Quebec was first called ''

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

'' between 1534 and 1763. It was the

most developed colony of

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

as well as New France's centre, responsible for a variety of dependencies (ex.

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

,

Plaisance,

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and the

Pays d'en Haut

The ''Pays d'en Haut'' (; ''Upper Country'') was a territory of New France covering the regions of North America located west of Montreal. The vast territory included most of the Great Lakes region, expanding west and south over time into the ...

). Common themes in Quebec's early history as ''Canada'' include the fur trade -because it was the main industry- as well as the exploration of North America, war against the English, and alliances or war with Native American groups.

Following the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, Quebec became a

British colony in the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. It was first known as the

Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

(1763–1791), then as

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(1791–1841), and then as

Canada East (1841–1867) as a result of the

Lower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion (french: rébellion du Bas-Canada), commonly referred to as the Patriots' War () in French, is the name given to the armed conflict in 1837–38 between rebels and the colonial government of Lower Canada (now south ...

. During this period, the inferior socio-economic status of

francophones

French became an international language in the Middle Ages, when the power of the Kingdom of France made it the second international language, alongside Latin. This status continued to grow into the 18th century, by which time French was the la ...

(because anglophones dominated the natural resources and industries of Quebec), the Catholic church, resistance against cultural assimilation, and isolation from non English-speaking populations were important themes.

Quebec was confederated with

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

,

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, and

New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

in 1867, beginning the

Confederation of Canada

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Dominion of ...

. Important events that mark this period are the World Wars, the

Grande Noirceur

The Grande Noirceur (, English, Great Darkness) refers to the regime of conservative policies undertaken by the governing body of Quebec Premier Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis from 1936 to 1939 and from 1944 to 1959.

Rural areas

Duplessis favour ...

, the

Quiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution (french: Révolution tranquille) was a period of intense socio-political and socio-cultural change in French Canada which started in Quebec after the election of 1960, characterized by the effective secularization of govern ...

(which improved the socio-economic standing of

French Canadians and secularized Quebec), and the emergence of the contemporary

Quebec sovereignty movement

The Quebec sovereignty movement (french: Mouvement souverainiste du Québec) is a political movement whose objective is to achieve the sovereignty of Quebec, a province of Canada since 1867, including in all matters related to any provision o ...

.

These three large periods of Quebec's history are represented on its

coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

with three fleur-de-lis, followed by a lion, and then three maple leaves.

History

Indigenous societies

Aboriginal settlements were located across the area of present-day Quebec before the arrival of Europeans. In the northernmost areas of the province,

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

communities can be found. Other aboriginal communities belong to the following

First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

:

*

Abenakis

*

Algonquins

The Algonquin people are an Indigenous people who now live in Eastern Canada. They speak the Algonquin language, which is part of the Algonquian language family. Culturally and linguistically, they are closely related to the Odawa, Potawatomi ...

*

Atikamekw

*

Crees

*

Innu

*

Malecite

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, or Maliseet (, also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their territory ...

*

Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the nort ...

*

Mohawks

*

Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical country St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our nclusiveland'), which is located in northern Quebec and Labrador, neighb ...

*

Wendats

The aboriginal cultures of present-day Quebec are diverse, with their own languages, way of life, economies, and religious beliefs. Before contact with Europeans, they did not have a written language, and passed their history and other cultural knowledge along to each generation through

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

.

Today around three-quarters of Quebec's aboriginal populations lives in small communities scattered throughout the rural areas of the province, with some living on

reserves.

Jacques Cartier sailed into the St. Lawrence River in 1534 and established an ill-fated colony near present-day Quebec City at the site of

Stadacona

Stadacona was a 16th-century St. Lawrence Iroquoian village not far from where Quebec City was founded in 1608.

History

French explorer and navigator Jacques Cartier, while travelling and charting the Saint Lawrence River, reached the village o ...

, a village of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians.

Linguists and

archaeologists have determined these people were distinct from the Iroquoian nations encountered by later French and Europeans, such as the five nations of the

Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

. Their language was

Laurentian, one of the Iroquoian family. By the late 16th century, they had disappeared from the St. Lawrence Valley.

Paleo-Indian Era (11,000–8000 BC)

Existing archaeological evidence attests to a human presence on the current territory of Quebec sometime around 10,000 BC.

Archaic era (8000–1500 BC)

The Paleoindian period was followed by the

Archaic, a time when major changes occurred in the landscape and the settlement of the territory of Quebec. With the end of glaciation, the inhabitable territory increased in size and the environment (such as climate, vegetation, lakes and rivers) became increasingly stable. Migrations became rarer and moving around became a seasonal activity necessary for hunting, fishing or gathering.

The nomadic populations of the Archaic period were better established and were very familiar with the resources of their territories. They adapted to their surroundings and experienced a degree of population growth. Their diet and tools diversified. Aboriginal peoples used a greater variety of local material, developed new techniques, such as polishing stone, and devised increasingly specialized tools, such as knives, awls, fish hooks, and nets.

Woodland era (3000 BC–1500 AD)

Agriculture appeared experimentally toward the 8th century. It was only in the 14th century that it was fully mastered in the

Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

valley. The Iroquoians cultivated

corn,

marrow,

sunflowers, and

beans.

European explorations

In the 14th century, the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

fell

A fell (from Old Norse ''fell'', ''fjall'', "mountain"Falk and Torp (2006:161).) is a high and barren landscape feature, such as a mountain or moor-covered hill. The term is most often employed in Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Isle of Man, pa ...

