Southern Song on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by

After usurping the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty,

After usurping the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty,  The Song dynasty managed to win several military victories over the Tanguts in the early 11th century, culminating in a campaign led by the polymath scientist, general, and statesman

The Song dynasty managed to win several military victories over the Tanguts in the early 11th century, culminating in a campaign led by the polymath scientist, general, and statesman  During the 11th century, political rivalries divided members of the court due to the ministers' differing approaches, opinions, and policies regarding the handling of the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist

During the 11th century, political rivalries divided members of the court due to the ministers' differing approaches, opinions, and policies regarding the handling of the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist

Although weakened and pushed south beyond the Huai River, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster its strong economy and defend itself against the Jin dynasty. It had able military officers such as

Although weakened and pushed south beyond the Huai River, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster its strong economy and defend itself against the Jin dynasty. It had able military officers such as

The Song dynasty was an era of administrative sophistication and complex social organization. Some of the largest cities in the world were found in China during this period (Kaifeng and Hangzhou had populations of over a million). People enjoyed various social clubs and entertainment in the cities, and there were many schools and temples to provide the people with education and religious services. The Song government supported

The Song dynasty was an era of administrative sophistication and complex social organization. Some of the largest cities in the world were found in China during this period (Kaifeng and Hangzhou had populations of over a million). People enjoyed various social clubs and entertainment in the cities, and there were many schools and temples to provide the people with education and religious services. The Song government supported  Although women were on a lower social tier than men (according to Confucian ethics), they enjoyed many social and legal privileges and wielded considerable power at home and in their own small businesses. As Song society became more and more prosperous and parents on the bride's side of the family provided larger dowries for her marriage, women naturally gained many new legal rights in ownership of property. Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers, or a surviving mother without sons, could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property. There were many notable and well-educated women, and it was a common practice for women to educate their sons during their earliest youth. The mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo taught him essentials of military strategy. There were also exceptional women writers and poets, such as Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), who became famous even in her lifetime.

Although women were on a lower social tier than men (according to Confucian ethics), they enjoyed many social and legal privileges and wielded considerable power at home and in their own small businesses. As Song society became more and more prosperous and parents on the bride's side of the family provided larger dowries for her marriage, women naturally gained many new legal rights in ownership of property. Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers, or a surviving mother without sons, could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property. There were many notable and well-educated women, and it was a common practice for women to educate their sons during their earliest youth. The mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo taught him essentials of military strategy. There were also exceptional women writers and poets, such as Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), who became famous even in her lifetime.

Due to Song's enormous population growth and the body of its appointed scholar-officials being accepted in limited numbers (about 20,000 active officials during the Song period), the larger scholarly gentry class would now take over grassroots affairs on the vast local level. Excluding the scholar-officials in office, this elite social class consisted of exam candidates, examination degree-holders not yet assigned to an official post, local tutors, and retired officials. These learned men, degree-holders, and local elites supervised local affairs and sponsored necessary facilities of local communities; any local magistrate appointed to his office by the government relied upon the cooperation of the few or many local gentry in the area. For example, the Song government—excluding the educational-reformist government under Emperor Huizong—spared little amount of state revenue to maintain

Due to Song's enormous population growth and the body of its appointed scholar-officials being accepted in limited numbers (about 20,000 active officials during the Song period), the larger scholarly gentry class would now take over grassroots affairs on the vast local level. Excluding the scholar-officials in office, this elite social class consisted of exam candidates, examination degree-holders not yet assigned to an official post, local tutors, and retired officials. These learned men, degree-holders, and local elites supervised local affairs and sponsored necessary facilities of local communities; any local magistrate appointed to his office by the government relied upon the cooperation of the few or many local gentry in the area. For example, the Song government—excluding the educational-reformist government under Emperor Huizong—spared little amount of state revenue to maintain

Although the scholar-officials viewed military soldiers as lower members in the hierarchic social order, a person could gain status and prestige in society by becoming a high-ranking military officer with a record of victorious battles. At its height, the Song military had one million soldiers divided into

Although the scholar-officials viewed military soldiers as lower members in the hierarchic social order, a person could gain status and prestige in society by becoming a high-ranking military officer with a record of victorious battles. At its height, the Song military had one million soldiers divided into  Military strategy and military training were treated as sciences that could be studied and perfected; soldiers were tested in their skills of using weaponry and in their athletic ability. The troops were trained to follow signal standards to advance at the waving of banners and to halt at the sound of bells and drums.

The Song navy was of great importance during the consolidation of the empire in the 10th century; during the war against the

Military strategy and military training were treated as sciences that could be studied and perfected; soldiers were tested in their skills of using weaponry and in their athletic ability. The troops were trained to follow signal standards to advance at the waving of banners and to halt at the sound of bells and drums.

The Song navy was of great importance during the consolidation of the empire in the 10th century; during the war against the

