Stoic philosophy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stoicism is a school of

Stoicism is a school of

DateFormat = yyyy

ImageSize = width:1000 height:250

PlotArea = left:15 right:10 bottom:20 top:0

Colors =

id:bleuclair value:rgb(0.56,0.56,0.86)

id:rouge value:red

id:rougeclair value:rgb(0.86,0.56,0.56)

id:bleu value:rgb(0.76,0.76,0.96)

id:grilleMinor value:rgb(0.86,0.86,0.86)

id:grilleMajor value:rgb(0.56,0.56,0.56)

id:protohistoire value:rgb(1,0.7,0.7)

id:noir value:black

id:canvas value:rgb(0.97,0.97,0.97)

id:Holo value:rgb(0.4,0.8,0.7)

id:PSup value:rgb(0.5,1,0.5)

id:PMoy value:rgb(0.6,1,0.6)

id:PInf value:rgb(0.7,1,0.7) # vert clair

id:Plio value:rgb(0.8,1,0.8) # vert p�le

id:gris value:gray(0.80)

id:grilleMajor value:rgb(0.80,0.80,0.80)

id:Timeperiod value:red

id:Timeperiod2 value:rgb(0.86,0.56,0.56)

Period = from:-400 till:300

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal format:yyyy

AlignBars = justify

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:50 start:-400 gridcolor:grilleMinor

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:50 start:-400 gridcolor:grilleMajor

BackgroundColors = canvas:canvas bars:canvas

BarData=

bar:Timeperiod

barset:auteurs

Define $marquerouge = text:"*" textcolor:rouge shift:(0,-3) fontsize:10

PlotData=

width:15 fontsize:M textcolor:noir align:center

# Époques

bar:Timeperiod color:Timeperiod shift:(0,-3)

from:start till:end color:gris # Arrière plan

from:-400 till:300 text: "The Stoics" color:Timeperiod2

# auteurs

width:6 align:left fontsize:M shift:(5,-5) anchor:till

barset:auteurs

from:-335 till:-264 text:"

Beginning around 301 BCE,

Beginning around 301 BCE,  Scholars usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases:

# Early Stoa, from Zeno's founding to

Scholars usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases:

# Early Stoa, from Zeno's founding to

by

Stoic theology is a

Stoic theology is a

excerpts

* Hall, Ron

''Secundum Naturam (According to Nature)''

Stoic Therapy, LLC, 2021. * Inwood, Brad (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to The Stoics'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) * Lachs, John, ''Stoic Pragmatism'' (Indiana University Press, 2012) * Long, A. A., ''Stoic Studies'' (Cambridge University Press, 1996; repr. University of California Press, 2001) * Robertson, Donald, ''The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy'' (London: Karnac, 2010) * Robertson, Donald

''How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius''

'New York: St. Martin's Press, 2019. * Sellars, John, ''Stoicism'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006) * Stephens, William O., ''Stoic Ethics: Epictetus and Happiness as Freedom'' (London: Continuum, 2007) * Strange, Steven (ed.), ''Stoicism: Traditions and Transformations'' (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004) * Zeller, Eduard; Reichel, Oswald J., ''The Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics'', Longmans, Green, and Co., 1892

The Stoic Therapy eLibrary

The Stoic Library

*

BBC Radio 4's In Our Time programme on Stoicism

(requires Flash)

The Stoic Registry (formerly New Stoa) :Online Stoic Community

Modern Stoicism (Stoic Week and Stoicon)

The Four Stoic Virtues

{{Authority control Ancient Greece Ancient Rome History of philosophy Philosophy of life Virtue Virtue ethics

Stoicism is a school of

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy is a time-frame for Western philosophy and Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period. It is purely external and encompasses disparate intellectual content. There is no single philosophical school or c ...

founded by Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek ἀρετή arete_(moral_virtue).html"_;"title="'arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''_is_an_approach_to_ethics_that_treats_the_concept_of_virtue.html" ;"title="arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''.html" ; ...

informed by its system of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

and its views on the natural world, asserting that the practice of virtue is both necessary and sufficient to achieve (happiness, ): one flourishes by living an ethical

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

life. The Stoics identified the path to with a life spent practicing the cardinal virtues

The cardinal virtues are four virtues of mind and character in both classical philosophy and Christian theology. They are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. They form a virtue theory of ethics. The term ''cardinal'' comes from the ...

and living in accordance with nature.

The Stoics are especially known for teaching that "virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is morality, moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is Value (ethics), valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that sh ...

is the only good" for human beings, and that external things, such as health, wealth, and pleasure, are not good or called in themselves (''adiaphora

Adiaphoron (; plural: adiaphora; from the Greek (pl. ), meaning "not different or differentiable") is the negation of ''diaphora'', "difference".

In Cynicism, adiaphora represents indifference to the s of life. In Pyrrhonism, it indicates thin ...

'') but have value as "material for virtue to act upon". Alongside Aristotelian ethics

Aristotle first used the term '' ethics'' to name a field of study developed by his predecessors Socrates and Plato. In philosophy, ethics is the attempt to offer a rational response to the question of how humans should best live. Aristotle rega ...

, the Stoic tradition forms one of the major founding approaches to virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek ἀρετή arete_(moral_virtue).html"_;"title="'arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''_is_an_approach_to_ethics_that_treats_the_concept_of_virtue.html" ;"title="arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''.html" ; ...

. The Stoics also held that certain destructive emotions resulted from errors of judgment, and they believed people should aim to maintain a will (called ''prohairesis

Prohairesis ( grc, προαίρεσις; variously translated as "moral character", "will", "volition", "choice", "intention", or "moral choice") is a fundamental concept in the Stoic philosophy of Epictetus. It represents the choice involved in g ...

'') that is "in accordance with nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

". Because of this, the Stoics thought the best indication of an individual's philosophy was not what a person said but how a person behaved. To live a good life, one had to understand the rules of the natural order since they thought everything was rooted in nature.

Many Stoics—such as Seneca and Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

—emphasized that because "virtue is sufficient for happiness

Happiness, in the context of mental or emotional states, is positive or pleasant emotions ranging from contentment to intense joy. Other forms include life satisfaction, well-being, subjective well-being, flourishing and eudaimonia.

