Syadvada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

( hi, अनेकान्तवाद, "many-sidedness") is the

IEP, Mark Owen Webb, Texas Tech University In the same way, spiritual truths are complex, they have multiple aspects, language cannot express their plurality, yet through effort and appropriate karma they can be experienced. The ''anekāntavāda'' premises of the Jains is ancient, as evidenced by its mention in Buddhist texts such as the ''Samaññaphala Sutta''. The Jain āgamas suggest that Māhavira's approach to answering all metaphysical philosophical questions was a "qualified yes" (''syāt''). These texts identify ''anekāntavāda'' doctrine to be one of the key differences between the teachings of the Māhavira and those of the Buddha. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not" to metaphysical questions. The Māhavira, in contrast, taught his followers to accept both "it is" and "it is not", with "from a viewpoint" qualification and with reconciliation to understand the absolute reality. ''Syādvāda'' (predication

Ancient India, particularly the centuries in which the Mahavira and the Buddha lived, was a ground of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self or soul. Jain view of soul differs from those found in ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts, and Jain view about ''jiva'' and ''ajiva'' (self, matter) utilizes ''anekantavada''.For a complete discussion of ''anekantavada'' on the Jain concept of ''jiva'':

The Upanishadic thought (Hindu) postulated the impermanence of matter and body, but the existence of an unchanging, eternal metaphysical reality of ''

Ancient India, particularly the centuries in which the Mahavira and the Buddha lived, was a ground of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self or soul. Jain view of soul differs from those found in ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts, and Jain view about ''jiva'' and ''ajiva'' (self, matter) utilizes ''anekantavada''.For a complete discussion of ''anekantavada'' on the Jain concept of ''jiva'':

The Upanishadic thought (Hindu) postulated the impermanence of matter and body, but the existence of an unchanging, eternal metaphysical reality of ''

Encyclopaedia Britannica According to Upadhyaye, the ''Bhagvatisūtra'' (also called Vyākhyāprajñapti) mentions three primary predications of the ''saptibhaṅgīnaya''.Upadhyaye, A. N. (2001) pp. 6136–37 This too is a Svetambara text, and considered by Digambara Jains as unauthentic. The earliest comprehensive teachings of anekāntavāda doctrine is found in the ''

The Jain texts explain the ''anekāntvāda'' concept using the parable of

The Jain texts explain the ''anekāntvāda'' concept using the parable of

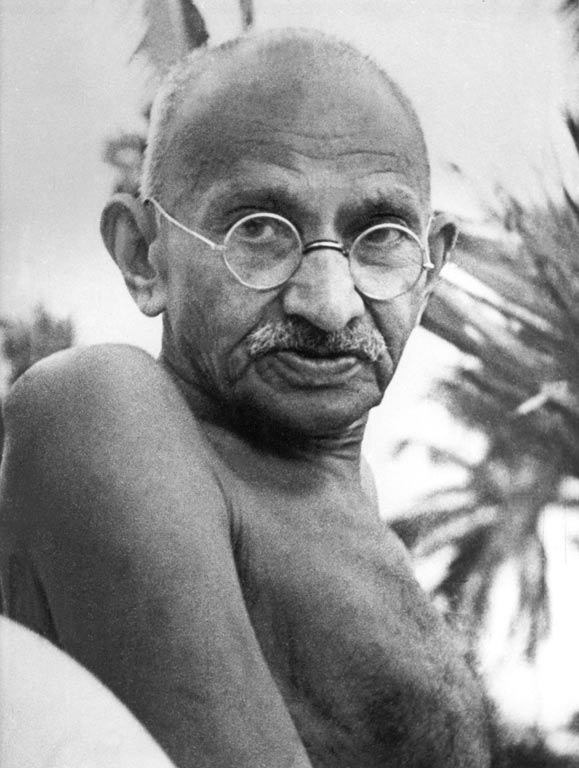

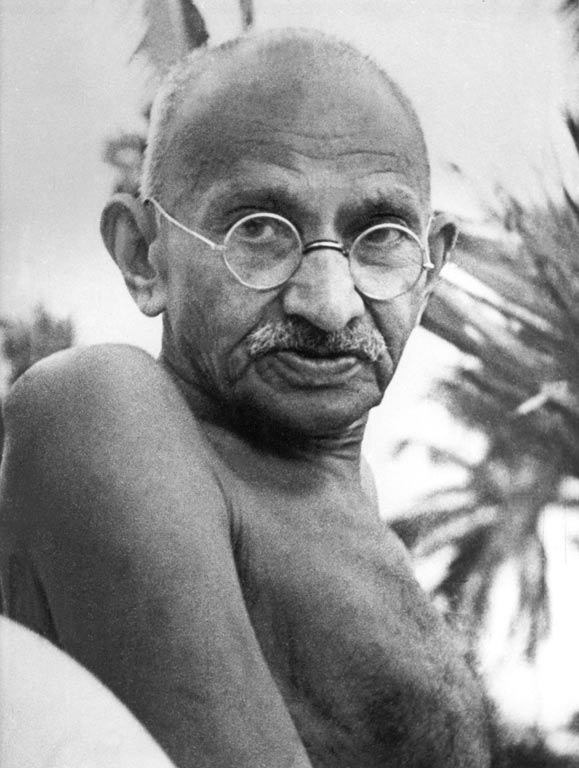

Mahatma Gandhi mentioned Anekantavada and Syadvada in the journal ''

Mahatma Gandhi mentioned Anekantavada and Syadvada in the journal ''

Jain

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

doctrine about metaphysical truths that emerged in ancient India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

. It states that the ultimate truth and reality is complex and has multiple aspects.

According to Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

, no single, specific statement can describe the nature of existence and the absolute truth

In philosophy, universality or absolutism is the idea that universal facts exist and can be progressively discovered, as opposed to relativism, which asserts that all facts are merely relative to one's perspective. Absolutism and relativism have ...

