Madison cabinet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The presidency of James Madison began on March 4, 1809, when

With

With

The acquisition of

The acquisition of

General James Wilkinson had been appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory by Jefferson in 1805. In 1809, Madison placed Wilkinson in charge of Terre aux Boeufs on the Louisiana coast to protect the U.S. from invasion. Wilkinson proved to be an incompetent general; many soldiers complained that he was ineffectual: their tents were defective, and they became sick by

General James Wilkinson had been appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory by Jefferson in 1805. In 1809, Madison placed Wilkinson in charge of Terre aux Boeufs on the Louisiana coast to protect the U.S. from invasion. Wilkinson proved to be an incompetent general; many soldiers complained that he was ineffectual: their tents were defective, and they became sick by

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45. In early 1810, Madison began asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the army and navy in preparation for war with Britain.Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47 Congress also passed an act known as

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45. In early 1810, Madison began asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the army and navy in preparation for war with Britain.Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47 Congress also passed an act known as

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

was inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugur ...

as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

, and ended on March 4, 1817. Madison, the fourth United States president, took office after defeating Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney decisively in the 1808 presidential election. He was re-elected four years later, defeating DeWitt Clinton in the 1812 election. His presidency was dominated by the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

with Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. Madison was succeeded by Secretary of State James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, a fellow member of the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

.

Madison's presidency was dominated by the effects of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Initially, American merchants had benefited from the war in Europe since it allowed them to increase their shipping activities, but both the British and French began attacking American ships in an attempt to cut off trade. In response to persistent British attacks on American shipping and the British practice of impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

, the United States declared war on Britain, beginning the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. The war was an administrative morass, as the United States had neither a strong army nor financial system, and the United States failed to conquer Canada. In 1814, the British entered Washington and set fire to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

and the Capitol

A capitol, named after the Capitoline Hill in Rome, is usually a legislative building where a legislature meets and makes laws for its respective political entity.

Specific capitols include:

* United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

* Numerous ...

. However, the United States won several notable naval victories and crushed the resistance of British-allied Native Americans in the West. Shortly after the American triumph at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

, the war ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, in which neither party made major concessions. Despite the lack of gains in the war, the timing of the treaty convinced many Americans that the United States had won a great victory in the war, and Madison's popularity grew. The Federalists collapsed as a national party in the aftermath of the war, which they had strongly opposed.

Madison entered office intending to continue the limited government legacy of his Democratic-Republican predecessor, Thomas Jefferson. However, in the aftermath of the war, Madison favored higher tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

, increased military spending, and the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

. Despite opposition from strict constructionists like John Randolph, much of Madison's post-war agenda was enacted. Madison left office highly popular, and his chosen successor, James Monroe, was elected with little opposition. Though many historians are critical of Madison's presidency, he is generally ranked as an above average president in polls of historians and political scientists.

Election of 1808

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

's second term winding down, and Jefferson's decision to retire widely known, Madison emerged as the leading presidential contender in the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

in 1808. Madison's candidacy faced resistance from Congressman John Randolph, the leader of a Democratic-Republican group known as the Tertium Quids

The tertium quids (sometimes shortened to quids) were various Political faction, factions of the Democratic-Republican Party in the United States from 1804 to 1812.

In Latin, ''tertium quid'' means "a third something". Initially, ''quid'' was a d ...

, which opposed many of Jefferson's policies. A separate group of Democratic-Republicans from New York favored nominating incumbent Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

George Clinton for president. At the congressional nominating caucus The congressional nominating caucus is the name for informal meetings in which American congressmen would agree on whom to nominate for the Presidency and Vice Presidency from their political party.

History

The system was introduced after George W ...

, Madison defeated Clinton and the favored candidate of the Tertium Quid, James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. As the opposition Federalist Party by this time had largely collapsed outside New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, Madison easily defeated its candidate, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, in the general election.Rutland (1999), p. 5 Madison won 122 electoral votes to Pinckney's 47 votes, while Clinton received 6 electoral votes for president from his home state of New York. Clinton was also re-elected as vice president, easily defeating Federalist Rufus King for vice president.

The main issue of the election was the Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

, a general embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

placed on all ships and vessels in U.S. ports and harbors. The banning of exports had hurt merchants and other commercial interests, although it encouraged domestic manufactures. These economic difficulties revived the Federalist opposition, especially in trade-dependent New England. This election was the first of only two instances in American history in which a new president would be elected but the incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

vice president would continue in office.

Administration

Cabinet

Upon his inauguration in 1809, Madison immediately faced opposition to his planned nomination ofSecretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan–American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years o ...

as Secretary of State. Madison chose not to fight Congress for the nomination but kept Gallatin, a carryover from the Jefferson administration, in the Treasury Department. The talented Swiss-born Gallatin was Madison's primary advisor, confidant, and policy planner.Rutland (1990), pp. 32–33. The other members of Madison's initial cabinet, selected more for geographical balance and partisan loyalty than for ability, were less helpful. Secretary of War William Eustis

William Eustis (June 10, 1753 – February 6, 1825) was an early American physician, politician, and statesman from Massachusetts. Trained in medicine, he served as a military surgeon during the American Revolutionary War, notably at the Bat ...

's only military experience had been as a surgeon during the American Revolutionary War, while Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton was an alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomina ...

. Madison appointed Secretary of State Robert Smith only at the behest of Smith's brother, the powerful Senator Samuel Smith; Madison had no affection for either brother. Vice President Clinton also actively worked to undermine Madison's presidency. With a cabinet full of those he distrusted, Madison rarely called cabinet meetings and instead frequently consulted with Gallatin alone.

