The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being b ...

,

King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

and

Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 by ...

. It began toward the end of the

Reconquista and was intended to maintain

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

orthodoxy in their kingdoms and to replace the

Medieval Inquisition, which was under

Papal control. It became the most substantive of the three different manifestations of the wider

Catholic Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

along with the

Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, respons ...

and

Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition ( Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

. The "Spanish Inquisition" may be defined broadly as operating in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the

Canary Islands, the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. According to modern estimates, around 150,000 people were prosecuted for various offences during the three-century duration of the Spanish Inquisition, of whom between 3,000 and 5,000 were executed (~2.7% of all cases).

[Data for executions for witchcraft: And see ]Witch trials in Early Modern Europe

Witch trials in the early modern period saw that between 1400 to 1782, around 40,000 to 60,000 were killed due to suspicion that they were practicing witchcraft. Some sources estimate that a total of 100,000 trials occurred at its maximum for a s ...

for more detail.

The Inquisition was originally intended primarily to identify

heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

among those who converted from

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

and

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

to Catholicism. The regulation of the faith of newly converted Catholics was intensified after the

royal decrees issued in 1492 and 1502 ordering

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

to convert to Catholicism or leave

Castile, resulting in hundreds of thousands of

forced conversions

Forced conversion is the adoption of a different religion or the adoption of irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which ...

, the persecution of ''

converso

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

s'' and ''

morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

s'', and the

mass expulsions of Jews and

of Muslims from Spain.

The Inquisition was abolished in 1834, during the reign of

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

, after a period of declining influence in the preceding century.

Previous Inquisitions

The

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances ...

was created through

papal bull, ''

Ad Abolendam

(; full title in la, Ad abolendam diversam haeresium pravitatem, lit=To abolish diverse malignant heresies) was a decretal and bull of Pope Lucius III, written at Verona and issued 4 November 1184. It was issued after the Council of Verona sett ...

'', issued at the end of the 12th century by

Pope Lucius III

Pope Lucius III (c. 1097 – 25 November 1185), born Ubaldo Allucingoli, reigned from 1 September 1181 to his death in 1185. Born of an aristocratic family of Lucca, prior to being elected pope, he had a long career as a papal diplomat. His p ...

to combat the

Albigensian heresy in southern France. There were a large number of tribunals of the

Papal Inquisition in various European kingdoms during the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

through different diplomatic and political means. In the

Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

, a tribunal of the Papal Inquisition was established by the statute of ''Excommunicamus'' of Pope

Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decr ...

, in 1232, during the era of the Albigensian heresy, as a condition for peace with Aragon. The Inquisition was ill-received by the Aragonese, which led to prohibitions against insults or attacks on it. Rome was particularly concerned that the Iberian peninsula's large Muslim and Jewish population would have a 'heretical' influence on the Catholic population. Rome pressed the kingdoms to accept the Papal Inquisition after Aragon. Navarra conceded in the 13th century and Portugal by the end of the 14th, though its 'Roman Inquisition' was famously inactive. Castile refused steadily, trusting in its prominent position in Europe and its military power to keep the Pope's interventionism in check. By the end of the Middle Ages,

England, due to distance and voluntary compliance, and the

Castile (future part of Spain), due to resistance and power, were the only Western European kingdoms to successfully resist the establishment of the Inquisition in their realms.

Medieval Inquisition in Aragon

Although

Raymond of Penyafort

Raymond of Penyafort ( ca, Sant Ramon de Penyafort, ; es, San Raimundo de Peñafort; 1175 – 6 January 1275) was a Catalan Dominican friar in the 13th century, who compiled the Decretals of Gregory IX, a collection of canonical laws tha ...

was not an inquisitor,

James I of Aragon

James I the Conqueror ( es, Jaime el Conquistador, ca, Jaume el Conqueridor; 2 February 1208 – 27 July 1276) was King of Aragon and Lord of Montpellier from 1213 to 1276; King of Majorca from 1231 to 1276; and Valencia from 1238 to 12 ...

had often consulted him on questions of law regarding the practices of the Inquisition in the king's domains since Penyafort was a canon lawyer and royal advisor.

... e lawyer's deep sense of justice and equity, combined with the worthy Dominican's sense of compassion, allowed him to steer clear of the excesses that were found elsewhere in the formative years of the inquisitions into heresy.

Despite its early implantation, the Papal Inquisition was greatly resisted within the Crown of Aragon by both population and monarchs. With time, its importance was diluted, and, by the middle of the fifteenth century, it was almost forgotten although still there according to the law.

Regarding the living conditions of minorities, the kings of Aragon and other monarchies imposed some discriminatory taxation of religious minorities, so false conversions were a way of tax evasion.

In addition to the above discriminatory legislation, Aragon had laws specifically targeted at protecting minorities. For example, crusaders attacking Jewish or Muslim subjects of the King of Aragon while on their way to fight in the reconquest were punished with death by hanging. Up to the 14th century, the census and wedding records show an absolute lack of concern with avoiding intermarriage or blood mixture. Such laws were now common in most of central Europe. Both the Roman Inquisition and neighbouring Christian powers showed discomfort with Aragonese law and lack of concern with ethnicity, but to little effect.

High-ranking officials of Jewish religion were not as common as in Castile, but were not unheard of either.

Abraham Zacuto

Abraham Zacuto ( he, , translit=Avraham ben Shmuel Zacut, pt, Abraão ben Samuel Zacuto; 12 August 1452 – ) was a Castilian astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, rabbi and historian who served as Royal Astronomer to King John II of Portugal.

...

was a professor at the university of Cartagena.

Vidal Astori Vidal Astori, born in Valencia in the 15th century, was a Sephardic silversmith and merchant. He worked for the court of Ferdinand the Catholic between 1467 and 1469. With time he would reach the prestigious rank of "silversmith of the king," a stat ...

was the royal silversmith for

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

and conducted business in his name. And King Ferdinand himself was said to have remote Jewish ancestry on his mother's side.

Medieval Inquisition in Castile

There was never a tribunal of the Papal Inquisition in

Castile, nor any inquisition during the Middle Ages. Members of the

episcopate

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

were charged with surveillance of the faithful and punishment of transgressors, always under the direction of the king.

During the Middle Ages in Castile, the Catholic ruling class and the population paid little or no attention to heresy. Castile did not have the proliferation of anti-Jewish pamphlets as England and France did during the 13th and 14th centuries—and those that have been found were modified, watered-down versions of the original stories. Jews and Muslims were tolerated and generally allowed to follow their traditional customs in domestic matters.