. This knowledge ('' Kevala Jnana''), it adds, is comprehended only by the Arihants. Other beings and their statements about absolute truth are incomplete, and at best a partial truth. All knowledge claims, according to the ''anekāntavāda'' doctrine must be qualified in many ways, including being affirmed and denied. Anekāntavāda is a fundamental doctrine of Jainism.

The origins of ''anekāntavāda '' can be traced back to the teachings of Mahāvīra (599–527 BCE), the 24th Jain . The dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

al concepts of ''syādvāda'' "conditioned viewpoints" and ''nayavāda'' "partial viewpoints" arose from ''anekāntavāda'' in the medieval era, providing Jainism with more detailed logical structure and expression. The details of the doctrine emerged in Jainism in the 1st millennium CE, from debates between scholars of Jain, Buddhist and vedic schools of philosophies.

Anekantavada has also been interpreted to mean non-absolutism, "intellectual Ahimsa", religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and tolerating the religious diversity of a society or coun ...

, as well as a rejection of fanaticism that leads to terror attacks and mass violence. Some scholars state that modern revisionism has attempted to reinterpret anekantavada with religious tolerance, openmindedness and pluralism..The word may be literally translated as “non-one-sidedness doctrine,” or “the doctrine of not-one-side.”

Etymology

The word ''anekāntavāda'' is a compound of twoSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

words: ''anekānta'' and ''vāda''. The word ''anekānta'' itself is composed of three root words, "an" (not), "eka" (one) and "anta" (end, side), together it connotes "not one ended, sided", "many-sidedness", or "manifoldness".Grimes, John (1996) p. 34 The word ''vāda'' means "doctrine, way, speak, thesis". The term ''anekāntavāda'' is translated by scholars as the doctrine of "many-sidedness", "non-onesidedness", or "many pointedness".

The term ''anekāntavāda'' is not found in early texts considered canonical by Svetambara tradition of Jainism. However, traces of the doctrines are found in comments of Mahavira in these Svetambara texts, where he states that the finite and infinite depends on one's perspective. The word anekantavada was coined by Acharya Siddhasen Divakar to denote the teachings of Mahavira that state truth can be expressed in infinite ways. The earliest comprehensive teachings of anekāntavāda doctrine is found in the ''Tattvarthasutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature '' ''artha">nowiki/>''artha''.html" ;"title="artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ...

'' by Acharya Umaswami, and is considered to be authoritative by all Jain sects. In the Digambara

''Digambara'' (; "sky-clad") is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being '' Śvētāmbara'' (white-clad). The Sanskrit word ''Digambara'' means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing ...

tradition texts, the 'two-truths theory' of Kundakunda also provides the core of this doctrine.

Philosophical overview

In fact, the Jain doctrine of anekantavada emerges to be a social attempt at equality and respect to all diverse views and ideologies through the philosophical elucidation of the truth or reality. The idea of reality gets enrichment in Jainism as it proposes that the reality cannot be the one and ultimate, it can have multi-dimensional form. So, what is reality for one individual may not be the reality for others. Anekantavada brings forth a synthesis, a happy blend and proposes that reality has many forms as seen by various individuals and all must respect the reality perceived by one-another. This is the way the society can progress and this is the way to resolve conflicts and to aim at peace in society. The Jain doctrine of ''anekāntavāda'', also known as ''anekāntatva'', states that truth and reality is complex and always has multiple aspects. Reality can be experienced, but it is not possible to totally express it with language. Human attempts to communicate is ''naya'', or "partial expression of the truth". Language is not Truth, but a means and attempt to express truth. From truth, according to Māhavira, language returns and not the other way around. One can experience the truth of a taste, but cannot fully express that taste through language. Any attempts to express the experience is ''syāt'', or valid "in some respect" but it still remains a "perhaps, just one perspective, incomplete".Jain philosophyIEP, Mark Owen Webb, Texas Tech University In the same way, spiritual truths are complex, they have multiple aspects, language cannot express their plurality, yet through effort and appropriate karma they can be experienced. The ''anekāntavāda'' premises of the Jains is ancient, as evidenced by its mention in Buddhist texts such as the ''Samaññaphala Sutta''. The Jain āgamas suggest that Māhavira's approach to answering all metaphysical philosophical questions was a "qualified yes" (''syāt''). These texts identify ''anekāntavāda'' doctrine to be one of the key differences between the teachings of the Māhavira and those of the Buddha. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not" to metaphysical questions. The Māhavira, in contrast, taught his followers to accept both "it is" and "it is not", with "from a viewpoint" qualification and with reconciliation to understand the absolute reality. ''Syādvāda'' (predication

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

) and ''Nayavāda'' (perspective epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epi ...

) of Jainism expand on the concept of ''anekāntavāda''. ''Syādvāda'' recommends the expression of ''anekānta'' by prefixing the epithet ''syād'' to every phrase or expression describing the nature of existence.

The Jain doctrine of ''anekāntavāda'', according to Bimal Matilal, states that "no philosophic or metaphysical proposition can be true if it is asserted without any condition or limitation". For a metaphysical proposition to be true, according to Jainism, it must include one or more conditions (''syadvada'') or limitations (''nayavada'', standpoints).