After feuding with Gallatin, Smith was dismissed in 1811 in favor of James Monroe, and Monroe became a major influence in the Madison administration. Madison appointed several new cabinet members after winning re-election. Hamilton was finally replaced by William Jones, while John Armstrong Jr.

John Armstrong Jr. (November 25, 1758April 1, 1843) was an American soldier, diplomat and statesman who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, U.S. Senator from New York, and United States Secretary of War under President James Madison. A me ...

replaced Eustis, much to the dismay of Monroe, who hated Armstrong. During the War of 1812, Gallatin was sent as a peace envoy to Europe and was successively replaced as Treasury Secretary by Jones (on an interim basis), George W. Campbell

George Washington Campbell (February 9, 1769February 17, 1848) was an American statesman who served as a U.S. Representative, Senator, Tennessee Supreme Court Justice, U.S. Ambassador to Russia and the 5th United States Secretary of the Tre ...

, and finally Alexander Dallas. A frustrated Madison dismissed Armstrong after several failures, replacing him with Monroe. Richard Rush, Benjamin Williams Crowninshield

Benjamin Williams Crowninshield (December 27, 1772 – February 3, 1851) served as the United States Secretary of the Navy between 1815 and 1818, during the administrations of Presidents James Madison and James Monroe.

Early life

Crownins ...

, and Dallas also joined the cabinet in 1814, and for the first time Madison had an effective and harmonious cabinet.

Vice Presidents

Two persons served asvice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

under Madison. George Clinton served from March 4, 1809 until his death on April 20, 1812. Clinton was the first vice president to die in office. As no constitutional provision existed for filling an intra-term vacancy in the vice presidency prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967, the office was left vacant. After the Democratic-Republican ticket's victory in the 1812 presidential election, Elbridge Gerry took office on March 4, 1813. He served until his death on November 23, 1814; the vice presidency remained vacant for the remainder of Madison's second term. Madison is the only president to have had two vice presidents die while in office.

Ambassadorial appointments

Madison appointedWilliam Pinkney

William Pinkney (March 17, 1764February 25, 1822) was an American statesman and diplomat, and was appointed the seventh U.S. Attorney General by President James Madison.

Biography

William Pinkney was born in 1764 in Annapolis in the Province ...

, who had been co-minister with James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

for the preceding two years, ambassador to Great Britain. Pinkney came home in 1811. Madison replaced him with Jonathan Russell

Jonathan Russell (February 27, 1771 – February 17, 1832) was a United States representative from Massachusetts and diplomat. He served the 11th congressional district from 1821 to 1823 and was the first chair of the House Committee on Foreig ...

, who served until the outbreak of war in 1812. Upon resumption of the peace John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

took over this post, having relinquished the office of ambassador to Russia. Madison appointed James A. Bayard to replace Adams in Russia, but he refused the post. It remained vacant until the following administration. For France, Madison left Jefferson's appointee John Armstrong in office until 1810. Madison replaced him with the poet Joel Barlow

Joel Barlow (March 24, 1754 – December 26, 1812) was an American poet, and diplomat, and politician. In politics, he supported the French Revolution and was an ardent Jeffersonian republican.

He worked as an agent for American speculator Wil ...

, who died of pneumonia near the front in Poland. Madison replaced him with William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

until 1814 and then former Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan–American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years o ...

. For Spain Madison kept Chargé d'Affaires George W. Erving, a holdover from the Jefferson administration, raising the post to Minister Plenipotentiary in 1814. For Portugal, Madison appointed Thomas Sumter Jr.

Thomas Sumter (August 14, 1734June 1, 1832) was a soldier in the Colony of Virginia militia; a brigadier general in the South Carolina militia during the American Revolution, a planter, and a politician. After the United States gained independen ...

Judicial appointments

Madison had the opportunity to fill two vacancies on the Supreme Court during his presidency. The first came late in 1810, following the death ofAssociate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

William Cushing

William Cushing (March 1, 1732 – September 13, 1810) was one of the original five associate justices of the United States Supreme Court; confirmed by the United States Senate on September 26, 1789, he served until his death. His Supreme Court ...

. As Supreme Court justices of the time had to ride circuit, Madison had to find a replacement for Cushing who lived in Massachusetts from New England, but there were few qualified potential nominees who were compatible ideologically and politically. At Jefferson's recommendation, Madison first offered the position to former Attorney General Levi Lincoln Sr.

Levi Lincoln Sr. (May 15, 1749 – April 14, 1820) was an American revolutionary, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A Democratic-Republican, he most notably served as Thomas Jefferson's first attorney general, and played a significant ro ...

, but he declined due to ailing health. Madison then nominated Alexander Wolcott, an undisguised partisan of the Democratic-Republicans, but Wolcott was rejected by the Senate. The next nominee was John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, then serving as the ambassador to Russia, but Adams declined as he hoped to one day run for president. Finally, over the objections of Jefferson, Madison offered the position to Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

, a young Democratic-Republican lawyer who had voted against the embargo during his one term in the House. Story was quickly confirmed by the Senate, and would serve until 1845. Another vacancy arose in 1811, following the death of Associate Justice Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

. Madison nominated Gabriel Duvall

Gabriel Duvall (December 6, 1752 – March 6, 1844) was an American politician and jurist. Duvall was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1811 to 1835, during the Marshall Court. Previously, Duvall was the Co ...

to fill the vacancy on November 15, 1811. Duvall was confirmed by the Senate on November 18, 1811, and received commission the same day. Though Jefferson and Madison had hoped to weaken Chief Justice John Marshall's influence on the Marshall Court

The Marshall Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1801 to 1835, when John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Roger Taney t ...