The legislation regarding Muslims and Jews in Castilian territory varied greatly, becoming more intolerant during the period of great instability and dynastic wars that occurred by the end of the 14th century. Castilian law is particularly difficult to summarize since, due to the model of the free Royal Villas, mayors and the population of border areas had the right to create their own

fueros

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

(law) that varied from one villa to the next. In general, the Castilian model was parallel to the initial model of Islamic Spain. Non-Catholics were subject to discriminatory legislation regarding taxation and some other specific discriminatory legislation—such as a prohibition on wearing silk or "flashy clothes"

[Suárez Fernández, Luis (2012). ''La expulsión de los judíos. Un problema europeo''. Barcelona: Ariel.]—that varied from county to county, but were otherwise left alone. Forced conversion of minorities was against the law, and so was the belief in the existence of witchcraft, oracles or similar superstitions. In general, all "people from the book" were permitted to practice their own customs and religions as far as they did not attempt proselytizing on the Christian population. Jews particularly had surprising freedoms and protections compared with other areas of Europe and were allowed to hold high public offices such as the counselor, treasurer or secretary for the crown.

During most of the medieval period, intermarriage with converts was allowed and encouraged. Intellectual cooperation between religions was the norm in Castile. Some examples are the

Toledo School of Translators

The Toledo School of Translators ( es, Escuela de Traductores de Toledo) is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the Judeo-Islamic philosophies and scientific w ...

from the 11th century. Jews and Moors were allowed to hold high offices in the administration (see

Abraham Seneor

Abraham Seneor or Abraham Senior (Segovia 1412 - 1493) was a Sephardic rabbi, banker, politician, patriarch of the Coronel family and last Crown rabbi of Castile, a senior member of the Castilian hacienda (almojarife of the Castile or royal admi ...

,

Samuel HaLevi Abulafia,

Isaac Abarbanel

Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel ( he, יצחק בן יהודה אברבנאל; 1437–1508), commonly referred to as Abarbanel (), also spelled Abravanel, Avravanel, or Abrabanel, was a Portuguese Jewish statesman, philosopher, Bible commentato ...

, López de Conchillos,

Miguel Pérez de Almazán

Miguel Pérez de Almazán (Calatayud, Aragón, ? - Madrid, Castile, 1514) was a Spanish hidalgo.

Life

The son of converted Jews, Almazán served as the private secretary of Ferdinand the Catholic, and later the Royal secretary of the Catholi ...

, Jaco Aben Nunnes and Fernando del Pulgar).

A tightening of the laws to protect the right of Jews to collect loans during the Medieval Crisis was one of the causes of the revolt against

Peter the Cruel and catalyst of the anti-semitic episodes of 1391 in Castile, a kingdom that had shown no significant antisemitic backlash to the black death and drought crisis of the early 14th century. Even after the sudden increase in hostility towards other religions that the kingdom experienced after the 14th-century crisis, which clearly worsened the living conditions of non-Catholics in Castile, it remained one of the most tolerant kingdoms in Europe.

The kingdom had serious tensions with Rome regarding the Church's attempts to extend its authority into the kingdom. A focus of conflict was Castilian resistance to truly abandon the

Mozarabic Rite, and the refusal to grant Papal control over Reconquest land (a request Aragon and Portugal conceded). These conflicts added to a strong resistance to allowing the creation of an Inquisition, and the kingdom's general willingness to accept heretics seeking refuge from prosecution in France.

Creation of the Spanish Inquisition

There are several hypotheses of what prompted the creation of the tribunal after

centuries of tolerance (within the context of medieval Europe).

The "Too Multi-Religious" hypothesis

The Spanish Inquisition is interpretable as a response to the multi-religious nature of Spanish society following the

reconquest of the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

from the Muslim

Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

. After invading in 711, the Moors controlled large areas of the Iberian Peninsula until 1250; afterwards they were restricted to

Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

, which fell in 1492. The Reconquista did not result in the total expulsion of Muslims from Spain, since they, along with Jews, were tolerated by the ruling Christian elite. Large cities, especially

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

,

Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

, and

Barcelona, had significant Jewish populations centered on

Juderia, but in the coming years the Muslims became increasingly alienated and relegated from power centers.

Post-reconquest medieval Spain has been characterized by

Américo Castro as a society of relatively peaceful co-existence (''convivencia'') punctuated by occasional conflict among the ruling Catholics and the Jews and Muslims. As historian Henry Kamen notes, the "so-called convivencia was always a relationship between unequals." Despite their legal inequality, there was a long tradition of Jewish service to the Crown of Aragon, and Jews occupied many important posts, both religious and political. Castile itself had an unofficial

rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

. Ferdinand's father

John II named the Jewish

Abiathar Crescas Court

Astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either obse ...

.

Anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

attitudes increased all over Europe during the late 13th century and throughout the 14th century. England and France expelled their

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

populations in 1290 and 1306 respectively. At the same time, during the

Reconquista, Spain's anti-Jewish sentiment steadily increased. This prejudice climaxed in the summer of 1391 when violent anti-Jewish riots broke out in Spanish cities like

Barcelona. To linguistically distinguish them from non-converted or long-established Catholic families, new converts were called

conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

, or New Catholics. This event must be understood in the context of the fierce civil war and new politics that

Peter the Cruel had brought to the land, and not be confused with spontaneous anti-semitic reactions to the plague seen in northern Europe.

According to Don

Hasdai Crescas

Hasdai ben Abraham Crescas (; he, חסדאי קרשקש; c. 1340 in Barcelona – 1410/11 in Zaragoza) was a Spanish-Jewish philosopher and a renowned halakhist (teacher of Jewish law). Along with Maimonides ("Rambam"), Gersonides ("Ralbag"), ...

, persecution against Jews began in earnest in

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

in 1391, on the 1st day of the lunar month

Tammuz

Dumuzid or Tammuz ( sux, , ''Dumuzid''; akk, Duʾūzu, Dûzu; he, תַּמּוּז, Tammûz),; ar, تمّوز ' known to the Sumerians as Dumuzid the Shepherd ( sux, , ''Dumuzid sipad''), is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with shep ...

(June).

[Letter of Hasdai Crescas, ''Shevaṭ Yehudah'' by Solomon ibn Verga (ed. Dr. M. Wiener), Hannover 1855, pp. 128–130 (pp. 138–140 i]

PDF

; Fritz Kobler, ''Letters of the Jews through the Ages'', London 1952, pp. 272–75; ; Solomon ibn Verga

''Shevaṭ Yehudah'' (The Sceptre of Judah)

Lvov 1846, p. 76 in PDF. From there the violence spread to

Córdoba, and by the 17th day of the same lunar month, it had reached

Toledo (called then by Jews after its Arabic name "Ṭulayṭulah") in the region of

Castile. Then the violence spread to

Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Ba ...

and by the 1st day of the lunar month

Elul

Elul ( he, אֱלוּל, Standard ''ʾElūl'', Tiberian ''ʾĔlūl'') is the twelfth month of the Jewish civil year and the sixth month of the ecclesiastical year on the Hebrew calendar. It is a month of 29 days. Elul usually occurs in August– ...

it had also reached the Jews of

Barcelona in

Catalonia, where the slain were estimated at two-hundred and fifty. Indeed, many Jews who resided in the neighboring provinces of

Lérida

Lleida (, ; Spanish: Lérida ) is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital city of the province of Lleida.

Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Central Depression. It is also the capital city of the Segrià comarca, as ...

and Gironda and in the kingdom of

València

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

had also been affected, as were also the Jews of

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mu ...

(Andalucía). While many died a martyr's death, others converted to save themselves.

Encouraged by the preaching of

Ferrand Martínez

Ferrand Martinez (fl. 14th century) was a Spanish cleric and archdeacon of Écija, most noted for being an antisemitic agitator whom historians cite as the prime mover behind the series of pogroms against the Spanish Jews in 1391, beginning in the ...

,

Archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that of most ...

of

Ecija, the general unrest affected nearly all of the Jews in Spain, during which time an estimated 200,000 Jews changed their religion or else concealed their religion, becoming known in Hebrew as

Anusim

Anusim ( he, אֲנוּסִים, ; singular male, anús, he, אָנוּס ; singular female, anusáh, , meaning "coerced") is a legal category of Jews in ''halakha'' (Jewish law) who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will, typically ...

, meaning, "those who are compelled

o hide their religion" Only a handful of the more principal persons of the Jewish community, those who had found refuge among the viceroys in the outlying towns and districts, managed to escape.

Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force: a person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism. After the public violence, many of the converted "felt it safer to remain in their new religion." Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as ''

conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

'' or ''New Christians''. Many ''conversos'', now freed from the anti-Semitic restrictions imposed on Jewish employment, attained important positions in fifteenth-century Spain, including positions in the government and in the Church. Among many others, physicians

Andrés Laguna and

Francisco López de Villalobos (Ferdinand's court physician), writers

Juan del Enzina,

Juan de Mena

Juan de Mena (1411–1456) was one of the most significant Spanish poets of the fifteenth century. He was highly regarded at the court of Juan II de Castilla, who appointed him ''veinticuatro'' (one of twenty-four aldermen) of Córdoba, ''sec ...

,

Diego de Valera and Alonso de Palencia, and bankers

Luis de Santángel

Luis de Santángel (died 1498) was a third generation ''converso'' in Spain during the late fifteenth century. Santángel worked as ''escribano de ración'' to King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Spain which left him in charge of the Royal ...

and Gabriel Sánchez (who financed the voyage of

Christopher Columbus) were all ''conversos''. ''Conversos''—not without opposition—managed to attain high positions in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, at times becoming severe detractors of Judaism. Some even received titles of nobility and, as a result, during the following century some works attempted to demonstrate many nobles of Spain were descended from Israelites.

The "Enforcement Across Borders" hypothesis

According to this hypothesis, the Inquisition was created to standardize the variety of laws and many jurisdictions Spain was divided into. It would be an administrative program analogous to the

Santa Hermandad

Santa Hermandad (, "holy brotherhood") was a type of military peacekeeping association of armed individuals, which became characteristic of municipal life in medieval Spain, especially in Castile. Modern hermandades in Spain, some of which evo ...

(the "Holy Brotherhood", a law enforcement body, answering to the crown, that prosecuted thieves and criminals across counties in a way local county authorities could not, ancestor to the

Guardia Civil

The Civil Guard ( es, Guardia Civil, link=no; ) is the oldest law enforcement agency in Spain and is one of two national police forces. As a national gendarmerie force, it is military in nature and is responsible for civil policing under the au ...

), an institution that would guarantee uniform prosecution of crimes against royal laws across all local jurisdictions.

The Kingdom of Castile had been prosperous and successful in Europe thanks in part to the unusual authority and control the king exerted over the nobility, which ensured political stability and kept the kingdom from being weakened by in-fighting (as was the case in England, for example). Under the

Trastámara dynasty, both kings of Castile and Aragon had lost power to the great nobles, who now formed dissenting and conspiratorial factions. Taxation and varying privileges differed from county to county, and powerful noble families constantly extorted the kings to attain further concessions, particularly in Aragon.

The main goals of the reign of the Catholic Monarchs were to unite their two kingdoms and strengthen royal influence to guarantee stability. In pursuit of this, they sought to further unify the laws of their realms and reduce the power of the nobility in certain local areas. They attained this partially by raw military strength by creating a combined army between the two of them that could outmatch the army of most noble coalitions in the Peninsula. It was impossible to change the entire laws of both realms by force alone, and due to reasonable suspicion of one another the monarchs kept their kingdoms separate during their lifetimes. The only way to unify both kingdoms and ensure that Isabella, Ferdinand, and their descendants maintained the power of both kingdoms without uniting them in life was to find, or create, an executive, legislative and judicial arm directly under the Crown empowered to act in both kingdoms. This goal, the hypothesis goes, might have given birth to the Spanish Inquisition.

The religious organization to oversee this role was obvious: Catholicism was the only institution common to both kingdoms, and the only one with enough popular support that the nobility could not easily attack it. Through the Spanish Inquisition, Isabella and Ferdinand created a personal police force and personal code of law that rested above the structure of their respective realms without altering or mixing them, and could operate freely in both. As the Inquisition had the backing of both kingdoms, it would exist independent of both the nobility and local interests of either kingdom.

According to this view, the prosecution of heretics would be secondary, or simply not considered different, from the prosecution of conspirators, traitors, or groups of any kind who planned to resist royal authority. At the time, royal authority rested on divine right and on oaths of loyalty held before God, so the connection between religious deviation and political disloyalty would appear obvious. This hypothesis is supported by the disproportionately high representation of the nobility and high clergy among those investigated by the Inquisition, as well as by the many administrative and civil crimes the Inquisition oversaw. The Inquisition prosecuted the counterfeiting of royal seals and currency, ensured the effective transmission of the orders of the kings, and verified the authenticity of official documents traveling through the kingdoms, especially from one kingdom to the other. See "Non-Religious Crimes".

The "Placate Europe" hypothesis

At a time when most of Europe had already

expelled the Jews from the Christian kingdoms, the "dirty blood" of Spaniards was met with open suspicion and contempt by the rest of Europe. As the world became smaller and foreign relations became more relevant to stay in power, this foreign image of "being the seed of Jews and Moors" may have become a problem. In addition, the coup that allowed Isabella to take the throne from

Joana of Avis and the Catholic Monarchs to marry had estranged Castile from Portugal, its historical ally, and created the need for new relationships. Similarly, Aragon's ambitions lay in control of the Mediterranean and the defense against France. As their

policy of royal marriages proved, the Catholic Monarchs were deeply concerned about France's growing power and expected to create strong dynastic alliances across Europe. In this scenario, the Iberian reputation of being too tolerant was a problem.