Syādvāda

''Syādvāda'' ( sa, स्याद्वाद) is the theory of ''conditioned predication'', the first part of which is derived from the Sanskrit word ''syāt'' ( sa, स्यात्), which is the third person singular of the optative tense of the Sanskrit verb ''as'' ( sa, अस्), 'to be', and which becomes ''syād'' when followed by a vowel or a voiced consonant, in accordance with ''sandhi''. The optative tense in Sanskrit (formerly known as the 'potential') has the same meaning as the present tense of the subjunctive mood in most Indo-European languages, including Hindi, Latin, Russian, French, etc. It is used when there is uncertainty in a statement; not 'it is', but 'it may be', 'one might', etc. The subjunctive is very commonly used in Hindi, for example, in 'kya kahun?', 'what to say?'. The subjunctive is also commonly used in conditional constructions; for example, one of the few English locutions in the subjunctive which remains more or less current is 'were it ०, then ०', or, more commonly, 'if it were..', where 'were' is in the past tense of the subjunctive. Syat can be translated into English as meaning "perchance, may be, perhaps" (it is). The use of the verb 'as' in the optative tense is found in the more ancient Vedic era literature in a similar sense. For example, sutra 1.4.96 of Panini's Astadhyayi explains it as signifying "a chance, maybe, probable". In Jainism, however, ''syadvada'' and ''anekanta'' is not a theory of uncertainty, doubt or relative probabilities. Rather, it is "conditional yes or conditional approval" of any proposition, state Matilal and other scholars. This usage has historic precedents in classical Sanskrit literature, and particularly in other ancient Indian religions (Buddhism and Hinduism) with the phrase , meaning "let it be so, but", or "an answer that is 'neither yes nor no', provisionally accepting an opponent's viewpoint for a certain premise". This would be expressed in archaic English with the subjunctive: 'be it so', a direct translation of . Traditionally, this debate methodology was used by Indian scholars to acknowledge the opponent's viewpoint, but disarm and bound its applicability to certain context and persuade the opponent of aspects not considered. According to Charitrapragya, in Jain context ''syadvada'' does not mean a doctrine of doubt or skepticism, rather it means "multiplicity or multiple possibilities". ''Syat'' in Jainism connotes something different from what the term means in Buddhism and Hinduism. In Jainism, it does not connote an answer that is "neither yes nor no", but it connotes a "many sidedness" to any proposition with a sevenfold predication. ''Syādvāda'' is a theory of qualified predication, states Koller. It states that all knowledge claims must be qualified in many ways, because reality is many-sided. It is done so systematically in later Jain texts through ''saptibhaṅgīnaya'' or " the theory of sevenfold scheme". These ''saptibhaṅgī'' seem to be have been first formulated in Jainism by the 5th or 6th century CE Svetambara scholar Mallavadin, and they are:Grimes, John (1996) p. 312 #Affirmation: ''syād-asti''—in some ways, it is, #Denial: ''syān-nāsti''—in some ways, it is not, #Joint but successive affirmation and denial: ''syād-asti-nāsti''—in some ways, it is, and it is not, #Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: '—in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable, #Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: '—in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable, #Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: '—in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable, #Joint and simultaneous affirmation and denial: '—in some ways, it is indescribable. Each of these seven predicates state the Jain viewpoint of a multifaceted reality from the perspective of time, space, substance and mode. The phrase ''syāt'' declares the standpoint of expression – affirmation with regard to own substance ('' dravya''), place (''kṣetra''), time (''kāla''), and being (''bhāva''), and negation with regard to other substance (''dravya''), place (kṣetra), time (kāla), and being (''bhāva''). Thus, for a ‘jar’, in regard to substance (''dravya'') – earthen, it simply is; wooden, it simply is not. In regard to place (''kṣetra'') – room, it simply is; terrace, it simply is not. In regard to time (''kāla'') – summer, it simply is; winter, it simply is not. In regard to being (''bhāva'') – brown, it simply is; white, it simply is not. And the word ‘simply’ has been inserted for the purpose of excluding a sense not approved by the ‘nuance’; for avoidance of a meaning not intended. According to Samantabhadra's text ''Āptamīmāṁsā'' (Verse 105), "''Syādvāda'', the doctrine of conditional predications, and ''kevalajñāna'' (omniscience), are both illuminators of the substances of reality. The difference between the two is that while ''kevalajñāna'' illumines directly, ''syādvāda'' illumines indirectly". ''Syadvada'' is indispensable and helps establish the truth, according to Samantabhadra.Nayavāda

''Nayavāda'' ( sa, नयवाद) is the theory of standpoints or viewpoints. ''Nayavāda'' is a compound of twoSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

words—''naya'' ("standpoint, viewpoint, interpretation") and ''vāda'' ("doctrine, thesis").Grimes, John (1996) p. 198, 202–03, 274, 301 Nayas are philosophical perspective about a particular topic, and how to make proper conclusions about that topic.

According to Jainism, there are seven ''nayas'' or viewpoints through which one can make complete judgments about absolute reality using ''syadvada''. These seven ''naya'', according to Umaswati, are:

#Naigama-naya: common sense or a universal view

#Samgraha-naya: generic or class view that classifies it

#Vyavahara-naya: pragmatic or a particular view assesses its utility

#Rijusutra-naya: linear view considers it in present time

#Sabda-naya: verbal view that names it

#Samabhirudha-naya: etymological view uses the name and establishes it nature

#Evambhuta-naya: actuality view considers its concrete particulars

The ''naya'' theory emerged after about the 5th century CE, and underwent extensive development in Jainism. There are many variants of ''nayavada'' concept in later Jain texts.

A particular viewpoint is called a ''naya'' or a partial viewpoint. According to Vijay Jain, ''Nayavada'' does not deny the attributes, qualities, modes and other aspects; but qualifies them to be from a particular perspective. A ''naya'' reveals only a part of the totality, and should not be mistaken for the whole. A synthesis of different viewpoints is said to be achieved by the doctrine of conditional predications (''syādvāda'').