In

In

The main food staples in the diet of the lower classes remained rice,

The main food staples in the diet of the lower classes remained rice,

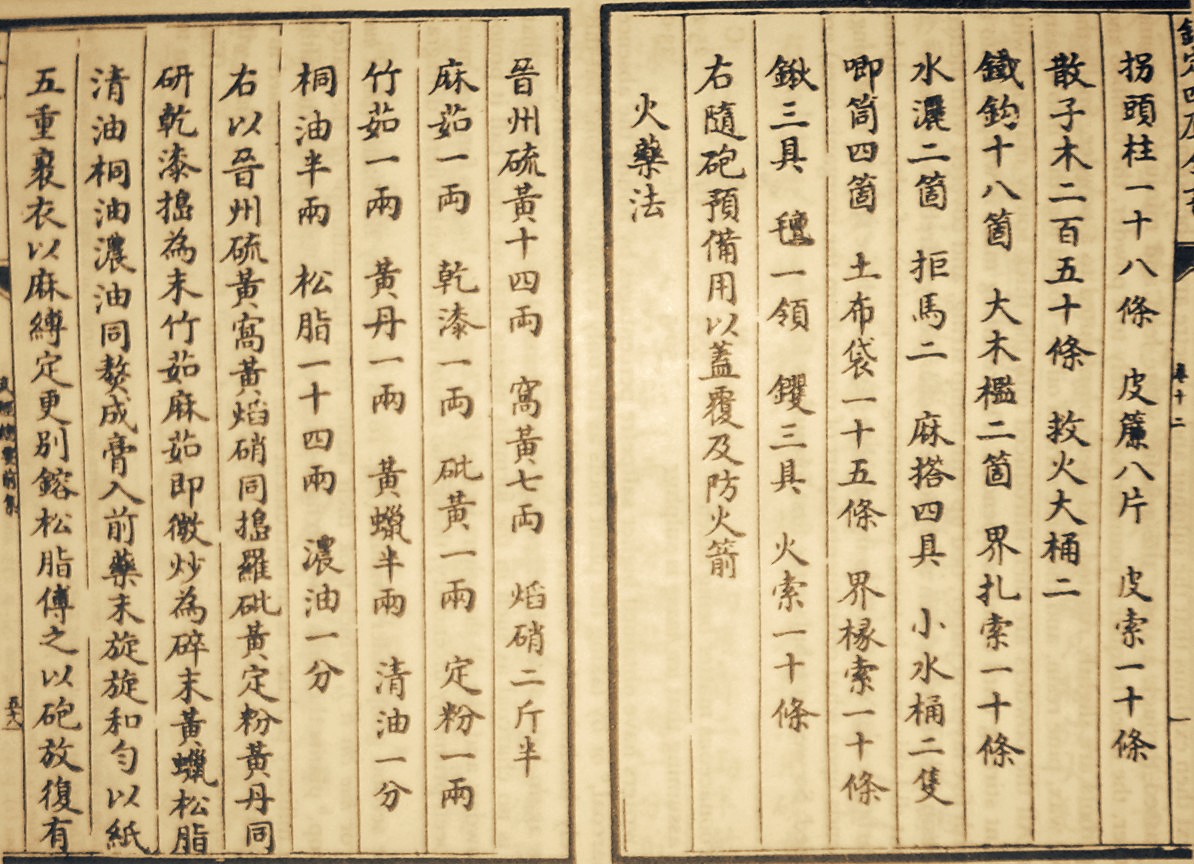

Advancements in weapons technology enhanced by gunpowder, including the evolution of the early

Advancements in weapons technology enhanced by gunpowder, including the evolution of the early

There were many notable improvements to

There were many notable improvements to

There were other considerable advancements in

There were other considerable advancements in

In addition to the Song gentry's antiquarian pursuits of art collecting, scholar-officials during the Song became highly interested in retrieving ancient relics from

In addition to the Song gentry's antiquarian pursuits of art collecting, scholar-officials during the Song became highly interested in retrieving ancient relics from

Song dynasty at China Heritage Quarterly

Song dynasty art with video commentary

The Newly Compiled Overall Geographical Survey

{{Featured article 10th-century establishments in China . . 1279 disestablishments in Asia 13th-century disestablishments in China 960 establishments Dynasties in Chinese history Former countries in Chinese history Medieval Asia States and territories disestablished in 1279 States and territories established in the 960s

Emperor Taizu of Song

Emperor Taizu of Song (21 March 927 – 14 November 976), personal name Zhao Kuangyin, courtesy name Yuanlang, was the founder and first emperor of the Song dynasty of China. He reigned from 960 until his death in 976. Formerly a distinguish ...

following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou

Zhou, known as the Later Zhou (; ) in historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty and the last of the Five Dynasties that controlled most of northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Founded by Guo Wei ( ...

. The Song conquered the rest of the Ten Kingdoms, ending the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (), from 907 to 979, was an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century Imperial China. Five dynastic states quickly succeeded one another in the Central Plain, and more than a dozen conc ...

. The Song often came into conflict with the contemporaneous Liao, Western Xia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

and Jin dynasties in northern China

Northern China () and Southern China () are two approximate regions within China. The exact boundary between these two regions is not precisely defined and only serve to depict where there appears to be regional differences between the climate ...

. After retreating to southern China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

, the Song was eventually conquered by the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

-led Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

.

The dynasty is divided into two periods: Northern Song and Southern Song. During the Northern Song (; 960–1127), the capital was in the northern city of Bianjing

Kaifeng () is a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. It is one of the Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and is best known for having been the Chinese capital during the Nor ...

(now Kaifeng

Kaifeng () is a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. It is one of the Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and is best known for having been the Chinese capital during the Nort ...

) and the dynasty controlled most of what is now Eastern China. The Southern Song

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(; 1127–1279) refers to the period after the Song lost control of its northern half to the Jurchen Jurchen may refer to:

* Jurchen people, Tungusic people who inhabited the region of Manchuria until the 17th century

** Haixi Jurchens, a grouping of the Jurchens as identified by the Chinese of the Ming Dynasty

** Jianzhou Jurchens, a grouping of ...

-led Jin dynasty in the Jin–Song Wars

The Jin–Song Wars were a series of conflicts between the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and the Han-led Song dynasty (960–1279). In 1115, Jurchen tribes rebelled against their overlords, the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (916–1125), ...

. At that time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

and established its capital at Lin'an (now Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

). Although the Song dynasty had lost control of the traditional Chinese heartlands around the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

, the Southern Song Empire contained a large population and productive agricultural land, sustaining a robust economy. In 1234, the Jin dynasty was conquered by the Mongols, who took control of northern China, maintaining uneasy relations with the Southern Song. Möngke Khan

Möngke ( mn, ' / Мөнх '; ; 11 January 1209 – 11 August 1259) was the fourth khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire, ruling from 1 July 1251, to 11 August 1259. He was the first Khagan from the Toluid line, and made significant reform ...

, the fourth Great Khan

Khagan or Qaghan (Mongolian:; or ''Khagan''; otk, 𐰴𐰍𐰣 ), or , tr, Kağan or ; ug, قاغان, Qaghan, Mongolian Script: ; or ; fa, خاقان ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan ...

of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

, died in 1259 while besieging the mountain castle Diaoyucheng

The Diaoyucheng (), or Diaoyu Fortress, is a fortress located on the Diaoyu Mountain in Heyang Town, Hechuan District, Chongqing. It is known for its resistance to the Mongol armies in the latter half of the Song dynasty.

History

The death ...

, Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Co ...

