Siege of Limerick (1922) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish Free State offensive of July–September 1922 was the decisive military stroke of the Irish Civil War. It was carried out by the National Army of the newly created

In

In

Republicans considered Waterford to be the eastern strongpoint of the Munster Republic; however, it too was taken by a Free State column equipped with armour and artillery between 18 July and 20 July. The city was held by the IRA Waterford Brigade, and a unit from Cork city under the overall commandant of Colonel Commandant Pax Whelan and flying column leader

Republicans considered Waterford to be the eastern strongpoint of the Munster Republic; however, it too was taken by a Free State column equipped with armour and artillery between 18 July and 20 July. The city was held by the IRA Waterford Brigade, and a unit from Cork city under the overall commandant of Colonel Commandant Pax Whelan and flying column leader

The Free State's forces took the south and west of Ireland with landings from the sea. Seaborne landings were the first proposed by

The Free State's forces took the south and west of Ireland with landings from the sea. Seaborne landings were the first proposed by

The Irish Story The anti-Treaty IRA Attack on Dundalk

/ref> Nowhere, however, did the Republicans manage to re-take any territory lost on the first two months of fighting. Moreover, with the exception of county Kerry and a few other localities, the anti-treaty guerrilla campaign failed to gather momentum and by 1923, was largely reduced to small scale attacks and acts of sabotage. It took eight months of intermittent guerrilla warfare after the fall of Cork before the war was brought to an end, with victory for the Free State government. In April 1923, Liam Lynch was killed. His successor as anti-Treaty commander, Frank Aiken, called a ceasefire on 30 April and a month later, ordered his men to "dump arms" and go home. The intervening period was marked by the death of leaders formerly allied in the cause of Irish independence. Commander-in-Chief Michael Collins was killed in an ambush by anti-treaty republicans at Béal na mBláth, near his home in

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

against anti-treaty strongholds in the south and southwest of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

At the beginning of the Civil War in June 1922, the Irish Free State government, composed of the leadership faction who had accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, held the capital city of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

, where its armed forces were concentrated and some other areas of the midlands and north. The new National Army was composed of those units of the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

loyal to them, plus recent recruits, but was, at the start of the war, still relatively small and poorly armed.

Much of the rest of the country, particularly the south and west, was outside of its control and in the hands of the anti-Treaty elements of the IRA, who did not accept the legitimacy of the new state and who asserted that the Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

, created in 1919, was the continuing legitimate all-island state. This situation was rapidly brought to an end in July and August 1922, when the commander-in-chief of the Free State forces, Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

, launched the offensive.

The offensive re-took the major towns for the Free State Government and marked the end of the conventional phase of the conflict. The offensive was followed by a 10-month period of guerrilla warfare until the republican side was defeated.

Munster Republic

The civil war started inDublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

, with a week of street fighting from 28 June to 5 July 1922 in which the Free State's forces secured the Irish capital from anti-Treaty IRA troops who had occupied several public buildings. With Dublin in pro-treaty hands, the conflict spread throughout the country, with anti-Treaty forces holding Cork, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

and Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

as part of the self-styled " Munster Republic". They also held most of the west of Ireland. The Free State, on the other hand, after its taking of Dublin, controlled only of the eastern part of its territory.

However, the Anti-Treaty side were not equipped to wage conventional war

Conventional warfare is a form of warfare conducted by using conventional weapons and battlefield tactics between two or more states in open confrontation. The forces on each side are well-defined and fight by using weapons that target primari ...

, lacking artillery and armoured units, both of which the Free State obtained from the British. This meant that Liam Lynch, the Chief of Staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA, hoped to act purely on the defensive, holding the "Munster Republic" long enough to prevent the foundation of the Free State and forcing the re-negotiation of the Treaty. Lynch's strategy was bitterly criticised by other anti-Treaty officers, such as Ernie O'Malley

Ernest Bernard Malley ( ga, Earnán Ó Máille; 26 May 1897 – 25 March 1957) was an IRA officer during the Irish War of Independence. Subsequently, he became assistant chief of staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War. O'Malley ...

