Sporadic permafrost on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the

Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

In contrast to the relative dearth of reports on frozen ground in North America prior to World War II, a vast literature on basic permafrost science and the engineering aspects of permafrost was available in Russian. Some Russian authors relate permafrost research with the name

In contrast to the relative dearth of reports on frozen ground in North America prior to World War II, a vast literature on basic permafrost science and the engineering aspects of permafrost was available in Russian. Some Russian authors relate permafrost research with the name

Permafrost is

Permafrost is

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice, aufeis (stranded river ice) and—probably the most prevalent—buried glacial ice.

Intrasedimental ice forms by in-place freezing of subterranean waters and is dominated by segregational ice which results from the crystallizational differentiation taking place during the freezing of wet sediments, accompanied by water migrating to the freezing front.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada and also includes intrusive and injection ice.

Arctic permafrost has been diminishing for decades. Globally, permafrost warmed by about between 2007 and 2016, with stronger warming observed in the continuous permafrost zone relative to the discontinuous zone. The consequence is thawing soil, which may be weaker, and release of methane, which contributes to an increased rate of global warming as part of a climate change feedback, feedback loop caused by microbial decomposition. Wetlands drying out from drainage or evaporation compromises the ability of plants and animals to survive. When permafrost continues to diminish, many climate change scenarios will be amplified. In areas where permafrost is high, nearby human infrastructure may be damaged severely by the thawing of permafrost. It is believed that Permafrost carbon cycle, carbon storage in permafrost globally is approximately 1600 gigatons; equivalent to twice the atmospheric pool.

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice, aufeis (stranded river ice) and—probably the most prevalent—buried glacial ice.

Intrasedimental ice forms by in-place freezing of subterranean waters and is dominated by segregational ice which results from the crystallizational differentiation taking place during the freezing of wet sediments, accompanied by water migrating to the freezing front.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada and also includes intrusive and injection ice.

Arctic permafrost has been diminishing for decades. Globally, permafrost warmed by about between 2007 and 2016, with stronger warming observed in the continuous permafrost zone relative to the discontinuous zone. The consequence is thawing soil, which may be weaker, and release of methane, which contributes to an increased rate of global warming as part of a climate change feedback, feedback loop caused by microbial decomposition. Wetlands drying out from drainage or evaporation compromises the ability of plants and animals to survive. When permafrost continues to diminish, many climate change scenarios will be amplified. In areas where permafrost is high, nearby human infrastructure may be damaged severely by the thawing of permafrost. It is believed that Permafrost carbon cycle, carbon storage in permafrost globally is approximately 1600 gigatons; equivalent to twice the atmospheric pool.

At the Last Glacial Maximum, continuous permafrost covered a much greater area than it does today, covering all of ice-free Europe south to about Szeged (southeastern Hungary) and the Sea of Azov (then dry land) and East Asia south to present-day Changchun and Abashiri, Hokkaidō, Abashiri. In North America, only an extremely narrow belt of permafrost existed south of the ice sheet at about the latitude of New Jersey through southern Iowa and northern Missouri, but permafrost was more extensive in the drier western regions where it extended to the southern border of Idaho and Oregon. In the southern hemisphere, there is some evidence for former permafrost from this period in central Otago and Argentina, Argentine Patagonia, but was probably discontinuous, and is related to the tundra. Alpine permafrost also occurred in the Drakensberg during glacial maxima above about .

At the Last Glacial Maximum, continuous permafrost covered a much greater area than it does today, covering all of ice-free Europe south to about Szeged (southeastern Hungary) and the Sea of Azov (then dry land) and East Asia south to present-day Changchun and Abashiri, Hokkaidō, Abashiri. In North America, only an extremely narrow belt of permafrost existed south of the ice sheet at about the latitude of New Jersey through southern Iowa and northern Missouri, but permafrost was more extensive in the drier western regions where it extended to the southern border of Idaho and Oregon. In the southern hemisphere, there is some evidence for former permafrost from this period in central Otago and Argentina, Argentine Patagonia, but was probably discontinuous, and is related to the tundra. Alpine permafrost also occurred in the Drakensberg during glacial maxima above about .

