Scottish religion in the nineteenth century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scottish religion in the nineteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the 19th century. This period saw a reaction to the population growth and urbanisation of the Industrial Revolution that had undermined traditional parochial structures and religious loyalties. The established Church of Scotland reacted with a programme of church building from the 1820s. Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the established Church of Scotland led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the

Scottish religion in the nineteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the 19th century. This period saw a reaction to the population growth and urbanisation of the Industrial Revolution that had undermined traditional parochial structures and religious loyalties. The established Church of Scotland reacted with a programme of church building from the 1820s. Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the established Church of Scotland led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by Thomas Chalmers, by the early 1840s it had added 222 churches, largely through public subscription.C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 17–18. The Church was increasingly divided between the

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by Thomas Chalmers, by the early 1840s it had added 222 churches, largely through public subscription.C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 17–18. The Church was increasingly divided between the

After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the

After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the  In 1860 there was a well publicized matter of charges against Reverend John MacMillan of Cardross which he refuted and numerously appealed which became known as

In 1860 there was a well publicized matter of charges against Reverend John MacMillan of Cardross which he refuted and numerously appealed which became known as

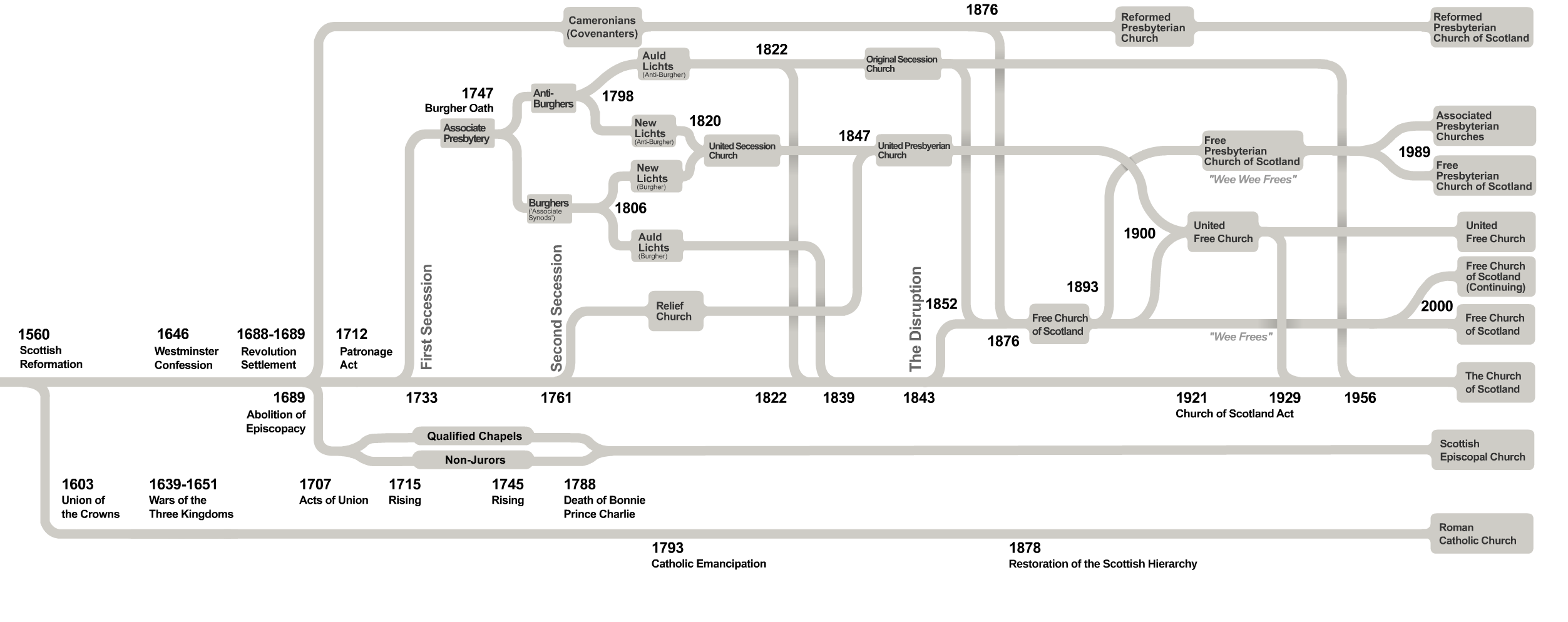

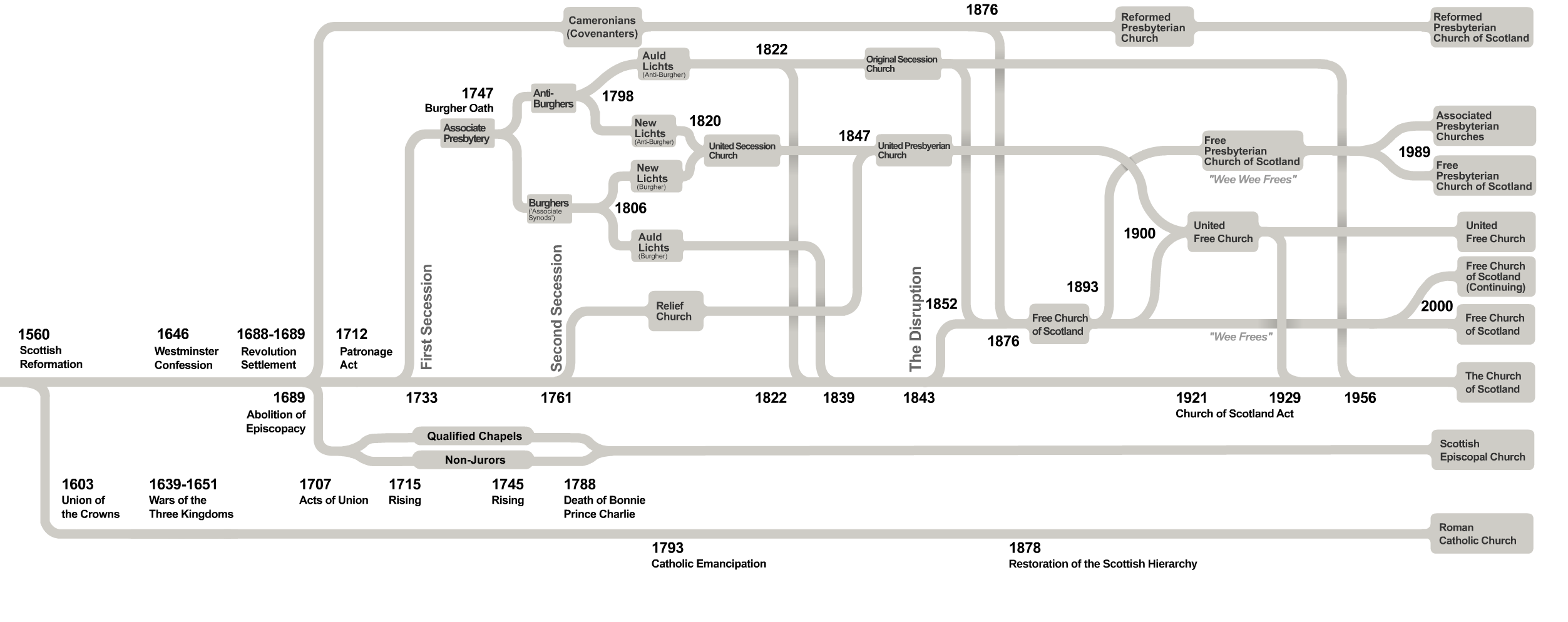

In the eighteenth century divisions within the Church of Scotland had led to the creation of the Associate Presbytery and Presbytery of Relief. The Associate Presbytery then split over the Burgess oath imposed after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, with one faction forming the separate General Associate Synod.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 293. Between 1799 and 1806 the

In the eighteenth century divisions within the Church of Scotland had led to the creation of the Associate Presbytery and Presbytery of Relief. The Associate Presbytery then split over the Burgess oath imposed after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, with one faction forming the separate General Associate Synod.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 293. Between 1799 and 1806 the

