Silwood Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Silwood Park is the rural campus of

Silwood Park is the rural campus of

Prior to

Prior to  In 1947, Silwood Park was purchased by Imperial College for

In 1947, Silwood Park was purchased by Imperial College for

Silwood Park Campus

{{authority control Buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead Country houses in Berkshire Educational institutions established in 1947 Education in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead Imperial College London Natural Environment Research Council Parks and open spaces in Berkshire Research institutes in Berkshire 1947 establishments in England Sunninghill and Ascot

Silwood Park is the rural campus of

Silwood Park is the rural campus of Imperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, England. It is situated near the village of Sunninghill, near Ascot in Berkshire. Since 1986, there have been major developments on the site with four new college buildings. Adjacent to these buildings is the Technology Transfer Centre: a science park

A science park (also called a "university research park", "technology park”, "technopark", “technopole", or a "science and technology park" (STP)) is defined as being a property-based development that accommodates and fosters the growt ...

with units leased to commercial companies for research.

There are a number of the divisions of Faculty of Natural Sciences that have a presence on the campus. Additionally, Silwood Park is home to the NERC Centre for Population Biology (CPB), the International Pesticide Application Research Consortium (IPARC).

History

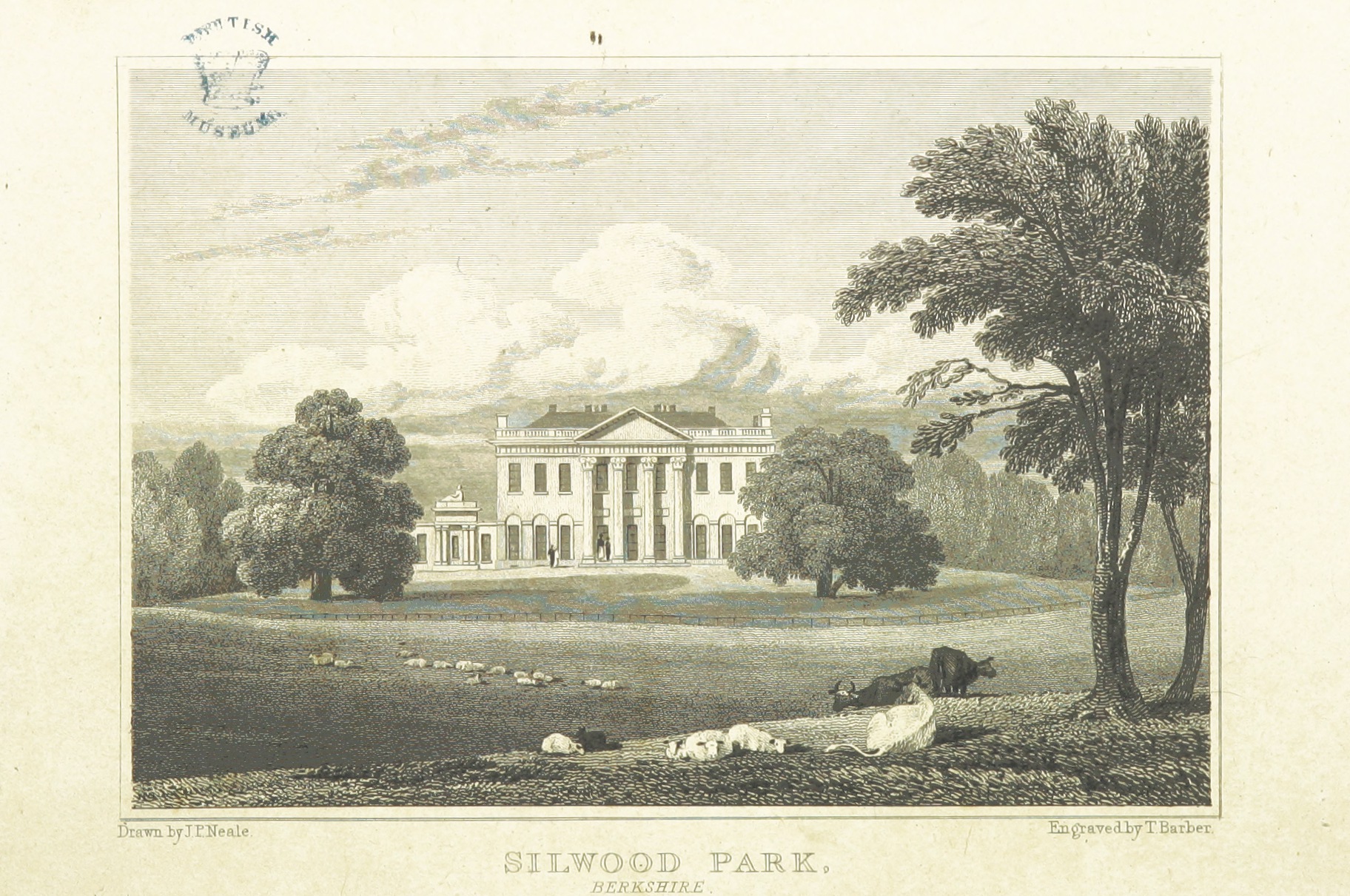

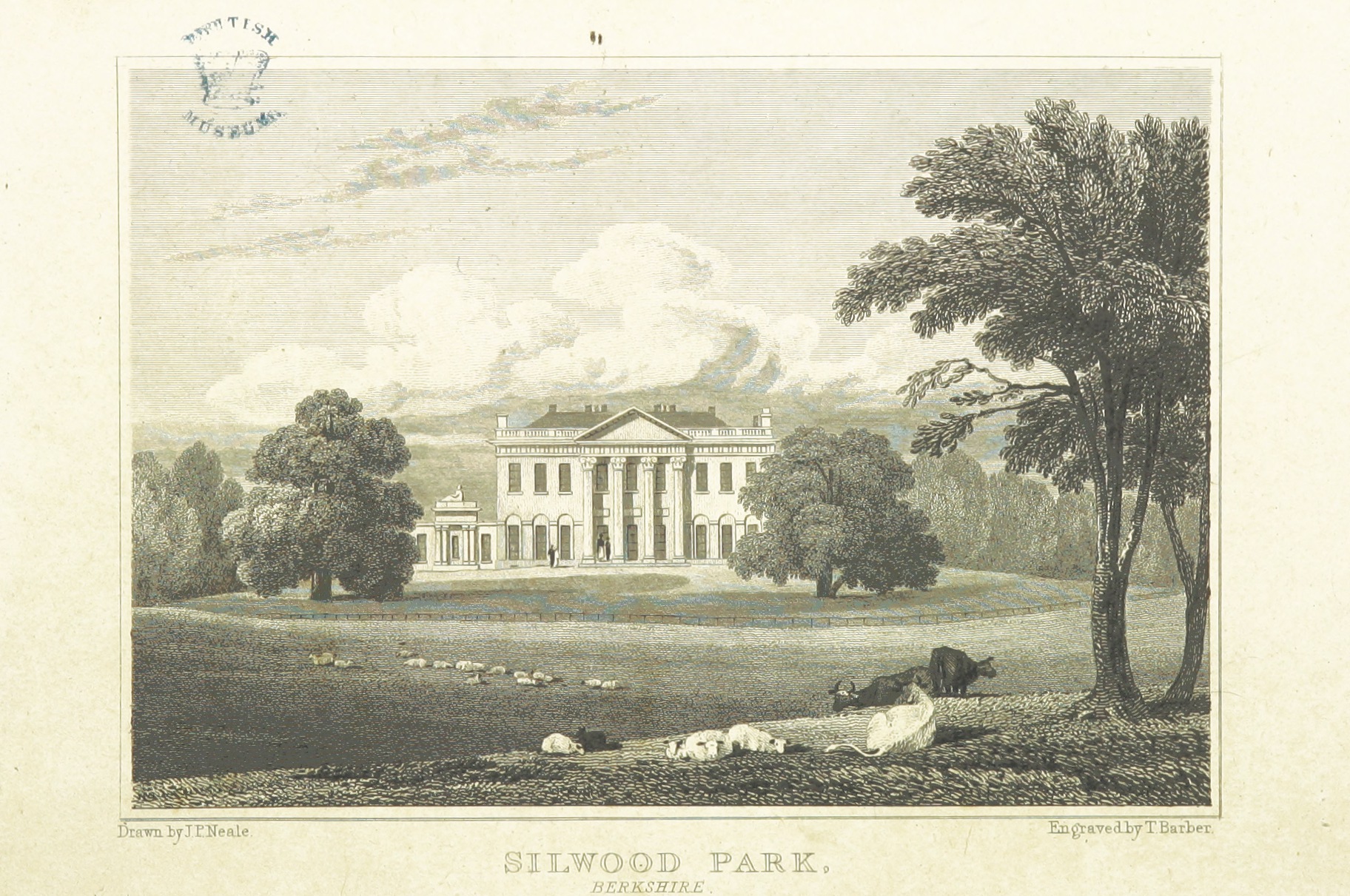

Prior to

Prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Silwood Park was a private residence