, neither of Madison's appointments altered the Federalist ideological leanings of the court.

Madison appointed eleven other federal judges, two to the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (in case citations, C.C.D.C.) was a United States federal court which existed from 1801 to 1863. The court was created by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.

History

The D.C. ci ...

, and nine to the various United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district co ...

s. One of those judges was appointed twice, to different seats on the same court.

Pre-war economic policies

Madison sought to continue Jefferson's agenda, and in his inaugural address he called for low taxes and a reduction of the national debt. One of the most pressing issues Madison confronted upon taking office was the future of the First Bank of the United States, as the bank's twenty-year charter was scheduled to expire in 1811. A second major issue was the economy, which had entered a slump late in Jefferson's second term. Gallatin favored renewing the bank's charter since it served as an important source of capital and a safe place to deposit government funds, especially in tough economic times. However, most Democratic-Republicans hated the bank, which they saw as a corrupt tool of city-based elites. Madison did not take a strong stand on the issue, and Congress allowed the national bank's charter to lapse. Over the next five years, the number of state-chartered banks more than tripled. Many of these banks issued their ownbanknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

s, and those banknotes became an important part of the U.S. monetary system, as the federal government itself did not issue banknotes at that time.

West Florida

The acquisition of

The acquisition of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

had been one of President Jefferson's major goals. Jefferson and James Monroe, who had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, contended that the purchase had included West Florida, and Madison continued to uphold this claim. Spanish control of its New World colonies had weakened due to the ongoing Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

, and Spain exercised little effective control over West Florida and East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

. Madison was especially concerned about the possibility of the British taking control of the region, which, along with Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, would give the British Empire control of territories on the northern and southern borders of the United States. However, the United States was reluctant to go to war for the territory when France or Great Britain might intervene.

Madison sent William Wykoff into West Florida in the hopes of convincing the settlers of the region to request annexation by the United States. Partly due to Wykoff's prodding, the people of West Florida held the St. Johns Plains Convention in July 1810. Most of those who were elected to the convention had been born in the United States, and they largely favored independence from Spain, but they feared that declaring independence would provoke a Spanish military response. In September 1810, after learning that the Spanish governor of West Florida had requested military assistance from Spain, a militia made up of West Floridians and led by Philemon Thomas

Philemon Thomas (February 9, 1763 – November 18, 1847) was a member of the United States House of Representatives representing the state of Louisiana. He served two terms as a Democrat (1831–1835).

Philemon was born in Orange County, Vi ...

captured the Spanish fort at Baton Rouge. The leaders of the St. Johns Plains Convention declared the establishment of the Republic of West Florida and requested that Madison send troops to prevent a Spanish reprisal. Acting on his own initiative, the governor of Mississippi Territory, David Holmes, ordered U.S. Army soldiers into West Florida. In what became known as the October Proclamation, Madison announced that the United States had taken control of the Republic of West Florida, assigning it to the Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

. Spain retained control of the portion of West Florida east of the Perdido River

Perdido River, historically Rio Perdido (1763), is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 15, 2011 river in the U.S. states of Alabama and Florida; the Perdido, a desig ...

. Madison also employed George Mathews to stir up a rebellion against Spain in East Florida and the remaining Spanish portions of West Florida, but this effort proved unsuccessful. Spain would later recognize U.S. control of West Florida in the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty, in which Spain also ceded control of East Florida.

Wilkinson affair

General James Wilkinson had been appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory by Jefferson in 1805. In 1809, Madison placed Wilkinson in charge of Terre aux Boeufs on the Louisiana coast to protect the U.S. from invasion. Wilkinson proved to be an incompetent general; many soldiers complained that he was ineffectual: their tents were defective, and they became sick by

General James Wilkinson had been appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory by Jefferson in 1805. In 1809, Madison placed Wilkinson in charge of Terre aux Boeufs on the Louisiana coast to protect the U.S. from invasion. Wilkinson proved to be an incompetent general; many soldiers complained that he was ineffectual: their tents were defective, and they became sick by malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, and scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

; dozens died daily. Wilkinson made excuses and a long Congressional investigation was inconclusive. Madison retained Wilkinson because of his political influence in Pennsylvania. After Wilkinson's two battle defeats by the British, Madison finally relieved him from active duty in 1812. Historian Robert Allen Rutland states the Wilkinson affair left "scars on the War Department" and "left Madison surrounded by senior military incompetents ..." at the beginning of the War of 1812.

War of 1812

Prelude to war

TheFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

and the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

had engulfed Europe since the early 1790s. Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

had won a decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz i ...

in 1805, and as a consequence Europe remained mostly at peace for the next few years, but tensions continued on the high seas, where the United States had long traded with both France and Britain. The United States benefited from these wars for much of the period prior to 1807, as American shipping expanded and Napoleon sold Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

to the United States. In 1807, the British announced the Orders in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''King ...

, which called for a blockade on the French Empire. The French announced a policy that allowed for attacks on any American ships that visited British ports, but this policy had relatively little effect as Britain had established naval dominance at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

. In response to subsequent British and French attacks on American shipping, the Jefferson administration had passed the Embargo Act of 1807, which cut off trade with Europe. Congress repealed this act shortly before Madison became president.Rutland (1990), p. 13 In early 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

, which opened trade with foreign powers other than France and Britain. Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between Great Britain and the United States was the impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

of sailors by the British. During the long and expensive war against France, many British citizens were forced by their own government to join the navy, and many of these conscripts defected to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the British seized several U.S. ships and forced captured crewmen, some of whom were not in fact not British subjects, to serve in the British navy. Though Americans were outraged by this impressment, they also refused to take steps to limit it, such as refusing to hire British subjects. For economic reasons, American merchants preferred impressment to giving up their right to hire British sailors.