File:Permafrost in Herschel Island 001.jpg, Thawing permafrost in Herschel Island, Canada, 2013

File:Permafrost in Herschel Island 015.jpg, Permafrost and ice in Herschel Island, Canada, 2012

File:Permafrost thaw ponds in Hudson Bay Canada near Greenland.jpg, Permafrost thaw ponds on peatland in Hudson Bay, Canada in 2008.

File:Phoenix_Sol_0_horizon.jpg, Permafrost polygons on Mars imaged by the Phoenix (spacecraft), Phoenix lander.

File:PSP 008301 2480 cut a.jpg , False-color Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter image of polygonal surface pattern.

File:Patterned_ground_devon_island.jpg , Patterned ground on earth.

File:PICT4417Sykhus.JPG, Modern buildings in permafrost zones may be built on piles to avoid permafrost-thaw foundation failure from the heat of the building.

File:Trans-Alaska Pipeline (1).jpg, Heat pipe#Permafrost cooling, Heat pipes in vertical supports maintain a frozen bulb around portions of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline that are at risk of thawing.

File:Yakoutsk Construction d'immeuble.jpg, Pile foundations in Yakutsk, a city underlain with continuous permafrost.

File:Raised pipes in permafrost.jpg, District heating pipes run above ground in Yakutsk to avoid thawing permafrost.

Pleistocene & Permafrost Foundation

Permafrostwatch

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Infographics about permafrostInternational Permafrost Association (IPA)

Center for PermafrostPermafrost – what is it? – YouTube

(Alfred Wegener Institute) {{Authority control Permafrost, Geography of the Arctic Geomorphology Montane ecology Patterned grounds Pedology Periglacial landforms 1940s neologisms Cryosphere

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface is underlain by permafrost, with the total area of around 18 million km2. This includes substantial areas of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

, Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

. It can also be located on mountaintops in the Southern Hemisphere and beneath ice-free areas in the Antarctic.

Permafrost does not have to be the first layer that is on the ground. It can be from an inch to several miles deep under the Earth's surface. It frequently occurs in ground ice, but it can also be present in non-porous bedrock. Permafrost is formed from ice holding various types of soil, sand, and rock in combination.

Permafrost contains large amounts of biomass and decomposed biomass that has been stored as methane and carbon dioxide, making tundra soil a carbon sink

A carbon sink is anything, natural or otherwise, that accumulates and stores some carbon-containing chemical compound for an indefinite period and thereby removes carbon dioxide () from the atmosphere.

Globally, the two most important carbon si ...

. As global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

heats the ecosystem and causes soil thawing, the permafrost carbon cycle

The permafrost carbon cycle or Arctic carbon cycle is a sub-cycle of the larger global carbon cycle. Permafrost is defined as subsurface material that remains below 0o C (32o F) for at least two consecutive years. Because permafrost soils remain f ...

accelerates and releases much of these soil-contained greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, creating a feedback cycle that increases climate change. Thawing of permafrost is one of the effects of climate change

The effects of climate change impact the physical environment, ecosystems and human societies. The environmental effects of climate change are broad and far-reaching. They affect the water cycle, oceans, sea and land ice ( glaciers), sea le ...

. While emissions from thawing permafrost will be significant enough to lead to additional warming, they will likely not be enough to trigger a self-reinforcing feedback leading to "runaway warming".Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

Study of permafrost

In contrast to the relative dearth of reports on frozen ground in North America prior to World War II, a vast literature on basic permafrost science and the engineering aspects of permafrost was available in Russian. Some Russian authors relate permafrost research with the name

In contrast to the relative dearth of reports on frozen ground in North America prior to World War II, a vast literature on basic permafrost science and the engineering aspects of permafrost was available in Russian. Some Russian authors relate permafrost research with the name Alexander von Middendorff

Alexander Theodor von Middendorff (russian: Алекса́ндр Фёдорович Ми́ддендорф; tr. ; 18 August 1815 – 24 January 1894) was a zoologist and explorer of Baltic German and Estonian extraction. He is known for his ex ...

