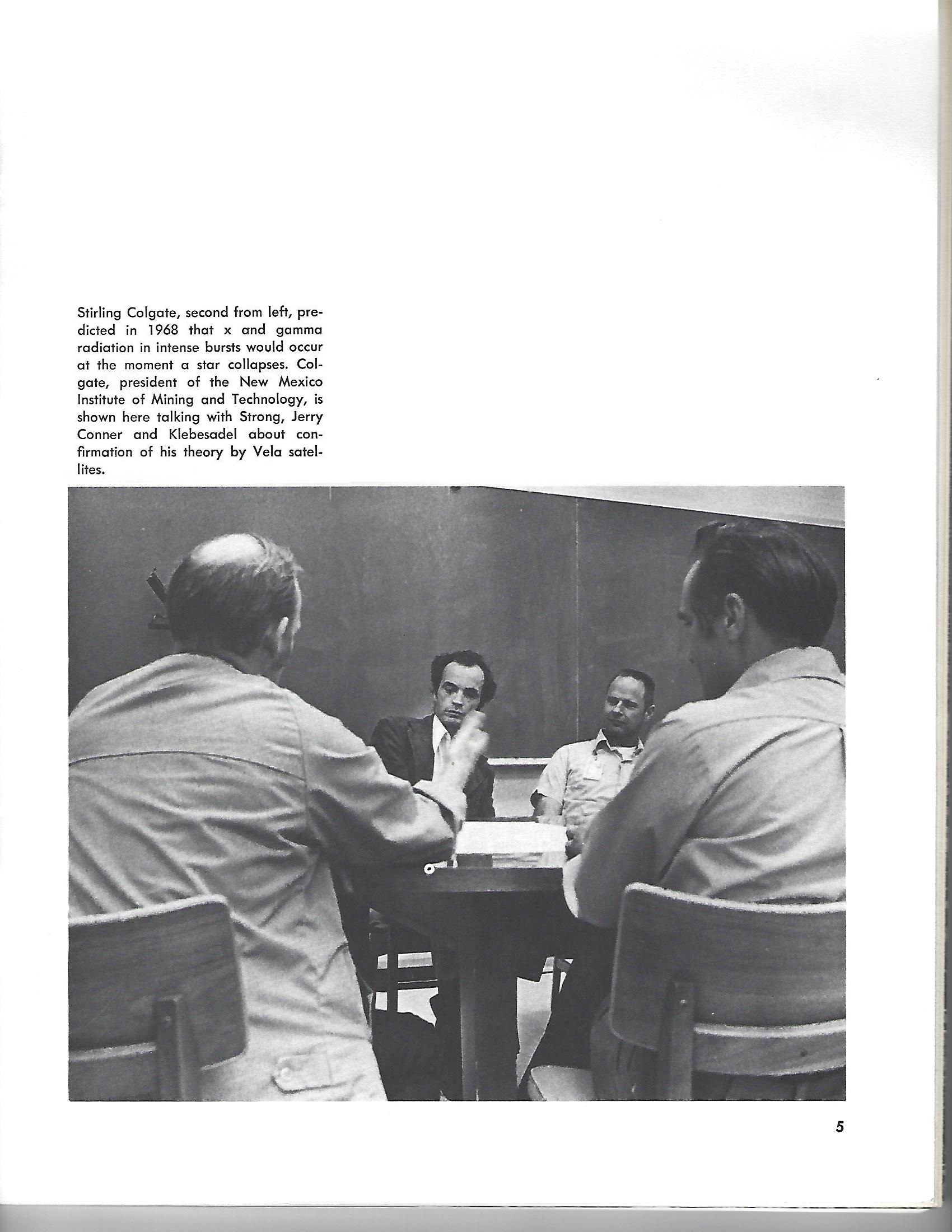

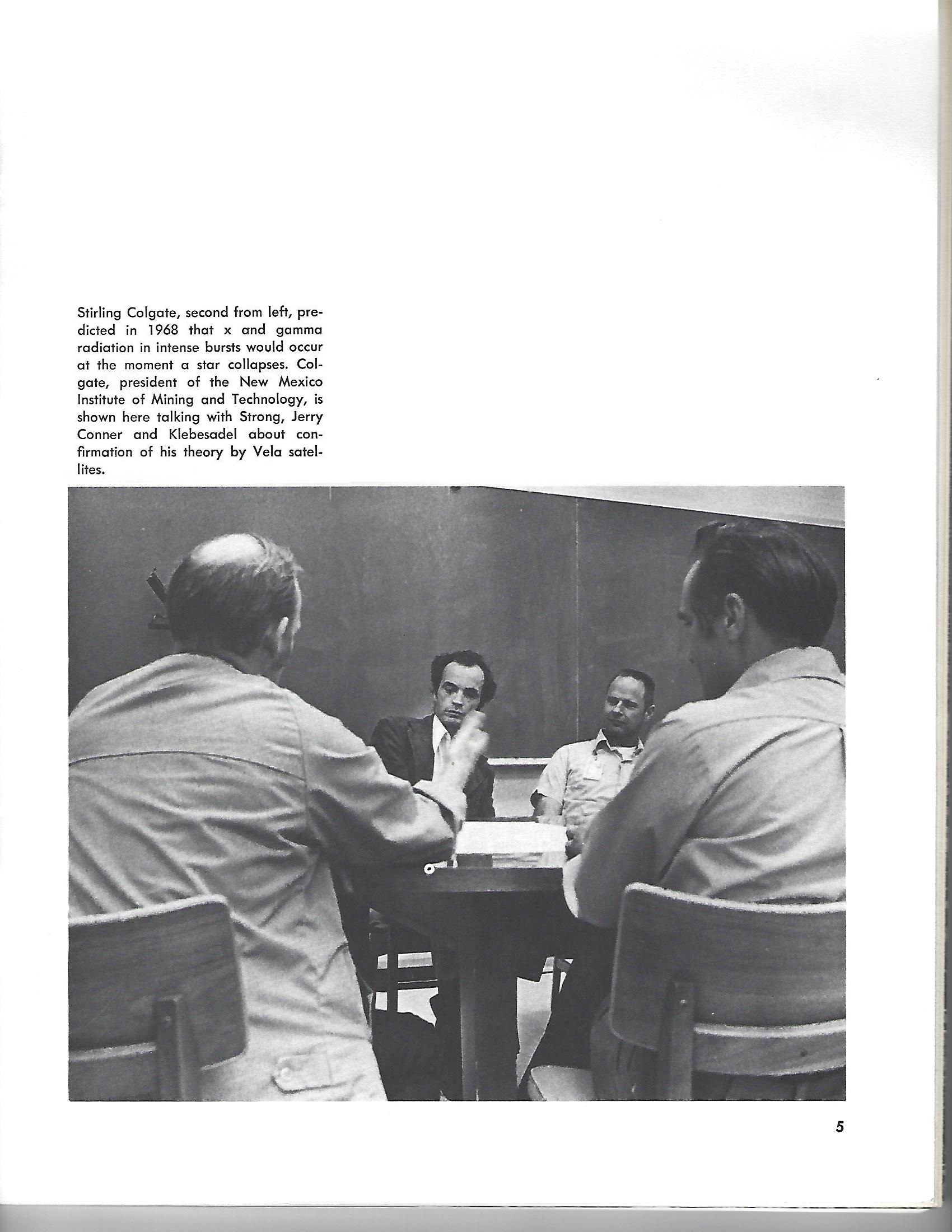

Stirling Colgate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stirling Auchincloss Colgate (; November 14, 1925 – December 1, 2013) was an American

Many of his projects had colorful names inspired by the experimental configurations and goals. Some of these included DigAs (a search for early supernova in galaxies with a remote controlled telescope in real time using an IBM 360-44 mainframe computer through a digital microwave link from the New Mexico Tech campus to the school's Langmuir Laboratory)(see the PBS NOVA episode "Death of a Star", 1987, ~ 8 minutes in),

