Etymology

The first known mention of the term ''Turk'' (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 ''Türük'' or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 ''Kök Türük'', , Pinyin: Tūjué < Middle Chinese *''tɦut-kyat'' < *''dwət-kuɑt'', Old Tibetan: ''drugu'') Orkhon inscriptions Bain Tsokto inscriptions applied to only one Turkic group, namely, the Göktürks, who were also mentioned, as ''türüg'' ~ ''török'', in the 6th-century Inscription of Hüis Tolgoi, Khüis Tolgoi inscription, most likely not later than 587 AD. A letter by Ishbara Qaghan to Emperor Wen of Sui in 585 described him as "the Great Turk Khan". The Bugut inscription, Bugut (584 CE) and Orkhon inscriptions (735 CE) use the terms ''Türküt'', ''Türk'' and ''Türük''.

During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the ''Turcae'' in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the ''Tyrcae'' among the people of the same area. However, English archaeologist Ellis Minns contended that ''Tyrcae'' Τῦρκαι is "a false correction" for ''Iyrcae'' Ἱύρκαι, a people who dwelt beyond the Thyssagetae, according to Herodotus (Histories (Herodotus), Histories, iv. 22), and were likely Ugric peoples, Ugric ancestors of Magyars. There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names might have been foreign transcriptions of ''Tür(ü)k'', such as Togarmah#Turkic history, ''Togarma'', ''Turukha''/''Turuška'', Turukkaeans, ''Turukku'' and so on; but the information gap is so substantial that any connection of these ancient people to the modern Turks is not possible.

It is generally accepted that the name ''Türk'' is ultimately derived from the Old Turkic language, Old-Turkic migration-term 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 ''Türük''/''Törük'',<"Türk"

The first known mention of the term ''Turk'' (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 ''Türük'' or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 ''Kök Türük'', , Pinyin: Tūjué < Middle Chinese *''tɦut-kyat'' < *''dwət-kuɑt'', Old Tibetan: ''drugu'') Orkhon inscriptions Bain Tsokto inscriptions applied to only one Turkic group, namely, the Göktürks, who were also mentioned, as ''türüg'' ~ ''török'', in the 6th-century Inscription of Hüis Tolgoi, Khüis Tolgoi inscription, most likely not later than 587 AD. A letter by Ishbara Qaghan to Emperor Wen of Sui in 585 described him as "the Great Turk Khan". The Bugut inscription, Bugut (584 CE) and Orkhon inscriptions (735 CE) use the terms ''Türküt'', ''Türk'' and ''Türük''.

During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the ''Turcae'' in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the ''Tyrcae'' among the people of the same area. However, English archaeologist Ellis Minns contended that ''Tyrcae'' Τῦρκαι is "a false correction" for ''Iyrcae'' Ἱύρκαι, a people who dwelt beyond the Thyssagetae, according to Herodotus (Histories (Herodotus), Histories, iv. 22), and were likely Ugric peoples, Ugric ancestors of Magyars. There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names might have been foreign transcriptions of ''Tür(ü)k'', such as Togarmah#Turkic history, ''Togarma'', ''Turukha''/''Turuška'', Turukkaeans, ''Turukku'' and so on; but the information gap is so substantial that any connection of these ancient people to the modern Turks is not possible.

It is generally accepted that the name ''Türk'' is ultimately derived from the Old Turkic language, Old-Turkic migration-term 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 ''Türük''/''Törük'',<"Türk"in ''Turkish Etymological Dictionary'', Sevan Nişanyan. which means 'created, born' or 'strong'. Scholars, including Toru Haneda, Onogawa Hidemi, and Geng Shimin believed that ''Di'', ''Dili'', ''Dingling'', ''Chile'' and ''Tujue'' all came from the Turkic word ''Türk'', which means 'powerful' and 'strength', and its plural form is ''Türküt''. Even though Gerhard Doerfer supports the proposal that ''türk'' means 'strong' in general, Gerard Clauson points out that "the word ''türk'' is never used in the generalized sense of 'strong'" and that ''türk'' was originally a noun and meant "'the culminating point of maturity' (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an [adjective] meaning (of a fruit) 'just fully ripe'; (of a human being) 'in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'". Turkologist Peter B. Golden agrees that the term ''Turk'' has roots in Old Turkic. yet is not convinced by attempts to link ''Dili'', ''Dingling'', ''Chile'', ''Tele'', & ''Tiele'', which possibly transcribed *''tegrek'' (probably meaning 'cart'), to ''Tujue'', which transliterated ''Türküt''. The Chinese Book of Zhou (7th century) presents an etymology of the name ''Turk'' as derived from 'helmet', explaining that this name comes from the shape of a mountain where they worked in the Altai Mountains. Hungarian scholar András Róna-Tas (1991) pointed to a Khotanese-Saka word, ''tturakä'' 'lid', semantically stretchable to 'helmet', as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data. The earliest Turkic-speaking peoples identifiable in Chinese sources are the Yenisei Kyrgyz and Xueyantuo, Xinli, located in South Siberia. Another example of an early Turkic population would be the Dingling. Medieval European chroniclers subsumed various Turkic peoples of the Eurasian steppe under the "umbrella-identity" of the "Scythians". Between 400 CE and the 16th century, Byzantine sources use the name Σκύθαι (''Skuthai'') in reference to twelve different Turkic peoples.G. Moravcsik, ''Byzantinoturcica'' II, p. 236–39 In the modern Turkish language as used in the Republic of Turkey, a distinction is made between "Turks" and the "Turkic peoples" in loosely speaking: the term ''Türk'' corresponds specifically to the "Turkish-speaking" people (in this context, "Turkish-speaking" is considered the same as "Turkic-speaking"), while the term ''Turki, Türki'' refers generally to the people of modern "Turkic Republics" (''Türki Cumhuriyetler'' or ''Türk Cumhuriyetleri''). However, the proper usage of the term is based on Turkic languages, the linguistic classification in order to avoid any political sense. In short, the term ''Türki'' can be used for ''Türk'' or vice versa.

List of ethnic groups

; Historical Turkic groups * Az (people), Az * Dingling * Bulgars * Esegel * Barsils * Alat tribe, Alat * Basmyl * Onogurs * Saragurs * Sabirs * Shatuo * Ongud (from Shatuo) * Göktürks * Oghuz Turks * Kanglys * Khazars * Kipchaks * Kurykans * Cumans, Kumans * Pechenegs * Karluks * Tiele people, Tiele * Tuoba, Tabgach * Turgesh * Tukhsi * Yenisei Kirghiz * Chigils * Toquz Oghuz * Uyghur Khaganate, Orkhon Uyghurs * Yagma * Nushibi * Duolu * Kutrigurs * Utigurs * Yabaku * Yueban * Bulaqs * Xueyantuo * Torks * Chorni Klobuky * Berendei * Yemeks * Naimans (partly) * Keraites (partly) * Merkits (partly) * Uriankhai (partly) Possible Proto-Turkic ancestry, at least partial,Omeljan Pritsak, Pritsak O. & Norman Golb, Golb. N: ''Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century'', Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982. has been posited for Xiongnu, Huns and Pannonian Avars, as well as Tuoba and Rouran Khaganate, Rouran, who were of Proto-Mongols, Proto-Mongolic Donghu people, Donghu ancestry., as well as Tatar confederation, Tatars, Rourans' supposed descendants.Remarks

Language

Distribution

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of some 30 languages, spoken across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, to Siberia and Manchuria and through to the Middle East. Some 170 million people have a Turkic language as their native language;Turkic Language family treeentries provide the information on the Turkic-speaking populations and regions. an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish language, Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers. More than one third of these are ethnic Turkish people, Turks of Turkey, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman Empire, Ottoman-dominated areas of Southern and Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic people are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, and northern Iraq. The Turkic language family is traditionally considered to be part of the proposed Altaic languages, Altaic language family. Howeover since the 1950s, many comparative linguists have rejected the proposal, after supposed cognates were found not to be valid, hypothesized sound shifts were not found, and Turkic and Mongolic languages were found to be converging rather than diverging over the centuries. Opponents of the theory proposed that the similarities are due to language contact, mutual linguistic influences between the groups concerned.Asya Pereltsvaig (2012) ''Languages of the World, An Introduction''. Cambridge University Press. Pages 211–216.

Alphabet

The Turkic alphabets are sets of related alphabets with letters (formerly known as runes), used for writing mostly Turkic languages. Inscriptions in Turkic alphabets were found in Mongolia. Most of the preserved inscriptions were dated to between 8th and 10th centuries CE. The earliest positively dated and read Turkic inscriptions date from the 8th century, and the alphabets were generally replaced by the Old Uyghur alphabet in the East Asia, East and Central Asia, Arabic script in the Middle and Western Asia, Cyrillic in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, and Latin alphabet in Central Europe. The latest recorded use of Turkic alphabets (disambiguation), Turkic alphabet was recorded in Central Europe's Hungary in 1699 CE. The Turkic Old Turkic alphabet, runiform scripts, unlike other typologically close scripts of the world, do not have a uniform palaeography as, for example, have the Gothic language, Gothic runes, noted for the exceptional uniformity of its language and paleography. The Turkic alphabets are divided into four groups, the best known of them is the Orkhon script, Orkhon version of the Enisei group. The Orkhon script is the alphabet used by the Göktürks from the 8th century to record the Old Turkic language. It was later used by the Uyghur Empire; a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian script of the 10th century. Irk Bitig is the only known complete manuscript text written in the Old Turkic script.

