Sima Qian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sima Qian (; ; ) was a Chinese historian of the early

In 99 BC, Sima became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where

In 99 BC, Sima became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where

Significance of ''Shiji'' on literature

Sima Qian: China's 'grand historian'

article by Carrie Gracie in BBC News Magazine, 7 October 2012 {{DEFAULTSORT:Sima, Qian 86 BC deaths 2nd-century BC births 2nd-century BC Chinese historians 1st-century BC Chinese historians 1st-century BC Chinese poets Ancient astrologers Chinese astrologers Chinese prisoners sentenced to death Han dynasty eunuchs Han dynasty historians Han dynasty poets Han dynasty politicians from Shaanxi Historians from Shaanxi Poets from Shaanxi Prisoners sentenced to death by China Legendary Chinese people

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(206AD220). He is considered the father of Chinese historiography for his ''Records of the Grand Historian

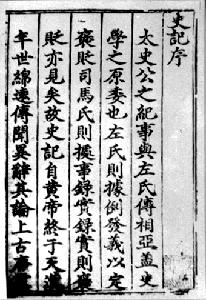

''Records of the Grand Historian'', also known by its Chinese name ''Shiji'', is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The ''Records'' was written in the early 1st century by the ancient Chinese his ...

'', a general history of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

covering more than two thousand years beginning from the rise of the legendary Yellow Emperor

The Yellow Emperor, also known as the Yellow Thearch or by his Chinese name Huangdi (), is a deity ('' shen'') in Chinese religion, one of the legendary Chinese sovereigns and culture heroes included among the mytho-historical Three Soverei ...

and the formation of the first Chinese polity to the reigning sovereign of Sima Qian's time, Emperor Wu of Han. As the first universal history of the world as it was known to the ancient Chinese, the ''Records of the Grand Historian'' served as a model for official history-writing for subsequent Chinese dynasties and the Chinese cultural sphere (Korea, Vietnam, Japan) up until the 20th century.

Sima Qian's father Sima Tan

Sima Tan (; 165–110 BCE) was a Chinese astrologer and historian during the Western Han dynasty. His work ''Records of the Grand Historian'' was completed by his son Sima Qian, who is considered the founder of Chinese historiography.

Ed ...

first conceived of the ambitious project of writing a complete history of China, but had completed only some preparatory sketches at the time of his death. After inheriting his father's position as court historian in the imperial court, he was determined to fulfill his father's dying wish of composing and putting together this epic work of history. However, in 99 BC, he would fall victim to the Li Ling

Li Ling (, died 74 BC), courtesy name Shaoqing (少卿), was a Chinese military general of the Han Dynasty who served during the reign of Emperor Wu (汉武帝) and later defected to the Xiongnu after being defeated in an expedition in 99 BC.

...

affair for speaking out in defense of the general, who was blamed for an unsuccessful campaign against the Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

. Given the choice of being executed or castrated, he chose the latter in order to finish his historical work. Although he is universally remembered for the ''Records'', surviving works indicate that he was also a gifted poet and prose writer, and he was instrumental in the creation of the ''Taichu'' calendar, which was officially promulgated in 104 BC.

As his position in the imperial court was "Grand Historian" (''tàishǐ'' , variously translated as court historian, scribe, or astronomer/astrologer), later generations would accord him with the honorific title of "Lord Grand Historian" (''Tàishǐ Gōng'' ) for his monumental work, though his ''magnum opus'' was completed many years after his tenure as Grand Historian ended in disgrace and after his acceptance of punitive actions against him, including imprisonment, castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharma ...

, and subjection to servility. He was acutely aware of the importance of his work to posterity and its relationship to his own personal suffering. In the postface of the ''Records'', he implicitly compared his universal history of China to the classics of his day, the '' Guoyu'' by Zuoqiu Ming'', Lisao'' by Qu Yuan

Qu Yuan ( – 278 BCE) was a Chinese poet and politician in the State of Chu during the Warring States period. He is known for his patriotism and contributions to classical poetry and verses, especially through the poems of the '' ...

, and the ''Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is comp ...

'' by Sun Bin

Sun Bin (died 316 BC) was a Chinese general, military strategist, and writer who lived during the Warring States period of Chinese history. A supposed descendant of Sun Tzu, Sun was tutored in military strategy by the hermit Guiguzi. He w ...

, pointing out that their authors all suffered great personal misfortunes before their lasting monumental works could come to fruition. Sima Qian is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu

''Wu Shuang Pu'' () is a book of woodcut prints, first printed in 1694, early on in the Qing dynasty. This book contains the biographies and imagined portraits of 40 notable heroes and heroines from the Han Dynasty to the Song Dynasty, all acco ...

(無雙譜, Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Early life and education

Sima Qian was born at Xiayang inZuopingyi

Pingyi ( zh, 馮翊), also known as Zuo Pingyi ( zh, 左馮翊), was a historical region of China located in modern Shaanxi province.