. His younger brother Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

was proclaimed the new Great Khan and in 1271 founded the Yuan dynasty. After two decades of sporadic warfare, Kublai Khan's armies conquered the Song dynasty in 1279 after defeating the Southern Song in the Battle of Yamen

The naval Battle of Yamen () (also known as the Naval Battle of Mount Ya; ) took place on 19 March 1279 and is considered to be the last stand of the Song dynasty against the invading Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. Although outnumbered 10:1, the Yua ...

, and reunited China under the Yuan dynasty.

Technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scien ...

, science, philosophy, mathematics, and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

flourished during the Song era. The Song dynasty was the first in world history to issue banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s or true paper money and the first Chinese government to establish a permanent standing navy. This dynasty saw the first recorded chemical formula

In chemistry, a chemical formula is a way of presenting information about the chemical proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound or molecule, using chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, ...

of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, the invention of gunpowder weapons such as fire arrow

Fire arrows were one of the earliest forms of weaponized gunpowder, being used from the 9th century onward. Not to be confused with earlier incendiary arrow projectiles, the fire arrow was a gunpowder weapon which receives its name from the tra ...

s, bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

s, and the fire lance

The fire lance () was a gunpowder weapon and the ancestor of modern firearms. It first appeared in 10th–12th century China and was used to great effect during the Jin-Song Wars. It began as a small pyrotechnic device attached to a polearm weap ...

. It also saw the first discernment of true north

True north (also called geodetic north or geographic north) is the direction along Earth's surface towards the geographic North Pole or True North Pole.

Geodetic north differs from ''magnetic'' north (the direction a compass points toward t ...

using a compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

, first recorded description of the pound lock, and improved designs of astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition ...

s. Economically, the Song dynasty was unparalleled with a gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is of ...

three times larger than that of Europe during the 12th century. China's population doubled in size between the 10th and 11th centuries. This growth was made possible by expanded rice cultivation

The history of rice cultivation is an interdisciplinary subject that studies archaeological and documentary evidence to explain how rice was first domesticated and cultivated by humans, the spread of cultivation to different regions of the planet, ...

, use of early-ripening rice from Southeast and South Asia, and production of widespread food surpluses. The Northern Song census recorded 20 million households, double of the Han and Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) ...

dynasties. It is estimated that the Northern Song had a population of 90 million people, and 200 million by the time of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

. This dramatic increase of population fomented an economic revolution in pre-modern China.

The expansion of the population, growth of cities, and emergence of a national economy led to the gradual withdrawal of the central government from direct involvement in economic affairs. The lower gentry assumed a larger role in local administration and affairs. Social life during the Song was vibrant. Citizens gathered to view and trade precious artworks, the populace intermingled at public festivals and private clubs, and cities had lively entertainment quarters. The spread of literature and knowledge was enhanced by the rapid expansion of woodblock printing

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is crea ...

and the 11th-century invention of movable-type printing. Philosophers such as Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi (; ; October 18, 1130 – April 23, 1200), formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He con ...

reinvigorated Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a Religious Confucianism, religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, ...

with new commentary, infused with Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

ideals, and emphasized a new organization of classic texts that established the doctrine of Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism (, often shortened to ''lǐxué'' 理學, literally "School of Principle") is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, and originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) ...

. Although civil service examinations had existed since the Sui dynasty

The Sui dynasty (, ) was a short-lived imperial dynasty of China that lasted from 581 to 618. The Sui unified the Northern and Southern dynasties, thus ending the long period of division following the fall of the Western Jin dynasty, and la ...

, they became much more prominent in the Song period. Officials gaining power through imperial examination

The imperial examination (; lit. "subject recommendation") refers to a civil-service examination system in Imperial China, administered for the purpose of selecting candidates for the state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureaucrats by ...

led to a shift from a military-aristocratic elite to a scholar-bureaucratic elite.

History

Northern Song, 960–1127

After usurping the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty,

After usurping the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty, Emperor Taizu of Song

Emperor Taizu of Song (21 March 927 – 14 November 976), personal name Zhao Kuangyin, courtesy name Yuanlang, was the founder and first emperor of the Song dynasty of China. He reigned from 960 until his death in 976. Formerly a distinguish ...

( 960–976) spent sixteen years conquering the rest of China, reuniting much of the territory that had once belonged to the Han and Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) ...

empires and ending the upheaval of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (), from 907 to 979, was an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century Imperial China. Five dynastic states quickly succeeded one another in the Central Plain, and more than a dozen conc ...

. In Kaifeng

Kaifeng () is a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. It is one of the Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and is best known for having been the Chinese capital during the Nort ...

, he established a strong central government over the empire. The establishment of this capital marked the start of the Northern Song period. He ensured administrative stability by promoting the civil service examination

Civil service examinations are examinations implemented in various countries for recruitment and admission to the civil service. They are intended as a method to achieve an effective, rational public administration on a merit system for recruitin ...

system of drafting state bureaucrat

A bureaucrat is a member of a bureaucracy and can compose the administration of any organization of any size, although the term usually connotes someone within an institution of government.

The term ''bureaucrat'' derives from "bureaucracy", w ...

s by skill and merit (instead of aristocrat

The aristocracy is historically associated with "hereditary" or "ruling" social class. In many states, the aristocracy included the upper class of people (aristocrats) with hereditary rank and titles. In some, such as ancient Greece, ancient R ...

ic or military position) and promoted projects that ensured efficiency in communication throughout the empire. In one such project, cartographers

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

created detailed maps of each province and city that were then collected in a large atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geogra ...

. Emperor Taizu also promoted groundbreaking scientific and technological innovations by supporting works like the astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxi ...

clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another buildi ...

designed and built by the engineer Zhang Sixun.

The Song court maintained diplomatic relations with Chola India, the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a ...

of Egypt, Srivijaya

Srivijaya ( id, Sriwijaya) was a Buddhist thalassocratic empire based on the island of Sumatra (in modern-day Indonesia), which influenced much of Southeast Asia. Srivijaya was an important centre for the expansion of Buddhism from the 7th ...

, the Kara-Khanid Khanate

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (; ), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids or the Afrasiabids (), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek K ...

in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

, the Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificat ...

kingdom in Korea, and other countries that were also trade partners with Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. Chinese records even mention an embassy from the ruler of "Fu lin" (拂菻, i.e. the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

), Michael VII Doukas

Michael VII Doukas or Ducas ( gr, Μιχαήλ Δούκας), nicknamed Parapinakes ( gr, Παραπινάκης, lit. "minus a quarter", with reference to the devaluation of the Byzantine currency under his rule), was the senior Byzantine e ...