Although initially promising, President Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the Orders in Council were rejected by British Foreign Secretary George Canning in April 1809. In August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister David Erskine was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" Francis James Jackson.Rutland (1990), pp. 40–44. Madison resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort. British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major British blunder:

The British ambassador in Washington rskinebrought affairs almost to an accommodation, and was ultimately disappointed not by American intransigence but by one of the outstanding diplomatic blunders made by a Foreign Secretary. It was Canning who, in his most irresponsible manner and apparently out of sheer dislike of everything American, recalled the ambassador Erskine and wrecked the negotiations, a piece of most gratuitous folly. As a result, the possibility of a new embarrassment for Napoleon turned into the certainty of a much more serious one for his enemy. Though the British cabinet eventually made the necessary concessions on the score of theOrders-in-Council An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ..., in response to the pressures of industrial lobbying at home, its action came too late…. The loss of the North American markets could have been a decisive blow. As it was by the time the United States declared war, theContinental System The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...f Napoleon F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''. Hist ...was beginning to crack, and the danger correspondingly diminishing. Even so, the war, inconclusive though it proved in a military sense, was an irksome and expensive embarrassment which British statesman could have done much more to avert.

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45. In early 1810, Madison began asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the army and navy in preparation for war with Britain.Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47 Congress also passed an act known as

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45. In early 1810, Madison began asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the army and navy in preparation for war with Britain.Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47 Congress also passed an act known as Macon's Bill Number 2

Macon's Bill Number 2, which became law in the United States on May 14, 1810, was intended to motivate Great Britain and France to stop seizing American ships, cargoes, and crews during the Napoleonic Wars. This was a revision of the original bill ...

, which reopened trade with France and Britain, but promised to reimpose the embargo on one country if the other country agreed to end its attacks on American shipping. Madison, who wished to simply continue the embargo, opposed the law, but he jumped at the chance to use the law's provision enabling a re-imposition of the embargo on one power. Seeking to split the Americans and British, Napoleon offered to end French attacks on American shipping so long as the United States punished any countries that did not similarly end restrictions on trade. Madison accepted Napoleon's proposal in the hope that it would convince the British to revoke the Orders-in-Council, but the British refused to change their policies. Despite assurances to the contrary, the French also continued to attack American shipping.

As the attacks on American shipping continued, both Madison and the broader American public were ready for war with Britain. Some observers believed that the United States might fight a three-way war with both Britain and France, but Democratic-Republicans, including Madison, considered Britain to be far more culpable for the attacks. Many Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to the new nation, and an angry public elected a "war hawk" Congress, led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. With Britain in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans, Madison included, believed that the United States could easily capture Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, at which point the U.S. could use Canada as a bargaining chip for all other disputes or simply retain control of it.. On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war. The declaration was passed along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition from the Federalists and the Northeast, where the economy had suffered during Jefferson's trade embargo.Rutland, ''James Madison: The Founding Father'', pp. 217–24

Madison hurriedly called on Congress to put the country "into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis," specifically recommending enlarging the army, preparing the militia, finishing the military academy, stockpiling munitions, and expanding the navy. Madison faced formidable obstacles—a divided cabinet, a factious party, a recalcitrant Congress, obstructionist governors, and incompetent generals, together with militia who refused to fight outside their states. The most serious problem facing the war effort was lack of unified popular support. There were serious threats of disunion from New England, which engaged in extensive smuggling with Canada and refused to provide financial support or soldiers.Stagg, 1983. Events in Europe also went against the United States. Shortly after the United States declared war, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia, and the failure of that campaign turned the tide against French and towards Britain and her allies. In the years prior to the war, Jefferson and Madison had reduced the size of the military, closed the Bank of the U.S., and lowered taxes. These decisions added to the challenges facing the United States, as by the time the war began, Madison's military force consisted mostly of poorly trained militia members.

Military action

Madison hoped that the war would end in a couple months after the capture of Canada, but his hopes were quickly dashed. Madison had believed the state militias would rally to the flag and invade Canada, but the governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate. Their militias either sat out the war or refused to leave their respective states for action. The senior command at the War Department and in the field proved incompetent or cowardly—the general at Detroit surrendered to a smaller British force without firing a shot. Gallatin discovered the war was almost impossible to fund, since the national bank had been closed, major financiers in the New England refused to help, and government revenue depended largely on tariffs. Though the Democratic-Republican Congress was willing to go against party principle to authorize an expanded military, they refused to levy direct taxes until June 1813. Lacking adequate revenue, and with its request for loans refused by New England bankers, the Madison administration relied heavily on high-interest loans furnished by bankers based in New York City and Philadelphia. The American campaign in Canada, led byHenry Dearborn

Henry Dearborn (February 23, 1751 – June 6, 1829) was an American military officer and politician. In the Revolutionary War, he served under Benedict Arnold in his expedition to Quebec, of which his journal provides an important record ...

