St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst, is the

The earliest parts of St Mary's church are the

The earliest parts of St Mary's church are the  Next the west porch was raised by the addition of a third storey, and the porticus side chapels were extended westward, parallel with the nave. On the third floor of the tower, on the east side, is a double triangular-headed opening into the

Next the west porch was raised by the addition of a third storey, and the porticus side chapels were extended westward, parallel with the nave. On the third floor of the tower, on the east side, is a double triangular-headed opening into the

Around AD 1200 the separate porticus were knocked through and extended westward as north and south aisles, running the length of the nave and partly overlapping the west tower. The north aisle seems to have been built first, with the south being added very slightly later. For each aisle a fine three-

Around AD 1200 the separate porticus were knocked through and extended westward as north and south aisles, running the length of the nave and partly overlapping the west tower. The north aisle seems to have been built first, with the south being added very slightly later. For each aisle a fine three- The west window of the south aisle includes some panels of

The west window of the south aisle includes some panels of

The first floor of the west tower may have had the same role as that in the

The first floor of the west tower may have had the same role as that in the

Entrance to the church is through the west porch, which now forms the lower stages of the west tower. The present west doorway is not the original, but an animal's head above it remains. Animal head label-stops with spiral decoration have been moved from outside to the inner doorway. Others form the label-stops of the chancel arch at the end of the nave. There are similar Anglo-Saxon animal heads in the parish churches of Alkborough in Lincolnshire and

Entrance to the church is through the west porch, which now forms the lower stages of the west tower. The present west doorway is not the original, but an animal's head above it remains. Animal head label-stops with spiral decoration have been moved from outside to the inner doorway. Others form the label-stops of the chancel arch at the end of the nave. There are similar Anglo-Saxon animal heads in the parish churches of Alkborough in Lincolnshire and  Inside the porch, on the ground floor over the inner doorway, is an 8th-century relief of the

Inside the porch, on the ground floor over the inner doorway, is an 8th-century relief of the

In the church is a double

In the church is a double

The Friends of Deerhurst Church

{{DEFAULTSORT:Deerhurst, Saint Mary 9th-century church buildings in England Church of England church buildings in Gloucestershire Deerhurst Saint Mary Grade I listed churches in Gloucestershire Standing Anglo-Saxon churches

Church of England parish church

A parish church in the Church of England is the church which acts as the religious centre for the people within each Church of England parish (the smallest and most basic Church of England administrative unit; since the 19th century sometimes ca ...

of Deerhurst

Deerhurst is a village and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England, about southwest of Tewkesbury. The village is on the east bank of the River Severn. The parish includes the village of Apperley and the hamlet of Deerhurst Walton. The 201 ...

, Gloucestershire, England. Much of the church is Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

. It was built in the 8th century, when Deerhurst was part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

. It is contemporary with the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the Christian Roman Empire of t ...

on mainland Europe, which may have influenced it.

The church was restored and altered in the 10th century after the Viking invasion of England. It was enlarged early in the 13th century and altered in the 14th and 15th centuries. The church has been described as "an Anglo-Saxon monument of the first order". It is a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

.

From the Anglo-Saxon era until the Dissolution of the Monasteries St Mary's was the church of a Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of ...

.

Deerhurst has a second Anglo-Saxon place of worship, the 11th-century Odda's Chapel

Odda's Chapel is a former chantry chapel at Deerhurst, Gloucestershire. It is an 11th-century late Anglo-Saxon building, completed a decade before the Norman Conquest of England.

In the 16th century the chapel ceased to be used for worship and b ...

, about 200 yards southwest of the church.

Priory

By AD 804 St Mary's was part of a Benedictine monastery at Deerhurst. In about 1060 KingEdward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

(reigned 1042–66) granted the monastery to the Abbey of St Denis in France, making it an alien priory

Alien priories were religious establishments in England, such as monasteries and convents, which were under the control of another religious house outside England. Usually the mother-house was in France.Coredon ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms'' ...

.

According to the chronicler Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

(''circa'' 1200–1259), in 1250 Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall

Richard (5 January 1209 – 2 April 1272) was an English prince who was King of the Romans from 1257 until his death in 1272. He was the second son of John, King of England, and Isabella, Countess of Angoulême. Richard was nominal Count of P ...

stayed at St Denis and bought Deerhurst Priory from the abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. Th ...