...

", a sage would be emotionally resilient to misfortune. This belief is similar to the meaning of the phrase "stoic calm", though the phrase does not include the traditional Stoic view that only a sage can be considered truly free and that all moral corruptions are equally vicious.

Stoicism flourished throughout the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

world until the 3rd century CE, and among its adherents was Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

. It experienced a decline after Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

became the state religion in the 4th century CE. Since then, it has seen revivals, notably in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

( Neostoicism) and in the contemporary era ( modern Stoicism).

Name

Origins

Stoicism was originally known as Zenonism, after the founderZeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

. However, this name was soon dropped, likely because the Stoics did not consider their founders to be perfectly wise and to avoid the risk of the philosophy becoming a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

.

The name ''Stoicism'' derives from the '' Stoa Poikile'' (Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

: ἡ ποικίλη στοά), or "painted porch", a colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or cur ...

decorated with mythic and historical battle scenes on the north side of the Agora

The agora (; grc, ἀγορά, romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Greek city-states. It is the best representation of a city-state's response to accommodate the social and political order o ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

where Zeno and his followers gathered to discuss their ideas.

Sometimes Stoicism is therefore referred to as "The Stoa", or the philosophy of "The Porch".

Modern usage

The word ''stoic'' commonly refers to someone who is indifferent to pain, pleasure, grief, or joy. The modern usage as a "person who represses feelings or endures patiently" was first cited in 1579 as anoun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, ...

and in 1596 as an adjective

In linguistics, an adjective ( abbreviated ) is a word that generally modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives were considered one of the ...

. In contrast to the term '' Epicurean'', the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''SEP'') combines an online encyclopedia of philosophy with peer-reviewed publication of original papers in philosophy, freely accessible to Internet users. It is maintained by Stanford University. E ...

''s entry on Stoicism notes, "the sense of the English adjective 'stoical' is not utterly misleading with regard to its philosophical origins".

Basic tenets

The Stoics provided a unified account of the world, constructed from ideals oflogic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

, monistic

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

physics, and naturalistic ethics. Of these, they emphasized ethics as the main focus of human knowledge, though their logical theories were of more interest for later philosophers.

Stoicism teaches the development of self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotion

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is currently no scientific consensus on a definitio ...

s; the philosophy holds that becoming a clear and unbiased thinker allows one to understand the universal reason (''logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Aris ...

''). Stoicism's primary aspect involves improving the individual's ethical and moral well-being: "''Virtue'' consists in a ''will'' that is in agreement with Nature".Russell, Bertrand. ''A History of Western Philosophy,'' p. 254 This principle also applies to the realm of interpersonal relationships; "to be free from anger, envy, and jealousy",Russell, Bertrand. ''A History of Western Philosophy'', p. 264 and to accept even slaves as "equals of other men, because all men alike are products of nature".Russell, Bertrand. ''A History of Western Philosophy'', p. 253.

The Stoic ethic espouses a deterministic

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and cons ...

perspective; in regard to those who lack Stoic virtue, Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; grc-gre, Κλεάνθης; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxe ...

once opined that the wicked man is "like a dog tied to a cart, and compelled to go wherever it goes". A Stoic of virtue, by contrast, would amend his will to suit the world and remain, in the words of Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

, "sick and yet happy, in peril and yet happy, dying and yet happy, in exile and happy, in disgrace and happy", thus positing a "completely autonomous" individual will and at the same time a universe that is "a rigidly deterministic single whole". This viewpoint was later described as " Classical Pantheism" (and was adopted by Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

).