and Tom Barry. O'Malley felt that the republicans, who initially outnumbered the Government forces by roughly 12,000 fighters to 8,000 (and who had the bulk of the experienced fighters from the preceding Irish War of Independence), should have seized the initiative, taken the major cities and presented the British with a resurrected Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

as a ''fait accompli''.O'Malley The Singing Flame pp. 140–141

The thinking behind O'Malley's analysis was that time was on the side of the Free State as they could only get stronger, through supplies from the British, revenue raised from taxation and recruitment into their army, while the Republican side had only very limited means of re-supply of men, money or arms. O'Malley wrote: "Tan War experience would no longer suffice as this type of fighting would need semi-open warfare. Columns would have to be larger and their men trained to take the offensive in driving the enemy out of towns and cities... Unless our Connacht and Munster men moved on to Leinster effective opposition would be broken up piecemeal and we would soon be crushed".

The leaders of the Free State government, Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, also felt that a rapid victory was essential from their point of view. To secure the withdrawal of British troops from Ireland (Collins' ultimate aim) the government would have to demonstrate its viability by suppressing what, from its point of view, was an illegal insurrection and its control all of its sovereign territory. It was with this aim in mind that they launched their offensive in July–August 1922 to re-take the south and west of the country.

Fall of Limerick

In

In Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, the outbreak of the war saw the city already occupied by both pro and anti-treaty factions. The anti-treaty IRA, largely composed of Liam Forde's Mid-Limerick Brigade and commanded by Liam Lynch, held four military barracks and most of the town. The Free State forces in the city consisted of the pro-Treaty First Western Division of the IRA under Michael Brennan and the Fourth Southern Division under Commandant General Donochadh O'Hannigan. They held the Customs House, the Jail, the Courthouse, Williams Street RIC Barracks, and Cruises Hotel. They also held the Athlunkard bridge located outside of Limerick which provided a secure means of bringing reinforcements.

Fighting broke out between them on 11 July 1922, when the first Free State reinforcements arrived from Dublin. At 7 p.m. on 11 July, the National Army opened fire on the Republican garrison holding the Ordnance Barracks. Liam Lynch left Limerick when the fighting broke out and transferred his headquarters to Clonmel.

On 17 July, General Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish military commander, police commissioner and politician. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure i ...

arrived with 150 Free State reinforcements including a Whippet Rolls-Royce armoured car, 2 Lancia armoured cars, 4 trucks with 400 rifles, 10 Lewis machine guns, 400 grenades, ammunition and an 18-pounder cannon. The 18-pounder field gun was used on 19 July to batter the Strand Barracks, which was under the command of captain Connie McNamara, into surrender.

After three days of street fighting, after midnight on 21 July, the Republicans set the Artillery (also called the ordnance barracks), castle barracks and New Barracks on fire and evacuated Limerick city. Despite the intensive street fighting in Limerick, the casualties of the combatants were relatively light; 19 bodies were left in the city morgue, twelve of whom were civilians and seven Free State soldiers. Another 87 were wounded. The Republican dead were reported in the press as thirty killed but they admitted only five. Limerick Prison, designed to hold 120 people, contained 800 prisoners by November. Following the fall of Limerick the anti treaty forces retreated through Patrickswell towards Kilmallock. There, in the Kilmallock-Bruff-Bruree triangle, would be seen some of the heaviest fighting of the war.

Free State troops take Waterford

Republicans considered Waterford to be the eastern strongpoint of the Munster Republic; however, it too was taken by a Free State column equipped with armour and artillery between 18 July and 20 July. The city was held by the IRA Waterford Brigade, and a unit from Cork city under the overall commandant of Colonel Commandant Pax Whelan and flying column leader

Republicans considered Waterford to be the eastern strongpoint of the Munster Republic; however, it too was taken by a Free State column equipped with armour and artillery between 18 July and 20 July. The city was held by the IRA Waterford Brigade, and a unit from Cork city under the overall commandant of Colonel Commandant Pax Whelan and flying column leader George Lennon

George Lennon (25 May 1900 – 20 February 1991) was an Irish Republican Army leader during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War.

Background and early Republican activities

George Gerard Lennon was born in Dungarvan, Count ...