. For the

Christian West

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

, this made trade with the

Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

, usually for things like

spices

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

and

gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

, more difficult because

sea routes were now under the control of less cooperative

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

merchants. As such, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

and

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, and then the

English and

French, began to search for a new sea route.

In 1508, only 16 years after the first voyage of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

,

Thomas Auber, who was likely part of a fishing trip near Newfoundland, brought back a few Amerindians to France. This indicates that in the early 16th century, French navigators ventured in the gulf of the St. Lawrence, along with the

Basques and the

Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both in ...

who did the same.

Around 1522–1523, the Italian navigator

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlanti ...

persuaded

King Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

to commission an expedition to find a western route to

Cathay (China). Therefore,

King Francis I launched a maritime expedition in 1524, led by

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlanti ...

, to search for the

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arc ...

. Though this expedition was unsuccessful, it established the name "

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

" for Northeastern North America.

Jacques Cartier's voyages

On June 24, 1534,

French explorer

Jacques Cartier planted a cross on the

Gaspé Peninsula and took possession of the territory in the name of

King François I of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

.

On his second voyage on May 26, 1535, Cartier sailed upriver to the

St. Lawrence Iroquoian villages of

Stadacona

Stadacona was a 16th-century St. Lawrence Iroquoian village not far from where Quebec City was founded in 1608.

History

French explorer and navigator Jacques Cartier, while travelling and charting the Saint Lawrence River, reached the village o ...

, near present-day

Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

, and

Hochelaga, near present-day

Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

. That year, Cartier decided to name the village and its surrounding territories ''

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

'', because he had heard two young natives use the word ''kanata'' ("village" in

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

) to describe the location. 16th-century European cartographers would quickly adopt this name. Cartier also wrote that he thought he had discovered large amounts of diamonds and gold, but this ended up only being

quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

and

pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

. Then, by following what he called the

Great River, he traveled West to the

Lachine Rapids

The Lachine Rapids (french: Rapides de Lachine) are a series of rapids on the Saint Lawrence River, between the Island of Montreal and the south shore. They are located near the former city of Lachine.

The Lachine Rapids contain large standing ...

. There, navigation proved too dangerous for Cartier to continue his journey towards the goal: China. Cartier and his sailors had no choice but to return to Stadaconé and winter there. In the end, Cartier returned to France and took about 10 Native Americans, including the

St. Lawrence Iroquoians chief

Donnacona

Chief Donnacona (died 1539 in France) was the chief of the St. Lawrence Iroquois village of Stadacona, located at the present site of Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

French explorer Jacques Cartier, concluding his second voyage to what is now Can ...

, with him. In 1540, Donnacona told the legend of the

Kingdom of Saguenay to the King of France. This inspired the king to order a third expedition, this time led by

Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval

Jean-François is a French given name. Notable people bearing the given name include:

* Jean-François Carenco (born 1952), French politician

* Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832), French Egyptologist

* Jean-François Clervoy (born 1958), Fr ...

and with the goal of finding the Kingdom of Saguenay. But, it was unsuccessful.

In 1541,

Jean-François Roberval became lieutenant of

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and had the responsibility to build a new

colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

in America. It was Cartier who established the first French settlement on American soil,

Charlesbourg Royal.

France was disappointed after the three voyages of Cartier and did not want to invest further large sums in an adventure with such uncertain outcome. A period of disinterest in the new world on behalf of the French authorities followed. Only at the very end of the 16th century interest in these northern territories was renewed.

Still, even during the time when France did not send official explorers,

Breton and

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

fishermen came to the new territories to stock up on

codfish and

whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' (" tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the head ...

. Since they were forced to stay for a longer period of time, they started to trade their metal objects for fur provided by the indigenous people. This commerce became profitable and thus the interest in the territory was revived.

Fur commerce made a permanent residence in the country worthwhile. Good relations with the aboriginal providers were necessary. For some fishermen however, a seasonal presence was sufficient. Commercial companies were founded that tried to further the interest of the Crown in colonizing the territory. They demanded that France grant a monopoly to one single company. In return, this company would also take over the

colonization of the French American territory. Thus, it would not cost the king much money to build the colony. On the other hand, other merchants wanted commerce to stay unregulated. This controversy was a big issue at the turn of the 17th century.

By the end of the 17th century, a census showed that around 10,000 French settlers were farming along the lower St. Lawrence Valley. By 1700, fewer than 20,000 people of French origin were settled in New France, extending from Newfoundland to the Mississippi, with the pattern of settlement following the networks of the cod fishery and fur trade, although most Quebec settlers were farmers.

New France (1534–1763)

Modern

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

was part of the territory of

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

, the general name for the

North American possessions of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

until 1763. At its largest extent, before the

Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

, this territory included several colonies, each with its own administration:

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

,

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

,

Hudson Bay, and

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

.

The borders of these colonies were not precisely defined, and were open on the western side, as the maps below show:

File:1592 4 Nova Doetecum mr.jpg, 1592–1594: A map of New France made by cartographers Jan Doetecom, Petrus Plancius, and Cornelis Claesz.

Image:Samuel de Champlain Carte geographique de la Nouvelle France.jpg, 1612: A map of New France made by Samuel de Champlain.

File:1730 Canada de l'Isle.jpg, 1730: New France, also referred to as Canada on the map.