Despite the prestige earned through the reconquest (

reconquista), the foreign image of Spaniards coexisted with an almost universal image of heretics and "bad Christians", due to the long coexistence between the three religions they had accepted in their lands. Anti-Jewish stereotypes created to justify or prompt the expulsion and expropriation of the European Jews were also applied to Spaniards in most European courts, and the idea of them being "greedy, gold-thirsty, cruel and violent" due to the "Jewish and Moorish blood" was prevalent in Europe before America was discovered by Europeans. Chronicles by foreign travelers circulated through Europe, describing the tolerant ambiance reigning in the court of Isabella and Ferdinand, and how Moors and Jews were free to go about without anyone trying to convert them. Past and common clashes between the Pope and the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula regarding the Inquisition in Castile's case and regarding South Italy in Aragon's case, also reinforced their image of heretics in the international courts. These accusations and images could have direct political and military consequences at the time, especially considering that the union of two powerful kingdoms was a particularly delicate moment that could prompt the fear and violent reactions from neighbors, even more if combined with the expansion of the Ottoman Turks on the Mediterranean.

The creation of the Inquisition and the expulsion of both Jews and Moriscos may have been part of a strategy to whitewash the image of Spain and ease international fears regarding Spain's allegiance. In this scenario, the creation of the Inquisition could have been part of the Catholic's Monarch strategy to " turn" away from African allies and "towards" Europe, a tool to turn both actual Spain and the Spanish image more European and improve relations with the Pope.

[Elvira, Roca Barea María, and Arcadi Espada. Imperiofobia Y Leyenda Negra: Roma, Rusia, Estados Unidos Y El Imperio Español. Madrid: Siruela, 2017]

The "Ottoman Scare" hypothesis

No matter if any of the previous hypotheses were already operating in the minds of the monarchs, the alleged discovery of Morisco plots to support a possible Ottoman invasion were crucial factors in their decision to create the Inquisition.

At this time, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was in rapid expansion and making its power noticeable in the Mediterranean and North Africa. At the same time, the Aragonese Mediterranean Empire was crumbling under debt and war exhaustion. Ferdinand reasonably feared that he would not be capable of repelling an Ottoman attack to Spain's shores, especially if the Ottomans had internal help. The regions with the highest concentration of Moriscos were those close to the common naval crossings between Spain and Africa. If the weakness of the Aragonese Naval Empire was combined with the resentment of the higher nobility against the monarchs, the dynastic

claims of Portugal on Castile and the two monarch's exterior politic that turned away from Morocco and other African nations in favor of Europe, the fear of a second Muslim invasion, and thus a second Muslim occupation was hardly unfounded. This fear may have been the base reason for the expulsion of those citizens who had either a religious reason to support the invasion of the Ottomans (Moriscos) or no particular religious reason to not do it (Jews). The Inquisition might have been part of the preparations to enforce these measures and ensure their effectiveness by rooting out false converts that would still pose a threat of foreign espionage.

In favor of this view there is the obvious military sense it makes, and the many early attempts of peaceful conversion and persuasion that the Monarchs used at the beginning of their reign, and the sudden turn towards the creation of the Inquisition and the edicts of expulsion when those initial attempts failed. The

conquest of Naples by the

Gran Capitan is also proof of an interest in Mediterranean expansion and re-establishment of Spanish power in that sea that was bound to generate frictions with the Ottoman Empire and other African nations. So, the Inquisition would have been created as a permanent body to prevent the existence of citizens with religious sympathies with African nations now that rivalry with them had been deemed unavoidable.

Philosophical and religious reasons

The creation of the Spanish Inquisition was consistent with the most important political philosophers of the

Florentine School

Florentine painting or the Florentine School refers to artists in, from, or influenced by the naturalistic style developed in Florence in the 14th century, largely through the efforts of Giotto di Bondone, and in the 15th century the leading scho ...

, with whom the kings were known to have contact (

Guicciardini,

Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

,

Machiavelli, Segni, Pitti, Nardi, Varchi, etc.) Both Guicciardini and Machiavelli defended the importance of centralization and unification to create a strong state capable of repelling foreign invasions, and also warned of the dangers of excessive social uniformity to the creativity and innovation of a nation. Machiavelli considered piety and morals desirable for the subjects but not so much for the ruler, who should use them as a way to unify its population. He also warned of the nefarious influence of a corrupt church in the creation of a selfish population and middle nobility, which had fragmented the peninsula and made it unable to resist either France or Aragon. German philosophers at the time were spreading the importance of a vassal sharing the religion of their lord.

The Inquisition may have just been the result of putting these ideas into practice. The use of religion as a unifying factor across a land that was allowed to stay diverse and maintain different laws in other respects, and the creation of the Inquisition to enforce laws across it, maintain said religious unity and control the local elites were consistent with most of those teachings.

Alternatively, the enforcement of Catholicism across the realm might indeed be the result of simple religious devotion by the monarchs. The recent scholarship on the expulsion of the Jews leans towards the belief of religious motivations being at the bottom of it. But considering the reports on Ferdinand's political persona, that is unlikely the only reason. Ferdinand was described, among others, by Machiavelli, as a man who didn't know the meaning of piety, but who made political use of it and would have achieved little if he had really known it. He was Machiavelli's main inspiration while writing

The Prince

''The Prince'' ( it, Il Principe ; la, De Principatibus) is a 16th-century political treatise written by Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli as an instruction guide for new princes and royals. The general theme of ''The ...

.

The "Keeping the Pope in Check" hypothesis

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church had made many attempts during the Middle Ages to take over Christian Spain politically, such as claiming the Church's ownership over all land reconquered from non-Christians (a claim that was rejected by Castille but accepted by Aragon and Portugal). In the past, the papacy had tried and partially succeeded, in forcing the

Mozarabic Rite out of Iberia. Its intervention had been pivotal for

Aragon's loss of Rosellon. The

meddling regarding Aragon's control over South Italy was even stronger historically. In their lifetime, the Catholic Monarchs had

problems with Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II ( la, Paulus II; it, Paolo II; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States

from 30 August 1464 to his death in July 1471. When his maternal uncle Eugene IV ...

, a very strong proponent of absolute authority for the church over the kings. Carrillo actively opposed them both and often used Spain's "mixed blood" as an excuse to intervene. The papacy and the monarchs of Europe had been involved in a

rivalry for power all through the high Middle Ages that Rome had already won in other powerful kingdoms like

France.

