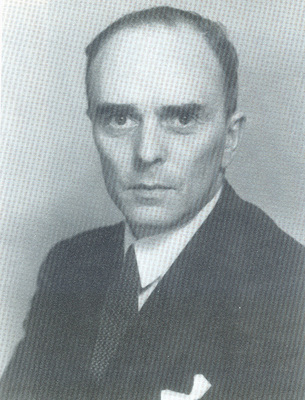

Seán MacBride on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seán MacBride (26 January 1904 – 15 January 1988) was an Irish

In 1946, MacBride founded the republican/socialist party

In 1946, MacBride founded the republican/socialist party

In 1929 an Irish section of the League Against Imperialism was formed and MacBride served as its secretary.

MacBride served as the International Chairman of

In 1929 an Irish section of the League Against Imperialism was formed and MacBride served as its secretary.

MacBride served as the International Chairman of

Clann na Poblachta

Clann na Poblachta (; "Family/Children of the Republic") was an Irish republican political party founded in 1946 by Seán MacBride, a former Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army.

Foundation

Clann na Poblachta was officially launched on ...

politician who served as Minister for External Affairs from 1948 to 1951, Leader of Clann na Poblachta from 1946 to 1965 and Chief of Staff of the IRA from 1936 to 1937. He served as a Teachta Dála

A Teachta Dála ( , ; plural ), abbreviated as TD (plural ''TDanna'' in Irish, TDs in English), is a member of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament). It is the equivalent of terms such as ''Member of Parl ...

(TD) from 1947 to 1957.

Rising from a domestic Irish political career, he founded or participated in many international organisations of the 20th century, including the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

, the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

and Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and s ...

. He received the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

in 1974, the Lenin Peace Prize for 1975–1976 and the UNESCO Silver Medal for Service in 1980.

Early life

MacBride was born inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in 1904, the son of Major John MacBride

John MacBride (sometimes written John McBride; ga, Seán Mac Giolla Bhríde; 7 May 1868 – 5 May 1916) was an Irish republican and military leader. He was executed by the British government for his participation in the 1916 Easter R ...

Saturday Evening Post; 23 April 1949, Vol. 221 Issue 43, pp. 31–174, 5p and Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne MacBride ( ga, Maud Nic Ghoinn Bean Mhic Giolla Bhríghde; 21 December 1866 – 27 April 1953) was an English-born Irish republican revolutionary, suffragette and actress. Of Anglo-Irish descent, she was won over to Irish nationalism ...

. His first language was French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, and he retained a French accent in the English language for the rest of his life. MacBride first studied at the Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague

The Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague (Franklin), founded in 1894, is a highly selective Roman Catholic, Jesuit school in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It is regarded as the most prestigious French private school and has been ranked #1 lycée in ...

, and remained in Paris until his father's execution by the British for his involvement in the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

, when he was sent to school at Mount St Benedict's, Gorey, County Wexford

County Wexford ( ga, Contae Loch Garman) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was based on the historic Gaelic territory of Hy Kinsella (''Uí C ...

in Ireland, and briefly at the Downside School.

MacBride first became involved in politics during the 1918 Irish general election

The 1918 Irish general election was the part of the 1918 United Kingdom general election which took place in Ireland. It is now seen as a key moment in modern Irish history because it saw the overwhelming defeat of the moderate nationalist Iri ...

in which he was active for Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gr ...

. The following year in 1919, aged 15, he lied about his age to join the Irish Volunteers, which fought as part of the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

, and took part in the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. He opposed the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

and was imprisoned by the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

.

On his release in 1924, MacBride studied law at University College Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 33,284 student ...

and resumed his IRA activities.Jordan (1993), p. 41. He worked briefly for Éamon de Valera as his personal secretary, travelling with him to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to meet various dignitaries.

