Sir Hugh Beadle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Thomas Hugh William Beadle, (6 February 1905 – 14 December 1980) was a Rhodesian lawyer, politician and judge who served as Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia from March 1961 to November 1965, and as Chief Justice of Rhodesia from November 1965 until April 1977. He came to international prominence against the backdrop of Rhodesia's

After returning to Rhodesia, Beadle took an interest in politics; he joined the United Party, created from the former Rhodesia Party and the conservative faction of the Reform Party to contest the 1934 general election. He was attracted to the United Party not so much by its policies but by his admiration for its leading figures—he considered the Prime Minister

After returning to Rhodesia, Beadle took an interest in politics; he joined the United Party, created from the former Rhodesia Party and the conservative faction of the Reform Party to contest the 1934 general election. He was attracted to the United Party not so much by its policies but by his admiration for its leading figures—he considered the Prime Minister

Beadle filled the seat on the High Court bench vacated by Sir Robert Tredgold, who had just been appointed Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia. Despite his close relationship with Huggins, Beadle had strong misgivings regarding

Beadle filled the seat on the High Court bench vacated by Sir Robert Tredgold, who had just been appointed Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia. Despite his close relationship with Huggins, Beadle had strong misgivings regarding

Britain granted independence to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, renamed Zambia and Malawi respectively, under black majority governments in 1964. As independence talks between the British and Southern Rhodesian governments continued with little progress, speculation began to mount that the colonial government might attempt a

Britain granted independence to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, renamed Zambia and Malawi respectively, under black majority governments in 1964. As independence talks between the British and Southern Rhodesian governments continued with little progress, speculation began to mount that the colonial government might attempt a  Smith and Wilson made little progress towards a settlement during 1964 and 1965; each accused the other of being unreasonable. The RF won a decisive victory in the May 1965 general election. After efforts to forge a compromise in London in early October 1965 failed, Wilson, desperate to avert UDI, travelled to Salisbury later that month to continue negotiations. Beadle's "irrepressible ingenuity led to an incredible succession of proposals for a settlement", Wilson recalled, but these talks also failed. The two sides agreed on an investigatory Royal Commission, possibly chaired by Beadle, to recommend a path towards independence, but could not settle on the terms. Beadle continued to seek a compromise, and on 8 November persuaded Smith to allow him to go to London to meet Wilson again. Beadle told Wilson that he thought Smith was personally disposed to continue talks but under pressure from some of his ministers to abandon negotiations. Wilson told the British

Smith and Wilson made little progress towards a settlement during 1964 and 1965; each accused the other of being unreasonable. The RF won a decisive victory in the May 1965 general election. After efforts to forge a compromise in London in early October 1965 failed, Wilson, desperate to avert UDI, travelled to Salisbury later that month to continue negotiations. Beadle's "irrepressible ingenuity led to an incredible succession of proposals for a settlement", Wilson recalled, but these talks also failed. The two sides agreed on an investigatory Royal Commission, possibly chaired by Beadle, to recommend a path towards independence, but could not settle on the terms. Beadle continued to seek a compromise, and on 8 November persuaded Smith to allow him to go to London to meet Wilson again. Beadle told Wilson that he thought Smith was personally disposed to continue talks but under pressure from some of his ministers to abandon negotiations. Wilson told the British

Michael Stewart, Wilson's Foreign Secretary, recommended that Britain take preliminary steps towards removing Beadle from the Privy Council if the Chief Justice did not resign or dissociate himself from the republic "within a week or two" after the new constitution came into force. Given the gravity of such an action—only one Privy Counsellor,

Michael Stewart, Wilson's Foreign Secretary, recommended that Britain take preliminary steps towards removing Beadle from the Privy Council if the Chief Justice did not resign or dissociate himself from the republic "within a week or two" after the new constitution came into force. Given the gravity of such an action—only one Privy Counsellor,

Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state which it is secedin ...

(UDI) from Britain in November 1965, upon which he initially stood by the British Governor Sir Humphrey Gibbs

Sir Humphrey Vicary Gibbs, (22 November 19025 November 1990), was the penultimate Governor of the colony of Southern Rhodesia, from 24 October 1964 simply Rhodesia, who served until, and opposed, the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI ...

as an adviser; he then provoked acrimony in British government circles by declaring Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

's post-UDI administration legal in 1968.

Born and raised in the Southern Rhodesian capital Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, Beadle read law in the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

and in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

before commencing practice in Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council ...

in 1931. He became a member of the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Rhodesia was the legislature of Southern Rhodesia and then Rhodesia from 1924 to 1970.

Background

In 1898, the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Council, Southern Rhodesia's first elected representative body, was foun ...

for Godfrey Huggins

Godfrey Martin Huggins, 1st Viscount Malvern (6 July 1883 – 8 May 1971), was a Rhodesian politician and physician. He served as the fourth Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1933 to 1953 and remained in office as the first Prime Minis ...

's ruling United Party in 1939. Appointed Huggins's Parliamentary Private Secretary in 1940, he retained that role until 1946, when he became Minister of Internal Affairs and Justice; the Education and Health portfolios were added two years later. He retired from politics in 1950 to become a Judge of the High Court of Southern Rhodesia. In 1961, he was knighted and appointed Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia; three years later he became president of the High Court's new Appellate Division and a member of the British Privy Council.

Beadle held the Rhodesian Front, the governing party from 1962, in low regard, dismissing its Justice Minister Desmond Lardner-Burke

Desmond William Lardner-Burke ID (17 October 1909 – 1984) was a politician in Rhodesia.

Early years

Desmond Lardner-Burke was born in Kimberley in the Cape of Good Hope on 17 October 1909, and was educated at St. Andrew's College, Grahamsto ...

as a "small time country solicitor". As independence talks between Britain and Southern Rhodesia gravitated towards stalemate, Beadle repeatedly attempted to arrange a compromise. He continued these efforts after UDI, and brought Harold Wilson and Smith together for talks aboard . The summit failed; Wilson afterwards castigated Beadle for not persuading Smith to settle.

