Siege of Oxford (1142) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Oxford took place during

The siege of Oxford took place during

Although the size of the army Matilda took with her to Oxford is unknown, it contained only a few barons with whom she could keep a "small court", and for whom she could provide from the local lands of the royal demesne. Oxford's relative proximity to the capital, suggests Bradbury, also made it a "brave move" on her part; it probably also indicates that she did not wish to move too far and that she intended to return to, and reclaim, London in due course.

Matilda recognised that her lack of resources meant that she could not bring the war to a decisive close at this point, and so she sent her half-brother,

Although the size of the army Matilda took with her to Oxford is unknown, it contained only a few barons with whom she could keep a "small court", and for whom she could provide from the local lands of the royal demesne. Oxford's relative proximity to the capital, suggests Bradbury, also made it a "brave move" on her part; it probably also indicates that she did not wish to move too far and that she intended to return to, and reclaim, London in due course.

Matilda recognised that her lack of resources meant that she could not bring the war to a decisive close at this point, and so she sent her half-brother,

Following Stephen's recovery, says the author of the anti-Angevin ''Gesta'', the King acted like a man "awakened as out of sleep". He approached Oxford rapidly from the south-west; although the size of his army is unknown, he had already won a series of small but significant victories, punching a gap into the Angevin-controlled south-west. This won him the port town of Wareham—cutting the Angevins' line of communication with their continental heartlands—and

Following Stephen's recovery, says the author of the anti-Angevin ''Gesta'', the King acted like a man "awakened as out of sleep". He approached Oxford rapidly from the south-west; although the size of his army is unknown, he had already won a series of small but significant victories, punching a gap into the Angevin-controlled south-west. This won him the port town of Wareham—cutting the Angevins' line of communication with their continental heartlands—and

For the second time in the war, Stephen almost succeeded in capturing Matilda, but for the second time also, failed in the attempt. After three months' siege, supplies and provisions within Oxford Castle had become dangerously low, and, suggests Castor, "trapped inside a burned and blackened city, Matilda and her small garrison were cold, starving and almost bereft of hope." Matilda—thanks to the "ingenuity" of her garrison, says

For the second time in the war, Stephen almost succeeded in capturing Matilda, but for the second time also, failed in the attempt. After three months' siege, supplies and provisions within Oxford Castle had become dangerously low, and, suggests Castor, "trapped inside a burned and blackened city, Matilda and her small garrison were cold, starving and almost bereft of hope." Matilda—thanks to the "ingenuity" of her garrison, says

Stephen's exact movements after the siege are hard to establish; Oxford Castle dominated the surrounding countryside, and he probably took advantage of his new-found lordship to spend considerable time and resources subduing the countryside around Oxford. After all, says Emilie Amt, in the county generally, "far more important than the Angevins' one-time foothold here were the Angevin loyalties of many Oxfordshire barons". Stephen knew Matilda had fled to Wallingford after her escape, but made no effort to stop her. Stephen had attempted to besiege the castle in 1139, Fitz Count had "strengthened the already impregnable castle" over the years, as well as having sufficient provisions to hold out for several years, which Stephen had discovered to his cost: his siege had broken up within weeks. Stephen clearly did not wish to attempt a second assault. The King is known to have attended a

Stephen's exact movements after the siege are hard to establish; Oxford Castle dominated the surrounding countryside, and he probably took advantage of his new-found lordship to spend considerable time and resources subduing the countryside around Oxford. After all, says Emilie Amt, in the county generally, "far more important than the Angevins' one-time foothold here were the Angevin loyalties of many Oxfordshire barons". Stephen knew Matilda had fled to Wallingford after her escape, but made no effort to stop her. Stephen had attempted to besiege the castle in 1139, Fitz Count had "strengthened the already impregnable castle" over the years, as well as having sufficient provisions to hold out for several years, which Stephen had discovered to his cost: his siege had broken up within weeks. Stephen clearly did not wish to attempt a second assault. The King is known to have attended a

The siege of Oxford took place during

The siege of Oxford took place during The Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

—a period of civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

following the death of Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

without an heir—in 1142. Fought between his nephew, Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unti ...

, and his daughter, the Empress Matilda (or Maud), who had recently been expelled from her base in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

and chosen the City of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the U ...

as her new headquarters. Oxford by now was effectively a regional capital and important in its own right. It was a well-defended city with both rivers and walls protecting it, and was also strategically important as it was at a crossroads

Crossroads, crossroad, cross road or similar may refer to:

* Crossroads (junction), where four roads meet

Film and television Films

* ''Crossroads'' (1928 film), a 1928 Japanese film by Teinosuke Kinugasa

* ''Cross Roads'' (film), a 1930 Brit ...

between the north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

, south-east

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each s ...

and west of England

West of England is a combined authority area in South West England. It is made up of the Bristol, South Gloucestershire, and Bath and North East Somerset unitary authorities. The combined authority is led by the Mayor of the West of England Dan ...

