Sumerian civilization on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sumer () is the earliest known

Others have suggested that the Sumerians were a

Others have suggested that the Sumerians were a  Some scholars contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language; they think the Sumerian language may originally have been that of the

Some scholars contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language; they think the Sumerian language may originally have been that of the

The Sumerian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic III period, c. 23rd century BC, when a now deciphered syllabary writing system was developed, which has allowed archaeologists to read contemporary records and inscriptions. The

The Sumerian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic III period, c. 23rd century BC, when a now deciphered syllabary writing system was developed, which has allowed archaeologists to read contemporary records and inscriptions. The

The dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2270 BC), though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of

The dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2270 BC), though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC ( middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC ( middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic

c. 2200–2110 BC (middle chronology)

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of

c. 2200–2110 BC (middle chronology)

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of

Later, the Third Dynasty of Ur under

Later, the Third Dynasty of Ur under

In the early Sumerian period, the primitive pictograms suggest that

* "Pottery was very plentiful, and the forms of the vases, bowls and dishes were manifold; there were special jars for honey, butter, oil and wine, which was probably made from dates. Some of the vases had pointed feet, and stood on stands with crossed legs; others were flat-bottomed, and were set on square or rectangular frames of wood. The oil-jars, and probably others also, were sealed with clay, precisely as in early

In the early Sumerian period, the primitive pictograms suggest that

* "Pottery was very plentiful, and the forms of the vases, bowls and dishes were manifold; there were special jars for honey, butter, oil and wine, which was probably made from dates. Some of the vases had pointed feet, and stood on stands with crossed legs; others were flat-bottomed, and were set on square or rectangular frames of wood. The oil-jars, and probably others also, were sealed with clay, precisely as in early

“Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian”

. In S.L. Sanders (ed) ''Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture'': 91–120 Chicago but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Babylonia and Assyria until the 1st century AD.

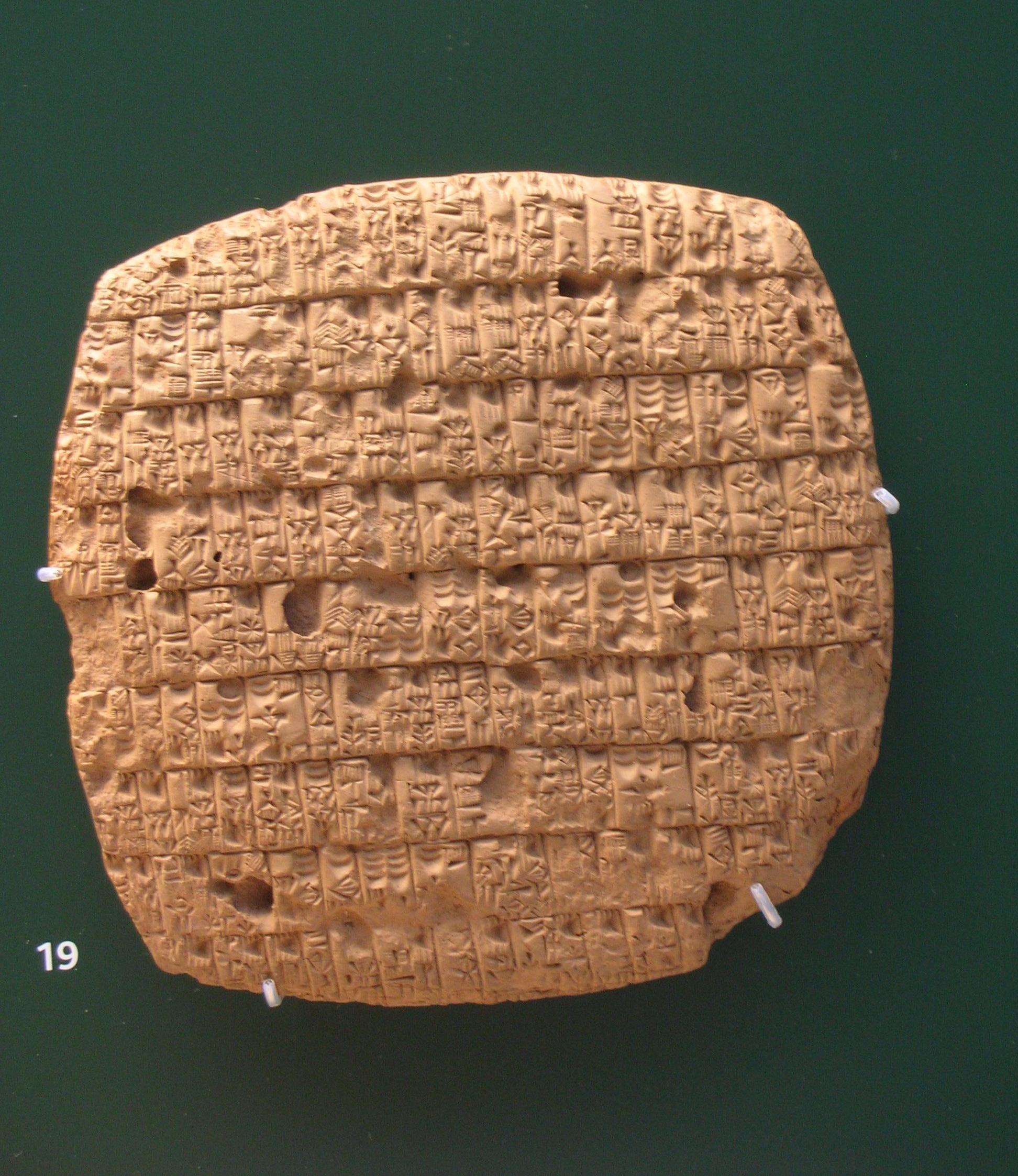

File:Early writing tablet recording the allocation of beer.jpg, Early writing tablet for recording the allocation of beer; 3100–3000 BC; height: 9.4 cm; width: 6.87 cm; from Iraq;