Beadle's ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' recognition of the post-UDI government in Rhodesia in 1968 outraged the Wilson administration and drew accusations from the British Prime Minister and others that he had furtively supported UDI all along. His true motives remain the subject of speculation. After Smith declared a republic in 1970, Beadle continued as Chief Justice; he was almost removed from the Imperial Privy Council, but kept his place following Wilson's 1970 electoral defeat soon after. Beadle retired in April 1977 and thereafter sat as an acting judge in special trials for terrorist offences.

Early life and education

Thomas Hugh William Beadle (generally known as Hugh) was born inSalisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kno ...

on 6 February 1905, the only son and eldest child of Arthur William Beadle and his wife Christiana Maria (''née'' Fischer). He had two sisters. The family was politically conservative and favoured joining the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

during the latter years of Company rule, sharing a firm consensus that Sir Charles Coghlan and his responsible government movement were, in Beadle's recollection, "a pretty wild bunch of jingoes". Responsible government ultimately prevailed in the 1922 referendum of the mostly white electorate, and Southern Rhodesia became a self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to ...

the following year.

After attending Salisbury Boys' School, Milton High School in Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council ...

and Diocesan College

The Diocesan College (commonly known as Bishops) is a private, English medium, boarding and day high school for boys situated in the suburb of Rondebosch in Cape Town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The school was established on ...

, Rondebosch

Rondebosch is one of the Southern Suburbs of Cape Town, South Africa. It is primarily a residential suburb, with shopping and business districts as well as the main campus of the University of Cape Town.

History

Four years after the first Dutch s ...

, Beadle studied law at the University of Cape Town

The University of Cape Town (UCT) ( af, Universiteit van Kaapstad, xh, Yunibesithi ya yaseKapa) is a public research university in Cape Town, South Africa. Established in 1829 as the South African College, it was granted full university statu ...

. He completed his Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Ch ...

degree in 1928, then continued his studies in England as a Rhodes Scholar at The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassical architecture, ...

. There he played rugby and tennis for the college, boxed for the university and qualified as a pilot with the Oxford University Air Squadron

The Oxford University Air Squadron, abbreviated Oxford UAS, or OUAS, formed in 1925, is the training unit of the Royal Air Force at the University of Oxford and forms part of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. OUAS is one of fifteen Universi ...

. On 16 July 1928, Beadle received his commission as a Pilot Officer (Class AA) in the Reserve of Air Force Officers, Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

. On 16 January 1930, he was promoted to the rank of Flying Officer, was transferred to Class C in 1931 and completed his service with the RAF on 16 July 1933. He graduated with a second-class Bachelor of Civil Law

Bachelor of Civil Law (abbreviated BCL, or B.C.L.; la, Baccalaureus Civilis Legis) is the name of various degrees in law conferred by English-language universities. The BCL originated as a postgraduate degree in the universities of Oxford and Cam ...

degree in 1930, and soon after was called to the English bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

. He briefly read

Read

Read may refer to:

* Reading, human cognitive process of decoding symbols in order to construct or derive meaning

* Read (automobile), an American car manufactured from 1913 to 1915

* Read (biology), an inferred sequence of base pairs of ...

in London chambers before commencing practice in Bulawayo in 1931. In 1934 he married Leonie Barry, a farmer's daughter from Barrydale in the Cape of Good Hope; they had two daughters.

Political and judicial career

MP and Cabinet minister

After returning to Rhodesia, Beadle took an interest in politics; he joined the United Party, created from the former Rhodesia Party and the conservative faction of the Reform Party to contest the 1934 general election. He was attracted to the United Party not so much by its policies but by his admiration for its leading figures—he considered the Prime Minister

After returning to Rhodesia, Beadle took an interest in politics; he joined the United Party, created from the former Rhodesia Party and the conservative faction of the Reform Party to contest the 1934 general election. He was attracted to the United Party not so much by its policies but by his admiration for its leading figures—he considered the Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins

Godfrey Martin Huggins, 1st Viscount Malvern (6 July 1883 – 8 May 1971), was a Rhodesian politician and physician. He served as the fourth Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1933 to 1953 and remained in office as the first Prime Minis ...

"a man of the calibre I think of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

". The Southern Rhodesian electoral system allowed only those who met certain financial and educational qualifications to vote. The criteria were applied equally to all regardless of race, but since most black citizens did not meet the set standards, the electoral roll and the colonial Legislative Assembly were overwhelmingly from the white minority (about 5% of the population). The United Party broadly represented commercial interests, civil servants and the professional classes.