. He took over the priory, dispersed the monks and planned to build a castle at Deerhurst on the bank of the River Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

. However, the purchase was reversed and by 1264 St Denis abbey again possessed the priory.

In the 14th century England and France were at war. King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

seized alien priories in England in 1337, so that their incomes went to him instead of their mother houses in France. In 1345 the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

leased Deerhurst priory to a Thomas de Bradeston for £110 a year. In 1389 the priory was let for £200 a year to a Sir John Russell and a chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligence ...

called William Hitchcock.

By 1400 King Henry IV had restored the priory to the Abbey of St Denis. But King Henry VI

Henry VI (6 December 1421 – 21 May 1471) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. The only child of Henry V, he succeeded to the English throne at ...

seized the priory in 1443, and four years later granted it to the recently founded Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

in Buckinghamshire.

In 1461 Edward of York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

deposed the Lancastrian Henry VI and was crowned King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

. He granted Deerhurst priory to William Buckland, a monk of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. But Edward revoked the grant in 1467, claiming that Buckland had appointed only one secular chaplain, had withdrawn hospitality and had wasted the revenues of the priory.

The King granted the priory to Tewkesbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of St Mary the Virgin, Tewkesbury–commonly known as Tewkesbury Abbey–is located in the English county of Gloucestershire. A former Benedictine monastery, it is now a parish church. Considered one of the finest examples of No ...

instead, on condition that the abbot maintain a prior and four monks at Deerhurst. In 1467 the priory held the manors of Deerhurst, Coln St. Dennis, Compton, Hawe, Preston-on-Stour, Uckington, Welford-on-Avon and Wolston in Gloucestershire, Taynton with La More in Oxfordshire, and the rectories of Deerhurst and Uckington.

Tewkesbury Abbey and its priories were suppressed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Deerhurst Priory and all of its estates were surrendered to the Crown on 9 January 1540.

Architecture

Anglo-Saxon

The earliest parts of St Mary's church are the

The earliest parts of St Mary's church are the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

and chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

, which were built in the 8th century. The nave is narrow and tall: an Anglo-Saxon style seen also at Escomb

Escomb is a village on the River Wear about west of Bishop Auckland, County Durham, England. Escomb was a civil parish until 1960, when it and a number of other civil parishes in the area were dissolved. In 2001 it had a population of 358. In 2 ...

, Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the Ty ...

and Monkwearmouth

Monkwearmouth is an area of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear in North East England. Monkwearmouth is located at the north side of the mouth of the River Wear. It was one of the three original settlements on the banks of the River Wear along with Bish ...

in County Durham. The chancel was a polygonal apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

and is now ruined.

The first addition to the church was probably the west porch, which was originally of two storeys. It is longer east–west than it is north–south, and is divided into two chambers. Its walls include much herringbone masonry.

Then the first pair of rectangular two-storey porticus

A porticus, in church architecture and archaeology, is usually a small room in a church. Commonly, porticus form extensions to the north and south sides of a church, giving the building a cruciform plan. They may function as chapels, rudimentary ...

were added, either side of the east end of the nave. A second pair of porticus, west of the first, was added later. The second floor of the porch has two doorways, each with a semicircular arch. One is at the western end on the outside of the church. Over its arch are a square hood-mould with an animal's head above. This may have led to an outside gallery. The other is at the eastern end facing into the nave. It may have led to a gallery in the nave.

