Sydney Silverman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Sydney Silverman (8 October 1895 – 9 February 1968) was a British Labour politician and vocal opponent of

Silverman was prominent in his support for

Silverman was prominent in his support for

Sidney Silverman & the Death Penalty - UK Parliament Living Heritage

{{DEFAULTSORT:Silverman, Sydney 1895 births 1968 deaths Alumni of the University of Liverpool British anti–death penalty activists Academic personnel of the University of Helsinki English people of Romanian-Jewish descent Councillors in Liverpool English Jews Jewish British politicians Jewish pacifists Jewish socialists Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Lawyers from Liverpool People educated at Liverpool Institute High School for Boys UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs 1945–1950 UK MPs 1950–1951 UK MPs 1951–1955 UK MPs 1955–1959 UK MPs 1959–1964 UK MPs 1964–1966 UK MPs 1966–1970 English solicitors Academics of the University of Liverpool

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

.

Early life

Silverman was born in poverty to a migrant Jewish parents from Jassy, Romania. His father was adraper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period, ...

living in the Kensington Fields area of Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

.

Silverman attended Liverpool Institute and the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

, thanks to scholarships. During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he was a conscientious objector to military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job ( volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Some nations (e.g., Mexico) require ...

and served three prison sentences, in Preston, Wormwood Scrubs

Wormwood Scrubs, known locally as The Scrubs (or simply Scrubs), is an open space in Old Oak Common located in the north-eastern corner of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in west London. It is the largest open space in the borough, ...

and Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

prisons.

Career

Silverman was a lecturer in English at the NationalUniversity of Finland

The University of Helsinki ( fi, Helsingin yliopisto, sv, Helsingfors universitet, abbreviated UH) is a public research university located in Helsinki, Finland since 1829, but founded in the city of Turku (in Swedish ''Åbo'') in 1640 as the ...

from 1921 to 1925, and then returned to the University of Liverpool to teach and read law. After qualifying as a solicitor, he worked on workmen's compensation claims and landlord-tenant disputes.

From 1932 to 1938, Silverman served on Liverpool City Council. He contested Liverpool Exchange without success at a by-election in 1933, but was elected as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for Nelson and Colne

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

in the general election in 1935.

