Sir Ernest Satow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Ernest Mason Satow, (30 June 1843 – 26 August 1929), was a British

Ernest Satow is probably best known as the author of the book ''A Diplomat in Japan'' (based mainly on his diaries) which describes the years 1862–1869 when Japan was changing from rule by the

Ernest Satow is probably best known as the author of the book ''A Diplomat in Japan'' (based mainly on his diaries) which describes the years 1862–1869 when Japan was changing from rule by the

here

had been signed, and Satow was able to observe at first hand the steady build-up of the Japanese army and navy to avenge the humiliation by Russia, Germany and France in the

signed the protocol for Britain on 7 September 1901

He received the Knight Grand Cross of the

Satow was never able, as a diplomat serving in Japan, to marry his Japanese common-law wife, Takeda Kane 武田兼 (1853–1932) whom he met at an unknown date. They had an unnamed daughter who was born and died in infancy in 1872, and later two sons in 1880 and 1883, Eitaro and Hisayoshi. "Eitaro was diagnosed with TB in London in 1900, and was advised to go and live in the United States, where he died some time before his father. (1925-29)."

Satow's second son,

Satow was never able, as a diplomat serving in Japan, to marry his Japanese common-law wife, Takeda Kane 武田兼 (1853–1932) whom he met at an unknown date. They had an unnamed daughter who was born and died in infancy in 1872, and later two sons in 1880 and 1883, Eitaro and Hisayoshi. "Eitaro was diagnosed with TB in London in 1900, and was advised to go and live in the United States, where he died some time before his father. (1925-29)."

Satow's second son,

Collected Works of Ernest Mason Satow Part One: Major Works

1998 (includes two works not published by Satow)

2001 * 'British Policy', a series of three untitled articles written by Satow (anonymously) in the ''Japan Times'' (ed. Charles Rickerby), dated 16 March, 4 May (? date uncertain) and 19 May 1866 which apparently influenced many Japanese once it was translated and widely distributed under the title ''Eikoku sakuron'' (British policy), and probably helped to hasten the

Translated into Japanese

) *''Korea and Manchuria between Russia and Japan 1895–1904: the observations of Sir Ernest Satow, British Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan (1895–1900) and China (1900-1906)'', Selected and edited with a historical introduction, by George Alexander Lensen. – Sophia University in cooperation with Diplomatic Press, 1966 o ISBN*''A Diplomat in Siam'' by Ernest Satow C.M.G., Introduced and edited by Nigel Brailey (Orchid Press, Bangkok, reprinted 2002) * ''The Satow Siam Papers: The Private Diaries and Correspondence of Ernest Satow'', edited by Nigel Brailey (Volume 1, 1884–85), Bangkok: The Historical Society, 1997 *''The Rt. Hon. Sir Ernest Mason Satow G.C.M.G.: A Memoir'', by Bernard M. Allen (1933) * ''Satow'', by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomatic Theory from Machievelli to Kissinger'' (Palgrave, Basingstoke and New York, 2001) * '' "Not Proficient in Table-Thumping": Sir Ernest Satow at Peking, 1900–1906'' by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 161–200 * '' "A Manual of Diplomacy": The Genesis of Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice'' by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 229–243

''Diplomacy and Statecraft'', Volume 13, Number 2

includes a special section on Satow by various contributors (June, 2002) *Entry on Satow in the new

''A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds.''

Cambridge:

OCLC 50694793

* Nish, Ian. (2004). ''British Envoys in Japan 1859-1972.'' Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental.

OCLC 249167170

* Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). ''Japan Encyclopedia.'' Cambridge:

OCLC 48943301

SATOW, Rt Hon. Sir Ernest Mason

Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, accessed 11 Sept 2012

Asiatic Society of Japan

* ttps://ianruxton.wixsite.com/ernestsatow Ian Ruxton's Ernest Satow page* UK in Japan

Chronology of Heads of Mission

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Satow, Ernest Mason 1843 births 1929 deaths Alumni of University College London Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Thailand Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Uruguay Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Morocco Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Japan Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to China British expatriates in Japan British people of the Boxer Rebellion Japanese–English translators British orientalists British Japanologists English people of Swedish descent English people of German descent Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George 19th century in Japan Meiji Restoration Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Delegates to the Hague Peace Conferences People educated at Mill Hill School People from Upper Clapton British diplomats in East Asia British people of Sorbian descent Scholars of diplomacy 19th-century British diplomats 20th-century British diplomats

scholar

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researche ...

, diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or interna ...

and Japanologist

Japanese studies ( Japanese: ) or Japan studies (sometimes Japanology in Europe), is a sub-field of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on Japan. It incorporates fields such as the study of Japanes ...

.

Satow is better known in Japan than in Britain or the other countries in which he served, where he was known as . He was a key figure in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

and Anglo-Japanese relations, particularly in Bakumatsu

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji governm ...

(1853–1867) and Meiji-period (1868–1912) Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, and in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

after the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

, 1900–06. He also served in Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, and represented Britain at the Second Hague Peace Conference

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amon ...

in 1907. In his retirement he wrote ''A Guide to Diplomatic Practice'', now known as 'Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice' – this manual is widely used today, and has been updated several times by distinguished diplomats, notably Lord Gore-Booth. The sixth edition edited by Sir Ivor Roberts was published by Oxford University Press in 2009, and is over 700 pages long.

Background

Satow was born to an ethnically German father (Hans David Christoph Satow, born inWismar

Wismar (; Low German: ''Wismer''), officially the Hanseatic City of Wismar (''Hansestadt Wismar'') is, with around 43,000 inhabitants, the sixth-largest city of the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, and the fourth-largest cit ...

, then under Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

rule, naturalised British in 1846) and an English mother (Margaret, née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Mason) in Clapton, North London. He was educated at Mill Hill School

Mill Hill School is a 13–18 mixed independent, day and boarding school in Mill Hill, London, England that was established in 1807. It is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference.

History

A committee of Nonconformis ...

and University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

(UCL).

Satow was an exceptional linguist, an energetic traveller, a writer of travel guidebooks, a dictionary compiler, a mountaineer, a keen botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

(chiefly with Frederick Dickins) and a major collector of Japanese books and manuscripts on all kinds of subjects. He also loved classical music and the works of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ' ...

, on which his brother-in-law Henry Fanshawe Tozer

The Reverend Henry Fanshawe Tozer, FBA (18 May 1829 – 2 June 1916) was a British writer, teacher, traveller, and geographer. His 1897 ''History of Ancient Geography'' was well-regarded.

Biography

Tozer was born in Plymouth, Devon, the eldes ...

was an authority. Satow kept a diary for most of his adult life which amounts to 47 mostly handwritten volumes.

Satow's diplomatic career

Japan (1862–1883)

Ernest Satow is probably best known as the author of the book ''A Diplomat in Japan'' (based mainly on his diaries) which describes the years 1862–1869 when Japan was changing from rule by the

Ernest Satow is probably best known as the author of the book ''A Diplomat in Japan'' (based mainly on his diaries) which describes the years 1862–1869 when Japan was changing from rule by the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

to the restoration of Imperial rule. He was recruited by the Foreign Office straight out of university in London. Within a week of his arrival by way of China as a young student interpreter in the British Japan Consular Service

Britain had a functioning consular service in Japan from 1859 after the signing of the 1858 Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce between James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin and the Tokugawa Shogunate until 1941 when Japan invaded British colon ...

, at age 19, the Namamugi Incident

The , also known as the Kanagawa incident and Richardson affair, was a political crisis that occurred in the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan during the ''Bakumatsu'' on 14 September 1862. Charles Lennox Richardson, a British merchant, was killed by t ...

(Namamugi Jiken), in which a British merchant was killed on the Tōkaidō, took place on 21 August 1862. Satow was on board one of the British ships which sailed to Kagoshima

, abbreviated to , is the capital city of Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Located at the southwestern tip of the island of Kyushu, Kagoshima is the largest city in the prefecture by some margin. It has been nicknamed the "Naples of the Eastern wor ...

in August 1863 to obtain the compensation demanded from the Satsuma clan's ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominall ...

'', Shimazu Hisamitsu, for the slaying of Charles Lennox Richardson

Charles Lennox Richardson (16 April 1834 – 14 September 1862) was a British merchant based in Shanghai who was killed in Japan during the Namamugi Incident. His middle name is spelled ''Lenox'' in census and family documents.

Merchant

Richards ...

. They were fired on by the Satsuma shore batteries and retaliated by bombarding Kagoshima.