Around 1580, France became interested in America again, because the

fur trade had become important in Europe. France returned to America looking for a specific animal: the

beaver. As New France was full of beavers, it became a

colonial-trading post where the main activity was the fur trade in the

Pays-d'en-Haut. In 1600,

Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit

Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit (born c. 1550, died 1603) was a French naval and military captain and a lieutenant of New France who built at Tadoussac, in present-day Quebec, the oldest and strongest surviving French settlement in the Americas.

...

founded the first

permanent trading post in

Tadoussac

Tadoussac () is a village in Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers. The indigenous Innu call the place ''Totouskak'' (plural for ''totouswk'' or ''totochak'') meaning "bosom", probably in reference to the tw ...

for expeditions carried out in the

Domaine du Roy.

In 1603,

Samuel de Champlain travelled to the Saint Lawrence River and, on

Pointe Saint-Mathieu The pointe Saint-Mathieu (Lok Mazé in Breton) is a headland located near Le Conquet in the territory of the commune of Plougonvelin in France, flanked by 20m high cliffs.

Village

At present, there are only a few houses on the point, grouped aroun ...

, established a

defence pact

A defense pact (or defence pact in Commonwealth spelling) is a type of treaty or military alliance in which the signatories promise to support each other militarily and to defend each other.Volker Krause, J. David Singer "Minor Powers, Allianc ...

with the Innu, Wolastoqiyik and Micmacs, that would be "a decisive factor in the maintenance of a French colonial enterprise in America despite an enormous numerical disadvantage vis-à-vis the British colonization in the South".

Thus also began French military support to the

Algonquian and

Huron peoples in defence against

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

attacks and invasions. These Iroquois attacks would become known as the

Beaver Wars and would last from the early 1600s to the early 1700s.

Colony of Canada (1608–1759)

Early years (1608–1663)

Quebec City was founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain. Some other towns were founded before, most famously

Tadoussac

Tadoussac () is a village in Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers. The indigenous Innu call the place ''Totouskak'' (plural for ''totouswk'' or ''totochak'') meaning "bosom", probably in reference to the tw ...

in 1604 which still exists today, but Quebec was the first to be meant as a permanent settlement and not a simple

trading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically the location of the trading post would allow people from one geographic area to tr ...

. Over time, it became a province of Canada and all of New France.

The first version of the town was a single large walled building, called the Habitation. A similar

Habitation was established in Port Royal in 1605, in Acadia. This arrangement was made for protection against perceived threats from the indigenous people. The difficulty of supplying the city of Quebec from France and the lack of knowledge of the area meant that life was hard. A significant fraction of the population died of hunger and diseases during the first winter. However, agriculture soon expanded and a continuous flow of immigrants, mostly men in search of adventure, increased the population.

The settlement was built as a permanent

fur trading

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most ...

outpost. First Nations traded their furs for many French goods such as metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing.