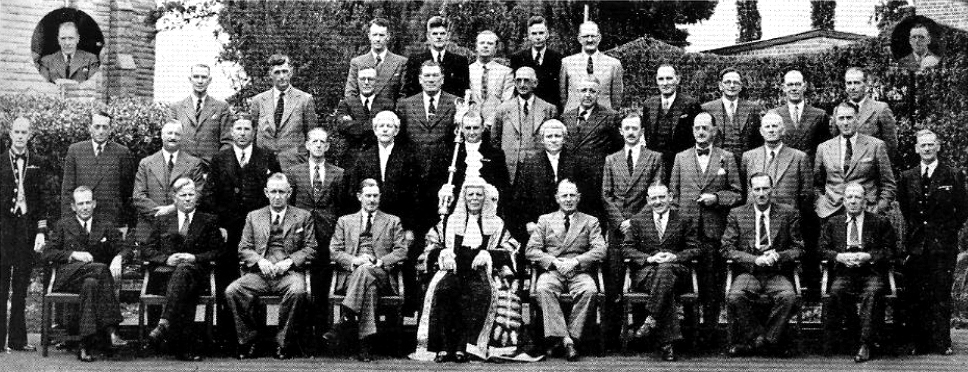

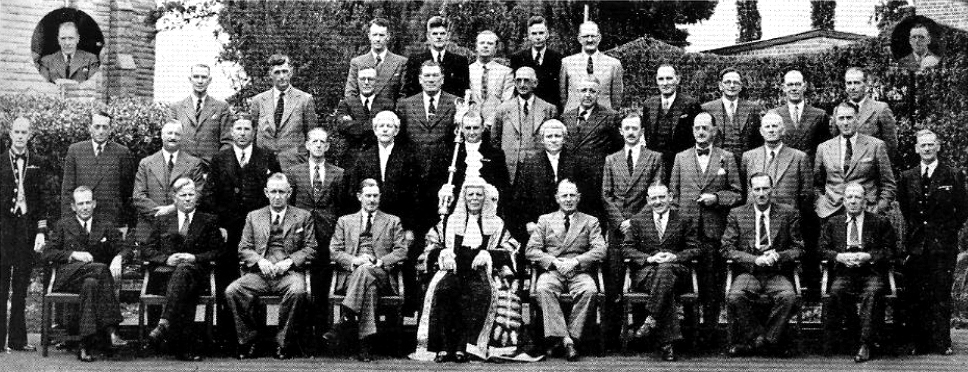

Beadle stood in Bulawayo South in the 1934 election, challenging Harry Davies, the Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

leader. Davies defeated Beadle by 458 votes to 430, but the United Party won decisively elsewhere and formed a new government with 24 out of the 30 parliament seats. Huggins, who remained prime minister, held Beadle in high regard and made him a close associate. In the 1939 election, Beadle won a three-way contest in Bulawayo North with 461 votes out of 869, and became a United Party MP. Beadle was seconded to the Gold Coast Regiment

The Ghana Regiment is an infantry regiment that forms the main fighting element of the Ghanaian Army (GA).

History

The regiment was formed in 1879 as the Gold Coast Constabulary, from personnel of the Hausa Constabulary of Southern Nigeria, to pe ...

with the rank of temporary captain following the outbreak of the Second World War, but was released from military service at the request of the Southern Rhodesian government to serve as Huggins's Parliamentary Secretary, "with access to all ministers and top-ranking officials on the PM's business to speed up affairs". He held this post from 1940 to 1946, during which time he was also Deputy Advocate General for the Southern Rhodesian armed forces. In the 1945 New Year Honours

The 1945 New Year Honours were appointments by many of the Commonwealth realms of King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced on 1 January 1945 for the Britis ...

he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(OBE). For his service during the war, Beadle was also honoured by the King of the Hellenes

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolish ...

with the rank of Officer of the Order of the Phoenix.

In the first post-war election in 1946, Beadle defeated Labour's Cecil Maurice Baker in Bulawayo North by 666 votes to 196. He was appointed Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

and Minister of Internal Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

. The same year he was made a King's Counsel. Two years later, after retaining his seat in the 1948 election with a large majority, he was assigned two more portfolios, those of Education and Health. Around this time he turned down an approach from a group of Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and rebel United Party MPs to challenge Huggins's premiership. Beadle had entered the Cabinet at a time when relations between the United Party and the British Labour Party were warming. He formed a good relationship with Aneurin Bevan, the UK Minister of Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Coun ...

, and put considerable work into attempting to create a Southern Rhodesian system similar to National Insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

in Britain. These efforts were largely unsuccessful, but did lead to a maternity grant for white mothers, nicknamed the "Beadle baby scheme". Beadle retired from politics in 1950 to accept a seat on the Southern Rhodesian High Court. This decision surprised many of his contemporaries; Beadle would explain later that he left politics as he did not feel he would work well under his United Party colleague Edgar Whitehead

Sir Edgar Cuthbert Fremantle Whitehead, (8 February 1905 – 22 September 1971) was a Rhodesian politician. He was a longstanding member of the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Assembly, although his career was interrupted by other posts and b ...

, whose subsequent rise to the premiership he correctly predicted. Having served for more than three years as a member of the Executive Council of Southern Rhodesia, he was granted the right in August 1950 to retain the title "The Honourable

''The Honourable'' (British English) or ''The Honorable'' ( American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of certain ...

" for life.

Judicial career

Beadle filled the seat on the High Court bench vacated by Sir Robert Tredgold, who had just been appointed Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia. Despite his close relationship with Huggins, Beadle had strong misgivings regarding

Beadle filled the seat on the High Court bench vacated by Sir Robert Tredgold, who had just been appointed Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia. Despite his close relationship with Huggins, Beadle had strong misgivings regarding Federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasala ...

, which became Huggins's flagship project. Beadle argued that since the British government would never devolve indigenous African affairs to Federal responsibility, native policy in the three territories would never be co-ordinated, meaning "the thing was bound to crash". Nevertheless, Huggins sent him to London in 1949 to discuss the legal problems of the proposed Federation with the British government. Beadle later expressed regrets that he had not played a bigger role in drawing up the constitution for the Federation, which was inaugurated as an indissoluble entity in 1953, following a mostly white referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

in Southern Rhodesia. Huggins spent three years as Federal Prime Minister before retiring in 1956. Whitehead became Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia in 1958.

After Leonie's death in 1953, Beadle married Olive Jackson, of Salisbury, in 1954. He later said that he was repeatedly asked to resign from the bench to become the Federal Minister of Law or stand for Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, but "didn't regard any of the issues as crucial enough to warrant my going back". Beadle's biographer Claire Palley describes him as "a learned, fair but also adventurous judge". He was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the 1957 New Year Honours. In August 1959, amid rising black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

and opposition to the Federation, particularly in the two northern territories, Beadle chaired a three-man tribunal on the Southern Rhodesian government's preventive detention

Preventive detention is an imprisonment that is putatively justified for non- punitive purposes, most often to prevent (further) criminal acts.