In January 1925, on his twenty-first birthday, MacBride married Catalina "Kid" Bulfin, a woman four years his senior who shared his political views.Jordan (1993), p. 42. Bulfin was the daughter of the Irish nationalist publisher and travel-writer William Bulfin

William Bulfin (1 November 1863 – February 1910) was an Irish, and later Argentine, author, journalist, newspaper editor and publisher. He was the fourth son in a family of nine boys and one girl, the children of William Bulfin, of Derrinlough, ...

.

Before returning to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

in 1927, where he became the IRA's Director of Intelligence, MacBride worked as a journalist in Paris and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

According to historians Tom Mahon and James J. Gillogly, recently deciphered IRA messages from the 1920s reveal that the organisation's two main sources of funding were Clan na Gael and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. The messages further reveal that MacBride, before becoming IRA Director of Intelligence, was involved in the espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

activities in Great Britain of GRU spymaster

A spymaster is the person that leads a spy ring, or a secret service (such as an intelligence agency).

Historical spymasters

See also

*List of American spies

This is a list of spies who engaged in direct espionage. It includes Americans s ...

Walter Krivitsky, whom ciphered IRA communications referred to only by the code name "James".

In addition to supplying the USSR with detailed information on Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

ships and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

airplane engines, MacBride provided Soviet agents with "a brief specification and a complete drawing" of ASDIC, an early sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on o ...

detection system for enemy submarines during wartime, at a covert meeting in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

during the autumn of 1926. MacBride also assisted the GRU by providing forged passports to Soviet intelligence operatives who were at risk of capture.

In October 1926, MacBride sent a ciphered report from Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

to his IRA superiors about Soviet counterfeiting

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value tha ...

operations, saying, "Several bad Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

notes have been passed here lately. These are said to emanate from Russia."

Soon after his return to Dublin in 1927, he was arrested and charged with the murder of politician Kevin O'Higgins

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins ( ga, Caoimhghín Críostóir Ó hUigín; 7 June 1892 – 10 July 1927) was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice from 1922 to 1927, Minister for External ...

, who had been assassinated near his home in Booterstown

Booterstown () is a coastal suburb of the city of Dublin in Ireland. It is also a townland and civil parish in the modern county of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown. It is situated about south of Dublin city centre.

History

There is some debate on ...

, County Dublin

"Action to match our speech"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Dublin.svg

, map_alt = map showing County Dublin as a small area of darker green on the east coast within the lighter green background of ...

. At his trial, however, Cumann na nGaedheal

Cumann na nGaedheal (; "Society of the Gaels") was a political party in the Irish Free State, which formed the government from 1923 to 1932. In 1933 it merged with smaller groups to form the Fine Gael party.

Origins

In 1922 the pro-Treat ...

politician Bryan Cooper testified as a witness for the defence that, at the time of Kevin O'Higgins' murder, both he and MacBride had been aboard a ferry travelling from Britain to Ireland. MacBride was then charged with being a subversive and interned in Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, Príosún Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History ...

.Jordan (1993), p. 47.

In September 1927, Krivitsky sent the IRA a message from Amsterdam, demanding to see MacBride immediately, claiming to have a "present" he was anxious to give away, and naming a cafe where the meeting could take place. As MacBride was then imprisoned in Dublin, the IRA's chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, Moss Twomey, replied that the request was "rather awkward and impossible to fulfill at the present". In response, Twomey and two other senior IRA members travelled to Amsterdam and met with Krivitsky instead.

Towards the end of the 1920s, after many supporters had left to join Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christia ...

, some members of the IRA started pushing for a more left-wing agenda. After the IRA Army Council voted down the idea, MacBride launched a new movement, Saor Éire

Saor Éire (; meaning 'Free Ireland') was a far-left political organisation established in September 1931 by communist-leaning members of the Irish Republican Army, with the backing of the IRA leadership. Notable among its founders was Peada ...

("Free Ireland"), in 1931. Although it was a non-military organisation, Saor Éire was declared unlawful along with the IRA, Cumann na mBan and nine other bodies. MacBride, meanwhile, became the security services' number-one target.Jordan (1993), p. 57.