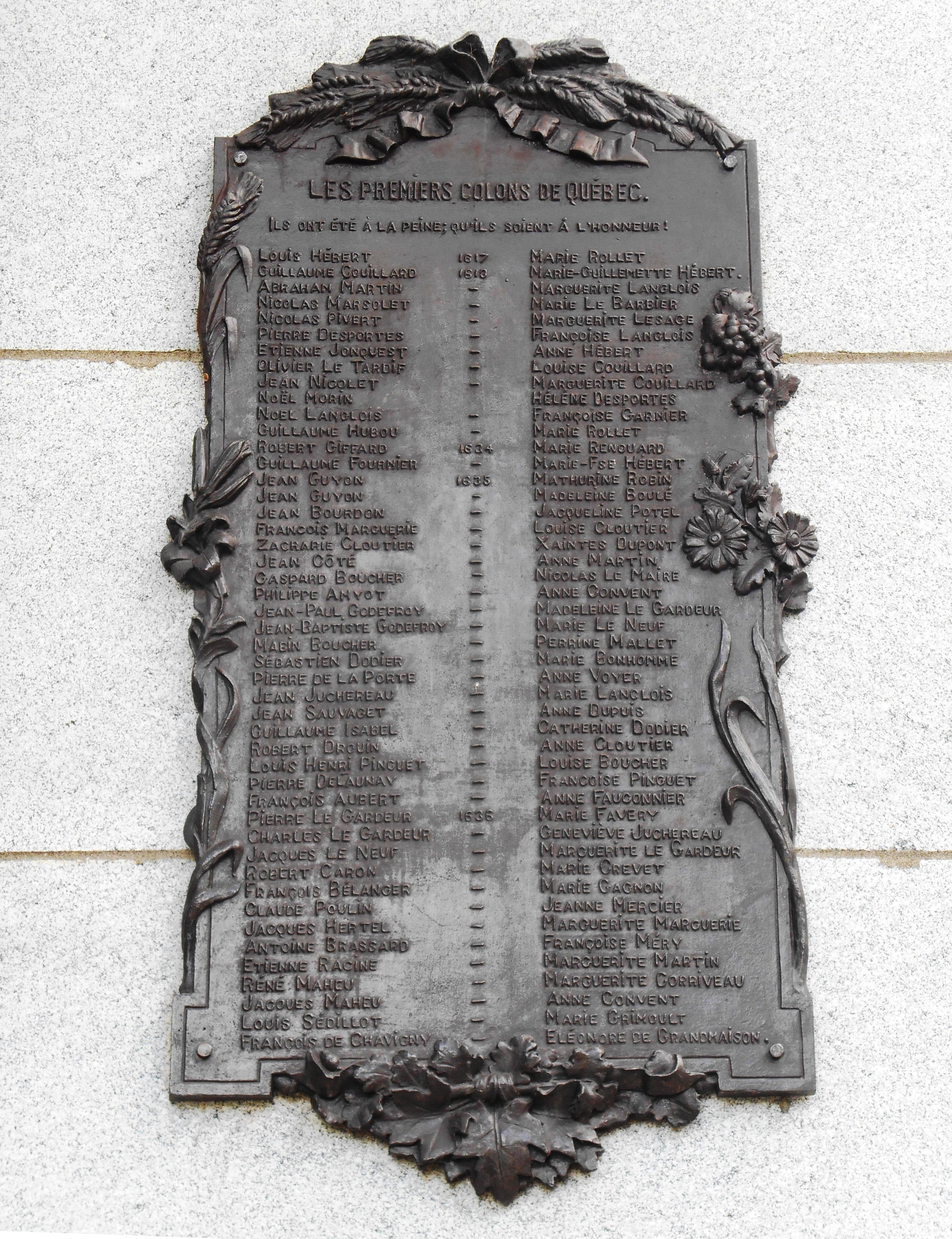

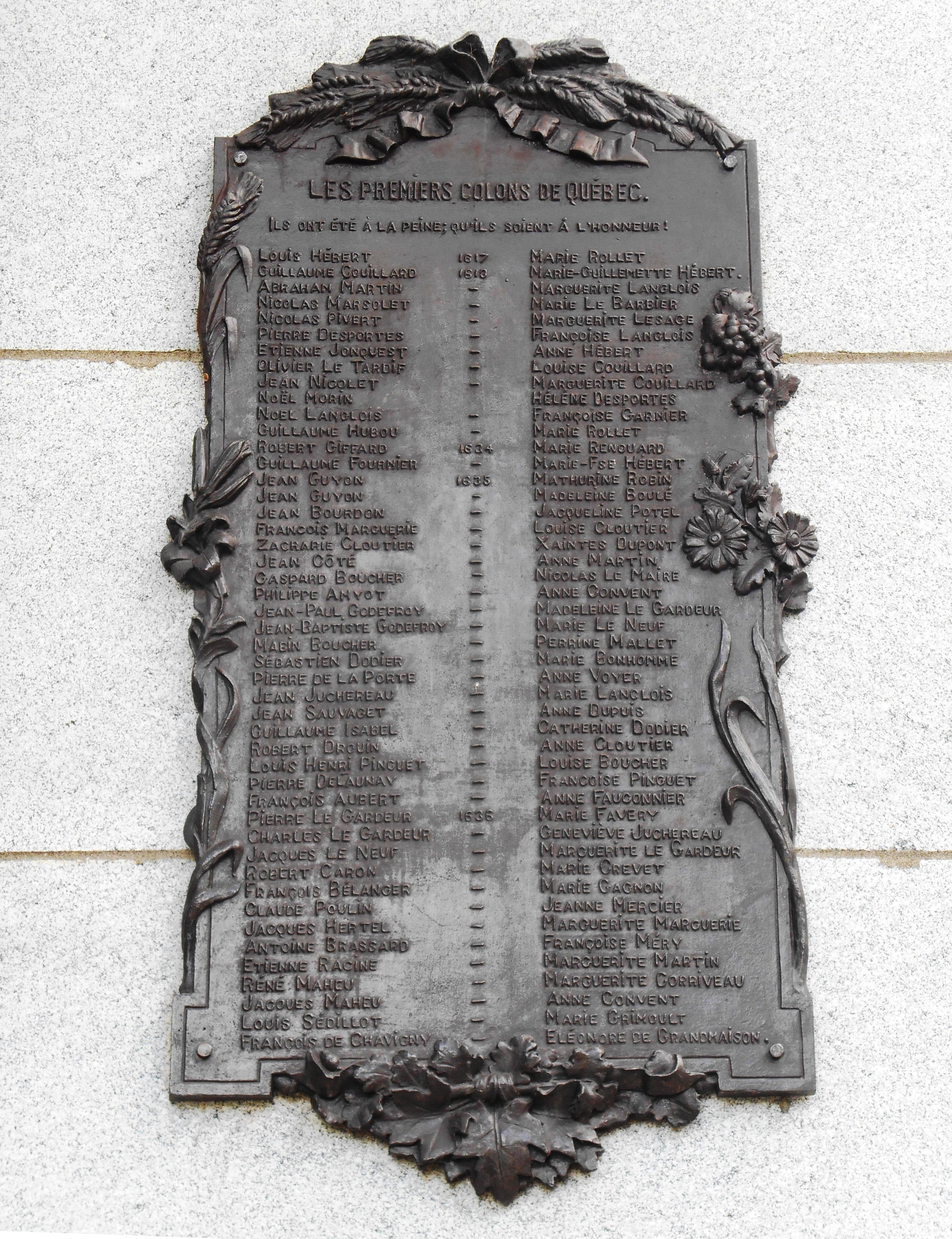

In 1616, the Habitation du Québec became the first permanent establishment of the with the arrival of its two very first settlers:

Louis Hébert and

Marie Rollet

Marie Rollet was a French woman and early settler in Quebec. Her second husband, Louis Hébert, was apothecary to Samuel Champlain's expeditions to Acadia and Quebec on 1606 and 1610–13. When she and her three surviving children traveled with ...

.