Types of preventive detention

There is no universally agreed definition of preventive detention, and m ...

of black nationalist leaders without trial during the disturbances. He upheld the government's actions, reporting that the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress

The Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC) was a political party active between 1957–1959 in Southern Rhodesia (now modern-day Zimbabwe). Committed to the promotion of indigenous African welfare, it was the first fully fledged ...

had disseminated "subversive propaganda", encouraged racial hatred, intimidated people into joining and undermined the authority of tribal chiefs, government officials and police.

In 1960 Beadle was a member of the Monckton Commission on the Federation's future. According to Aidan Crawley

Aidan Merivale Crawley (10 April 1908 – 3 November 1993) was a British journalist, television executive and editor, and politician. He was a member of both of Britain's major political parties: the Labour Party and Conservative Party, and wa ...

, a British member of the commission, Beadle began the process "as a radical advocate of white supremacy" but later expressed markedly different views. The commissioners "hardly agreed on anything", in Beadle's recollection. While not recommending dissolution, the Monckton report was strongly critical of the Federation. It advocated a wide range of reforms, rejected any further advance towards Federal independence until these were implemented, and called for the territories to be permitted to secede if opposition continued. Beadle was knighted in the 1961 New Year Honours and the same year appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Southern Rhodesia. A primary school in Bulawayo was named after him. In ''Mehta v. City of Salisbury'' (1961), a case challenging the racial segregation of a public swimming pool, Beadle decided that apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

made precedents in South African case law invalid, ruled that the plaintiff's dignity had been unlawfully affronted, and awarded him damages. Following continued black nationalist opposition to the Federation, particularly in Nyasaland, the British government announced in 1962 that Nyasaland would be allowed to secede. This was soon extended to Northern Rhodesia as well, and at the end of 1963 the Federation was dismantled.

Whitehead's United Federal Party was defeated in the 1962 Southern Rhodesian general election by the Rhodesian Front (RF), an all-white, firmly conservative party led by Winston Field

Winston Joseph Field (6 June 1904 – 17 March 1969) was a Rhodesian politician who served as the seventh Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia. Field was a former Dominion Party MP who founded the Rhodesian Front political party with Ian Smith.

...

whose declared goal was independence for Southern Rhodesia without major constitutional changes and without commitment to any set timetable regarding black majority rule. RF proponents downplayed black nationalist grievances regarding land ownership and segregation, and argued that despite the racial imbalance in domestic politics—whites made up 5% of the population, but over 90% of registered voters—the electoral system was not racist as the franchise was based on financial and educational qualifications rather than ethnicity. Beadle expressed an extremely low opinion of the RF. Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

, who replaced Field as prime minister in 1964, was in Beadle's eyes an unconvincing leader; Desmond Lardner-Burke

Desmond William Lardner-Burke ID (17 October 1909 – 1984) was a politician in Rhodesia.

Early years

Desmond Lardner-Burke was born in Kimberley in the Cape of Good Hope on 17 October 1909, and was educated at St. Andrew's College, Grahamsto ...

, the Justice Minister, was a "fascist" and a "small time country solicitor ... incapable of producing correct documents for an undefended divorce action". The same year Smith took over, Beadle became a member of the Privy Council in London and president of the new Appellate Division of the Southern Rhodesian High Court. In this latter role he blocked a Legislative Assembly act to extend periods of preventive restriction outside times of emergency, ruling it against the declaration of rights contained in Southern Rhodesia's 1961 constitution.

UDI

Britain granted independence to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, renamed Zambia and Malawi respectively, under black majority governments in 1964. As independence talks between the British and Southern Rhodesian governments continued with little progress, speculation began to mount that the colonial government might attempt a

Britain granted independence to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, renamed Zambia and Malawi respectively, under black majority governments in 1964. As independence talks between the British and Southern Rhodesian governments continued with little progress, speculation began to mount that the colonial government might attempt a unilateral declaration of independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state which it is secedin ...

(UDI) if no accommodation could be found. The British High Commissioner in Salisbury, J B Johnston, had few doubts about how Beadle would respond to such an act, writing that he was "quite certain that no personal considerations would deflect him for a moment from administering the law with absolute integrity." Arthur Bottomley

Arthur George Bottomley, Baron Bottomley, OBE, PC (7 February 1907 – 3 November 1995) was a British Labour politician, Member of Parliament and minister.

Early life

Before entering parliament he was a trade union organiser of the Nationa ...

, the British Сommonwealth Secretary, took a similar line, describing Beadle to the Prime Minister Harold Wilson as "a staunch constitutionalist" who would be disposed to "frustrate any illegal action by Mr Smith's government".

Beadle told Wilson that he and the judiciary would stand by the law in the event of a UDI, but that he expected the armed forces and police to side with the post-UDI authorities. He thought UDI would be a political and economic mistake for Rhodesia, and attempted to dissuade Smith from this course of action, but at the same time asserted that if UDI occurred it was "not the function of a court to attempt to end the revolution and restore legality". He warned his High Court colleagues that he would not direct "a judicial rebellion against the Rhodesian government".

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

that Beadle had provided "wise advice" to both governments, and was "welcome nthis country not only for his sagacity, judgement, and humanity but as a man with the courage of a lion."