In early Han dynasty, the administrator of an area to the east of the capital Chang'an was known as ''Zuo Neishi' ...

(around present-day Hancheng

Hancheng () is a city in Shaanxi Province, People's Republic of China, about 125 miles northeast of Xi'an, at the point where the south-flowing Yellow River enters the Guanzhong Plain. It is a renowned historic city, containing numerous historic ...

, Shaanxi Province

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), Ni ...

). He was most likely born about 145, though some sources say he was born about 135. Around 136, his father, Sima Tan

Sima Tan (; 165–110 BCE) was a Chinese astrologer and historian during the Western Han dynasty. His work ''Records of the Grand Historian'' was completed by his son Sima Qian, who is considered the founder of Chinese historiography.

Ed ...

, received an appointment to the position of "grand historian" (''tàishǐ'' , alt. "grand scribe" or "grand astrologer"). The grand historian position was relatively low-ranking, and its primary duty was to formulate the yearly calendar, identifying which days were ritually auspicious or inauspicious, and present it to the emperor prior to New Year's Day. The grand historian's other duties included traveling with the emperor for important rituals and recording daily events both at the court and around the country. By his account, by the age of ten Sima was able to "read the old writings" and was considered to be a promising scholar. Sima grew up in a Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

environment, and Sima always regarded his historical work as an act of Confucian filial piety to his father.

In 126, around the age of twenty, Sima Qian began an extensive tour around China as it existed in the Han dynasty. He started his journey from the imperial capital, Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

(near modern Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

), then went south across the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

to

Changsha Kingdom

The Changsha Kingdom was a kingdom within the Han Empire of China, located in present-day Hunan and some surrounding areas. The kingdom was founded when Emperor Gaozu granted the territory to his follower Wu Rui in 203 or 202 BC, around the sa ...

(modern Hunan Province), where he visited the Miluo River

The Miluo River (, and with modified Wade–Giles using the form Mi-lo) is located on the eastern bank of Dongting Lake, the largest tributary of the Xiang River in the northern Hunan Province. It is an important river in the Dongting Lake watershe ...

site where the Warring States

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

era poet Qu Yuan

Qu Yuan ( – 278 BCE) was a Chinese poet and politician in the State of Chu during the Warring States period. He is known for his patriotism and contributions to classical poetry and verses, especially through the poems of the '' ...

was traditionally said to have drowned himself. He then went to seek the burial place of the legendary rulers Yu on Mount Kuaiji

Mount Xianglu () is a mountain near Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China. Its summit has an elevation of .

History

Its historic name was Mount Kuaiji (), formerly romanized as Mount K'uai-chi It was an important site for ancient China's Yue civilization a ...

and Shun

Shun may refer to one of the following:

*To shun, which means avoiding association with an individual or group

* Shun (given name), a masculine Japanese given name

*Seasonality in Japanese cuisine (''shun'', 旬)

Emperor Shun

* Emperor Shun (� ...

in the Jiuyi Mountains

The Jiuyi Mountains ( ''Jiuyi Shan'') are a mountain range in Hunan province, China. They are located in the Yongzhou, Ningyuan County, Ningyuan and Lanshan County, Lanshan region, bordering Guangdong province.

They are part of the Mengzhu Mountai ...

(modern Ningyuan County

Ningyuan County () is a county of Hunan Province, China, it is under the administration of Yongzhou prefecture-level City. also see

Located on the southern part of the province, the county is bordered to the north by Qiyang County, to the north ...

, Hunan). He then went north to Huaiyin (modern Huai'an

Huai'an (), formerly called Huaiyin () until 2001, is a prefecture-level city in the central part of Jiangsu province in East China, Eastern China. Huai'an is situated almost directly south of Lianyungang, southeast of Suqian, northwest of Yan ...

, Jiangsu Province) to see the grave of Han dynasty general Han Xin

Han Xin (; 231/230–196 BC) was a Chinese military general and politician who served Liu Bang during the Chu–Han Contention and contributed greatly to the founding of the Han dynasty. Han Xin was named as one of the "Three Heroes of the ea ...

, then continued north to Qufu

Qufu ( ; ) is a city in southwestern Shandong province, East China. It is located about south of the provincial capital Jinan and northeast of the prefectural seat at Jining. Qufu has an area of 815 square kilometers, and a total population of ...

, the hometown of Confucius

Confucius ( ; zh, s=, p=Kǒng Fūzǐ, "Master Kǒng"; or commonly zh, s=, p=Kǒngzǐ, labels=no; – ) was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. C ...

, where he studied ritual and other traditional subjects.

As Han court official

After his travels, Sima was chosen to be a Palace Attendant in the government, whose duties were to inspect different parts of the country with Emperor Wu in 122 BC. Sima married young and had one daughter. In 110 BC, at the age of thirty-five, Sima Qian was sent westward on a military expedition against some "barbarian" tribes. That year, his father fell ill due to the distress of not being invited to attend the Imperial Feng Sacrifice. Suspecting his time was running out, he summoned his son back home to take over the historical work he had begun. Sima Tan wanted to follow the ''Annals of Spring and Autumn

The ''Spring and Autumn Annals'' () is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The ''Annals'' is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 241-year period from 722 to 481 ...