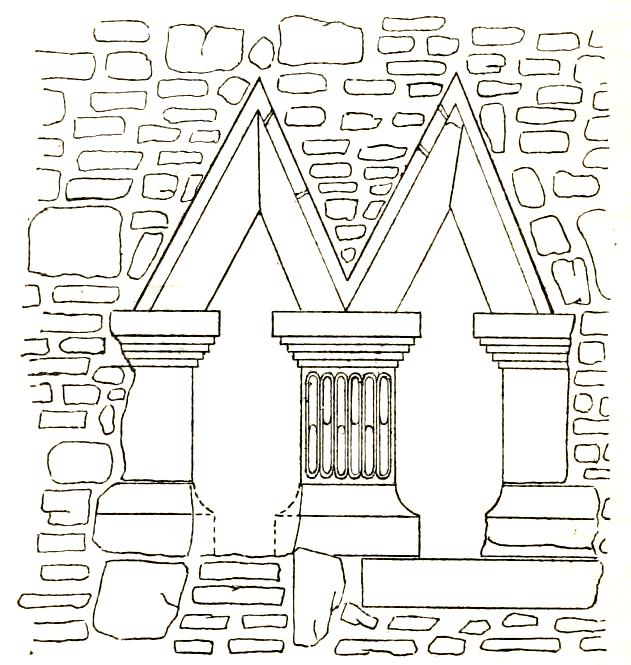

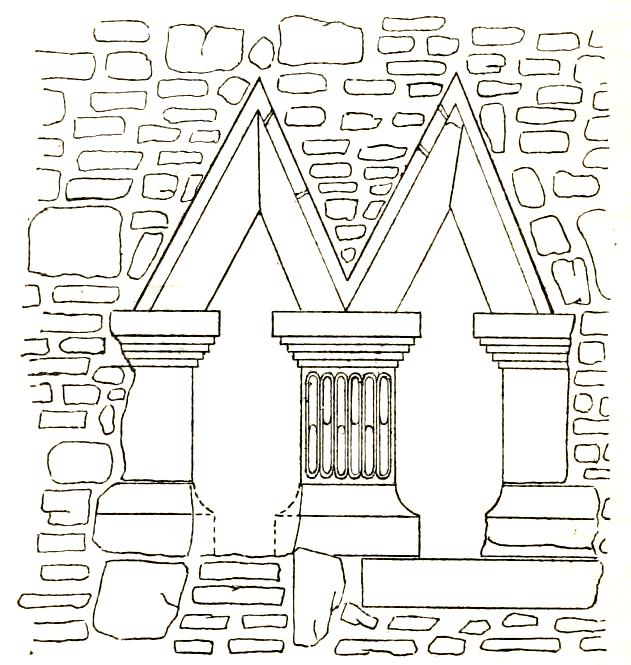

Next the west porch was raised by the addition of a third storey, and the porticus side chapels were extended westward, parallel with the nave. On the third floor of the tower, on the east side, is a double triangular-headed opening into the

Next the west porch was raised by the addition of a third storey, and the porticus side chapels were extended westward, parallel with the nave. On the third floor of the tower, on the east side, is a double triangular-headed opening into the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

with stylised capitals and fluted pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

s with reeded decoration.

Below, at first floor level, is a blocked doorway, sited off-centre, which most likely led to a gallery in the nave. Corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s just below this doorway tend to support this supposition. There is a triangular window in the east wall of the tower and each of the nave side walls at this level.

All these phases of development were completed before the Viking invasion.

John Leland (''circa'' 1503–1552) claimed that the Vikings burnt Deerhurst. After the invasion, the church was restored in or before AD 970. A fourth storey was added to the west porch, making it a tower. The upper stages of the tower have quoin

Quoins ( or ) are masonry

Masonry is the building of structures from individual units, which are often laid in and bound together by mortar; the term ''masonry'' can also refer to the units themselves. The common materials of masonry con ...

s, but not in the Anglo-Saxon long-and-short style. At the same time the present large chancel arch was inserted and the chancel may have been rebuilt.

Gothic

bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a nar ...

Early English arcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated game machine

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware

** Arcade system board, a standardized printed circuit board

* Amusement arcade, a place with arcade games

* ...

with moulded arches was inserted in the nave wall. At an unknown date the apsidal chancel was demolished and the chancel arch walled up.

Above each arcade, windows were inserted in the north and south walls of the nave to create a clerestory

In architecture, a clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey) is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, ''clerestory'' denoted an upper l ...

. But the current aisle and clerestory windows are later: Decorated Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

and late Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-c ...

.

The west window of the south aisle includes some panels of

The west window of the south aisle includes some panels of Medieval stained glass

Medieval stained glass is the coloured and painted glass of medieval Europe from the 10th century to the 16th century. For much of this period stained glass windows were the major pictorial art form, particularly in northern France, Germany a ...

. One is from about 1300–40 and is a representation of St Catherine of Alexandria

Catherine of Alexandria (also spelled Katherine); grc-gre, ἡ Ἁγία Αἰκατερίνη ἡ Μεγαλομάρτυς ; ar, سانت كاترين; la, Catharina Alexandrina). is, according to tradition, a Christian saint and virgin, ...