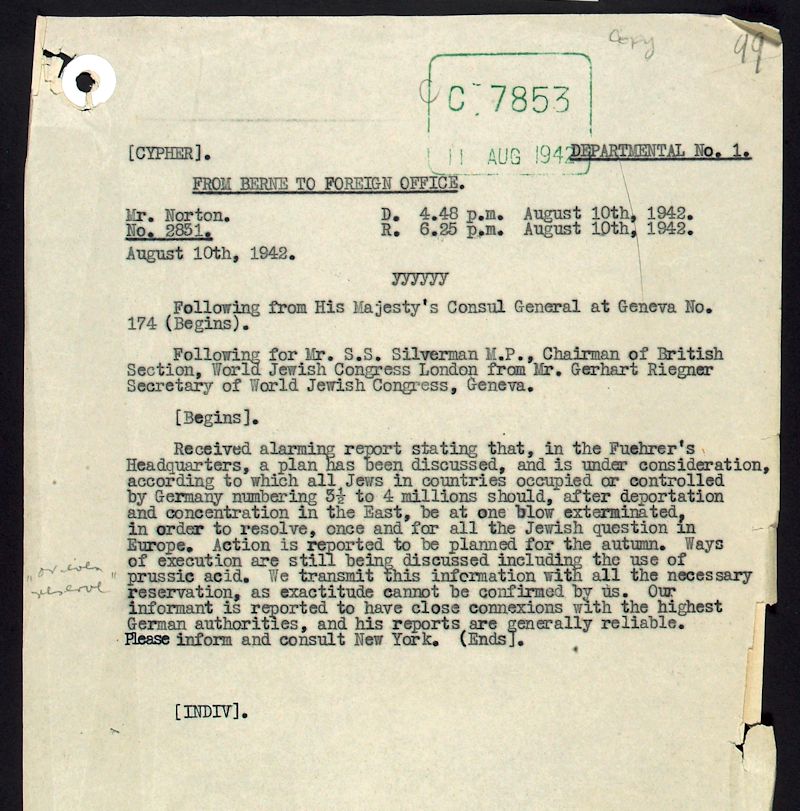

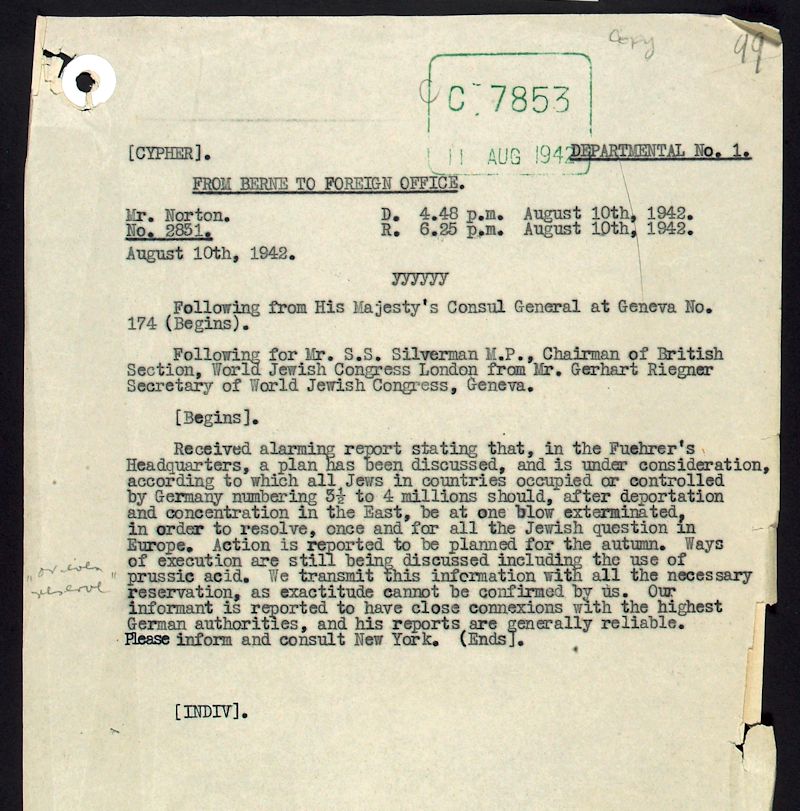

Silverman was prominent in his support for

Silverman was prominent in his support for Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s worldwide and for their rights in Palestine. He rethought his pacifism in light of the reports of antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, and reluctantly supported Britain's entry into the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. He was vocal in asking from the government (and Churchill in particular) for a statement of war aims, which had become a contentious issue in the early years of the war. Silverman was prominent within the debates over the potential repatriation of Jewish refugees, telling Churchill "that it would be difficult to conceive of a more cruel procedure than to take people who have lost everything they have – their homes, their relatives, their children, all the things that make life decent and possible – and compel them against their will, to go back to the scene of those crimes".

Silverman was widely expected to join the government after the Labour victory in the general election in 1945, but, as he was a leftist, he was not appointed by Clement Attlee. He became opposed to the government's foreign policy. He refused to support German rearmament in 1954 and had the Labour Party Whip withdrawn from November 1954 to April 1955. He was one of the founders of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nuc ...

. In 1961, as a protest against bipartisan

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing political parties find co ...

support for British nuclear weapons, he voted against the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

estimates in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, and was suspended from the Labour Party Whip from March 1961 until May 1963.

Silverman died on 9 February 1968 following a stroke.

Opponent of capital punishment

A fervent opponent of the death penalty, Silverman founded the National Campaign for the Abolition of Capital Punishment. He wrote about severalmiscarriages of justice

A miscarriage of justice occurs when a grossly unfair outcome occurs in a criminal or civil proceeding, such as the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. Miscarriages are also known as wrongful convictions. Inno ...

in the 1940s and 1950s, such as the hanging of Timothy Evans

Timothy John Evans (20 November 1924 – 9 March 1950) was a Welshman who was wrongly accused of murdering his wife (Beryl) and infant daughter (Geraldine) at their residence in Notting Hill, London. In January 1950, Evans was tried, and was c ...

when it later emerged that serial killer

A serial killer is typically a person who murders three or more persons,A

*

*

*

* with the murders taking place over more than a month and including a significant period of time between them. While most authorities set a threshold of three ...

John Christie had murdered Evans's wife and had given perjured evidence at Evans's trial in 1949. Silverman proposed a private member's bill on abolition of the death penalty, which was passed by 200 votes to 98 on a free vote in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

on 28 June 1956; but was defeated in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

.

In 1965, he successfully piloted the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Bill through Parliament, abolishing capital punishment for murder in the UK and in the British Armed Forces for a period of five years but with provision for abolition to be made permanent by affirmative resolutions of both Houses of Parliament before the end of that period. The appropriate resolutions were passed in 1969. Silverman was opposed at the 1966 general election in the Nelson and Colne constituency by Patrick Downey, the uncle of Lesley Anne Downey, a victim in the Moors murders

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, England. The victims were five children—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, and Edward E ...

case, who stood on an explicitly pro-hanging platform. Downey polled over 5,000 votes, 13.7%, then the largest vote for a genuinely independent candidate since 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. It is also the only year in which Nuclear weapon, nuclear weapons Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have been used in combat.

Events

Below, ...

.

Notes

References

* * * * *Emrys Hughes

Emrys Daniel Hughes (10 July 1894 – 18 October 1969) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, journalist and author. He was Labour MP for South Ayrshire in Scotland from 1946 to 1969. Among his many published books was a biography of his father ...

: ''Sydney Silverman, Rebel in Parliament'', 1969

External links

* *Sidney Silverman & the Death Penalty - UK Parliament Living Heritage

{{DEFAULTSORT:Silverman, Sydney 1895 births 1968 deaths Alumni of the University of Liverpool British anti–death penalty activists Academic personnel of the University of Helsinki English people of Romanian-Jewish descent Councillors in Liverpool English Jews Jewish British politicians Jewish pacifists Jewish socialists Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Lawyers from Liverpool People educated at Liverpool Institute High School for Boys UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs 1945–1950 UK MPs 1950–1951 UK MPs 1951–1955 UK MPs 1955–1959 UK MPs 1959–1964 UK MPs 1964–1966 UK MPs 1966–1970 English solicitors Academics of the University of Liverpool