In 1864, Satow was with the allied force (Britain, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

) which attacked Shimonoseki

is a city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. With a population of 265,684, it is the largest city in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the fifth-largest city in the Chūgoku region. It is located at the southwestern tip of Honshu facing the Tsush ...

to enforce the right of passage of foreign ships through the narrow Kanmon Straits

The or the Straits of Shimonoseki is the stretch of water separating Honshu and Kyushu, two of Japan's four main islands. On the Honshu side of the strait is Shimonoseki (, which contributed "Kan" () to the name of the strait) and on the Kyushu ...

between Honshū and Kyūshū. Satow met Itō Hirobumi

was a Japanese politician and statesman who served as the first Prime Minister of Japan. He was also a leading member of the '' genrō'', a group of senior statesmen that dictated Japanese policy during the Meiji era.

A London-educated sa ...

and Inoue Kaoru

Marquess Inoue Kaoru (井上 馨, January 16, 1836 – September 1, 1915) was a Japanese politician and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy during the Meiji period of the Empire of Japan. As one of the senior statesmen ('' Genrō'') in J ...

of Chōshū for the first time just before the bombardment of Shimonoseki

The refers to a series of military engagements in 1863 and 1864, fought to control the Shimonoseki Straits of Japan by joint naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States, against the Japanese feudal domain of ...

. He also had links with many other Japanese leaders, including Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Sats ...

of Satsuma (who became a friend), and toured the hinterland of Japan with A. B. Mitford and, the cartoonist and illustrator, Charles Wirgman

Charles Wirgman (31 August 1832 - 8 February 1891) was an English artist and cartoonist, the creator of the ''Japan Punch'' and illustrator in China and Meiji period-Japan for the ''Illustrated London News''.

Wirgman was the eldest son of Ferdi ...

.

Satow's rise in the consular service was due at first to his competence and zeal as an interpreter at a time when English was virtually unknown in Japan, the Japanese government still communicated with the West in Dutch and available study aids were exceptionally few. Employed as a consular interpreter alongside Russell Robertson, Satow became a student of Rev. Samuel Robbins Brown

Rev. Samuel Robbins Brown D.D. (June 16, 1810 – June 20, 1880) was an American missionary to China and Japan with the Reformed Church in America.

Birth and education

Brown was born in East Windsor, Connecticut. He graduated from Yale College ...

, and an associate of Dr. James Curtis Hepburn

James Curtis Hepburn (; March 13, 1815 – September 21, 1911) was an American physician, translator, educator, and lay Christian missionary. He is known for the Hepburn romanization system for transliteration of the Japanese language into th ...

, two noted pioneers in the study of the Japanese language. His Japanese language skills quickly became indispensable in the British Minister Sir Harry Parkes's negotiations with the failing Tokugawa shogunate and the powerful Satsuma and Chōshū clans, and the gathering of intelligence. He was promoted to full Interpreter and then Japanese Secretary to the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

legation, and, as early as 1864, he started to write translations and newspaper articles on subjects relating to Japan. In 1869, he went home to England on leave, returning to Japan in 1870.

Satow was one of the founding members at Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, in 1872, of the Asiatic Society of Japan

The Asiatic Society of Japan, Inc. (一般社団法人日本アジア協会” or “Ippan Shadan Hojin Nihon Ajia Kyokai”) or "ASJ" is a non-profit organization of Japanology. ASJ serves members of a general audience that have shared interests ...

whose purpose was to study the Japanese culture, history and language (i.e. Japanology

Japanese studies ( Japanese: ) or Japan studies (sometimes Japanology in Europe), is a sub-field of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on Japan. It incorporates fields such as the study of Japanes ...

) in detail. He lectured to the Society on several occasions in the 1870s, and the Transactions of the Asiatic Society contain several of his published papers. His 1874 article on Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

covering various aspects including Japanese Literature

Japanese literature throughout most of its history has been influenced by cultural contact with neighboring Asian literatures, most notably China and its literature. Early texts were often written in pure Classical Chinese or , a Chinese-Japanes ...

that appeared in the New American Cyclopædia

The ''New American Cyclopædia'' was an encyclopedia created and published by D. Appleton & Company of New York in 16 volumes, which initially appeared between 1858 and 1863. Its primary editors were George Ripley and Charles Anderson Dana.

T ...

was one of the first such authentic piece written in any European languages. The Society is still thriving today.