Beadle later wrote to his fellow High Court judge Benjamin Goldin that he thought he had "saved the situation" by going to London, having persuaded Wilson to give some ground on the terms for the Royal Commission, but his trip alarmed the pro-UDI camp in the Rhodesian Cabinet, who feared that Beadle might be carrying a message to the Governor Sir Humphrey Gibbs

Sir Humphrey Vicary Gibbs, (22 November 19025 November 1990), was the penultimate Governor of the colony of Southern Rhodesia, from 24 October 1964 simply Rhodesia, who served until, and opposed, the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI ...

telling him to prorogue

Prorogation in the Westminster system of government is the action of proroguing, or interrupting, a parliament, or the discontinuance of meetings for a given period of time, without a dissolution of parliament. The term is also used for the period ...

parliament. Smith and his Cabinet declared independence on 11 November 1965, while Beadle was at Lusaka Airport

Lusaka (; ) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was about 3.3 milli ...

on his way home. Smith later rejected the suggestion that Beadle could have had anything significant to tell them on his return, saying that "the only thing that Beadle could have done when he got back was to have talked us out of insisting on our questions".

Before announcing UDI to the nation, Smith, Lardner-Burke and the Deputy Prime Minister Clifford Dupont

Clifford Walter Dupont, GCLM, ID (6 December 1905 – 28 June 1978) was a British-born Rhodesian politician who served in the internationally unrecognised positions of officer administrating the government (from 1965 until 1970) and president ...

visited Gibbs at Government House to inform him personally and ask him to resign. Gibbs made clear that he would not do so, but indicated that he would vacate Government House and return to his farm. When Beadle arrived later in the day, he not only persuaded Gibbs to stay at the official residence, but moved in himself to provide advice and moral support. On Beadle's counsel, Gibbs instructed those responsible for law and order in Rhodesia to stay at their posts and carry on as normal. When the Governor showed no sign of stepping down, Smith's government effectively replaced him with Dupont, appointing the latter to the post of Officer Administering the Government

An administrator (administrator of the government or officer administering the government) in the constitutional practice of some countries in the Commonwealth is a person who fulfils a role similar to that of a governor or a governor-general.

...

created by the 1965 constitution attached to UDI. Lardner-Burke asked Beadle to administer the oath of allegiance to Dupont, but was rebuffed; Beadle said he would be committing a criminal offence if he did so.

The UK government introduced extensive economic and political sanctions against Rhodesia and indicated that any dialogue had to take place through Gibbs. Beadle was told to liaise with Lardner-Burke regarding any proposals Smith's government might have. Beadle would later recount that the post-UDI government briefly threatened him, telling him to "go now, otherwise you lose your job", but he was ultimately left alone. The Chief Justice noted in his diary that Smith's government was "not prepared to force showdown with the judges".

Madzimbamuto case and ''Tiger'' talks

During the immediate post-UDI period Beadle, in his role as Chief Justice, occupied a unique position as he could speak directly with all the main players—Gibbs, Smith and Wilson. He became the main intermediary between them, and received adormant commission

A dormant commission is a commission in a Commonwealth realm that lies dormant or sleeping until it is triggered by a particular event.

Historically, a dormant commission was given in relation to a military command. During the Crimean War, Sir ...

from the UK government to replace Gibbs as governor in case of necessity. He visited London in January 1966 and, according to Wilson's Attorney General Elwyn Jones, was "scornful of the 1965 constitution". Some in Rhodesia criticised Beadle for going to London, or accused him of siding with Gibbs against Smith. The Chief Justice insisted that he was just trying to do his best for Rhodesia, a claim Smith accepted, saying Beadle "thought more of his country than of his position". The UK Foreign Office remained wary, speculating in a January 1966 report that while the British government hoped to reclaim Rhodesia "in such a way that policy and thinking is reoriented, racial attitudes changed, and the path to majority rule firmly laid," the Chief Justice "would be content to see a 1961-type constitution, without independence, remain for a long time".

Beadle summarised the Rhodesian judiciary's position in light of UDI by saying simply that the judges would carry on with their duties "according to the law", but this non-committal stance was challenged by legal cases heard at the High Court. The first of these was '' Madzimbamuto v. Lardner-Burke N. O. and Others'', concerning Daniel Madzimbamuto, a black nationalist detained without trial five days before UDI under emergency powers. When Lardner-Burke's ministry prolonged the state of emergency in February 1966, Madzimbamuto's wife appealed for his release, arguing that since the UK government had declared UDI illegal and outlawed the Rhodesian government, the state of emergency (and, by extension, her husband's imprisonment) had no legal basis. The High Court's General Division ruled on 9 September 1966 that the UK retained legal sovereignty, but that to "avoid chaos and a vacuum in the law" the Rhodesian government should be considered to be in control of law and order to the same extent as before UDI. Madzimbamuto appealed to Beadle's Appellate Division, which considered the case over the next year and a half.

Beadle arranged "talks about talks" between the British and Rhodesian governments during 1966, which led to Smith and Wilson meeting personally aboard HMS ''Tiger'' off Gibraltar between 2 and 4 December. Beadle had to be hoisted aboard because of a back injury. Negotiations snagged primarily over the matter of the transition. Wilson insisted on the abandonment of the 1965 constitution, the dissolution of the post-UDI government and a period under a British Governor—conditions that Smith saw as tantamount to surrender, particularly as the British proposed to draft and introduce the new constitution only after a fresh test of opinion under UK control. Indeed, Smith had warned Beadle before the summit that unless he "could assure his people that a reasonable constitution had been agreed", he would feel unable to settle. Smith said he could not agree without first consulting his ministers in Salisbury, infuriating Wilson, who declared that a central condition of the talks had been that he and Smith would have plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the wor ...

powers to make a deal.

Beadle agreed with Smith that a deal ending UDI without any prior agreement on the replacement constitution would meet with widespread opposition among white Rhodesians, but still felt that Salisbury should agree. He asked Smith to commend the terms to his colleagues in Salisbury, speculating that if he did the Cabinet would surely accept. Smith refused to make such a commitment, much to the disappointment of Beadle and Gibbs, and signed the final document only to acknowledge it as an accurate record. Wilson was furious with Beadle, feeling that he should have taken a far firmer line to persuade Smith to settle; after Beadle left the meeting, Wilson said that he "could not understand how any man could have a slipped disc whom Providence had failed to provide with a backbone". Beadle and Gibbs urged Smith to reconsider during the journey home, but made little headway.