Sumerians believed in an anthropomorphic polytheism, or the belief in many gods in human form. There was no common set of gods; each city-state had its own patrons, temples, and priest-kings. Nonetheless, these were not exclusive; the gods of one city were often acknowledged elsewhere. Sumerian speakers were among the earliest people to record their beliefs in writing, and were a major inspiration in later Mesopotamian mythology,

Sumerians believed in an anthropomorphic polytheism, or the belief in many gods in human form. There was no common set of gods; each city-state had its own patrons, temples, and priest-kings. Nonetheless, these were not exclusive; the gods of one city were often acknowledged elsewhere. Sumerian speakers were among the earliest people to record their beliefs in writing, and were a major inspiration in later Mesopotamian mythology,  These

These

In the early Sumerian Uruk period, the primitive pictograms suggest that

In the early Sumerian Uruk period, the primitive pictograms suggest that  The Sumerians were one of the first known

The Sumerians were one of the first known

The Sumerians were great creators, nothing proving this more than their art. Sumerian artifacts show great detail and ornamentation, with fine semi-precious stones imported from other lands, such as

The Sumerians were great creators, nothing proving this more than their art. Sumerian artifacts show great detail and ornamentation, with fine semi-precious stones imported from other lands, such as

Cylinder seal and modern impression- ritual scene before a temple facade MET DP270679.jpg, Cylinder seal and impression in which appears a ritual scene before a temple façade; 3500–3100 BC; bituminous limestone; height: 4.5 cm;

The Tigris-Euphrates plain lacked minerals and trees. Sumerian structures were made of plano-convex mudbrick, not fixed with mortar or

The Tigris-Euphrates plain lacked minerals and trees. Sumerian structures were made of plano-convex mudbrick, not fixed with mortar or

Discoveries of

Discoveries of

The almost constant wars among the Sumerian city-states for 2000 years helped to develop the military technology and techniques of Sumer to a high level. The first war recorded in any detail was between Lagash and Umma in c. 2450 BC on a stele called the

The almost constant wars among the Sumerian city-states for 2000 years helped to develop the military technology and techniques of Sumer to a high level. The first war recorded in any detail was between Lagash and Umma in c. 2450 BC on a stele called the

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appeared in the mid-4th millennium BC, near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus (

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appeared in the mid-4th millennium BC, near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus (

The Sumerians

''. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

* ttp://www.penn.museum/sites/iraq/ Iraq’s Ancient Past–

A brief introduction to Sumerian history

;Geography * The History Files

;Language

Sumerian Language Page

perhaps the oldest Sumerian website on the web (it dates back to 1996), features compiled lexicon, detailed FAQ, extensive links, and so on.

ETCSL: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

has complete translations of more than 400 Sumerian literary texts.

PSD: ''The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary''

while still in its initial stages, can be searched on-line, from August 2004.

CDLI: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

a large corpus of Sumerian texts in transliteration, largely from the Early Dynastic and Ur III periods, accessible with images. {{Authority control States and territories established in the 4th millennium BC States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC States and territories disestablished in the 20th century BC Bronze Age civilizations Lists of coordinates Archaeology of Iraq Levant Populated places established in the 6th millennium BC 6th-millennium BC establishments

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

(south-central Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

), emerging during the Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of civilization

A cradle of civilization is a location and a culture where civilization was created by mankind independent of other civilizations in other locations. The formation of urban settlements (cities) is the primary characteristic of a society that c ...

in the world, along with ancient Egypt, Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

, the Caral-Supe civilization

Caral-Supe (also known as Caral and Norte Chico) was a complex pre-Columbian-era society that included as many as thirty major population centers in what is now the Caral region of north-central coastal Peru. The civilization flourished betwee ...

, Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

, the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900& ...

, and ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

. Living along the valleys of the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, the surplus from which enabled them to form urban settlements. Proto-writing

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information. Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in Eastern Europe and China. They used ideogra ...

dates back before 3000 BC. The earliest texts come from the cities of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Muthanna Governorate, Al ...

and Jemdet Nasr

Jemdet Nasr ( ar, جمدة نصر) is a tell or settlement mound in Babil Governorate (Iraq) that is best known as the eponymous type site for the Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC), and was one of the oldest Sumerian cities. The site was fir ...

, and date to between c. 3500 and c. 3000 BC.

Name

The term "Sumer" ( Sumerian: or ,Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

: ) is the name given to the language spoken by the "Sumerians", the ancient non- Semitic-speaking inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, by their successors the East Semitic-speaking Akkadians

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rul ...

. The Sumerians referred to their land as , the 'Country of the noble lords' (, , lit. 'country' + 'lords' + 'noble') as seen in their inscriptions."The area in question (the extreme south of Mesopotamia) may now be called Sumer, and its inhabitants Sumerians, although these names are only English approximations of the Akkadian designations; the Sumerians themselves called their land Kengir, their language Emegir, and themselves Sag-giga, "black-headed ones." in

The origin of the Sumerians is not known, but the people of Sumer referred to themselves as "Black Headed Ones" or "Black-Headed People" ( , , lit. 'head' + 'black', or , phonetically , lit. 'head' + 'black' + 'carry'). For example, the Sumerian king Shulgi

Shulgi ( dŠulgi, formerly read as Dungi) of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC (Middle Chronology) or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC (Short Chronology). His accomplishme ...

described himself as "the king of the four quarters, the pastor of the black-headed people". The Akkadians also called the Sumerians 'black-headed people', or , in the Semitic Akkadian language.

The Akkadian word may represent the geographical name in dialect, but the phonological

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

development leading to the Akkadian term is uncertain. Hebrew , Egyptian , and Hittite , all referring to southern Mesopotamia, could be western variants of ''Sumer''.