History

Origins

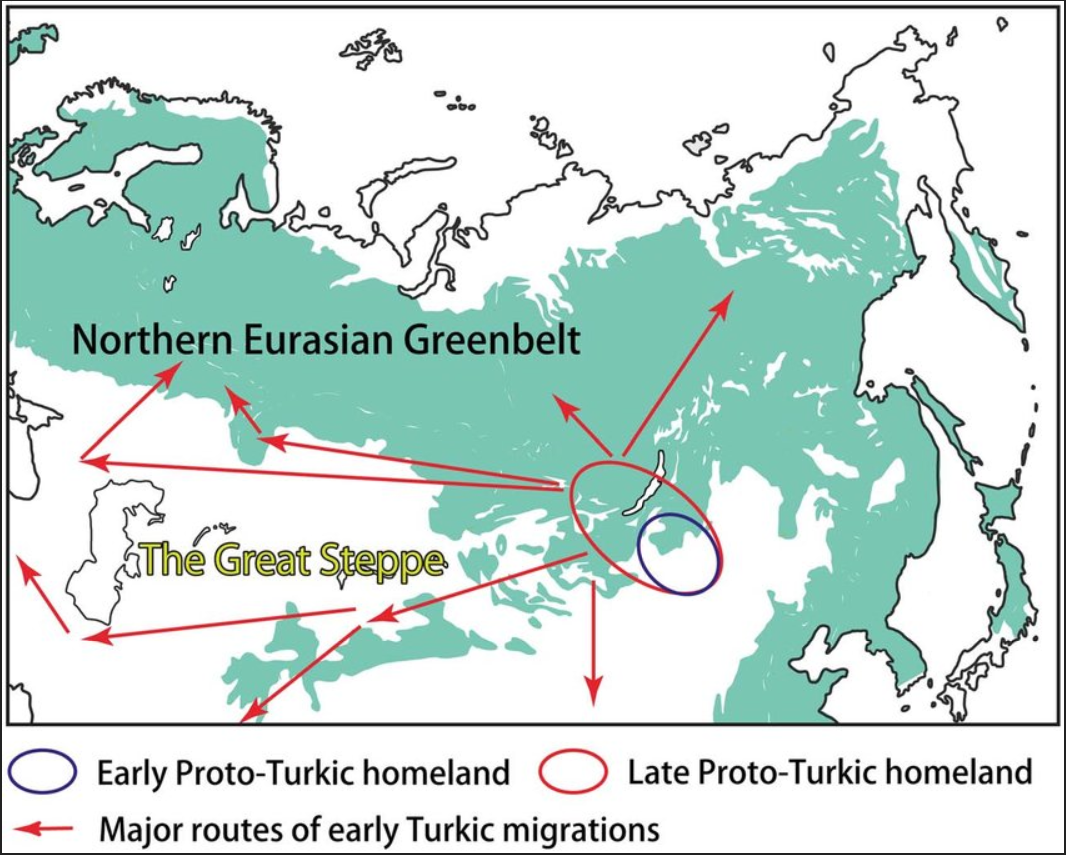

The origins of the Turkic peoples has been a topic of much discussion. Peter Benjamin Golden listed Proto-Turkic lexical items about the climate, topography, flora, fauna, people's modes of subsistence in the hypothetical Proto-Turkic Urheimat and proposed that the Proto-Turkic Urheimat was located at the southern Altai-Sayan region in Siberia. A possible genealogical link of the Turkic languages to Mongolic and Tungusic languages, specifically a hypothetical homeland in Manchuria, such as proposed in the Altaic languages, Transeurasian hypothesis, by Martine Robbeets, has been received support but also criticism, with opponents attributing similarities to long-term contact. Linguistic and genetic evidence strongly suggest an early presence of Turkic peoples in Mongolia. The proto-Turkic-speakers may have been linked to Neolithic East Asian people, East Asian agricultural societies in Northeastern China, which is to be associated with the Xinglongwa culture and the succeeding Hongshan culture, based on varying degrees of specific Northeast Asian genetic substratum among modern Turkic speakers. The East Asian agricultural roots of the Proto-Turkic language have been corroborated in multiple recent studies. According to historians, "the Proto-Turkic subsistence strategy included an agricultural component, a tradition that ultimately went back to the origin of millet agriculture in Northeast China". Around 2,200 BC, the agricultural ancestors of the Turkic peoples probably migrated westwards into Mongolia, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle, in part borrowed from Iranian peoples. Given nomadic peoples such as Xiongnu, Rouran Khaganate, Rouran and Xianbei share underlying genetic ancestry "that falls into or close to the northeast Asian gene pool", the proto-Turkic language likely originated in northeastern Asia.

A 2018 Autosome, autosomal Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single-nucleotide polymorphism study suggested that Eurasian Steppe slowly transitioned from Indo European and Iranian languages, Iranian-speaking groups with largely western Eurasian ancestry to increasing East Asian ancestry with Turkic and Mongolian groups in the past 4000 years, including extensive Turkic migrations out of Mongolia and slow assimilation of local populations.

Genetic data shows that the different Central Asian Turkic-speaking peoples have between 22% to 60% East Asian ancestry (samplified by "Baikal hunter-gatherer ancestry" shared with other Northeast Asians and Eastern Siberians), in contrast to Iranian-speaking Central Asians, specifically Tajiks, which display genetic continuity to Indo-Iranians of the Iron Age. Certain Turkic ethnic groups, specifically the Kazakhs, display even higher East Asian ancestry. This is explained by substantial Mongolic peoples, Mongolian influence on the Kazakhs, Kazakh genome, through significant admixture between medieval Turkic Kipchaks with medieval Mongolians. The data suggests that the Mongol invasion of Central Asia had lasting impacts onto the genetic makeup of Kazakhs.Estimating the impact of the Mongol expansion upon the gene pool of Central Asians. ЛД Дамба · 2018

A 2018 Autosome, autosomal Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single-nucleotide polymorphism study suggested that Eurasian Steppe slowly transitioned from Indo European and Iranian languages, Iranian-speaking groups with largely western Eurasian ancestry to increasing East Asian ancestry with Turkic and Mongolian groups in the past 4000 years, including extensive Turkic migrations out of Mongolia and slow assimilation of local populations.

Genetic data shows that the different Central Asian Turkic-speaking peoples have between 22% to 60% East Asian ancestry (samplified by "Baikal hunter-gatherer ancestry" shared with other Northeast Asians and Eastern Siberians), in contrast to Iranian-speaking Central Asians, specifically Tajiks, which display genetic continuity to Indo-Iranians of the Iron Age. Certain Turkic ethnic groups, specifically the Kazakhs, display even higher East Asian ancestry. This is explained by substantial Mongolic peoples, Mongolian influence on the Kazakhs, Kazakh genome, through significant admixture between medieval Turkic Kipchaks with medieval Mongolians. The data suggests that the Mongol invasion of Central Asia had lasting impacts onto the genetic makeup of Kazakhs.Estimating the impact of the Mongol expansion upon the gene pool of Central Asians. ЛД Дамба · 2018

Early historical attestation

The earliest separate Turkic peoples, such as the ''Gekun'' (鬲昆) and ''Xinli'' (薪犁), appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BCESima Qian ''Records of the Grand Historian'

The earliest separate Turkic peoples, such as the ''Gekun'' (鬲昆) and ''Xinli'' (薪犁), appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BCESima Qian ''Records of the Grand Historian'Vol. 110

