Defense and presented to President Har ...

. The Eisenhower administration and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

used covert action to interfere with suspected communist governments abroad. An early use of covert action was against the elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mosaddeq, resulting in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup d'état ( fa, کودتای ۲۸ مرداد), was the overthrow of the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in favor of strengthening the monarchical rule of ...

. The CIA also instigated the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état was the result of a CIA covert operation code-named PBSuccess. It deposed the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz and ended the Guatemalan Revolution of 1944–1954. It installed the mi ...

by the local military that overthrew President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán

Jacobo is both a surname and a given name of Spanish origin. Based on the name Jacob. Notable people with the name include:

Surname:

* Alfredo Jacobo (born 1982), Olympic breaststroke swimmer from Mexico

* Cesar Chavez Jacobo, Dominican profession ...

, whom U.S. officials viewed as too friendly toward the Soviet Union. Critics have produced conspiracy theories about the causal factors, but according to historian Stephen M. Streeter, CIA documents show the United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was formed in 1899 fro ...

(UFCO) played no major role in Eisenhower's decision, that the Eisenhower administration did not need to be forced into the action by any lobby groups, and that Soviet influence in Guatemala was minimal.

Defeating the Bricker Amendment

In January 1953, Senator John W. Bricker of Ohio re-introduced the Bricker Amendment

The Bricker Amendment is the collective name of a number of slightly different proposed amendments to the United States Constitution considered by the United States Senate in the 1950s. None of these amendments ever passed Congress. Each of them ...

, which would limit the president's treaty making power and ability to enter into executive agreements with foreign nations. Fears that the steady stream of post-World War II-era international treaties and executive agreements entered into by the U.S. were undermining the nation's sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

united isolationists, conservative Democrats, most Republicans, and numerous professional groups and civic organizations behind the amendment. Believing that the amendment would weaken the president to such a degree that it would be impossible for the U.S. to exercise leadership on the global stage, Eisenhower worked with Senate Minority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

to defeat Bricker's proposal. Although the amendment started out with 56 co-sponsors, it went down to defeat in the U.S. Senate in 1954 on 42–50 vote. Later in 1954, a watered-down version of the amendment missed the required two-thirds majority in the Senate by one vote. This episode proved to be the last hurrah for the isolationist Republicans, as younger conservatives increasingly turned to an internationalism based on aggressive anti-communism, typified by Senator Barry Goldwater.

Europe

Eisenhower sought troop reductions in Europe by sharing of defense responsibilities with NATO allies. Europeans, however, never quite trusted the idea of nuclear deterrence and were reluctant to shift away from NATO into a proposed European Defence Community (EDC). Like Truman, Eisenhower believed that the rearmament of West Germany was vital to NATO's strategic interests. The administration backed an arrangement, devised by Churchill and British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, in which West Germany was rearmed and became a fully sovereign member of NATO in return for promises not establish atomic, biological, or chemical weapons programs. European leaders also created the Western European Union

The Western European Union (WEU; french: Union de l'Europe occidentale, UEO; german: Westeuropäische Union, WEU) was the international organisation and military alliance that succeeded the Western Union (WU) after the 1954 amendment of the 1948 ...

to coordinate European defense. In response to the integration of West Germany into NATO, Eastern bloc leaders established the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

. Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, which had been jointly-occupied by the Soviet Union and the Western powers, regained its sovereignty with the 1955 Austrian State Treaty

The Austrian State Treaty (german: Österreichischer Staatsvertrag ) or Austrian Independence Treaty re-established Austria as a sovereign state. It was signed on 15 May 1955 in Vienna, at the Schloss Belvedere among the Allied occupying p ...

. As part of the arrangement that ended the occupation, Austria declared its neutrality after gaining independence.