Jiva, the changing soul

Ancient India, particularly the centuries in which the Mahavira and the Buddha lived, was a ground of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self or soul. Jain view of soul differs from those found in ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts, and Jain view about ''jiva'' and ''ajiva'' (self, matter) utilizes ''anekantavada''.For a complete discussion of ''anekantavada'' on the Jain concept of ''jiva'':

The Upanishadic thought (Hindu) postulated the impermanence of matter and body, but the existence of an unchanging, eternal metaphysical reality of ''

Ancient India, particularly the centuries in which the Mahavira and the Buddha lived, was a ground of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self or soul. Jain view of soul differs from those found in ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts, and Jain view about ''jiva'' and ''ajiva'' (self, matter) utilizes ''anekantavada''.For a complete discussion of ''anekantavada'' on the Jain concept of ''jiva'':

The Upanishadic thought (Hindu) postulated the impermanence of matter and body, but the existence of an unchanging, eternal metaphysical reality of ''Brahman

In Hinduism, ''Brahman'' ( sa, ब्रह्मन्) connotes the highest universal principle, the ultimate reality in the universe.P. T. Raju (2006), ''Idealistic Thought of India'', Routledge, , page 426 and Conclusion chapter part X ...

'' and '' Ātman'' (soul, self). The Buddhist thought also postulated impermanence, but denied the existence of any unchanging, eternal soul or self and instead posited the concept of anatta (no-self). According to the vedāntin (Upanishadic) conceptual scheme, the Buddhists were wrong in denying permanence and absolutism, and within the Buddhist conceptual scheme, the vedāntins were wrong in denying the reality of impermanence. The two positions were contradictory and mutually exclusive from each other's point of view. The Jains managed a synthesis of the two uncompromising positions with ''anekāntavāda''.; Quote: "To counter the proponents of these diametrically opposed positions uddhist and Hindu Jains developed a position knows as syadvada eeud-VAH-duh the way or path of "perhaps, maybe or somehow." Syadvada states simply that judgments resting on different points of view may differ without any of them being wholly wrong. ..A limited and incomplete judgment is called a naya uh-yuh and all human knowledge is a compilation of nayas, judgments resulting from different attitudes. The Jains were thus able to accept equally the Hindu views of "being" and Buddhist views of "becoming," but took neither in the sense that their partisan advocates desired or found comforting. ..The Jain doctrine of syadvada is non-absolutist and stands firmly against all dogmatisms, even including any assertion that Jainism is the right religious path." Sharma, Arvind (2001) Preface xii From the perspective of a higher, inclusive level made possible by the ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophy, philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, Becoming (philosophy), becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into Category ...

and epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epi ...

of ''anekāntavāda'' and ''syādvāda'', Jains do not see such claims as contradictory or mutually exclusive; instead, they are seen as ''ekantika'' or only partially true. The Jain breadth of vision embraces the perspectives of both Vedānta which, according to Jainism, "recognizes substances but not process", and Buddhism, which "recognizes process but not substance". Jainism, on the other hand, pays equal attention to both substance (''dravya'') and process (''paryaya'').Burch, George (1964) pp. 68–93

This philosophical syncretisation of paradox of change through ''anekānta'' has been acknowledged by modern scholars such as Arvind Sharma, who wrote:

Inclusivist or exclusivist

Some Indian writers state that Anekantavada is an inclusivist doctrine positing that Jainism accepts "non-Jain teachings as partial versions of truth", a form of sectarian tolerance. Others scholars state this is incorrect and a reconstruction of Jain history because Jainism has consistently seen itself in "exclusivist term as the one true path". Classical Jain scholars saw their premises and models of reality as superior than the competing spiritual traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism, both of which Jainism considered inadequate. For instance, the Jain text ''Uttaradhyayana Sutra'' in section 23.63 calls the competing Indian thought to be "heterodox and heretics" and that they "have chosen a wrong path, the right path is that taught by theJinas

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a ' ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable passa ...

". Similarly, the early Jain scholar Haribhadra, who likely lived between the 6th and 8th century, states that those who do not follow the teachings of Jainism cannot be "approved or accommodated".

John Koller states ''anekāntavāda'' to be "epistemological respect for view of others" about the nature of existence whether it is "inherently enduring or constantly changing", but "not relativism; it does not mean conceding that all arguments and all views are equal".

In contemporary times, according to Paul Dundas, the ''Anekantavada'' doctrine has been interpreted by some Jains as intending to "promote a universal religious tolerance", and a teaching of "plurality" and "benign attitude to other thical, religiouspositions". This is problematic and a misreading of Jain historical texts and Mahavira's teachings, states Dundas. The "many pointedness, multiple perspective" teachings of the Mahavira is a doctrine about the nature of Absolute Reality and human existence, and it is sometimes called "non-absolutism" doctrine. However, it is not a doctrine about tolerating or condoning activities such as sacrificing or killing animals for food, violence against disbelievers or any other living being as "perhaps right". The Five vows for Jain monks and nuns, for example, are strict requirements and there is no "perhaps, just one perspective". Similarly, since ancient times, Jainism co-existed with Buddhism and Hinduism, according to Dundas, but Jainism was highly critical of the knowledge systems and ideologies of its rivals, and vice versa.

History and development

The principle of ''anekāntavāda'' is one of the foundational Jain philosophical concept. The development of ''anekāntavāda'' also encouraged the development of the dialectics of ''syādvāda'' (conditioned viewpoints) and ''nayavāda'' (partial viewpoints). According to Karl Potter, the Jain ''anekāntavāda'' doctrine emerged in a milieu that included Buddhists and Hindus in ancient and medieval India. The diverse Hindu schools such as Nyaya-Vaisheshika, Samkhya-Yoga and Mimamsa-Vedanta, all accepted the premise ofAtman Atman or Ātman may refer to:

Film

* ''Ātman'' (1975 film), a Japanese experimental short film directed by Toshio Matsumoto

* ''Atman'' (1997 film), a documentary film directed by Pirjo Honkasalo

People

* Pavel Atman (born 1987), Russian hand ...

that "unchanging permanent soul, self exists and is self-evident", while various schools of early Buddhism denied it and substituted it with Anatta (no-self, no-soul). But the leading school of Buddhism named Shunyavada falls apart which says that there is no permanent soul or everything is Shunya (Empty) with argument that who is the witness of everything is Shunya (Emptiness). Further, for causation theories, Vedanta schools and Madhyamika Buddhists had similar ideas, while Nyaya-Vaisheshika and non-Madhyamika Buddhists generally agreed on the other side. Jainism, using its ''anekāntavāda'' doctrine occupied the center of this theological divide on soul-self (''jiva'') and causation theories, between the various schools of Buddhist and Hindu thought.