"後北服渾庾、屈射、丁零、鬲昆、薪犁之國。於是匈奴貴人大臣皆服,以冒頓單于爲賢。" tr. "Later [he went] north [and] subjugated the nations of Hunyu, Qushe, Dingling, Gekun, and Xinli. Therefore, the Xiongnu nobles and dignitaries all admired [and] regarded Modun chanyu as capable" (contemporaneous with the Chinese Han Dynasty)Findley (2005), p. 29. and later among the Turkic-speaking Tiele people, Tiele as ''Yenisei Kyrgyz, Hegu'' (紇骨)Pulleyblank, E. G. "The Name of the Kirghiz." Central Asiatic Journal 34, no. 1/2 (1990). p. 99 and ''Xueyantuo, Xue'' (薛). The Tiele people, Tiele (also known as Gaoche 高車, lit. "High Carts"), may be related to the Xiongnu and the Dingling. According to the ''Book of Wei'', the Tiele people were the remnants of the Chidi (赤狄), the red Beidi, Di people competing with the Jin (Chinese state), Jin in the Spring and Autumn period. Historically they were established after the 6th century BCE.Peter Zieme: The Old Turkish Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Empire of the Mongols. Special tape for Exhibition 2005/2006, p. 64 The Tiele were first mentioned in Chinese literature from the 6th to 8th centuries. Some scholars (Haneda, Onogawa, Geng, etc.) proposed that ''Tiele'', ''Dili'', ''Dingling'', ''Chile'', ''Tele'', & ''Tujue'' all transliterated underlying ''Türk''; however, Peter Benjamin Golden, Golden proposed that ''Dili'', ''Dingling'', ''Chile'', ''Tele'', & ''Tiele'' transliterated ''Tegrek'' while Tujue transliterated ''Türküt'', plural of ''Türk''. The appellation ''Türük'' (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰) ~ ''Türk'' (OT: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚) (whence Middle Chinese 突厥 *''dwət-kuɑt'' > *''tɦut-kyat'' > standard Chinese: ''Tūjué'') was initially reserved exclusively for the Göktürks by Chinese, Tibetans, and even the Turkic-speaking Uyghur Khaganate, Uyghurs. In contrast, medieval Muslim writers, including Turkic speakers like Ottoman historian Mustafa Âlî and explorer Evliya Çelebi as well as Timurid Empire, Timurid scientist Ulugh Beg, often viewed Inner Asian tribes, "as forming a single entity regardless of their linguistic affiliation" commonly used Turk as a generic name for Inner Asians (whether Turkic- or Mongolic-speaking). Only in modern era do modern historians use Turks to refer to all peoples speaking Turkic languages, differentiated from non-Turkic speakers. According to some researchers (Duan, Xue, Tang, Lung, Onogawa, etc.) the later Ashina tribe descended from the Tiele people, Tiele confederation. The Tiele however were probably one of many early Turkic groups, ancestral to later Turkic populations. However, according to Lee & Kuang (2017), Chinese histories do not describe the Ashina and the Göktürks as descending from the Dingling or the Tiele confederation.

Xiongnu (3rd c. BCE – 1st c. CE)

It has even been suggested that the Xiongnu themselves, who were mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic language, Proto-Turkic speakers. Although little is known for certain about the Xiongnu language(s), it seems likely that at least a considerable part of Xiongnu tribes spoke a Turkic language. Some scholars believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups. A genetic research in 2003, of the remains of 62 individuals buried between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD at the Xiongnu necropolis at Egyin Gol in northern Mongolia, found that these individuals have similar DNA sequences as many modern Turkic groups, supporting the view that the Xiongnu were at least partially of Turkic origin. These examined individuals were found to be primarily of East Asia, East Asian ancestry.

Using the only extant possibly Xiongnu writings, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helan Mountains, some scholars argue that the older Xiongnu writings are precursors to the earliest known Old Turkic, Turkic alphabet, the Orkhon script. Petroglyphs of this region dates from the 9th millennium BCE to the 19th century, and consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and few painted images. Excavations done during 1924–1925 in Noin-Ula kurgans located in the Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulaanbaatar produced objects with over 20 carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.

It has even been suggested that the Xiongnu themselves, who were mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic language, Proto-Turkic speakers. Although little is known for certain about the Xiongnu language(s), it seems likely that at least a considerable part of Xiongnu tribes spoke a Turkic language. Some scholars believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups. A genetic research in 2003, of the remains of 62 individuals buried between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD at the Xiongnu necropolis at Egyin Gol in northern Mongolia, found that these individuals have similar DNA sequences as many modern Turkic groups, supporting the view that the Xiongnu were at least partially of Turkic origin. These examined individuals were found to be primarily of East Asia, East Asian ancestry.

Using the only extant possibly Xiongnu writings, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helan Mountains, some scholars argue that the older Xiongnu writings are precursors to the earliest known Old Turkic, Turkic alphabet, the Orkhon script. Petroglyphs of this region dates from the 9th millennium BCE to the 19th century, and consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and few painted images. Excavations done during 1924–1925 in Noin-Ula kurgans located in the Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulaanbaatar produced objects with over 20 carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.

Huns (4th–6th c. CE)

In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC. The Hun hordes ruled by Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century, might have been, at least partially, Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.G. Pulleyblank, "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese: Part II", Asia Major n.s. 9 (1963) 206–65 Since Guignes' time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. The issue remains controversial. Their relationship to other peoples known collectively as the Iranian Huns is generally accepted, but whether these groups are all inter-related remains controversial.

Some scholars claimed Huns as Proto-Mongols, Proto-Mongolian or Yeniseian people, Yeniseian in origin. Linguistic studies by Otto Maenchen-Helfen and others have suggested that the Hunnic language, language used by the Huns in Europe was too little documented to be classified. Nevertheless, the majority of the proper names used by Huns appear to be Turkic in origin, though they are "far from unambiguous, so no firm conclusion can be drawn from this type of data".

In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC. The Hun hordes ruled by Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century, might have been, at least partially, Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.G. Pulleyblank, "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese: Part II", Asia Major n.s. 9 (1963) 206–65 Since Guignes' time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. The issue remains controversial. Their relationship to other peoples known collectively as the Iranian Huns is generally accepted, but whether these groups are all inter-related remains controversial.

Some scholars claimed Huns as Proto-Mongols, Proto-Mongolian or Yeniseian people, Yeniseian in origin. Linguistic studies by Otto Maenchen-Helfen and others have suggested that the Hunnic language, language used by the Huns in Europe was too little documented to be classified. Nevertheless, the majority of the proper names used by Huns appear to be Turkic in origin, though they are "far from unambiguous, so no firm conclusion can be drawn from this type of data".

Steppe expansions

Göktürks – Turkic Khaganate (5th–8th c.)

The earliest certain mentioning of the politonym "Turk" was in the Chinese Book of Zhou. In the 540s AD, this text mentions that the Turks came to China's border seeking silk goods and a trade relationship. A Sogdian diplomat represented China in a series of embassies between the Western Wei dynasty and the Turks in the years 545 and 546.

According to the ''Book of Sui'' and the ''Tongdian'', they were "mixed barbarians" (; ''záhú'') who migrated from Pingliang (now in modern Gansu province, China) to the Rourans seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from the prevailing dynasty. Wei Zheng et al., ''Suishu''

The earliest certain mentioning of the politonym "Turk" was in the Chinese Book of Zhou. In the 540s AD, this text mentions that the Turks came to China's border seeking silk goods and a trade relationship. A Sogdian diplomat represented China in a series of embassies between the Western Wei dynasty and the Turks in the years 545 and 546.

According to the ''Book of Sui'' and the ''Tongdian'', they were "mixed barbarians" (; ''záhú'') who migrated from Pingliang (now in modern Gansu province, China) to the Rourans seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from the prevailing dynasty. Wei Zheng et al., ''Suishu''vol. 84

quote: "突厥之先,平涼雜胡也,姓阿史那氏。後魏太武滅沮渠氏,阿史那以五百家奔茹茹,世居金山,工於鐵作。金山狀如兜鍪,俗呼兜鍪為「突厥」,因以為號。"Du You, ''Tongdian'

vol. 197

quote: "突厥之先,平涼今平涼郡雜胡也,蓋匈奴之別種,姓阿史那氏。後魏太武滅沮渠氏,沮渠茂虔都姑臧,謂之北涼,為魏所滅。阿史那以五百家奔蠕蠕,代居金山,狀如兜鍪,俗呼兜鍪為「突厥」,因以為號。" Alternatively, according to the ''Book of Zhou'', ''History of the Northern Dynasties'', and ''New Book of Tang'', the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation.Linghu Defen et al., ''Zhoushu''

vol. 50

quote: "突厥者,蓋匈奴之別種,姓阿史那氏。" Göktürks were also posited as having originated from an obscure Suo state (索國), north of the Xiongnu. The Ashina tribe were famed metalsmiths and were granted land south of the Altai Mountains (金山 ''Jinshan''), which looked like a helmet, from which they were said to have gotten their name 突厥 (''Tūjué''), the first recorded use of "Turk" as a political name. In the 6th-century, Ashina's power had increased such that they conquered the Tiele on their Rouran overlords' behalf and even overthrew Rourans and established the First Turkic Khaganate.

The original Old Turkic name ''Kök Türk'' derives from ''kök'' ~ ''kö:k'', "sky, sky-coloured, blue, blue-grey". Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khaganate had its temporary Khagans from the Ashina tribe, Ashina clan, who were ''subordinate'' to a sovereignty, sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khanate, Khaganate retained elements of its original Animism, animistic- Shamanism, shamanistic religion, that later evolved into Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khaganate was also the first state known as "Turk". It eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but many states and peoples later used the name "Turk".