; a total of nearly 300 men.Terence O'Reilly, Rebel Heart: George Lennon: Flying Column Commander Mercier 2009, , p175-188

In late July 1922, National Army troops under Major General John T. Prout and former East Waterford I.R. A. Commandant Paddy Paul, composed of 450 men, one 18-pounder artillery piece and 4 machine guns arrived from Kilkenny to retake the city. The republicans had chosen to defend the city along the southern bank of the river Suir

The River Suir ( ; ga, an tSiúr or ''Abhainn na Siúire'' ) is a river in Ireland that flows into the Atlantic Ocean through Waterford after a distance of .

The catchment area of the Suir is 3,610 km2.

, occupying the military barracks, the prison and the Post Office. Prout placed his artillery on Mount Misery hill overlooking their positions and bombarded the Republicans until they were forced to evacuate the barracks and prison.

However, the gun had to be brought down to Ferrybank (along the river) to fire over open sights before the Republicans abandoned the Post Office. Six more shells were fired at Ballybricken prison before it was also evacuated. Some street fighting followed before the Republicans abandoned the city and retreated westwards. Two Free State soldiers were killed in the fighting and one Republican. Five civilians were also killed.

A proposed Republican counterattack from Carrick on Suir failed to materialise.

The Free State forces under Prout went on to take Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

on 2 August, Carrick on Suir

Carrick-on-Suir () is a town in County Tipperary, Ireland. It lies on both banks of the River Suir. The part on the north bank of the Suir lies in the civil parish of "Carrick", in the historical barony of Iffa and Offa East. The part on the so ...

on 3 August and Clonmel on 10 August, effectively clearing the south midlands of Republican held positions. In taking these towns, Free State troops generally encountered only limited resistance. The Republicans, when faced with artillery, tended to retreat and burn barracks they were holding rather than try to hold them and risk heavy casualties.

At both Limerick and Waterford, the Free State's advantage in weaponry, particularly artillery, was decisive. Casualties on both sides in these actions were relatively light, although there were also some civilian casualties, since the fighting took place in the heavily populated urban centres.

Combat at Killmallock

The Free State troops under Eoin O'Duffy encountered more tenacious resistance in the countryside aroundKilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are sti ...

, south of Limerick city, when they tried to advance into republican held Munster. Eoin O'Duffy's 1,500 troops were faced with about 2,000 anti-Treaty IRA men under Liam Deasy

Liam Deasy (6 May 1896 – 20 August 1974) was an Irish Republican Army officer who fought in the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. In the latter conflict, he was second-in-command of the Anti-Treaty forces for a period in ...

, who had three armoured cars they had taken from the evacuating British troops. Deasy's men were dug in at Kilmallock, Bruree

Bruree () is a village in south-eastern County Limerick, Ireland, on the River Maigue. It takes its name from the nearby ancient royal fortress, the alternative name of which from the earliest times into the High Middle Ages was ''Dún Eochair M ...

to the northwest and Bruff to the northeast.

On 23 July Major General W.R.E. Murphy (a former British Army officer and O'Duffy's second in command) took the town of Bruff, but his poorly motivated troops lost it again the following day and 76 of them surrendered to the Republicans. The Free State troops re-took Bruff shortly afterwards, though and on 30 July, they assaulted Bruree with their best troops – the Dublin Guard

The Dublin Guard was a unit of the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and then of the Irish National Army in the ensuing Civil War.

Foundation

In May 1921 the Active Service Unit of the Irish Republican Army's Dublin Briga ...

. They took it after a five-hour fight, but only after artillery was brought up at close range to support them. Liam Deasy attempted to re-take the village on 2 August, but the attack, with three armoured cars, was beaten off.

The following day, 2,000 Free State troops advanced on Kilmallock. Fighting continued here until 5 August, despite the arrival of over 1,000 more Free State troops and more armoured cars and artillery. Deasy's anti-treaty forces were ultimately forced to retreat however, when Free State forces were landed by sea behind them in Passage West

Passage West (locally known as "Passage"; ) is a port town in County Cork, Ireland, situated on the west bank of Cork Harbour, some 10 km south-east of Cork city. The town has many services, amenities and social outlets. Passage West wa ...

and Fenit

Fenit () is a small village in County Kerry, Ireland, located on north side of Tralee Bay about west of Tralee town, just south of the Shannon Estuary. The bay is enclosed from the Atlantic by the Maharee spit which extends northwards from ...

in counties Cork and Kerry on 2 August and 8 August respectively.