. Next to it is a larger panel from about 1450 which is a representation of St Alphege (''circa'' AD 953–1012). Alphege started his religious life by entering Deerhurst monastery as a boy.

Gothic Revival

William Wailes made the stained glass in the west window of the north aisle in 1853.Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient British workshops of stained-glass windows during the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (1827–1913) and Alfred Bell (1832 ...

made the stained glass in one of the north windows of the north aisle in 1861. The pulpit was also made in 1861. It was designed by the architect William Slater, who directed a restoration of the church in 1861–63.

Role of the west tower

Possible first floor chapel

The first floor of the west tower may have had the same role as that in the

The first floor of the west tower may have had the same role as that in the westwork

A westwork (german: Westwerk), forepart, avant-corps or avancorpo is the monumental, often west-facing entrance section of a Carolingian, Ottonian, or Romanesque church. The exterior consists of multiple stories between two towers. The interio ...

of a Carolingian church. Westworks had an altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in pagan ...

on the first floor, to which access was by flanking staircase tower

A staircase tower or stair tower (german: Treppenturm, also ''Stiegenturm'' or ''Wendelstein'') is a tower-like wing of a building with a circular or polygonal plan that contains a stairwell, usually a helical staircase.

History

Only a few e ...

s. South of the tower is a later Mediæval spiral staircase that used to lead to the second floor of the tower. The original staircase may have been within the tower.

The twin staircase tower arrangement was included only in the larger Anglo-Saxon churches in England (''e.g.'' possibly Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

and Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of t ...

), which have now been lost. Deerhurst may have housed an altar similarly to the Carolingian arrangement, which would account for the position of the door to the side and the triangular window, if the altar was at the centre.

Bells

The '' Regularis Concordia'', written about AD 973 as part of theEnglish Benedictine Reform

The English Benedictine Reform or Monastic Reform of the English church in the late tenth century was a religious and intellectual movement in the later Anglo-Saxon period. In the mid-tenth century almost all monasteries were staffed by secular ...

, includes instructions on how bells should be rung for the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

and holidays

A holiday is a day set aside by custom or by law on which normal activities, especially business or work including school, are suspended or reduced. Generally, holidays are intended to allow individuals to celebrate or commemorate an event or t ...

. This is about the time that the height of St Mary's west tower was increased to create the present belfry. But no Anglo-Saxon bells survive at Deerhurst.

The tower has a ring of six bells. Abel Rudhall of Gloucester

Rudhall of Gloucester was a family business of bell founders in the city of Gloucester, England, who between 1684 and 1835 cast more than 5,000 bells.

History

There had been a tradition of bell casting in Gloucester since before the 14th century. ...

cast the second and fourth bells in 1736 and the tenor bell in 1737. Thomas Rudhall cast the third bell in 1771. Thomas II Mears of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry was a business in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. At the time of the closure of its Whitechapel premises, it was the oldest manufacturing company in Great Britain. The bell foundry primarily made church bells ...

cast the fifth bell in 1826. John Taylor & Co

John Taylor Bell Foundry (Loughborough) Limited, trading as John Taylor & Co and commonly known as Taylor's Bell Foundry, Taylor's of Loughborough, or simply Taylor's, is the world's largest working bell foundry. It is located in Loughborough, ...

of Loughborough, Leicestershire cast the treble bell in 1882.

Sculpture

Entrance to the church is through the west porch, which now forms the lower stages of the west tower. The present west doorway is not the original, but an animal's head above it remains. Animal head label-stops with spiral decoration have been moved from outside to the inner doorway. Others form the label-stops of the chancel arch at the end of the nave. There are similar Anglo-Saxon animal heads in the parish churches of Alkborough in Lincolnshire and

Entrance to the church is through the west porch, which now forms the lower stages of the west tower. The present west doorway is not the original, but an animal's head above it remains. Animal head label-stops with spiral decoration have been moved from outside to the inner doorway. Others form the label-stops of the chancel arch at the end of the nave. There are similar Anglo-Saxon animal heads in the parish churches of Alkborough in Lincolnshire and Barnack

Barnack is a village and civil parish, now in the Peterborough unitary authority of the ceremonial county of Cambridgeshire, England and the historic county of Northamptonshire. Barnack is in the north-west of the unitary authority, south-east ...

in the Soke of Peterborough

The Soke of Peterborough is a historic area of England associated with the City and Diocese of Peterborough, but considered part of Northamptonshire. The Soke was also described as the Liberty of Peterborough, or Nassaburgh hundred, and comp ...