Since the legitimacy granted by the church was necessary both, especially Isabella, to stay in power, the creation of the Spanish Inquisition may have been a way to apparently concede to the Pope's demands and criticism regarding Spain's mixed religious heritage, while at the same time ensuring that the Pope could hardly force the second inquisition of his own, and at the same time create a tool to control the power of the Roman Church in Spain. The Spanish Inquisition was unique at the time because it was not led by the Pope. Once the bull of creation was granted, the head of the Inquisition was the Monarch of Spain. It was in charge of enforcing the laws of the king regarding religion and other private-life matters, not of following orders from Rome, from which it was independent. This independence allowed the Inquisition to investigate, prosecute and convict clergy for both corruptions and possible charges of treason of conspiracy against the crown (on the Pope's behalf presumably) without the Pope's intervention. The inquisition was, despite its title of "Holy", not necessarily formed by the clergy and secular lawyers were equally welcome to it. If it was an attempt at keeping Rome out of Spain, it was an extremely successful and refined one. It was a bureaucratic body that had the nominal authority of the church and permission to prosecute members of the church, which the kings could not do, while answering only to the Spanish Crown. This did not prevent the Pope from having some influence on the decisions of Spanish monarchs, but it did force the influence to be through the kings, making direct influence very difficult.

Other hypotheses

Other hypotheses that circulate regarding the Spanish Inquisition's creation include:

*Economic reasons: Since one of the penalties that the Inquisition could enforce on the convicts was the confiscation of their property, which became Crown property, it has been stated that the creation of the Inquisition was a way to finance the crown. There is no solid reason for this hypothesis to stand alone, nor for the Kings of Spain to need an institution to do this gradually instead of confiscating property through edicts, but it may be one of the reasons why the Inquisition stayed for so long. This hypothesis notes the tendency of the Inquisition to operate in large and wealthy cities and is favoured by those who consider that most of those prosecuted for practising Judaism and Islam in secret was actually innocent of it.

[The Marranos of Spain. From the late XIVth to the early XVIth Century, 1966. Ithaca, 1999] Gustav Bergenroth editor and translator of the Spanish state papers 1485–1509 believed that revenue was the incentive for Ferdinand and Isabella's decision to invite the Inquisition into Spain. Other authors point out that both monarchs were very aware of the economic consequences they would suffer from a decrease in population.

*Intolerance and racism: This argument is usually made regarding the expulsion of the Jews or the Moriscos,

and since the Inquisition was so closely interconnected with those actions can be expanded to it. It varies between those who deny that Spain was really that different from the rest of Europe regarding tolerance and openmindedness and those who argue that it used to be, but gradually the antisemitic and racist atmosphere of medieval Europe rubbed onto it. It explains the creation of the Inquisition as the result of exactly the same forces than the creation of similar entities across Europe. This view may account for the similarities between the Spanish Inquisition and similar institutions but completely fails to account for its many unique characteristics, including its time of appearance and its duration through time, so even if accepted requires the addition of some of the other hypothesis to be complete.

*Purely religious reasons: essentially this view suggests that the Catholic Monarchs created the Inquisition to prosecute heretics and sodomites "because the Bible says so". A common criticism that this view receives is that the Bible also condemns greed, hypocrisy, and adultery, but the Inquisition was not in charge of prosecuting any of those things. It also did not prosecute those who did not go to mass on Sunday or otherwise broke the Catholic rituals as far as it was out of simple laziness. Considering this double standard, its role was probably more complex and specific.

Activity of the Inquisition

Start of the Inquisition

Fray Alonso de Ojeda, a

Dominican friar from Seville, convinced

Queen Isabella of the existence of

Crypto-Judaism

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Sp ...

among

Andalusian ''

conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

'' during her stay in

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

between 1477 and 1478. A report, produced by

Pedro González de Mendoza

Pedro González de Mendoza (3 May 1428 – 11 January 1495) was a Spanish cardinal, statesman and lawyer. He served on the council of King Enrique IV of Castile and in 1467 fought for him at the Second Battle of Olmedo. In 1468 he was named bi ...

, Archbishop of Seville, and by the Segovian Dominican

Tomás de Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada (14 October 1420 – 16 September 1498), also anglicized as Thomas of Torquemada, was a Castilian Dominican friar and first Grand Inquisitor of the Tribunal of the Holy Office (otherwise known as the Spanish Inquisition). ...

—of converso family himself—corroborated this assertion.

Spanish monarchs

Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

and

Isabella requested a

papal bull establishing an inquisition in Spain in 1478.

Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV ( it, Sisto IV: 21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484), born Francesco della Rovere, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 to his death in August 1484. His accomplishments as pope include ...

granted a bull permitting the monarchs to select and appoint two or three priests over forty years of age to act as inquisitors. In 1483,

Ferdinand and Isabella

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bo ...

established a state council to administer the inquisition with the Dominican Friar

Tomás de Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada (14 October 1420 – 16 September 1498), also anglicized as Thomas of Torquemada, was a Castilian Dominican friar and first Grand Inquisitor of the Tribunal of the Holy Office (otherwise known as the Spanish Inquisition). ...

acting as its president, even though Sixtus IV protested the activities of the inquisition in

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

and its treatment of the ''conversos''. Torquemada eventually assumed the title of Inquisitor-General.

Thomas F. Madden describes the world that formed medieval politics:

"The Inquisition was not born out of the desire to crush diversity or oppress people; it was rather an attempt to stop unjust executions. Yes, you read that correctly. Heresy was a crime against the state. Roman law in the

Code of Justinian

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, t ...

made it a capital offence. Rulers, whose authority was believed to come from God, had no patience for heretics".

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

pressured Pope Sixtus IV to agree to an Inquisition controlled by the monarchy by threatening to withdraw military support at a time when the Turks were a threat to Rome. The pope issued a

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Neutering, castrated) adult male of the species ''Cattle, Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., Cattle, cows), bulls have long been an important symbol i ...

to stop the Inquisition but was pressured into withdrawing it. On 1 November 1478, Sixtus published the

Papal bull, ''Exigit Sinceras Devotionis Affectus'', through which he gave the monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors in their kingdoms. The first two inquisitors, Miguel de Morillo and

Juan de San Martín, were not named until two years later, on 27 September 1480 in

Medina del Campo

Medina del Campo is a town and municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. Part of the Province of Valladolid, it is the centre of a farming area.

History

Medina del Campo grew in importance thanks to its fairs ...

.