Origins

Most historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled between c. 5500 and 4000 BC by aWest Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes ...

n people who spoke the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc., as evidence), a non-Semitic and non-Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

agglutinative

In linguistics, agglutination is a morphological process in which words are formed by stringing together morphemes, each of which corresponds to a single syntactic feature. Languages that use agglutination widely are called agglutinative l ...

language isolate

Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families. Korean and Basque are two of the most common examples. Other language isolates include Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, and Haida in North America. The nu ...

. In contrast to its Semitic neighbours, it was not an inflected

In linguistic morphology, inflection (or inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and de ...

language.

Others have suggested that the Sumerians were a

Others have suggested that the Sumerians were a North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

n people who migrated from the Green Sahara

The African humid period (AHP) (also known by other names) is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, ...

into the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and were responsible for the spread of farming in the Middle East. However, with evidence strongly suggesting the first farmers originated from the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

, this suggestion is often discarded. Although not specifically discussing Sumerians, Lazaridis et al. 2016 have suggested a partial North African origin for some pre-Semitic cultures of the Middle East, particularly Natufians, after testing the genomes of Natufian and Pre-Pottery Neolithic

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent, dating to years ago, (10000 – 6500 BCE).Richard, Suzanne ''Near Eastern archaeology'' Eisenbrauns; il ...

culture-bearers. Alternatively, a recent (2013) genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with Indus Valley Civilization, possibly as a result of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations. According to some data, the Sumerians are associated with the Hurrians

The Hurrians (; cuneiform: ; transliteration: ''Ḫu-ur-ri''; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri or Hurriter) were a people of the Bronze Age Near East. They spoke a Hurrian language and lived in Anatolia, Syria and Northern Me ...

and Urartians, and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

is considered their homeland.

A prehistoric people who lived in the region before the Sumerians have been termed the " Proto-Euphrateans" or " Ubaidians", and are theorized to have evolved from the Samarra culture of northern Mesopotamia. The Ubaidians, though never mentioned by the Sumerians themselves, are assumed by modern-day scholars to have been the first civilizing force in Sumer. They drained the marshes for agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, developed trade, and established industries, including weaving

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal ...

, leatherwork, metalwork

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on every scale ...

, masonry

Masonry is the building of structures from individual units, which are often laid in and bound together by mortar; the term ''masonry'' can also refer to the units themselves. The common materials of masonry construction are bricks, building ...

, and pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

.

Some scholars contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language; they think the Sumerian language may originally have been that of the

Some scholars contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language; they think the Sumerian language may originally have been that of the hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

and fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from fish stocking, stocked bodies of water such as fish pond, ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. ...

peoples who lived in the marshland and the Eastern Arabia littoral region and were part of the Arabian bifacial culture. Reliable historical records begin much later; there are none in Sumer of any kind that have been dated before Enmebaragesi ( Early Dynastic I). Juris Zarins

Juris Zarins (Zariņš) (born 1945, in Germany) is an American-Latvian archaeologist and professor at Missouri State University, who specializes in the Middle East.

Biography

Zarins is ethnically Latvian, but was born in Germany at the end of ...

believes the Sumerians lived along the coast of Eastern Arabia, today's Persian Gulf region, before it was flooded at the end of the Ice Age.

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period

The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named af ...

(4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdet Nasr

Jemdet Nasr ( ar, جمدة نصر) is a tell or settlement mound in Babil Governorate (Iraq) that is best known as the eponymous type site for the Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC), and was one of the oldest Sumerian cities. The site was fir ...

and Early Dynastic periods.

The Sumerians progressively lost control to Semitic states from the northwest. Sumer was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BC (short chronology

The chronology of the ancient Near East is a framework of dates for various events, rulers and dynasties. Historical inscriptions and texts customarily record events in terms of a succession of officials or rulers: "in the year X of king Y". Com ...

), but Sumerian continued as a sacred language

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily in church service or for other religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Concept

A sac ...

. Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

at approximately 2100–2000 BC, but the Akkadian language also remained in use for some time.Leick, Gwendolyn (2003), "Mesopotamia, the Invention of the City" (Penguin)

The Sumerian city of Eridu

Eridu (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , NUN.KI/eridugki; Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''irîtu''; modern Arabic language, Arabic: Tell Abu Shahrain) is an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia (modern Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq). Eridu was l ...

, on the coast of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, is considered to have been one of the oldest cities, where three separate cultures may have fused: that of peasant Ubaidian farmers, living in mud-brick huts and practicing irrigation; that of mobile nomadic Semitic pastoralists living in black tents and following herds of sheep and goats; and that of fisher folk, living in reed huts in the marshlands, who may have been the ancestors of the Sumerians.

City-states in Mesopotamia

In the late 4th millennium BC, Sumer was divided into many independentcity-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s, which were divided by canals and boundary stones. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a priestly governor ( ensi) or by a king (lugal

Lugal ( Sumerian: ) is the Sumerian term for "king, ruler". Literally, the term means "big man." In Sumerian, ''lu'' "𒇽" is "man" and ''gal'' " 𒃲" is "great," or "big."

It was one of several Sumerian titles that a ruler of a city-state coul ...

) who was intimately tied to the city's religious rites.

The five "first" cities, said to have exercised pre-dynastic kingship "before the flood":

# Eridu

Eridu (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , NUN.KI/eridugki; Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''irîtu''; modern Arabic language, Arabic: Tell Abu Shahrain) is an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia (modern Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq). Eridu was l ...

(''Tell Abu Shahrain'')

# Bad-tibira (probably ''Tell al-Madain)''

# Larak

# Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

(''Tell Abu Habbah'')

# Shuruppak

Shuruppak ( sux, , "the healing place"), modern Tell Fara, was an ancient Sumerian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. Shuruppak was dedicated to ...