The French quickly established trading posts throughout their territory, trading for fur with aboriginal hunters. The ''

coureur des bois'', who were freelance traders, explored much of the area themselves. They kept trade and communications flowing through a vast network along the rivers of the hinterland. They established fur trading forts on the

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

(

Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learne ...

1615),

Hudson Bay (

Radisson and

Groseilliers 1659–60),

Ohio River and

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

(

La Salle 1682), as well as the

Saskatchewan River

The Saskatchewan River (Cree: ''kisiskāciwani-sīpiy'', "swift flowing river") is a major river in Canada. It stretches about from where it is formed by the joining together of the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers to Lake Winn ...

and

Missouri River (

de la Verendrye 1734–1738).

This network was inherited by the English and Scottish traders after the fall of the French Empire in Quebec, and many of the coureur des bois became ''

voyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including th ...

'' for the British.

In 1612, the ''Compagnie de Rouen'' received the royal mandate to manage the operations of

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and the fur trade. In 1621, they were replaced by the ''Compagnie de Montmorency.'' Then, in 1627, they were substituted by the ''

Compagnie des Cent-Associés''. Shortly after being appointed, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés introduced the

Custom of Paris and the

seigneurial system to New France. They also forbade settlement in

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

by anyone other than

Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

s.

The Catholic Church was given ''

en seigneurie'' large and valuable tracts of land estimated at nearly 30% of all the lands granted by the

French Crown

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the firs ...

in

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

.

[Dalton, Roy. ''The Jesuit Estates Question'' 1760–88, p. 60. ]University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university cale ...

, 1968.

Because of

war with England, the first two convoys of ships and settlers bound for the colony were waylaid near

Gaspé by British privateers under the command of three French-Scottish

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

brothers,

David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, Louis and Thomas Kirke. Quebec was effectively cut off. In 1629, there was the

surrender of Quebec

The surrender of Quebec in 1629 was the taking of Quebec City, during the Anglo-French War (1627–1629). It was achieved without battle by English privateers led by David Kirke, who had intercepted the town's supplies.

Background

It began in 1 ...

, without battle, to English

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s led by

David Kirke

Sir David Kirke ( – 1654), also spelt David Ker, was an adventurer, privateer and colonial governor. He is best known for his successful capture of Québec in 1629 during the Thirty Years' War and his subsequent governorship of lands in Ne ...

during the

Anglo-French War

The Anglo-French Wars were a series of conflicts between England (and after 1707, Britain) and France, including:

Middle Ages High Middle Ages

* Anglo-French War (1109–1113) – first conflict between the Capetian Dynasty and the House of Norma ...

. On 19 July 1629, with Quebec completely out of supplies and no hope of relief, Champlain surrendered Quebec to the Kirkes without a fight. Champlain and other colonists were taken to England, where they learned that peace had been agreed (in the 1629

Treaty of Suza) before Quebec's surrender, and the Kirkes were obliged to return their takings. However, they refused, and it was not until the 1632

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye that Quebec and all other captured French possessions in North America were returned to New France. Champlain was restored as de facto governor but died three years later.

In 1633,

Cardinal Richelieu granted a charter to the

Company of One Hundred Associates

The Company of One Hundred Associates (French: formally the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, or colloquially the Compagnie des Cent-Associés or Compagnie du Canada), or Company of New France, was a French trading and colonization company cha ...

, which had been created by the Cardinal himself in 1627. This gave the company control over the booming fur trade and land rights across the territory in exchange for the company supporting and expanding settlement in New France (at the time encompassing Acadia, Quebec, Newfoundland, and Louisiana). Specific clauses in the charter included a requirement to bring 4000 settlers into New France over the next 15 years. The company largely ignored the settlement requirements of their charter and focused on the lucrative fur trade, only 300 settlers arriving before 1640. On the verge of bankruptcy, the company lost its fur trade monopoly in 1641 and was finally dissolved in 1662.

In 1634,

Sieur de Laviolette founded

Trois-Rivières

Trois-Rivières (, – 'Three Rivers') is a city in the Mauricie administrative region of Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saint-Maurice and Saint Lawrence rivers, on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence River across from the city of ...

at the mouth of the

Saint-Maurice River. In 1642,

Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve founded

Ville-Marie (now Montreal) on

Pointe-à-Callière. He chose to found Montreal on an island so that the settlement could be naturally protected against Iroquois invasions. Many heroes of New France come from this period, such as

Dollard des Ormeaux,

Guillaume Couture

Guillaume Couture (January 14, 1618 – April 4, 1701) was a citizen of New France. During his life he was a lay missionary with the Jesuits, a survivor of torture, a member of an Iroquois council, a translator, a diplomat, a militia captain, a ...

,

Madeleine de Verchères and the

Canadian Martyrs.

Royal province (1663–1760)

The establishment of the ''Conseil souverain'', political restructuring which turned New France into a province of France, ended the period of company rule and marked a new beginning in the colonization effort.

In 1663, the

Company of New France ceded Canada to the King,

King Louis XIV, who officially made New France into a royal province of France. New France would now be a

true colony administered by the

Sovereign Council of New France

The Sovereign Council (french: Conseil souverain) was a governing body in New France. It served as both Supreme Court for the colony of New France, as well as a policy-making body, though this latter role diminished over time. The council, though ...

from

Québec, and which functioned off . A

governor-general, assisted by the

intendant of New France and the

bishop of Québec, would go on to govern the colony of Canada (Montreal, Québec, Trois-Rivières and the Pays-d'en-Haut) and its administrative dependencies:

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

,

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and

Plaisance.