A residence is a place (normally a building) used as a home or dwelling, where people reside.

Residence may more specifically refer to:

* Domicile (law), a legal term for residence

* Habitual residence, a civil law term dealing with the status ...

—the manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals ...

of Sunninghill—then during the war, it became a convalescent home

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

for airmen. The original manor at which Prince Arthur stayed in 1499 was known as Eastmore and was situated on the hill near Silwood Farm. In about 1788, Sir James Sibbald built a neo-classical Georgian mansion by architect Robert Mitchell (1770-1809) on part of the present house and demolished the old "Eastmore"; he called it ''Selwood'' or ''Silwood Park''. The name stems from the Old English for Sallow (''Salix caprea

''Salix caprea'', known as goat willow, pussy willow or great sallow, is a common species of willow native to Europe and western and central Asia.Meikle, R. D. (1984). ''Willows and Poplars of Great Britain and Ireland''. BSBI Handbook 4. .

Des ...

'' Agg.) which presumably grew then along the banks of the streams that flow through the Park. The grounds were landscaped by Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton (21 April 1752 – 24 March 1818) was the last great English landscape designer of the eighteenth century, often regarded as the successor to Capability Brown; he also sowed the seeds of the more intricate and eclectic styles of ...

, most celebrated landscape designer of his generation.

In 1854 Silwood was bought by Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Although some were driven b ...

owner John Hargreaves Jr from the widow of Mr Forbes and ''Silwood Lodge'' added thereafter. Mary Hargreaves (née Hick) received socialite