Origins

The origins of ''anekāntavāda'' are traceable in the teachings of Mahāvīra, who used it effectively to show the relativity of truth and reality. Taking a relativistic viewpoint, Mahāvīra is said to have explained the nature of the soul as both permanent, from the point of view of underlying substance, and temporary, from the point of view of its modes and modification.Early history

Early Jain texts were not composed in Vedic or classical Sanskrit, but in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit language. According to Matilal, the earliest Jain literature that present a developing form of a substantial ''anekantavada'' doctrine is found in Sanskrit texts, and after Jaina scholars had adopted Sanskrit to debate their ideas with Buddhists and Hindus of their era. These texts show a synthetic development, the existence and borrowing of terminology, ideas and concepts from rival schools of Indian thought but with innovation and original thought that disagreed with their peers. The early Svetambara canons and teachings do not use the terms ''anekāntavāda'' and ''syādvāda'', but contain teachings in rudimentary form without giving it proper structure or establishing it as a separate doctrine. ''Śvētāmbara'' text, '' Sutrakritanga'' contains references to ''Vibhagyavāda'', which, according to Hermann Jacobi, is the same as ''syādvāda'' and ''saptibhaṅgī''.Jacobi, Hermann (1895) 14:21–22 For example, Jacobi in his 1895 translation interpreted ''vibhagyavada'' as ''syadvada'', the former mentioned in the Svetambara Jain canonical text '' Sutrakritanga''. However, the Digambara Jains dispute this text is canonical or even authentic.Jaina canonEncyclopaedia Britannica According to Upadhyaye, the ''Bhagvatisūtra'' (also called Vyākhyāprajñapti) mentions three primary predications of the ''saptibhaṅgīnaya''.Upadhyaye, A. N. (2001) pp. 6136–37 This too is a Svetambara text, and considered by Digambara Jains as unauthentic. The earliest comprehensive teachings of anekāntavāda doctrine is found in the ''

Tattvarthasutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature '' ''artha">nowiki/>''artha''.html" ;"title="artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ...

'' of Umasvati, considered to be authoritative by all Jain sects including Svetambara and Digambara. The century in which Umaswati lived is unclear, but variously placed by contemporary scholars to sometime between 2nd and 5th century.

The Digambara scholar Kundakunda

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the 2nd CE century CE or later.

His date of birth is māgha māsa, śukla pakṣa, pañcamī tithi, on the day of Vasant Panchami.

He authored many Jain texts such ...

, in his mystical Jain texts, expounded on the doctrine of ''syādvāda'' and ''saptibhaṅgī'' in ''Pravacanasāra'' and '' Pancastikayasāra''. Kundakunda also used ''nayas'' to discuss the essence of the self

The self is an individual as the object of that individual’s own reflective consciousness. Since the ''self'' is a reference by a subject to the same subject, this reference is necessarily subjective. The sense of having a self—or ''selfhoo ...

in ''Samayasāra

''Samayasāra'' (''The Nature of the Self'') is a famous Jain text composed by '' Acharya Kundakunda'' in 439 verses. Its ten chapters discuss the nature of '' Jīva'' (pure self/soul), its attachment to Karma and Moksha (liberation). ''Samay ...

''. Kundakunda is believed in the Digambara tradition to have lived about the 1st-century CE, but has been placed by early modern era scholars to 2nd or 3rd century CE. In contrast, the earliest available secondary literature on Kundakunda appears in about the 10th century, which has led recent scholarship to suggest that he may have lived in or after 8th-century. This radical reassessment in Kundakunda chronology, if accurate, would place his comprehensive theories on ''anekantavada'' to the late 1st millennium CE.

Parable of the blind men and an elephant

The Jain texts explain the ''anekāntvāda'' concept using the parable of

The Jain texts explain the ''anekāntvāda'' concept using the parable of blind men and an elephant

The parable of the blind men and an elephant is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn and imagine what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elepha ...

, in a manner similar to those found in both Buddhist and Hindu texts about limits of perception and the importance of complete context. The parable has several Indian variations, but broadly goes as follows:

This parable is called ''Andha-gaja-nyaya'' maxim in Jain texts.

Two of the Jain references to this parable are found in ''Tattvarthaslokavatika'' of Vidyanandi (9th century) and it appears twice in the ''Syādvādamanjari'' of Ācārya Mallisena (13th century). According to Mallisena, whenever anyone takes a partial, unconditional view of the ultimate reality, and denies the possibility of another aspect of that reality, it is an instance of the above parable and a defective view. Mallisena goes further in his second reference to the above parable and states that all reality has infinite aspects and attributes, all assertions can only be relatively true. This does not mean scepticism or doubt is the right path to knowledge, according to Mallisena and other Jain scholars, but that any philosophical assertion is only conditionally, partially true. Any and all viewpoints, states Mallisena, that do not admit an exception are false views.