, and also not far from London.

By now the civil war was at its height, yet neither party was able to get an edge on the other: both had suffered swings of fate in the last few years which had alternately put them ahead, and then behind, their rival. Stephen, for instance, had been captured by Matilda's army in 1141, but later in the year, Matilda's half-brother and chief military commander, Robert, Earl of Gloucester

Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester (c. 1090 – 31 October 1147David Crouch, 'Robert, first earl of Gloucester (b. c. 1090, d. 1147)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200Retrieved ...

was captured by Stephen's army. Likewise, Matilda had been recognised as "Lady of the English" but had not long afterwards been run out of London.

Stephen believed that all it would take to win the war decisively would be to capture Matilda herself; her escape to Oxford seemed to present him with such an opportunity. Having raised a large army in the north, he returned south and attacked Wareham in Dorset; this port town was important to Matilda's Angevin party as it provided one of the few direct links to the continent that they controlled. He attacked and captured more towns as he returned to the Thames Valley, and soon the only significant base Matilda had outside of the south-west—apart from Oxford itself—was at Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

, held by her close supporter Brian Fitz Count.

Stephen's army approached Oxford in late September 1142, and according to contemporary accounts, swam his army across the rivers and waterways that blocked the approach to the city. Matilda's small force was taken by surprise. Those that were not killed or captured retreated into the castle; Stephen now controlled the city, which protected him from counterattack. The king knew he was unlikely to be able to take the castle by force—although that did not stop him from using the latest siege technology. He also knew that it would be a long, hard wait before Matilda was starved out. But after nearly three months of siege, conditions for the garrison were dire, and they formed a plan to help the Empress escape from under Stephen's nose. One early December evening Matilda crept out of a postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location which allowed the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern ...

door in the wall—or, more romantically, possibly shinned down on a rope out of St George's Tower—dressed in white as camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

against the snow and passed without capture through Stephen's lines. She escaped to Wallingford and then to Abingdon, where she was safe; Oxford Castle surrendered to Stephen the following day, and the war continued punctuated by a series of sieges for the next 11 years.

Background

Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the N ...

died without a male heir in 1135, leading to a succession crisis A succession crisis is a crisis that arises when an order of succession fails, for example when a king dies without an indisputable heir. It may result in a war of succession.

Examples include (see List of wars of succession):

*Multiple periods ...

. His only legitimate son and heir, William Adelin, had died in the sinking of the '' White Ship'' in 1120. Henry wished his daughter the Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, to succeed him, but female succession rights were ill-defined at this time—indeed, there had not been an uncontested succession to the Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

patrimony during the previous sixty years. On Henry's death in 1135, his nephew Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unti ...

claimed and seized the English throne; fighting broke out within a few years, eventually becoming a fully-fledged rebellion against Stephen, as Matilda also claimed the English throne. By 1138 the dispute had escalated into a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

known as the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

. The Empress Matilda had recently been expelled from Westminster Palace

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

by rebellious Londoners, who had "swarmed out like angry wasps" from London, while Stephen's queen—also named Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

—approached Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

from Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. The Empress Matilda—"in great state", reported James Dixon Mackenzie—evacuated to Oxford in 1141, making it her headquarters and setting up her Mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAE ...

. Prior to her eviction from Westminster, she had made some political gains, having captured King Stephen and been recognised as "the Lady of the English". Although Matilda never matched the King in wealth, both sides' armies probably ranged in size from 5,000 to 7,000 men.