(1815–1894). However, Russian scientists also realized, that Karl Ernst von Baer

Karl Ernst Ritter von Baer Edler von Huthorn ( – ) was a Baltic German scientist and explorer. Baer was a naturalist, biologist, geologist, meteorologist, geographer, and is considered a, or the, founding father of embryology. He was ...

must be given the attribute "founder of scientific permafrost research". In 1843, Baer's original study “materials for the study of the perennial ground-ice” was ready to be printed. Baer's detailed study consists of 218 pages and was written in German language, as he was a Baltic German scientist. He was teaching at the University of Königsberg

The University of Königsberg (german: Albertus-Universität Königsberg) was the university of Königsberg in East Prussia. It was founded in 1544 as the world's second Protestant academy (after the University of Marburg) by Duke Albert of Pruss ...

and became a member of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. This world's first permafrost textbook was conceived as a complete work and ready for printing in 1843. But it remained lost for around 150 years. However, from 1838 onwards, Baer published several individual publications on permafrost. The Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across ...

honoured Baer with the publication of a tentative Russian translation of his study in 1942.

These facts were completely forgotten after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Thus in 2001 the discovery of the typescript from 1843 in the library archive

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or ...

s of the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von ...

and its annotated publication was a scientific sensation. The full text of Baer's original work is available online (234 pages). The editor added to the facsimile reprint a preface in English, two colour permafrost maps of Eurasia and some figures of permafrost features. Baer's text is introduced with detailed comments and references on additional 66 pages written by the Estonian historian Erki Tammiksaar. The work is notable because Baer's observations on permafrost distribution and periglacial morphological descriptions are seen as largely correct to the present day. With his compilation and analysis of all available data on ground ice and permafrost, Baer laid the foundation for the modern permafrost terminology. Baer's southern limit of permafrost in Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago ...

drawn in 1843 corresponds well with the actual southern limit on the ''Circum-Arctic Map of Permafrost and Ground Ice Conditions'' of the International Permafrost Association

The International Permafrost Association (IPA), founded in 1983, has as its objectives to foster the dissemination of knowledge concerning permafrost and to promote cooperation among persons and national or international organisations engaged in ...

(edited by J. Brown et al.).

Beginning in 1942, Siemon William Muller

Siemon William Muller (May 9, 1900 – September 9, 1970) was an American paleontologist and geologist, known for his studies on Triassic paleontology and stratigraphy, and for his work on permafrost.

Siemon Muller was born in Blagoveshchensk o ...

delved into the relevant Russian literature held by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

and the U.S. Geological Survey Library so that he was able to furnish the government an engineering field guide and a technical report about permafrost by 1943", the year in which he coined the term as a contraction of permanently frozen ground. Although originally classified (as U.S. Army. Office of the Chief of Engineers, ''Strategic Engineering Study'', no. 62, 1943), in 1947 a revised report was released publicly, which is regarded as the first North American treatise on the subject.

Classification and extent

Permafrost is

Permafrost is soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt

Dirt is an unclean matter, especially when in contact with a person's clothes, skin, or possessions. In such cases, they are said to become dirty.

Common types of dirt include:

* Debri ...

, rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

or sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

that is frozen for more than two consecutive years. In areas not covered by ice, it exists beneath a layer of soil, rock or sediment, which freezes and thaws annually and is called the "active layer". In practice, this means that permafrost occurs at an mean annual temperature of or below. Active layer thickness varies with the season, but is 0.3 to 4 meters thick (shallow along the Arctic coast; deep in southern Siberia and the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau).