, ended with defeat at the Battle of Stoney Creek. Meanwhile, the British armed American Indians, most notably several tribes allied with the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

chief, Tecumseh, in an attempt to threaten American positions in the Northwest.Rutland (1990), pp. 133–134

After the disastrous start to the War of 1812, Madison accepted a Russian invitation to arbitrate the war and sent Gallatin, John Quincy Adams, and James Bayard to Europe in hopes of quickly ending the war. While Madison worked to end the war, the U.S. experienced some military success, particularly at sea. The United States had built up one of the largest merchant fleets in the world, though it had been partially dismantled under Jefferson and Madison. Madison authorized many of these ships to become privateers in the war, and they captured 1,800 British ships. As part of the war effort, an American naval shipyard was built up at Sackets Harbor, New York

Sackets Harbor (earlier spelled Sacketts Harbor) is a village in Jefferson County, New York, United States, on Lake Ontario. The population was 1,450 at the 2010 census. The village was named after land developer and owner Augustus Sackett, who ...

, where thousands of men produced twelve warships and had another nearly ready by the end of the war. The U.S. naval squadron on Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also h ...

successfully defended itself and captured its opponents, crippling the supply and reinforcement of British military forces in the western theater of the war. In the aftermath of the Battle of Lake Erie, General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

defeated the forces of the British and of Tecumseh's Confederacy

Tecumseh's confederacy was a confederation of native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States that began to form in the early 19th century around the teaching of Tenskwatawa (The Prophet).See , pg. 211. The confederation grew ov ...

at the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The Britis ...

. The death of Tecumseh in that battle represented the permanent end of armed Native American resistance in the Old Northwest. In March 1814, General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

broke the resistance of the British-allied Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsBattle of Horseshoe Bend. Despite those successes, the British continued to repel American attempts to invade Canada, and a British force captured  After Napoleon's abdication following the March 1814 Battle of Paris, the British began to shift soldiers to North America. Under General

After Napoleon's abdication following the March 1814 Battle of Paris, the British began to shift soldiers to North America. Under General

Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging the men to give up hunting and become farmers. He stated in 1809 that the federal government's duty was to convert the American Indians by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state". As president, Madison often met with Southeastern and Western Indians, including the Creek and Osage. Rutland (1990), p. 37. After his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson forced the defeated Muscogee to sign the

Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging the men to give up hunting and become farmers. He stated in 1809 that the federal government's duty was to convert the American Indians by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state". As president, Madison often met with Southeastern and Western Indians, including the Creek and Osage. Rutland (1990), p. 37. After his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson forced the defeated Muscogee to sign the

The poorly-attended 1812 Democratic-Republican congressional caucus met in May 1812, and Madison was re-nominated without opposition. A dissident group of New York Democratic-Republicans nominated DeWitt Clinton, the Lieutenant Governor of New York and the nephew of recently deceased Vice President George Clinton, to oppose Madison in the 1812 election. This faction of Democratic-Republicans hoped to unseat the president by forging a coalition among Republicans opposed to the coming war, Democratic-Republicans angry with Madison for not moving more decisively toward war, northerners weary of the Virginia dynasty and southern control of the White House, and disgruntled

The poorly-attended 1812 Democratic-Republican congressional caucus met in May 1812, and Madison was re-nominated without opposition. A dissident group of New York Democratic-Republicans nominated DeWitt Clinton, the Lieutenant Governor of New York and the nephew of recently deceased Vice President George Clinton, to oppose Madison in the 1812 election. This faction of Democratic-Republicans hoped to unseat the president by forging a coalition among Republicans opposed to the coming war, Democratic-Republicans angry with Madison for not moving more decisively toward war, northerners weary of the Virginia dynasty and southern control of the White House, and disgruntled

In the 1816 presidential election, Madison and Jefferson both favored the candidacy of another Virginian, Secretary of State James Monroe. With the support of Madison and Jefferson, Monroe defeated Secretary of War

In the 1816 presidential election, Madison and Jefferson both favored the candidacy of another Virginian, Secretary of State James Monroe. With the support of Madison and Jefferson, Monroe defeated Secretary of War

excerpt

Table of contents

** Wills, Garry. ''Henry Adams and the Making of America.'' (2005); a retelling of Adams' history * Buel Jr, Richard, and Jeffers Lennox. ''Historical dictionary of the early American republic'' (2nd ed. 2016)

excerpt

* Channing, Edward. ''A history of the United States: volume IV: Federalists and Republicans 1789-1815'' (1917) pp. 402–56

online

Old, highly detailed narrative * DeConde, Alexander. ''A History of American Foreign Policy'' (1963

online edition

pp. 97–125 * Ketcham, Ralph. "James Madison" in Henry Graff, ed. ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002

* Rutland, Robert A. ed. ''James Madison and the American Nation, 1751–1836: An Encyclopedia'' (Simon & Schuster, 1994). * Schouler, James. ''History of the United States of America Under the Constitution: vol 2 1801-1817'' (2nd ed. 1894) pp. 310–517; old detailed narrative

complete text online

* Smelser, Marshall. ''The Democratic Republic, 1801 1815'' (1969) in The New American Nation Series.

online

** Brant, James. ''James Madison: Commander in Chief, 1812-1836'' (1961

online

* Single volume condensation of his 6-vol biography * Broadwater, Jeff. ''James Madison: A Son of Virginia and a Founder of a Nation.'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2012). * Chadwick, Bruce. ''James and Dolley Madison: America's First Power Couple'' (Prometheus Books; 2014) 450 pages; detailed popular history * Cost, Jay. ''James Madison: America's First Politician'' (Basic Books, 2021). * Howard, Hugh. ''Mr. and Mrs. Madison's War: America's First Couple and the War of 1812'' (Bloomsbury, 2014). * Ketcham, Ralph. ''James Madison: A Biography'' (1971), 755pp

excerpt

* Rutland, Robert A. ''James Madison: The Founding Father''. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1987. . * Skeen, Carl Edward. "Mr. Madison's Secretary of War." ''Pennsylvania Magazine'' 100 (1976): 336-55. on John Armstrong Jr. * Skeen, C. Edward. ''John Armstrong Jr., 1758-1843: A Biography'' (1981), Scholarly biography of the Secretary of War. * Walters, Raymond. ''Albert Gallatin: Jeffersonian Financier and Diplomat'' (1957).

