St. Oliver Plunkett on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

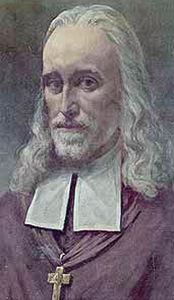

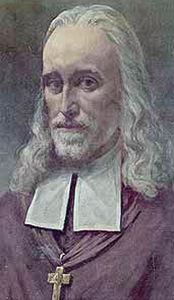

Oliver Plunkett (or Oliver Plunket) ( ga, Oilibhéar Pluincéid), (1 November 1625 – 1 July 1681) was the

He was admitted to the

He was admitted to the

On the enactment of the

On the enactment of the

Plunkett did not object to facing an all-Protestant jury, but the trial soon collapsed as the prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court.

Plunkett did not object to facing an all-Protestant jury, but the trial soon collapsed as the prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court.

Religious and church sites:

*St. Oliver Plunkett Church,

Religious and church sites:

*St. Oliver Plunkett Church,

Mungret, Limerick

* St. Peter's Catholic Church, Drogheda, County Louth *Church of St. Oliver Plunkett, *St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish,

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish,

Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials

digitised by Google Books

St Oliver Plunkett webpage

maintained by Drogheda Borough Council & St. Peter's Church * {{DEFAULTSORT:Plunkett, Oliver 1625 births 1681 deaths 17th-century Irish-language poets 17th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in Ireland 17th-century Roman Catholic martyrs 24 Irish Catholic Martyrs Beatifications by Pope Benedict XV Canonizations by Pope Paul VI Catholic martyrs of England and Wales Executed Irish people Irish Roman Catholic saints Martyred Roman Catholic bishops People associated with the Popish Plot People executed at Tyburn People executed by Stuart England by hanging, drawing and quartering People executed under the Stuarts for treason against England People from County Meath People from Drogheda Poet priests Roman Catholic archbishops of Armagh Victims of the Popish Plot

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Archbishop of Armagh

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

and Primate of All Ireland who was the last victim of the Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate ...

. He was beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their n ...

in 1920 and canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

in 1975, thus becoming the first new Irish saint in almost seven hundred years.

Biography

Oliver Plunkett was born on 1 November 1625 (earlier biographers gave his date of birth as 1 November 1629, but 1625 has been the consensus since the 1930s) inLoughcrew

Loughcrew or Lough Crew () is an area of historical importance near Oldcastle, County Meath, Ireland. It is home to a group of ancient tombs from the 4th millennium BC, some decorated with rare megalithic art, which sit on top of a range of hil ...

, County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, to well-to-do parents with Hiberno-Norman

From the 12th century onwards, a group of Normans invaded and settled in Gaelic Ireland. These settlers later became known as Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans. They originated mainly among Cambro-Norman families in Wales and Anglo-Normans fro ...

ancestors. A grandson of James Plunket, 8th Baron Killeen

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

(died 1595), he was related by birth to a number of landed families, such as the recently ennobled Earls of Roscommon

Earl of Roscommon was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 5 August 1622 for James Dillon, 1st Baron Dillon. He had already been created Baron Dillon on 24 January 1619, also in the Peerage of Ireland. The fourth Earl was a court ...

, as well as the long-established Earls of Fingall, Lords Louth, and Lords Dunsany. Until his sixteenth year, the boy's education was entrusted to his cousin Patrick Plunkett, Abbot of St Mary's, Dublin and brother of Luke Plunkett, the first Earl of Fingall, who later became successively Bishop of Ardagh

The Bishop of Ardagh was a separate episcopal title which took its name after the village of Ardagh, County Longford in the Republic of Ireland. It was used by the Roman Catholic Church until 1756, and intermittently by the Church of Ireland u ...

and of Meath. As an aspirant to the priesthood, he set out for Rome in 1647, under the care of Father Pierfrancesco Scarampi of the Roman Oratory. At this time the Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Confederate Wars, also called the Eleven Years' War (from ga, Cogadh na hAon-déag mBliana), took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in the kin ...

were raging in Ireland; these were essentially conflicts between native Irish Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

s, English and Irish Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia ...

and Nonconformists. Scarampi was the Papal envoy to the Catholic movement known as the Confederation of Ireland. Many of Plunkett's relatives were involved in this organisation.