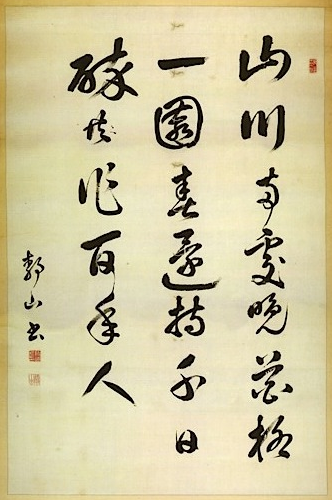

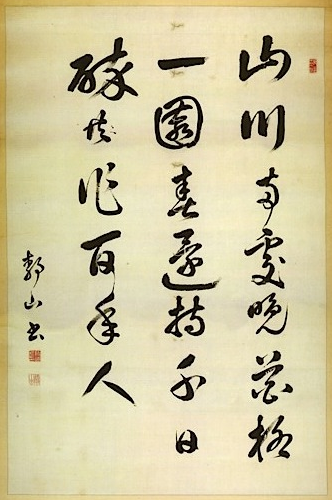

During his time in Japan, Satow devoted much effort to studying Chinese calligraphy under Kōsai Tanzan 高斎単山 (1818–1890), who gave him the artist's name Seizan 静山 in 1873. An example of Satow's calligraphy, signed as Seizan, was acquired by the British Library in 2004.

Siam, Uruguay, Morocco (1884–1895)

Satow served inSiam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

(1884–1887), during which time he was accorded the rare honour of promotion from the Consular to the Diplomatic service

Diplomatic service is the body of diplomats and foreign policy officers maintained by the government of a country to communicate with the governments of other countries. Diplomatic personnel obtains diplomatic immunity when they are accredited to o ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

(1889–93) and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

(1893–95). (Such promotion was extraordinary because the British Consular and Diplomatic services were segregated until the mid-20th century, and Satow did not come from the aristocratic class to which the Diplomatic Service was restricted.)

Japan (1895–1900)

Satow returned to Japan asEnvoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under the ...

on 28 July 1895. He stayed in Tokyo for five years (though he was on leave in London for Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

's Diamond Jubilee in 1897 and met her in August at Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in ...

, Isle of Wight). On 17 April 1895 the Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

(texhere

had been signed, and Satow was able to observe at first hand the steady build-up of the Japanese army and navy to avenge the humiliation by Russia, Germany and France in the

Triple Intervention

The Tripartite Intervention or was a diplomatic intervention by Russia, Germany, and France on 23 April 1895 over the harsh terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki imposed by Japan on the Qing dynasty of China that ended the First Sino-Japanese War. ...

of 23 April 1895. He was also in a position to oversee the transition to the ending of extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cl ...

in Japan which finally ended in 1899, as agreed by the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation

The signed by Britain and Japan, on 16 July 1894, was a breakthrough agreement; it heralded the end of the unequal treaties and the system of extraterritoriality in Japan. The treaty came into force on 17 July 1899.

From that date British subje ...

signed in London on 16 July 1894.

On Satow's personal recommendation, Hiram Shaw Wilkinson

Sir Hiram Shaw Wilkinson, JP, DL (1840–1926) was a leading British judge and diplomat, serving in China and Japan. His last position before retirement was as Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Corea.

Early life

Hira ...

, who had been a student interpreter in Japan 2 years after Satow, was appointed first, Judge of the British Court for Japan

The British Court for Japan (formally Her Britannic Majesty's Court for Japan) was a court established in Yokohama in 1879 to try cases against British subjects in Japan, under the principles of extraterritoriality. The court also heard appeals ...

in 1897 and in 1900 Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Corea

The British Supreme Court for China (originally the British Supreme Court for China and Japan) was a court established in the Shanghai International Settlement to try cases against British subjects in China, Japan and Korea under the principl ...

.

Satow built a house at Lake Chūzenji in 1896 and went there frequently to relax and escape from the pressures of his work in Tokyo.

Satow did not have the good fortune to be named the first British Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or s ...

to Japan - the honour was instead bestowed on his successor Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald

Colonel Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald, (12 June 1852 – 10 September 1915) was a British soldier and diplomat, best known for his service in China and Japan.

Early life

MacDonald was born the son of Mary Ellen MacDonald (''nee'' Dougan) and Ma ...

in 1905.

China (1900–1906)

Satow served as the British High Commissioner (September 1900 – January 1902) and then Minister inPeking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

from 1902–1906. He was active as plenipotentiary in the negotiations to conclude the Boxer Protocol

The Boxer Protocol was signed on September 7, 1901, between the Qing Empire of China and the Eight-Nation Alliance that had provided military forces (including Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, Russia, and the Un ...

which settled the compensation claims of the Powers after the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

, and hsigned the protocol for Britain on 7 September 1901

He received the Knight Grand Cross of the

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(GCMG) in the 1902 Coronation Honours

The 1902 Coronation Honours were announced on 26 June 1902, the date originally set for the coronation of King Edward VII. The coronation was postponed because the King had been taken ill two days before, but he ordered that the honours list shou ...

list. From December 1902 until summer 1903 he was on leave back home in England, during which he received the Grand Cross in person from King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second chil ...