During the Rhodesian Cabinet meeting on the proposals, the judges were kept informed by the "expression on Sir Hugh's face and from comments of increasing despair", Goldin later wrote; the Chief Justice "spent the whole day in his chambers looking more anxious and despondent after each occasion on which he was smuggled into the Cabinet meeting to explain the meaning or effect of particular provisions". On 5 December 1966, when Beadle heard at Government House that Smith's ministers had rejected the terms, he stood "as though pole-axed", Gibbs's Private Secretary

A private secretary (PS) is a civil servant in a governmental department or ministry, responsible to a secretary of state or minister; or a public servant in a royal household, responsible to a member of the royal family.

The role exists in ...

Sir John Pestell recalled, and appeared close to collapse. The judge's wife and daughter helped him to slowly return to his room.

''De facto'' decision; rejection of royal prerogative

The United Nations instituted mandatory economic sanctions against Rhodesia in December 1966. Over the next year British diplomatic activity regarding Rhodesia was diminished; the UK government's stated policy shifted towards NIBMAR—"no independence before majority rule

No independence before majority rule (abbreviated NIBMAR) was a policy adopted by the United Kingdom requiring the implementation of majority rule in a colony, rather than rule by the white colonial minority, before the empire granted independe ...

". Beadle grappled with the Rhodesian problem privately and in correspondence, attempting to reconcile the Smith administration's control over the country with the unconstitutional nature of UDI. Erwin Griswold

Erwin Nathaniel Griswold (; July 14, 1904 – November 19, 1994) was an American appellate attorney who argued many cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Griswold served as Solicitor General of the United States (1967–1973) under Presidents Lynd ...

, the United States Solicitor General

The solicitor general of the United States is the fourth-highest-ranking official in the United States Department of Justice. Elizabeth Prelogar has been serving in the role since October 28, 2021.

The United States solicitor general represent ...

, wrote to him that as he saw it the Rhodesian judges could not recognise the post-UDI government as ''de facto'' while also claiming to act under the Queen's commission.

Ruling on Madzimbamuto's appeal in January 1968, Beadle and three other judges decided that Smith's post-UDI order was not ''de jure'' but should be acknowledged as the ''de facto'' government by virtue of its "effective control over the state's territory". Sir Robert Tredgold, the former Southern Rhodesian and Federal Chief Justice, told Gibbs that Beadle had thereby "sold the pass" and "should be asked to leave Government House". The following month, considering the fate of James Dhlamini, Victor Mlambo and Duly Shadreck, three black Rhodesians sentenced to death before UDI for murder and terrorist offences, Beadle upheld Salisbury's power to execute the men. Whitehall reacted by announcing on 1 March 1968 that at the request of the UK government, the Queen had exercised the royal prerogative of mercy

In the English and British tradition, the royal prerogative of mercy is one of the historic royal prerogatives of the British monarch, by which they can grant pardons (informally known as a royal pardon) to convicted persons. The royal prer ...

and commuted the sentences to life imprisonment. Dhlamini and the others promptly applied for a permanent stay of execution.

At the hearing for Dhlamini and Mlambo on 4 March 1968, Beadle dismissed the statement from London, saying it was a decision by the UK government and not the Queen herself, and that in any case the 1961 constitution had transferred the prerogative of mercy from Britain to the Rhodesian Executive Council. "The present government is the fully ''de facto'' government and as such is the only power that can exercise the prerogative," he concluded. "It would be strange indeed if the United Kingdom government, exercising no internal power in Rhodesia, were given the right to exercise the prerogative of clemency." The Judge President Sir Vincent Quenet and Justice Hector Macdonald

Major-General Sir Hector Archibald MacDonald, ( gd, Eachann Gilleasbaig MacDhòmhnaill; 4 March 1853 – 25 March 1903), also known as Fighting Mac, was a Scottish soldier.

The son of a crofter, MacDonald left school before he was 15, en ...

agreed, and the application was dismissed. Dhlamini, Mlambo and Shadreck were hanged two days later.

Justice John Fieldsend of the High Court's General Division resigned in protest, writing to Gibbs that he no longer believed the High Court to be defending the rights of Rhodesian citizens. Beadle told reporters that "Her Majesty is quite powerless in this matter," and that "it is to be deplored that the Queen was brought into this". At Government House, the Chief Justice berated Gibbs for "dragging the Queen into the political argument". To the Governor's astonishment, Beadle conceded that for some time he had no longer considered himself to be sitting under the 1961 constitution, but had not made this clear as he had not fully accepted the 1965 constitution as valid. Gibbs told him to leave Government House forthwith. They never met again.

In his analysis of Beadle's behaviour, Manuele Facchini suggests that the Chief Justice considered the matter from a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

-style viewpoint—by stressing the 1961 constitution and the rights held by Salisbury thereunder, he was repudiating not the royal prerogative itself, but rather the attempt to exercise it at the behest of British rather than Rhodesian ministers. Kenneth Young comments that the British government's involvement of the Queen inadvertently strengthened the post-UDI authorities' position; outraged, many in Rhodesia who had heretofore rejected UDI now threw their weight behind the RF. Beadle, deeply disillusioned, wrote to a friend that he was "thoroughly fed up with the way the Wilson government had behaved in this whole affair."