The Eisenhower administration placed a high priority on undermining Soviet influence on Eastern Europe, and escalated a propaganda war under the leadership of Charles Douglas Jackson. The United States dropped over 300,000 propaganda leaflets in Eastern Europe between 1951 and 1956, and Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a United States government funded organization that broadcasts and reports news, information, and analysis to countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Caucasus, and the Middle East where it says tha ...

sent broadcasts throughout the region. A 1953 uprising in East Germany briefly stoked the administration's hopes of a decline in Soviet influence, but the USSR quickly crushed the insurrection. In 1956, a major uprising broke out in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

. After Hungarian leader Imre Nagy promised the establishment of a multiparty democracy and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev dispatched 60,000 soldiers into Hungary to crush the rebellion. The United States strongly condemned the military response but did not take direct action, disappointing many Hungarian revolutionaries. After the revolution, the United States shifted from encouraging revolt to seeking cultural and economic ties as a means of undermining Communist regimes. Among the administration's cultural diplomacy initiatives were continuous goodwill tours by the "soldier-musician ambassadors" of the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra

The Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra was the only symphonic orchestral ensemble ever created under the supervision of the United States Army. Founded by the composer Samuel Adler, its members participated in the cultural diplomacy initiatives of ...

.

In 1953, Eisenhower opened relations with Spain under dictator Francisco Franco. Despite its undemocratic nature, Spain's strategic position in light of the Cold War and anti-communist position led Eisenhower to build a trade and military alliance with the Spanish through the Pact of Madrid

The Pact of Madrid, signed on 23 September 1953 by Francoist Spain and the United States, was a significant effort to break the international isolation of Spain after World War II, together with the Concordat of 1953. This development came at a ...

. These relations brought an end to Spain's isolation after World War II, which in turn led to a Spanish economic boom known as the Spanish miracle

The Spanish miracle ( es, el milagro español) refers to a period of exceptionally rapid development and growth across all major areas of economic activity in Spain during the latter part of the Francoist regime, from 1959 to 1974, in which GD ...

.

East Asia and Southeast Asia

After the end of World War II, the Communist Việt Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

launched an insurrection against the French-supported State of Vietnam. Seeking to bolster France and prevent the fall of Vietnam to Communism, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations played a major role in financing French military operations in Vietnam. In 1954, the French requested the United States to intervene in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which would prove to be the climactic battle of the First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

. Seeking to rally public support for the intervention, Eisenhower articulated the domino theory

The domino theory is a geopolitical theory which posits that increases or decreases in democracy in one country tend to spread to neighboring countries in a domino effect. It was prominent in the United States from the 1950s to the 1980s in t ...

, which held that the fall of Vietnam could lead to the fall of other countries. As France refused to commit to granting independence to Vietnam, Congress refused to approve of an intervention in Vietnam, and the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. At the contemporaneous Geneva Conference, Dulles convinced Chinese and Soviet leaders to pressure Viet Minh leaders to accept the temporary partition of Vietnam; the country was divided into a Communist northern half (under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as (' Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as P ...

) and a non-Communist southern half (under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem

Ngô Đình Diệm ( or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician. He was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955), and then served as the first president of South Vietnam (Republic o ...

). Despite some doubts about the strength of Diem's government, the Eisenhower administration directed aid to South Vietnam in hopes of creating a bulwark against further Communist expansion. With Eisenhower's approval, Diem refused to hold elections to re-unify Vietnam; those elections had been scheduled for 1956 as part of the agreement at the Geneva Conference.