. Satow also observed the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

(1904–1905) from his Peking post. He signed the Convention Between Great Britain and China.

Retirement (1906–1929)

In 1906 Satow was made aPrivy Councillor

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

. In 1907 he was Britain's second plenipotentiary at the Second Hague Peace Conference

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amon ...

.

In retirement (1906–1929) at Ottery St Mary

Ottery St Mary, known as "Ottery", is a town and civil parish in the East Devon district of Devon, England, on the River Otter, about east of Exeter on the B3174. At the 2001 census, the parish, which includes the villages of Metcombe, F ...

in Devon, England, he wrote mainly on subjects connected with diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. ...

and international law. In Britain, he is less well known than in Japan, where he is recognised as perhaps the most important foreign observer in the Bakumatsu and Meiji periods. He gave the Rede lecture at Cambridge University in 1908 on the career of Count Joseph Alexander Hübner

Joseph Alexander, count Hübner (26 November 1811 – 30 July 1892) was an Austrian diplomat.

Early life

Hübner was born as ''Josef Hafenbredl'' in Vienna, Austria 26 November 1811. He was the illegitimate son of Elizabeth Hafenbredl and had t ...

. It was titled ''An Austrian Diplomat in the Fifties''. Satow chose this subject with discretion to avoid censure from the British Foreign Office for discussing his own career.

As the years passed, Satow's understanding and appreciation of the Japanese evolved and deepened. For example, one of his diary entries from the early 1860s asserts that the submissive character of the Japanese will make it easy for foreigners to govern them after the "samurai problem" could be resolved; but in retirement, he wrote: "... looking back now in 1919, it seems perfectly ludicrous that such a notion should have been entertained, even as a joke, for a single moment, by anyone who understood the Japanese spirit."

Satow's extensive diaries and letters (the Satow Papers, PRO 30/33 1-23) are kept at the Public Record Office

The Public Record Office (abbreviated as PRO, pronounced as three letters and referred to as ''the'' PRO), Chancery Lane in the City of London, was the guardian of the national archives of the United Kingdom from 1838 until 2003, when it was ...

at Kew, West London in accordance with his last will and testament. His letters to Geoffrey Drage

Geoffrey Drage (17 August 1860 – 7 March 1955) was an English writer and Conservative Party politician. He was concerned particularly with the problems of the poor.

Early life and family

Drage was the son of Dr Charles Drage (1825–1922) ...

, sometime MP, are held in the Library and Archives of Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniq ...

. Many of his rare Japanese books are now part of the Oriental collection of Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

and his collection of Japanese prints are in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

He died on 26 August 1929 at Ottery St Mary, and is buried in the graveyard of St Mary's Church, Ottery St Mary

St Mary's Church is a Grade I listed building, a parish church in the Church of England in Ottery St Mary, Devon.

The church is part of "Churches Together in Ottery St Mary" which includes the churches of four other denominations in the town.

Hi ...

.

Family

Satow was never able, as a diplomat serving in Japan, to marry his Japanese common-law wife, Takeda Kane 武田兼 (1853–1932) whom he met at an unknown date. They had an unnamed daughter who was born and died in infancy in 1872, and later two sons in 1880 and 1883, Eitaro and Hisayoshi. "Eitaro was diagnosed with TB in London in 1900, and was advised to go and live in the United States, where he died some time before his father. (1925-29)."

Satow's second son,

Satow was never able, as a diplomat serving in Japan, to marry his Japanese common-law wife, Takeda Kane 武田兼 (1853–1932) whom he met at an unknown date. They had an unnamed daughter who was born and died in infancy in 1872, and later two sons in 1880 and 1883, Eitaro and Hisayoshi. "Eitaro was diagnosed with TB in London in 1900, and was advised to go and live in the United States, where he died some time before his father. (1925-29)."

Satow's second son, Takeda Hisayoshi

Hisayoshi Takeda

was a Japanese botanist whose father was the British diplomat Sir Ernest Satow. He was a founder of the Japanese Natural History Society, and is known for his campaign to preserve the environment at Oze, which is now Oze Nation ...