History

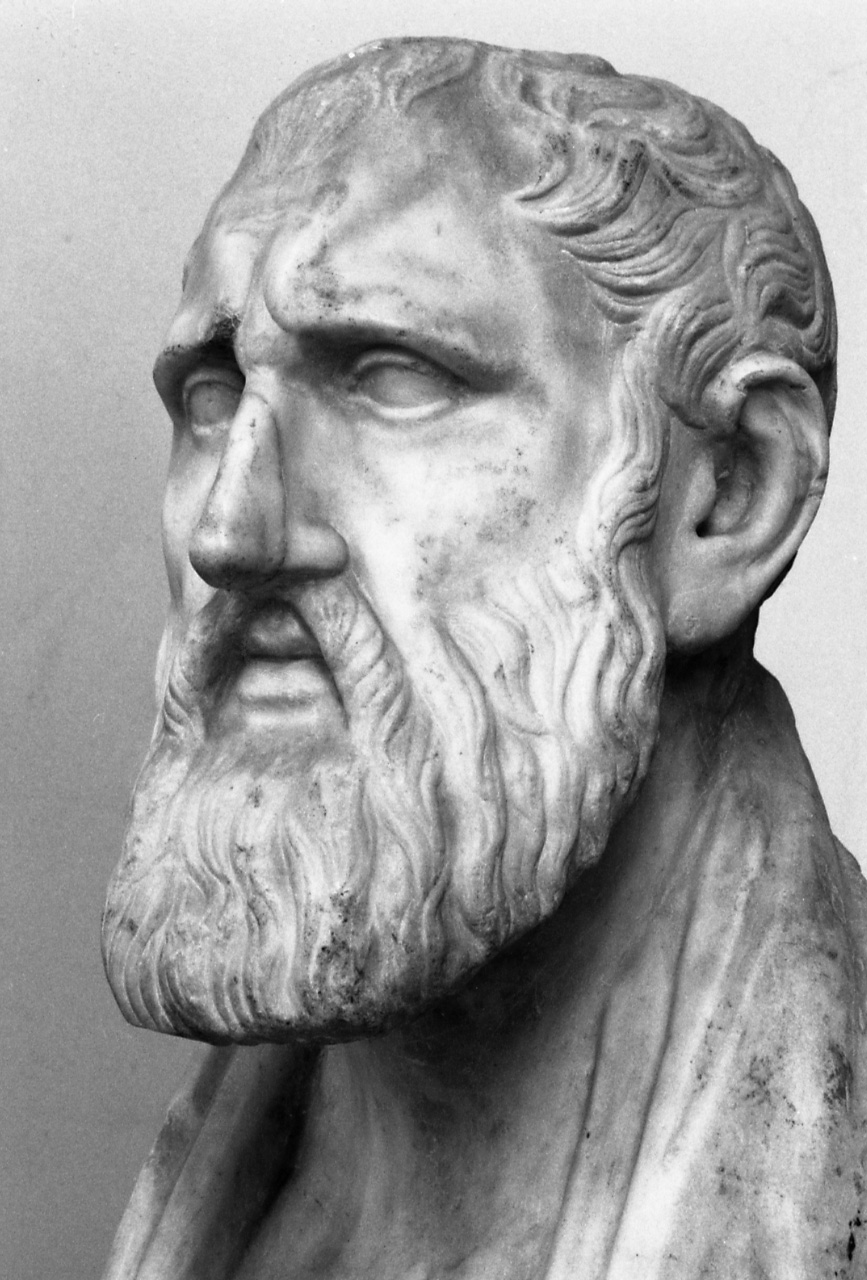

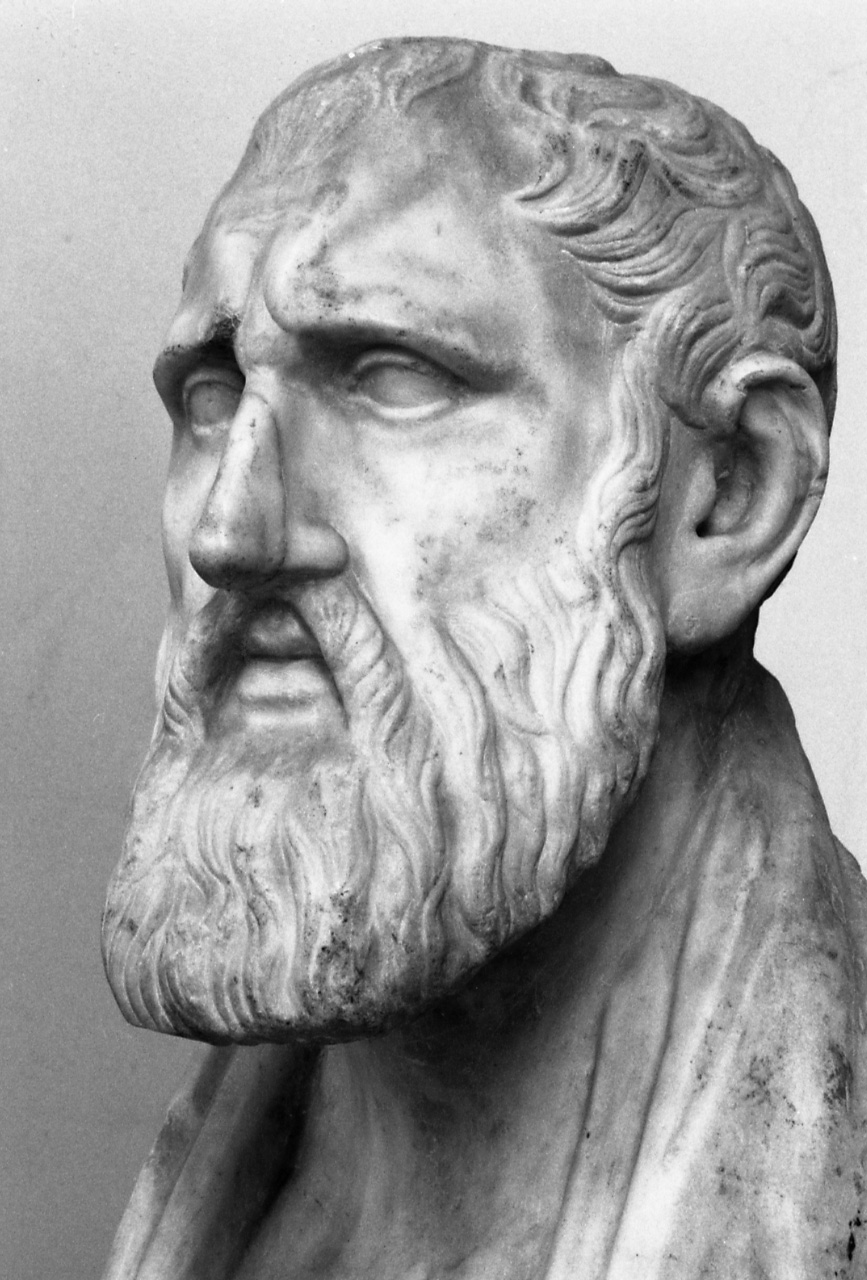

Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

" color:Pinf

from:-330 till:-232 text:"Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; grc-gre, Κλεάνθης; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxe ...

" color:Pinf

from:-281 till:-205 text:"Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

" color:Pinf

from:-240 till:-152 text:" Diogenes of Babylon" color:Pinf

from:-210 till:-129 text:"Antipater of Tarsus

Antipater of Tarsus ( el, Ἀντίπατρος ὁ Ταρσεύς; died 130/129 BC) was a Stoic philosopher. He was the pupil and successor of Diogenes of Babylon as leader of the Stoic school, and was the teacher of Panaetius. He wrote works on ...

" color:Pinf

from:-180 till:-100 text:"Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, Παναίτιος, Panaítios; – ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic ...

" color:Pinf

from:-140 till:-51 text:"Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

" color:Pinf

from:-4 till:65 text:" Seneca" color:Pinf

from:25 till:95 text:" Musonius Rufus" color:Pinf

from:55 till:135 text:"Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

" color:Pinf

from:121 till:180 text:"Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

" color:Pinf

Beginning around 301 BCE,

Beginning around 301 BCE, Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

taught philosophy at the '' Stoa Poikile'' ("Painted Porch"), from which his philosophy got its name. Unlike the other schools of philosophy, such as the Epicureans

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by ...

, Zeno chose to teach his philosophy in a public space, which was a colonnade overlooking the central gathering place of Athens, the Agora

The agora (; grc, ἀγορά, romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Greek city-states. It is the best representation of a city-state's response to accommodate the social and political order o ...