Oxford

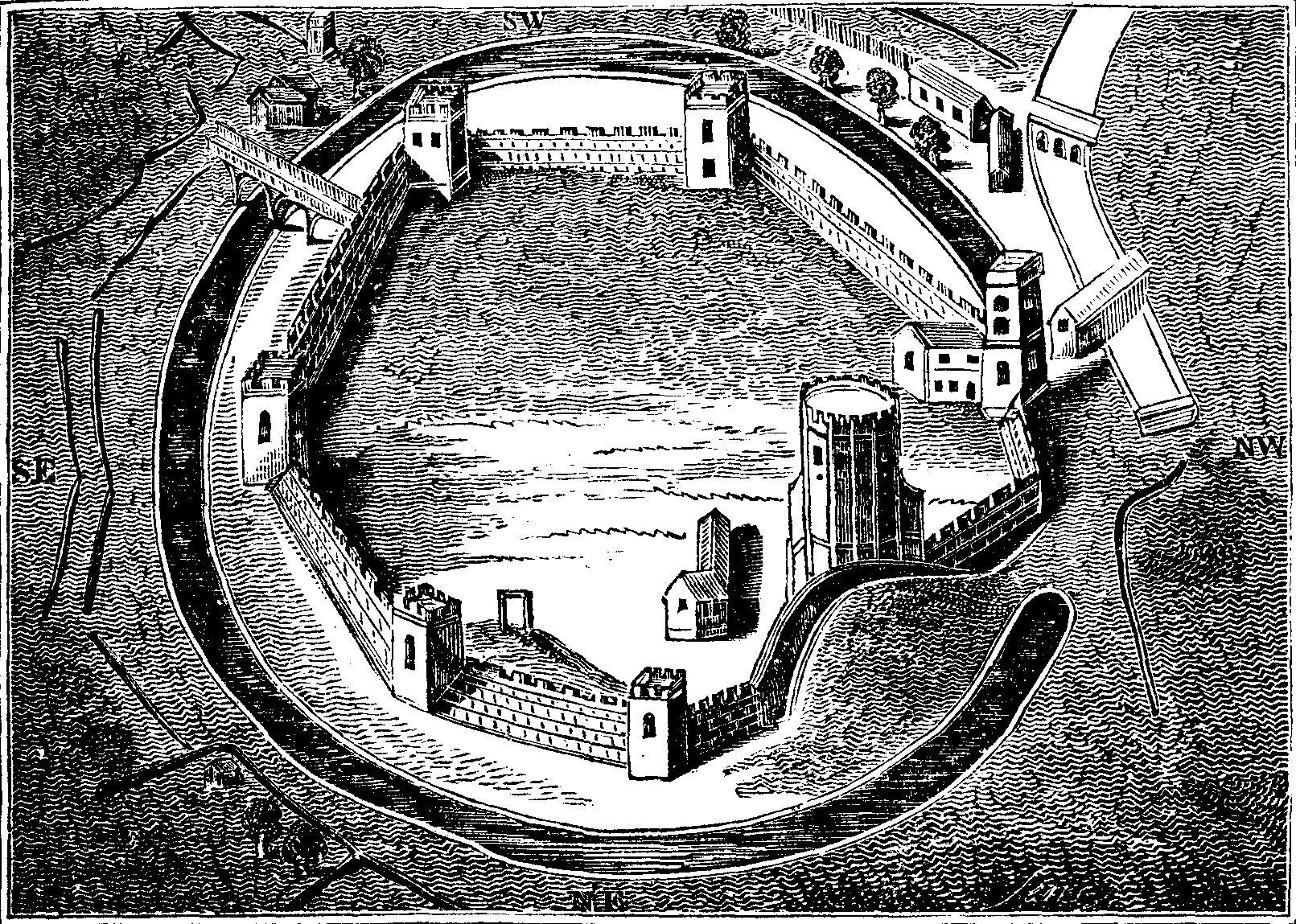

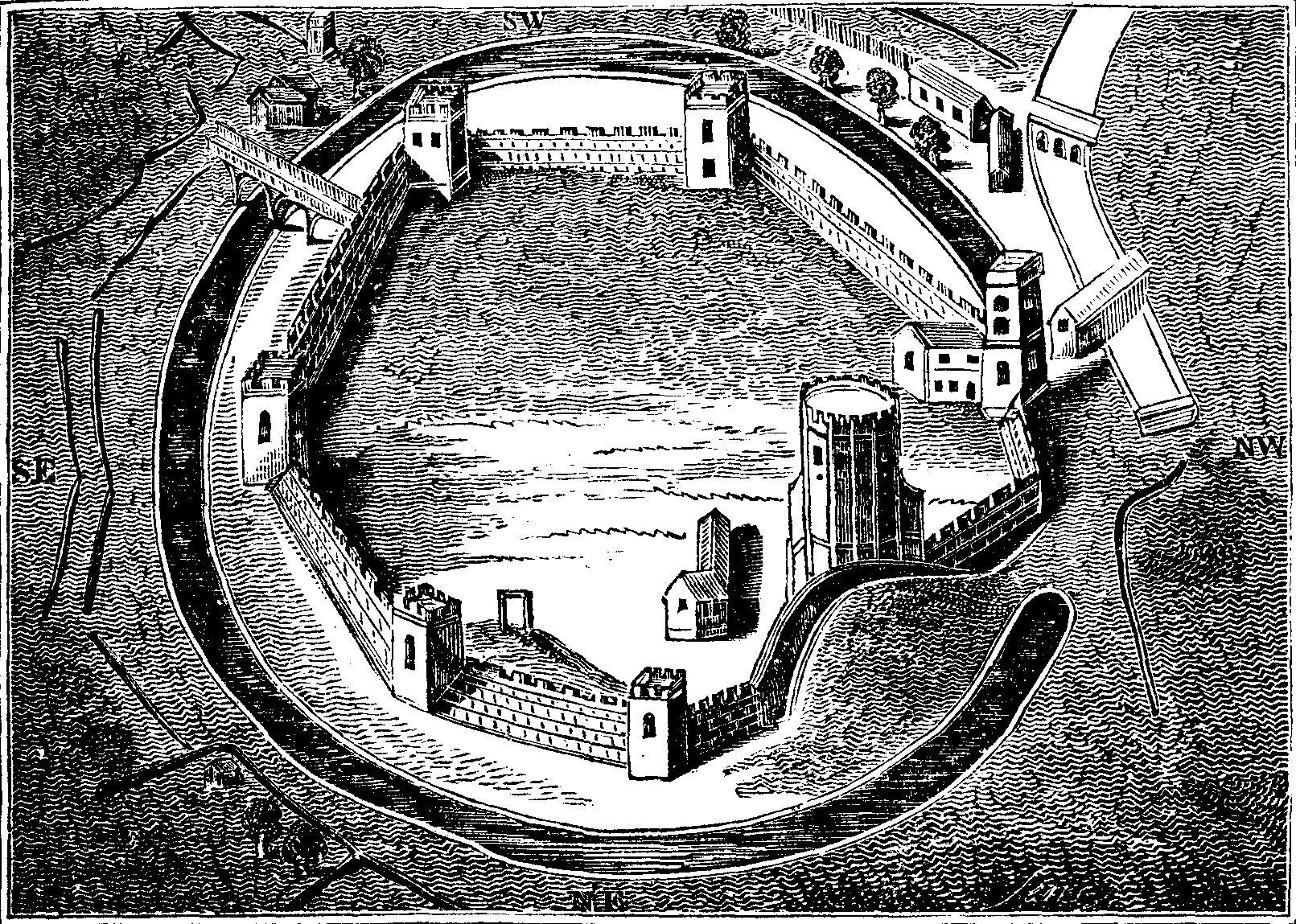

Oxford itself had become increasingly important by this period, and, in the words of historian Edmund King, it was "in the course of becoming a regional capital". It also had a royalcastle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

. Its value for whoever held it was not merely symbolic; it was also of great practical value. It was particularly secure, surrounded as it was, says the author of the ''Gesta Stephani

__NOTOC__

''Deeds of King Stephen'' or ''Acts of Stephen'' or ''Gesta Regis Stephani'' is a mid-12th-century English history by an anonymous author about King Stephen of England and his struggles with his cousin, Empress Matilda, also known as the ...

'', by "very deep water that washes it all around" and ditches. The Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Ber ...

-Oxfordshire interface area was a contentious one throughout the war, and Oxford particularly was of great strategic value. It was situated at the nexus of the main routes from London to the south-west and from Southampton to the north. Whoever controlled the Oxford area effectively controlled access to London and the north, and for Stephen it provided a bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

for attacking Matilda's south-western heartlands. Although the size of the army Matilda took with her to Oxford is unknown, it contained only a few barons with whom she could keep a "small court", and for whom she could provide from the local lands of the royal demesne. Oxford's relative proximity to the capital, suggests Bradbury, also made it a "brave move" on her part; it probably also indicates that she did not wish to move too far and that she intended to return to, and reclaim, London in due course.

Matilda recognised that her lack of resources meant that she could not bring the war to a decisive close at this point, and so she sent her half-brother,

Although the size of the army Matilda took with her to Oxford is unknown, it contained only a few barons with whom she could keep a "small court", and for whom she could provide from the local lands of the royal demesne. Oxford's relative proximity to the capital, suggests Bradbury, also made it a "brave move" on her part; it probably also indicates that she did not wish to move too far and that she intended to return to, and reclaim, London in due course.

Matilda recognised that her lack of resources meant that she could not bring the war to a decisive close at this point, and so she sent her half-brother, Robert, Earl of Gloucester

Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester (c. 1090 – 31 October 1147David Crouch, 'Robert, first earl of Gloucester (b. c. 1090, d. 1147)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200Retrieved ...