A socialite is a person from a wealthy and (possibly) aristocratic background, who is prominent in high society. A socialite generally spends a significant amount of time attending various fashionable social gatherings, instead of having tradit ...

Rose O'Neale Greenhow as a guest in April 1864 and was an associate of novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire ...

Mrs Oliphant

Margaret Oliphant Wilson Oliphant (born Margaret Oliphant Wilson; 4 April 1828 – 20 June 1897) was a Scottish novelist and historical writer, who usually wrote as Mrs. Oliphant. Her fictional works cover "domestic realism, the historical nove ...

. John Hargreaves died in 1874 and his trustees

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to t ...

, one of whom was John Hick, sold the estate to engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

Charles Patrick Stewart in 1875. ''Silwood Park'' and ''Silwood Lodge'' were demolished in 1876 and the present mansion commissioned by Stewart to the design of Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known ...

, completed in 1878. Stewart was keen on horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic pr ...

and partying, and built his new house around a grand ballroom

A ballroom or ballhall is a large room inside a building, the primary purpose of which is holding large formal parties called balls. Traditionally, most balls were held in private residences; many mansions and palaces, especially historic ...

where, on race days and holidays he would entertain the sons of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

amongst other racing enthusiasts. Architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

described the new manor house as ''"Red brick and huge. Free Tudor with a freer tower"''. Waterhouse's use of Silwood-style bricks for new university buildings at Manchester and London gave rise to the phrase '' red-brick universities''.