.

Zeno's ideas developed from those of the Cynics, whose founding father, Antisthenes

Antisthenes (; el, Ἀντισθένης; 446 366 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and a pupil of Socrates. Antisthenes first learned rhetoric under Gorgias before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates. He adopted and developed the ethical side ...

, had been a disciple of Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

. Zeno's most influential follower was Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

, who was responsible for molding what is now called Stoicism. Later Roman Stoics focused on promoting a life in harmony within the universe over which one has no direct control.

Scholars usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases:

# Early Stoa, from Zeno's founding to

Scholars usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases:

# Early Stoa, from Zeno's founding to Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

# Middle Stoa, including Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, Παναίτιος, Panaítios; – ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic ...

and Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

# Late Stoa, including Musonius Rufus, Seneca, Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

, and Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

No complete works survived from the first two phases of Stoicism. Only Roman texts from the Late Stoa survived.

Stoicism became the foremost popular philosophy among the educated elite in the Hellenistic world and the Roman Empire to the point where, in the words of Gilbert Murray, "nearly all the successors of Alexander ..professed themselves Stoics".

Logic

Propositional logic

Diodorus Cronus

Diodorus Cronus ( el, Διόδωρος Κρόνος; died c. 284 BC) was a Greek philosopher and dialectician connected to the Megarian school. He was most notable for logic innovations, including his master argument formulated in response to A ...

, who was one of Zeno's teachers, is considered the philosopher who first introduced and developed an approach to logic now known as propositional logic

Propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. It deals with propositions (which can be true or false) and relations b ...

, which is based on statements or propositions, rather than terms, differing greatly from Aristotle's term logic

In philosophy, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, ...

. Later, Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

developed a system that became known as Stoic logic and included a deductive system, Stoic Syllogistic, which was considered a rival to Aristotle's Syllogistic (see Syllogism

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be tru ...

). New interest in Stoic logic came in the 20th century, when important developments in logic were based on propositional logic. Susanne Bobzien

Susanne Bobzien (born 1960) is a German-born philosopherWho'sWho in America 2012, 64th Edition whose research interests focus on philosophy of logic and language, determinism and freedom, and ancient philosophy. She currently is senior research ...

wrote, "The many close similarities between Chrysippus's philosophical logic and that of Gottlob Frege

Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege (; ; 8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925) was a German philosopher, logician, and mathematician. He was a mathematics professor at the University of Jena, and is understood by many to be the father of analytic p ...

are especially striking".''Ancient Logic''by

Susanne Bobzien

Susanne Bobzien (born 1960) is a German-born philosopherWho'sWho in America 2012, 64th Edition whose research interests focus on philosophy of logic and language, determinism and freedom, and ancient philosophy. She currently is senior research ...

. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Bobzien also notes that, "Chrysippus wrote over 300 books on logic, on virtually any topic logic today concerns itself with, including speech act

In the philosophy of language and linguistics, speech act is something expressed by an individual that not only presents information but performs an action as well. For example, the phrase "I would like the kimchi; could you please pass it to me? ...

theory, sentence analysis, singular and plural expressions, types of predicates, indexicals, existential propositions, sentential connectives, negation

In logic, negation, also called the logical complement, is an operation that takes a proposition P to another proposition "not P", written \neg P, \mathord P or \overline. It is interpreted intuitively as being true when P is false, and false ...

s, disjunctions, conditionals

Conditional (if then) may refer to:

*Causal conditional, if X then Y, where X is a cause of Y

*Conditional probability, the probability of an event A given that another event B has occurred

*Conditional proof, in logic: a proof that asserts a co ...

, logical consequence

Logical consequence (also entailment) is a fundamental concept in logic, which describes the relationship between statements that hold true when one statement logically ''follows from'' one or more statements. A valid logical argument is on ...

, valid argument

In logic, specifically in deductive reasoning, an argument is valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false. It is not required for a valid argument to have ...

forms, theory of deduction, propositional logic, modal logic

Modal logic is a collection of formal systems developed to represent statements about necessity and possibility. It plays a major role in philosophy of language, epistemology, metaphysics, and natural language semantics. Modal logics extend ot ...

, tense logic, epistemic logic, logic of suppositions, logic of imperatives, ambiguity and logical paradox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically u ...

es".

Categories

The Stoics held that allbeing

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities e ...

s (ὄντα)—though not all things (τινά)—are material

Material is a substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties, or on their geolo ...

. Besides the existing beings they admitted four incorporeals (asomata): time, place, void, and sayable. They were held to be just 'subsisting' while such a status was denied to universals. Thus, they accepted Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

's idea (as did Aristotle) that if an object is hot, it is because some part of a universal heat body had entered the object. But, unlike Aristotle, they extended the idea to cover all accidents

An accident is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans. The term ''accident'' implies that nobody should be blamed, but the event may have been caused by unrecognized or unaddressed risks. Most researcher ...

. Thus, if an object is red, it would be because some part of a universal red body had entered the object.

They held that there were four categories.

# Substance (ὑποκείμενον): The primary matter, formless substance, (''ousia'') that things are made of

# Quality (ποιόν): The way matter is organized to form an individual object; in Stoic physics, a physical ingredient (''pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for " spirit" or "soul". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is ...

'': air or breath), which informs the matter

# Somehow disposed (πως ἔχον): Particular characteristics, not present within the object, such as size, shape, action, and posture

# Somehow disposed in relation to something (πρός τί πως ἔχον): Characteristics related to other phenomena, such as the position of an object within time and space relative to other objects

Stoics outlined what we have control over categories of our own action, thoughts and reaction. The opening paragraph of the '' Enchiridion'' states the categories as: "Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in a word, whatever are not our own actions." These suggest a space that is within our own control.

Epistemology

The Stoics propounded thatknowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is distin ...

can be attained through the use of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

. Truth

Truth is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth 2005 In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as belief ...

can be distinguished from fallacy

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning, or "wrong moves," in the construction of an argument which may appear stronger than it really is if the fallacy is not spotted. The term in the Western intellectual tradition was intr ...