in JSTOR

* Bickham, Troy. ''The Weight of Vengeance: The United States, the British Empire, and the War of 1812'' (Oxford UP, 2012). * Broadwater, Jeff. "James Madison, the War of 1812 and the Paradox of a Republican Presidency." ''Maryland Historical Magazine,'' 109#4 (2014): 428-51. * Buel, Richard. ''America on the Brink: How the Political Struggle Over the War of 1812 Almost Destroyed the Young Republic'' (2015). * Fitz, Caitlin A. "The Hemispheric Dimensions of Early US Nationalism: The War of 1812, Its Aftermath, and Spanish American Independence." ''Journal of American History'' 102.2 (2015): 356-379. * Gates, Charles M. "The West in American Diplomacy, 1812-1815." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 26.4 (1940): 499-510

in JSTOR

* Hatzenbuehler, Ronald L. "Party Unity and the Decision for War in the House of Representatives, 1812." ''William and Mary Quarterly'' (1972) 29#3: 367-390

in JSTOR

* Hatzenbuehler, Ronald L., and Robert L. Ivie. "Justifying the War of 1812: Toward a Model of Congressional Behavior in Early War Crises." ''Social Science History'' 4.4 (1980): 453-477. * Hill, Peter P. ''Napoleon's Troublesome Americans: Franco-American Relations, 1804-1815'' (Potomac Books, Inc., 2005). * Kaplan, L. S. "France and Madison's decision for war, 1812." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' (1964) 50 : 652–671. * Kleinerman, Benjamin A. "The Constitutional Ambitions of James Madison's Presidency." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 44.1 (2014): 6-26. * Leiner, Frederick C. ''The end of Barbary terror: America's 1815 war against the pirates of North Africa'' (Oxford UP, 2006). * Nester, William R. ''Titan: The Art of British Power in the Age of Revolution and Napoleon'' (U of Oklahoma Press, 2016). * Pancake, John S. "The 'Invisibles': A Chapter in the Opposition to President Madison." ''Journal of Southern History'' 21.1 (1955): 17-37

in JSTOR

* Perkins, Bradford. ''Prologue to War: England and the United States, 1805-1812'' (U of California Press, 1961)

full text online free

* Perkins, Bradford. ''Castlereagh and Adams: England and the United States, 1812-1823'' (U of California Press, 1964). * Risjord, Norman K. "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks and the Nation's Honor." ''William and Mary Quarterly'' (1961) 18#2: 196-210

in JSTOR

* Siemers, David J. "Theories about Theory: Theory‐Based Claims about Presidential Performance from the Case of James Madison." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 38.1 (2008): 78-95. * Siemers, David J. "President James Madison and Foreign Affairs, 1809–1817: Years of Principle and Peril." in Stuart Leibiger ed., ''A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe'' (2012): 207-223. * Snow, Peter. ''When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington'' (2014). * Stagg, John C. A. ''Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American Republic, 1783-1830'' (1983)

online

* Stagg, J.C.A. ''The War of 1812: Conflict for a Continent'' (Cambridge UP, 2012) short survey. * Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the 'Malcontents': The Political Origins of the War of 1812," ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 33#4 (1976), pp. 557–85

in JSTOR

* Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the Coercion of Great Britain: Canada, the West Indies, and the War of 1812," in ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 38#1 (1981), 3–34

in JSTOR

* Stagg, John C. A. ''Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American republic, 1783–1830.'' (Princeton UP, 1983). * Stagg, John C. A. ''Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish-American Frontier, 1776–1821'' (2009) * Stuart, Reginald C. ''Civil-military Relations During the War of 1812'' (ABC-CLIO, 2009). * Sugden, John. "The Southern Indians in the War of 1812: The Closing Phase." ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 60.3 (1982): 273—312. * Trautsch, Jasper M. "' Mr. Madison's War' or the Dynamic of Early American Nationalism?." ''Early American Studies'' 10.3 (2012): 630-670

online

* White, Leonard D. ''The Jeffersonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1801–1829'' (1951), explains the operation and organization of federal administration

online

* Zinman, Donald A. "The Heir Apparent Presidency of James Madison." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 41.4 (2011): 712-726.

excerpt

** Haworth, Peter Daniel. "James Madison and James Monroe Historiography: A Tale of Two Divergent Bodies of Scholarship." in ''A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe'' (2013): 521-539. * Trautsch, Jasper M. "The causes of the War of 1812: 200 years of debate." ''Journal of Military History'' 77.1 (2013): 275-93

online

James Madison: A Resource Guide

at the

The James Madison Papers, 1723–1836

at the Library of Congress *

symposium at the Library of Congress

The Papers of James Madison

subset o

Founders Online

from the National Archives

James Madison

at the

American President: James Madison (1751–1836)

at the

James Madison

at the Online Library of Liberty,

The Papers of James Madison

at the Avalon Project

"Writings of Jefferson and Madison"

from C-SPAN's '' American Writers: A Journey Through History'' * * *

James Madison Personal Manuscripts

{{Authority control 1800s in the United States Madison, James War of 1812 1809 establishments in the United States 1817 disestablishments in the United States 1810s in the United States

Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great Lakes. The fort is on the river's e ...

and burned the American city of Buffalo in late 1813. In early 1814, the British agreed to begin peace negotiations in the town of Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

, and the British pushed for the establishment of an Indian barrier state

The Indian barrier state or buffer state was a British proposal to establish a Native American state in the portion of the Great Lakes region of North America. It was never created. The idea was to create it west of the Appalachian Mountains, bo ...

in the Old Northwest as part of any peace agreement.