Many of his projects had colorful names inspired by the experimental configurations and goals. Some of these included DigAs (a search for early supernova in galaxies with a remote controlled telescope in real time using an IBM 360-44 mainframe computer through a digital microwave link from the New Mexico Tech campus to the school's Langmuir Laboratory)(see the PBS NOVA episode "Death of a Star", 1987, ~ 8 minutes in),

2005 Video Interview with Stirling Auchincloss Colgate by Cynthia C. Kelly

Voices of the Manhattan Project {{DEFAULTSORT:Colgate, Stirling 1925 births 2013 deaths Cornell University College of Engineering alumni American nuclear physicists University of California, Berkeley staff New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel Santa Fe Institute people

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

and a professor emeritus of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, past president at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology

The New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology (New Mexico Tech and formerly New Mexico School of Mines) is a public university in Socorro, New Mexico. It offers over 30 bachelor of science degrees in technology, the sciences, engineering, man ...

(New Mexico Tech) from 1965 to 1974, and a scion of the Colgate toothpaste family. He was America's premier diagnostician of thermonuclear weapons

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

during the early years at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. While much of his involvement with physics is still highly classified, he made many contributions in the open literature including physics education

Physics education refers to the methods currently used to teach physics. Physics Education Research refers to an area of pedagogical research that seeks to improve those methods. Historically, physics has been taught at the high school and colle ...

and astrophysics.

Early life and education

Colgate was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

in 1925, to Henry Auchincloss and Jeanette Thurber (née Pruyn) Colgate. He attended Los Alamos Ranch School

Los Alamos Ranch School was a private ranch school for boys in the northeast corner of Sandoval County, New Mexico (since 1949, within Los Alamos County), USA, founded in 1917 near San Ildefonso Pueblo. During World War II, the school was bought ...

until 1942 when a military delegation along with input from Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

and Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation f ...

decided to close the school. Colgate and others in the class were then graduated without notice. The following year he attended Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to tea ...

to study electrical engineering.

In 1944, Colgate enlisted in the merchant marine. After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, the captain of the ship Colgate was serving on called on Colgate to "tell us what it means." At that time what he explained was strictly confidential, most of all the description of nuclear fission.

After being discharged in 1946, Colgate returned to Cornell University, where he completed a Bachelor of Science in 1948 and a PhD in nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

in 1951, then taking up a position as postdoctoral fellow at Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

.

The development of the hydrogen bomb

In 1952 he moved to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The laboratory had been recently created byEdward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

with encouragement from the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

in order to compete with Los Alamos weapons research. For the purposes of developing a hydrogen bomb, Teller assigned Colgate to the diagnostic measurements for their nuclear tests.

Colgate studied the radioactive products of an explosion which were scooped from the atmosphere by specially designed aircraft. His second job was measuring the range of energy of the neutrons and higher frequency gamma rays created by the nuclear tests.

Colgate's work required him to shuffle between Livermore and Los Alamos. During one trip to Los Alamos he met Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, whom he worked with again almost ten years later.

In the 1950s Colgate was in charge of thousands during the Bravo test, the first deliverable thermonuclear bomb, which akin to his earlier work, included the atmospheric sampling Project Ashcan. Upon the success of the detonation, Teller encouraged Colgate to begin research on thermonuclear fusion

Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or “fusing” using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible. There are two forms of thermonuclear fusion: ''uncontrolled'', in which the re ...

and .

Later career

In 1956 Colgate and colleague Montgomery H. Johnson were recruited to investigate the resultant radiation and debris from a hydrogen bomb explosion in space. They realized that theX-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

and gamma-ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically sh ...

emissions of supernovae could also set off satellites designed to detect hydrogen bomb explosions.

Colgate's supernova research during this investigation ignited his interest in astrophysics. Colgate and Johnson's first attempts to understand the mechanism of a supernova began with determining the actual cause of one. They assumed that "a shockwave from the core bounce smashes into nuclear ash plummeting inwards due to the inward tug of gravity". The shock wave would turn this matter around, heating it up, causing the supernova. However, this turned out to be wrong, as Richard H. White used computer simulations to show that the shock wave would not be strong enough to trigger the event. Colgate and White began developing models of stars on the verge of collapse. White wrote a computer program combining software used to design bombs with equations of state for a star. In discussions with a friend, Colgate found that neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

s can develop degeneracy pressure

Degenerate matter is a highly dense state of fermionic matter in which the Pauli exclusion principle exerts significant pressure in addition to, or in lieu of, thermal pressure. The description applies to matter composed of electrons, protons, ne ...