He was admitted to the

He was admitted to the Irish College in Rome

The Pontifical Irish College is a Roman Catholic seminary for the training and education of priests, in Rome. The College is located at #1, Via dei Santi Quattro, and serves as a residence for clerical students from all over the world. Designated ...

and proved to be an able pupil. He was ordained a priest in 1654, and deputed by the Irish bishops to act as their representative in Rome. Meanwhile, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland w ...

(1649–53) had defeated the Catholic cause in Ireland; in the aftermath, the public practice of Catholicism was banned and Catholic clergy were executed. As a result, it was impossible for Plunkett to return to Ireland for many years. He petitioned to remain in Rome and, in 1657, became a professor of theology. Throughout the period of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

and the first years of Charles II's reign, he successfully pleaded the cause of the Irish Catholic Church, and also served as theological professor at the College of Propaganda Fide. At the Congregation of Propaganda Fide on 9 July 1669 he was appointed Archbishop of Armagh

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

, the Irish primatial see, and was consecrated on 30 November at Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

by the Bishop of Ghent

The Diocese of Ghent (Latin: ''Dioecesis Gandavensis'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Belgium. It is a suffragan in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Mechelen-Brussels ...

, Eugeen-Albert, count d'Allamont. He eventually set foot on Irish soil again on 7 March 1670, as the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

of 1660 had begun on a basis of toleration. The pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropol ...

was granted him in the Consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

* Consistor ...

of 28 July 1670.

After arriving back in Ireland, he tackled drunkenness among the clergy, writing: "Let us remove this defect from an Irish priest, and he will be a saint". The Penal Laws had been relaxed in line with the Declaration of Breda

The Declaration of Breda (dated 4 April 1660) was a proclamation by Charles II of England in which he promised a general pardon for crimes committed during the English Civil War and the Interregnum for all those who recognized Charles as the la ...

in 1660 and he was able to establish a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

College in Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

in 1670. A year later 150 students attended the college, no fewer than 40 of whom were Protestant, making this college the first integrated school in Ireland. His ministry was a successful one and he is said to have confirmed 48,000 Catholics over a 4-year period. The government in Dublin, especially under the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the King ...

, the Duke of Ormonde (the Protestant son of Catholic parents) extended a generous measure of toleration to the Catholic hierarchy until the mid-1670s. Plunkett was executed in Tyburn, England on 1 July 1681. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason and “promoting the Roman faith."

Popish Plot

On the enactment of the

On the enactment of the Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and nonconformists. The underlying principle was that only people taking communion in ...

in 1673, to which Plunkett would not agree for doctrinal reasons, the college was closed and demolished. Plunkett went into hiding, travelling only in disguise, and refused a government edict to register at a seaport to await passage into exile. For the next few years he was largely left in peace since the Dublin government, except when put under pressure from the English government in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, preferred to leave the Catholic bishops alone.

In 1678 the so-called Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate ...

, concocted in England by clergyman Titus Oates

Titus Oates (15 September 1649 – 12/13 July 1705) was an English priest who fabricated the "Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.

Early life

Titus Oates was born at Oakham in Rutland. His father Samuel (1610� ...

, led to further anti-Catholic action. Archbishop Peter Talbot

Peter Talbot (1620 – November 1680) was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin from 1669 to his death in prison. He was a victim of the Popish Plot.

Early life

Talbot was born at Malahide, County Dublin, Ireland, in 1620. He was the second ...

of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

was arrested, and Plunkett again went into hiding. The Privy Council of England

The Privy Council of England, also known as His (or Her) Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (), was a body of advisers to the sovereign of the Kingdom of England. Its members were often senior members of the House of Lords and the House of ...