In 1936, the IRA's chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

Moss Twomey was sent to prison for three years; he was replaced by MacBride. At the time, the movement was in a state of disarray, with conflicts between several factions and personalities. Tom Barry was appointed chief of staff to head up a military operation against the British, an action with which MacBride did not agree.Jordan (1993), p. 70.

In 1937, MacBride was called to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

. He then resigned from the IRA when the Constitution of Ireland was enacted later that year. As a barrister, MacBride frequently defended IRA prisoners of the state ( Thomas Hart & Patrick McGrath). MacBride was unsuccessful in preventing the 1944 death by hanging of Charlie Kerins, who had been convicted based on fingerprint evidence of the 1942 ambush and murder of Garda Detective Sergeant

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other ...

Denis O'Brien. In 1946, during the inquest into the death of Seán McCaughey

Seán McCaughey (Irish: Seán Mac Eóchaidh) (1915 – 11 May 1946) was an Irish Republican Army leader in the 1930s and 1940s and hunger striker.

Background

McCaughey was born in Aughnacloy, County Tyrone in 1915 and in 1921 his family moved ...

, MacBride embarrassed the Irish State by forcing them to admit that conditions in Portlaoise Prison were inhumane.

Clann na Poblachta

In 1946, MacBride founded the republican/socialist party

In 1946, MacBride founded the republican/socialist party Clann na Poblachta

Clann na Poblachta (; "Family/Children of the Republic") was an Irish republican political party founded in 1946 by Seán MacBride, a former Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army.

Foundation

Clann na Poblachta was officially launched on ...

. He hoped it would replace Fianna Fáil as Ireland's major political party. In October 1947, he won a seat in Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

at a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

in the Dublin County constituency. On the same day, Patrick Kinane also won the Tipperary by-election for Clann na Poblachta.Jordan (1993), pp. 86–98

However, at the 1948 general election Clann na Poblachta won only ten seats. The party joined with Fine Gael

Fine Gael (, ; English: "Family (or Tribe) of the Irish") is a liberal-conservative and Christian-democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of Dáil É ...

, the Labour Party, the National Labour Party, Clann na Talmhan

Clann na Talmhan (, "Family/Children of the land"; formally known as the ''National Agricultural Party'') was an Irish agrarian political party active between 1939 and 1965.

Formation and growth

Clann na Talmhan was founded on 29 June 1939 in ...

and several independents to form the First Inter-Party Government

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

with Fine Gael TD John A. Costello

John Aloysius Costello (20 June 1891 – 5 January 1976) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 1948 to 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, Leader of the Opposition from 1951 to 1954 and from 1957 to 1959, and Attorney General ...

as Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the of ...

. Richard Mulcahy was the Leader of Fine Gael

The Leader of Fine Gael is the most senior politician within the Fine Gael political party in Ireland. Since 2 June 2017, the office has been held by Leo Varadkar following the resignation of Enda Kenny.

The deputy leader of Fine Gael is Simo ...

, but MacBride and many other Irish Republicans had never forgiven Mulcahy for his role in carrying out 77 executions under the government of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

in the 1920s during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

. To gain the support of Clann na Poblachta, Mulcahy stepped aside in favour of Costello. Two Clann na Poblachta TDs joined the cabinet; MacBride became Minister for External Affairs while Noël Browne

Noël Christopher Browne (20 December 1915 – 21 May 1997) was an Irish politician who served as Minister for Health from 1948 to 1951 and Leader of the National Progressive Democrats from 1958 to 1963. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from ...

became Minister for Health.

On his ministerial accession, MacBride sent a telegram to Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

offering:

*"...to repose at the feet of Your Holiness the assurance of our filial loyalty and our devotion to Your August Person, as well as our firm resolve to be guided in all our work by the teaching of Christ and to strive for the attainment of a social order in Ireland based on Christian principles".