While the same parable is found in Buddhist and Hindu texts to emphasize the need to be watchful for partial viewpoints of a complex reality, the Jain text apply it to isolated topic and all subjects. For example, the ''syadvada'' principle states that all the following seven predicates must be accepted as true for a cooking pot, according to Matilal:

*from a certain point of view, or in a certain sense, the pot exists

*from a certain point of view, the pot does not exist

*from a certain point of view, the pot exists and does not exist

*from a certain point of view, the pot is inexpressible

*from a certain point of view, the pot both exists and is inexpressible

*from a certain point of view, the pot both does not exist and is inexpressible

*from a certain point of view, the pot exists, does not exist, and is also inexpressible

Medieval developments

Ācārya Haribhadra (8th century CE) was one of the leading proponents of ''anekāntavāda''. He wrote adoxography Doxography ( el, δόξα – "an opinion", "a point of view" + – "to write", "to describe") is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term w ...

, a compendium of a variety of intellectual views. This attempted to contextualise Jain thoughts within the broad framework, rather than espouse narrow partisan views. It interacted with the many possible intellectual orientations available to Indian thinkers around the 8th century.

Ācārya Amrtacandra starts his famous 10th century CE work ''Purusathasiddhiupaya'' with strong praise for ''anekāntavāda'': "I bow down to the principle of ''anekānta'', the source and foundation of the highest scriptures, the dispeller of wrong one-sided notions, that which takes into account all aspects of truth, reconciling diverse and even contradictory traits of all objects or entity."

Ācārya Vidyānandi (11th century CE) provides the analogy of the ocean to explain the nature of truth in ''Tattvarthaslokavārtikka'', 116:

, a 17th-century Jain monk, went beyond ''anekāntavāda'' by advocating ''madhāyastha'', meaning "standing in the middle" or "equidistance". This position allowed him to praise qualities in others even though the people were non-Jain and belonged to other faiths. There was a period of stagnation after Yasovijayaji, as there were no new contributions to the development of Jain philosophy.

Influence

The Jain philosophical concept of Anekantavada made important contributions to ancientIndian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Veda ...

, in the areas of skepticism and relativity.McEvilley, Thomas (2002) p. 335 The epistemology of ''anekāntavāda'' and ''syādvāda'' also had a profound impact on the development of ancient Indian logic and philosophy.

While employing ''anekāntavāda'', the 17th century Jain scholar Yasovijaya stated that it is not ''anābhigrahika'' (indiscriminate attachment to all views as being true), which is effectively a kind of misconceived relativism. In Jain belief, ''anekāntavāda'' transcends the various traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism.

Role in Jain history

''Anekāntavāda'' played a role in the history of Jainism in India, during intellectual debates fromŚaiva

Shaivism (; sa, शैवसम्प्रदायः, Śaivasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions rangi ...

s, Vaiṣṇavas, Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

s, Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s, and Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ� ...

at various times. According to John Koller, professor of Asian studies

Asian studies is the term used usually in North America and Australia for what in Europe is known as Oriental studies. The field is concerned with the Asian people, their cultures, languages, history and politics. Within the Asian sphere, Asia ...

, ''anekāntavāda'' allowed Jain thinkers to maintain the validity of their doctrine, while at the same time respectfully criticizing the views of their opponents. In other cases, it was a tool used by Jaina scholars to confront and dispute Buddhist scholars in ancient India, or in the case of Haribhadra justify the retaliation of the killing of his two nephews by Buddhist monks, with capital punishment for all Buddhist monks in the suspected monastery, according to the Buddhist version of Haribhadra's biography.

There is historical evidence that along with intolerance of non-Jains, Jains in their history have also been tolerant and generous just like Buddhists and Hindus. Their texts have never presented a theory for holy war. Jains and their temples have historically procured and preserved the classic manuscripts of Buddhism and Hinduism, a strong indicator of acceptance and plurality. The combination of historic facts, states Cort, suggest that Jain history is a combination or tolerance and intolerance of non-Jain views, and that it is inappropriate to rewrite the Jainism past as a history of "benevolence and tolerance" towards others.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi mentioned Anekantavada and Syadvada in the journal ''

Mahatma Gandhi mentioned Anekantavada and Syadvada in the journal ''Young India

''Young India'' was a weekly paper or journal in English founded by Lala Lajpat Rai in 1916 and later published by Mahatma Gandhi. Through this work, Mahatma Gandhi desired to popularise India's demand of self-government or Swaraj.

It was publ ...

– 21 Jan 1926''. According to Jeffery D. Long – a scholar of Hindu and Jain studies, the Jain Syadvada doctrine helped Gandhi explain how he reconciled his commitment to the "reality of both the personal and impersonal aspects of Brahman

In Hinduism, ''Brahman'' ( sa, ब्रह्मन्) connotes the highest universal principle, the ultimate reality in the universe.P. T. Raju (2006), ''Idealistic Thought of India'', Routledge, , page 426 and Conclusion chapter part X ...

", and his view of "Hindu religious pluralism":

Against religious intolerance and contemporary terrorism

Referring to theSeptember 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

, John Koller states that the threat to life from religious violence in modern society mainly exists due to faulty epistemology and metaphysics as well as faulty ethics. A failure to respect the life of other human beings and other life forms, states Koller, is "rooted in dogmatic but mistaken knowledge claims that fail to recognize other legitimate perspectives". Koller states that ''anekāntavāda'' is a Jain doctrine that each side commit to accepting truths of multiple perspectives, dialogue and negotiations.Koller, John (2004) pp. 85–98

According to Sabine Scholz, the application of the ''Anekantavada'' as a religious basis for "intellectual Ahimsa" is a modern era reinterpretation, one attributed to the writings of A.B. Dhruva in 1933. This view states that ''Anekantavada'' is an expression of "religious tolerance of other opinions and harmony". In the 21st century, some writers have presented it as an intellectual weapon against "intolerance, fundamentalism and terrorism". Other scholars such as John E. Cort