''—the first chronicle in the history of Chinese literature. It appears that Sima Tan was only able to put together an outline of the work before he died. the postface of the completed ''Shiji'', there is a short essay on the six philosophical schools that is explicitly attributed to Sima Tan. Otherwise, there are only fragments of the ''Shiji'' that are speculated to be authored by Sima Tan or based on his notes. Fueled by his father's inspiration, Sima Qian spent much of the subsequent decade authoring and compiling the ''Records of the Grand Historian

''Records of the Grand Historian'', also known by its Chinese name ''Shiji'', is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The ''Records'' was written in the early 1st century by the ancient Chinese his ...

'', completing it before 91 BC, probably around 94 BC. Three years after the death of his father, Sima Qian assumed his father's previous position as ''taishi''. In 105 BC, Sima was among the scholars chosen to reform the calendar. As a senior imperial official, Sima was also in the position to offer counsel to the emperor on general affairs of state.

The Li Ling affair

In 99 BC, Sima became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where

In 99 BC, Sima became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where Li Ling

Li Ling (, died 74 BC), courtesy name Shaoqing (少卿), was a Chinese military general of the Han Dynasty who served during the reign of Emperor Wu (汉武帝) and later defected to the Xiongnu after being defeated in an expedition in 99 BC.

...

and Li Guangli

Li Guangli (died 88 BC) was a Chinese military general of the Western Han dynasty and a member of the Li family favoured by Emperor Wu of Han. His brother Li Yannian was also close to Emperor Wu. With the suicide of Emperor Wu's crown prince Li ...

, two military officers who led a campaign against the Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

in the north, were defeated and taken captive. Emperor Wu attributed the defeat to Li Ling, with all government officials subsequently condemning him for it. Sima was the only person to defend Li Ling, who had never been his friend but whom he respected. Emperor Wu interpreted Sima's defence of Li as an attack on his brother-in-law, Li Guangli, who had also fought against the Xiongnu without much success, and sentenced Sima to death. At that time, execution could be commuted either by money or castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharma ...

. Since Sima did not have enough money to atone his "crime", he chose the latter and was then thrown into prison, where he endured three years. He described his pain thus: "When you see the jailer you abjectly touch the ground with your forehead. At the mere sight of his underlings you are seized with terror ... Such ignominy can never be wiped away." Sima called his castration "the worst of all punishments".

In 96 BC, on his release from prison, Sima chose to live on as a palace eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

to complete his histories, rather than commit suicide as was expected of a gentleman-scholar who had been disgraced by being castrated. As Sima Qian himself explained in his ''Letter to Ren An'':

Later years and death

Upon his release from prison in 97/96 BC, Sima Qian continued to serve in the Han court as ''zhongshuling'' ( 中書令), a court archivist position reserved for eunuchs with considerable status and with higher pay than his previous position of historian. The ''Letter to Ren An'' was written by Sima Qian in reply to Ren An in response to the latter's involvement in Crown Prince Liu Ju's rebellion in 91 BC. This is the last record of Sima Qian in contemporary documents. The letter is a reply to a lost letter by Ren An to Sima Qian, perhaps asking Sima Qian to intercede on his behalf as Ren An was facing execution for accusations of being an opportunist and displaying equivocal loyalty to the emperor during the rebellion. In his reply, Sima Qian stated that he is a mutilated man with no influence at court. Some later historians claimed that Sima Qian himself became implicated in the rebellion as a result of his friendship with Ren An and was executed as part of the purge of the crown prince's supporters in court; however, the earliest attested record of this account dates from the 4th century. Moreover, it has also been pointed out that Sima Qian would have been reluctant to render substantive aid to Ren An, given the severe consequences that he suffered for supporting General Li Ling, as well as Ren An's failure to act on his behalf during the Li Ling affair. Although there are many theories regarding the exact dating as well as the true nature and purpose of the ''Letter to Ren An'', one common interpretation suggests that the letter, in part, tacitly expressed a refusal to play an active role in securing a reduced punishment for Ren An. The early 20th century scholarWang Guowei

Wang Guowei (; 2 December 18772 June 1927) or Wang Kuo-wei, courtesy name Jing'an () or Boyu (), was a Chinese historian and poet. A versatile and original scholar, he made important contributions to the studies of ancient history, epigraphy, ph ...

stated that there are no reliable records establishing when Sima Qian died. He and most modern historians believe that Sima Qian spent his last days as a scholar in reclusion () after leaving the Han court, perhaps dying around the same time as Emperor Wu in 87/86 BC.