After the Reformation, Catholicism had survived as a mission, largely confined to the Highlands and Islands, but in the late eighteenth century declined in numbers due to extensive emigration from the region. In 1827 the mission was remodelled into Western, Eastern and Northern districts. Blairs College was established as a seminary in 1829.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 366-7. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation in the fortunes of Catholicism. The Church was initially unable to keep pace with the growth. By 1840 Glasgow had a Catholic population of 40,000, but only two churches and four priests to service them. A programme of church building and expansion of the priesthood began to catch up with the growth and by 1859 seven new churches had been built in the city.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 404. In 1878, despite opposition, a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy was restored to the country, and Catholicism became a significant denomination within Scotland.

After the Reformation, Catholicism had survived as a mission, largely confined to the Highlands and Islands, but in the late eighteenth century declined in numbers due to extensive emigration from the region. In 1827 the mission was remodelled into Western, Eastern and Northern districts. Blairs College was established as a seminary in 1829.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 366-7. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation in the fortunes of Catholicism. The Church was initially unable to keep pace with the growth. By 1840 Glasgow had a Catholic population of 40,000, but only two churches and four priests to service them. A programme of church building and expansion of the priesthood began to catch up with the growth and by 1859 seven new churches had been built in the city.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 404. In 1878, despite opposition, a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy was restored to the country, and Catholicism became a significant denomination within Scotland.

The first known Jews in Scotland were teachers of Hebrew at the universities in the seventeenth century. These were followed by merchants and tradesmen, mainly from Germany. The first Jewish congregation was founded in Edinburgh in 1816, and that in Glasgow in 1823. Scotland's first synagogue was set up in Edinburgh in 1825. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was an influx of Jewish refugees, most from eastern Europe and escaping poverty and persecution. Many were skilled in the tailoring, furniture and fur trades and congregated in the working class districts of Lowland urban centres, like the Gorbals in Glasgow. The largest community in Glasgow may have been 1,000 strong in 1879 and had perhaps reached 5,000 by the end of the century. A synagogue was built at Garnethill in 1879.W. Moffat, ''A History of Scotland: Modern Times'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), , p. 38. Over 8,000 Jews were resident in Scotland in 1903.

The first known Jews in Scotland were teachers of Hebrew at the universities in the seventeenth century. These were followed by merchants and tradesmen, mainly from Germany. The first Jewish congregation was founded in Edinburgh in 1816, and that in Glasgow in 1823. Scotland's first synagogue was set up in Edinburgh in 1825. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was an influx of Jewish refugees, most from eastern Europe and escaping poverty and persecution. Many were skilled in the tailoring, furniture and fur trades and congregated in the working class districts of Lowland urban centres, like the Gorbals in Glasgow. The largest community in Glasgow may have been 1,000 strong in 1879 and had perhaps reached 5,000 by the end of the century. A synagogue was built at Garnethill in 1879.W. Moffat, ''A History of Scotland: Modern Times'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), , p. 38. Over 8,000 Jews were resident in Scotland in 1903.

There was a liturgical revival in the late nineteenth century that affected most of the major denominations. This was strongly influenced by the English

There was a liturgical revival in the late nineteenth century that affected most of the major denominations. This was strongly influenced by the English

Scottish religion in the nineteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the 19th century. This period saw a reaction to the population growth and urbanisation of the Industrial Revolution that had undermined traditional parochial structures and religious loyalties. The established Church of Scotland reacted with a programme of church building from the 1820s. Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the established Church of Scotland led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the

Scottish religion in the nineteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the 19th century. This period saw a reaction to the population growth and urbanisation of the Industrial Revolution that had undermined traditional parochial structures and religious loyalties. The established Church of Scotland reacted with a programme of church building from the 1820s. Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the established Church of Scotland led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the Great Disruption

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland Free Church of Scotland may refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), seceded in 1843 from the Church of Scotland. The majority merged in 1900 into the United Free Church of Scotland; historical

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), rema ...