, and its arrival in 1081. However, China's closest neighbouring states had the greatest impact on its domestic and foreign policy. From its inception under Taizu, the Song dynasty alternated between warfare and diplomacy with the ethnic Khitans

The Khitan people (Khitan small script: ; ) were a historical nomadic people from Northeast Asia who, from the 4th century, inhabited an area corresponding to parts of modern Mongolia, Northeast China and the Russian Far East.

As a people desce ...

of the Liao dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 916 and 1125, ruled by the Yelü ...

in the northeast and with the Tanguts

The Tangut people ( Tangut: , ''mjɨ nja̱'' or , ''mji dzjwo''; ; ; mn, Тангуд) were a Tibeto-Burman tribal union that founded and inhabited the Western Xia dynasty. The group initially lived under Tuyuhun authority, but later submitted ...

of the Western Xia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

in the northwest. The Song dynasty used military force in an attempt to quell the Liao dynasty and to recapture the Sixteen Prefectures

The Sixteen Prefectures () comprise a historical region in northern China along the Great Wall in present-day Beijing, Tianjin, and northern Hebei and Shanxi.

Name

It is more specifically called the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan and Yun or the Si ...

, a territory under Khitan control since 938 that was traditionally considered to be part of China proper

China proper, Inner China, or the Eighteen Provinces is a term used by some Western writers in reference to the "core" regions of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China. This term is used to express a distinction between the "core" regions pop ...

(Most parts of today's Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

and Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popu ...

). Song forces were repulsed by the Liao forces, who engaged in aggressive yearly campaigns into Northern Song territory until 1005, when the signing of the Shanyuan Treaty ended these northern border clashes. The Song were forced to provide tribute to the Khitans, although this did little damage to the Song economy since the Khitans were economically dependent upon importing massive amounts of goods from the Song. More significantly, the Song state recognized the Liao state as its diplomatic equal. The Song created an extensive defensive forest along the Song-Liao border to thwart potential Khitan cavalry attacks.

The Song dynasty managed to win several military victories over the Tanguts in the early 11th century, culminating in a campaign led by the polymath scientist, general, and statesman

The Song dynasty managed to win several military victories over the Tanguts in the early 11th century, culminating in a campaign led by the polymath scientist, general, and statesman Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031–1095). However, this campaign was ultimately a failure due to a rival military officer of Shen disobeying direct orders, and the territory gained from the Western Xia was eventually lost. The Song fought against the Vietnamese kingdom of Đại Việt

Đại Việt (, ; literally Great Việt), often known as Annam ( vi, An Nam, Chữ Hán: 安南), was a monarchy in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century, centered around the region of present-day H ...

twice, the first conflict in 981

Year 981 ( CMLXXXI) was a common year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

Births

* Abu'l-Qasim al-Husayn ibn Ali al-Maghribi, Arab statesman (d. 1027)

* Giovanni Orseolo, Venetian ...

and later a significant war from 1075 to 1077 over a border dispute and the Song's severing of commercial relations with Đại Việt. After the Vietnamese forces inflicted heavy damages in a raid on Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

, the Song commander Guo Kui (1022–1088) penetrated as far as Thăng Long (modern Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi i ...

). Heavy losses on both sides prompted the Vietnamese commander Thường Kiệt (1019–1105) to make peace overtures, allowing both sides to withdraw from the war effort; captured territories held by both Song and Vietnamese were mutually exchanged in 1082, along with prisoners of war.

During the 11th century, political rivalries divided members of the court due to the ministers' differing approaches, opinions, and policies regarding the handling of the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist

During the 11th century, political rivalries divided members of the court due to the ministers' differing approaches, opinions, and policies regarding the handling of the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, Fan Zhongyan

Fan Zhongyan (5 September 989 – 19 June 1052) from Wu County of Suzhou ( Jiangsu Province, China), courtesy name Xiwen (), ratified as the Duke of Wenzheng () posthumously, and conferred as Duke of Chu () posthumously, was a Chinese poet, p ...

(989–1052), was the first to receive a heated political backlash when he attempted to institute the Qingli Reforms, which included measures such as improving the recruitment system of officials, increasing the salaries for minor officials, and establishing sponsorship programs to allow a wider range of people to be well educated and eligible for state service.

After Fan was forced to step down from his office, Wang Anshi

Wang Anshi ; ; December 8, 1021 – May 21, 1086), courtesy name Jiefu (), was a Chinese economist, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. He served as chancellor and attempted major and controversial socioeconomic reforms ...

(1021–1086) became Chancellor of the imperial court. With the backing of Emperor Shenzong (1067–1085), Wang Anshi severely criticized the educational system and state bureaucracy. Seeking to resolve what he saw as state corruption and negligence, Wang implemented a series of reforms called the New Policies. These involved land value tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land (economics), land without regard to buildings, personal property and other land improvement, improvements. It is also known as a location value tax, a point valuation tax, a site valuation ta ...

reform, the establishment of several government monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, the support of local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s, and the creation of higher standards for the Imperial examination to make it more practical for men skilled in statecraft to pass.

The reforms created political factions in the court. Wang Anshi's "New Policies Group" (''Xin Fa''), also known as the "Reformers", were opposed by the ministers in the "Conservative" faction led by the historian and Chancellor Sima Guang

Sima Guang (17 November 1019 – 11 October 1086), courtesy name Junshi, was a Chinese historian, politician, and writer. He was a high-ranking Song dynasty scholar-official who authored the monumental history book ''Zizhi Tongjian''. Sima was ...

(1019–1086). As one faction supplanted another in the majority position of the court ministers, it would demote rival officials and exile them to govern remote frontier regions of the empire. One of the prominent victims of the political rivalry, the famous poet and statesman Su Shi

Su Shi (; 8 January 1037 – 24 August 1101), courtesy name Zizhan (), art name Dongpo (), was a Chinese calligrapher, essayist, gastronomer, pharmacologist, poet, politician, and travel writer during the Song dynasty. A major personality of ...

(1037–1101), was jailed and eventually exiled for criticizing Wang's reforms.