John E. Cort (born 1953) is an American indologist. He is a professor of Asian and Comparative Religions at Denison University, where he is also Chair of the Department of Religion. He has studied Jainism and the history of Jain society over fo ...

and Paul Dundas state that, while Jainism indeed teaches non-violence as the highest ethical value, the reinterpretation of ''Anekantavada'' as "religious tolerance of other opinions" is a "misreading of the original doctrine". In Jain history, it was a metaphysical doctrine and a philosophical method to formulate its distinct ascetic practice of liberation. Jain history shows, to the contrary, that it persistently was harshly critical and intolerant of Buddhist and Hindu spiritual theories, beliefs and ideologies. John Cort states that the ''Anekantavada'' doctrine in pre-20th century Jain literature had no relation to religious tolerance or "intellectual Ahimsa". Jain intellectual and social history toward non-Jains, according to Cort, has been contrary to the modern revisionist attempts, particularly by diaspora Jains, to present "Jains having exhibited a spirit of understanding and tolerance toward non-Jains", or that Jains were rare or unique in practicing religious tolerance in Indian intellectual history. According to Padmanabha Jaini, states Cort, indiscriminate open mindedness and the approach of "accepting all religious paths as equally correct when in fact they are not" is an erroneous view in Jainism and not supported by the ''Anekantavada'' doctrine.

According to Paul Dundas, in and after the 12th century, the persecution and violence against Jains by Muslim state caused Jain scholars to revisit their theory of Ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

(non-violence). For example, Jinadatta Suri in 12th century, wrote during a time of widespread destruction of Jain temples and blocking of Jaina pilgrimage by Muslim armies, that "anybody engaged in a religious activity who was forced to fight and kill somebody" in self-defense would not lose any merit. N.L. Jain, quoting Acarya Mahaprajna, states ''Anekantavada'' doctrine is not a principle that can be applied to all situations or fields. In his view, the doctrine has its limits and ''Anekantavada'' doctrine does not mean intellectual tolerance or acceptance of religious violence, terrorism, taking of hostages, proxy wars such as in Kashmir, and that "to initiate a conflict is as sinful as to tolerate or not oppose it".

The reinterpretation of ''Anekantavada'' as a doctrine of religious tolerance is novel, popular but not unusual for contemporary Jains. It is a pattern of reinterpretation and reinvention to rebrand and reposition that is found in many religions, states Scholz.

Comparison with non-Jain doctrines

According to Bhagchandra Jain, one of the difference between the Buddhist and Jain views is that "Jainism accepts all statements to possess some relative (''anekāntika'') truth" while for Buddhism this is not the case. In Jainism, states Jayatilleke, "no proposition could in theory be asserted to be categorically true or false, irrespective of the standpoint from which it was made, in Buddhism such categorical assertions were considered possible in the case of some propositions."Jayatilleke; Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. Publisher: George Allen and Unwin, 1963, pp. 279-280. Unlike Jainism, there are propositions that are categorically true in Buddhism, and there are others that are ''anekamsika'' (uncertain, indefinite). Examples of categorically true and certain doctrines are theFour Noble Truths

In Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths (Sanskrit: ; pi, cattāri ariyasaccāni; "The four Arya satyas") are "the truths of the Noble Ones", the truths or realities for the "spiritually worthy ones". avyakata-theses. Further, unlike Jainism, Buddhism does not have a Nayavāda doctrine.

According to Karl Potter and other scholars, Hinduism developed various theory of relations such as ''satkaryavada'', ''asatkaryavada'', ''avirodhavada'' and others. The ''anekantavada'' overlaps with two major theories found in Hindu and Buddhist thought, according to James Lochtefeld. The ''Anekantavada'' doctrine is ''satkaryavada'' in explaining causes, and the ''asatkaryavada'' in explaining qualities or attributes in the effects. The different schools of Hindu philosophy further elaborated and refined the theory of ''pramanas'' and the theory of relations to establish correct means to structure propositions in their view.

Criticism

Indologists such as professorJohn E. Cort

John E. Cort (born 1953) is an American indologist. He is a professor of Asian and Comparative Religions at Denison University, where he is also Chair of the Department of Religion. He has studied Jainism and the history of Jain society over fo ...

state that ''anekāntavāda'' is a doctrine that was historically used by Jain scholars not to accept other viewpoints, but to insist on the Jain viewpoint. Jain monks used ''anekāntavāda'' and ''syādvāda'' as debating weapons to silence their critics and defend the Jain doctrine. According to Paul Dundas, in Jain hands, this method of analysis became "a fearsome weapon of philosophical polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

with which the doctrines of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

and Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

could be pared down to their ideological bases of simple permanence and impermanence, respectively, and thus could be shown to be one-pointed and inadequate as the overall interpretations of reality they purported to be".Dundas, Paul (2002) p. 231 The Jain scholars, however, considered their own theory of ''Anekantavada'' self-evident, immune from criticism, needing neither limitations nor conditions.

The doctrines of ''anekāntavāda'' and ''syādavāda'' are often criticised to denying any certainty, or accepting incoherent contradictory doctrines. Another argument against it, posited by medieval era Buddhists and Hindus applied the principle on itself, that is if nothing is definitely true or false, is ''anekāntavāda'' true or false?

According to Karl Potter, the ''Anekantavada'' doctrine accepts the norm in Indian philosophies that all knowledge is contextual, that object and subject are interdependent. However, as a theory of relations, it does not solve the deficiencies in other progress philosophies, just "compounds the felony by merely duplicating the already troublesome notion of a dependence relation".