''De jure'' decision

Madzimbamuto petitioned for the right to appeal against his detention to the Privy Council in London; the Rhodesian Appellate Division ruled that he had no right to do so, but the Privy Council considered his case anyway. It ruled in his favour on 23 July 1968, deciding that orders for detention made by the Rhodesian government were invalid regardless of whether they were under the 1961 or 1965 constitution, and that Madzimbamuto was illegally detained. Harry Elinder Davies, one of the Rhodesian judges, announced on 8 August that the Rhodesian courts would not consider this ruling binding as they no longer accepted the Privy Council as part of the Rhodesian judicial hierarchy. Justice J R Dendy Young resigned in protest at Davies's ruling on 12 August and four days later became Chief Justice of Botswana. Madzimbamuto would remain in prison until 1974. Beadle and his judges granted full ''de jure'' recognition to the post-UDI government on 13 September 1968, while rejecting the appeals of 32 black nationalists who one month earlier had been convicted of terrorist offences and sentenced to death. Beadle declared that while he believed the Rhodesian judiciary should respect rulings of the Privy Council "so far as possible", the judgement of 23 July had made it legally impossible for Rhodesian judges to continue under the 1961 constitution. He asserted that as he could not countenance a legal vacuum, the only alternative was the 1965 constitution. Referring to the Privy Council's decision that the UK might yet remove the post-UDI government, he said that "on the facts as they exist today, the only prediction which this court can make is that sanctions will not succeed in overthrowing the present government ... and that there are no other factors which might succeed in doing so". UDI, the associated 1965 constitution and the government were thereafter considered ''de jure'' by the Rhodesian legal system. The British Commonwealth Secretary George Thomson expressed outrage, accusing Beadle and the other judges of breaching "the fundamental laws of the land", while Gibbs stated that since his position as governor existed under the 1961 constitution he could only reject the ruling. An internal UK Foreign Office memorandum rejected Beadle's argument but recognised his belief that "because of the effect of the effluxion of time, he was entitled to take a different view", and concluded that the Chief Justice's argument was "sufficiently plausible to make it difficult to say that that position is manifestly improper or that, in adopting it, Sir Hugh Beadle is manifestly guilty of misconduct." Beadle explained in a 1972 interview: "We had been doing our best to try and uphold the law and when the thing was in the revolutionary stage we dug our toes in, we wouldn't budge. But then as the government became more and more entrenched we had to apply the principle of law, which says that if a revolution succeeds the law changes with it. Yet because we accepted the inevitable we're blamed by a lot of people for being responsible for the revolution, which is a very different thing."Threatened removal from Privy Council; republican Chief Justice

Beadle's acceptance of the post-UDI order effectively placed him on the side of the RF and removed any chance of his regaining an intermediary role with Wilson. The British Prime Minister minimised the political impact of the Chief Justice's decision by presenting it as evidence that Beadle had furtively supported UDI all along, and subsequently excluded him from the diplomatic dialogue. Wilson pursued a second initiative which led to a fresh round of talks with Smith off Gibraltar aboard HMS ''Fearless'' in October 1968. Marked progress towards agreement was made but the Rhodesian delegation demurred on a new British proposal, the "double safeguard". This would involve elected black Rhodesians controlling a blocking quarter in the Rhodesian parliament, with the power to veto retrogressive legislation, and thereafter having the right to appeal passed bills to the Privy Council in London. Smith's team accepted the principle of the blocking quarter but agreement could not be reached on the technicalities; the involvement of the Privy Council was rejected by Smith as a "ridiculous" provision that would prejudice Rhodesia's sovereignty. The talks ended without success. Smith's government held areferendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on 20 June 1969 in which the mostly white electorate overwhelmingly voted in favour of both a new constitution and the declaration of a republic. Four days later the UK Foreign Office released Gibbs from his post, withdrew the British residual mission in Salisbury and closed the post-UDI government's representative office at Rhodesia House

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

in London. The 1969 constitution introduced a President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

as head of state, a multiracial senate, separate black and white electoral rolls (each with qualifications) and a mechanism whereby the number of black MPs would increase in line with the proportion of income tax revenues paid by black citizens. This process would stop once blacks had the same number of seats as whites; the declared goal was not majority rule, but rather "parity between the races".

Michael Stewart, Wilson's Foreign Secretary, recommended that Britain take preliminary steps towards removing Beadle from the Privy Council if the Chief Justice did not resign or dissociate himself from the republic "within a week or two" after the new constitution came into force. Given the gravity of such an action—only one Privy Counsellor,

Michael Stewart, Wilson's Foreign Secretary, recommended that Britain take preliminary steps towards removing Beadle from the Privy Council if the Chief Justice did not resign or dissociate himself from the republic "within a week or two" after the new constitution came into force. Given the gravity of such an action—only one Privy Counsellor, Edgar Speyer

Sir Edgar Speyer, 1st Baronet (7 September 1862 – 16 February 1932) was an American-born financier and philanthropist. Barker 2004. He became a British subject in 1892 and was chairman of Speyer Brothers, the British branch of the Speyer fami ...

, was struck off the list during the 20th century—and the likelihood that accusations of vindictiveness would result, the British government was loath to do this, and hoped that Beadle would remove the need for it by resigning.

Smith officially declared a republic on 2 March 1970, and on 10 April the RF was decisively returned to power in the first republican election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

, winning all 50 white seats out of a total of 66. Six days later, Dupont was sworn in as the first president of Rhodesia. British officials learned only from the Rhodesian radio that Dupont's oath of office was administered not by Beadle but by the "Acting Chief Justice", Hector Macdonald. Beadle's absence prompted speculation in British quarters, but this promptly dissipated after ''The Rhodesia Herald

''The Herald'' is a state-owned daily newspaper published in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe.

History

Origins

The newspaper's origins date back to the 19th century. Its forerunner was launched on 27 June 1891 by William Fairbridge for the Ar ...

'' reported on 29 April that a High Court farewell to Sir Vincent Quenet, a retiring judge, would be presided over by the republic's Chief Justice Sir Hugh Beadle.