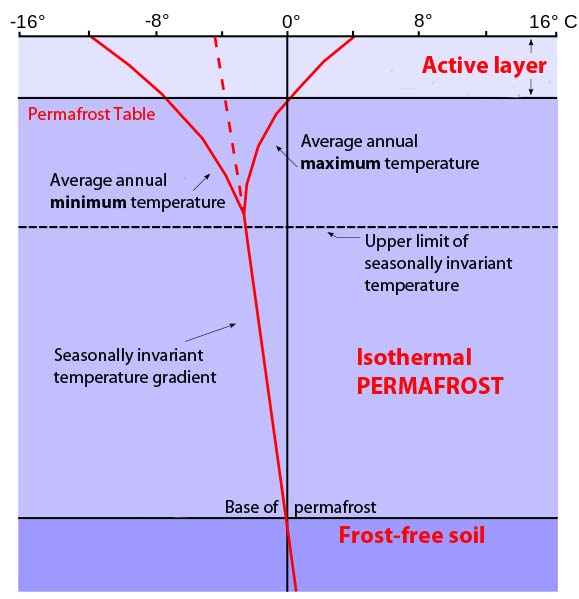

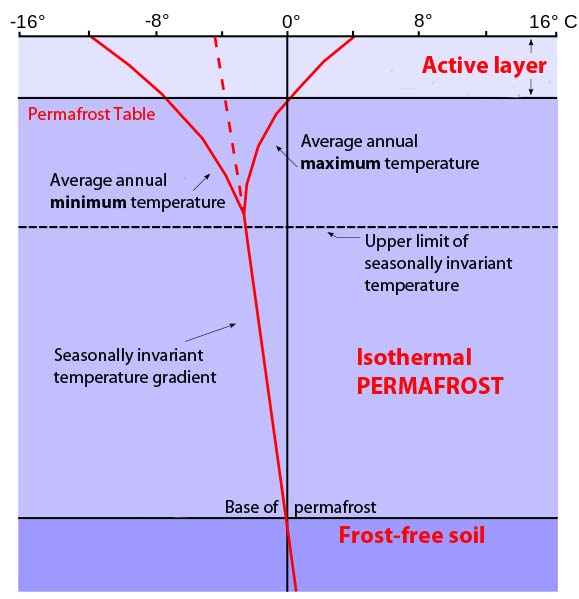

The extent of permafrost is displayed in terms of permafrost zones, which are defined according to the area underlain by permafrost as continuous (90%–100%), discontinuous (50%–90%), sporadic (10%–50%), and isolated patches (10% or less). These permafrost zones cover together approximately 22% of the Northern Hemisphere. Continuous permafrost zone covers slightly more than half of this area, discontinuous permafrost around 20 percent, and sporadic permafrost together with isolated patches little less than 30 percent. Because permafrost zones are not entirely underlain by permafrost, only 15% of the ice-free area of the Northern Hemisphere is actually underlain by permafrost. Most of this area is found in Siberia, northern Canada, Alaska and Greenland. Beneath the active layer annual temperature swings of permafrost become smaller with depth. The deepest depth of permafrost occurs where geothermal heat maintains a temperature above freezing. Above that bottom limit there may be permafrost with a consistent annual temperature—"isothermal permafrost".

Continuity of coverage

Permafrost typically forms in anyclimate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologi ...

where the mean annual air temperature is lower than the freezing point of water

Water (chemical formula ) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living ...

. Exceptions are found in humid boreal forests, such as in Northern Scandinavia and the North-Eastern part of European Russia west of the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

, where snow acts as an insulating blanket. Glaciated areas may also be exceptions. Since all glaciers are warmed at their base by geothermal heat, temperate glaciers, which are near the pressure-melting point throughout, may have liquid water at the interface with the ground and are therefore free of underlying permafrost. "Fossil" cold anomalies in the Geothermal gradient

Geothermal gradient is the rate of temperature change with respect to increasing depth in Earth's interior. As a general rule, the crust temperature rises with depth due to the heat flow from the much hotter mantle; away from tectonic plate bo ...

in areas where deep permafrost developed during the Pleistocene persist down to several hundred metres. This is evident from temperature measurements in boreholes in North America and Europe.