The continual alternation between reform and conservatism had effectively weakened the dynasty. This decline can also be attributed to Cai Jing

Cai Jing (1047–1126), courtesy name Yuanchang (), was a Chinese calligrapher and politician who lived during the Northern Song dynasty of China. He is also fictionalised as one of the primary antagonists in '' Water Margin'', one of the Four ...

(1047–1126), who was appointed by Emperor Zhezong

Emperor Zhezong of Song (4 January 1077 – 23 February 1100), personal name Zhao Xu, was the seventh emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Yong but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after his coronation. He reig ...

(1085–1100) and who remained in power until 1125. He revived the New Policies and pursued political opponents, tolerated corruption and encouraged Emperor Huizong (1100–1126) to neglect his duties to focus on artistic pursuits. Later, a peasant rebellion broke out in Zhejiang and Fujian, headed by Fang La

Fang La (; died 1121) was a Chinese rebel leader who led an uprising against the Song dynasty. In the classical novel '' Water Margin'', he is fictionalised as one of the primary antagonists and nemeses of the 108 Stars of Destiny. He is someti ...

in 1120. The rebellion may have been caused by an increasing tax burden, the concentration of landownership and oppressive government measures.

While the central Song court remained politically divided and focused upon its internal affairs, alarming new events to the north in the Liao state finally came to its attention. The Jurchen Jurchen may refer to:

* Jurchen people, Tungusic people who inhabited the region of Manchuria until the 17th century

** Haixi Jurchens, a grouping of the Jurchens as identified by the Chinese of the Ming Dynasty

** Jianzhou Jurchens, a grouping of ...

, a subject tribe of the Liao, rebelled against them and formed their own state, the Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jin dynasty (,

; ) or Jin State (; Jurchen: Anchun Gurun), officially known as the Great Jin (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 1115 and 1234. Its name is sometimes written as Kin, Jurchen Jin, Jinn, or Chin

in ...

. The Song official Tong Guan (1054–1126) advised Emperor Huizong to form an alliance with the Jurchens, and the joint military campaign under this Alliance Conducted at Sea

The Alliance Conducted at Sea () was a political alliance in Chinese history between the Song and Jin dynasties in the early 12th century against the Liao dynasty. The alliance was negotiated from 1115 to 1123 by envoys who crossed the Bohai Sea.. ...

toppled and completely conquered the Liao dynasty by 1125. During the joint attack, the Song's northern expedition army removed the defensive forest along the Song-Liao border.

However, the poor performance and military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jurchens, who immediately broke the alliance, beginning the Jin–Song Wars

The Jin–Song Wars were a series of conflicts between the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and the Han-led Song dynasty (960–1279). In 1115, Jurchen tribes rebelled against their overlords, the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (916–1125), ...

of 1125 and 1127. Because of the removal of the previous defensive forest, the Jin army marched quickly across the North China Plain to Kaifeng. In the Jingkang Incident during the latter invasion, the Jurchens captured not only the capital, but the retired Emperor Huizong, his successor Emperor Qinzong

Emperor Qinzong of Song (23 May 1100 – 14 June 1161), personal name Zhao Huan, was the ninth emperor of the Song dynasty of China and the last emperor of the Northern Song dynasty.

Emperor Qinzong was the eldest son and heir apparent of Empe ...

, and most of the Imperial court.

The remaining Song forces regrouped under the self-proclaimed Emperor Gaozong of Song

Emperor Gaozong of Song (12 June 1107 – 9 November 1187), personal name Zhao Gou, courtesy name Deji, was the tenth emperor of the Song dynasty and the first of the Southern Song period, ruling between 1127 and 1162 and retaining power as re ...

(1127–1162) and withdrew south of the Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

to establish a new capital at Lin'an (modern Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

). The Jurchen conquest of North China

North China, or Huabei () is a geographical region of China, consisting of the provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Part of the larger region of Northern China (''Beifang''), it lies north of the Qinling–Hu ...

and shift of capitals from Kaifeng to Lin'an was the dividing line between the Northern and Southern Song

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

dynasties.

After their fall to the Jin, the Song lost control of North China. Now occupying what has been traditionally known as "China Proper," the Jin regarded themselves the rightful rulers of China. The Jin later chose earth as their dynastic element and yellow as their royal color. According to the theory of the Five Elements (wuxing), the earth element follows the fire, the dynastic element of the Song, in the sequence of elemental creation. Therefore, their ideological move showed that the Jin considered Song reign in China complete, with the Jin replacing the Song as the rightful rulers of China Proper.