. This pressure aided the shock wave in blowing off the outer shells of an expiring star, leaving a neutron star

A neutron star is the collapsed core of a massive supergiant star, which had a total mass of between 10 and 25 solar masses, possibly more if the star was especially metal-rich. Except for black holes and some hypothetical objects (e.g. w ...

behind. While this research helped validate Chandrasekhar's work on limits, neutron stars were still purely hypothetical.

In 1959, upon the advice of Los Alamos and Livermore National Laboratories, the State Department recruited Colgate as the scientific consultant on nuclear test ban negotiations in Geneva. It was here that he proposed the detection of nuclear testing by use of spy satellites

A reconnaissance satellite or intelligence satellite (commonly, although unofficially, referred to as a spy satellite) is an Earth observation satellite or communications satellite deployed for military or intelligence applications.

Th ...

, specifically the Vela satellites. However, he also raised the possibility of false alarms caused by supernovae.

Despite encouragement by Teller to follow up on the detonation of the 50-megaton Czar bomb which the Soviet Union had just detonated, Colgate decided to continue his prior research on supernovae.

In 1966 his research with Johnson and White finally emerged in a paper carefully edited by Chandrasekhar Chandrasekhar, Chandrashekhar or Chandra Shekhar is an Indian name and may refer to a number of individuals. The name comes from the name of an incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva. In this form he married the goddess Parvati. Etymologically, the nam ...

.

Colgate went on to serve as the president of New Mexico Tech in Socorro, New Mexico from the beginning of 1965 through the end of 1974. While there he conducted research programs in astrophysics and atmospheric physics as well as leading the college.

Many of his projects had colorful names inspired by the experimental configurations and goals. Some of these included DigAs (a search for early supernova in galaxies with a remote controlled telescope in real time using an IBM 360-44 mainframe computer through a digital microwave link from the New Mexico Tech campus to the school's Langmuir Laboratory)(see the PBS NOVA episode "Death of a Star", 1987, ~ 8 minutes in),

Many of his projects had colorful names inspired by the experimental configurations and goals. Some of these included DigAs (a search for early supernova in galaxies with a remote controlled telescope in real time using an IBM 360-44 mainframe computer through a digital microwave link from the New Mexico Tech campus to the school's Langmuir Laboratory)(see the PBS NOVA episode "Death of a Star", 1987, ~ 8 minutes in), Paul Bunyan

Paul Bunyan is a giant lumberjack and folk hero in American and Canadian folklore. His exploits revolve around the tall tales of his superhuman labors, and he is customarily accompanied by Babe the Blue Ox. The character originated in the o ...

's Condom (aka PBC—a long plastic tube inflated by a B-26 bomber engine/propeller pumping charged smoke up into a thunder storm cloud), and SNORT (supernova observational radio telescope—a search for radio frequency chirps caused by the dispersive media between the receiver and the distant supernova).

From 1975 until his death, Colgate worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and was a professor emeritus at New Mexico Tech. He continued his research into supernova and received the 2006 Los Alamos medal from LANL. Colgate had a specially-designed laboratory on the New Mexico Tech campus where he continued his research until mid-2013, when he ceased work due to failing health.

In 1984 Colgate co-founded the Santa Fe Institute

The Santa Fe Institute (SFI) is an independent, nonprofit theoretical research institute located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States and dedicated to the multidisciplinary study of the fundamental principles of complex adaptive systems, inclu ...

.

Notes

Sources

* * * See chapter 6 in particular.External links

2005 Video Interview with Stirling Auchincloss Colgate by Cynthia C. Kelly

Voices of the Manhattan Project {{DEFAULTSORT:Colgate, Stirling 1925 births 2013 deaths Cornell University College of Engineering alumni American nuclear physicists University of California, Berkeley staff New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel Santa Fe Institute people