''Records of the Grand Historian''

Format

Although the style and form of Chinese historical writings varied through the ages, ''Records of the Grand Historian'' (''Shiji'') has defined the quality and style from then onwards. Before Sima, histories were written as certain events or certain periods of history of states; his idea of a general history affected later historiographers like Zheng Qiao (鄭樵) in writing '' Tongzhi'' andSima Guang

Sima Guang (17 November 1019 – 11 October 1086), courtesy name Junshi, was a Chinese historian, politician, and writer. He was a high-ranking Song dynasty scholar-official who authored the monumental history book ''Zizhi Tongjian''. Sima was ...

in writing ''Zizhi Tongjian

''Zizhi Tongjian'' () is a pioneering reference work in Chinese historiography, published in 1084 AD during the Northern Song (960–1127), Northern Song dynasty in the form of a chronicle recording Chinese history from 403 BC to 959&n ...

''. The Chinese historical form of dynasty history, or ''jizhuanti'' history of dynasties, was codified in the second dynastic history by Ban Gu's ''Book of Han

The ''Book of Han'' or ''History of the Former Han'' (Qián Hàn Shū,《前汉书》) is a history of China finished in 111AD, covering the Western, or Former Han dynasty from the first emperor in 206 BCE to the fall of Wang Mang in 23 CE. ...

'', but historians regard Sima's work as their model, which stands as the "official format" of the history of China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

. The ''Shiji'' comprises 130 chapters consisting of half a million characters.

The ''jizhuanti'' format refers to the organization of the work into ''benji'' (本紀) or 'basic annals' chapters containing the biographies of the sovereigns ('sons of heaven') organized by dynasty and ''liezhuan'' (列傳) or 'ordered biographies' chapters containing the biographies of influential non-nobles, sometimes for one prominent individual, but often for two or more people who, in Sima Qian's judgment, played similarly important roles in history. In addition to these namesake categories, there are chapters falling under the categories of ''biao'' (表) or 'tables', containing graphical chronologies of royalty and nobility, and ''shu'' (書) or 'treatises', consisting of essays giving a historical perspective on various topics like music, ritual, or economics. Most importantly, the ''shijia'' (世家) chapters, or 'house chronicles', document important events in the histories of the rulers of each of the quasi-independent states of the Zhou dynasty (originally serving as vassals to the Zhou kings), as well as the histories of contemporary aristocratic houses established during the Han dynasty.

In all, the ''Records'' consist of 12 Basic Annals, 10 Tables, 8 Treatises, 30 House Chronicles, and 70 Ordered Biographies. The last of the Ordered Biographies is the postface. This final chapter details the background of how the ''Shiji'' was composed and compiled, and gives brief justifications for the inclusion of the major topics, events, and individuals in the work. As part of the background, the postface provides a short sketch of the history of the Sima clan, from legendary times to his father Sima Tan. It also details the dying words of Sima Tan, tearfully exhorting the author to compose the present work, and contains a biographical sketch of the author himself. The postface concludes with a self-referential description of the postface as the 70th and last of the Ordered Biographies chapters.

Influences and works influenced

Sima was greatly influenced by Confucius's ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', which on the surface is a succinct chronology from the events of the reigns of the twelve dukes of Lu from 722 to 484 BC. Many Chinese scholars have and still do view how Confucius ordered his chronology as the ideal example of how history should be written, especially with regards to what he chose to include and to exclude; and his choice of words as indicating moral judgements Seen in this light, the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'' are a moral guide to the proper way of living. Sima took this view himself as he explained: Sima saw the ''Shiji'' as being in the same tradition as he explained in his introduction to chapter 61 of the ''Shiji'' where he wrote: To resolve this theodical problem, Sima argued that while the wicked may succeed and the good may suffer in their own life-times, it is the historian who ensures that in the end good triumphs. For Sima, the writing of history was no mere antiquarian pursuit, but was rather a vital moral task as the historian would "preserve memory", and thereby ensure the ultimate victory of good over evil. Along these lines, Sima wrote: Such a moralizing approach to history with the historian high-guiding the good and evil to provide lessons for the present could be dangerous for the historian as it could bring down the wrath of the state onto the historian as happened to Sima himself. As such, the historian had to tread carefully and often expressed his judgements in a circuitous way designed to fool the censor. Sima himself in the conclusion to chapter 110 of the ''Shiji'' declared that he was writing in this tradition where he stated: Bearing this in mind, not everything that Sima wrote should be understood as conveying didactical moral lessons. But several historians have suggested that parts of the ''Shiji'', such as where Sima placed his section on Confucius's use of indirect criticism in the part of the book dealing with the Xiongnu "barbarians" might indicate his disapproval of the foreign policy of the Emperor Wu. In writing ''Shiji'', Sima initiated a new writing style by presenting history in a series of biographies. His work extends over 130 chapters—not in historical sequence, but divided into particular subjects, includingannals

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

, chronicles, and treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Tre ...

s—on music, ceremonies, calendars, religion, economics, and extended biographies. Sima's work influenced the writing style of other histories outside of China as well, such as the Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificat ...