, in Westminster, was told that Plunkett had plotted a French invasion. The moving spirit behind the campaign is said to have been Arthur Capell, the first Earl of Essex, who had been Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1672-77 and hoped to resume the office by discrediting the Duke of Ormonde. However Essex was not normally a ruthless or unprincipled man, and his later plea for mercy suggests that he had never intended that Plunkett should actually die.

Trial

Despite being on the run and with a price on his head, Plunkett refused to leave his flock. At some point before his finalincarceration

Imprisonment is the restraint of a person's liberty, for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is " false imprisonment". Imprisonment does not necessar ...

, he took refuge in a church that once stood in the townland of Killartry, in the parish of Clogherhead

Clogherhead () is a fishing village in County Louth, Ireland. Located in a natural bay on the east coast it is bordered by the villages of Annagassan to the north and Termonfeckin to the south. It has a population of 2,145 according to the 2 ...

in County Louth

County Louth ( ; ga, An Lú) is a coastal Counties of Ireland, county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Louth is bordered by the counties of County Meath, M ...

, seven miles outside Drogheda. He was arrested in Dublin on 6 December 1679 and imprisoned in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the s ...

, where he gave absolution to the dying Talbot. Plunkett was tried at Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

for conspiring against the state by allegedly plotting to bring 20,000 French soldiers into the country, and for levying a tax on his clergy to support 70,000 men for rebellion. Though this was unproven, some in government circles were worried about the possibility that a repetition of the Irish rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantat ...

was being planned and in any case, this was a convenient excuse for proceeding against Plunkett. The Duke of Ormonde, aware that Lord Essex was using the crisis to undermine him, did not defend Plunkett in public. In private however, he made clear his belief in Plunkett's innocence and his contempt for the informers against him: "silly drunken vagabonds... whom no schoolboy would trust to rob an orchard".

Plunkett did not object to facing an all-Protestant jury, but the trial soon collapsed as the prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court.

Plunkett did not object to facing an all-Protestant jury, but the trial soon collapsed as the prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court. Lord Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

knew Plunkett would never be convicted in Ireland, irrespective of the jury's composition, and so had Plunkett moved to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

in London in order to face trial at Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

. The first grand jury found no true bill, but he was not released. The second trial has generally been regarded as a serious miscarriage of justice; Plunkett was denied defending counsel (although Hugh Reily

Hugh Reily, also known as Hugh Reilly or Hugh O'Reilly (c.1630 – 1695) was M.P. for Cavan Borough in the Patriot Parliament of 1689 and a famous political author. His Irish name was Aodh O'Raghallaigh and his ancestors were the Lords of East ...

acted as his legal advisor) and time to assemble his defence witnesses, and he was also frustrated in his attempts to obtain the criminal records of those who were to give evidence against him. His servant James McKenna, and a relative, John Plunkett, had travelled back to Ireland and failed within the time available to bring back witnesses and evidence for the defence. During the trial, Archbishop Plunkett had disputed the right of the court to try him in England and he also drew attention to the criminal past of the witnesses, but to no avail. Lord Chief Justice

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

Sir Francis Pemberton addressing these complaints said to Plunkett: "Look you, Mr. Plunket, it is in vain for you to talk and make this discourse here now..." and later on again: "Look you, Mr. Plunket, don't mis-spend your own time; for the more you trifle in these things, the less time you will have for your defence".

The Scottish clergyman and future Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset. The see is in the City of Salisbury where the bishop's seat ...

, Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet (18 September 1643 – 17 March 1715) was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was highly respected as a cleric, a preacher, an academi ...