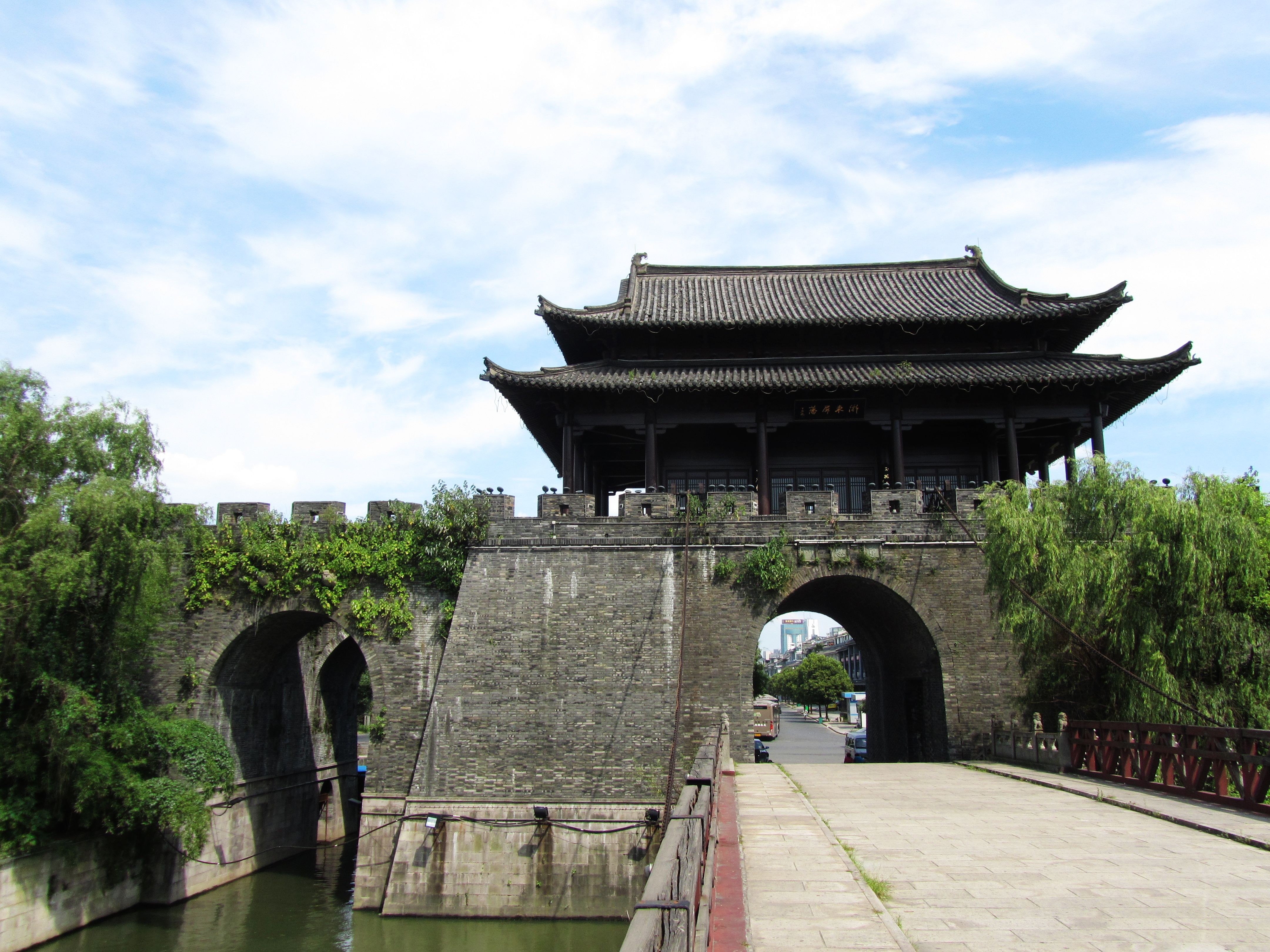

Southern Song, 1127–1279

Although weakened and pushed south beyond the Huai River, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster its strong economy and defend itself against the Jin dynasty. It had able military officers such as

Although weakened and pushed south beyond the Huai River, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster its strong economy and defend itself against the Jin dynasty. It had able military officers such as Yue Fei

Yue Fei ( zh, t=岳飛; March 24, 1103 – January 28, 1142), courtesy name Pengju (), was a Chinese military general who lived during the Southern Song dynasty and a national hero of China, known for leading Southern Song forces in the wa ...

and Han Shizhong

Han Shizhong () (1089–1151) was a Chinese military general, poet, and politician of the late Northern Song Dynasty and the early Southern Song Dynasty. He dedicated his whole life to serving the Song Dynasty, and performed many legendary dee ...

. The government sponsored massive shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to bef ...

and harbor

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

improvement projects, and the construction of beacon

A beacon is an intentionally conspicuous device designed to attract attention to a specific location. A common example is the lighthouse, which draws attention to a fixed point that can be used to navigate around obstacles or into port. More mode ...

s and seaport warehouse

A warehouse is a building for storing goods. Warehouses are used by manufacturers, importers, exporters, wholesalers, transport businesses, customs, etc. They are usually large plain buildings in industrial parks on the outskirts of citie ...

s to support maritime trade abroad, including at the major international seaport

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as ...

s, such as Quanzhou

Quanzhou, alternatively known as Chinchew, is a prefecture-level port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian, China. It is Fujian's largest metropolitan region, with an area of and a popul ...

, Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

, and Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong' ...

, that were sustaining China's commerce.

To protect and support the multitude of ships sailing for maritime interests into the waters of the East China Sea

The East China Sea is an arm of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. It covers an area of roughly . The sea’s northern extension between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula is the Yellow Sea, separated ...

and Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour ter ...

(to Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

), Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

, and the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

, it was necessary to establish an official standing navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

. The Song dynasty therefore established China's first permanent navy in 1132, with a headquarters at Dinghai. With a permanent navy, the Song were prepared to face the naval forces of the Jin on the Yangtze River in 1161, in the Battle of Tangdao and the Battle of Caishi. During these battles the Song navy employed swift paddle wheel driven naval vessels armed with traction trebuchet catapults aboard the decks that launched gunpowder bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

s. Although the Jin forces commanded by Wanyan Liang (the Prince of Hailing) boasted 70,000 men on 600 warships, and the Song forces only 3,000 men on 120 warships, the Song dynasty forces were victorious in both battles due to the destructive power of the bombs and the rapid assaults by paddlewheel ships. The strength of the navy was heavily emphasized following these victories. A century after the navy was founded it had grown in size to 52,000 fighting marines.

The Song government confiscated portions of land owned by the landed gentry in order to raise revenue for these projects, an act which caused dissension and loss of loyalty amongst leading members of Song society but did not stop the Song's defensive preparations. Financial matters were made worse by the fact that many wealthy, land-owning families—some of which had officials working for the government—used their social connections with those in office in order to obtain tax-exempt status.

Although the Song dynasty was able to hold back the Jin, a new foe came to power over the steppe, deserts, and plains north of the Jin dynasty. The Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, led by Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; ; xng, Temüjin, script=Latn; ., name=Temujin – August 25, 1227) was the founder and first Great Khan (Emperor) of the Mongol Empire, which became the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in history a ...

(r. 1206–1227), initially invaded the Jin dynasty in 1205 and 1209, engaging in large raids across its borders, and in 1211 an enormous Mongol army was assembled to invade the Jin. The Jin dynasty was forced to submit and pay tribute to the Mongols as vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

s; when the Jin suddenly moved their capital city from Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

to Kaifeng, the Mongols saw this as a revolt. Under the leadership of Ögedei Khan

Ögedei Khagan (also Ogodei;, Mongolian: ''Ögedei'', ''Ögüdei''; – 11 December 1241) was second khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire. The third son of Genghis Khan, he continued the expansion of the empire that his father had begun.

...

(r.1229–1241), both the Jin dynasty and Western Xia dynasty were conquered by Mongol forces in 1233/34.

The Mongols were allied with the Song, but this alliance was broken when the Song recaptured the former imperial capitals of Kaifeng, Luoyang

Luoyang is a city located in the confluence area of Luo River and Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the southeast, Nanyan ...