.

Inside the porch, on the ground floor over the inner doorway, is an 8th-century relief of the

Inside the porch, on the ground floor over the inner doorway, is an 8th-century relief of the Virgin and Child

In art, a Madonna () is a representation of Mary, either alone or with her child Jesus. These images are central icons for both the Catholic and Orthodox churches. The word is (archaic). The Madonna and Child type is very prevalent ...

. On the ruined apse is a 10th-century relief of an angel, showing Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

influence.

In the north aisle is the baptismal font

A baptismal font is an article of church furniture used for baptism.

Aspersion and affusion fonts

The fonts of many Christian denominations are for baptisms using a non-immersive method, such as aspersion (sprinkling) or affusion (pouring). ...

, which is one of the oldest in England. The bowl and upper part of the stem are cylindrical. The lower part of the stem is octagonal and plain, as if it were meant to slot into the floor. The bowl is decorated with a broad band of double trumpet-spirals, with narrower bands of vine scrolls above and below.

This is the only known example of a double spiral pattern on a font. However, similar decoration is found on 9th-century English manuscripts and on a pendant found in the Trewhiddle Hoard in Cornwall. On this basis Sir Alfred Clapham

Sir Alfred William Clapham, (1883 – 1950) was a British scholar of Romanesque architecture. He was Secretary of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) and President of the Society of Antiquaries.

Early life

Alfred Clapham ...

(1885–1950) dated the font to the 9th century.

Monuments

In the church is a double

In the church is a double monumental brass

A monumental brass is a type of engraved sepulchral memorial, which in the 13th century began to partially take the place of three-dimensional monuments and effigies carved in stone or wood. Made of hard latten or sheet brass, let into the pav ...

to Sir John Cassey (or Cassy) and his wife (''circa'' 1400). Cassey was Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

to King Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father d ...

. In the chancel are early 16th-century brasses of two ladies. A plaque commemorates the composer George Butterworth

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth, MC (12 July 18855 August 1916) was an English composer who was best known for the orchestral idyll '' The Banks of Green Willow'' and his song settings of A. E. Housman's poems from ''A Shropshire Lad''.

Early y ...

, MC (1885–1916), whose grandfather, the Rev George Butterworth, had been vicar of St Mary's in the previous century. The plaque was erected by the composer's father, Sir Alexander Butterworth.

Burials

*Æthelmund

Æthelmund, an Anglo-Saxon noble, was Ealdorman of Hwicce in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. He was killed in 802 at the Battle of Kempsford by Ealdorman Weohstan and the levies of West Saxon Wiltshire.Williams, Smyth & Kirby, ''A Biograp ...

, Ealdorman

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

of Hwicce

Hwicce () was a tribal kingdom in Anglo-Saxon England. According to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the kingdom was established in 577, after the Battle of Deorham. After 628, the kingdom became a client or sub-kingdom of Mercia as a result of th ...

, may be buried in the church.

In the churchyard are war graves

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

of two First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

soldiers: Pte Lewis Cox, RAMC

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) is a specialist corps in the British Army which provides medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace. The RAMC, the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, the Royal Army Dental Corps ...

, who died in 1917 and Pte George Chalk, RASC, who died in 1919.

*Elizabeth Brugge (daughter of Thomas Brugge, 5th Baron Chandos

Thomas Brugge, de jure 5th Baron Chandos (1427 – 30 January 1493), was an English peer.

Origins

Thomas Brugge was born in Coberley, Gloucestershire, England son of Giles Brugge, 4th Baron Chandos and Catherine Clifford, daughter of James ...

)

See also

*List of English abbeys, priories and friaries serving as parish churches

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby union ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

The Friends of Deerhurst Church

{{DEFAULTSORT:Deerhurst, Saint Mary 9th-century church buildings in England Church of England church buildings in Gloucestershire Deerhurst Saint Mary Grade I listed churches in Gloucestershire Standing Anglo-Saxon churches