When the National Army entered Kilmallock on 5 August, they found only a Republican rearguard, the remainder having already retreated in the direction of Charleville Charleville can refer to:

Australia

* Charleville, Queensland, a town in Australia

**Charleville railway station, Queensland

France

* Charleville, Marne, a commune in Marne, France

*Charleville-Mézières, a commune in Ardennes, France

** ...

. There was final rearguard action at Newcastlewest before the republican forces retreated after losing a number of men (press reports suggested 12) killed.

Fall of Cork and landing in the west

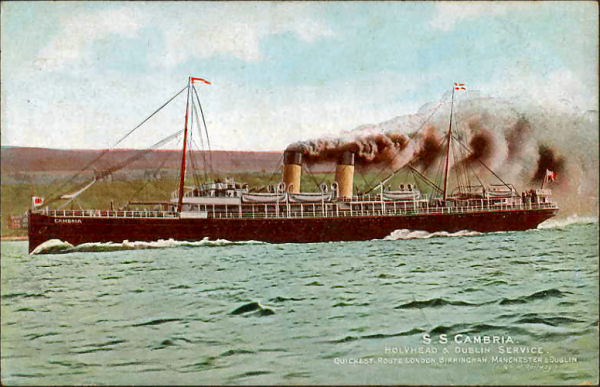

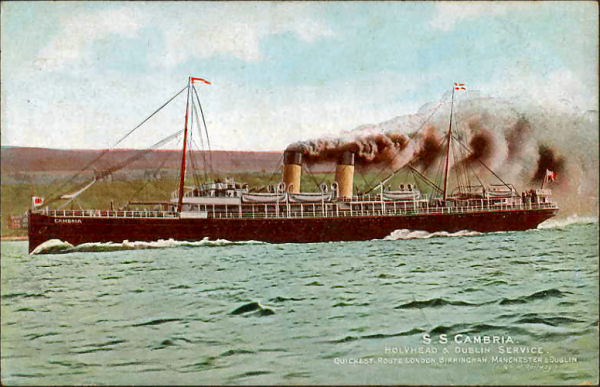

The Free State's forces took the south and west of Ireland with landings from the sea. Seaborne landings were the first proposed by

The Free State's forces took the south and west of Ireland with landings from the sea. Seaborne landings were the first proposed by Emmet Dalton

James Emmet Dalton MC (4 March 1898 – 4 March 1978) was an Irish soldier and film producer. He served in the British Army in the First World War, reaching the rank of captain. However, on his return to Ireland he became one of the senior fig ...

and then adopted by Michael Collins. Their plan was to avoid the hard fighting that would inevitably occur if they advanced overland through Republican held Munster and Connaught

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

. To this end, they commandeered several civilian passenger ships to transport troops. They were the ''Arvonia'' and the SS Lady Wicklow They were escorted by British naval vessels

The first naval landing took place at Clew Bay

Clew Bay (; ga, Cuan Mó) is a natural ocean bay in County Mayo, Republic of Ireland. It contains Ireland's best example of sunken drumlins.

The bay is overlooked by Croagh Patrick to the south and the Nephin Range mountains of North Mayo. Cla ...

in County Mayo on 24 July and helped re-take the west of Ireland for the Free State. This force, consisting of 400 Free State soldiers, one field gun and an armoured car under Christopher O'Malley, re-took the Republican held town of Westport and linked up with another Free State column under Seán Mac Eoin

Seán Mac Eoin (30 September 1893 – 7 July 1973) was an Irish Fine Gael politician and soldier who served as Minister for Defence briefly in 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, Minister for Justice from 1948 to 1951, and Chief of Staff of the Def ...

advancing from Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Ireland. Developing around a 13th century castle of the de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal point for the surrounding hinterland. W ...

. A Free State column also dispersed anti-Treaty IRA forces in Donegal in Ireland's north-west.

The largest seaborne landings took place in the south. Ships disembarked about 2,000 well equipped Free State troops into the heart of the "Munster Republic" and caused the rapid collapse of the Republican position in this province.

Paddy Daly and the Dublin Guard

The Dublin Guard was a unit of the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and then of the Irish National Army in the ensuing Civil War.