—even if, in practice, only an approximation can be made. According to the Stoics, the sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system re ...

s constantly receive sensations: pulsations that pass from objects through the senses to the mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

, where they leave an impression in the imagination

Imagination is the production or simulation of novel objects, sensations, and ideas in the mind without any immediate input of the senses. Stefan Szczelkun characterises it as the forming of experiences in one's mind, which can be re-creations ...

( phantasiai) (an impression arising from the mind was called a phantasma).

The mind has the ability to judge (συγκατάθεσις, ''synkatathesis'')—approve or reject—an impression, enabling it to distinguish a true representation of reality from one that is false. Some impressions can be assented to immediately, but others can achieve only varying degrees of hesitant approval, which can be labeled belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to tak ...

or opinion ('' doxa''). It is only through reason that we gain clear comprehension and conviction (''katalepsis

''Katalepsis'' ( el, κατάληψις, "grasping") in Stoic philosophy, that meant comprehension. To the Stoic philosophers, ''katalepsis'' was an important premise regarding one's state of mind as it relates to grasping fundamental philosophi ...

''). Certain

Certainty (also known as epistemic certainty or objective certainty) is the epistemic property of beliefs which a person has no rational grounds for doubting. One standard way of defining epistemic certainty is that a belief is certain if and o ...

and true knowledge (''episteme

In philosophy, episteme (; french: épistémè) is a term that refers to a principle system of understanding (i.e., knowledge), such as scientific knowledge or practical knowledge. The term comes from the Ancient Greek verb grc, ἐπῐ́ ...

''), achievable by the Stoic sage, can be attained only by verifying the conviction with the expertise of one's peers and the collective judgment of humankind.

Physics

According to the Stoics, theUniverse

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

is a material

Material is a substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties, or on their geolo ...

reasoning substance (''logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Aris ...

''), known as God or Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

, which was divided into two classes: the active and the passive. The passive substance is matter, which "lies sluggish, a substance ready for any use, but sure to remain unemployed if no one sets it in motion". The active substance, which can be called Fate or Universal Reason (''logos''), is an intelligent aether or primordial fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames ...

, which acts on the passive matter:

Everything is subject to the laws of Fate, for the Universe acts according to its own nature, and the nature of the passive matter it governs. The soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

s of humans and animals are emanations from this primordial Fire, and are, likewise, subject to Fate:

Individual souls are perishable by nature, and can be "transmuted and diffused, assuming a fiery nature by being received into the ''seminal reason'' ("logos spermatikos

Glossary of terms commonly found in Stoic philosophy.

A

;adiaphora: ἀδιάφορα: indifferent things, neither good nor bad.

;agathos: ἀγαθός: good, proper object of desire.

;anthrôpos: ἄνθρωπος: human being, used by Epictet ...

") of the Universe". Since right Reason is the foundation of both humanity and the universe, it follows that the goal of life is to live according to Reason, that is, to live a life according to Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

.

Stoic theology is a

Stoic theology is a fatalistic

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are t ...

and naturalistic pantheism

Naturalistic pantheism, also known as scientific pantheism, is a form of pantheism. It has been used in various ways such as to relate God or divinity with concrete things, determinism,Paul Tillich: Theologian of the Boundaries by Paul Tillich, Mar ...

: God is never fully transcendent but always immanent

The doctrine or theory of immanence holds that the divine encompasses or is manifested in the material world. It is held by some philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence. Immanence is usually applied in monotheistic, panthe ...

, and identified with Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

. Abrahamic religions

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish tradition ...

personalize God as a world-creating entity, but Stoicism equates God with the totality of the universe; according to Stoic cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

, which is very similar to the Hindu conception of existence, there is no absolute start to time, as it is considered infinite and cyclic. Similarly, space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consi ...

and the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

have neither start nor end, rather they are cyclical. The current Universe is a phase in the present cycle, preceded by an infinite number of Universes, doomed to be destroyed (" ekpyrōsis", ''conflagration'') and re-created again, and to be followed by another infinite number of Universes. Stoicism considers all existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval Latin ''existentia/exsistentia' ...

as cyclical, the cosmos as eternally self-creating and self-destroying (see also Eternal return

Eternal return (german: Ewige Wiederkunft; also known as eternal recurrence) is a concept that the universe and all existence and energy has been recurring, and will continue to recur in a self similar form an infinite number of times across i ...

).

Stoicism, just like Indian religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

such as Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, and Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

, does not posit a beginning or end to the Universe.Ferguson, Everett. ''Backgrounds of Early Christianity''. 2003, p. 368. According to the Stoics, the ''logos'' was the active reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

or ''anima mundi

The ''anima mundi'' ( Greek: , ) or world soul is, according to several systems of thought, an intrinsic connection between all living beings, which relates to the world in much the same way as the soul is connected to the human body.

Although ...

'' pervading and animating the entire Universe. It was conceived as material and is usually identified with God or Nature. The Stoics also referred to the ''seminal reason'' ("logos spermatikos

Glossary of terms commonly found in Stoic philosophy.

A

;adiaphora: ἀδιάφορα: indifferent things, neither good nor bad.

;agathos: ἀγαθός: good, proper object of desire.

;anthrôpos: ἄνθρωπος: human being, used by Epictet ...

"), or the law of generation in the Universe, which was the principle of the active reason working in inanimate matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic part ...

. Humans, too, each possess a portion of the divine ''logos'', which is the primordial Fire and reason that controls and sustains the Universe.

The first philosophers to explicitly describe nominalist arguments were the Stoics, especially Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

.

Ethics

Ancient Stoics are often misunderstood because the terms they used pertained to different concepts than today. The word "stoic" has since come to mean "unemotional" or indifferent to pain because Stoic ethics taught freedom from "passion" by following "reason". The Stoics did not seek to extinguish emotions; rather, they sought to transform them by a resolute " askēsis", that enables a person to develop clear judgment and inner calm. Logic, reflection, and focus were the methods of such self-discipline, temperance is split into self-control, discipline, and modesty. Borrowing from the Cynics, the foundation of Stoic ethics is that good lies in the state of the soul itself; in wisdom and self-control. Stoic ethics stressed the rule: "Follow where reason leads". One must therefore strive to be free of thepassions

''Passions'' is an American television soap opera that originally aired on NBC from July 5, 1999, to September 7, 2007, and on DirecTV's The 101 Network from September 17, 2007, to August 7, 2008. Created by screenwriter James E. Reilly and ...