After Napoleon's abdication following the March 1814 Battle of Paris, the British began to shift soldiers to North America. Under General

After Napoleon's abdication following the March 1814 Battle of Paris, the British began to shift soldiers to North America. Under General George Izard

George Izard (October 21, 1776 – November 22, 1828) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as the second governor of Arkansas Territory from 1825 to 1828. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 18 ...

and General Jacob Brown

Jacob Jennings Brown (May 9, 1775 – February 24, 1828) was known for his victories as an American army officer in the War of 1812, where he reached the rank of general. His successes on the northern border during that war made him a national ...

, the U.S. launched another invasion of Canada in mid-1814. Despite an American victory at the Battle of Chippawa, the invasion stalled once again. Meanwhile, the British increased the size and intensity of their raids against the Atlantic coast. General William H. Winder

William Henry Winder (February 18, 1775 – May 24, 1824) was an American soldier and a Maryland lawyer. He was a controversial general in the U.S. Army during the War of 1812. On August 24, 1814, as a brigadier general, he led American troops in ...

attempted to bring together a concentrated force to guard against a potential attack on Washington or Baltimore, but his orders were countermanded by Secretary of War Armstrong. The British landed a large force off the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

in August 1814, and the British army approached Washington on August 24. An American force was routed at the Battle of Bladensburg

The Battle of Bladensburg was a battle of the Chesapeake campaign of the War of 1812, fought on 24 August 1814 at Bladensburg, Maryland, northeast of Washington, D.C.

Called "the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms," a British for ...

during which Madison himself took control of some artillery units and directed their attacks, this event being notable as the only time in American history in which a sitting President directed troops in the battlefield; although Madison reportedly performed poorly as a military commander and his efforts were ultimately futile as the battle was eventually lost.

Having won the battle of Blandensburg, British forces set fire to the federal buildings of Washington. Dolley Madison rescued White House valuables and documents shortly before the British burned the White House. The British army next moved on Baltimore, but the British called off the raid after the U.S. repelled a naval attack on Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack ...

. Madison returned to Washington before the end of August, and the main British force departed from the region in September. The British attempted to launch an invasion from Canada, but the U.S. victory at the September 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh ended British hopes of conquering New York.

Anticipating that the British would attack the city of next, newly-installed Secretary of War James Monroe ordered General Jackson to prepare a defense of the city. Meanwhile, the British public began to turn against the war in North America, and British leaders began to look for a quick exit from the conflict. On January 8, 1815, Jackson's force defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

. Just over a month later, Madison learned that his negotiators had reached the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, ending the war without major concessions by either side. Additionally, both sides agreed to establish commissions to settle Anglo-American boundary disputes. Madison quickly sent the Treaty of Ghent to the Senate, and the Senate ratified the treaty on February 16, 1815. To most Americans, the quick succession of events at the end of the war, including the burning of the capital, the Battle of New Orleans, and the Treaty of Ghent, appeared as though American valor at New Orleans had forced the British to surrender. This view, while inaccurate, strongly contributed to the post-war euphoria that persisted for a decade. It also helps explain the significance of the war, even if it was strategically inconclusive. Madison's reputation as president improved and Americans finally believed the United States had established itself as a world power.Rutland (1988), p. 188 Napoleon's defeat at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

brought a permanent end to the Napoleonic Wars, and negotiations between the U.S. and Britain regarding the demilitarization of the Great Lakes led to the signing of the Rush–Bagot Treaty

The Rush–Bagot Treaty or Rush–Bagot Disarmament was a treaty between the United States and Great Britain limiting naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, following the War of 1812. It was ratified by the United States Senate o ...

shortly after Madison left office.

Postwar

Collapse of the Federalists

By 1809, the Federalist Party was no longer competitive outside a few strongholds. Many once-prominent Federalists, including ambassador John Quincy Adams, had joined Madison's Republican Party.Rutland (1990), p. 55. The Federalist Party's standing would continue to decline during Madison's presidency. The War of 1812 was extremely unpopular in New England, and in December 1814 delegates from the six New England states met at theHartford Convention

The Hartford Convention was a series of meetings from December 15, 1814, to January 5, 1815, in Hartford, Connecticut, United States, in which the New England Federalist Party met to discuss their grievances concerning the ongoing War of 1812 and ...

to discuss their grievances. Though some at the convention sought secession, most were not yet willing to call for such a drastic action. The convention sent a delegation, led by Harrison Gray Otis, to Washington, D.C., where the delegates asked for several amendments to the Constitution. The delegates arrived shortly after news of both the Battle of New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent, and the Hartford delegation was largely ignored by Congress. Madison, who had worried that the convention would lead to outright revolt, was relieved that the major outcome of the convention was the request of several impracticable amendments. The Hartford Convention delegates had largely been Federalists, and with Americans celebrating a successful "second war of independence" from Britain, the Hartford Convention became a political millstone around the Federalist Party. After the War of 1812, the Federalist Party slid into national oblivion, although the party would retain pockets of support into the 1820s.