(''Tell Fara'')

Other principal cities:

Minor cities (from south to north):

# Kuara (''Tell al-Lahm'')

# Zabala (''Tell Ibzeikh'')

# Kisurra

Kisurra (modern Tell Abu Hatab, Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian '' tell'' (hill city) situated on the west bank of the Euphrates, north of Shuruppak and due east of Kish.

History

Kisurra was established ca. 2700 BC ...

(''Tell Abu Hatab'')

# Marad

Marad (Sumerian: Marda, modern Tell Wannat es-Sadum or Tell as-Sadoum, Iraq) was an ancient Near Eastern city. Marad was situated on the west bank of the then western branch of the Upper Euphrates River west of Nippur in modern-day Iraq and ro ...

(''Tell Wannat es-Sadum'')

# Dilbat (''Tell ed-Duleim'')

# Borsippa

Borsippa ( Sumerian: BAD.SI.(A).AB.BAKI; Akkadian: ''Barsip'' and ''Til-Barsip'')The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. or Birs Nimrud (having been identified with Nimrod) is an archeologi ...

(''Birs Nimrud'')

# Kutha

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha ( ar, كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gudua), modern Tell Ibrahim ( ar, تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), formerly known as Kutha Rabba ( ar, كُوثَىٰ رَبَّا), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. ...

(''Tell Ibrahim'')

# Der (''al-Badra'')

# Eshnunna

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia 12.6 miles northwest of Tell Agrab and 15 miles northwest of Tell Ishchali. Although situated in the ...

(''Tell Asmar'')

# Nagar

Nagar ( -nagar) can refer to:

Places Bangladesh

* Nagar, Rajshahi Division, a village

* Nagar, Barisal Division, a settlement

India

* Nagar taluka, Ahmednagar, Maharashtra State

* Nagar, Murshidabad, a village in West Bengal

* Nagar, Rajasthan ...

(''Tell Brak'')

(an outlying city in northern Mesopotamia)

Apart from Mari, which lies full 330 kilometres (205 miles) north-west of Agade, but which is credited in the king list as having "exercised kingship" in the Early Dynastic II period, and Nagar, an outpost, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

in what are now the Bābil, Diyala, Wāsit, Dhi Qar, Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

, Al-Muthannā and Al-Qādisiyyah governorates of Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

History

The Sumerian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic III period, c. 23rd century BC, when a now deciphered syllabary writing system was developed, which has allowed archaeologists to read contemporary records and inscriptions. The

The Sumerian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic III period, c. 23rd century BC, when a now deciphered syllabary writing system was developed, which has allowed archaeologists to read contemporary records and inscriptions. The Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one r ...

was the first state that successfully united larger parts of Mesopotamia in the 23rd century BC. After the Gutian period

The Gutian dynasty, also Kuti or Kutians ( Sumerian: , gu-ti-umKI) was a dynasty, originating among the Gutian people, that came to power in Mesopotamia ''c.'' 2199—2119 BC ( middle), or possibly ''c.'' 2135—2055 BC ( short), after displacin ...

, the Ur III kingdom similarly united parts of northern and southern Mesopotamia. It ended in the face of Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied lar ...

incursions at the beginning of the second millennium BC. The Amorite "dynasty of Isin

Isin (, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. Excavations have shown that it was an important city-state in the past.

History of archaeological research

Ishan al-Bahriyat was visited ...

" persisted until c. 1700 BC, when Mesopotamia was united under Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

n rule.

* Ubaid period

The Ubaid period (c. 6500–3700 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Wo ...

: 6500–4100 BC (Pottery Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

to Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

)

* Uruk period

The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named af ...

: 4100–2900 BC (Late Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

to Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

I)

** Uruk XIV–V: 4100–3300 BC

** Uruk IV period: 3300–3100 BC

** Jemdet Nasr period

The Jemdet Nasr Period is an archaeological culture in southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). It is generally dated from 3100 to 2900 BC. It is named after the type site Tell Jemdet Nasr, where the assemblage typical for this period was first r ...

(Uruk III): 3100–2900 BC

* Early Dynastic period (Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

II–IV)

** Early Dynastic I period: 2900–2800 BC

** Early Dynastic II period: 2800–2600 BC (Gilgamesh

sux, , label=none

, image = Hero lion Dur-Sharrukin Louvre AO19862.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assy ...

)

** Early Dynastic IIIa period: 2600–2500 BC

** Early Dynastic IIIb period: c. 2500–2334 BC

* Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one r ...

period: c. 2334–2218 BC ( Sargon)

* Gutian period

The Gutian dynasty, also Kuti or Kutians ( Sumerian: , gu-ti-umKI) was a dynasty, originating among the Gutian people, that came to power in Mesopotamia ''c.'' 2199—2119 BC ( middle), or possibly ''c.'' 2135—2055 BC ( short), after displacin ...

: c. 2218–2047 BC (Early Bronze Age IV)

* Ur III period

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC (middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

: c. 2047–1940 BC

Ubaid period

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Mesopotamia and thePersian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

. The oldest evidence for occupation comes from Tell el-'Oueili

Tell el-'Oueili (also Awayli) is a tell, or ancient settlement mound, located in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. The site was excavated between 1976 and 1989 by French archaeologists under the direction of Jean-Louis Huot. The excavations hav ...

, but, given that environmental conditions in southern Mesopotamia were favourable to human occupation well before the Ubaid period, it is likely that older sites exist but have not yet been found. It appears that this culture was derived from the Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional ar ...

n culture from northern Mesopotamia. It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. The story of the passing of the gifts of civilization ( ''me'') to Inanna

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki

, image = Enki(Ea).jpg

, caption = Detail of Enki from the Adda Seal, an ancient Akkadian cylinder seal dating to circa 2300 BC

, deity_of = God of creation, intelligence, crafts, water, seawater, lakewater, fertility, semen, magic, mischief

...

, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect the transition from Eridu to Uruk.

Uruk period

The archaeological transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift from painted pottery domestically produced on a slowwheel

A wheel is a circular component that is intended to rotate on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be ...

to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on fast wheels. The Uruk period is a continuation and an outgrowth of Ubaid with pottery being the main visible change.

By the time of the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC calibrated), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified

Stratification may refer to:

Mathematics

* Stratification (mathematics), any consistent assignment of numbers to predicate symbols

* Data stratification in statistics

Earth sciences

* Stable and unstable stratification

* Stratification, or st ...

, temple-centered cities (with populations of over 10,000 people) where centralized administrations employed specialized workers. It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labour

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

captured from the hill country, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts. Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area—from the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

in the west, and as far east as western Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Algaze, Guillermo (2005). '' The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization'', Second Edition, University of Chicago Press.

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists (like that found at Tell Brak

Tell Brak (Nagar, Nawar) was an ancient city in Syria; its remains constitute a tell located in the Upper Khabur region, near the modern village of Tell Brak, 50 kilometers north-east of Al-Hasaka city, Al-Hasakah Governorate. The city' ...

), had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.

Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

and were most likely headed by a priest-king (''ensi''), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women.Jacobsen, Thorkild (Ed) (1939),"The Sumerian King List" (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; Assyriological Studies, No. 11., 1939) It is quite possible that the later Sumerian pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone St ...

was modeled upon this political structure. There was little evidence of organized warfare or professional soldiers during the Uruk period, and towns were generally unwalled. During this period Uruk became the most urbanized city in the world, surpassing for the first time 50,000 inhabitants.

The ancient Sumerian king list includes the early dynasties of several prominent cities from this period. The first set of names on the list is of kings said to have reigned before a major flood occurred. These early names may be fictional, and include some legendary and mythological figures, such as Alulim

, successor =Alalngar

, native_lang1 = Sumerian

, native_lang1_name1=

}

Alulim; transliterated: ; ; grc-gre, Ἄλωρος, ''Alōros''; ar, الوروس, (; ; ; ) is the first king whose name appears on numerous versions of the Sumeria ...

and Dumizid.

The end of the Uruk period coincided with the Piora oscillation, a dry period from c. 3200–2900 BC that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, called the Holocene climatic optimum

The Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO) was a warm period that occurred in the interval roughly 9,000 to 5,000 years ago BP, with a thermal maximum around 8000 years BP. It has also been known by many other names, such as Altithermal, Climatic Optimu ...

.

Early Dynastic Period

The dynastic period begins c. 2900 BC and was associated with a shift from the temple establishment headed by council of elders led by a priestly "En" (a male figure when it was a temple for a goddess, or a female figure when headed by a male god) towards a more secular Lugal (Lu = man, Gal = great) and includes such legendary patriarchal figures asDumuzid

Dumuzid or Tammuz ( sux, , ''Dumuzid''; akk, Duʾūzu, Dûzu; he, תַּמּוּז, Tammûz),; ar, تمّوز ' known to the Sumerians as Dumuzid the Shepherd ( sux, , ''Dumuzid sipad''), is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with shep ...

, Lugalbanda

Lugalbanda was a deified Sumerian king of Uruk who, according to various sources of Mesopotamian literature, was the father of Gilgamesh. Early sources mention his consort Ninsun and his heroic deeds in an expedition to Aratta by King Enmerka ...

and Gilgamesh

sux, , label=none

, image = Hero lion Dur-Sharrukin Louvre AO19862.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assy ...

—who reigned shortly before the historic record opens c. 2900 BC, when the now deciphered syllabic writing started to develop from the early pictograms. The center of Sumerian culture remained in southern Mesopotamia, even though rulers soon began expanding into neighboring areas, and neighboring Semitic groups adopted much of Sumerian culture for their own.

The earliest dynastic king on the Sumerian king list whose name is known from any other legendary source is Etana, 13th king of the first dynasty of Kish. The earliest king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Enmebaragesi of Kish (Early Dynastic I), whose name is also mentioned in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with ...

''—leading to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself might have been a historical king of Uruk. As the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' shows, this period was associated with increased war. Cities became walled, and increased in size as undefended villages in southern Mesopotamia disappeared. (Both Enmerkar and Gilgamesh are credited with having built the walls of Uruk.)

1st Dynasty of Lagash

The dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2270 BC), though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of

The dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2270 BC), though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of Eannatum

Eannatum ( sux, ) was a Sumerian '' Ensi'' (ruler or king) of Lagash circa 2500–2400 BCE. He established one of the first verifiable empires in history: he subdued Elam and destroyed the city of Susa as well as several other Iranian cities, ...

of Lagash, who annexed practically all of Sumer, including Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

, and reduced to tribute the city-state of Umma

Umma ( sux, ; in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, formerly also called Gishban) was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell J ...

, arch-rival of Lagash. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

and along the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

. He seems to have used terror as a matter of policy. Eannatum's Stele of the Vultures

The Stele of the Vultures is a monument from the Early Dynastic IIIb period (2600–2350 BC) in Mesopotamia celebrating a victory of the city-state of Lagash over its neighbour Umma. It shows various battle and religious scenes and is named aft ...

depicts vultures pecking at the severed heads and other body parts of his enemies. His empire collapsed shortly after his death.

Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He was the last ethnically Sumerian king before Sargon of Akkad

Sargon of Akkad (; akk, ''Šarrugi''), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.The date of the reign of Sargon is highl ...

.

Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC ( middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC ( middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic Akkadian language

Akkadian (, Akkadian: )John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, "Akkadian and Eblaite", ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages''. Ed. Roger D. Woodard (2004, Cambridge) Pages 218-280 is an extinct East Semitic language t ...

is first attested in proper names of the kings of Kish c. 2800 BC, preserved in later king lists. There are texts written entirely in Old Akkadian dating from c. 2500 BC. Use of Old Akkadian was at its peak during the rule of Sargon the Great (c. 2334–2279 BC), but even then most administrative tablets continued to be written in Sumerian, the language used by the scribes. Gelb and Westenholz differentiate three stages of Old Akkadian: that of the pre-Sargonic era, that of the Akkadian empire, and that of the Ur III period that followed it. Akkadian and Sumerian coexisted as vernacular languages for about one thousand years, but by around 1800 BC, Sumerian was becoming more of a literary language familiar mainly only to scholars and scribes. Thorkild Jacobsen

Thorkild Peter Rudolph Jacobsen (; 7 June 1904 – 2 May 1993) was a renowned Danish historian specializing in Assyriology and Sumerian literature. He was one of the foremost scholars on the ancient Near East.

Biography

Thorkild Peter Rudolph Ja ...

has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre- and post-Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a "Semitic vs. Sumerian" conflict. However, it is certain that Akkadian was also briefly imposed on neighboring parts of Elam that were previously conquered, by Sargon.

Gutian period

c. 2193–2119 BC (middle chronology)2nd Dynasty of Lagash

c. 2200–2110 BC (middle chronology)

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of

c. 2200–2110 BC (middle chronology)

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of Gutians

The Guti () or Quti, also known by the derived exonyms Gutians or Guteans, were a nomadic people of West Asia, around the Zagros Mountains (Modern Iran) during ancient times. Their homeland was known as Gutium ( Sumerian: ,''Gu-tu-umki'' or ,'' ...

, another native Sumerian ruler, Gudea

Gudea ( Sumerian: , ''Gu3-de2-a'') was a ruler ('' ensi'') of the state of Lagash in Southern Mesopotamia, who ruled circa 2080–2060 BC (short chronology) or 2144-2124 BC ( middle chronology). He probably did not come from the city, but had mar ...

of Lagash, rose to local prominence and continued the practices of the Sargonic kings' claims to divinity.

The previous Lagash dynasty, Gudea and his descendants also promoted artistic development and left a large number of archaeological artifacts.

"Neo-Sumerian" Ur III period

Later, the Third Dynasty of Ur under

Later, the Third Dynasty of Ur under Ur-Nammu

Ur-Nammu (or Ur-Namma, Ur-Engur, Ur-Gur, Sumerian: , ruled c. 2112 BC – 2094 BC middle chronology, or possibly c. 2048–2030 BC short chronology) founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries ...

and Shulgi

Shulgi ( dŠulgi, formerly read as Dungi) of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC (Middle Chronology) or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC (Short Chronology). His accomplishme ...

(c. 2112–2004 BC, middle chronology), whose power extended as far as southern Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

, has been erroneously called a "Sumerian renaissance" in the past. Already, however, the region was becoming more Semitic than Sumerian, with the resurgence of the Akkadian-speaking Semites in Assyria and elsewhere, and the influx of waves of Semitic Martu (Amorites

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied lar ...

), who were to found several competing local powers in the south, including Isin

Isin (, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. Excavations have shown that it was an important city-state in the past.

History of archaeological research

Ishan al-Bahriyat was visited ...

, Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

, Eshnunna

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia 12.6 miles northwest of Tell Agrab and 15 miles northwest of Tell Ishchali. Although situated in the ...

and later, Babylonia. The last of these eventually came to briefly dominate the south of Mesopotamia as the Babylonian Empire

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

, just as the Old Assyrian Empire had already done in the north from the late 21st century BC. The Sumerian language continued as a sacerdotal language taught in schools in Babylonia and Assyria, much as Latin was used in the Medieval period, for as long as cuneiform was used.

Fall and transmission

This period is generally taken to coincide with a major shift in population from southern Mesopotamia toward the north. Ecologically, the agricultural productivity of the Sumerian lands was being compromised as a result of rising salinity.Soil salinity

Soil salinity is the salt (chemistry), salt content in the soil; the process of increasing the salt content is known as salinization. Salts occur naturally within soils and water. Salination can be caused by natural processes such as mineral wea ...

in this region had been long recognized as a major problem. Poorly drained irrigated soils, in an arid climate with high levels of evaporation, led to the buildup of dissolved salts in the soil, eventually reducing agricultural yields severely. During the Akkadian and Ur III

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

phases, there was a shift from the cultivation of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

to the more salt-tolerant barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

, but this was insufficient, and during the period from 2100 BC to 1700 BC, it is estimated that the population in this area declined by nearly three-fifths. This greatly upset the balance of power within the region, weakening the areas where Sumerian was spoken, and comparatively strengthening those where Akkadian was the major language. Henceforth, Sumerian would remain only a literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to includ ...

and liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

language, similar to the position occupied by Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

in medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

Europe.

Following an Elamite invasion and sack of Ur during the rule of Ibbi-Sin

Ibbi-Sin ( sux, , ), son of Shu-Sin, was king of Sumer and Akkad and last king of the Ur III dynasty, and reigned c. 2028–2004 BCE ( Middle chronology) or possibly c. 1964–1940 BCE (Short chronology). During his rei ...

(c. 2028–2004 BC), Sumer came under Amorite rule (taken to introduce the Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pr ...

). The independent Amorite states of the 20th to 18th centuries are summarized as the " Dynasty of Isin" in the Sumerian king list, ending with the rise of Babylonia under Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

c. 1800 BC.

Later rulers who dominated Assyria and Babylonia occasionally assumed the old Sargonic title "King of Sumer and Akkad", such as Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria after c. 1225 BC.