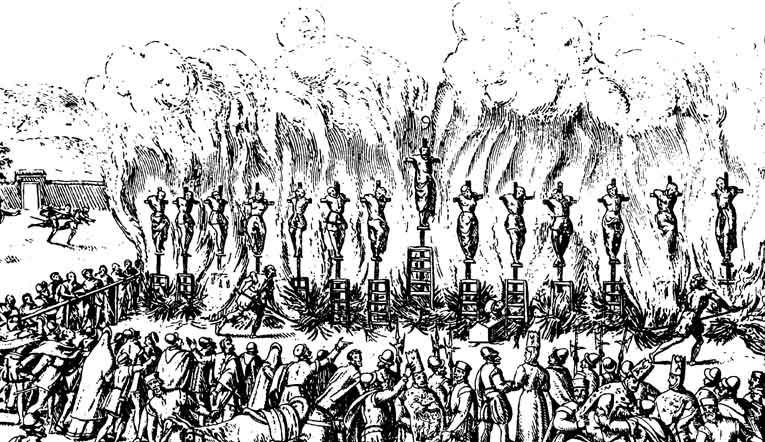

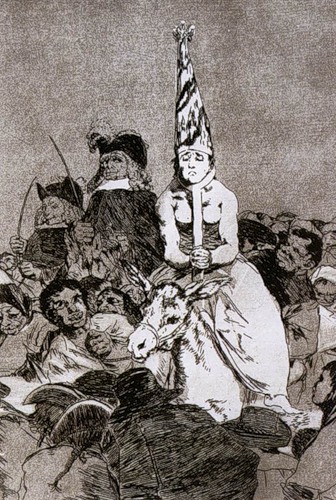

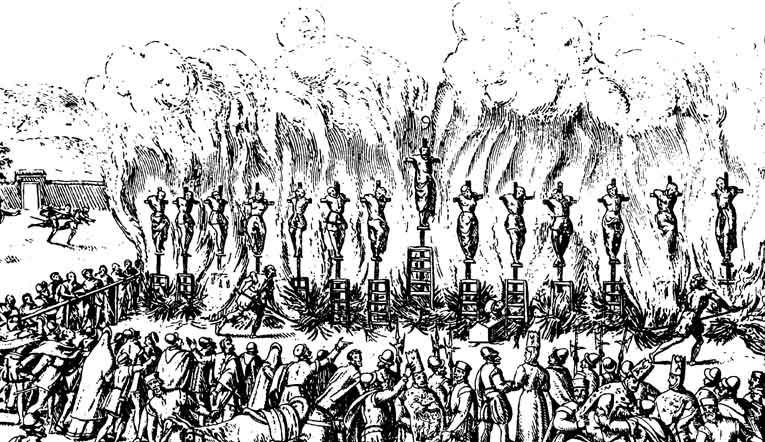

The first ''

auto-da-fé

An ''auto-da-fé'' ( ; from Portuguese , meaning 'act of faith'; es, auto de fe ) was the ritual of public penance carried out between the 15th and 19th centuries of condemned heretics and apostates imposed by the Spanish, Portuguese, or M ...

'' was held in Seville on 6 February 1481: six people were burned alive. From there, the Inquisition grew rapidly in the

Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th centu ...

. By 1492, tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities:

Ávila

Ávila (, , ) is a city of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Ávila.

It lies on the right bank of the Adaja river. Located more than 1,130 m ab ...

,

Córdoba,

Jaén,

Medina del Campo

Medina del Campo is a town and municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. Part of the Province of Valladolid, it is the centre of a farming area.

History

Medina del Campo grew in importance thanks to its fairs ...

,

Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau (''Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of t ...

,

Sigüenza

Sigüenza () is a city in the Serranía de Guadalajara comarca, Province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain.

History

The site of the ancient ''Segontia'' ('dominating over the valley') of the Celtiberian Arevaci, now called ('old tow ...

,

Toledo, and

Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

. Sixtus IV promulgated a new

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Neutering, castrated) adult male of the species ''Cattle, Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., Cattle, cows), bulls have long been an important symbol i ...

categorically prohibiting the Inquisition's extension to

Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, affirming that:

According to the book ''A History of the Jewish People'',

In 1483, Jews were expelled from all of

Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

. Though the pope wanted to crack down on abuses, Ferdinand pressured him to promulgate a new bull, threatening that he would otherwise separate the Inquisition from Church authority. Sixtus did so on 17 October 1483, naming

Tomás de Torquemada

Tomás de Torquemada (14 October 1420 – 16 September 1498), also anglicized as Thomas of Torquemada, was a Castilian Dominican friar and first Grand Inquisitor of the Tribunal of the Holy Office (otherwise known as the Spanish Inquisition). ...

Inquisidor General of Aragón, Valencia, and

Catalonia.

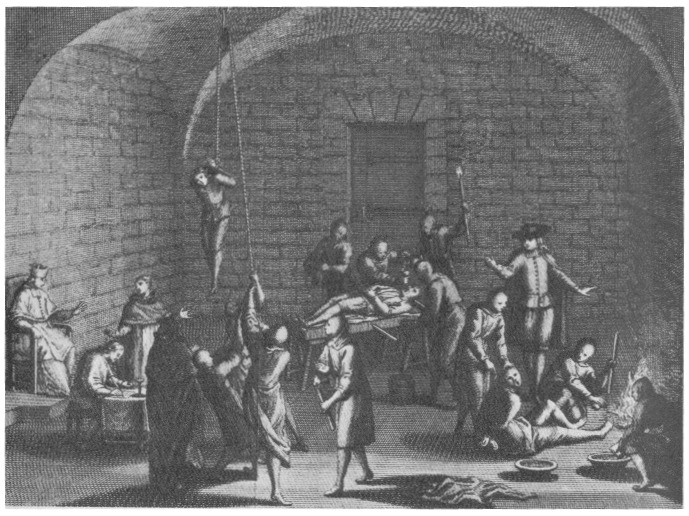

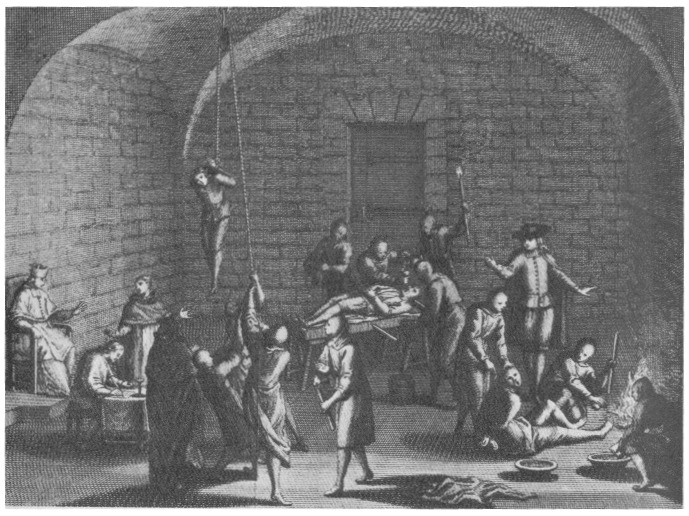

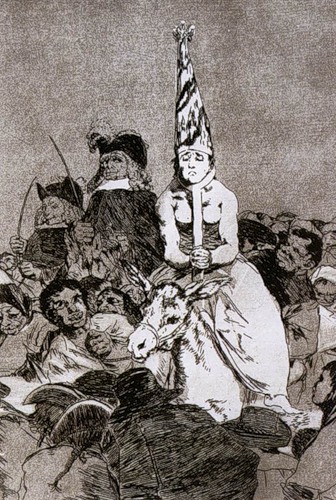

Torquemada quickly established procedures for the Inquisition. A new court would be announced with a thirty-day grace period for confessions and the gathering of accusations by neighbors. Evidence that was used to identify a crypto-Jew included the absence of chimney smoke on Saturdays (a sign the family might secretly be honoring the Sabbath) or the buying of many vegetables before Passover or the purchase of meat from a converted butcher. The court could employ

physical torture to extract confessions once the guilt of the accused had been established. Crypto-Jews were allowed to confess and do penance, although those who relapsed were executed.