, an eyewitness to the Plot trials, had no doubt of the innocence of Plunkett, whom he praised as a wise and sober man who wished only to live peacefully and tend to his congregation. Writing in the 19th century, Lord Campbell said of the judge, Pemberton, that the trial was a disgrace to himself and his country. More recently the High Court judge Sir James Comyn called it a grave mistake: while Plunkett, by virtue of his office, was clearly guilty of "promoting the Catholic faith", and may possibly have had some dealings with the French, there was never the slightest evidence that he had conspired against the King's life.

Execution

Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

Plunkett was found guilty of high treason in June 1681 "for promoting the Roman faith", and was condemned to death. In passing judgement, the Chief Justice said: "You have done as much as you could to dishonour God in this case; for the bottom of your treason was your setting up your false religion, than which there is not any thing more displeasing to God, or more pernicious to mankind in the world". The jury returned within fifteen minutes with a guilty verdict and Archbishop Plunkett replied: "''Deo Gratias''" (Latin for "Thanks be to God").

Numerous pleas for mercy were made but Charles II, although himself a reputed crypto-Catholic, thought it too politically dangerous to spare Plunkett. The French ambassador to England, Paul Barillon Paul Barillon d'Amoncourt, the marquis de Branges (1630–1691), was the French ambassador to England from 1677 to 1688. His dispatches from England to Louis XIV have been very useful to historians of the period, though an expected bias may be prese ...

, conveyed a plea for mercy from his king, Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

. Charles told him frankly that he knew Plunkett to be innocent, but that the time was not right to take so bold a step as to pardon him. Lord Essex, apparently realising too late that his intrigues had led to the condemnation of an innocent man, made a similar plea for mercy. The King, normally the most self-controlled of men, turned on Essex in fury, saying: "his blood be on your head – you could have saved him but would not, I would save him and dare not".

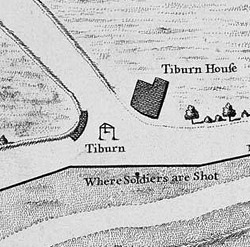

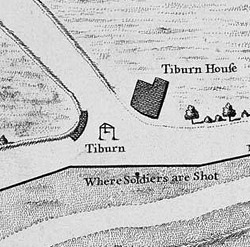

Plunkett was hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and sout ...

on 1 July 1681 (11 July NS), aged 55, the last Catholic martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

to die in England. His body was initially buried in two tin boxes, next to five Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

who had died previously, in the courtyard of St Giles in the Fields church. The remains were exhumed in 1683 and moved to the Benedictine monastery at Lamspringe

Lamspringe is a village and a municipality in the Hildesheim (district), district of Hildesheim, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated approximately 20 km south of Hildesheim. Since 1 November 2016, the former municipalities Harbarnsen, Ne ...

, near Hildesheim

Hildesheim (; nds, Hilmessen, Hilmssen; la, Hildesia) is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany with 101,693 inhabitants. It is in the district of Hildesheim, about southeast of Hanover on the banks of the Innerste River, a small tributary of the ...

in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. The head was brought to Rome, and from there to Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the ...

, and eventually to Drogheda where since 29 June 1921 it has rested in Saint Peter's Church. Most of the body was brought to Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey is a Benedictine monastery in England and the senior community of the English Benedictine Congregation. Until 2019, the community had close links with Downside School, for the education of children aged eleven to eighteen. Both ...

, England, where the major part is located today, with some parts remaining at Lamspringe. On the occasion of his canonization in 1975 his casket was opened and some parts of his body were given to St Peter's Church in Drogheda Ireland.

Legacy

Oliver Plunkett was beatified in 1920 and canonized in 1975, the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years, and the first of theIrish martyrs

Irish Catholic Martyrs () were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for dying for their Catholic faith between 1537 and 1681 in Ireland. The canonisation of Oliver Plunkett in 1975 brought an awareness of the others who d ...

to be beatified. For the canonisation, the customary second miracle was waived. He has since been followed by 17 other Irish martyrs who were beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their n ...

by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

in 1992. Among them were Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley

Dermot O'Hurley (c. 1530 – 19 or 20 June 1584)—also ''Dermod or Dermond O'Hurley'': ga, Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile—was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Cashel in Ireland during the reign of Elizabeth I, who was put to death for treason. He ...