The French settlers were mostly farmers and they were known as "

Canadiens

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

" or "

Habitants

Habitants () were French settlers and the inhabitants of French origin who farmed the land along the two shores of the St. Lawrence River and Gulf in what is the present-day Province of Quebec in Canada. The term was used by the inhabitants ...

". Though there was little immigration,

the colony still grew because of the Habitants' high birth rates.

In 1665, the

Carignan-Salières regiment developed the string of fortifications known as the "Valley of Forts" to protect against Iroquois invasions. The Regiment brought along with them 1,200 new men from

Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

,

Liguria

it, Ligure

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

,

Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

and

Savoy. To redress the severe imbalance between single men and women, and boost population growth, King Louis XIV sponsored the passage of approximately 800 young French women (known as ''

les filles du roi'') to the colony. In 1666,

intendant Jean Talon organized the first census of the colony and counted 3,215 Habitants. Talon also enacted policies to diversify agriculture and encourage births, which, in 1672, had increased the population to 6,700 Canadiens.

In 1686, the

Chevalier de Troyes and the

Troupes de la Marine seized three northern forts the English had erected on the lands explored by

Charles Albanel in 1671 near Hudson Bay. Similarly, in the south,

Cavelier de La Salle

A cavalier was a supporter of the Royalist cause during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Cavalier may also refer to:

* Cavalier poets of the English Civil War Poet

* Cavalier Parliament (1661–1679), Restoration Parliament

* Cavalryman

* Palad ...

took for France lands discovered by

Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

and

Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

in 1673 along the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. As a result, the colony of New France's territory grew to extend from Hudson Bay all the way to the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

, and would also encompass the

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

.

In the early 1700s,

Governor Callières concluded the

Great Peace of Montreal

The Great Peace of Montreal (french: La Grande paix de Montréal) was a peace treaty between New France and 39 First Nations of North America that ended the Beaver Wars. It was signed on August 4, 1701, by Louis-Hector de Callière, governor of ...

, which not only confirmed the alliance between the

Algonquian peoples and New France, but also definitively ended the

Beaver Wars. In 1701,

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

founded the district of

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and made its administrative headquarter

Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

. Its headquarter was later moved to

Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

, and then to

. In 1738,

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, extended New France to

Lake Winnipeg

Lake Winnipeg (french: Lac Winnipeg, oj, ᐑᓂᐸᑲᒥᐠᓴᑯ˙ᑯᐣ, italics=no, Weenipagamiksaguygun) is a very large, relatively shallow lake in North America, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. Its southern end is about north of t ...

. In 1742, his

voyageur sons,

François and

Louis-Joseph, crossed the

Great Plains and discovered the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

.

From 1688 onwards, the fierce competition between the

French Empire and

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

to control North America's interior and monopolize the fur trade pitted New France and its

Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

allies against the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and English -primarily in the

Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

- in a series of four successive wars called the

French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

by Americans, and the Intercolonial wars in Quebec. The first three of these wars were

King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand All ...

(1688-1697),

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

(1702-1713), and

King George's War (1744-1748). Many notable battles and exchanges of land took place. In 1690, the

Battle of Quebec became the first time Québec's defences were tested. In 1713, following the

Peace of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

, the

Duke of Orléans ceded Acadia and

Plaisance Bay to the

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

, but retained

Île Saint-Jean, and

Île-Royale (

Cape Breton Island) where the

Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two siege ...

was subsequently erected. These losses were significant since Plaisance Bay was the primary communication route between New France and France, and Acadia contained 5,000

Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

. In the

siege of Louisbourg in 1745, the British were victorious, but returned the city to France after war concessions.

Catholic nuns

Outside the home, Canadian women had few domains which they controlled. An important exception came with Roman Catholic

nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s. Stimulated by the influence in France of the popular religiosity of the

Counter-Reformation, new orders for women began appearing in the seventeenth century and became a permanent feature of Quebec society.

The

Ursuline Sisters arrived in Quebec City in 1639, and in Montreal in 1641. They spread as well to small towns. They had to overcome harsh conditions, uncertain funding, and unsympathetic authorities as they engaged in educational and nursing functions. They attracted endowments and became important landowners in Quebec.

Marie de l'Incarnation

Marie of the Incarnation (28 October 1599 – 30 April 1672) was an Ursuline nun of the French order. As part of a group of nuns sent to New France to establish the Ursuline Order, Marie was crucial in the spread of Catholicism in New France. S ...

(1599–1672) was the mother superior at Quebec, 1639–72.

During the 1759 Quebec Campaign of the Seven Years' War, Augustinian nun Marie-Joseph Legardeur de Repentigny, Sœur de la Visitation, managed the Hôpital Général in Quebec City and oversaw the care of hundreds of wounded soldiers from both the French and British forces. She wrote in after-action report on her work, noting, "The surrender of Quebec only increased our work. The British generals came to our hospital to assure us of their protection and at the same time made us responsible for their sick and wounded." The British officers stationed at the hospital reported on the cleanliness and high quality of the care provided. Most civilians deserted the city, leaving the Hôpital Général as a refugee centre for the poor who had nowhere to go. The nuns set up a mobile aid station that reached out to the cities refugees, distributing food and treating the sick and injured.