(Korean) history the ''Samguk sagi

''Samguk Sagi'' (, ''History of the Three Kingdoms'') is a historical record of the Three Kingdoms of Korea: Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla. The ''Samguk Sagi'' is written in Classical Chinese, the written language of the literati of ancient Korea, ...

''. Sima adopted a new method in sorting out the historical data and a new approach to writing historical records. At the beginning of the ''Shiji'', Sima declared himself a follower of Confucius's approach in the ''Analects'' to "hear much but leave to one side that which is doubtful, and speak with due caution concerning the remainder". Reflecting these rigorous analytic methods, Sima declared that he would not write about periods of history where there was insufficient documentation. As such, Sima wrote "the ages before the Ch'in dynasty are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here". In the same way, Sima discounted accounts in the traditional records that were "ridiculous" such as the pretense that Prince Tan could via the use of magic make the clouds rain grain and horses grow horns. Sima constantly compared accounts found in the manuscripts with what he considered reliable sources like Confucian classics like the '' Book of Odes'', ''Book of History

The ''Book of Documents'' (''Shūjīng'', earlier ''Shu King'') or ''Classic of History'', also known as the ''Shangshu'' (“Venerated Documents”), is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetorica ...

'', ''Book of Rites

The ''Book of Rites'', also known as the ''Liji'', is a collection of texts describing the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou dynasty as they were understood in the Warring States and the early Han periods. The ''Book ...

'', '' Book of Music'', ''Book of Changes

The ''I Ching'' or ''Yi Jing'' (, ), usually translated ''Book of Changes'' or ''Classic of Changes'', is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zho ...

'' and ''Spring and Autumn Annals''. When Sima encountered a story that could not be cross-checked with the Confucian classics, he systemically compared the information with other documents. Sima mentioned at least 75 books he used for cross-checking. Furthermore, Sima often questioned people about historical events they had experienced. Sima mentioned after one of his trips across China that: "When I had occasion to pass through Feng and Beiyi I questioned the elderly people who were about the place, visited the old home of Xiao He

Xiao He (257 BC–193 BC) was a Chinese politician of the early Western Han dynasty. He served Liu Bang (Emperor Gao), the founder of the Han dynasty, during the insurrection against the Qin dynasty, and fought on Liu's side in the Chu–Han C ...

, Cao Can

Cao Shen or Cao Can (died 190 BC), courtesy name Jingbo (), was a chancellor of the Western Han dynasty. He participated in the Chu–Han Contention on Liu Bang ( Emperor Gaozu of Han)'s side and contributed greatly to the founding of the Han ...

, Fan Kuai

Fan Kuai (242–189 BC) was a military general of the early Western Han dynasty. He was a prominent figure of the Chu–Han Contention (206–202 BC), a power struggle for supremacy over China between the Han dynasty's founder, Liu Bang (Emper ...

and Xiahou Ying

Xiahou Ying (died 172 BC), posthumously known as Marquis Wen of Ruyin, was a Chinese official who served as Minister Coachman () during the early Han dynasty. He served under Liu Bang (Emperor Gaozu), the founding emperor of the Han dynasty, a ...

, and learned much about the early days. How different it was from the stories one hears!" Reflecting the traditional Chinese reverence for age, Sima stated that he preferred to interview the elderly as he believed that they were the most likely to supply him with correct and truthful information about what had happened in the past. During one of this trips, Sima mentioned that he was overcome with emotion when he saw the carriage of Confucius together with his clothes and various other personal items that had belonged to Confucius.

Innovations and unique features

Despite his very large debts to Confucian tradition, Sima was an innovator in four ways. To begin with, Sima's work was concerned with the history of the known world. Previous Chinese historians had focused on only one dynasty and/or region. Sima's history of 130 chapters began with the legendary Yellow Emperor and extended to his own time, and covered not only China, but also neighboring nations likeKorea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. In this regard, Sima was significant as the first Chinese historian to treat the peoples living to the north of the Great Wall like the Xiongnu as human beings who were implicitly the equals of the Middle Kingdom, instead of the traditional approach which had portrayed the Xiongnu as savages who had the appearance of humans, but the minds of animals. In his comments about the Xiongnu, Sima refrained from evoking claims about the innate moral superiority of the Han over the "northern barbarians" that were the standard rhetorical tropes of Chinese historians in this period. Likewise, Sima in his chapter about the Xiongnu condemns those advisors who pursue the "expediency of the moment", that is advise the Emperor to carry policies such as conquests of other nations that bring a brief moment of glory, but burden the state with the enormous financial and often human costs of holding on to the conquered land. Sima was engaging in an indirect criticism of the advisors of the Emperor Wu who were urging him to pursue a policy of aggression towards the Xiongnu and conquer all their land, a policy that Sima was apparently opposed to.