, to her husband, the Count of Anjou, to try to bring him and his large, experienced army in on her side. Matilda and the earl probably assumed that she would be safe in Oxford until he returned. This was a crucial period for Matilda, says King, and Gloucester's absence weakened her force further: he left for Normandy on 24 June to negotiate with Anjou, despite, says Crouch, Matilda's situation being "desperate". However, she considered Oxford to be her "own town", commented the 17th-century antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

Samuel Daniel

Samuel Daniel (1562–1619) was an English poet, playwright and historian in the late-Elizabethan and early- Jacobean eras. He was an innovator in a wide range of literary genres. His best-known works are the sonnet cycle ''Delia'', the e ...

. Stephen had recently been so ill that it was feared, temporarily, that he was dying; this created a degree of popular sympathy for him, which had already welled up following his release from Matilda's captivity the previous November. A. L. Poole described the train of events thus:

Matilda and Gloucester, on the other hand, did not know that he was on the road to recovery; if they had, suggests R. H. C. Davis, they might not have delayed or even cancelled his journey. However, they did not, and Matilda's army was effectively left leaderless. Matilda may have been expecting supporters to make their way to Oxford—"to 'make fine' with her" (i.e. to contract themselves to her cause), suggests Edmund King—"but they were under no compulsion to do so". It is likely, says Professor H. A. Cronne, that by now "the tide had turned and already men were quietly leaving her court". John Appleby, too, has suggested that much of her support had by now decided that, in his words, they had "bet on the wrong horse", particularly as she had failed to put up a stand at Westminster or immediately return in force. Stephen, on the other hand, had recuperated in the north of England; he had a solid base of support there and was able to raise a large army—possibly over 1,000 knights—before returning south.

The siege

Following Stephen's recovery, says the author of the anti-Angevin ''Gesta'', the King acted like a man "awakened as out of sleep". He approached Oxford rapidly from the south-west; although the size of his army is unknown, he had already won a series of small but significant victories, punching a gap into the Angevin-controlled south-west. This won him the port town of Wareham—cutting the Angevins' line of communication with their continental heartlands—and

Following Stephen's recovery, says the author of the anti-Angevin ''Gesta'', the King acted like a man "awakened as out of sleep". He approached Oxford rapidly from the south-west; although the size of his army is unknown, he had already won a series of small but significant victories, punching a gap into the Angevin-controlled south-west. This won him the port town of Wareham—cutting the Angevins' line of communication with their continental heartlands—and Cirencester

Cirencester (, ; see below for more variations) is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of ...

, as well as the castles of Rampton and Bampton. The capture of those two castles, in turn, cut Matilda's lines of communication between Oxford and the south-west and opened the Oxford road to Stephen on his return. He probably travelled via Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish includes the hamlets of Nether Coombe and Lower Clatcombe. ...

, Castle Cary

Castle Cary () is a market town and civil parish in south Somerset, England, north west of Wincanton and south of Shepton Mallet, at the foot of Lodge Hill and on the River Cary, a tributary of the Parrett.

History

The word Cary derives fr ...

, Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

and Malmesbury

Malmesbury () is a town and civil parish in north Wiltshire, England, which lies approximately west of Swindon, northeast of Bristol, and north of Chippenham. The older part of the town is on a hilltop which is almost surrounded by the upp ...

, all of which were held by his supporters (and conversely, suggests Davis, avoided Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, Marlborough, Devizes and Trowbridge

Trowbridge ( ) is the county town of Wiltshire, England, on the River Biss in the west of the county. It is near the border with Somerset and lies southeast of Bath, 31 miles (49 km) southwest of Swindon and 20 miles (32 km) southeas ...

, which were held for the Empress).

Stephen arrived at the river bank looking over to Oxford on the evening of 26 September 1142: the city was unprepared for his arrival. David Crouch comments that the King "had chosen his time well": the city's and castle's previous castellan

A castellan is the title used in Medieval Europe for an appointed official, a governor of a castle and its surrounding territory referred to as the castellany. The title of ''governor'' is retained in the English prison system, as a remnant ...