Economic policy

The 14th Congress convened in December 1815, several months after the end of the War of 1812. Recognizing the difficulties of financing the war and the necessity of an institution designed to help regulate currency, Madison proposed the re-establishment of a national bank. He also favored increased spending on the Army and the Navy, as well as atariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

designed to protect American goods from foreign competition. Madison noted that internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

like roads and canals helped promote economic prosperity as well as unity within the United States, and he called for a constitutional amendment to explicitly authorize federal spending on internal improvements. These initiatives represented a major change in course for the Democratic-Republican president, and were opposed by strict constructionists like John Randolph, who stated that Madison's proposals "out-Hamiltons Alexander Hamilton." Madison's tariff proposal did win the support of Jefferson, who stated that "we must now place the manufacturer by the side of the agriculturalist.Howe (2007), pp. 82–84

Responding to Madison's proposals, the 14th Congress compiled one of the most productive legislative records up to that point in history. Madison won the enactment of the Tariff of 1816

The Tariff of 1816, also known as the Dallas Tariff, is notable as the first tariff passed by Congress with an explicit function of protecting U.S. manufactured items from overseas competition. Prior to the War of 1812, tariffs had primarily s ...

relatively easily. The tariff legislation set high import duties for all goods that were produced in the United States at levels that could meet domestic demand; after three years, the rates would decline to approximately 20 percent. Congressman John C. Calhoun argued that the new tariff help create a diversified, self-sufficient economy. The chartering of the new Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

received more opposition, but Congress nonetheless passed a bill granting the bank a twenty-five-year charter.Rutland (1990), pp. 195–198 Under the terms of the bill, the United States supplied one-fifth of the capital for the new bank and would select one quarter of the membership of bank's board of directors. Some Tertium Quids like Nathaniel Macon

Nathaniel Macon (December 17, 1757June 29, 1837) was an American politician who represented North Carolina in both houses of Congress. He was the fifth speaker of the House, serving from 1801 to 1807. He was a member of the United States House of ...

argued that the national bank was unconstitutional, but Madison asserted that the operation of the First Bank of the United States had settled the issue of constitutionality.

Madison also approved federal spending on the Cumberland Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

, which provided a link to the country's western lands. Congress planned for the road to extend from Baltimore to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, which would help provide for the settlement of lands formerly occupied by Tecumseh's Confederacy. In his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed the Bonus Bill of 1817

The Bonus Bill of 1817 was legislation proposed by John C. Calhoun to earmark the revenue "bonus," as well as future dividends, from the recently-established Second Bank of the United States for an internal improvements fund.Stephen MinicucciIn ...

, which would have financed more internal improvements, including roads, bridges, and canals. In making the veto, Madison argued that the General Welfare Clause

A general welfare clause is a section that appears in many constitutions and in some charters and statutes that allows that the governing body empowered by the document to enact laws to promote the general welfare of the people, which is sometimes ...

did not broadly authorize federal spending on internal improvements.

While Madison presided over the implementation of new legislation, Secretary of the Treasury Dallas reorganized the Treasury Department, brought the government budget back into surplus, and put the nation back on the specie system that relied on gold and silver. In 1816, pensions were extended to orphans and widows of the War of 1812 for a period of 5 years at the rate of half pay.

Second Barbary War

During the War of 1812, the Barbary States had stepped up attacks on American shipping. These states, which were nominally vassals of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

but were functionally independent, demanded tribute from countries that traded in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

. With the end of the war, the United States could deploy the now-expanded U.S. Navy against the Barbary States. Congress declared war on Algiers in March 1815, beginning the Second Barbary War

The Second Barbary War (1815) or the U.S.–Algerian War was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen ...

. Seventeen ships, the largest U.S. fleet that had been assembled up to that point in history, were sent to the Mediterranean Sea. After several defeats, Algiers agreed to sign a treaty, and Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

and Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

also subsequently signed treaties. The Barbary States agreed to release all of their prisoners and to stop demanding tributes.Wood, 2009, pp. 696–697.

Indian policy

Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging the men to give up hunting and become farmers. He stated in 1809 that the federal government's duty was to convert the American Indians by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state". As president, Madison often met with Southeastern and Western Indians, including the Creek and Osage. Rutland (1990), p. 37. After his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson forced the defeated Muscogee to sign the

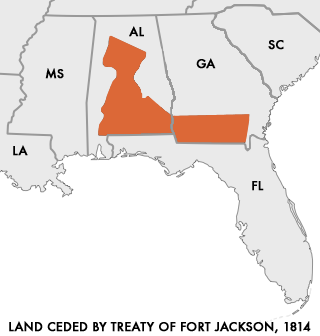

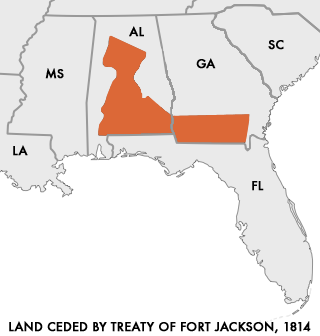

Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging the men to give up hunting and become farmers. He stated in 1809 that the federal government's duty was to convert the American Indians by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state". As president, Madison often met with Southeastern and Western Indians, including the Creek and Osage. Rutland (1990), p. 37. After his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson forced the defeated Muscogee to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

, which forced the Muscogee and the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

(who had been allied with Jackson) to give up control of 22 million acres of land in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Madison initially agreed to restore these lands in the Treaty of Ghent, but Madison backed down in the face of Jackson's resistance. The British abandoned their erstwhile allies, and the U.S. consolidated control of its southwest and northwest frontiers.

Other domestic issues

Constitutional amendments