Discontinuous permafrost

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth as a result of the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered—usually with a northern or southernaspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

(in north and south hemispheres respectively) —creating ''discontinuous permafrost''. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not be even discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into ''extensive discontinuous permafrost'', where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and ''sporadic permafrost'', where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in ''un-glaciated'' Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

and Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

where the present depth of permafrost is a relic of climatic conditions during glacial ages where winters were up to colder than those of today.

Continuous permafrost

At mean annual soil surface temperatures below the influence of aspect can never be sufficient to thaw permafrost and a zone of ''continuous permafrost'' (abbreviated to CPZ) forms. A ''line of continuous permafrost'' in the Northern Hemisphere represents the most southern border where land is covered by continuous permafrost or glacial ice. The line of continuous permafrost varies around the world northward or southward due to regional climatic changes. In the southern hemisphere, most of the equivalent line would fall within theSouthern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

if there were land there. Most of the Antarctic continent

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

is overlain by glaciers, under which much of the terrain is subject to basal melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

. The exposed land of Antarctica is substantially underlain with permafrost, some of which is subject to warming and thawing along the coastline.

Alpine permafrost

Alpine permafrost occurs at elevations with low enough average temperatures to sustain perennially frozen ground; much alpine permafrost is discontinuous. Estimates of the total area of alpine permafrost vary. Bockheim and Munroe combined three sources and made the tabulated estimates by region, totaling . Alpine permafrost in theAndes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

has not been mapped. Its extent has been modeled to assess the amount of water bound up in these areas. In 2009, a researcher from Alaska found permafrost at the level on Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro, approximately 3° south of the equator.

Subsea permafrost

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the seabed and exists in the continental shelves of the polar regions. These areas formed during the last ice age, when a larger portion of Earth's water was bound up in ice sheets on land and when sea levels were low. As the ice sheets melted to again become seawater, the permafrost became submerged shelves under relatively warm and salty boundary conditions, compared to surface permafrost. Therefore, subsea permafrost exists in conditions that lead to its diminishment. According to Osterkamp, subsea permafrost is a factor in the "design, construction, and operation of coastal facilities, structures founded on the seabed, artificial islands, sub-sea pipelines, and wells drilled for exploration and production." It also contains gas hydrates in places, which are a "potential abundant source of energy" but may also destabilize as subsea permafrost warms and thaws, producing large amounts of methane gas, which is a potent greenhouse gas. Scientists report with high confidence that the extent of subsea permafrost is decreasing, and 97% of permafrost under Arctic ice shelves is currently thinning.Manifestations

Base depth

Permafrost extends to a base depth where geothermal heat from the Earth and the mean annual temperature at the surface achieve an equilibrium temperature of 0 °C. The base depth of permafrost reaches in the northern Lena River, Lena and Yana River basins inSiberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

.

The geothermal gradient is the rate of increasing temperature with respect to increasing depth in the Earth's interior. Away from tectonic plate boundaries, it is about 25–30 °C/km (124–139 °F/mi) near the surface in most of the world. It varies with the thermal conductivity of geologic material and is less for permafrost in soil than in bedrock.

Calculations indicate that the time required to form the deep permafrost underlying Prudhoe Bay, Alaska was over a half-million years. This extended over several glacial and interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene and suggests that the present climate of Prudhoe Bay is probably considerably warmer than it has been on average over that period. Such warming over the past 15,000 years is widely accepted. The table to the right shows that the first hundred metres of permafrost forms relatively quickly but that deeper levels take progressively longer.

Massive ground ice

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice, aufeis (stranded river ice) and—probably the most prevalent—buried glacial ice.

Intrasedimental ice forms by in-place freezing of subterranean waters and is dominated by segregational ice which results from the crystallizational differentiation taking place during the freezing of wet sediments, accompanied by water migrating to the freezing front.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada and also includes intrusive and injection ice.