Sima also broke new ground by using more sources like interviewing witnesses, visiting places where historical occurrences had happened, and examining documents from different regions and/or times. Before Chinese historians had tended to use only reign histories as their sources. The ''Shiji'' was further very novel in Chinese historiography by examining historical events outside of the courts, providing a broader history than the traditional court-based histories had done. Lastly, Sima broke with the traditional chronological structure of Chinese history. Sima instead had divided the ''Shiji'' into five divisions: the basic annals which comprised the first 12 chapters, the chronological tables which comprised the next 10 chapters, treatises on particular subjects which make up 8 chapters, accounts of the ruling families which take up 30 chapters, and biographies of various eminent people which are the last 70 chapters. The annals follow the traditional Chinese pattern of court-based histories of the lives of various emperors and their families. The chronological tables are graphs recounting the political history of China. The treatises are essays on topics such as astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, music, religion, hydraulic engineering and economics. The last section dealing with biographies covers individuals judged by Sima to have made a major impact on the course of history, regardless of whether they were of noble or humble birth and whether they were born in the central states, the periphery, or barbarian lands. Unlike traditional Chinese historians, Sima went beyond the androcentric, nobility-focused histories by dealing with the lives of women and men such as poets, bureaucrats, merchants, comedians/jesters, assassins, and philosophers. The treatises section, the biographies sections and the annals section relating to the Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

(as a former dynasty, there was more freedom to write about the Qin than there was about the reigning Han dynasty) that make up 40% of the ''Shiji'' have aroused the most interest from historians and are the only parts of the ''Shiji'' that have been translated into English.

When Sima placed his subjects was often his way of expressing obliquely moral judgements. Empress Lü

Empress (Dowager) Lü Zhi (241–18 August 180 BC), commonly known as Empress Lü () and formally Empress Gao of Han (), was the empress consort of Gaozu, the founding emperor of the Han dynasty. They had two known children, Liu Ying (later E ...

and Xiang Yu

Xiang Yu (, –202 BC), born Xiang Ji (), was the Hegemon-King (Chinese: 霸王, ''Bà Wáng'') of Western Chu during the Chu–Han Contention period (206–202 BC) of China. A noble of the Chu state, Xiang Yu rebelled against the Qin dyna ...

were the effective rulers of China during reigns Hui of the Han and Yi of Chu, respectively, so Sima placed both their lives in the basic annals. Likewise, Confucius is included in the fourth section rather the fifth where he properly belonged as a way of showing his eminent virtue. The structure of the ''Shiji'' allowed Sima to tell the same stories in different ways, which allowed him to pass his moral judgements. For example, in the basic annals section, the Emperor Gaozu is portrayed as a good leader whereas in the section dealing with his rival Xiang Yu, the Emperor is portrayed unflatteringly. Likewise, the chapter on Xiang presents him in a favorable light whereas the chapter on Gaozu portrays him in more darker colors. At the end of most of the chapters, Sima usually wrote a commentary in which he judged how the individual lived up to traditional Chinese values like filial piety, humility, self-discipline, hard work and concern for the less fortunate. Sima analyzed the records and sorted out those that could serve the purpose of ''Shiji''. He intended to discover the patterns and principles of the development of human history. Sima also emphasized, for the first time in Chinese history, the role of individual men in affecting the historical development of China and his historical perception that a country cannot escape from the fate of growth and decay.

Unlike the ''Book of Han'', which was written under the supervision of the imperial dynasty, ''Shiji'' was a privately written history since he refused to write ''Shiji'' as an official history covering only those of high rank. The work also covers people of the lower classes and is therefore considered a "veritable record" of the darker side of the dynasty. In Sima's time, literature and history were not seen as separate disciplines as they are now, and Sima wrote his ''magnum opus'' in a very literary style, making extensive use of irony, sarcasm, juxtaposition of events, characterization, direct speech and invented speeches, which led the American historian Jennifer Jay to describe parts of the ''Shiji'' as reading more like a historical novel than a work of history. For an example, Sima tells the story of a Chinese eunuch named Zhonghang Yue Zhonghang Yue () was a eunuch from the Han dynasty who surrendered to Xiongnu (or Hun) nationality. He was selected as a retinue from Han to Hun and later served the Xiongnu emperor Laoshang Shanyu. Zhonghang Yue raised a series of theories for the ...

who became an advisor to the Xiongnu kings. Sima provides a long dialogue between Zhonghang and an envoy sent by the Emperor Wen of China during which the latter disparages the Xiongnu as "savages" whose customs are barbaric while Zhonghang defends the Xiongnu customs as either justified and/or as morally equal to Chinese customs, at times even morally superior as Zhonghang draws a contrast between the bloody succession struggles in China where family members would murder one another to be Emperor vs. the more orderly succession of the Xiongnu kings. The American historian Tamara Chin wrote that though Zhonghang did exist, the dialogue is merely a "literacy device" for Sima to make points that he could not otherwise make. The favorable picture of the traitor Zhonghang who went over to the Xiongnu who bests the Emperor's loyal envoy in an ethnographic argument about what is the morally superior nation appears to be Sima's way of attacking the entire Chinese court system where the Emperor preferred the lies told by his sycophantic advisors over the truth told by his honest advisors as inherently corrupt and depraved. The point is reinforced by the fact that Sima has Zhonghang speak the language of an idealized Confucian official whereas the Emperor's envoy's language is dismissed as "mere twittering and chatter". Elsewhere in the ''Shiji'' Sima portrayed the Xiongnu less favorably, so the debate was almost certainly more Sima's way of criticizing the Chinese court system and less genuine praise for the Xiongnu.