, bearing in mind that the ancient meaning of ''pathos

Pathos (, ; plural: ''pathea'' or ''pathê''; , for " suffering" or "experience") appeals to the emotions and ideals of the audience and elicits feelings that already reside in them. Pathos is a term used most often in rhetoric (in which it is ...

'' (plural ''pathe'') translated here as ''passion'' was "anguish" or "suffering", that is, "passively" reacting to external events, which is somewhat different from the modern use of the word. Terms used in Stoicism related to ''pathos'' include ''propathos'' or instinctive reaction (e.g., turning pale and trembling when confronted by physical danger) and ''eupathos'', which is the mark of the Stoic sage (''sophos''). The ''eupatheia'' are feelings that result from the correct judgment in the same way that passions result from incorrect judgment. The idea was to be free of suffering

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual. Suffering is the basic element that makes up the negative valence of a ...

through ''apatheia

Apatheia ( el, ἀπάθεια; from ''a-'' "without" and ''pathos'' "suffering" or "passion"), in Stoicism, refers to a state of mind in which one is not disturbed by the passions. It might better be translated by the word equanimity than the wor ...

'' (Greek: ; literally, "without passion") or peace of mind, where peace of mind was understood in the ancient sense—being objective or having "clear judgment" and the maintenance of equanimity

Equanimity (Latin: ''æquanimitas'', having an even mind; ''aequus'' even; ''animus'' mind/soul) is a state of psychological stability and composure which is undisturbed by experience of or exposure to emotions, pain, or other phenomena that may ...

in the face of life's highs and lows.

For the Stoics, reason meant using logic and understanding the processes of nature—the logos or universal reason, inherent in all things. According to reason and virtue, living according to reason and virtue is to live in harmony with the divine order of the universe, in recognition of the common reason and essential value of all people.

The four cardinal virtues

The cardinal virtues are four virtues of mind and character in both classical philosophy and Christian theology. They are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. They form a virtue theory of ethics. The term ''cardinal'' comes from the ...

('' aretai'') of Stoic philosophy is a classification derived from the teachings of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(''Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

'' IV. 426–35):

* Wisdom

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowledg ...

(Greek: φρόνησις "''phronesis''" or σοφία "''sophia''", Latin: ''prudentia'' or sapientia)

* Courage

Courage (also called bravery or valor) is the choice and willingness to confront agony, pain, danger, uncertainty, or intimidation. Valor is courage or bravery, especially in battle.

Physical courage is bravery in the face of physical pain, ...

(Greek: ανδρεία "''andreia''", Latin: ''fortitudo'')

* Justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

(Greek: δικαιοσύνη "''dikaiosyne''", Latin: ''iustitia'')

* Temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

(Greek: σωφροσύνη ''" sophrosyne''", Latin: ''temperantia'')

Following Socrates, the Stoics held that unhappiness and evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

are the results of human ignorance of the reason in nature. If someone is unkind, it is because they are unaware of their own universal reason, which leads to the conclusion of unkindness. The solution to evil and unhappiness then is the practice of Stoic philosophy: to examine one's own judgments and behavior and determine where they diverge from the universal reason of nature.

The Stoics accepted that suicide was permissible for the wise person in circumstances that might prevent them from living a virtuous life.Don E. Marietta, (1998), ''Introduction to ancient philosophy'', pp. 153–54. Sharpe Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

held that accepting life under tyranny would have compromised Cato's self-consistency (''constantia'') as a Stoic and impaired his freedom to make the honorable moral choices. Suicide could be justified if one fell victim to severe pain or disease, but otherwise suicide would usually be seen as a rejection of one's social duty.William Braxton Irvine, (2009), ''A guide to the good life: the ancient art of Stoic joy'', p. 200. Oxford University Press

The doctrine of "things indifferent"

In philosophical terms, things that are indifferent are outside the application of moral law—that is without tendency to either promote or obstruct moral ends. Actions that are neither required nor forbidden by the moral law, or that do not affectmorality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of co ...

, are called morally indifferent. The doctrine of things indifferent (, ''adiaphora

Adiaphoron (; plural: adiaphora; from the Greek (pl. ), meaning "not different or differentiable") is the negation of ''diaphora'', "difference".

In Cynicism, adiaphora represents indifference to the s of life. In Pyrrhonism, it indicates thin ...

'') arose in the Stoic school as a corollary

In mathematics and logic, a corollary ( , ) is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another ...

of its diametric opposition of virtue and vice ( ''kathekon

Kathēkon ( el, καθῆκον) (plural: ''kathēkonta'' el, καθήκοντα) is a Greek concept, forged by the founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium. It may be translated as "appropriate behaviour", "befitting actions", or "convenient action fo ...

ta'', "convenient actions", or actions in accordance with nature; and ἁμαρτήματα ''hamartemata'', mistakes). As a result of this dichotomy

A dichotomy is a partition of a whole (or a set) into two parts (subsets). In other words, this couple of parts must be

* jointly exhaustive: everything must belong to one part or the other, and

* mutually exclusive: nothing can belong simul ...

, a large class of objects were left unassigned and thus regarded as indifferent.

Eventually three sub-classes of "things indifferent" developed: things to prefer because they assist life according to nature; things to avoid because they hinder it; and things indifferent in the narrower sense. The principle of ''adiaphora'' was also common to the Cynics. Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

revived the doctrine of things indifferent during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

.

Spiritual exercise

Philosophy for a Stoic is not just a set of beliefs or ethical claims; it is a way of life involving constant practice and training (or " askēsis"). Stoic philosophical and spiritual practices includedlogic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

, Socratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue ( grc, Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the p ...

and self-dialogue, contemplation of death, mortality salience, training attention to remain in the present moment (similar to mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of purposely bringing one's attention to the present-moment experience without evaluation, a skill one develops through meditation or other training. Mindfulness derives from ''sati'', a significant element of Hind ...

and some forms of Buddhist meditation

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are ''bhāvanā'' ("mental development") and '' jhāna/dhyāna'' (mental training resulting in a calm and ...