Arctic permafrost has been diminishing for decades. Globally, permafrost warmed by about between 2007 and 2016, with stronger warming observed in the continuous permafrost zone relative to the discontinuous zone. The consequence is thawing soil, which may be weaker, and release of methane, which contributes to an increased rate of global warming as part of a climate change feedback, feedback loop caused by microbial decomposition. Wetlands drying out from drainage or evaporation compromises the ability of plants and animals to survive. When permafrost continues to diminish, many climate change scenarios will be amplified. In areas where permafrost is high, nearby human infrastructure may be damaged severely by the thawing of permafrost. It is believed that Permafrost carbon cycle, carbon storage in permafrost globally is approximately 1600 gigatons; equivalent to twice the atmospheric pool.

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as ''massive'' ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter of at least 10 m.

First recorded North American observations were by European scientists at Canning River, Alaska in 1919.

Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Kh. P. Laptev, respectively.

Two categories of massive ground ice are ''buried surface ice'' and ''intrasedimental ice''

(also called ''constitutional ice'').

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice, aufeis (stranded river ice) and—probably the most prevalent—buried glacial ice.

Intrasedimental ice forms by in-place freezing of subterranean waters and is dominated by segregational ice which results from the crystallizational differentiation taking place during the freezing of wet sediments, accompanied by water migrating to the freezing front.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada and also includes intrusive and injection ice.

Arctic permafrost has been diminishing for decades. Globally, permafrost warmed by about between 2007 and 2016, with stronger warming observed in the continuous permafrost zone relative to the discontinuous zone. The consequence is thawing soil, which may be weaker, and release of methane, which contributes to an increased rate of global warming as part of a climate change feedback, feedback loop caused by microbial decomposition. Wetlands drying out from drainage or evaporation compromises the ability of plants and animals to survive. When permafrost continues to diminish, many climate change scenarios will be amplified. In areas where permafrost is high, nearby human infrastructure may be damaged severely by the thawing of permafrost. It is believed that Permafrost carbon cycle, carbon storage in permafrost globally is approximately 1600 gigatons; equivalent to twice the atmospheric pool.

Historical changes

Thaw

By definition, permafrost is ground that remains frozen for two or more years. The ground can consist of many substrate materials, including bedrock, sediment, organic matter, water or ice. Frozen ground is that which is below the freezing point of water, whether or not water is present in the substrate. Ground ice is not always present, as may be the case with nonporous bedrock, but it frequently occurs and may be present in amounts exceeding the potential Phreatic zone, hydraulic saturation of the thawed substrate. During thaw, the ice content of the soil melts and, as the water drains or evaporates, causes the soil structure to weaken and sometimes become viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. Thawing can also influence the rate of change of soil gases with the atmosphere. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the Drunken trees, random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas.Effect on slope stability

Over the past century, an increasing number of alpine rock slope failure events in mountain ranges around the world have been recorded. It is expected that the high number of structural failures is due to permafrost thawing, which is thought to be linked to climate change. Permafrost thawing is thought to have contributed to the 1987 Val Pola landslide that killed 22 people in the Italian Alps. In mountain ranges, much of the structural stability can be attributed to glaciers and permafrost. As climate warms, permafrost thaws, which results in a less stable mountain structure, and ultimately more slope failures. McSaveney reported massive rock and ice falls (up to 11.8 million m3), earthquakes (up to 3.9 Richter), floods (up to 7.8 million m3 water), and rapid rock-ice flow to long distances (up to 7.5 km at 60 m/s) caused by “instability of slopes” in high mountain permafrost. Instability of slopes in permafrost at elevated temperatures near freezing point in warming permafrost is related to effective stress and buildup of pore-water pressure in these soils. Kia and his co-inventors invented a new filter-less rigid piezometer (FRP) for measuring pore-water pressure in partially frozen soils such as warming permafrost soils. They extended the use of effective stress concept to partially frozen soils for use in slope stability analysis of warming permafrost slopes. The use of effective stress concept has many advantages such as ability to extend the concepts of "Critical State Soil Mechanics" into frozen ground engineering. In high mountains rockfalls may be caused by thawing of rock masses with permafrost.Frozen debris lobes