British conquest of New France (1754–1763)

In the middle of the 18th century,

British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

had grown to be close to a full-fledged independent country, something they would actually become a few decades later, with more than 1 million inhabitants. Meanwhile,

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

was still seen mostly as a cheap source of natural resources for the metropolis, and had only 60,000 inhabitants. Nevertheless, New France was territorially larger than the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

, but had a population less than 1/10 the size. There was warfare along the borders, with the French supporting Indian raids into the American colonies.

The earliest battles of the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

occurred in 1754 and soon widened into the worldwide

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

. The territory of New France at that time included parts of present-day

Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

, and a series of battles were fought there. The French military enjoyed early successes in these frontier battles, gaining control over several strategic points in 1756 and 1757.

The British sent substantial military forces, while the Royal Navy controlled the Atlantic, preventing France from sending much help. In 1758 the British

captured Louisbourg, gaining control over the mouth of the St. Lawrence, and also took control of key forts on the frontier in battles at

Frontenac and

Duquesne. In spite of the spectacular defeat of the supposed main British thrust in the

Battle of Carillon

The Battle of Carillon, also known as the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga, Chartrand (2000), p. 57 was fought on July 8, 1758, during the French and Indian War (which was part of the global Seven Years' War). It was fought near Fort Carillon (now ...

(in which a banner was supposedly carried that inspired the modern

flag of Quebec

The flag of Quebec, called the (), represents the Canadian province of Quebec. It consists of a white cross on a blue background, with four white fleurs-de-lis.

It was the first provincial flag officially adopted in Canada and was originally sh ...

), the French military position was poor.

In the next phase of the war, begun in 1759, the British aimed directly at the heart of New France.

General James Wolfe led a fleet of 49 ships holding 8,640 British troops to the fortress of Quebec. They disembarked on

Île d'Orléans

Île d'Orléans (; en, Island of Orleans) is an island located in the Saint Lawrence River about east of downtown Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was one of the first parts of the province to be colonized by the French, and a large percentage ...

and on the south shore of the river; the French forces under

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis de Saint-Veran, held the walled city and the north shore. Wolfe laid siege to the city for more than two months, exchanging cannon fire over the river, but neither side could break the siege. As neither side could expect resupply during the winter, Wolfe moved to force a battle. On 5 September 1759, after successfully convincing Montcalm he would attack by the

Bay of Beauport east of the city, the British troops crossed close to Cap-Rouge, west of the city, and successfully climbed the steep Cape Diamond undetected. Montcalm, for disputed reasons, did not use the protection of the city walls and fought on open terrain, in what would be known as the

Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

. The battle was short and bloody; both leaders died in battle, but the British easily won. (''

The Death of General Wolfe'' is a well-known 1770 painting by artist

Benjamin West

Benjamin West, (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as '' The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the '' Treaty of Paris'', and '' Benjamin Franklin Drawin ...

depicting the final moments of Wolfe.)

Now in possession of the main city and capital, and further isolating the inner cities of Trois-Rivières and Montreal from France, the rest of the campaign was only a matter of slowly taking control of the land. While the French had a tactical victory in the

Battle of Sainte-Foy

The Battle of Sainte-Foy (french: Bataille de Sainte-Foy) sometimes called the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille du Quebec), was fought on April 28, 1760 near the British-held town of Quebec in the French province of Canada during the Seven Y ...

outside Quebec in 1760, an attempt to

lay siege to the city ended in defeat the following month when British ships arrived and forced the French besiegers to retreat. An attempt to resupply the French military was further dashed in the naval

Battle of Restigouche, and

Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, New France's last Royal governor,

surrendered Montreal on 8 September 1760. Because the Seven Years' War was still ongoing in Europe, the British put the region under a

British military regime between 1760 and 1763.

Britain's success in the war forced France to cede all of Canada to the British at the

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763 by King

George III of Great Britain

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

set out the terms of government for the newly captured territory, as well as defining the geographic boundaries of the territory.

The rupture from France would provoke a transformation within the

descendants of the Canadiens that would eventually result in the

birth of a new nation whose development and culture would be founded upon, among other things, ancestral foundations anchored in Northeastern America. What British Commissioner

John George Lambton (Lord Durham) would describe in his

1839 report would be the kind of relationship that would reign between the "

Two Solitudes" of Canada for a long time: "I found two nations at war within one state; I found a struggle, not of principles, but of races". Incoming British immigrants would find that Canadiens were as full of national pride as they were, and while these newcomers would see the American territories as a vast ground for colonization and speculation, the Canadiens would regard Quebec as the heritage of their own race - not as a country to colonize, but as a country already colonized.

British North America (1760–1867)

Royal Proclamation (1763–1774)

British rule under Royal Governor

James Murray was benign, with the French Canadians guaranteed their traditional rights and customs. The British

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

united three Quebec districts into the Province of Quebec. It was the British who were the first to use the name "Quebec" to refer to a territory beyond

Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

.

The British tolerated the Catholic Church, and protected the traditional social and economic structure of Quebec. The people responded with one of the highest birth rates ever recorded, 65 births per thousand per year Much French law was retained inside a system of British courts, all under the command of the British governor. The goal was to satisfy the Francophile settlers, albeit to the annoyance of British merchants.