Foundation

In May 1921 the Active Service Unit of the Irish Republican Army's Dublin Briga ...

landed at Fenit

Fenit () is a small village in County Kerry, Ireland, located on north side of Tralee Bay about west of Tralee town, just south of the Shannon Estuary. The bay is enclosed from the Atlantic by the Maharee spit which extends northwards from ...

in County Kerry on 2 August and fought their way into Tralee

Tralee ( ; ga, Trá Lí, ; formerly , meaning 'strand of the Lee River') is the county town of County Kerry in the south-west of Ireland. The town is on the northern side of the neck of the Dingle Peninsula, and is the largest town in Count ...

at the cost of 9 killed and 35 wounded. They were reinforced on 3 August, by around 250 pro-treaty IRA men from County Clare

County Clare ( ga, Contae an Chláir) is a county in Ireland, in the Southern Region and the province of Munster, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council is the local authority. The county had a population of 118,81 ...

, embarked from Kilrush to Tarbert

Tarbert ( gd, An Tairbeart) is a place name in Scotland and Ireland. Places named Tarbert are characterised by a narrow strip of land, or isthmus. This can be where two lochs nearly meet, or a causeway out to an island.

Etymology

All placenames ...

in fishing boats. The Free State forces rapidly occupied the towns in the county but the Republican units in Kerry survived more or less intact and would fight a determined guerrilla campaign for the remainder of the war.

If the Munster Republic had a capital, it was Cork and the largest seaborne landings of the civil war were aimed at taking that city. Emmet Dalton led 800 troops, with two artillery pieces and armoured cars, who landed at Passage West

Passage West (locally known as "Passage"; ) is a port town in County Cork, Ireland, situated on the west bank of Cork Harbour, some 10 km south-east of Cork city. The town has many services, amenities and social outlets. Passage West wa ...

, near the city, on 8 August. A further 200 men were put ashore at Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long and narrow layout. ...

and 180 troops landed at Glandore

Glandore (, meaning ''harbour of the oak trees'') is the name of both a harbour and village in County Cork, Ireland. Glandore is located about an hour's drive south-west of Cork city.

The village has several pubs, with traditional music. It i ...

. There was some heavy fighting at Rochestown

Rochestown is a primarily residential area in Cork City, Ireland. Originally a somewhat rural area in County Cork, housing developments in the 20th and 21st centuries have connected the area to Douglas and nearby suburbs. The area was formally in ...

and Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

* Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

*Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civi ...

in which at least ten Free State and 7 Republican fighters were killed and at least 60 men on both sides were wounded, before the outnumbered and outgunned anti-treaty IRA retreated into the city. However, they did not try to continue the fighting Cork itself, partly in order to spare the civilian population, but instead burned Charles Barracks, near Kinsale, which they had been occupying, and dispersed into the countryside.

The Free State landings in Munster coincided with an attempt by anti-Treaty guerrillas to isolate Dublin by destroying all the road and rail bridges leading into the city. However this operation was a complete failure with over 180 republicans being captured at a cost of only two Free State soldiers wounded.

On 10 August, Free State troops entered Cork city unopposed, the last city to fall in the "Munster Republic". Liam Lynch, the Republican commander in chief abandoned Fermoy

Fermoy () is a town on the River Blackwater in east County Cork, Ireland. As of the 2016 census, the town and environs had a population of approximately 6,500 people. It is located in the barony of Condons and Clangibbon, and is in the Dá ...

, the last Republican held town, the following day. In leaving Fermoy, he issued an order to troops under his command to stop trying to hold fixed positions and to form flying columns to pursue guerrilla warfare.

Aftermath

The Free State offensive of July–August 1922 all but ended the Anti-Treaty side's chances of winning the war. The Republicans failed, with the exception of a brief stand around Killmallock, to resist the advance of Free State troops anywhere in the country. While some of this can be put down to the Free State's advantages in arms and equipment, the Republican leadership under Liam Lynch also failed to devise any coherent military strategy, allowing their positions to be picked off one by one. On top of this, most of the Republican fighters showed little appetite for the civil war, generally retreating before National Army attacks rather than putting up determined resistance. In part, this shows a lack of discipline and training for conventional warfare, but there was also a general reluctance on both sides to fight against former comrades from the War of Independence. One, for instance Tom Maguire said that, 'in the beginning our men would not kill the reeStaters', while anotherGeorge Gilmore

George Frederick Gilmore (5 May 1898 – 1985) was a Protestant Irish republican and communist who became an Irish Republican Army leader during the 1920s and 1930s. During his period of influence, Gilmore attempted to shift the IRA to the polit ...

said, 'I had not a desire to kill the enemy, all of our man had it eluctanceto some extent and the officers who were operating against us were our own former friends'.