The Göktürks (First Turkic Kaganate) quickly spread west to the Caspian Sea. Between 581 and 603 the Western Turkic Khaganate in Kazakhstan separated from the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in Mongolia and Manchuria during a civil war. The Han-Chinese successfully overthrew the Eastern Turks in 630 and created a military Protectorate until 682. After that time the Second Turkic Khaganate ruled large parts of the former Göktürk area. After several wars between Turks, Chinese and Tibetans, the weakened Second Turkic Khaganate was replaced by the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 744.Haywood, John (1998), ''Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492'', Barnes & Noble

The original Old Turkic name ''Kök Türk'' derives from ''kök'' ~ ''kö:k'', "sky, sky-coloured, blue, blue-grey". Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khaganate had its temporary Khagans from the Ashina tribe, Ashina clan, who were ''subordinate'' to a sovereignty, sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khanate, Khaganate retained elements of its original Animism, animistic- Shamanism, shamanistic religion, that later evolved into Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khaganate was also the first state known as "Turk". It eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but many states and peoples later used the name "Turk".

The Göktürks (First Turkic Kaganate) quickly spread west to the Caspian Sea. Between 581 and 603 the Western Turkic Khaganate in Kazakhstan separated from the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in Mongolia and Manchuria during a civil war. The Han-Chinese successfully overthrew the Eastern Turks in 630 and created a military Protectorate until 682. After that time the Second Turkic Khaganate ruled large parts of the former Göktürk area. After several wars between Turks, Chinese and Tibetans, the weakened Second Turkic Khaganate was replaced by the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 744.Haywood, John (1998), ''Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492'', Barnes & Noble

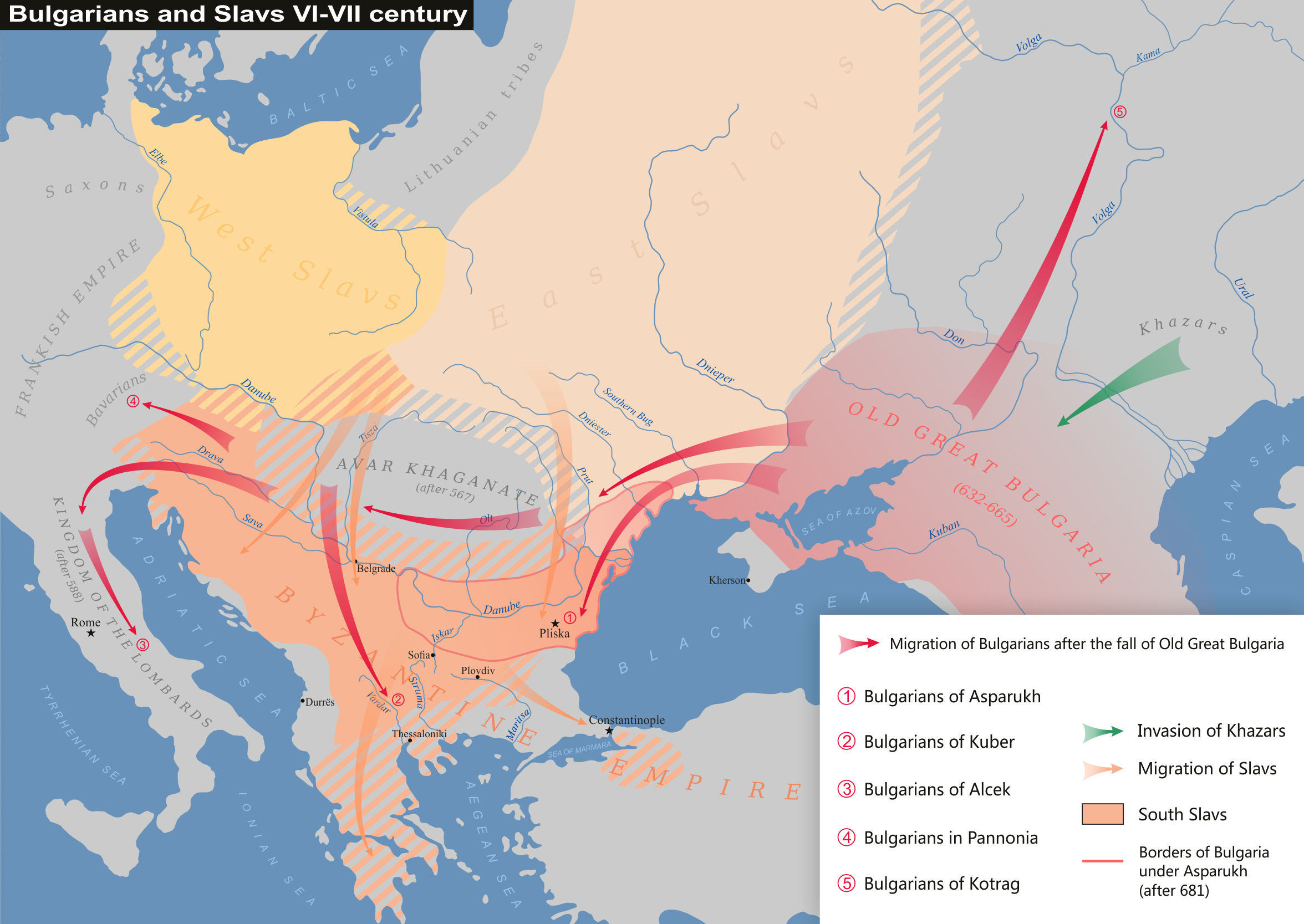

Bulgars, Golden Horde and the Siberian Khanate

The Bulgars established themselves in between the Caspian and Black Seas in the 5th and 6th centuries, followed by their conquerors, the Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th or 9th century. After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks. One group of Bulgars settled in the Volga region and mixed with local Volga Finns to become the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan. These Bulgars were conquered by the Mongols following their westward sweep under Ogedei Khan in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Southeastern Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and mixed with the Slavs, Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.

The Bulgars established themselves in between the Caspian and Black Seas in the 5th and 6th centuries, followed by their conquerors, the Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th or 9th century. After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks. One group of Bulgars settled in the Volga region and mixed with local Volga Finns to become the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan. These Bulgars were conquered by the Mongols following their westward sweep under Ogedei Khan in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Southeastern Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and mixed with the Slavs, Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.

The Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 922 and influenced the region as it controlled many trade routes. In the 13th century, Mongols invaded Europe and established the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, western & northern Central Asia, and even western Siberia. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation and Islamic Volga Bulgaria were absorbed by the Golden Horde in the 13th century; in the 14th century, Islam became the official religion under Uzbeg Khan where the general population (Turks) as well as the aristocracy (Mongols) came to speak the Kipchak language and were collectively known as "Tatars" by Russians and Westerners. This country was also known as the Kipchak Khanate and covered most of what is today Ukraine, as well as the entirety of modern-day southern and eastern Russia (the European section). The Golden Horde disintegrated into several khanates and hordes in the 15th and 16th century including the Crimean Khanate, Khanate of Kazan, and Kazakh Khanate (among others), which were one by one conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th through 19th centuries.

In Siberia, the Siberian Khanate was established in the 1490s by fleeing Tatar aristocrats of the disintegrating Golden Horde who established Islam as the official religion in western Siberia over the partly Islamized native Siberian Tatars and indigenous Uralic peoples. It was the northernmost Islamic state in recorded history and it survived up until 1598 when it was conquered by Russia.

The Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 922 and influenced the region as it controlled many trade routes. In the 13th century, Mongols invaded Europe and established the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, western & northern Central Asia, and even western Siberia. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation and Islamic Volga Bulgaria were absorbed by the Golden Horde in the 13th century; in the 14th century, Islam became the official religion under Uzbeg Khan where the general population (Turks) as well as the aristocracy (Mongols) came to speak the Kipchak language and were collectively known as "Tatars" by Russians and Westerners. This country was also known as the Kipchak Khanate and covered most of what is today Ukraine, as well as the entirety of modern-day southern and eastern Russia (the European section). The Golden Horde disintegrated into several khanates and hordes in the 15th and 16th century including the Crimean Khanate, Khanate of Kazan, and Kazakh Khanate (among others), which were one by one conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th through 19th centuries.

In Siberia, the Siberian Khanate was established in the 1490s by fleeing Tatar aristocrats of the disintegrating Golden Horde who established Islam as the official religion in western Siberia over the partly Islamized native Siberian Tatars and indigenous Uralic peoples. It was the northernmost Islamic state in recorded history and it survived up until 1598 when it was conquered by Russia.

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th c.)

The Uyghur Khaganate had established itself by the year 744 AD. Through trade relations established with China, its capital city of Ordu Baliq in central Mongolia's Orkhon Valley became a wealthy center of commerce, and a significant portion of the Uyghur population abandoned their nomadic lifestyle for a sedentary one. The Uyghur Khaganate produced extensive literature, and a relatively high number of its inhabitants were literate.