, became a noted botanist, founder of the Japan Natural History Society and from 1948 to 1951 was President of the Japan Alpine Club. He studied at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,100 ...

and at Birmingham University

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

. A memorial hall to him is in the Oze marshlands in Hinoemata, Fukushima Prefecture

Fukushima Prefecture (; ja, 福島県, Fukushima-ken, ) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu. Fukushima Prefecture has a population of 1,810,286 () and has a geographic area of . Fukushima Prefecture borders Miyagi ...

.

The Takeda family letters, including many of Satow's to and from his family, have been deposited at the Yokohama Archives of History

The in Naka ward, central Yokohama, near Yamashita Park, is a repository for archive materials on Japan and its connection with foreign powers since the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853. The archives are next to Kaiko Hiroba (Port ...

(formerly the British consulate in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

) at the request of Satow's granddaughters.

Selected works

* ''A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan'', by Ernest Mason Satow and A G S lbert George SidneyHawes ** ''A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan: Being a guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka and other cities; the most interesting parts of the main island between Kōbe and Awomori, with ascents of the principal mountains, and descriptions of temples, historical notes and legends with maps and plans.'' Yokohama: Kelly & Co.; Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh; Hong Kong: Kelly & Walsh, 1881. ** ''A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan: Being a guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka, Hakodate, Nagasaki, and other cities; the most interesting parts of the main island; ascents of the principal mountains; descriptions of temples; and historical notes and legends.'' London: John Murray, 1884. * ''A Guide to Diplomatic Practice'' by Sir E. Satow, (Longmans, Green & Co. London & New York, 1917). A standard reference work used in many embassies across the world, and described bySir Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, diplomat, historian, biographer, diarist, novelist, lecturer, journalist, broadcaster, and gardener. His wife was the writer Vita Sackville-West.

Early lif ...

in his book ''Diplomacy'' as "The standard work on diplomatic practice", and "admirable".Nicolson, Harold. (1963). ''Diplomacy,'' 3rd ed., p. 148. Sixth edition, edited by Sir Ivor Roberts (2009, ).

* ''A Diplomat in Japan'' by Sir E. Satow, first published by Seeley, Service & Co., London, 1921, reprinted in paperback by Tuttle, 2002. (Page numbers are slightly different in the two editions.)

* ''The Voyage of John Saris,'' ed. by Sir E. M. Satow (Hakluyt Society, 1900)

* ''The Family Chronicle of the English Satows'', by Ernest Satow, privately printed, Oxford 1925.

Collected Works of Ernest Mason Satow Part One: Major Works

1998 (includes two works not published by Satow)

2001 * 'British Policy', a series of three untitled articles written by Satow (anonymously) in the ''Japan Times'' (ed. Charles Rickerby), dated 16 March, 4 May (? date uncertain) and 19 May 1866 which apparently influenced many Japanese once it was translated and widely distributed under the title ''Eikoku sakuron'' (British policy), and probably helped to hasten the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

of 1868. Satow pointed out that the British and other treaties with foreign countries had been made by the Shogun on behalf of Japan, but that the Emperor's existence had not even been mentioned, thus calling into question their validity. Satow accused the Shogun of fraud, and demanded to know who was the 'real head' of Japan and further a revision of the treaties to reflect the political reality. He later admitted in ''A Diplomat in Japan'' (p. 155 of the Tuttle reprint edition, p. 159 of the first edition) that writing the articles had been 'altogether contrary to the rules of the service' (i.e. it is inappropriate for a diplomat or consular agent to interfere in the politics of a country in which he/she is serving). [The first and third articles are reproduced on pp. 566–75 of Grace Fox, ''Britain and Japan 1858–1883'', Oxford: Clarendon Press 1969, but the second one has only been located in the Japanese translation. A retranslation from the Japanese back into English has been attempted in I. Ruxton, ''Bulletin of the Kyūshū Institute of Technology (Humanities, Social Sciences)'', No. 45, March 1997, pp. 33–41]

Books and articles based on the Satow Papers

*''The Diaries and Letters of Sir Ernest Mason Satow (1843–1929), a Scholar-Diplomat in East Asia'', edited by Ian C. Ruxton, [ dwin Mellen Press, 1998 .Translated into Japanese