The Free State Government's victories in the major towns inaugurated a period of inconclusive guerrilla warfare. Anti-Treaty IRA units held out in areas such as the western part of counties Cork and Kerry in the south, county Wexford in the east and counties Sligo and Mayo Mayo often refers to:

* Mayonnaise, often shortened to "mayo"

* Mayo Clinic, a medical center in Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Mayo may also refer to:

Places

Antarctica

* Mayo Peak, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

* Division of Mayo, an Aust ...

in the west. Sporadic fighting also took place around Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

, where Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was chief of staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the Irish Civil War. Aiken later served as Tánaiste from 1965 to 1969 and Minister ...

and the Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army

The Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army operated in an area covering parts of counties Louth, Armagh, Monaghan, and Down during the Irish War of Independence and Civil War. Frank Aiken was commander and Pádraig Quinn was the q ...

were based. Aiken originally wanted to stay neutral, but was arrested by Free State troops along with 400 of his men on 16 July 1922. They subsequently broke out of prison in Dundalk and temporarily re-took the town in a guerrilla raid./ref> Nowhere, however, did the Republicans manage to re-take any territory lost on the first two months of fighting. Moreover, with the exception of county Kerry and a few other localities, the anti-treaty guerrilla campaign failed to gather momentum and by 1923, was largely reduced to small scale attacks and acts of sabotage. It took eight months of intermittent guerrilla warfare after the fall of Cork before the war was brought to an end, with victory for the Free State government. In April 1923, Liam Lynch was killed. His successor as anti-Treaty commander, Frank Aiken, called a ceasefire on 30 April and a month later, ordered his men to "dump arms" and go home. The intervening period was marked by the death of leaders formerly allied in the cause of Irish independence. Commander-in-Chief Michael Collins was killed in an ambush by anti-treaty republicans at Béal na mBláth, near his home in

County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns a ...

, on 22 August 1922. Arthur Griffith, the Free State president died of a brain haemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

ten days before. The Free State government was subsequently led by William Cosgrave and the Free State Army by General Richard Mulcahy

Richard James Mulcahy (10 May 1886 – 16 December 1971) was an Irish Fine Gael politician and army general who served as Minister for Education from 1948 to 1951 and 1954 to 1957, Minister for the Gaeltacht from June 1956 to October 1956, ...

. On the Republican side, leaders such as Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows

William Joseph Mellows ( ga, Liam Ó Maoilíosa, 25 May 1892 – 8 December 1922) was an Irish republican and Sinn Féin politician. Born in England to an English father and Irish mother, he grew up in Ashton-under-Lyne before moving to Irelan ...

, Joe McKelvey

Joseph McKelvey (17 June 1898 – 8 December 1922) was an Irish Republican Army officer who was executed during the Irish Civil War. He participated in the anti-Treaty IRA's repudiation of the authority of the Dáil (civil government of the Iri ...

, Erskine Childers and Liam Lynch lost their lives in the guerrilla phase of the war.

This phase of the war, much more than the conventional phase, developed into a vicious cycle of revenge killings and reprisals as the Republicans assassinated pro-treaty politicians and the Free State responded with the execution of Republican prisoners. (See Executions during the Irish Civil War

The executions during the Irish Civil War took place during the guerrilla phase of the Irish Civil War (June 1922 – May 1923). This phase of the war was bitter, and both sides, the government forces of the Irish Free State and the anti-Treat ...

).

See also

* Battle of Dublin *Timeline of the Irish Civil War

This is a timeline of the Irish Civil War, which took place between June 1922 and May 1923. It followed the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State as an entity independent from the U ...

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Irish Free State Offensive Battles of the Irish Civil War Military history of Ireland 1922 in Ireland June 1922 events July 1922 events August 1922 events