In 1947, Silwood Park was purchased by Imperial College for

In 1947, Silwood Park was purchased by Imperial College for entomological

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arach ...

research and field studies. Initially, pioneering developments in insect pest management took place, but more recently the emphasis has been on ecology and evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary biology. Staff and research students of the Zoology Department were the first college personnel at Silwood when the Field Station moved from Slough

Slough () is a town and unparished area in the unitary authority of the same name in Berkshire, England, bordering west London. It lies in the Thames Valley, west of central London and north-east of Reading, at the intersection of the ...

, but the department of Civil Engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

has used it since 1947 for courses in surveying. Botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

started work there about thirty years ago and the nuclear reactor was opened in 1965. Over a thousand postgraduate students have been trained at Silwood since its establishment, about half of them taking PhDs. They have come from more than sixty countries, and Silwood-trained graduates have gone to almost every corner of the globe. There are over 200 graduate staff and students working there at any one time. Undergraduates from South Kensington attend for field courses and some final-year projects. In 1981, the departments of Zoology and Botany were merged to form the Department of Biology.

A low power nuclear research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or marit ...

(100 kW thermal), named CONSORT II, was licensed at the site on 20 December 1962, completed February 1963, and achieved first criticality in 1965. After a decline in research conducted there, the reactor was shutdown in 2012 and defueled by 2014. The reactor was decommissioned in 2021, followed by the demolition of the reactor building.

In 1984, the CAB International

CABI (legally CAB International, formerly Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux) is a nonprofit intergovernmental development and information organisation focusing primarily on agricultural and environmental issues in the developing world, and the c ...

Institute of Biological Control (IIBC) moved its headquarters to Silwood Park. From 1989-2008, the Institute occupied its own new building at Silwood Park, which also housed the Michael Way Library, specialising in ecology, entomology and crop protection. From January 1998, IIBC and its sister Institutes of Entomology, Mycology and Parasitology were integrated on two sites as CABI Bioscience. The Silwood site was the centre for the LUBILOSA

LUBILOSA was the name of a research programme that aimed at developing a biological alternative to the chemical control of locusts. This name is an acronym of the French title of the programme: Lutte Biologique contre les Locustes et les Sauteri ...

Programme, where an inter-disciplinary team could be set up, combining IIBCs biological control

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as insects, mites, weeds, and plant diseases, using other organisms. It relies on predation, parasitism, herbivory, or other natural mechanisms, but typically also i ...

skills with (bio)pesticide application

Pesticide application refers to the practical way in which pesticides (including herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, or nematode control agents) are delivered to their ''biological targets'' (''e.g.'' pest organism, crop or other plant). Publ ...

( IPARC) and host-pathogen ecology (CPB). CABI continued to focus on biological pest, disease and weed management in Silwood Park until consolidation at Egham

Egham ( ) is a university town in the Borough of Runnymede in Surrey, England, approximately west of central London. First settled in the Bronze Age, the town was under the control of Chertsey Abbey for much of the Middle Ages. In 1215, Magna ...

(to become the UK Centre) in 2008. The celebrated Entomology Masters in Science (Msc) course was suspended in 2012, causing faculty to move their work to Harper Adams University

Harper Adams University, founded in 1901 as Harper Adams College, is a public university located close to the village of Edgmond, near Newport, in Shropshire, England. Established in 1901, the college is a specialist provider of higher educa ...

.

See also

*LUBILOSA

LUBILOSA was the name of a research programme that aimed at developing a biological alternative to the chemical control of locusts. This name is an acronym of the French title of the programme: Lutte Biologique contre les Locustes et les Sauteri ...

* Richard Southwood

Sir Thomas Richard Edmund Southwood GOM DL FRS (20 June 1931 – 26 October 2005) was a British biologist, Professor of Zoology and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford. A specialist on entomology, he developed the field of insect eco ...

References

External links

Silwood Park Campus

{{authority control Buildings and structures in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead Country houses in Berkshire Educational institutions established in 1947 Education in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead Imperial College London Natural Environment Research Council Parks and open spaces in Berkshire Research institutes in Berkshire 1947 establishments in England Sunninghill and Ascot