) *''Korea and Manchuria between Russia and Japan 1895–1904: the observations of Sir Ernest Satow, British Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan (1895–1900) and China (1900-1906)'', Selected and edited with a historical introduction, by George Alexander Lensen. – Sophia University in cooperation with Diplomatic Press, 1966 o ISBN*''A Diplomat in Siam'' by Ernest Satow C.M.G., Introduced and edited by Nigel Brailey (Orchid Press, Bangkok, reprinted 2002) * ''The Satow Siam Papers: The Private Diaries and Correspondence of Ernest Satow'', edited by Nigel Brailey (Volume 1, 1884–85), Bangkok: The Historical Society, 1997 *''The Rt. Hon. Sir Ernest Mason Satow G.C.M.G.: A Memoir'', by Bernard M. Allen (1933) * ''Satow'', by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomatic Theory from Machievelli to Kissinger'' (Palgrave, Basingstoke and New York, 2001) * '' "Not Proficient in Table-Thumping": Sir Ernest Satow at Peking, 1900–1906'' by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 161–200 * '' "A Manual of Diplomacy": The Genesis of Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice'' by T.G. Otte in ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 229–243

Other

*''Early Japanese books in Cambridge University Library: a catalogue of the Aston, Satow, and von Siebold collections'', Nozomu Hayashi & Peter Kornicki—Cambridge University Press, 1991. – (University of Cambridge Oriental publications; 40)''Diplomacy and Statecraft'', Volume 13, Number 2

includes a special section on Satow by various contributors (June, 2002) *Entry on Satow in the new

Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

by Dr. Nigel Brailey of Bristol University

Dramatisation

On September 1992,BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream a ...

screened a two-part dramatisation of Satow's life, titled ''A Diplomat in Japan'' in the ''Timewatch

''Timewatch'' is a long-running British television series showing documentaries on historical subjects, spanning all human history. It was first broadcast on 29 September 1982 and is produced by the BBC.

The ''Timewatch'' brandname is used as a ...

'' documentary strand. Written and directed by Christopher Railing, it starred Alan Parnaby as Satow, Benjamin Whitrow

Benjamin John Whitrow (17 February 1937 – 28 September 2017) was an English actor. He was nominated for the BAFTA TV Award for Best Actor for his role as Mr Bennet in the 1995 BBC version of ''Pride and Prejudice'', and voiced the role of Fo ...

as Sir Harry Parkes, Hitomi Tanabe as Takeda Kane, Ken Teraizumi as Ito Hirobumi, Takeshi Iba as Inoue Kaoru, and Christian Burgess as Charles Wirgman.

* ''A Clash of Cultures'' (23 September 1992)

* ''Witness to a Revolution'' (30 September 1992)

See also

*List of Ambassadors from the United Kingdom to Japan

The Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Japan is the United Kingdom's foremost diplomatic representative in Japan, and is the head of the UK's diplomatic mission there.

The following is a chronological list of British heads of mission ( ministe ...

* Anglo-Japanese relations

*Anglo-Chinese relations

British Chinese (also known as Chinese British or Chinese Britons) are people of Chineseparticularly Han Chineseancestry who reside in the United Kingdom, constituting the second-largest group of Overseas Chinese in Western Europe after Franc ...

*Asiatic Society of Japan

The Asiatic Society of Japan, Inc. (一般社団法人日本アジア協会” or “Ippan Shadan Hojin Nihon Ajia Kyokai”) or "ASJ" is a non-profit organization of Japanology. ASJ serves members of a general audience that have shared interests ...

*Yokohama Archives of History

The in Naka ward, central Yokohama, near Yamashita Park, is a repository for archive materials on Japan and its connection with foreign powers since the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853. The archives are next to Kaiko Hiroba (Port ...

has copies of Satow's diaries and his private letters to his Japanese family.

* Sakoku

was the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and nearly a ...

* List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

*Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese noblewoman, concubine and later regent who effectively controlled ...

*Chōshū Five

The were members of the Chōshū han of western Japan who travelled to England in 1863 to study at University College London. The five students were the first of many successive groups of Japanese students who travelled overseas in the late Baku ...

People who knew Satow

*William George Aston

William George Aston (9 April 1841 – 22 November 1911) was an Anglo-Irish diplomat, author and scholar-expert in the language and history of Japan and Korea.

Early life

Aston was born near Derry, Ireland.Ricorso Aston, bio notes/ref> He dis ...

*Thomas Blakiston

Thomas Wright Blakiston (27 December 1832 – 15 October 1891) was an English explorer and naturalist.