), and daily reflection on everyday problems and possible solutions e.g. with journaling. Philosophy for a Stoic is an active process of constant practice and self-reminder.

In his ''Meditations

''Meditations'' () is a series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from AD 161 to 180, recording his private notes to himself and ideas on Stoic philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius wrote the 12 books of the ''Meditations'' in Koine ...

'', Marcus Aurelius defines several such practices. For example, in Book II.I:

Say to yourself in the early morning: I shall meet today ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, uncharitable men. All of the ignorance of real good and ill ... I can neither be harmed by any of them, for no man will involve me in wrong, nor can I be angry with my kinsman or hate him; for we have come into the world to work together ...Prior to Aurelius, Epictetus in his '' Discourses,'' distinguished between three types of act: judgment, desire, and inclination. According to philosopher

Pierre Hadot

Pierre Hadot (; ; 21 February 1922 – 24 April 2010) was a French philosopher and historian of philosophy specializing in ancient philosophy, particularly Neoplatonism.

Life

In 1944, Hadot was ordained, but following Pope Pius XII’s enc ...

, Epictetus identifies these three acts with logic, physics and ethics respectively. Hadot writes that in the ''Meditations'', "Each maxim develops either one of these very characteristic ''topoi'' .e., acts or two of them or three of them."

Seamus Mac Suibhne has described the practices of spiritual exercises as influencing those of reflective practice

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one's actions so as to take a critical stance or attitude towards one's own practice and that of one's peers, engaging in a process of continuous adaptation and learning. According to one defini ...

. Many parallels between Stoic spiritual exercises and modern cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social intervention that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions (suc ...

have been identified.

Stoics were also known for consolatory orations, which were part of the '' consolatio'' literary tradition. Three such consolations by Seneca have survived.

Stoics commonly employ ‘The View from Above’, reflecting on society and otherness in guided visualization, aiming to gain a "bigger picture", to see ourselves in context relevant to others, to see others in the context of the world, to see ourselves in the context of the world to help determine our role and the importance of happenings.

Marcus Aurelius, ''Meditations'', in Book 7.48 it is stated;

A fine reflection from Plato. One who would converse about human beings should look on all things earthly as though from some point far above, upon herds, armies, and agriculture, marriages and divorces, births and deaths, the clamour of law courts, deserted wastes, alien peoples of every kind, festivals, lamentations, and markets, this intermixture of everything and ordered combination of opposites.

Love and sexuality

Stoics consideredsexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied wit ...

an element within the law of nature that was not to be good or bad by itself, but condemned passionate desire as something to be avoided. Early exponents differed significantly from late stoics in their view of romantic love

Romance or romantic love is a feeling of love for, or a strong attraction towards another person, and the courtship behaviors undertaken by an individual to express those overall feelings and resultant emotions.

The ''Wiley Blackwell Encyc ...

and sexual relationships.

Zeno advocated for a republic ruled by love and not by law, where marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

would be abolished, wives would be held in common, and eroticism would be practiced with both boys and girls with educative purposes, to develop virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is morality, moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is Value (ethics), valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that sh ...

in the loved ones. However, he didn't condemn marriage per se, considering it equally a natural occurrence. He regarded same sex relationships

A same-sex relationship is a romantic or sexual relationship between people of the same sex. '' Same-sex marriage'' refers to the institutionalized recognition of such relationships in the form of a marriage; civil unions may exist in countrie ...

positively, and maintained that wise men should "have carnal knowledge no less and no more of a favorite than of a non-favorite, nor of a female than of a male." Zeno favored love over desire, clarifying that the ultimate goal of sexuality should be virtue and friendship.

Among later stoics, Epictetus maintained homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

and heterosexual sex as equivalent in this field, and condemned only the kind of desire that led one to act against judgement. However, contemporaneous positions generally advanced towards equating sexuality with passion, and although they were still not hostile to sexual relationships by themselves, they nonetheless believed those should be limited in order to retain self-control. Musonius espoused the only natural kind of sex was that meant for procreation, defending a companionate form of marriage between man and woman, and considered relationships solely undergone for pleasure or affection as unnatural. This view was ultimately influential in other currents of thought.

Social philosophy

A distinctive feature of Stoicism is itscosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings are members of a single community. Its adherents are known as cosmopolitan or cosmopolite. Cosmopolitanism is both prescriptive and aspirational, believing humans can and should be " world citizen ...

; according to the Stoics, all people are manifestations of the one universal spirit and should live in brotherly love and readily help one another. In the '' Discourses'', Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

comments on man's relationship with the world: "Each human being is primarily a citizen of his own commonwealth; but he is also a member of the great city of gods and men, whereof the city political is only a copy." This sentiment echoes that of Diogenes of Sinope

Diogenes ( ; grc, Διογένης, Diogénēs ), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (, ) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy). He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea ...

, who said, "I am not an Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

or a Corinthian, but a citizen of the world."

They held that external differences, such as rank and wealth, are of no importance in social relationships. Instead, they advocated the brotherhood of humanity and the natural equality of all human beings. Stoicism became the most influential school of the Greco-Roman world, and produced a number of remarkable writers and personalities, such as Cato the Younger

Marcus Porcius Cato "Uticensis" ("of Utica"; ; 95 BC – April 46 BC), also known as Cato the Younger ( la, Cato Minor), was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the ...

and Epictetus.

In particular, they were noted for their urging of clemency

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

toward slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s. Seneca in his Letter 47 exhorted, "Kindly remember that he whom you call your slave sprang from the same stock, is smiled upon by the same skies, and on equal terms with yourself breathes, lives, and dies."