, Margaret Ball, and the Wexford Martyrs.

In 1920 a mosaic of him at Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral is the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales. It is the largest Catholic church in the UK and the seat of the Archbishop of Westminster.

The site on which the cathedral stands in the City o ...

, London, was created by Boris Anrep

Boris Vasilyevich Anrep (russian: Борис Васильевич Анреп; 27 September 1883 – 7 June 1969) was a Russian artist, active in Britain, who devoted himself to the art of mosaic. In Britain, he is known for his monumental mosai ...

.

As a spectacle alone, a rally and Mass for St Oliver Plunkett on London's Clapham Common

Clapham Common is a large triangular urban park in Clapham, south London, England. Originally common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, it was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878. It is of g ...

was a remarkable triumph. The Common was virtually taken over for a celebration of the 300th anniversary of Plunkett's martyrdom. Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich

Tomás Séamus Cardinal Ó Fiaich KGCHS (3 November 1923 – 8 May 1990) was an Irish prelate of the Catholic Church. He served as the Catholic Primate of All Ireland and Archbishop of Armagh from 1977 until his death. He was created a Cardinal ...

, twenty enrobed bishops and a number of abbots mounted a stage beneath a scaffolding shelter on 1 July 1981. Ó Fiaich had flown there in a helicopter with Plunkett's head. The occasion attracted thousands of pilgrims to the park.

In 1997 Plunkett was made a patron saint for peace and reconciliation in Ireland, adopted by the prayer group campaigning for peace in Ireland, "St. Oliver Plunkett for Peace and Reconciliation".

Dedications to Oliver Plunkett

Religious and church sites:

*St. Oliver Plunkett Church,

Religious and church sites:

*St. Oliver Plunkett Church, Diocese of Down and Connor

The Diocese of Down and Connor, ( ga, Deoise an Dúin agus Chonaire) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Northern Ireland. It is one of eight suffragan dioceses in the ecclesiastical province of the me ...

, County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett ChurchMungret, Limerick

* St. Peter's Catholic Church, Drogheda, County Louth *Church of St. Oliver Plunkett,

Blackrock, County Louth

Blackrock () is a seaside village just to the south of Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland. The small town is in the townland of Haggardstown and part of the Dundalk metropolitan area. The population of the village is between 3,000 and 5,000.

Hist ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Church, Clonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Drogheda and Wexford. With the exception of the townla ...

, County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early 13th century, shortly after ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett Church, Renmore

Renmore () is a suburb of Galway City, Ireland, situated approximately 2 km to the east of the city. Renmore runs east along the coast and south of Dublin Road, from the shore of Lough Atalia on its west side to Lurgan Park on its east. The ...

, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

*Shrine at Loughcrew, County Meath

*Downside Abbey, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett Catholic Church, Snellville, Georgia

Snellville is a city in Gwinnett County, Georgia, Gwinnett County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States, east of Atlanta. The population was 18,242 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, and in 2019 the estimated population was 2 ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett Catholic Church, Strathfoyle, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland Diocese of Derry

*St. Oliver Plunkett Parish (Consolidated), Fredericktown, Pennsylvania

Fredericktown is a census-designated place located in East Bethlehem Township, Washington County in the state of Pennsylvania. The community was part of the Fredericktown-Millsboro CDP for the 2000 census, but was split into two separate CDPs ...

*St. Oliver's Cemetery, Cork City

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city's ...

, County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns a ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish, Cannon Hill, Queensland

Cannon Hill is a suburb in the City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. In the , Cannon Hill had a population of 5,533 people.

Geography

The suburb is located by road east of the Brisbane GPO.

History

Cannon Hill was originally inhabited by ...