In 1484, Pope

Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII ( la, Innocentius VIII; it, Innocenzo VIII; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death in July 1492. Son of th ...

attempted to allow appeals to Rome against the Inquisition, which would weaken the function of the institution as protection against the pope, but Ferdinand in December 1484 and again in 1509 decreed death and confiscation for anyone trying to make use of such procedures without royal permission.

With this, the Inquisition became the only institution that held authority across all the realms of the Spanish monarchy and, in all of them, a useful mechanism at the service of the crown. The cities of Aragón continued resisting, and even saw revolt, as in

Teruel

Teruel () is a city in Aragon, located in eastern Spain, and is also the capital of Teruel Province. It has a population of 35,675 in 2014 making it the least populated provincial capital in the country. It is noted for its harsh climate, with a ...

from 1484 to 1485. The murder of ''Inquisidor''

Pedro Arbués in

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributa ...

on 15 September 1485, caused public opinion to turn against the ''conversos'' and in favour of the Inquisition. In Aragón, the Inquisitorial courts were focused specifically on members of the powerful ''converso'' minority, ending their influence in the Aragonese administration.

The Inquisition was extremely active between 1480 and 1530. Different sources give different estimates of the number of trials and executions in this period; some estimate about 2,000 executions, based on the documentation of the ''autos-da-fé'', the great majority being ''conversos'' of Jewish origin. He offers striking statistics: 91.6% of those judged in Valencia between 1484 and 1530 and 99.3% of those judged in Barcelona between 1484 and 1505 were of Jewish origin.

False conversions

The Inquisition had jurisdiction only over Christians. It had no power to investigate, prosecute, or convict Jews, Muslims, or any open member of other religions. Anyone who was known to identify as either Jew or Muslim was outside of Inquisitorial jurisdiction and could be tried only by the King. All the inquisition could do in some of those cases was to deport the individual according to the King's law, but usually, even that had to go through a civil tribunal. The Inquisition had the authority to try only those who self-identified as Christians (initially for taxation purposes, later to avoid deportation as well) while practicing another religion de facto. Even those were treated as Christians. If they confessed or identified not as "judeizantes" but as fully practicing Jews, they fell back into the previously explained category and could not be targeted, although they would have pleaded guilty to previously lying about being Christian.

Expulsion of Jews and Jewish ''conversos''

The Spanish Inquisition had been established in part to prevent ''conversos'' from engaging in Jewish practices, which, as Christians, they were supposed to have given up. This remedy for securing the orthodoxy of ''conversos'' was eventually deemed inadequate since the main justification the monarchy gave for

formally expelling all Jews from Spain was the "great harm suffered by Christians (i.e., ''conversos'') from the contact, intercourse and communication which they have with the Jews, who always attempt in various ways to seduce faithful Christians from our Holy Catholic Faith", according to the 1492 edict.

The

Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Arago ...

, issued in January 1492, gave the choice between expulsion and conversion. It was among the few expulsion orders that allowed conversion as an alternative and is used as a proof of the religious, not racial, element of the measure. The enforcement of this decree was very unequal with the focus mainly on coastal and southern regions—those at risk of Ottoman invasion—and more gradual and ineffective enforcement towards the interior.

Historic accounts of the numbers of Jews who left Spain were based on speculation, and some aspects were exaggerated by early accounts and historians:

Juan de Mariana

Juan de Mariana, , also known as Father Mariana (25 September 1536 – 17 February 1624), was a Spanish Jesuit priest, Scholastic, historian, and member of the Monarchomachs.

Life

Juan de Mariana was born in Talavera, Kingdom of Toledo. He stu ...

speaks of 800,000 people, and

Don Isaac Abravanel of 300,000. While few reliable statistics exist for the expulsion, modern estimates based on tax returns and population estimates of communities are much lower, with Kamen stating that of a population of approximately 80,000 Jews and 200,000 ''conversos'', about 40,000 emigrated. The Jews of the kingdom of Castile emigrated mainly to Portugal (where the entire community was forcibly converted in 1497) and to North Africa. The Jews of the kingdom of Aragon fled to other Christian areas including Italy, rather than to Muslim lands as is often assumed. Although the vast majority of ''conversos'' simply assimilated into the Catholic dominant culture, a minority continued to practice Judaism in secret, gradually migrated throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, mainly to areas where Sephardic communities were already present as a result of the Alhambra Decree.

The most intense period of persecution of ''conversos'' lasted until 1530. From 1531 to 1560 the percentage of ''conversos'' among the Inquisition trials dropped to 3% of the total. There was a rebound of persecutions when a group of crypto-Jews was discovered in

Quintanar de la Orden in 1588 and there was a rise in denunciations of ''conversos'' in the last decade of the sixteenth century. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, some ''conversos'' who had fled to Portugal began to return to Spain, fleeing the persecution of the

Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition ( Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

, founded in 1536. This led to a rapid increase in the trials of crypto-Jews, among them a number of important financiers. In 1691, during a number of ''

autos-da-fé'' in

Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Ba ...

, 37 ''chuetas'', or ''conversos'' of Majorca, were burned.

During the eighteenth century, the number of ''conversos'' accused by the Inquisition decreased significantly. Manuel Santiago Vivar, tried in Córdoba in 1818, was the last person tried for being a crypto-Jew.

Expulsion of Moriscos and Morisco ''conversos''

The Inquisition searched for false or relapsed converts among the

Moriscos

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

, who had converted from

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. Beginning with a decree on 14 February 1502, Muslims in Granada had to choose between conversion to Christianity or expulsion.

In the Crown of Aragon, most Muslims faced this choice after the

Revolt of the Brotherhoods

The Revolt of the Brotherhoods ( ca, Revolta de les Germanies, es, Rebelión de las Germanías) was a revolt by artisan guilds ('' Germanies'') against the government of King Charles V in the Kingdom of Valencia, part of the Crown of Aragon. ...

(1519–1523). It is important to note that the enforcement of the expulsion of the moriscos was enforced really unevenly, especially in the lands of the interior and the north, where the coexistence had lasted for over five centuries and moriscos were protected by the population, and orders were partially or completely ignored.

The

War of the Alpujarras (1568–71), a general Muslim/Morisco uprising in Granada that expected to aid Ottoman disembarkation in the peninsula, ended in a forced dispersal of about half of the region's Moriscos throughout Castile and Andalusia as well as increased suspicions by Spanish authorities against this community.