Influence on Christianity

In St. Ambrose of Milan's ''Duties'', "The voice is the voice of a Christian bishop, but the precepts are those ofZeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

." Regarding what he called "the Divine Spirit", Maxwell Staniforth wrote:

Cleanthes, wishing to give more explicit meaning to Zeno's 'creative fire', had been the first to hit upon the term ''pneuma'', or 'spirit', to describe it. Like fire, this intelligent 'spirit' was imagined as a tenuous substance akin to a current of air or breath, but essentially possessing the quality of warmth; it was immanent in the universe as God, and in man as the soul and life-giving principle. Clearly, it is not a long step from this to the 'Holy Spirit' of Christian theology, the 'Lord and Giver of life', visibly manifested as tongues of fire at Pentecost and ever since associated—in the Christian as in the Stoic mind—with the ideas of vital fire and beneficient warmth.Regarding the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, Staniforth wrote:

Again in the doctrine of the Trinity, the ecclesiastical conception of Father, Word, and Spirit finds its germ in the different Stoic names of the Divine Unity. Thus Seneca, writing of the supreme Power which shapes the universe, states, 'This Power we sometimes call the All-ruling God, sometimes the incorporeal Wisdom, sometimes the Holy Spirit, sometimes Destiny.' The Church had only to reject the last of these terms to arrive at its own acceptable definition of the Divine Nature; while the further assertion 'these three are One', which the modern mind finds paradoxical, was no more than commonplace to those familiar with Stoic notions.The

apostle Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

met with Stoics during his stay in Athens, reported in . In his letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alpha ...

, Paul reflected heavily from his knowledge of Stoic philosophy, using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

converts in their understanding of Christianity. This is seen, for example, in 1 Corinthians 11

1 Corinthians 11 is the eleventh chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It was authored by Paul the Apostle and Sosthenes in Ephesus. In this chapter, Paul writes on the conduct of Christians w ...

, in which Paul enjoins the ordinance

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* ...

of headcovering with a cloth veil by appealing to nature in a ''reductio ad absurdum

In logic, (Latin for "reduction to absurdity"), also known as (Latin for "argument to absurdity") or ''apagogical arguments'', is the form of argument that attempts to establish a claim by showing that the opposite scenario would lead to absu ...

'': "if there is something especially suitable about a woman’s head being covered, then she should be glad to wear a headcovering in ''addition'' to the long hair." Stoic influence can also be seen in the works of St. Ambrose, Marcus Minucius Felix

__NOTOC__

Marcus Minucius Felix (died c. 250 AD in Rome) was one of the earliest of the Latin apologists for Christianity.

Nothing is known of his personal history, and even the date at which he wrote can be only approximately ascertained as bet ...

, and Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

.

The Fathers of the Church

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

regarded Stoicism as a "pagan philosophy"; Agathias. ''Histories,'' 2.31. nonetheless, early Christian writers employed some of the central philosophical concepts of Stoicism. Examples include the terms "logos", "virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is morality, moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is Value (ethics), valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that sh ...

", "Spirit", and "conscience

Conscience is a cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's moral philosophy or value system. Conscience stands in contrast to elicited emotion or thought due to associations based on immediate sens ...

". But the parallels go well beyond the sharing and borrowing of terminology. Both Stoicism and Christianity assert an inner freedom in the face of the external world, a belief in human kinship with Nature or God, a sense of the innate depravity—or "persistent evil"—of humankind, and the futility and temporary nature of worldly possessions and attachments. Both encourage ''Ascesis'' with respect to the passions and inferior emotions, such as lust, and envy, so that the higher possibilities of one's humanity can be awakened and developed.

Stoic writings such as ''Meditations

''Meditations'' () is a series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from AD 161 to 180, recording his private notes to himself and ideas on Stoic philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius wrote the 12 books of the ''Meditations'' in Koine ...

'' by Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

have been highly regarded by many Christians throughout the centuries. The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

and Oriental Orthodox Church

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

accept the Stoic ideal of dispassion to this day.

Middle and Roman Stoics taught that sex is just within marriage, for unitive and procreative purposes only. This teaching is accepted by the Catholic Church to this day.

Saint Ambrose of Milan was known for applying Stoic philosophy to his theology.

Stoic philosophers

*Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

(332–262 BCE), founder of Stoicism and the Stoic Academy (Stoa) in Athens

* Aristo of Chios ( 260 BCE), pupil of Zeno;

* Herillus of Carthage ( 3rd century BCE)

* Cleanthes (of Assos) (330–232 BCE), second head of Stoic Academy

* Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

(280–204 BCE), third head of the academy

* Diogenes of Babylon (230–150 BCE)

* Antipater of Tarsus

Antipater of Tarsus ( el, Ἀντίπατρος ὁ Ταρσεύς; died 130/129 BC) was a Stoic philosopher. He was the pupil and successor of Diogenes of Babylon as leader of the Stoic school, and was the teacher of Panaetius. He wrote works on ...

(210–129 BCE)

* Panaetius of Rhodes

Panaetius (; grc-gre, Παναίτιος, Panaítios; – ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic do ...

(185–109 BCE)

* Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

of Apameia

* Diodotus teacher of Cicero

* Cato the Younger

Marcus Porcius Cato "Uticensis" ("of Utica"; ; 95 BC – April 46 BC), also known as Cato the Younger ( la, Cato Minor), was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the ...

(94–46 BCE)

* Seneca

* Gaius Musonius Rufus

Gaius Musonius Rufus (; grc-gre, Μουσώνιος Ῥοῦφος) was a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Ga ...

(1st century CE)

* Rubellius Plautus (33–62 CE)

* Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus

Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus (died AD 66), Roman senator, who lived in the 1st century AD. Notable for his principled opposition to the emperor Nero and his interest in Stoicism, he was the husband of Arria, who was the daughter of A. Caecina ...

(1st century CE)

* Lucius Annaeus Cornutus

Lucius Annaeus Cornutus ( grc, Ἀνναῖος Κορνοῦτος), a Stoic philosopher, flourished in the reign of Nero (c. 60 AD), when his house in Rome was a school of philosophy.

Life

Cornutus was a native of Leptis Magna in Libya, but res ...

* Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

(55–135 CE)

* Hierocles

* Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good E ...

(121–180 CE)

See also

* 4 Maccabees * Definitions of philosophy *Deixis