The official state religion of the early Uyghur Khaganate was Manichaeism, which was introduced through the conversion of Bögü Qaghan by the Sogdians after the An Lushan rebellion. The Uyghur Khaganate was tolerant of religious diversity and practiced variety of religions including Buddhism, Christianity, shamanism and Manichaeism.

During the same time period, the Shatuo Turks emerged as power factor in Northern and Central China and were recognized by the Tang Empire as allied power.

The Uyghur Khaganate had established itself by the year 744 AD. Through trade relations established with China, its capital city of Ordu Baliq in central Mongolia's Orkhon Valley became a wealthy center of commerce, and a significant portion of the Uyghur population abandoned their nomadic lifestyle for a sedentary one. The Uyghur Khaganate produced extensive literature, and a relatively high number of its inhabitants were literate.

The official state religion of the early Uyghur Khaganate was Manichaeism, which was introduced through the conversion of Bögü Qaghan by the Sogdians after the An Lushan rebellion. The Uyghur Khaganate was tolerant of religious diversity and practiced variety of religions including Buddhism, Christianity, shamanism and Manichaeism.

During the same time period, the Shatuo Turks emerged as power factor in Northern and Central China and were recognized by the Tang Empire as allied power.

The Shatuo Turks had founded several short-lived sinicized dynasties in northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The official language of these dynasties was Chinese and they used Chinese titles and names. Some Shaotuo Turks emperors also claimed patrilineal Han Chinese ancestry.According to ''Old History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:舊五代史/卷99, vol. 99, and ''New History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:新五代史/卷10, vol. 10. Liu Zhiyuan was of Shatuo origin. According to ''Wudai Huiyao''

The Shatuo Turks had founded several short-lived sinicized dynasties in northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The official language of these dynasties was Chinese and they used Chinese titles and names. Some Shaotuo Turks emperors also claimed patrilineal Han Chinese ancestry.According to ''Old History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:舊五代史/卷99, vol. 99, and ''New History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:新五代史/卷10, vol. 10. Liu Zhiyuan was of Shatuo origin. According to ''Wudai Huiyao''vol. 1

Liu Zhiyuan's great-great-grandfather Liu Tuan (劉湍) (titled as Emperor Mingyuan posthumously, granted the temple name of Wenzu) descended from Liu Bing (劉昞), Prince of Kingdom of Huaiyang, Huaiyang, a son of Emperor Ming of HanAccording to ''Old History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:舊五代史/卷99, vol. 99, and ''New History of the Five Dynasties'', :zh:s:新五代史/卷10, vol. 10. Liu Zhiyuan was of Shatuo origin. According to ''Wudai Huiyao''

vol. 1

Liu Zhiyuan's great-great-grandfather Liu Tuan (劉湍) (titled as Emperor Mingyuan posthumously, granted the temple name of Wenzu) descended from Liu Bing (劉昞), Prince of Huaiyang, a son of Emperor Ming of Han After the fall of the Tang-Dynasty in 907, the Shatuo Turks replaced them and created the Later Tang Dynasty in 923. The Shatuo Turks ruled over a large part of northern China, including Beijing. They adopted Chinese names and united Turkic and Chinese traditions. Later Tang fell in 937 but the Shatuo rose to become one of the most powerful clans of China. They created several other dynasies, including the Later Jin (Five Dynasties), Later Jin and Later Han (Five Dynasties), Later Han. The Shatuo Turks were later assimilated into the Han Chinese ethnic group after they were conquered by the Song dynasty. The Yenisei Kyrgyz allied with China to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 840 AD. From the Yenisei River, the Kyrgyz pushed south and eastward in to Xinjiang and the Orkhon Valley in central Mongolia, leaving much of the Uyghur civilization in ruins. Much of the Uyghur population relocated to the south in modern-day China, establishing kingdoms in Gansu and Turpan.

Central Asia

Kangar union (659–750)

The Kangar Union (''Qanghar Odaghu'') was a Turkic people, Turkic state in the former territory of the Western Turkic Khaganate (the entire present-day state of Kazakhstan, without Zhetysu). The capital of the Kangar union was located in the Ulytau mountains. Among the Pechenegs, the Kangar formed the elite of the Pecheneg tribes. After being defeated by the Kipchaks, Oghuz Turks, and the Khazars, they migrated west and defeated Magyars, and after forming an alliance with the Bulgars, they defeated the Byzantine Army. The Pecheneg state was established by the 11th century and at its peak carried a population of over 2.5 million, composed of many different ethnic groups.

The elite of the Kangar tribes are believed to have had an Indo-Iranians, Iranian origin, and they likely spoke an Iranian langauge, while most of the Pecheneg population spoke a Turkic language, with a significant percentage speaking Hunno-Bulgar languages, Hunno-Bulgar dialects.

The Yatuks, a tribe within the Kangar state who could not accompany the Kangars as they migrated West, remained in the old lands, where they are known as the Kangly people, who are now part of the Uzbeks, Uzbek, Kazakhs, Kazakh, and Karakalpaks, Karakalpak tribes.

The Kangar Union (''Qanghar Odaghu'') was a Turkic people, Turkic state in the former territory of the Western Turkic Khaganate (the entire present-day state of Kazakhstan, without Zhetysu). The capital of the Kangar union was located in the Ulytau mountains. Among the Pechenegs, the Kangar formed the elite of the Pecheneg tribes. After being defeated by the Kipchaks, Oghuz Turks, and the Khazars, they migrated west and defeated Magyars, and after forming an alliance with the Bulgars, they defeated the Byzantine Army. The Pecheneg state was established by the 11th century and at its peak carried a population of over 2.5 million, composed of many different ethnic groups.

The elite of the Kangar tribes are believed to have had an Indo-Iranians, Iranian origin, and they likely spoke an Iranian langauge, while most of the Pecheneg population spoke a Turkic language, with a significant percentage speaking Hunno-Bulgar languages, Hunno-Bulgar dialects.

The Yatuks, a tribe within the Kangar state who could not accompany the Kangars as they migrated West, remained in the old lands, where they are known as the Kangly people, who are now part of the Uzbeks, Uzbek, Kazakhs, Kazakh, and Karakalpaks, Karakalpak tribes.

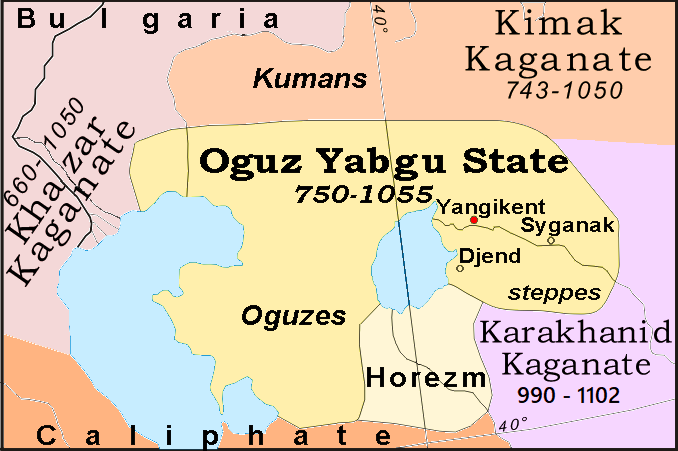

Oghuz Yabgu State (766–1055)

The Oguz Yabgu State (''Oguz il'', meaning "Oguz Land,", "Oguz Country")(750–1055) was a Turkic people, Turkic state, founded by Oghuz Turks in 766, located geographically in an area between the coasts of the Caspian Sea, Caspian and Aral Seas. Oguz tribes occupied a vast territory in Kazakhstan along the Irgiz River (Kazakhstan), Irgiz, Yaik, Emba River, Emba, and Uil River, Uil rivers, the Aral Sea area, the Syr Darya valley, the foothills of the Karatau Mountains in Tian Shan, Tien-Shan, and the Chui River valley (see map). The Oguz political association developed in the 9th and 10th centuries in the Syr Darya basin.

The Oguz Yabgu State (''Oguz il'', meaning "Oguz Land,", "Oguz Country")(750–1055) was a Turkic people, Turkic state, founded by Oghuz Turks in 766, located geographically in an area between the coasts of the Caspian Sea, Caspian and Aral Seas. Oguz tribes occupied a vast territory in Kazakhstan along the Irgiz River (Kazakhstan), Irgiz, Yaik, Emba River, Emba, and Uil River, Uil rivers, the Aral Sea area, the Syr Darya valley, the foothills of the Karatau Mountains in Tian Shan, Tien-Shan, and the Chui River valley (see map). The Oguz political association developed in the 9th and 10th centuries in the Syr Darya basin.

Iranian, Indian, Arabic, and Anatolian expansion

Turkic peoples and related groups migrated west from present-day Northeastern China, Mongolia, Siberia and the Turkestan-region towards the Iranian plateau, South Asia, and Anatolia (modern Turkey) in many waves. The date of the initial expansion remains unknown.Persia

= Ghaznavid dynasty (977–1186)

="Ghaznavid Dynasty"

Online Edition 2007 Although the dynasty was of Central Asian Turkic origin, it was thoroughly Persianised in terms of language, culture, literature and habits and hence is regarded by some as a "Persian dynasty".