At MacBride's suggestion, Costello nominated the northern Protestant Denis Ireland

Denis Liddell Ireland (29 July 1894 – 23 September 1974) was an Irish essayist and political activist. A northern Protestant, after service in the First World War he embraced the cause of Irish independence. He also advanced the social credit id ...

to Seanad Éireann, the first resident of Northern Ireland to be appointed as a member of the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas (, ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the bicameral parliament of Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of:

*The President of Ireland

*The two houses of the Oireachtas ( ga, Tithe an Oireachtais):

** Dáil Éireann ...

. While a Senator (1948–1951), Ireland was Irish representative to the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

assisting MacBride in the leading role he was to play in securing acceptance of the European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

—signed in Rome on 4 November 1950. In 1950, MacBride was president of the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Council of Europe, and he was vice-president of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC, later OECD) in 1948–1951. He was responsible for Ireland not joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two Nor ...

(NATO).Jordan (1993), p. 115

He was instrumental in the repeal of the External Relations Act and the passing of the Republic of Ireland Act which came into force in 1949. It declared that Ireland may officially be described as the Republic of Ireland and that the President of Ireland

The president of Ireland ( ga, Uachtarán na hÉireann) is the head of state of Ireland and the supreme commander of the Irish Defence Forces.

The president holds office for seven years, and can be elected for a maximum of two terms.Constitu ...

had the executive authority of the state in its external relations.

In 1951, MacBride controversially ordered Noël Browne to resign as a minister over the Mother and Child Scheme

The Mother and Child Scheme was a healthcare programme in Ireland that would later become remembered as a major political crisis involving primarily the Irish Government and Roman Catholic Church in the early 1950s.

The scheme was referred to as ...

after it was attacked by the Irish Catholic hierarchy and the Irish medical establishment.Jordan (1993), pp. 125–140Whatever the merits of the scheme, or of Browne, MacBride concluded in a Cabinet memorandum:

:"Even if, as Catholics, we were prepared to take the responsibility of disregarding he Hierarchy'sviews, which I do not think we can do, it would be politically impossible to do so . . . We are dealing with the considered views of the leaders of the Catholic Church to which the vast majority of our people belong; these views cannot be ignored."

Also in 1951, Clann na Poblachta was reduced to two seats after the general election. MacBride kept his seat and was re-elected again in 1954. Opposing the internment of IRA suspects during the Border Campaign (1956–1962), he contested both the 1957 and 1961

Events January

* January 3

** United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces that the United States has severed diplomatic and consular relations with Cuba (Cuba–United States relations are restored in 2015).

** Aero Flight 311 (K ...

general elections but failed to be elected both times. He then retired from politics and continued practising as a barrister.

International politics

In 1929 an Irish section of the League Against Imperialism was formed and MacBride served as its secretary.

MacBride served as the International Chairman of

In 1929 an Irish section of the League Against Imperialism was formed and MacBride served as its secretary.

MacBride served as the International Chairman of Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and s ...

from 1961 until 1975. He was Secretary-General of the International Commission of Jurists

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) is an international human rights non-governmental organization. It is a standing group of 60 eminent jurists—including senior judges, attorneys and academics—who work to develop national and inte ...

from 1963 to 1971. Following this, he was also elected Chair (1968–1974) and later President (1974–1985) of the International Peace Bureau in Geneva. He was vice-president of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation from 1948 to 1951 and President of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

in 1950. He was also involved in the International Prisoners of Conscience Fund and was appointed the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems in 1977.Jordan (1993), pp. 157–165

He drafted the constitution of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

(OAU); and also the first constitution of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

(the first UK African colony to achieve independence) which lasted for nine years until the coup of 1966.

In 1966, the US government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

reported that he had been involved with a Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) funding operation.

MacBride was a signatory of the Convention for European Economic Co-operation, the Convention for the Protection of War Victims (1949) and the European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

. He also played a part in drawing up the constitutions of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

and Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

.

Some of MacBride's appointments to the United Nations System included:

*Assistant Secretary-General

An under-secretary-general of the United Nations (USG) is a senior official within the United Nations System, normally appointed by the General Assembly on the recommendation of the secretary-general for a renewable term of four years. Under-s ...