, Robert d'Oilly had died a fortnight earlier and his successor had yet to be appointed. Thus the only military presence in Oxford was the Empress' armed householdmen, a relatively small force of soldiers. They "bravely or foolishly turned out to dispute his crossing of the river", and, thinking themselves secure, taunted Stephen's army from the safety of the city's ramparts, raining them with arrow fire across the river. While the Queen's army offered battle outside the city, Stephen was intent on besieging the castle without a battle, but this meant taking the city first. Stephen's men had to navigate a series of watercourse

A stream is a continuous body of surface water flowing within the bed and banks of a channel. Depending on its location or certain characteristics, a stream may be referred to by a variety of local or regional names. Long large streams a ...

s, what the Gesta describes as an "old, extremely deep, ford". They successfully crossed—at least one chronicler believed them to have swum at one point—and entered Oxford the same day by a postern gate. The Empress' garrison, both surprised and outnumbered, and probably panicking, beat a hasty retreat up to the castle. Those that were caught were either killed or kept for ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French ''rançon'' from Latin ''re ...

; the city itself was looted and burned

Burned or burnt may refer to:

* Anything which has undergone combustion

* Burned (image), quality of an image transformed with loss of detail in all portions lighter than some limit, and/or those darker than some limit

* ''Burnt'' (film), a 2015 ...

. Matilda was thus stranded in Oxford Castle with an even smaller force than that she had entered the city with;

Stephen's primary objective in besieging Oxford was the capture of the Empress rather than the city or castle itself, reported the chronicler John of Gloucester

John of Gloucester (or John of Pontefract) (c. 1468 - c. 1499 (based on historical hypothesis)) was an illegitimate son of King Richard III of England. John is so called because his father was Duke of Gloucester at the time of his birth. His fathe ...

. Another, William of Malmsbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a ...

, suggests that Stephen believed that capturing Matilda would end the civil war in one fell stroke, and the ''Gesta'' declares that "the hope of no advantage, the fear of no loss" would distract the King. This was public knowledge, and for the Earl of Gloucester in Normandy, gave his mission an added urgency. Oxford Castle was well provisioned, and a long siege was inevitable; but Stephen was "content to endure a long siege to starve out his prey, even though the winter conditions would be horrible for his own men" say Gravett and Hook. Stephen, though, had a good grasp of siegecraft

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteri ...

. He prevented the besieged from foraging

Foraging is searching for wild food resources. It affects an animal's fitness because it plays an important role in an animal's ability to survive and reproduce. Foraging theory is a branch of behavioral ecology that studies the foraging behavi ...

by pillaging the surrounding area himself, and showed a certain ingenuity in his varied use of technology, including belfries, battering ram

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, heavy log carried b ...

s and mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel o ...

s. This allowed him, points out Keith Stringer, to attack the city walls both up-close and from afar simultaneously. Stephen did not hesitate. He made his headquarters in what was later known as Beaumont Palace, just outside the city wall's north gate. Although not particularly well fortified, it was easily defensible with a strong wall and gate. He brought up siege artillery, which he placed on two artificially constructed siege mounts called Jew's Mount and Mount Pelham, situated between Beaumont Palace and the north wall. These kept the castle under suppressing fire

In military science, suppressive fire is "fire that degrades the performance of an enemy force below the level needed to fulfill its mission". When used to protect exposed friendly troops advancing on the battlefield, it is commonly called cove ...

, and it is possible that these mounds, being so close together, were more like a motte-and-bailey structure on the edge of the city, rather than two discrete siege works. Apart from effecting damage to the castle, they had the added benefit of worsening the morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

of the inhabitants. Meanwhile, the King's guards kept watch for the Empress 24 hours a day. Because Stephen had been able to take the city without damaging its walls, these now worked in his favour and meant he could press his attack against Matilda while protecting his flanks. The added consequence for Matilda was that it made rescue even more difficult, as whoever undertook the mission would have to dislodge Stephen from the well-fortified walls before even reaching the siege. There was a locus of sympathisers about away, at Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

says Crouch, but they were "impotent" to reach her or help her escape. Bradbury suggests that they probably lacked numerical superiority over the King's army and that this deterred them. Matilda's small force, meanwhile, remained "pinned down" by the royal blockade, and eventually began to run low on provisions.

In December the Earl of Gloucester returned to England, bringing with him a force of between 300 and 400 men and knights in 52 ships. In a sop to Matilda's demands, the Count had allowed her nine-year-old son Henry to accompany the earl. His mission to bring the Count and his army to England had been a failure. Anjou had refused to leave Normandy or make any attempt to rescue his wife; perhaps, says Cronne, "it was just as well he did, for the English barons would certainly have regarded him as an unwelcome intruder". On Gloucester's return he placed Wareham under siege, probably hoping that Stephen would raise his siege at Oxford and come to the relief of Wareham; but if it was a bait, Stephen—perfectly aware of his advantageous position in Oxford—did not take it.

Matilda's escape

David Crouch

Sir David Lance Crouch (23 June 1919 – 18 February 1998) was a British Conservative politician.