On 6 May 1970, Stewart suggested to Wilson that they should formally advise the Queen to remove Beadle from the Privy Council. Wilson resolved to wait until after the British general election the following month. This decision proved decisive for Beadle as, to the surprise of many, the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

won the election, and Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

replaced Wilson as prime minister. Heath's government decided against removing Beadle from the Privy Council, surmising that this would only hinder progress towards an accommodation with Smith. Beadle remained a Privy Counsellor for the rest of his life.

Later years

In May 1973 Beadle chaired the High Court appeal hearing for Peter Niesewand, a freelance reporter for the overseas press who had been convicted of espionage under the Official Secrets Act, prompting outcry abroad.; ; . Niesewand had written three articles in November 1972 claiming to describe the Rhodesian military's plans for combating communist-backed black nationalist guerrillas, and had been sentenced by a magistrate to two years' hard labour, one year suspended. Beadle, Goldin and Macdonald rejected the state prosecution and unanimously overturned the conviction, ruling that Niesewand's reports had embarrassed the government but did not damage the Rhodesian state. "Factual evidence as opposed to opinion was never given," Beadle commented. The government promptly expelled Niesewand from Rhodesia. After Olive's death in a motor accident in 1974, Beadle married Pleasance Johnson in 1976. He retired as Chief Justice in 1977; Macdonald succeeded him. For the rest of his life, Beadle served as an acting judge in special trials where suspected insurgents were tried for terrorist offences carrying the death penalty. In March 1977 he refused to try Abel Mapane and Jotha Bango, two Botswana citizens facing arms charges, ruling that since Rhodesia and Botswana were not at war and the Rhodesian Army had crossed into Botswana to capture the accused, the court had no jurisdiction. "Were it not so it would mean this Court condoned the illegal abduction of Botswana nationals," he explained. Beadle continued to serve under the short-lived, unrecognised government ofZimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, and sometimes as Rhobabwe, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June to 12 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was p ...

, which replaced the Rhodesian republic in June 1979, and under the British interim authorities following the Lancaster House Agreement

The Lancaster House Agreement, signed on 21 December 1979, declared a ceasefire, ending the Rhodesian Bush War; and directly led to Rhodesia achieving internationally recognised independence as Zimbabwe. It required the full resumption of di ...

of December that year. Following fresh elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative ...

in February–March 1980, the UK granted independence to Zimbabwe under the leadership of Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

in April. Beadle died, aged 75, in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Dem ...

on 14 December 1980. Hugh Beadle Primary School in Bulawayo retains its name in the 21st century.

Personality and appraisal

"A short, stocky man of ruddy complexion with a toothbrush moustache," Claire Palley writes, "Beadle had a blunt manner, looking hard at all whom he encountered. His drive and enthusiasm were overwhelming, whether at work, in charitable activities, or as a courageous hunter and fisherman. He had a warm family life and many friends." According to J.R.T. Wood, Wilson "hated Beadle perhaps because Beadle was clever but spoke his mind"; the British Prime Minister described Beadle to Lord Alport shortly after UDI as combining "the courage of a lion" with "the smartness of a fox". In Lord Blake's ''History of Rhodesia'', Beadle is characterised as "an irrepressible, bouncy extrovert, who does not always perceive the reaction which he causes in others."Garfield Todd

Sir Reginald Stephen Garfield Todd (13 July 1908 – 13 October 2002) was a liberal Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1953 to 1958 and later became an opponent of white minority rule in Rhodesia.

Background

Todd was born in Invercargil ...

, Premier of Southern Rhodesia from 1956 to 1958, saw Beadle as "impulsive" and "always inclined to overstate his case".

The black nationalist movement regarded Beadle as a white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

, pointing to his 1959 preventive detention ruling as evidence.

Wilson and other British figures saw him as two-faced for first supporting Gibbs, then declaring Smith's post-UDI government legal, and concluded that the judge must have always been a furtive UDI supporter, a theory that many have accepted. Wilson's private assistant Marcia Falkender

Marcia Matilda Falkender, Baroness Falkender, CBE (''née'' Field, known professionally as Marcia Williams; 10 March 1932 – 6 February 2019) was a British Labour politician, known first as the private secretary for, and then the political s ...

identified Beadle as "the villain of the piece", while Bottomley dubbed him UDI's "evil genius".

Others, including Palley, Wood and Facchini, contend that Beadle was determined to avert UDI and afterwards sincere in his search for an accommodation until he came to believe this was not possible. "Beadle accepted the rebellion when he realised that he was identifying himself with 'the code of an Empire that had ceased to exist'," Facchini concludes. "Thus, he retained his Privy Counsellorship as a vestige of the Rhodesia he had known all his life."

Palley asserts that but for UDI, "Beadle would have been remembered as a Commonwealth chief justice who upheld individual liberty".

"The thing that I've regretted most is this UDI and also I've regretted more than anything the fact that later it wasn't settled," Beadle said in 1972; "I think it could have been settled at a much earlier stage if Wilson had been a bit more reasonable."

Julian Greenfield, a close friend and colleague of Beadle, considered him "one who put service to the country first and foremost and laboured unceasingly on what he believed to be its true interests." According to Palley, Beadle's own view was similar—that "he did his best for his country in a time of difficult choices".

Notes and references

Footnotes References Journal and newspaper articles * * * * * * * * * Online sources * * Bibliography * also includes (on pp. 240–256) * * * * * * * * * * * * * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Beadle, Hugh 1905 births 1980 deaths Rhodesian lawyers Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford Royal Air Force officers British colonial army officers Chief justices of Rhodesia Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People from Harare Southern Rhodesian military personnel of World War II Zimbabwean Rhodes Scholars Rhodesian Queen's Counsel 20th-century King's Counsel Rhodesian politicians Members of the Legislative Assembly of Southern Rhodesia University of Cape Town alumni White Rhodesian people Zimbabwean expatriates in South Africa Knights Bachelor Officers of the Order of the British Empire Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George