*President of the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

* High Commissioner for Namibia, in which capacity he created the United Nations Institute for Namibia

*President of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

's International Commission for the Study of Communications Problems, which produced the controversial 1980 MacBride report.

Human rights

Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, MacBride worked for human rights worldwide. He took an Irish case to theEuropean Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR or ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that ...

after hundreds of suspected IRA members were interned without trial in the Republic of Ireland in 1958. He was among a group of lawyers who founded JUSTICE

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

—the UK-based human rights and law reform organisation—initially to monitor the show trials after the 1956 Budapest uprising, but which later became the UK section of the International Commission of Jurists

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) is an international human rights non-governmental organization. It is a standing group of 60 eminent jurists—including senior judges, attorneys and academics—who work to develop national and inte ...

. He was active in a number of international organisations concerned with human rights, among them the Prisoners of Conscience Appeal Fund (trustee).

In 1973, he was elected by the General Assembly to the post of High Commissioner for Namibia, with the rank of Assistant Secretary-General. The actions of his father John MacBride in leading the Irish Transvaal Brigade (also known as MacBride's Brigade) on the side of the Boer republics against the British in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

gave MacBride a unique access to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

's apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

government. In 1977, he was appointed president of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, set up by UNESCO. In 1980 he was appointed Chairman of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

. MacBride supported the Dunnes Stores Strike

On 19 July 1984, Mary Manning, a shop worker in the Henry Street, Dublin (Ireland) outlet of Dunnes Stores, refused to handle the sale of grapefruit from South Africa. Her union, IDATU, had issued directions to its members not to handle South Afr ...

and attended at least one of their gatherings in May 1985.

MacBride's work was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

(1974)United Nations Chronicle, Sep95, Vol. 32 Issue 3, p. 14, 2/5p, 1c; (AN 9511075547) as a man who "mobilised the conscience of the world in the fight against injustice". He later received the Lenin Peace Prize (1975–76) and the UNESCO Silver Medal for Service (1980). He received the Lenin Peace Prize for his opposition to what MacBride referred to as "this absolutely obscene arms race." He was one of only two to win both the Lenin and Nobel peace prizes, the other being Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

.

During the 1980s, he initiated the Appeal by Lawyers against Nuclear War which was jointly sponsored by the International Peace Bureau and the International Progress Organization

The International Progress Organization (IPO) is a Vienna-based think tank dealing with world affairs. As an international non-governmental organization (NGO) it enjoys consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations ...

. In close co-operation with Francis Boyle and Hans Köchler of the International Progress Organization

The International Progress Organization (IPO) is a Vienna-based think tank dealing with world affairs. As an international non-governmental organization (NGO) it enjoys consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations ...

he lobbied the General Assembly for a resolution demanding an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

on the legality of nuclear arms. The Advisory Opinion on the ''Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons'' was eventually handed down by the ICJ in 1996.

In 1982, MacBride was chairman of the International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon. The other members were Richard Falk

Richard Anderson Falk (born November 13, 1930) is an American professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, and Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor's Chairman of the Board of Trustees. In 2004, he was listed as the aut ...

, Kader Asmal

Abdul Kader Asmal (8 October 1934 – 22 June 2011) was a South African politician. He was a professor of human rights at the University of the Western Cape, chairman of the council of the University of the North and vice-president of the ...

, Brian Bercusson, Géraud de la Pradelle, and Stefan Wild. The commission's report, which concluded that "the government of Israel has committed acts of aggression contrary to international law", was published in 1983 under the title ''Israel in Lebanon''.

He proposed a plan in 1984, known as the MacBride Principles The MacBride Principles — consisting of nine fair employment principles — are a corporate code of conduct for United States companies doing business in Northern Ireland and have become the Congressional standard for all US aid to, or for econ ...

, which he argued would eliminate discrimination against Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

by employers in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

and received widespread support for it in the United States and from Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gr ...

. However the MacBride Principles were criticised by the Irish and British governments and most political parties in Northern Ireland, including the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), as unworkable and counterproductive.