Australia

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish, Harris Park, New South Wales

Harris Park is a suburb of Greater Western Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Harris Park is located 19 kilometres west of the Sydney central business district in the local government area of the City of Parramatta and is part o ...

, Australia

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish,

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Parish, Pascoe Vale, Victoria

Pascoe Vale is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, north of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Merri-bek local government area. Pascoe Vale recorded a population of 18,171 at the 2021 census.

History

P ...

, Australia

*The Church of Our Lady St Mary of Glastonbury

The Church of Our Lady St Mary of Glastonbury in Glastonbury, Somerset, England, is a Roman Catholic church that was completed in 1940.

History

The church sits along Magdalene Street facing the medieval Abbot's Kitchen across the road in Glast ...

, Somerset, England, contains relics from Oliver Plunkett in all of its reliquaries.

Schools:

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Post Primary School, Oldcastle, County Meath

Oldcastle () is a town in County Meath, Ireland. It is located in the north-west of the county near the border with Cavan, approximately 13 miles (21 km) from Kells. The R154 and R195 regional roads cross in the town's market square.

A ...

*Scoil Oilibhéir SN, Baile Átha Cliath 15

*St. Oliver Plunkett's National School, Clonmel, County Tipperary

*St. Oliver Plunkett Primary School, Beragh

Beragh (from Irish: ''Bearach'', meaning "place of points/hills/standing stones") is a village and townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is about southeast of Omagh and is in the Fermanagh and Omagh District Council area. The 20 ...

, County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an administrative division for local government but retai ...

*St. Oliver Plunket National School, Blackrock, County Louth

*St. Oliver Plunket National School, Newcastle, Athenry

Athenry (; ) is a town in County Galway, Ireland, which lies east of Galway city. Some of the attractions of the medieval town are its town wall, Athenry Castle, its priory and its 13th century street-plan. The town is also well known by virt ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett School, Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

, County Antrim

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Primary School, Forkhill, County Armagh

County Armagh (, named after its county town, Armagh) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the southern shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of an ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Primary School, Kilmore, County Armagh

*St. Oliver Plunkett School, Malahide

Malahide ( ; ) is an affluent coastal settlement in Fingal, County Dublin, Ireland, situated north of Dublin city. It has a village centre surrounded by suburban housing estates, with a population of over 17,000.

Malahide Castle dates from th ...

, County Dublin

*Blessed Oliver Plunkett Boys' National School, Moate

Moate (; ) is a town in County Westmeath, Ireland.

The name ''An Móta'' is derived from the term motte-and-bailey, as the Normans built an example of this type of fortification here. The earthwork is still visible behind the buildings on the m ...

, County Westmeath

"Noble above nobility"

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Westmeath.svg

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 =

, subdivis ...

*St. Oliver Plunkett National School, Navan

Navan ( ; , meaning "the Cave") is the county town of County Meath, Ireland. In 2016, it had a population of 30,173, making it the tenth largest settlement in Ireland. It is at the confluence of the River Boyne and Blackwater, around 50&nb ...

, County Meath

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Primary School, Newtownhamilton

Newtownhamilton is a small town and civil parish in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It lies predominantly within Tullyvallan townland. The civil parish is within the historic barony of Fews Upper. In the 2011 Census it had 2,836 inhabitants ...

, County Armagh

* Downside School, Somerset

*Oliver Plunkett's Primary School, Strathfoyle

Strathfoyle (from ga, Srath Feabhail) is a village in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland It is about north east of Derry. It was newly built in different phases between the late 1950s and the early 1960s, with many new recent additions to th ...

, County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. ...

*Mayfield College

Mayfield College is a defunct Roman Catholic boys' boarding school founded as thin 1865–1866 by the American-born Dowager Duchess of Leeds one mile from Mayfield, East Sussex. The main building and attached chapel were built in the Gothic sty ...

, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

*St. Oliver's Primary School, Harris Park, New South Wales, Australia

*St. Oliver Plunkett Primary School, Cannon Hill, Queensland, Australia

*St. Oliver Plunkett Primary School, Pascoe Vale, Victoria, Australia

*St. Oliver Plunkett NS, Monkstown, Co. Dublin

*St. Oliver Plunkett NS, Killina, Co. Kildare

County Kildare ( ga, Contae Chill Dara) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the county ...

Sports:

* St. Oliver Plunkett Park, Crossmaglen

Crossmaglen (, ) is a village and townland in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It had a population of 1,610 in the 2011 Census and is the largest village in South Armagh. The village centre is the site of a large Police Service of Northern Ire ...

, County Armagh

* St. Oliver Plunkett Park, Emyvale, Co. Monaghan

*Oliver Plunketts GAA, Drogheda, County Louth.

*Oliver Plunketts GAA

St. Oliver Plunkett's is a Gaelic Athletic Association club in Cork, Ireland. The club is based in Ahiohill. It fields teams in hurling and Gaelic football competitions organized by Cork GAA and the Carbery divisional board.

History

The clu ...

, Ahiohill, County Cork

*St Oliver Plunketts/Eoghan Ruadh GAA

St Oliver Plunkett/Eoghan Ruadh (Irish: ''Naomh Oilibhéar Pluincéad, Eoghan Ruadh'' ) is a Gaelic Athletic Association club situated on the Navan Road on the northside of Dublin, Ireland. St Oliver Plunkett Eoghan Ruadh senior football team a ...

, Dublin, County Dublin

*Greenlough GAC

Saint Oliver Plunkett's GAC Greenlough ( ga, CLG Naomh Oilibheir Pluinceid Grainlocha) is a Gaelic Athletic Association club based in Clady/ Greenlough, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The club is a member of Derry GAA and currently cate ...

, Clady, County Londonderry

*Oliver Plunkett Cup of the Cavan Senior Football Championship

The Cavan Senior Football Championship is an annual Gaelic Athletic Association club competition between the top Cavan Gaelic football clubs. It was first competed for in 1888. The winners get the Oliver Plunkett Cup and qualifies to represent t ...

*St Oliver's Boys, Clonmel, County Tipperary (defunct, now known as Clonmel Celtic FC)

Other:

* Oliver Plunkett Street, Cork City, County Cork

*St. Oliver Plunkett Road, Letterkenny, County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrcon ...

*St Oliver Plunkett Rd. Ballymore Eustace. Co.Kildare

*St. Oliver Plunkett's Bridge, County Offaly

County Offaly (; ga, Contae Uíbh Fhailí) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is named after the Ancient Ireland ...

*Oliver Plunkett Street, Mullingar

Mullingar ( ; ) is the county town of County Westmeath in Ireland. It is the third most populous town in the Midland Region, with a population of 20,928 in the 2016 census.

The Counties of Meath and Westmeath Act 1543 proclaimed Westmeath ...

, County Westmeath

*St. Oliver Plunkett's GAA, Drogheda, Co. Louth

*Oliver Plunkett Road, Monkstown, County Dublin

*Oliver Plunkett Avenue, Monkstown, County Dublin

* St Oliver's GAA, Waterford

An Aer Lingus plane is named for him

. Plunkett Avenue, Mervue, Galway city.

In popular culture

* InHarold Pinter

Harold Pinter (; 10 October 1930 – 24 December 2008) was a British playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. A Nobel Prize winner, Pinter was one of the most influential modern British dramatists with a writing career that span ...

's '' The Birthday Party'', McCann asks Stanley "What about the blessed Oliver Plunkett?"

* In J. P. Donleavy's ''The Ginger Man

''The Ginger Man'' is a novel, first published in Paris in 1955, by J. P. Donleavy. The story is set in Dublin, Ireland, in post-war 1947. Upon its publication, it was banned both in Ireland and the United States of America by reason of obsce ...