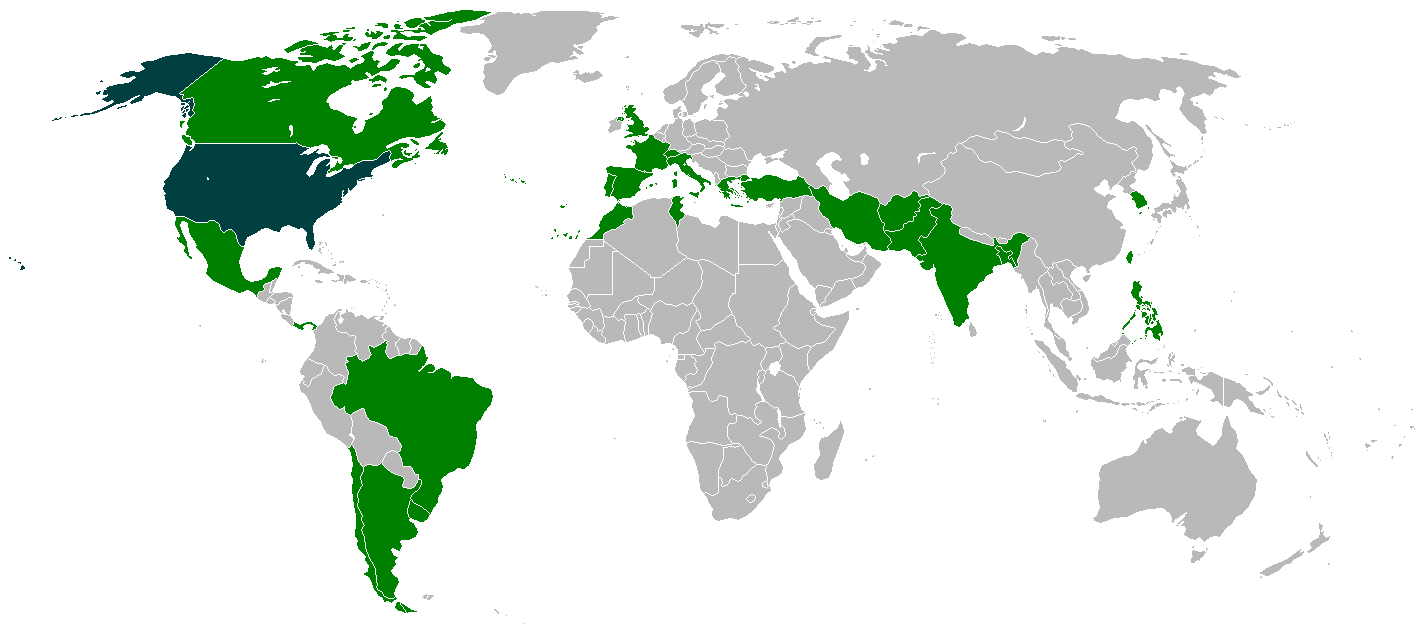

Eisenhower's commitment in South Vietnam was part of a broader program to contain China and the Soviet Union in East Asia. In 1954, the United States and seven other countries created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

(SEATO), a defensive alliance dedicated to preventing the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

. In 1954, China began shelling tiny islands off the coast of Mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

which were controlled by the Republic of China (ROC). The shelling nearly escalated to nuclear war as Eisenhower considered using nuclear weapons to prevent the invasion of Taiwan, the main island controlled by the ROC. The crisis

A crisis ( : crises; : critical) is either any event or period that will (or might) lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society. Crises are negative changes in the human or environmental affair ...

ended when China ended the shelling and both sides agreed to diplomatic talks; a second crisis in 1958 would end in a similar fashion. During the first crisis, the United States and the ROC signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty

The Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty (SAMDT), formally Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of China, was a defense pact signed between the United States and the Republic of China (Taiwan) effective from ...

, which committed the United States to the defense of Taiwan. The CIA also supported dissidents

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

in the 1959 Tibetan uprising

The 1959 Tibetan uprising (also known by other names) began on 10 March 1959, when a revolt erupted in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, which had been under the effective control of the People's Republic of China since the Seventeen Point Agreem ...

, but China crushed the uprising.

In Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

in February 1958 rebels in Sumatra and Sulawesi declared the PRRI-Permesta

Permesta was a rebel movement in Indonesia, its name based on the Universal Struggle Charter (or ''Piagam Perjuangan Semesta'') that was declared on 2 March 1957 by civil and military leaders in East Indonesia. Initially the center of the movem ...

Movement aimed at overthrowing the government of Sukarno. Due to their anti-communist rhetoric, the rebels received money, weapons, and manpower from the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. This support ended when Allen Lawrence Pope

Allen Lawrence Pope (born October 20, 1928) is an American retired military and paramilitary aviator. He rose to international attention as the subject of a diplomatic dispute between the United States and Indonesia after the B-26 Invader aircraf ...

, an American pilot, was shot down after a bombing raid on government-held Ambon

Ambon may refer to:

Places

* Ambon Island, an island in Indonesia

** Ambon, Maluku, a city on Ambon Island, the capital of Maluku province

** Governorate of Ambon, a colony of the Dutch East India Company from 1605 to 1796

* Ambon, Morbihan, a c ...

in April 1958. In April 1958, the central government responded by launching airborne and seaborne military invasions on Padang

Padang () is the capital and largest city of the Indonesian province of West Sumatra. With a Census population of 1,015,000 as of 2022, it is the 16th most populous city in Indonesia and the most populous city on the west coast of Sumatra. Th ...

and Manado

Manado () is the capital city of the Indonesian province of North Sulawesi. It is the second largest city in Sulawesi after Makassar, with the 2020 Census giving a population of 451,916 distributed over a land area of 162.53 km2.Badan Pusa ...