Crouch was educated at University College School, London and became a marketing consultant. He contested Leeds West in 1959, and served as Memb ...

and accompanied by four knights—escaped from St George's Tower

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined medieval castle on the western side of central Oxford in Oxfordshire, England. Most of the original moated, wooden motte and bailey castle was replaced in stone in the late 12th or early 13th century ...

one night in early December. She managed this, says J. O Prestwich, because, due to the duration of the siege, elements within Stephen's army had "deserted and others grew slack". Matilda took advantage of the weakened siege; she may have been assisted by treason within Stephen's army. If not treachery, says Davis, then certainly carelessness. In any case, he goes on, it prevented Stephen from achieving his primary aim: to win the war in one fell swoop. Matilda's escape to Wallingford contributed to her reputation for luck, which was seen as verging on the miraculous. The contemporary chronicler of the ''Gesta Stephani''—who was highly partisan to Stephen—wrote how: Matilda's escape was, true to her reputation, embroidered by contemporaries, who asked many questions as to how she had managed it. The chroniclers tried to answer them, embellishing as they did. It was the last, and probably most dramatic event of Matilda's career, a career punctuated with dramatic events. It is also the final chapter in William of Malmsbury's '' Historiae Novellae''; he was the first to suppose that she escaped by way of a postern gate and walked to Abingdon. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

''—itself relying heavily on Malmsbury—adds the possibility that she had descended from the walls by rope. The ''Gesta Stephani'' adds that not only was there thick snow but the river had frozen. Henry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon ( la, Henricus Huntindoniensis; 1088 – AD 1157), the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-century English historian and the author of ''Historia Anglorum'' (Medieval Latin for "History of the English"), ...

then garnishes the whole with the escapees' white cloaks. Edmund King has suggested that many of these explanations can be traced to other, often mythological or biblical events that would have been a point of reference for ecclesiastical chroniclers. They suggested that she had climbed down a rope out of her window (but, says King, "this was the manner of St Paul's escape from his enemies at Damascus"), that she had walked on water to cross Castle Mill Stream

Castle Mill Stream is a backwater of the River Thames in the west of Oxford, England. It is 5.5 km long.

Course

The stream leaves the main course of the River Thames at the south end of Port Meadow, immediately upstream of Medley Foo ...

("but this sounds more like the Israelites crossing the Red Sea than the traversing of an established thoroughfare", and the Thames may well have been frozen), according to Henry of Huntingdon, wrapped in a white shawl as camouflage against the snow. This was not achieved without alerting the Stephen's guards: they were not asleep, and as she slipped out, there was the sound of trumpets and men's shouting, their voices carrying through the frosty air" as Matilda and her knights slipped through Stephen's ranks. There had been a recent snowfall, which shielded her from her enemies but also hindered her passage. However precisely the escape was achieved, says Edmund King, it had clearly been thoroughly planned. The castle surrendered the day after Matilda's escape, and Stephen installed his own garrison. The siege had lasted over two and a half months.

Having made "the last and most remarkable of her escapes", says King, Matilda and her companions made their way—or "fled ignominiously", he suggests—to Abingdon where they collected horses and supplies, and then further to Wallingford, where they could rely on the support of Fitz Count, and where they met up with Gloucester. Stephen, meanwhile, took advantage of Gloucester's presence in Wallingford to make an (unsuccessful) attempt to recapture Wareham, which the earl had refortified after recapturing it.

Aftermath

Oxford has been described as Stephen's "key target" of 1142, andDavid Crouch

Sir David Lance Crouch (23 June 1919 – 18 February 1998) was a British Conservative politician.

Crouch was educated at University College School, London and became a marketing consultant. He contested Leeds West in 1959, and served as Memb ...

suggests that the loss of Oxford was tactically such a disaster as to be Matilda's Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stalingrád, label=none; ) ...

: "A final redoubt from which retreat would signal the beginning of the end for her cause." Stephen, says the ''Gesta Stephani'', now controlled most of the region and commanded the Thames Valley. He already controlled the capital and the south-east; now, says Poole, "all hopes of Angevin success eastward of the upper Thames valley" were dashed. Matilda's escape was, in itself, not a victory—if anything, says King, it highlighted the fragility of her position—and by the end of the year, the Angevin cause was, in Crouch's words, "on the ropes" and what remained of its army demoralised. This, he says, is evidenced by the fact that even though the Earl of Gloucester had returned from Normandy in late October, it took him until December to re-establish himself in his Dorsetshire heartlands, as he wanted to reassert his control over the whole Dorset coast. Wallingford was now the sole Angevin possession outside of the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Glouc ...