Quebec Act (1774)

With unrest growing in the colonies to the south, which would one day grow into the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, the British were worried that the Canadiens might also support the growing rebellion. At the time, Canadiens formed the vast majority of the population of the Province of Quebec. To secure the allegiance of Canadiens to the British crown, Governor

James Murray and later Governor

Guy Carleton promoted the need for accommodations. This eventually resulted in enactment of the

Quebec Act

The Quebec Act 1774 (french: Acte de Québec), or British North America (Quebec) Act 1774, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which set procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec. One of the principal components of the Act w ...

of 1774. The ''Quebec Act'' was an

Act of the

Parliament of Great Britain setting procedures of governance in the

Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

. Among other components, this act restored the use of the French

civil law for private matters while maintaining the use of the English

common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

for public administration (including criminal prosecution), replaced the oath of allegiance so that it no longer made reference to the

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

faith, and guaranteed free practice of the

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

faith. The purpose of this Act was to secure the allegiance of the French Canadians with unrest growing in the American colonies to the south.

[ See drop-down essay on "Early European Settlement and the Formation of the Modern State"]

American Revolutionary War

When the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

broke out in early 1775, Quebec became a target for American forces, that sought to liberate the French population there from British rule. In September 1775 the

Continental Army began a two-pronged

invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity aggressively enter territory (country subdivision), territory owned by another such entity, gen ...

, with one army capturing Montreal while another traveled through the wilderness of what is now Maine toward Quebec City. The two armies joined forces, but were defeated in the

Battle of Quebec, in which the American General

Richard Montgomery was slain. The Americans were driven back into New York by the arrival of a large army of British troops and German auxiliaries ("

Hessians") in June 1776.

Before and during the American occupation of the province, there was a significant

propaganda war in which both the Americans and the British sought to gain the population's support. The Americans succeeded in raising two regiments in Quebec, led by

James Livingston and

Moses Hazen

Moses Hazen (June 1, 1733 – February 5, 1803) was a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Born in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, he saw action in the French and Indian War with Rogers' Rang ...

, one of which served throughout the war. Hazen's

2nd Canadian Regiment

The 2nd Canadian Regiment (1776–1783), also known as Congress' Own or Hazen's Regiment, was authorized on January 20, 1776, as an Extra Continental regiment and raised in the province of Quebec for service with the American Continental Army ...

served in the

Philadelphia campaign

The Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) was a British effort in the American Revolutionary War to gain control of Philadelphia, which was then the seat of the Second Continental Congress. British General William Howe, after failing to dra ...

and also at the

Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

, and included

Edward Antill, a New Yorker living in Quebec City (who actually led the regiment at Yorktown as Hazen had been promoted to brigadier general),

Clément Gosselin, Germain Dionne, and many others.

Louis-Philippe de Vaudreuil

Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil (18 April 1724 – 14 December 1802) was second in command of the French squadron off America during the American Revolutionary War.

Biography Early life

Louis-Philippe Rigaud de Vaudreuil was ...

, a Quebecker, was with the French Navy in the

Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 17 ...

that prevented the British Navy from reaching

Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Co ...

.

After General

John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several bat ...

's failed 1777

campaign for control of the Hudson River, Quebec was used as a base for raiding operations into the northern parts of the United States until the end of the war. When the war ended, large numbers of

Loyalists fled the United States. Many were resettled into parts of the province that bordered on

Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border ...

. These settlers eventually sought to separate themselves administratively from the French-speaking Quebec population, which occurred in 1791.

Constitutional Act (1791–1840)

The

Constitutional Act of 1791

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791, commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791 (), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed under George III. The current short title has been in use since 1896.

History

The act refor ...

divided Quebec into

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

(the part of present-day Ontario south of

Lake Nipissing plus the current Ontario shoreline of

Georgian Bay

Georgian Bay (french: Baie Georgienne) is a large bay of Lake Huron, in the Laurentia bioregion. It is located entirely within the borders of Ontario, Canada. The main body of the bay lies east of the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. To ...

and

Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

) and

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(the southern part of present-day Quebec).

Newly arrived English-speaking Loyalist refugees had refused to adopt the Quebec seigneurial system of land tenure, or the French civil law system, giving the British reason to separate the English-speaking settlements from the French-speaking territory as administrative jurisdictions. Upper Canada's first capital was Newark (present-day

Niagara-on-the-Lake); in 1796, it was moved to

York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

(now

Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

).

The new constitution, primarily passed to answer the demands of the Loyalists, created a unique situation in Lower Canada. The Legislative Assembly, the only elected body in the colonial government, was continually at odds with the Legislative and Executive branches appointed by the governor. When, in the early 19th century, the

Parti canadien

The Parti canadien () or Parti patriote () was a primarily francophone political party in what is now Quebec founded by members of the liberal elite of Lower Canada at the beginning of the 19th century. Its members were made up of liberal pro ...

rose as a nationalist, liberal and reformist party, a long political struggle started between the majority of the elected representatives of Lower Canada and the colonial government. The majority of the elected representatives in the assembly were members of the francophone professional class: "lawyers, notaries, doctors, innkeepers or small merchants", who comprised 77.4% of the assembly from 1792 to 1836.

By 1809, the government of Newfoundland was no longer willing to supervise the coasts of Labrador. To solve this issue, and as a result of lobbying in

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the British government assigned the coasts of Labrador to the colony of Newfoundland. The inland border between the jurisdiction of Lower Canada and Newfoundland was not well-defined.

In 1813,

Beauport-native

Charles-Michel de Salaberry

Lieutenant Colonel Charles-Michel d'Irumberry de Salaberry, CB (November 19, 1778 – February 27, 1829) was a Canadian military officer and statesman of the seigneurial class who served in various campaigns for the British Army. He won distin ...

became a hero by leading the Canadian troops to victory at the

Battle of Chateauguay, during the

War of 1812