, and Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

at the collapse of the Jin dynasty. After the first Mongol invasion of Vietnam in 1258, Mongol general Uriyangkhadai attacked Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

from Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi i ...

as part of a coordinated Mongol attack in 1259 with armies attacking in Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

under Mongol leader Möngke Khan

Möngke ( mn, ' / Мөнх '; ; 11 January 1209 – 11 August 1259) was the fourth khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire, ruling from 1 July 1251, to 11 August 1259. He was the first Khagan from the Toluid line, and made significant reform ...

and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

and Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is a ...

. On August 11, 1259, Möngke Khan died during the siege of Diaoyu Castle

The siege of Diaoyucheng, alternatively the Siege of Diaoyu Castle, was a battle between the Southern Song dynasty and the Mongol Empire in 1259.History of Yuan vol.3 It occurred at the Diaoyu Fortress in modern-day Hechuan District, Chongqing, ...

in Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Co ...

.

Möngke's death and the ensuing succession crisis prompted Hulagu Khan

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Хүлэгү/ , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mongol ruler who conquered much of We ...

to pull the bulk of the Mongol forces out of the Middle East where they were poised to fight the Egyptian Mamluks

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16th ...

(who defeated the remaining Mongols at Ain Jalut). Although Hulagu was allied with Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

, his forces were unable to help in the assault against the Song, due to Hulagu's war with the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

.

Kublai continued the assault against the Song, gaining a temporary foothold on the southern banks of the Yangtze. By the winter of 1259, Uriyangkhadai's army fought its way north to meet Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

's army, which was besieging Ezhou

Ezhou () is a prefecture-level city in eastern Hubei Province, China. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 1,079,353, of which 695,697 lived in the core Echeng District. The Ezhou - Huanggang built-up (''or metro'') area was home ...

in Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

. Kublai made preparations to take Ezhou

Ezhou () is a prefecture-level city in eastern Hubei Province, China. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 1,079,353, of which 695,697 lived in the core Echeng District. The Ezhou - Huanggang built-up (''or metro'') area was home ...

, but a pending civil war with his brother Ariq Böke

Ariq Böke (after 1219–1266), the components of his name also spelled Arigh, Arik and Bukha, Buka ( mn, Аригбөх, Arigböh, ; ), was the seventh and youngest son of Tolui and a grandson of Genghis Khan. After the death of his brother the ...

—a rival claimant to the Mongol Khaganate—forced Kublai to move back north with the bulk of his forces. In Kublai's absence, the Song forces were ordered by Chancellor Jia Sidao to make an immediate assault and succeeded in pushing the Mongol forces back to the northern banks of the Yangtze. There were minor border skirmishes until 1265, when Kublai won a significant battle in Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

.

From 1268 to 1273, Kublai blockaded the Yangtze River with his navy and besieged Xiangyang, the last obstacle in his way to invading the rich Yangtze River basin. Kublai officially declared the creation of the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

in 1271. In 1275, a Song force of 130,000 troops under Chancellor Jia Sidao was defeated by Kublai's newly appointed commander-in-chief, general Bayan

Bayan may refer to:

Eduational Institutions

* Bayan Islamic Graduate School, Chicago, IL

Places

*Bayan-Aul, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan

*Bayan Mountain, an ancient mountain name for part of Tarbagatai Mountains at Kazakhstan in Qing Dynasty period

* ...

. By 1276, most of the Song territory had been captured by Yuan forces, including the capital Lin'an.

In the Battle of Yamen

The naval Battle of Yamen () (also known as the Naval Battle of Mount Ya; ) took place on 19 March 1279 and is considered to be the last stand of the Song dynasty against the invading Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. Although outnumbered 10:1, the Yua ...

on the Pearl River Delta

The Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region (PRD; ; pt, Delta do Rio das Pérolas (DRP)) is the low-lying area surrounding the Pearl River estuary, where the Pearl River flows into the South China Sea. Referred to as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Ma ...

in 1279, the Yuan army, led by the general Zhang Hongfan, finally crushed the Song resistance. The last remaining ruler, the 13-year-old emperor Zhao Bing

Zhao Bing (12 February 1272 – 19 March 1279), also known as Emperor Bing of Song or Bing, Emperor of Song (宋帝昺), was the 18th and last emperor of the Song dynasty of China, who ruled as a minor between 6 and 7 years of age.

He was a ...

, committed suicide, along with Prime Minister Lu Xiufu

Lu Xiufu (8 November 1236 – 19 March 1279), courtesy name Junshi (), was a Chinese statesman and military commander who lived in the final years of the Song dynasty. Originally from Yancheng (present-day Jianhu County) in Jiangsu Province, alo ...

and 1300 members of the royal clan. On Kublai's orders, carried out by his commander Bayan, the rest of the former imperial family of Song were unharmed; the deposed Emperor Gong was demoted, being given the title 'Duke of Ying', but was eventually exiled to Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

where he took up a monastic life. The former emperor would eventually be forced to commit suicide under the orders of Kublai's great-great grandson, Gegeen Khan, out of fear that Emperor Gong would stage a coup to restore his reign. Other members of the Song Imperial Family continued to live in the Yuan dynasty, including Zhao Mengfu

Zhao Mengfu (; courtesy name Zi'ang (子昂); pseudonyms Songxue (松雪, "Pine Snow"), Oubo (鷗波, "Gull Waves"), and Shuijing-gong Dao-ren (水精宮道人, "Master of the Water Spirits Palace"); 1254–1322), was a Chinese calligrapher, pa ...

and Zhao Yong.

Culture and society

social welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

programs including the establishment of retirement home

A retirement home – sometimes called an old people's home or old age home, although ''old people's home'' can also refer to a nursing home – is a multi-residence housing facility intended for the elderly. Typically, each person or couple in ...

s, public clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambulatory care clinic) is a health facility that is primarily focused on the care of outpatients. Clinics can be privately operated or publicly managed and funded. They typically cover the primary care needs ...

s, and pauper

Pauperism (Lat. ''pauper'', poor) is poverty or generally the state of being poor, or particularly the condition of being a "pauper", i.e. receiving relief administered under the English Poor Laws. From this, pauperism can also be more generally ...

s' graveyard

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite or graveyard is a place where the remains of dead people are buried or otherwise interred. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek , "sleeping place") implies that the land is specifically designated as a buri ...

s. The Song dynasty supported a widespread postal service

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal syst ...

that was modeled on the earlier Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BCE – CE 220) postal system to provide swift communication throughout the empire. The central government employed thousands of postal workers of various ranks to provide service for post offices and larger postal stations. In rural areas, farming peasants either owned their own plots of land, paid rents as tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

s, or were serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s on large estates.