Many Moriscos were suspected of practising Islam in secret, and the jealousy with which they guarded the privacy of their domestic life prevented the verification of this suspicion. Initially, they were not severely persecuted by the Inquisition, experiencing instead a policy of evangelization a policy not followed with those ''conversos'' who were suspected of being crypto-Jews. There were various reasons for this. In the kingdoms of Valencia and Aragon, a large number of the Moriscos were under the jurisdiction of the nobility, and persecution would have been viewed as a frontal assault on the economic interests of this powerful social class. Most importantly, the moriscos had integrated into the Spanish society significantly better than the Jews, intermarrying with the population often, and were not seen as a foreign element, especially in rural areas. Still, fears ran high among the population that the Moriscos were traitorous, especially in Granada. The coast was regularly raided by

Barbary pirate

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe as the ...

s backed by Spain's enemy, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and the Moriscos were suspected of aiding them.

In the second half of the century, late in the reign of Philip II, conditions worsened between

Old Christians

Old Christian ( es, cristiano viejo, pt, cristão-velho, ca, cristià vell) was a social and law-effective category used in the Iberian Peninsula from the late 15th and early 16th century onwards, to distinguish Portuguese and Spanish people att ...

and Moriscos. The

Morisco Revolt

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

in Granada in 1568–1570 was harshly suppressed, and the Inquisition intensified its attention on the Moriscos. From 1570 Morisco cases became predominant in the tribunals of

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributa ...

, Valencia and Granada; in the tribunal of Granada, between 1560 and 1571, 82% of those accused were Moriscos, who were a vast majority of the Kingdom's population at the time. Still, the Moriscos did not experience the same harshness as judaizing ''conversos'' and Protestants, and the number of capital punishments was proportionally less.

In 1609, King

Philip III, upon the advice of his financial adviser the

Duke of Lerma

Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, 5th Marquess of Denia, 1st Count of Ampudia (1552/1553 – 17 May 1625), was a favourite of Philip III of Spain, the first of the ''validos'' ('most worthy') through whom the later H ...

and Archbishop of Valencia

Juan de Ribera

Juan de Ribera (Seville, Spain, 20 March 1532 – Valencia, 6 January 1611) was an influential figure in 16th and 17th century Spain. Ribera held appointments as Archbishop and Viceroy of Valencia, Latin Patriarchate of Antioch, Commander in ...

, decreed the

Expulsion of the Moriscos

The Expulsion of the Moriscos ( es, Expulsión de los moriscos) was decreed by King Philip III of Spain on April 9, 1609. The Moriscos were descendants of Spain's Muslim population who had been forced to convert to Christianity. Since the Spani ...

. Hundreds of thousands of Moriscos were expelled. This was further fueled by the religious intolerance of Archbishop Ribera who quoted the Old Testament texts ordering the enemies of God to be slain without mercy and setting forth the duties of kings to extirpate them. The edict required: 'The

Moriscos

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

to depart, under the pain of death and confiscation, without trial or sentence... to take with them no money, bullion, jewels or bills of exchange.... just what they could carry.' Although initial estimates of the number expelled such as those of Henri Lapeyre reach 300,000 Moriscos (or 4% of the total Spanish population), the extent and severity of the expulsion in much of Spain has been increasingly challenged by modern historians such as Trevor J. Dadson.

[Trevor J. Dadson]

''The Assimilation of Spain's Moriscos: Fiction or Reality?''

. Journal of Levantine Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, Winter 2011, pp. 11–30 Nevertheless, the eastern region of Valencia, where ethnic tensions were high, was particularly affected by the expulsion, suffering economic collapse and depopulation of much of its territory.

Of those permanently expelled, the majority finally settled in the Maghreb or the Barbary coast. Those who avoided expulsion or who managed to return were gradually absorbed by the dominant culture.

The Inquisition pursued some trials against Moriscos who remained or returned after expulsion: at the height of the Inquisition, cases against Moriscos are estimated to have constituted less than 10 percent of those judged by the Inquisition. Upon the coronation of

Philip IV in 1621, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on remaining Moriscos and returnees. In September 1628 the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion." The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. By the end of the 18th century, the indigenous practice of Islam is considered to have been effectively extinguished in Spain.

Christian heretics

The Spanish Inquisition had jurisdiction only over Christians. Therefore, only those who self-identified as Christians could be investigated and trialed by it. Those in the group of "heretics" were all subject to investigation. All forms of heretic Christianity (Protestants, Orthodox, blaspheming Catholics, etc.) were considered under its jurisdiction.

Protestants and Anglicans

Despite popular myths about the Spanish Inquisition relating to Protestants, it dealt with very few cases involving actual Protestants, as there were so few in Spain. The

Inquisition of the Netherlands is here not considered part of the Spanish Inquisition. Lutheran was a portmanteau accusation used by the Inquisition to act against all those who acted in a way that was offensive to the church. The first of the trials against those labeled by the Inquisition as "Lutheran" were those against the sect of

mystics

A mystic is a person who practices mysticism, or a reference to a mystery, mystic craft, first hand-experience or the occult.

Mystic may also refer to:

Places United States

* Mistick, an old name for parts of Malden and Medford, Massachusetts

...

known as the "

Alumbrados" of

Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Mexico, while the Guadalaj ...

and

Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

. The trials were long and ended with prison sentences of differing lengths, though none of the sect were executed. Nevertheless, the subject of the "Alumbrados" put the Inquisition on the trail of many intellectuals and clerics who, interested in

Erasmian ideas, had strayed from orthodoxy. This is striking because both Charles I and

Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

were confessed admirers of

Erasmus. The humanist

Juan de Valdés

Juan de Valdés (c.1490 – August 1541) was a Spanish religious writer and Catholic reformer.

He was the younger of twin sons of Fernando de Valdés, hereditary ''regidor'' of Cuenca in Castile, where Valdés was born. He has been confuse ...

, fled to Italy to escape anti-Erasmian factions that came to power in the court,

and the preacher,

Juan de Ávila spent close to a year in prison after he was questioned about his prayer practices.

The first trials against

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

groups, as such, took place between 1558 and 1562, at the beginning of the reign of Philip II, against two communities of Protestants from the cities of Valladolid and Seville, numbering about 120. The trials signaled a notable intensification of the Inquisition's activities. A number of ''

autos-da-fé'' were held, some of them presided over by members of the royal family, and around 100 executions took place. The ''autos-da-fé'' of the mid-century virtually put an end to Spanish Protestantism, which was, throughout, a small phenomenon to begin with.

After 1562, though the trials continued, the repression was much reduced. About 200 Spaniards were accused of being Protestants in the last decades of the 16th century.

Most of them were in no sense Protestants ... Irreligious sentiments, drunken mockery, anticlerical expressions, were all captiously classified by the inquisitors (or by those who denounced the cases) as "Lutheran." Disrespect to church images, and eating meat on forbidden days, were taken as signs of heresy...

It is estimated that a dozen Spaniards were burned alive.