; Stephen, however—although waging what Barlow has described as a "brilliant tactical campaign, distinguished by personal bravery"—had also lost the momentum he had built up since his release from captivity, and had missed his last chance to end the war decisively, as he had planned, with Matilda's capture. On her arrival in the west, her party set to work consolidating what it still held, being by now unable to regain lost lands. Popular rumour held that Matilda made a vow, following her escape, to found a new Cistercian Abbey. David Crouch, though, suggests that she made this up years later in order to justify policy, and Geoffrey White notes that she did not endow an abbey until 1150, when she committed, "at the suggestion of the Archbishop of Rouen, to co-operate in the founding of Le Valasse". Stephen's exact movements after the siege are hard to establish; Oxford Castle dominated the surrounding countryside, and he probably took advantage of his new-found lordship to spend considerable time and resources subduing the countryside around Oxford. After all, says Emilie Amt, in the county generally, "far more important than the Angevins' one-time foothold here were the Angevin loyalties of many Oxfordshire barons". Stephen knew Matilda had fled to Wallingford after her escape, but made no effort to stop her. Stephen had attempted to besiege the castle in 1139, Fitz Count had "strengthened the already impregnable castle" over the years, as well as having sufficient provisions to hold out for several years, which Stephen had discovered to his cost: his siege had broken up within weeks. Stephen clearly did not wish to attempt a second assault. The King is known to have attended a

Stephen's exact movements after the siege are hard to establish; Oxford Castle dominated the surrounding countryside, and he probably took advantage of his new-found lordship to spend considerable time and resources subduing the countryside around Oxford. After all, says Emilie Amt, in the county generally, "far more important than the Angevins' one-time foothold here were the Angevin loyalties of many Oxfordshire barons". Stephen knew Matilda had fled to Wallingford after her escape, but made no effort to stop her. Stephen had attempted to besiege the castle in 1139, Fitz Count had "strengthened the already impregnable castle" over the years, as well as having sufficient provisions to hold out for several years, which Stephen had discovered to his cost: his siege had broken up within weeks. Stephen clearly did not wish to attempt a second assault. The King is known to have attended a legatine council A legatine council or legatine synod is an ecclesiastical council or synod that is presided over by a papal legate.Robinson ''The Papacy'' p. 150

According to Pope Gregory VII, writing in the ''Dictatus papae'', a papal legate "presides over all b ...

meeting in London in spring the following year, and around the same time returned to Oxford to consolidate his authority in the region. Stephen attempted a counter attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

, but was roundly beaten at the Battle of Wilton

The Battle of Wilton was a battle of the civil war in England known as The Anarchy. It was fought on 1 July 1143The date is from Gervase of Canterbury (Davis, p.72n; Crouch, p.207), but Gervase only began writing his chronicle around 1188 (Dav ...

the following year. Oxford, though, remained in the king's possession with William de Chesney

William de Chesney (flourished 1142–1161) was an Anglo-Norman magnate during the reign of King Stephen of England (reigned 1135–1154) and King Henry II of England (reigned 1154–1189). Chesney was part of a large family; one of his brothers ...

as constable; in 1155, the sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

, Henry de Oxford, was granted £7 to assist with the rebuilding of Oxford, following its "wasting by Stephen's army" 13 years earlier.

Matilda made her way to Devizes Castle, where she was to spend the rest of her campaign in England, and young Henry—whose role was to provide "some small measure of male legitimacy to his mother's struggle", suggested Martin Aurell—spent the next few months in Bristol Castle before returning to his father in France. Many of those that had lost lands in the regions held by the king travelled west to take up patronage from Matilda. With the end of the siege of Oxford, says Stringer, the military situation became generally static, "and would remain thus until the end of the war", which was to continue, in Cronne's words, as a "chess-like war of castle sieges". Both sides were, and continued to be, crippled by a combination of the massive cost of warfare and inefficient methods of raising revenue. Matilda left England in 1148; Stephen died in 1154, and, under the terms of the Treaty of Wallingford

The Treaty of Wallingford, also known as the Treaty of Winchester or the Treaty of Westminster, was an agreement reached in England in the summer of 1153. It effectively ended a civil war known as '' the Anarchy'' (1135–54), caused by a dispute ...

signed the previous year, Henry, Duke of Normandy, ascended the English throne as King Henry II.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refendOxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

History of Oxford

Stephen, King of England

Empress Matilda

The Anarchy

1142 in England

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

Military history of Oxfordshire