Sima has often been criticized for "historizing" myths and legends as he assigned dates to mythical and legendary figures from ancient Chinese history together with what appears to be suspiciously precise genealogies of leading families over the course of several millennia (including his own where he traces the descent of the Sima family from legendary emperors in the distant past). However, archaeological discoveries in recent decades have confirmed aspects of the ''Shiji'', and suggested that even if the sections of the ''Shiji'' dealing with the ancient past are not totally true, at least Sima wrote down what he believed to be true. In particular, archaeological finds have confirmed the basic accuracy of the ''Shiji'' including the reigns and locations of tombs of ancient rulers.

Literary figure

Sima's ''Shiji'' is respected as a model of biographical literature with high literary value and still stands as a textbook for the study of classical Chinese. Sima's works were influential to Chinese writing, serving as ideal models for various types of prose within the neo-classical ("renaissance" 复古) movement of theTang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

-Song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetit ...

period. The great use of characterisation and plotting also influenced fiction writing, including the classical short stories of the middle and late medieval period (Tang-Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

) as well as the vernacular novel of the late imperial period. Sima had immense influence on historiography not only in China, but also in Japan and Korea. For centuries afterwards, the ''Shiji'' was regarded as the greatest history book written in Asia. Sima is little known in the English-speaking world as a full translation of the ''Shiji'' in English has not yet been completed.

His influence was derived primarily from the following elements of his writing: his skillful depiction of historical characters using details of their speech, conversations, and actions; his innovative use of informal, humorous, and varied language; and the simplicity and conciseness of his style. Even the 20th-century literary critic Lu Xun

Zhou Shuren (25 September 1881 – 19 October 1936), better known by his pen name Lu Xun (or Lu Sun; ; Wade–Giles: Lu Hsün), was a Chinese writer, essayist, poet, and literary critic. He was a leading figure of modern Chinese literature. ...

regarded ''Shiji'' as "the historians' most perfect song, a "Li Sao

"''Li Sao''" (; translation: "Encountering Sorrow") is an ancient Chinese poem from the anthology '' Chuci'' traditionally attributed to Qu Yuan. ''Li Sao'' dates from the late 3rd century BCE, during the Chinese Warring States period.

Backgro ...

" without the rhyme" (史家之絶唱,無韻之離騷) in his ''Outline of Chinese Literary History'' (漢文學史綱要).

Other literary works

Sima's famous letter to his friend Ren An about his sufferings during the Li Ling Affair and his perseverance in writing ''Shiji'' is today regarded as a highly admired example of literary prose style, studied widely in China even today. The ''Letter to Ren An'' contains the quote, "Men have always had but one death. For some it is as weighty asMount Tai

Mount Tai () is a mountain of historical and cultural significance located north of the city of Tai'an. It is the highest point in Shandong province, China. The tallest peak is the '' Jade Emperor Peak'' (), which is commonly reported as being ...

; for others it is as insignificant as a goose down. The difference is what they use it for." (人固有一死,或重于泰山,或輕于鴻毛,用之所趨異也。) This quote has become one of the most well known in all of Chinese literature. In modern times, Chairman Mao paraphrased this quote in a speech in which he paid tribute to a fallen PLA

PLA may refer to:

Organizations Politics and military

* People's Liberation Army, the armed forces of China and of the ruling Chinese Communist Party

* People's Liberation Army (disambiguation)

** Irish National Liberation Army, formerly called ...

soldier.

Sima Qian wrote eight rhapsodies ('' fu''), which are listed in the bibliographic treatise of the ''Book of Han''. All but one, the "Rhapsody in Lament for Gentlemen who do not Meet their Time" (士不遇賦) have been lost, and even the surviving example is probably not complete.

Astronomer/astrologer

Sima and his father both served as the ''taishi'' (太史) of theFormer Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

, a position which includes aspects of being a historian, a court scribe, calendarist, and court astronomer/astrologer. At that time, the astrologer had an important role, responsible for interpreting and predicting the course of government according to the influence of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as other astronomical and geological phenomena such as solar eclipses and earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s, which depended on revising and upholding an accurate calendar.