Population

Uruk, one of Sumer's largest cities, has been estimated to have had a population of 50,000–80,000 at its height; given the other cities in Sumer, and the large agricultural population, a rough estimate for Sumer's population might be 0.8 million to 1.5 million. Theworld population

In demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded 8 billion in November 2022. It took over 200,000 years of human prehistory and history for th ...

at this time has been estimated at 27 million.

The Sumerians spoke a language isolate

Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families. Korean and Basque are two of the most common examples. Other language isolates include Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, and Haida in North America. The nu ...

, but a number of linguists have claimed to be able to detect a substrate language of unknown classification beneath Sumerian because names of some of Sumer's major cities are not Sumerian, revealing influences of earlier inhabitants. However, the archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

shows clear uninterrupted cultural continuity from the time of the early Ubaid period

The Ubaid period (c. 6500–3700 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Wo ...

(5300–4700 BC C-14) settlements in southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerian people who settled here farmed the lands in this region that were made fertile by silt deposited by the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

.

Some archaeologists have speculated that the original speakers of ancient Sumerian may have been farmers, who moved down from the north of Mesopotamia after perfecting irrigation agriculture there. The Ubaid period pottery of southern Mesopotamia has been connected via Choga Mami

Choga Mami is a Samarran settlement site in Diyala province in Eastern Iraq in the Mandali region. It shows the first canal irrigation in operation at about 6000 BCE.

The site, about 70 miles northeast of Baghdad, has been dated to the late 6th ...

transitional ware to the pottery of the Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional ar ...

period culture (c. 5700–4900 BC C-14) in the north, who were the first to practice a primitive form of irrigation agriculture along the middle Tigris River and its tributaries. The connection is most clearly seen at Tell el-'Oueili

Tell el-'Oueili (also Awayli) is a tell, or ancient settlement mound, located in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. The site was excavated between 1976 and 1989 by French archaeologists under the direction of Jean-Louis Huot. The excavations hav ...

near Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

, excavated by the French in the 1980s, where eight levels yielded pre-Ubaid pottery resembling Samarran ware. According to this theory, farming peoples spread down into southern Mesopotamia because they had developed a temple-centered social organization for mobilizing labor and technology for water control, enabling them to survive and prosper in a difficult environment.

Others have suggested a continuity of Sumerians, from the indigenous hunter-fisherfolk traditions, associated with the bifacial assemblages found on the Arabian littoral. Juris Zarins

Juris Zarins (Zariņš) (born 1945, in Germany) is an American-Latvian archaeologist and professor at Missouri State University, who specializes in the Middle East.

Biography

Zarins is ethnically Latvian, but was born in Germany at the end of ...

believes the Sumerians may have been the people living in the Persian Gulf region before it flooded at the end of the last Ice Age.

Culture

Social and family life

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. Vases and dishes of stone were made in imitation of those of clay."

* "A feathered head-dress was worn. Beds, stools and chairs were used, with carved legs resembling those of an ox. There were fire-places and fire-altars."

* "Knives, drills, wedges and an instrument that looks like a saw were all known. While spears, bows, arrows, and daggers (but not swords) were employed in war."

* "Tablets were used for writing purposes. Daggers with metal blades and wooden handles were worn, and copper was hammered into plates, while necklaces or collars were made of gold."

* "Time was reckoned in lunar months."

There is considerable evidence concerning Sumerian music. Lyres and flutes were played, among the best-known examples being the Lyres of Ur

The Lyres of Ur or Harps of Ur are a group of four stringed instruments excavated in a fragmentary condition at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in modern Iraq from 1922 onwards. They date back to the Early Dynastic III Period of Mesopotamia, between ...

.

Inscriptions describing the reforms of king Urukagina of Lagash (c. 2350 BC) say that he abolished the former custom of polyandry

Polyandry (; ) is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wives" ...

in his country, prescribing that a woman who took multiple husbands be stoned with rocks upon which her crime had been written.

Sumerian culture was male-dominated and stratified. The Code of Ur-Nammu

The Code of Ur-Nammu is the oldest known law code surviving today. It is from Mesopotamia and is written on tablets, in the Sumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to ...

, the oldest such codification yet discovered, dating to the Ur III, reveals a glimpse at societal structure in late Sumerian law. Beneath the ''lu-gal'' ("great man" or king), all members of society belonged to one of two basic strata: The "''lu''" or free person, and the slave (male, ''arad''; female ''geme''). The son of a ''lu'' was called a ''dumu-nita'' until he married. A woman (''munus'') went from being a daughter (''dumu-mi''), to a wife (''dam''), then if she outlived her husband, a widow (''numasu'') and she could then remarry another man who was from the same tribe.

Marriages were usually arranged by the parents of the bride and groom; engagements were usually completed through the approval of contracts recorded on clay tablets. These marriages became legal as soon as the groom delivered a bridal gift to his bride's father. One Sumerian proverb describes the ideal, happy marriage through the mouth of a husband who boasts that his wife has borne him eight sons and is still eager to have sex.

The Sumerians generally seem to have discouraged premarital sex. Neither Sumerian nor Akkadian had a word exactly corresponding to the English word 'virginity

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

', and the concept was expressed descriptively, for example as ''a/é-nu-gi4-a'' (Sum.)/''la naqbat'' (Akk.) 'un-deflowered', or ''giš nunzua'', 'never having known a penis'. It is unclear whether terms such as ''šišitu'' in Akkadian medical texts indicate the hymen, but it appears that the intactness of the hymen was much less relevant to assessing a woman's virginity than in later cultures of the Near East, and most assessments of virginity depended on the woman's own account.