= Seljuk Empire (1037–1194)

== Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

= The Timurid Empire was a Turko-Mongol empire founded in the late 14th century through military conquests led by Timurlane. The establishment of a cosmopolitan empire was followed by the Timurid Renaissance, a period of local enrichment in mathematics, astronomy, architecture, as well as newfound economic growth. The cultural progress of the Timurid period ended as soon as the empire collapsed in the early 16th century, leaving many intellecuals and artists to turn elsewhere in search of employment.

The Timurid Empire was a Turko-Mongol empire founded in the late 14th century through military conquests led by Timurlane. The establishment of a cosmopolitan empire was followed by the Timurid Renaissance, a period of local enrichment in mathematics, astronomy, architecture, as well as newfound economic growth. The cultural progress of the Timurid period ended as soon as the empire collapsed in the early 16th century, leaving many intellecuals and artists to turn elsewhere in search of employment.

= Central Asian khanates (1501–1920)

== Safavid dynasty (1501–1736)

= The Safavid dynasty of Persia (1501–1736) were of mixed ancestry (Kurdish people, Kurdish ''Encyclopædia Iranica'' and Azerbaijani people, Azeri Turks,"Peoples of Iran"''Encyclopædia Iranica''. RN Frye. which included intermarriages with Georgians, Georgian, Circassians, Circassian, and Pontic Greeks, Pontic GreekAnthony Bryer. "Greeks and Türkmens: The Pontic Exception", ''Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 29'' (1975), Appendix II "Genealogy of the Muslim Marriages of the Princesses of Trebizond" dignitaries). Through intermarriage and other political considerations, the Safavids spoke Persian and Turkish, and some of the Shahs composed poems in their native Turkish language. Concurrently, the Shahs themselves also supported Persian literature, poetry and art projects including the grand Shahnama of Tahmasp I, Shah Tahmasp.Ira Marvin Lapidus, ''A history of Islamic Societies'', Cambridge University Press, 2002, 2nd edition. pg 445. The Safavid dynasty ruled parts of Greater Iran for more than two centuries. and established the Twelver school of Imamah (Shi'a Twelver doctrine), Shi'a IslamRM Savory, ''Safavids'', ''Encyclopedia of Islam'', 2nd ed. as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning points in Muslim history

= Afsharid dynasty (1736–1796)

= The Afsharid dynasty was named after the Turkic Afshar tribe to which they belonged. The Afshars had migrated from Turkestan to Azerbaijan in the 13th century. The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the military commander Nader Shah who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself King of Iran. Nader belonged to the Qereqlu branch of the Afshars. During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sassanid Empire.= Qajar dynasty (1789–1925)

= The Qajar dynasty was created by the Turkic Qajars (tribe), Qajar tribe, ruling over Iran from 1789 to 1925.Abbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3. The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease, putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty, and Mohammad Khan was formally crowned as Shah after his Battle of Krtsanisi, punitive campaign against Iran's Georgian subjects.Michael Axworthy''Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day''

Penguin UK, 6 November 2008. In the Caucasus, the Qajar dynasty permanently lost many of Iran's integral areas to the Imperial Russia, Russians over the course of the 19th century, comprising modern-day Georgia (country), Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan and Armenia.Timothy C. Dowling

''Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond''

pp 728–730 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014 The dynasty was founded by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar and continued until Ahmad Shah Qajar.

South Asia

The Delhi Sultanate is a term used to cover five short-lived, Delhi-based kingdoms three of which were of Turkic origin in medieval India. These Turkic dynasties were the Mamluk dynasty (Delhi), Mamluk dynasty (1206–90); the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320); and the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414). Southern India also saw many Turkic origin dynasties like the Adil Shahi dynasty, the Bidar Sultanate, and the Qutb Shahi dynasty, collectively known as the Deccan sultanates. The Mughal Empire was a Turko-Mongol founded Indian empire that, at its greatest territorial extent, ruled most of South Asia, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and parts of Uzbekistan from the early 16th to the early 18th centuries. The Mughal dynasty was founded by a Chagatai Khanate, Chagatai Turkic prince named Babur (reigned 1526–30), who was descended from the Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) on his father's side and from Chagatai, second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother's side.Encyclopædia Britannica ArticlMughal Dynasty

/ref> A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state. and the Last Turkic dynasty in India were the Hyderabad State lasted from 1724 to 1948 located in the south-central region of India.

Arab world

The Arab Muslim Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyads and Abbasids fought against the pagan Turks in the Türgesh Khaganate in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasids, Abbasid Caliphate, caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the 10th century. Examples of regional de-facto independent states include the short lived Tulunids and Ikhshidid dynasty, Ikhshidids in Egypt. The Oghuz Turks, Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk Turks, Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

The Arab Muslim Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyads and Abbasids fought against the pagan Turks in the Türgesh Khaganate in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasids, Abbasid Caliphate, caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the 10th century. Examples of regional de-facto independent states include the short lived Tulunids and Ikhshidid dynasty, Ikhshidids in Egypt. The Oghuz Turks, Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk Turks, Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

Anatolia – Ottomans

After many battles, the western Oghuz Turks established their own state and later constructed the Ottoman Empire. The main migration of the Oghuz Turks occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East.Carter V. Findley, ''The Turks in World History'' (Oxford University Press, October 2004) They also took part in the military encounters of the Crusades. In 1090–91, the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army. As the Seljuk Empire declined following the Mongol invasions, Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire emerged as the new important Turkic state, that came to dominate not only the Middle East, but even southeastern Europe, parts of southwestern Russia, and northern Africa.Islamization

Turkic peoples like the Karluks (mainly 8th century), Uyghur_Khaganate#Successors, Uyghurs, Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz, Turkmens, and Kipchaks later came into contact with Muslims, and most of them gradually adopted Islam. Some groups of Turkic people practice other religions, including their original animistic-shamanistic religion, Christianity, Burkhanism, Jews (Khazars, Krymchaks, Crimean Karaites), Buddhism and a small number of Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrians.Modern history