'', Sebastian Dangerfield repeatedly calls on the name of "the Blessed Oliver" and, towards the end of the book, receives a wooden carving of the saint's head.

* In David Caffrey

David Caffrey is an Irish film director. His most recent film is ''Grand Theft Parsons'' starring Johnny Knoxville and Christina Applegate. The film is an account of an urban myth about the death of country rock legend, Gram Parsons.

Filmography ...

's 2001 film '' On the Nose'', Nana, played by Francis Burke refers to an Aboriginal person's head in a large specimen jar as "Oliver Plunkett".

* In Colin Bateman

Colin Bateman (known mononymously as Bateman) is a novelist, screenwriter and former journalist from Bangor, County Down, Northern Ireland.

Biography

Born on 13 June 1962, Bateman attended Bangor Grammar School leaving at 16 when he was hired ...

's 2004 novel, '' Bring Me the Head of Oliver Plunkett'', the head of Oliver Plunkett is stolen from St. Peter's Church.

* Too Much Joy

Too Much Joy is an American alternative rock music group, that formed in the early 1980s in Scarsdale, New York.

Members

The original members were Tim Quirk (vocals), Jay Blumenfield (guitar, vocals), Sandy Smallens (bass, vocals) and Tommy Vi ...

's 2021 album ''Mistakes Were Made'' includes a song called "Oliver Plunkett's Head".

Timeline

*4 March 1651 –tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice i ...

& minor orders

Minor orders are ranks of church ministry. In the Catholic Church, the predominating Latin Church formerly distinguished between the major orders —priest (including bishop), deacon and subdeacon—and four minor orders—acolyte, exorcist, lec ...

*20 December 1653 – ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

as subdeacon

Subdeacon (or sub-deacon) is a minor order or ministry for men in various branches of Christianity. The subdeacon has a specific liturgical role and is placed between the acolyte (or reader) and the deacon in the order of precedence.

Subdeacons i ...

*26 December 1653 – ordained as deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

*1 January 1654 – ordained as priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

in Rome

*November 1657 – appointed Professor of Theology at Propaganda college, Rome

*1 December 1669 – consecrated

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different gro ...

as archbishop

*7 March 1670 – landed at Ringsend, Dublin, ending 23 years of self-imposed exile abroad

*6 December 1679 – arrested

*23 July 1680 – trial

*24 October 1680 – transfer from Ireland to London

*8 June 1681 – trial

*15 June 1681 – sentenced to death

*1 July 1681 ( OS) = 11 July 1681 (NS) – hanged, drawn, quartered (the punishment for treason against the state), beheaded

*9 December 1886 declared venerable

The Venerable (''venerabilis'' in Latin) is a style, a title, or an epithet which is used in some Western Christian churches, or it is a translation of similar terms for clerics in Eastern Orthodoxy and monastics in Buddhism.

Christianity

Cat ...

*17 March 1918 – declaration of martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

*Pentecost Sunday

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers o ...

, 23 May 1920 – beatified

*12 October 1975 – canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

References

Works cited

*''Blessed Oliver Plunkett: Historical Studies'', Gill, Dublin, 1937. * * * * * *External links

Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials

digitised by Google Books

St Oliver Plunkett webpage

maintained by Drogheda Borough Council & St. Peter's Church * {{DEFAULTSORT:Plunkett, Oliver 1625 births 1681 deaths 17th-century Irish-language poets 17th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in Ireland 17th-century Roman Catholic martyrs 24 Irish Catholic Martyrs Beatifications by Pope Benedict XV Canonizations by Pope Paul VI Catholic martyrs of England and Wales Executed Irish people Irish Roman Catholic saints Martyred Roman Catholic bishops People associated with the Popish Plot People executed at Tyburn People executed by Stuart England by hanging, drawing and quartering People executed under the Stuarts for treason against England People from County Meath People from Drogheda Poet priests Roman Catholic archbishops of Armagh Victims of the Popish Plot