From the earliest records, the Sumerians had very relaxed attitudes toward sex and their sexual mores were determined not by whether a sexual act was deemed immoral, but rather by whether or not it made a person ritually unclean. The Sumerians widely believed that masturbation

Masturbation is the sexual stimulation of one's own genitals for sexual arousal or other sexual pleasure, usually to the point of orgasm. The stimulation may involve hands, fingers, everyday objects, sex toys such as vibrators, or combinat ...

enhanced sexual potency, both for men and for women, and they frequently engaged in it, both alone and with their partners. The Sumerians did not regard anal sex

Anal sex or anal intercourse is generally the insertion and thrusting of the erect penis into a person's anus, or anus and rectum, for sexual pleasure.Sepages 270–271for anal sex information, anpage 118for information about the clitoris. ...

as taboo either. ''Entu'' priestesses were forbidden from producing offspring and frequently engaged in anal sex as a method of birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

.

Prostitution existed but it is not clear if sacred prostitution did.

Language and writing

The most important archaeological discoveries in Sumer are a large number ofclay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a sty ...

s written in cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-s ...

. Sumerian writing is considered to be a great milestone in the development of humanity's ability to not only create historical records but also in creating pieces of literature, both in the form of poetic epics and stories as well as prayers and laws.

Although the writing system was first hieroglyphic using ideograms, logosyllabic

In a written language, a logogram, logograph, or lexigraph is a written character that represents a word or morpheme. Chinese characters (pronounced ''hanzi'' in Mandarin, '' kanji'' in Japanese, '' hanja'' in Korean) are generally logograms, ...

cuneiform soon followed.

Triangular or wedge-shaped reeds were used to write on moist clay. A large body of hundreds of thousands of texts in the Sumerian language have survived, including personal and business letters, receipts, lexical lists

The cuneiform lexical lists are a series of ancient Mesopotamian glossaries which preserve the semantics of Sumerograms, their phonetic value and their Akkadian or other language equivalents. They are the oldest literary texts from Mesopotamia ...

, laws, hymns, prayers, stories, and daily records. Full libraries of clay tablets have been found. Monumental inscriptions and texts on different objects, like statues or bricks, are also very common. Many texts survive in multiple copies because they were repeatedly transcribed by scribes in training. Sumerian continued to be the language of religion and law in Mesopotamia long after Semitic speakers had become dominant.

A prime example of cuneiform writing would be a lengthy poem that was discovered in the ruins of Uruk. The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' was written in the standard Sumerian cuneiform. It tells of a king from the early Dynastic II period named Gilgamesh or "Bilgamesh" in Sumerian. The story relates the fictional adventures of Gilgamesh and his companion, Enkidu

Enkidu ( sux, ''EN.KI.DU10'') was a legendary figure in ancient Mesopotamian mythology, wartime comrade and friend of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Their exploits were composed in Sumerian poems and in the Akkadian ''Epic of Gilgamesh'', writte ...

. It was laid out on several clay tablets and is thought to be the earliest known surviving example of fictional literature.

The Sumerian language is generally regarded as a language isolate

Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families. Korean and Basque are two of the most common examples. Other language isolates include Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, and Haida in North America. The nu ...

in linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Ling ...

because it belongs to no known language family; Akkadian, by contrast, belongs to the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages

The Afroasiatic languages (or Afro-Asiatic), also known as Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic, and sometimes also as Afrasian, Erythraean or Lisramic, are a language family of about 300 languages that are spoken predominantly in the geographic ...

. There have been many failed attempts to connect Sumerian to other language families

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ''ancestral language'' or ''parental language'', called the proto-language of that family. The term "family" reflects the tree model of language origination in hi ...

. It is an agglutinative language

An agglutinative language is a type of synthetic language with morphology that primarily uses agglutination. Words may contain different morphemes to determine their meanings, but all of these morphemes (including stems and affixes) tend to rem ...

; in other words, morpheme

A morpheme is the smallest meaningful Constituent (linguistics), constituent of a linguistic expression. The field of linguistics, linguistic study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology (linguistics), morphology.

In English, morphemes are ...

s ("units of meaning") are added together to create words, unlike analytic languages where morphemes are purely added together to create sentences. Some authors have proposed that there may be evidence of a substratum

In linguistics, a stratum (Latin for "layer") or strate is a language that influences or is influenced by another through contact. A substratum or substrate is a language that has lower power or prestige than another, while a superstratum or sup ...

or adstratum language for geographic features and various crafts and agricultural activities, called variously Proto-Euphratean or Proto Tigrean, but this is disputed by others.

Understanding Sumerian texts today can be problematic. Most difficult are the earliest texts, which in many cases do not give the full grammatical structure of the language and seem to have been used as an "aide-mémoire

Aide-mémoire (, "memory aid") is a French loanword meaning "a memory-aid; a reminder or memorandum, especially a book or document serving this purpose".

In international relations, an aide-mémoire is a proposed agreement or negotiating text c ...

" for knowledgeable scribes.

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC,Woods C. 200“Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian”

. In S.L. Sanders (ed) ''Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture'': 91–120 Chicago but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Babylonia and Assyria until the 1st century AD.

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

(London)

Cuneiform tablet- administrative account with entries concerning malt and barley groats MET DP293245.jpg, Cuneiform tablet about administrative account with entries concerning malt and barley groats; 3100–2900 BC; clay; 6.8 x 4.5 x 1.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

(New York City)

Bill of sale Louvre AO3766.jpg, Bill of sale of a field and house, from Shuruppak

Shuruppak ( sux, , "the healing place"), modern Tell Fara, was an ancient Sumerian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. Shuruppak was dedicated to ...

; c. 2600 BC; height: 8.5 cm, width: 8.5 cm, depth: 2 cm; Louvre

Stele of Vultures detail 02.jpg, ''Stele of the Vultures

The Stele of the Vultures is a monument from the Early Dynastic IIIb period (2600–2350 BC) in Mesopotamia celebrating a victory of the city-state of Lagash over its neighbour Umma. It shows various battle and religious scenes and is named aft ...

''; c. 2450 BC; limestone; found in 1881 by Édouard de Sarzec in Girsu