Physiognomy

According to historians Joo-Yup Lee and Shuntu Kuang, Chinese official histories do not depict Turkic peoples as belonging to a single uniform entity called "Turks". However "Chinese histories also depict the Turkic-speaking peoples as typically possessing East/Inner Asian physiognomy, as well as occasionally having West Eurasian physiognomy." According to "fragmentary information on the Xiongnu language that can be found in the Chinese histories, the Xiongnu were Turkic," however historians have been unable to confirm whether or not they were Turkic. Sima Qian's description of their legendary origins suggest their physiognomy was "not too different from that of... Han (漢) Chinese population," but a subset of Xiongnu known as the Jie people were described having "deep-set eyes," "high nose bridges" and "heavy facial hair." The Jie may have been Yeniseian people, Yeniseian, although others maintaining an Iranian peoples, Iranian affiliation, and regardless of whether or not the Xiongnu were Turkic, they were a hybrid people. According to the ''Old Book of Tang'', Ashina Simo "was not given a high military post by the Ashina rulers because of his Sogdian (''huren'' 胡人) physiognomy." The Tang dynasty, Tang historian Yan Shigu described the Hu people of his day as "blue-eyed and red bearded" descendants of the Wusun, whereas "no comparable depiction of the Kök Türks or Tiele is found in the official Chinese histories." Historian Peter Benjamin Golden, Peter Golden has reported that genetic testing of the proposed descendants of the Ashina tribe does seem to confirm a link to the Indo-Iranians, emphasizing that "''the Turks as a whole ‘were made up of heterogeneous and somatically dissimilar populations". Historian :tr:Emel Esin, Emel Esin and Professor Xue Zongzheng have argued that West Eurasian features were typical of the royal Ashina tribe, Ashina clan of the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and that their appearance shifted to an East Asian one due to intermarriage with foreign nobility. As a result, by the time of Bust of Kul Tigin, Kul Tigin (684 AD), members of the Ashina dynasty had East Asian features. "The Chinese sources of the Kök-Türk period describe the turcophone Kirgiz with green eyes and red hair. They must have been in majority Europeoids although intermarriages with the Chinese had begun long ago. The Kök-Türk kagan Mu-kan was also depicted with blue eyes and an elongated ruddy face. Probably as a result of the repeated marriages, the members of the Kök-Türk dynasty (pl. XLVII/a), and particularly Köl Tigin, had frankly Mongoloid features. Perhaps in the hope of finding an occasion to claim rulership over China, or because the high birth of the mother warranted seniority, the Inner Asian monarchs sought alliances165 with dynasties reigning in China." Lee and Kuang believe it is likely "early and medieval Turkic peoples themselves did not form a homogeneous entity and that some of them, non-Turkic by origin, had become Turkicised at some point in history." They also suggest that many modern Turkic-speaking populations are not directly descended from early Turkic peoples. Lee and Kuang concluded that "both medieval Chinese histories and modern DNA studies point to the fact that the early and medieval Turkic peoples were made up of heterogeneous and somatically dissimilar populations." Like Chinese historians, Medieval Muslim writers generally depicted the Turks as having an East Asian appearance. Unlike Chinese historians, Medieval Muslim writers used the term "Turk" broadly to refer to not only Turkic-speaking peoples but also various non-Turkic speaking peoples, such as the Hephthalites, Rus' people, Rus, Hungarians, Magyars, and Tibetans. In the 13th century, Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani, Juzjani referred to the people of Tibet and the mountains between Tibet and Bengal as "Turks" and "people with Turkish features." Medieval Arab and Persian descriptions of Turks state that they looked strange from their perspective and were extremely physically different from Arabs. Turks were described as "broad faced people with small eyes", having light-colored, often reddish hair, and with pink skin,: "One of the issues that most occupied the travelers was the physiognomy of the Turks.120 Both mentally and physically, Turks appeared to the Arab authors as very different from themselves.121 The shape of these "broad faced people with small eyes" and their physique impressed the travelers crossing the Eurasian lands." "According to this explanation: Because of the Turks' distance from the course of the sun and from the sun's rising and descending, the snow in their lands is abundant and coldness and humidity dominate it. This caused the bodies of this land's inhabitants to become mellow and their epidermis thick.124 Their sleek hair is spare and its colour is pale with an inclination to red. Due to the cold weather of their surroundings, coldness dominates their temper. In effect, the cold climate breeds abundant flesh. The arctic temperature compresses the heat and makes it visible. This gives them their pink skin. It is noticeable among the people who have bulky bodies and pale colour. Whilst a chilly wind hits them, their faces, lips, fingers and legs became red. This is because while they were warm their blood expanded, and then the cold temperature caused it to amass." as being "short, with small eyes, nostrils, and mouths" (Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi), as being "full-faced with small eyes" (Al-Tabari), as possessing "a large head (''sar-i buzurg''), a broad face (''rūy-i pahn''), narrow eyes (''chashmhā-i tang''), and a flat nose (''bīnī-i pakhch''), and unpleasing lips and teeth (''lab va dandān na nīkū'')" (Keikavus).Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 207-208 of 197–239 Quote: "The Chinese histories also depict the Turkic-speaking peoples as typically possessing East/Inner Asian physiognomy, as well as occasionally having West Eurasian physiognomy. DNA studies corroborate such characterisation of the Turkic peoples." On Western Turkic Khaganate, Western Turkic coins "the faces of the governor and governess are clearly Mongoloid (a roundish face, narrow eyes), and the portrait have definite old Türk features (long hair, absence of headdress of the governor, a tricorn headdress of the governess)". In the Ghaznavids' residential palace of Lashkari Bazar, there survives a partially conserved portrait depicting a turbaned and haloed adolescent figure with full cheeks, slanted eyes, and a small, sinuous mouth. The Armenian historian Movses Kaghankatvatsi describes the Turks of the Western Turkic Khaganate as "broad-faced, without eyelashes, and with long flowing hair like women". Al-Masudi writes that the Oghuz Turks in Yengi-kent near the mouth of the Syr Darya "are distinguished from other Turks by their valour, their slanted eyes, and the smallness of their stature." Later Muslim writers noted a change in the physiognomy of Oghuz Turks. According to Rashid al-Din Hamadani, "because of the climate their features gradually changed into those of Tajiks. Since they were not Tajiks, the Tajik peoples called them ''turkmān'', i.e. Turk-like (''Turk-mānand'')." Ḥāfiẓ Tanīsh Mīr Muḥammad Bukhārī also related that the Oghuz' ‘Turkic face did not remain as it was’ after their migration into Transoxiana and Iran. Khanate of Khiva, Khiva khan Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur wrote in his Chagatai language treatise ''Shajara-i Tarākima'' (Genealogy of the Turkmens) that "their chin started to become narrow, their eyes started to become large, their faces started to become small, and their noses started to become big’ after five or six generations". Ottoman historian Mustafa Âlî commented in ''Künhüʾl-aḫbār'' that Anatolian Turks and Ottoman elites are ethnically mixed: "Most of the inhabitants of Rûm are of confused ethnic origin. Among its notables there are few whose lineage does not go back to a convert to Islam." Kevin Alan Brook states that like "most nomadic Turks, the Western Turkic Khazars were racially and ethnically mixed." Istakhri described Khazars as having black hair while Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi described them as having blue eyes, light skin, and reddish hair. Istakhri mentions that there were "Black Khazars" and "White Khazars." Most scholars believe these were political designations: black being lower class while white being higher class. Constantin Zuckerman argues that these "had physical and racial differences and explained that they stemmed from the merger of the Khazars with the Barsils." Old East Slavic sources called the Khazars the "White Ugry" and the Magyars the "Black Ugry." Soviet excavated Khazar remains show Slavic-type, European-type, and a minority Mongoloid-type skulls. The Yenisei Kyrgyz are mentioned in the ''New Book of Tang'' as having the same script and language as the Uyghur Khaganate, Uyghurs but "The people are all tall and big and have red hair, white faces, and green eyes." The ''New Book of Tang'' also states that the neighboring Boma tribe resembled the Kyrgyz but their language was different, which may imply the Kyrgyz were originally a non-Turkic people, who were later Turkicized through inter-tribal marriages. According to Lee & Kuang, the prevalence of West Eurasian features among the ancient Kirghiz was likely due to their genetic relation to Indo-Iranians. According to Gardizi, the Kyrgyz were mixed with "Saqlabs" (Slavs), which explains the red hair and white skin among the Kyrgyz, while the ''New Book'' states that the Kyrgyz "intermixed with the Dingling." The Kyrgyz "regarded those with black eyes as descending from [Li] Ling," a Han dynasty general who defected to the Xiongnu. In a Chinese legal statute from the early period of the Ming dynasty, the Kipchaks are described as having blond hair and blue eyes. It also states that they had a "vile" and "peculiar" appearance, and that some Chinese people wouldn't want to marry them. Russian anthropologist Oshanin (1964: 24, 32) notes that "the ‘Mongoloid’ phenotype, characteristic of modern Kazakhs and Qirghiz, prevails among the skulls of the Qipchaq and Pecheneg nomads found in the kurgans in eastern Ukraine"; Lee & Kuang (2017) propose that Oshanin's discovery is explainable by assuming that the historical Kipchaks' modern descendants are Kazakhs of the Zhuz#Junior zhuz, Lesser Horde, whose men possess a high frequency of haplogroup C2's subclade C2b1b1 (59.7 to 78%). Lee and Kuang also suggest that the high frequency (63.9%) of the Y-DNA haplogroup R-M73 among Karakypshaks (a tribe within the Kipchaks) allows inferrence about the genetics of Karakypshaks' medieval ancestors, thus explaining why some medieval Kipchaks were described as possessing "blue [or green] eyes and red hair.Remarks

Archaeology

* Xinglongwa culture * Hongshan culture * :ru:Чаатас, Čaatas culture * :ru:Аскизская культура, Askiz culture * Kurumchi culture * Saltovo-Mayaki * Saymaluu-Tash * Bilär * Por-Bazhyn * Ordu-Baliq * JankentInternational organizations

TÜRKSOY

Türksoy carries out activities to strengthen cultural ties between Turkic peoples. One of the main goals to transmit their common cultural heritage to future generations and promote it around the world. Every year, one city in the Turkic world is selected as the "Cultural Capital of the Turkic World". Within the framework of events to celebrate the Cultural Capital of the Turkic World, numerous cultural events are held, gathering artists, scholars and intellectuals, giving them the opportunity to exchange their experiences, as well as promoting the city in question internationally.Organization of Turkic States

The Organization of Turkic States, founded on November 3, 2009 by the ''Nakhchivan Agreement'' confederation, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey, aims to integrate these organizations into a tighter geopolitical framework. The member countries are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and Uzbekistan. The idea of setting up this cooperative council was first put forward by Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev back in 2006. Hungary has announced to be interested in joining the Organization of Turkic States. Since August 2018, Hungary has official observer status in the Organization of Turkic States. Turkmenistan also joined as an observer state to the organization at 8th summit. Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus was admitted to the organization as observer member at the 2022 Organization of Turkic States summit, 2022 Samarkand Summit.Demographics

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Southern Europe. the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkey and Iran. Additionally, Turkic people are found within Crimea, Altishahr region of western China, northern Iraq, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and former Yugoslavia.

A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland. There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchaks, Kipchak, Karluks, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash people, Chuvash, and Sakha language, Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.

The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.

Historical population:

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups' core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Southern Europe. the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkey and Iran. Additionally, Turkic people are found within Crimea, Altishahr region of western China, northern Iraq, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and former Yugoslavia.