According to the University of Alaska Fairbanks, frozen debris lobes (FDLs) are "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice that occur in permafrost. As of December 2021, there were 43 frozen debris lobes identified in the southern Brooks Range along the Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) corridor and the main highway linking Interior Alaska and the Alaska North Slope—the Dalton Highway. By 2012, some FDLs measured over in width, in height, and in length. Based on measurements of a frozen debris-lobe southern Brooks Range in Alaska taken from 2008 to 2010, researchers found accelerated movement as ice in deeper layers of soil melted with rising temperatures. Ice within the soil melts, causing loss of soil strength, accelerated movement, and potential debris flows. They raised concerns of a future potential hazard of one debris lobe to both the Trans Alaska Pipeline System and the main highway linking Interior Alaska and the North Slope—Dalton Highway.Ecological consequences

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains 1700 billion tons of organic material equaling almost half of all organic material in all soils. This pool was built up over thousands of years and is only slowly degraded under the cold conditions in the Arctic. The amount of carbon sequestered in permafrost is four times the carbon that has been released to the atmosphere due to human activities in modern time. One manifestation of this is yedoma, which is an organic-rich (about 2% carbon by mass) Pleistocene-age loess permafrost with ice content of 50–90% by volume. Formation of permafrost has significant consequences for ecological systems, primarily due to constraints imposed upon rooting zones, but also due to limitations on den and burrow geometries for fauna requiring subsurface homes. Secondary effects impact species dependent on plants and animals whose habitat is constrained by the permafrost. One of the most widespread examples is the dominance of black spruce in extensive permafrost areas, since this species can tolerate rooting pattern constrained to the near surface. The number of bacteria in permafrost soil varies widely, typically from 1 to 1000 million per gram of soil. Most of these bacteria and fungi in permafrost soil cannot be cultured in the laboratory, but the identity of the microorganisms can be revealed by DNA-based techniques. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment.Climate change feedback

Preservation of organisms in permafrost

Microbes

Scientists predict that up to 1021 microbes, including fungi and bacteria in addition to viruses, will be released from melting ice per year. Often, these microbes will be released directly into the ocean. Due to the migratory nature of many species of fish and birds, it is possible that these microbes have a high transmission rate. Permafrost in eastern Switzerland was analyzed by researchers in 2016 at an alpine permafrost site called “Muot-da-Barba-Peider”.This site had a diverse microbial community with various bacteria and eukaryotic groups present. Prominent bacteria groups included phylum Acidobacteriota, Actinomycetota, AD3, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexota, Gemmatimonadota, OD1, Nitrospirota, Planctomycetota, Pseudomonadota, and Verrucomicrobiota. Prominent eukaryotic fungi included Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Zygomycota. In the present species, scientists observed a variety of adaptations for sub-zero conditions, including reduced and anaerobic metabolic processes. A 2016 outbreak of anthrax in the Yamal Peninsula is believed to be due to thawing permafrost. Also present in Siberian permafrost are two species of virus: Pithovirus, Pithovirus sibericum and Mollivirus sibericum. Both of these are approximately 30,000 years old and considered giant viruses due to the fact that they are larger in size than most bacteria and have genomes larger than other viruses. Both viruses are still infective, as seen by their ability to infect Acanthamoeba, a genus of amoebas. Freezing at low temperatures has been shown to preserve the infectivity of viruses. Caliciviruses, influenza A, and enteroviruses (ex. Polioviruses, echoviruses, Coxsackie viruses) have all been preserved in ice and/or permafrost. Scientists have determined three characteristics necessary for a virus to successfully preserve in ice: high abundance, ability to transport in ice, and ability to resume disease cycles upon being released from ice. A direct infection from permafrost or ice to humans has not been demonstrated; such viruses are typically spread through other organisms or abiotic mechanisms. A study of late Pleistocene Siberian permafrost samples from Kolyma Lowland (an east siberian lowland) used DNA isolation and gene cloning (specifically 16S rRNA genes) to determine which phyla these microorganisms belonged to. This technique allowed a comparison of known microorganisms to their newly discovered samples and revealed eight phylotypes, which belonged to the phyla Actinomycetota and Pseudomonadota.Plants