Early life and career

Born in Lymington, Hampshire, Blakiston was the son of Major John Blakiston. His grandfather was Sir Matthew Blakis ...

* Edward Bickersteth

*Basil Hall Chamberlain

Basil Hall Chamberlain (18 October 1850 – 15 February 1935) was a British academic and Japanologist. He was a professor of the Japanese language at Tokyo Imperial University and one of the foremost British Japanologists active in Japan during th ...

*Ignatius Valentine Chirol

Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol (28 May 1852 – 22 October 1929) was a British journalist, prolific author, historian and diplomat.

Early life

He was the son of the Rev. Alexander Chirol and Harriet Chirol . His education was mostly in Fr ...

* Frederick Victor Dickins

*John Harington Gubbins

John Harington Gubbins (24 January 1852 – 23 February 1929) was a British linguist, consular official and diplomat. He was the father of Sir Colin McVean Gubbins.

Education

Gubbins attended Harrow School and would have gone on to Cambridge Un ...

*Nicholas John Hannen

Sir Nicholas John Hannen (24 August 1842 – 27 April 1900) was a British barrister, diplomat and judge who served in China and Japan. He was the Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Japan from 1891 to 1900 and also served c ...

* Maurice Joostens

*Joseph Henry Longford

Joseph Henry Longford (25 June 1849 in Dublin – 12 May 1925 in London) was a British consular official in the British Japan Consular Service from 24 February 1869 until 15 August 1902. He was Consul in Formosa (1895–97) after the First ...

*George Ernest Morrison

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China during the First World War and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ...

*Harry Smith Parkes

Sir Harry Smith Parkes (24 February 1828 – 22 March 1885) was a British diplomat who served as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary and Consul General of the United Kingdom to the Empire of Japan from 1865 to 1883 and the Chinese ...

*Edward Hobart Seymour

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Edward Hobart Seymour, (30 April 1840 – 2 March 1929) was a Royal Navy officer. As a junior officer he served in the Black Sea during the Crimean War. He then took part in the sinking of the war-junks, the Battle of ...

* Alexander Croft Shaw

*Harold Temperley

Harold William Vazeille Temperley, (20 April 1879 – 11 July 1939) was an English historian, Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge from 1931, and Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge.

Overview

Temperley was born in Cambridg ...

*Hiram Parkes Wilkinson

Hiram Parkes "Harrie" Wilkinson, KC (9 June 1866 – 1 April 1935) served as Crown Advocate of the British Supreme Court for China and Japan from 1897 to 1925. He was also Acting Assistant Judge of the British Court for Siam from 1903 to 1905 an ...

*Hiram Shaw Wilkinson

Sir Hiram Shaw Wilkinson, JP, DL (1840–1926) was a leading British judge and diplomat, serving in China and Japan. His last position before retirement was as Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Corea.

Early life

Hira ...

* William Willis

*Charles Wirgman

Charles Wirgman (31 August 1832 - 8 February 1891) was an English artist and cartoonist, the creator of the ''Japan Punch'' and illustrator in China and Meiji period-Japan for the ''Illustrated London News''.

Wirgman was the eldest son of Ferdi ...

*Wu Tingfang

Wu Ting-fang (; 30 July 184223 June 1922) was a diplomat and politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and briefly as Acting Premier during the early years of the Republic of China. He was also known as Ng Choy or Ng Achoy ().

Ed ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Cullen, Louis M. (2003)''A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds.''

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

. ; OCLC 50694793

* Nish, Ian. (2004). ''British Envoys in Japan 1859-1972.'' Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental.

OCLC 249167170

* Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). ''Japan Encyclopedia.'' Cambridge:

Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retir ...

. OCLC 48943301

SATOW, Rt Hon. Sir Ernest Mason

Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, accessed 11 Sept 2012

External links

* *Asiatic Society of Japan

* ttps://ianruxton.wixsite.com/ernestsatow Ian Ruxton's Ernest Satow page* UK in Japan

Chronology of Heads of Mission

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Satow, Ernest Mason 1843 births 1929 deaths Alumni of University College London Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Thailand Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Uruguay Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Morocco Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Japan Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to China British expatriates in Japan British people of the Boxer Rebellion Japanese–English translators British orientalists British Japanologists English people of Swedish descent English people of German descent Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George 19th century in Japan Meiji Restoration Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Delegates to the Hague Peace Conferences People educated at Mill Hill School People from Upper Clapton British diplomats in East Asia British people of Sorbian descent Scholars of diplomacy 19th-century British diplomats 20th-century British diplomats