Before compiling ''Shiji'', Sima Qian was involved in the creation of the 104 BC '' Taichu'' Calendar 太初暦 (太初 became the new era name

A regnal year is a year of the reign of a sovereign, from the Latin ''regnum'' meaning kingdom, rule. Regnal years considered the date as an ordinal, not a cardinal number. For example, a monarch could have a first year of rule, a second year of ...

for Emperor Wu and means "supreme beginning"), a modification of the Qin Qin may refer to:

Dynasties and states

* Qin (state) (秦), a major state during the Zhou Dynasty of ancient China

* Qin dynasty (秦), founded by the Qin state in 221 BC and ended in 206 BC

* Daqin (大秦), ancient Chinese name for the Roman Emp ...

calendar. This is the first Chinese calendar whose full method of calculation (暦法) has been preserved.

The minor planet "12620 Simaqian" is named in his honour.

Family

Sima Qian is the son of court astrologer (太史令)Sima Tan

Sima Tan (; 165–110 BCE) was a Chinese astrologer and historian during the Western Han dynasty. His work ''Records of the Grand Historian'' was completed by his son Sima Qian, who is considered the founder of Chinese historiography.

Ed ...

, who is a descendant of Qin Qin may refer to:

Dynasties and states

* Qin (state) (秦), a major state during the Zhou Dynasty of ancient China

* Qin dynasty (秦), founded by the Qin state in 221 BC and ended in 206 BC

* Daqin (大秦), ancient Chinese name for the Roman Emp ...

general Sima Cuo (司馬錯), the commander of Qin army in the state's conquest of Ba and Shu.

Before his castration, Sima Qian was recorded to have two sons and a daughter. While little is recorded of his sons, his daughter later married Yang Chang (楊敞), and had sons Yang Zhong (楊忠) and Yang Yun (楊惲). It was Yang Yun who hid his grandfather's great work, and decided to release it during the reign of Emperor Xuan.

Unsubstantiated descendants

According to local legend, Sima Qian had two sons, the older named Sima Lin (司馬臨) and younger named Sima Guan (司馬觀), who fled the capital to Xu Village (徐村) in what is now Shanxi province during the Li Ling affair, for fear of falling victim to familial extermination. They changed their surnames to Tong (同 = 丨+ 司) and Feng (馮 = 仌 + 馬), respectively, to hide their origins while continuing to secretly offer sacrifices to the Sima ancestors. To this day, people living in the village with surnames Feng and Tong are forbidden from intermarrying on the grounds that the relationship would be incestuous. According to the ''Book of Han'',Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the thron ...

sent an expedition to search for and ennoble a male-line descent of Sima Qian as 史通子 ("Viscount of Historical Mastery"), although it was not recorded who received this title of nobility. A Qing dynasty stele 重修太史廟記 (''Records of the Renovation of the Temple of the Grand Historian'') erected in the nearby county seat Han City (韓城) claims that the title was given to the grandson of Sima Lin.

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * *Further reading

*Markley, J. ''Peace and Peril. Sima Qian's portrayal of Han - Xiongnu relations'' (''Silk Road Studies'' XIII), Turnhout, 2016, *Allen, J.R "An Introductory Study of Narrative Structure in the ''Shi ji''" pages 31–61 from ''Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews'', Volume 3, Issue 1, 1981. *Allen, J.R. "Records of the Historian" pages 259–271 from ''Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective: A Guide for Teaching'', Armonk: Sharpe, 1994. *Beasley, W. G & Pulleyblank, E. G ''Historians of China and Japan'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961. *Dubs, H.H. "History and Historians under the Han" pages 213-218 from ''Journal of Asian Studies'', Volume 20, Issue # 2, 1961. *Durrant S.W "Self as the Intersection of Tradition: The Autobiographical Writings of Ssu-Ch'ien" pages 33–40 from ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'', Volume 106, Issue # 1, 1986. *Cardner, C. S ''Traditional Historiography'', Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970. *Hardy, G.R "Can an Ancient Chinese historian Contribute to Modern Western Theory?" pages 20–38 from ''History and Theory'', Volume 33, Issue # 1, 1994. *Kroll, J.L "Ssu-ma Ch'ien Literary Theory and Literary Practice" pages 313-325 from ''Altorientalische Forshungen'', Volume 4, 1976. *Li, W.Y "The Idea of Authority in the ''Shi chi''" pages 345-405 from ''Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies'', Volume 54, Issue # 2, 1994. *Moloughney, B. "From Biographical History to Historical Biography: A Transformation in Chinese Historical Writings" pages 1–30 from ''East Asian History'', Volume 4, Issue 1, 1992.External links

* * *Significance of ''Shiji'' on literature

Sima Qian: China's 'grand historian'

article by Carrie Gracie in BBC News Magazine, 7 October 2012 {{DEFAULTSORT:Sima, Qian 86 BC deaths 2nd-century BC births 2nd-century BC Chinese historians 1st-century BC Chinese historians 1st-century BC Chinese poets Ancient astrologers Chinese astrologers Chinese prisoners sentenced to death Han dynasty eunuchs Han dynasty historians Han dynasty poets Han dynasty politicians from Shaanxi Historians from Shaanxi Poets from Shaanxi Prisoners sentenced to death by China Legendary Chinese people