Hindu philosophies

Nyaya

TheNyaya

(Sanskrit: न्याय, ''nyā-yá''), literally meaning "justice", "rules", "method" or "judgment", The Naiyayikas states that it makes no sense to simultaneously say, "jiva and ajiva are not related" and "jiva and ajiva are related". Jains state that ''jiva'' attaches itself to karmic particles (ajiva) which means there is a relation between ajiva and jiva. The Jain theory of ascetic salvation teaches cleansing of karmic particles and destroying the bound ajiva to the jiva, yet, Jain scholars also deny that ajiva and jiva are related or at least interdependent, according to the Nyaya scholars. The Jain theory of ''anekantavada'' makes its theory of karma, asceticism and salvation incoherent, according to Nyaya texts.

The Doctrine of Relative Pluralism (anekāntavāda)

Surendranath Dasgupta, 1940

Pravin K. Shah on Anekantvada

by

The Syadvada System of Predication

by

Anekantvada

.

The Pluralism Project

at

Vaisheshika

The Vaisheshika andShaivism

Shaivism (; sa, शैवसम्प्रदायः, Śaivasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions rangi ...

school scholar Vyomashiva criticized the ''Anekantavada'' doctrine because, according to him, it makes all moral life and spiritual pursuits for moksha

''Moksha'' (; sa, मोक्ष, '), also called ''vimoksha'', ''vimukti'' and ''mukti'', is a term in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism for various forms of emancipation, enlightenment, liberation, and release. In its soteriologic ...

meaningless. Any spiritually liberated person must be considered under ''Anekantavada'' doctrine to be both liberated and not liberated from one point of view, and simply not liberated from another point of view, since all assertions are to be qualified and conditional under it. In other words, states Vyomashiva, this doctrine leads to a paradox and circularity.

Vedanta

''Anekāntavāda'' was analyzed and critiqued by Adi Śankarācārya (~800 CE) in his ''bhasya'' on '' Brahmasutra'' (2:2:33–36): He stated that ''anekantavada'' doctrine when applied to philosophy suffers from two problems: ''virodha'' (contradictions) and ''samsaya'' (dubiety), neither of which it is able to reconcile with objectivity. Shankara's criticism of ''anekantavada'' extended beyond the arguments of it being incoherent epistemology in ontological matters. According to Shankara, the goal of philosophy is to identify one's doubts and remove them through reason and understanding, not get more confused. The problem with ''anekantavada'' doctrine is that it compounds and glorifies confusion. Further, states Shankara, Jains use this doctrine to be "certain that everything is uncertain". Contemporary scholars, states Piotr Balcerowicz, concur that the Jain doctrine of ''Anekantavada'' does reject some versions of the "law of non-contradiction", but it is incorrect to state that it rejects this law in all instances., Quote: "This is the sense in which it is correct to say that the Jainas reject the "law of non-contradiction".Buddhist philosophy

The Buddhist scholarŚāntarakṣita

(Sanskrit; , 725–788),stanford.eduŚāntarakṣita (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)/ref> whose name translates into English as "protected by the One who is at peace" was an important and influential Indian Buddhist philosopher, particul ...

, and his student Kamalasila, criticized ''anekantavada'' by presenting his arguments that it leads to the Buddhist premise "jivas (souls) do not exist". That is, the two of the most important doctrines of Jainism are mutually contradictory premises. According to Santaraksita, Jains state that "jiva is one considered collectively, and many considered distributively", but if so debates Santaraksita, "jiva cannot change". He then proceeds to show that changing jiva necessarily means jiva appear and disappear every moment, which is equivalent to "jiva don't exist". According to Karl Potter, the argument posited by Śāntarakṣita is flawed, because it commits what is called in the Western logic as the "fallacy of division".

The Buddhist logician Dharmakirti critiqued ''anekāntavāda'' as follows:

Self-criticism in Jain scholarship

The medieval era Jain logiciansAkalanka

Akalanka (also known as ''Akalank Deva'' and ''Bhatta Akalanka'') was a Jain logician whose Sanskrit-language works are seen as landmarks in Indian logic. He lived from 720 to 780 A.D. and belonged to the Digambara sect of Jainism. His work ''As ...

and Vidyananda, who were likely contemporaries of Adi Shankara, acknowledged many issues with anekantavada in their texts. For example, Akalanka in his ''Pramanasamgraha'' acknowledges seven problems when ''anekantavada'' is applied to develop a comprehensive and consistent philosophy: dubiety, contradiction, lack of conformity of bases (), joint fault, infinite regress, intermixture and absence. Vidyananda acknowledged six of those in the Akalanka list, adding the problem of ''vyatikara'' (cross breeding in ideas) and ''apratipatti'' (incomprehensibility). Prabhācandra

Prabhācandra (c. 11th century CE) was a Digambara monk,grammarian,biographer, philosopher and author of several philosophical books on Jainism.

Life

Prabhachandra was a ''Digambara monk'' who flourished in 11th century CE. He denied the possib ...

, who probably lived in the 11th century, and several other later Jain scholars accepted many of these identified issues in ''anekantavada'' application.

See also

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * ** ** ** * * * * * * * ''Note: ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1884 reprint.'' * ''Note:ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1895 reprint.'' * * * * * * * * * * * * ** ** ** * * * * * * * * *External links

The Doctrine of Relative Pluralism (anekāntavāda)

Surendranath Dasgupta, 1940

Pravin K. Shah on Anekantvada

by

P. C. Mahalanobis

Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis OBE, FNA, FASc, FRS (29 June 1893– 28 June 1972) was an Indian scientist and statistician. He is best remembered for the Mahalanobis distance, a statistical measure, and for being one of the members of the first ...

, Dialectica 8, 1954, 95–111.

The Syadvada System of Predication

by

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolo ...

, Sankhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, '' puruṣa'' ('consciousness' or spirit); and ''prakṛti'', (nature ...

18, 195–200, 1957.Anekantvada

.

The Pluralism Project

at

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

.

{{featured article

Jain philosophical concepts

Religious pluralism

Relativism