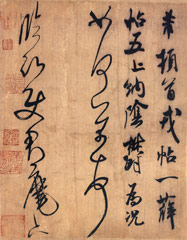

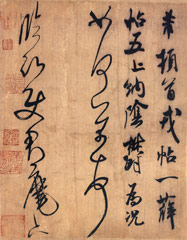

Although women were on a lower social tier than men (according to Confucian ethics), they enjoyed many social and legal privileges and wielded considerable power at home and in their own small businesses. As Song society became more and more prosperous and parents on the bride's side of the family provided larger dowries for her marriage, women naturally gained many new legal rights in ownership of property. Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers, or a surviving mother without sons, could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property. There were many notable and well-educated women, and it was a common practice for women to educate their sons during their earliest youth. The mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo taught him essentials of military strategy. There were also exceptional women writers and poets, such as Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), who became famous even in her lifetime.

Although women were on a lower social tier than men (according to Confucian ethics), they enjoyed many social and legal privileges and wielded considerable power at home and in their own small businesses. As Song society became more and more prosperous and parents on the bride's side of the family provided larger dowries for her marriage, women naturally gained many new legal rights in ownership of property. Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers, or a surviving mother without sons, could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property. There were many notable and well-educated women, and it was a common practice for women to educate their sons during their earliest youth. The mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo taught him essentials of military strategy. There were also exceptional women writers and poets, such as Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), who became famous even in her lifetime.

Religion in China

The People's Republic of China is officially an atheist state, but the government formally recognizes five religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism are recognised separately), and Islam. In the early 21 ...

during this period had a great effect on people's lives, beliefs, and daily activities, and Chinese literature on spirituality was popular. The major deities of Daoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the ''Tao'' ...

and Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, ancestral spirits, and the many deities of Chinese folk religion

Chinese folk religion, also known as Chinese popular religion comprehends a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. Vivienne Wee described it as "an empty bowl, which can variously be filled ...

were worshipped with sacrificial offerings. Tansen Sen asserts that more Buddhist monks

A ''bhikkhu'' (Pali: भिक्खु, Sanskrit: भिक्षु, ''bhikṣu'') is an ordained male in Buddhist monasticism. Male and female monastics (" nun", ''bhikkhunī'', Sanskrit ''bhikṣuṇī'') are members of the Sangha (Buddhist ...

from India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

traveled to China during the Song than in the previous Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618–907). With many ethnic foreigners travelling to China to conduct trade or live permanently, there came many foreign religions; religious minorities in China included Middle Eastern Muslims, the Kaifeng Jews

The Kaifeng Jews ( zh, t=開封猶太族, p=Kāifēng Yóutàizú; he, יהדות קאיפנג ''Yahădūt Qāʾyfeng'') are members of a small community of descendants of Chinese Jews in Kaifeng, in the Henan province of China. In the early ...

, and Persian Manichaeans.

The populace engaged in a vibrant social and domestic life, enjoying such public festivals as the Lantern Festival

The Lantern Festival ( zh, t=元宵節, s=元宵节, first=t, hp=Yuánxiāo jié), also called Shangyuan Festival ( zh, t=上元節, s=上元节, first=t, hp=Shàngyuán jié), is a Chinese traditional festival celebrated on the fifteenth d ...

and the Qingming Festival

The Qingming festival or Ching Ming Festival, also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day in English (sometimes also called Chinese Memorial Day or Ancestors' Day), is a traditional Chinese festival observed by the Han Chinese of mainland China, Hong Ko ...

. There were entertainment quarters in the cities providing a constant array of amusements. There were puppeteers, acrobats, theatre actors, sword swallowers, snake charmers, storytellers

Storyteller, story teller, or story-teller may refer to:

* A person who does storytelling

Arts and entertainment Film

*''Oidhche Sheanchais'', also called ''The Storyteller''; 1935 Irish short film

* '' Narradores de Javé'' (''Storytellers'') ...

, singers and musicians, prostitutes, and places to relax, including tea houses, restaurants, and organized banquets. People attended social clubs in large numbers; there were tea clubs, exotic food clubs, antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

and art collectors' clubs, horse-loving clubs, poetry clubs, and music clubs. Like regional cooking and cuisines in the Song, the era was known for its regional varieties of performing arts styles as well. Theatrical drama was very popular amongst the elite and general populace, although Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese (古文 ''gǔwén'' "ancient text", or 文言 ''wényán'' "text speak", meaning

"literary language/speech"; modern vernacular: 文言文 ''wényánwén'' "text speak text", meaning

"literar ...

—not the vernacular language—was spoken by actors on stage. The four largest drama theatres in Kaifeng could hold audiences of several thousand each. There were also notable domestic pastimes, as people at home enjoyed activities such as the go and xiangqi

''Xiangqi'' (; ), also called Chinese chess or elephant chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is the most popular board game in China. ''Xiangqi'' is in the same family of games as '' shogi'', '' janggi'', Western chess, '' ...

board games.

Civil service examinations and the gentry

During this period greater emphasis was laid upon thecivil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

system of recruiting officials; this was based upon degrees acquired through competitive examinations

An examination (exam or evaluation) or test is an educational assessment intended to measure a test-taker's knowledge, skill, aptitude, physical fitness, or classification in many other topics (e.g., beliefs). A test may be administered verb ...

, in an effort to select the most capable individuals for governance. Selecting men for office through proven merit was an ancient idea in China. The civil service system became institutionalized on a small scale during the Sui and Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) ...

dynasties, but by the Song period, it became virtually the only means for drafting officials into the government. The advent of widespread printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

helped to widely circulate Confucian teachings and to educate more and more eligible candidates for the exams. This can be seen in the number of exam takers for the low-level prefectural exams rising from 30,000 annual candidates in the early 11th century to 400,000 candidates by the late 13th century. The civil service and examination system allowed for greater meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achiev ...

, social mobility

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society ...