He was also a keen pan-Celticist.

Later life and death

In his later years, MacBride lived in his mother's home, Roebuck House, that served as a meeting place for many years for Irish nationalists, as well as in the Parisianarrondissement

An arrondissement (, , ) is any of various administrative divisions of France, Belgium, Haiti, certain other Francophone countries, as well as the Netherlands.

Europe

France

The 101 French departments are divided into 342 ''arrondissements ...

where he grew up with his mother, and enjoyed strolling along boyhood paths. While strolling through the Centre Pompidou Museum in 1979, and happening upon an exhibit for Amnesty International, he whispered to a colleague "Amnesty, you know, was one of my children."

In 1978, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.

Seán MacBride died in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

on 15 January 1988, eleven days before his 84th birthday. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in a grave with his mother, and his wife, who died in 1976.

On the occasion of MacBride's death the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

(ANC), Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and revolutionary who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography

Higher education

Oliv ...

stated "Seán MacBride will always be remembered for the concrete leadership he provided to the liberation movement and people of Namibia and South Africa. Driven by his own personal and political insight arising out of the cause of national freedom in Ireland ... our debt to him can never be repaid."

Legacy

Streets inWindhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 202 ...

, Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

and Amsterdam are named after him. The Headquarters of Amnesty International Ireland is called 'Seán MacBride House' in his honour. and the International Peace Bureau likewise named the 'Seán MacBride Prize' in his name.

A bust of MacBride was unveiled in Iveagh House, headquarters of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs in 1995.

In popular culture

A novel, ''The Casting of Mr O'Shaughnessy'', was published in 1995 (revised edition 2002) by Éamon Delaney in which the eponymous Mr O'Shaughnessy was, in the author's own words "partly, but quite obviously, based on the career of the colourful Seán MacBride".Career summary

*1946–1965 Leader of Clann na Poblachta *1947–1958 Member ofDáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland rea ...

*1948–1951 Minister for External Affairs of Ireland in Inter-Party Government

*1948–1951 Vice-president of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC)

*1950 President, Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe

*1954 Offered but declined, Ministerial office in Irish Government

*1963–1971 Secretary-General, International Commission of Jurists

*1966 Consultant to the Pontifical Commission on Justice and Peace

*1961–1975 chairman Amnesty International Executive

*1968–1974 Chairman of the Executive International Peace Bureau

*1975–1985 President of the Executive International Peace Bureau

*1968–1974 Chairman Special Committee of International NGOs on Human Rights (Geneva)

*1973 Vice-chairman, Congress of World Peace Forces (Moscow, October 1973)

*1973 Vice-president, World Federation of United Nations Associations

*1973–1977 Elected by the General Assembly of the United Nations to the post of United Nations Commissioner for Namibia with rank of Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations

*1977–1980 Chairman, Commission on International Communication for UNESCO

*1982 Chairman of the International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon

Further reading

* * Jordan, Anthony J, (1993), ''Seán A biography of Seán MacBride'', Blackwater PressReferences

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Macbride, Sean 1904 births 1988 deaths Alumni of University College Dublin Amnesty International people Anti-apartheid activists Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery Clann na Poblachta TDs Interwar-period spies Irish barristers Irish diplomats Irish expatriates in France Irish Nobel laureates Irish officials of the United Nations Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Irish Republican Army (1922–1969) members Irish spies for the Soviet Union Lenin Peace Prize recipients Ministers for Foreign Affairs (Ireland)Sean

Sean, also spelled Seán or Séan in Irish English, is a male given name of Irish origin. It comes from the Irish versions of the Biblical Hebrew name ''Yohanan'' (), Seán ( anglicized as '' Shaun/Shawn/ Shon'') and Séan ( Ulster variant; a ...

Members of the 12th Dáil

Members of the 13th Dáil

Members of the 14th Dáil

Members of the 15th Dáil

Nobel Peace Prize laureates

People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side)

Soviet spies against Western Europe

People educated at Downside School