A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland. There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchaks, Kipchak, Karluks, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash people, Chuvash, and Sakha language, Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.

The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.

Historical population:

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups' core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

Cuisine

Markets in the steppe region had a limited range of foodstuffs available—mostly grains, dried fruits, spices, and tea. Turks mostly herded sheep, goats and horses. Dairy was a staple of the nomadic diet and there are many Turkic words for various dairy products such as ''süt'' (milk), ''yagh'' (butter), ayran, ''kaymak, qaymaq'' (similar to clotted cream), Kumis, qi̅mi̅z (fermented mare's milk) and ''qurut'' (dried yoghurt). During the Middle Ages Kazakh cuisine, Kazakh, Kyrgyz people, Kyrgyz and Tatar cuisine, Tatars, who were historically part of the Turkic nomadic group known as the Golden Horde, continued to develop new variations of dairy products. Nomadic Turks cooked their meals in a ''Kazan (cookware), qazan'', a pot similar to a cauldron; a wooden rack called a ''qasqan'' can be used to prepare certain steamed foods, like the traditional meat dumplings called ''Manti (food), manti''. They also used a ''saj'', a griddle that was traditionally placed on stones over a fire, and ''skewer, shish''. In later times, the Persian tava was borrowed from the Persians for frying, but traditionally nomadic Turks did most of their cooking using the qazan, saj and shish. Meals were served in a bowl, called a ''chanaq'', and eaten with a knife (''bïchaq'') and spoon (''qashi̅q''). Both bowl and spoon were historically made from wood. Other traditional utensils used in food preparation included a thin rolling pin called ''oqlaghu'', a colander called ''süzgu̅çh'', and a grinding stone called ''tāgirmān''. Medieval grain dishes included preparations of whole grains, soups, porridges, breads and pastries. Fried or toasted whole grains were called ''qawïrmach'', while ''köchä'' was crushed grain that was cooked with dairy products. ''Salma'' were broad noodles that could be served with boiled or roasted meat; cut noodles were called ''tutmaj'' in the Middle Ages and are called ''kesme'' today. There are many types of bread doughs in Turkic cuisine. ''Saj bread, Yupqa'' is the thinnest type of dough, ''Bawirsaq, bawi̅rsaq'' is a type of fried bread dough, and ''Shelpek, chälpäk'' is a deep fried flat bread. ''Qatlama'' is a fried bread that may be sprinkled with dried fruit or meat, rolled, and sliced like pinwheel sandwiches. ''Toqach'' and ''chöräk'' are varieties of bread, and Börek, böräk is a type of filled pie pastry. Herd animals were usually slaughtered during the winter months and various types of sausages were prepared to preserve the meats, including a type of sausage called ''sujuk''. Though prohibited by halal, Islamic dietary restrictions, historically Turkic nomads also had a variety of blood sausage. One type of sausage, called ''Qazı, qazi̅'', was made from horsemeat and another variety was filled with a mixture of ground meat, offal and rice. Chopped meat was called ''qïyma'' and spit-roasted meat was ''söklünch''—from the root ''sök-'' meaning "to tear off", the latter dish is known as kebab in modern times. ''Kavurma, Qawirma'' is a typical fried meat dish, and ''kullama'' is a soup of noodles and lamb.Religion

Early Turkic mythology and Tengrism

Early Turkic mythology was dominated by Shamanism in Central Asia, Shamanism, Animism and Tengrism. The Turkic animistic traditions were mostly focused on ancestor worship, Polytheism, polytheistic-animism and shamanism. Later this animistic tradition would form the more organized Tengrism. The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763.

The gray wolf, wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Ashina tribe, Ashina is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse and bird of prey, predatory birds, such as the eagle or falcon, are also main figures of Turkic mythology.

Early Turkic mythology was dominated by Shamanism in Central Asia, Shamanism, Animism and Tengrism. The Turkic animistic traditions were mostly focused on ancestor worship, Polytheism, polytheistic-animism and shamanism. Later this animistic tradition would form the more organized Tengrism. The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763.

The gray wolf, wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Ashina tribe, Ashina is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse and bird of prey, predatory birds, such as the eagle or falcon, are also main figures of Turkic mythology.

Religious conversions

Buddhism

Buddhism played an important role in the history of Turkic peoples, with the first Turkic state adopting and supporting the spread of Buddhism being the Turkic Shahis and the Göktürks. The Göktürks syncretized Buddhism with their traditional religion Tengrism and also incorporated elements of the Iranian traditional religions, such as Zoroastrianism. Buddhism had it's hight among the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region. Buddhism had also considerable impact and influence onto various other historical Turkic groups. In pre-Islamic times, Buddhism and Tengrism coexisted, with several Buddhist temples, monasteries, figures and steles, with images of Buddhist characters and sceneries, were constructed by various Turkic tribes. Throughout Kazakhstan, there exist various historical Buddhist sites, including an underground Buddhist cave monastery. After the Arab expansion, Arab conquest of Central Asia, and the spread of Islam among locals, Buddhism (and Tengrism) started to lose ground, however a certain influence of the Buddhist teachings remained during the next centuries. Tengri Bögü Khan initially made the now extinct Manichaeism the state religion of the Uyghur Khaganate in 763 and it was also popular among the Karluks. It was gradually replaced by the Mahayana Buddhism. It existed in the Buddhist Uyghur Gaochang up to the 12th century. Tibetan Buddhism, or Vajrayana was the main religion after Manichaeism. They worshipped Buddha, Täŋri Täŋrisi Burxan, Guanyin, Quanšï Im Pusar and Maitreya, Maitri Burxan. Turkic Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent and west Xinjiang attributed with a rapid and almost total disappearance of it and other religions in North India and Central Asia. The Yugur, Sari Uygurs "Yellow Yughurs" of Western China, as well as the Tuvans of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples.Islam

Most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism. Azeris are traditionally Shiite Muslims. Religious observance is less stricter in the Republic of Azerbaijan compared to Iranian Azerbaijan.Christianity

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash people, Chuvash of Chuvash Republic, Chuvashia and the Gagauz people, Gagauz (''Gökoğuz'') of Moldova, the vast majority of Chuvash people, Chuvash and the Gagauz people, Gagauz are Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christians. The traditional religion of the Chuvash people, Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam.

The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans. It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period. It disappeared after its collapse.

Kryashens are a sub-group of the Volga Tatars, and the vast majority are Russian Orthodoxy, Orthodox Christians. Nağaybäk are an indigenous Turkic people in Russia, most Nağaybäk are Christian and were largely converted during the 18th century. Many Volga Tatars were Christianized by Ivan IV of Russia, Ivan the Terrible during the 16th century, and continued to Christianized under subsequent Russian rulers and Orthodox clergy up to the mid-eighteenth century.

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash people, Chuvash of Chuvash Republic, Chuvashia and the Gagauz people, Gagauz (''Gökoğuz'') of Moldova, the vast majority of Chuvash people, Chuvash and the Gagauz people, Gagauz are Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christians. The traditional religion of the Chuvash people, Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam.

The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans. It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period. It disappeared after its collapse.

Kryashens are a sub-group of the Volga Tatars, and the vast majority are Russian Orthodoxy, Orthodox Christians. Nağaybäk are an indigenous Turkic people in Russia, most Nağaybäk are Christian and were largely converted during the 18th century. Many Volga Tatars were Christianized by Ivan IV of Russia, Ivan the Terrible during the 16th century, and continued to Christianized under subsequent Russian rulers and Orthodox clergy up to the mid-eighteenth century.

Animism

Today there are several groups that support a revival of the ancient traditions. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many in Central Asia converted or openly practice animistic and shamanistic rituals. It is estimated that about 60% of Kyrgyz people practice a form of animistic rituals. In Kazakhstan there are about 54,000 followers of the ancient traditions.Muslim Turks and non-Muslim Turks

The Uyghur Turks, who once belonged to a variety of religions, were gradually Islamized during a period spanning the 10th and 13th centuries. Some scholars have linked the phenomenon of recently Islamized Uyghur soldiers recruited by the Mongol Empire to the slow conversion of Uyghur populations to Islam.

The non-Muslim Turks' worship of Tengri and other gods was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them – ''The Infidels – May God destroy them!''

The Basmil, Yabāḳu and Uyghur states were among the Turkic peoples who fought against the Kara-Khanids spread of Islam. The Islamic Kara-Khanids were made out of Tukhsi, Yaghma, Çiğil and Karluk.

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu. The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.

Mahmud al-Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as "Uighur dogs" and called them "Tats", which referred to the "Uighur infidels" according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat". While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan (meaning Buddha, acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.

The Uyghur Turks, who once belonged to a variety of religions, were gradually Islamized during a period spanning the 10th and 13th centuries. Some scholars have linked the phenomenon of recently Islamized Uyghur soldiers recruited by the Mongol Empire to the slow conversion of Uyghur populations to Islam.