In 2012, Russian researchers proved that permafrost can serve as a natural repository for ancient life forms by reviving of ''Silene stenophylla'' from 30,000 year old tissue found in an Last Glacial Period, Ice Age squirrel burrow in the Siberian permafrost. This is the oldest plant tissue ever revived. The plant was fertile, producing white flowers and viable seeds. The study demonstrated that tissue can survive ice preservation for tens of thousands of years.Extraterrestrial permafrost

Other issues

TheInternational Permafrost Association

The International Permafrost Association (IPA), founded in 1983, has as its objectives to foster the dissemination of knowledge concerning permafrost and to promote cooperation among persons and national or international organisations engaged in ...

(IPA) is an integrator of issues regarding permafrost. It convenes International Permafrost Conferences, undertakes special projects such as preparing databases, maps, bibliographies, and glossaries, and coordinates international field programmes and networks. Among other issues addressed by the IPA are: Problems for construction on permafrost owing to the change of soil properties of the ground on which structures are placed and the biological processes in permafrost, e.g. the preservation of organisms frozen ''in situ''.

Construction on permafrost

Yakutsk is one of two large cities in the world built in areas of continuous permafrost—that is, where the frozen soil forms an unbroken, below-zero sheet. The other is Norilsk, in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. Building on permafrost is difficult because the heat of the building (or pipeline transport, pipeline) can warm the permafrost and destabilize the structure. Warming can result in thawing of the soil and its consequent weakening of support for a structure as the ice content turns to water; alternatively, where structures are built on piles, warming can cause movement through Creep (deformation), creep because of the change of friction on the piles even as the soil remains frozen. Three common solutions include: using foundation (architecture), foundations on wood Deep foundation, piles, a technique pioneered by Soviet engineer Mikhail Kim in Norilsk; building on a thick gravel pad (usually 1–2 metres/3.3–6.6 feet thick); or using anhydrous ammonia heat pipes. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System uses Heat pipe#Permafrost cooling, heat pipes built into vertical supports to prevent the pipeline from sinking and the Qingzang railway in Tibet employs a variety of methods to keep the ground cool, both in areas with Frost heaving#Frost-susceptible soils, frost-susceptible soil. Permafrost may necessitate special enclosures for buried utilities, called "Utility tunnel#In Arctic towns, utilidors". The Melnikov Permafrost Institute in Yakutsk, found that the sinking of large buildings into the ground can be prevented by using pile foundations extending down to or more. At this depth the temperature does not change with the seasons, remaining at about . Thawing permafrost represents a threat to industrial infrastructure. In May 2020 thawing permafrost at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's Thermal Power Plant No. 3 caused an oil storage tank to collapse, spilling 6,000 tonnes of diesel into the land, 15,000 into the water. The rivers Ambarnaya, Daldykan and many smaller rivers were polluted. The pollution reached the lake Pyasino that is important to the water supply of the entire Taimyr Peninsula. State of emergency at the federal level was declared. Many buildings and infrastructure are built on permafrost, which cover 65% of Russian territory, and all those can be damaged as it thaws. The 2020 Norilsk oil spill has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history. The thawing can also cause leakage of toxic elements from sites of buried toxic waste. There is no ground water available in an area underlain with permafrost. Any substantial settlement or installation needs to make some alternative arrangement to obtain water.See also

*Global Terrestrial Network for PermafrostPleistocene & Permafrost Foundation

References

External links

Permafrostwatch

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Infographics about permafrost

Center for Permafrost

(Alfred Wegener Institute) {{Authority control Permafrost, Geography of the Arctic Geomorphology Montane ecology Patterned grounds Pedology Periglacial landforms 1940s neologisms Cryosphere