. The evangelical Free Church and other secessionist churches grew rapidly in the Highlands and Islands and urban centres. There were further schisms and divisions, particularly between those who attempted to maintain the principles of Calvinism and those that took a more personal and flexible view of salvation. However, there were also mergers that cumulated in the creation of a United Free Church

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

in 1900 that incorporated most of the secessionist churches.

Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants led to an expansion of Catholicism, with the restoration of the Church hierarchy in 1878. Episcopalianism also revived in the nineteenth century with the Episcopal Church in Scotland being organised as an autonomous body in communion with the Church of England in 1804. Other voluntary denominations included Baptists, Congregationalists and Methodists, which had entered the country in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, expanded in the nineteenth century and played a major part in religious and educational life, while the established church lost its monopoly over schooling and poor relief. The attempt to deal with the social problems of the growing working classes led to the rapid expansion of temperance societies

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting Temperance (virtue), temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, a ...

and other religious organisations such as the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

and Freemasonry. There were also missions at home to the Highlands and Islands and expanding urban centres and abroad, particularly to Africa, following the example of David Livingstone, who became a national icon.

Church of Scotland

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by Thomas Chalmers, by the early 1840s it had added 222 churches, largely through public subscription.C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 17–18. The Church was increasingly divided between the

The rapid population expansion in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly in the major urban centres, overtook the system of parishes on which the established church depended, leaving large numbers of "unchurched" workers, who were estranged from organised religion. The Kirk began to concern itself with providing churches in the new towns and relatively thinly supplied Highlands, establishing a church extension committee in 1828. Chaired by Thomas Chalmers, by the early 1840s it had added 222 churches, largely through public subscription.C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 17–18. The Church was increasingly divided between the Evangelicals

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

and the Moderate Party. While Evangelicals emphasised the authority of the Bible and the traditions and historical documents of the kirk, the Moderates, who had dominated the General Assembly of the Church since the mid-eighteenth century, tended to stress intellectualism in theology, the established hierarchy of the kirk and attempted to raise the social status of the clergy. The major issue was the patronage of landholders and heritors over appointments to the ministry. Chalmers began as a Moderate, but increasingly became an Evangelical, emerging as the leading figure in the movement.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 303-4.

Great Disruption

After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the

After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

and passed the Veto Act, which allowed congregations to reject unwanted "intrusive" presentations to livings by patrons and the Chapels Act, which put the ministers of Chapels of Ease

A chapel of ease (or chapel-of-ease) is a church building other than the parish church, built within the bounds of a parish for the attendance of those who cannot reach the parish church conveniently.

Often a chapel of ease is deliberately bu ...

on an equal footing with ordinary parish ministers. The following "Ten Years' Conflict" of legal and political wrangling ended in defeat for the non-intrusionists in the civil courts, reaching the Court of Session

The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland and constitutes part of the College of Justice; the supreme criminal court of Scotland is the High Court of Justiciary. The Court of Session sits in Parliament House in Edinburgh ...

and then finally the House of Lords in 1839, which declared the acts unconstitutional. In 1842 Evangelicals presented to the General Assembly a ''Claim, Declaration and Protest anent the Encroachments of the Court of Session'', known as the Claim of Right, that questioned the validity of civil jurisdiction over the church. When the Claim of Right was rejected by the General Assembly the result was a schism from the church by some of the non-intrusionists led by Thomas Chalmers, known as the Great Disruption of 1843.

Some 454, roughly a third, of the 1,195 clergy of the established church, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland Free Church of Scotland may refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), seceded in 1843 from the Church of Scotland. The majority merged in 1900 into the United Free Church of Scotland; historical

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), rema ...

. The Free Church was more accepting of Gaelic language and culture, grew rapidly in the Highlands and Islands, appealing much more strongly than did the established church,G. Robb, "Popular Religion and the Christianisation of the Scottish Highlands in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries", ''Journal of Religious History'', 1990, 16(1), pp. 18-34. and where the groundwork had been laid by the Evangelical Revival that had begun in the eighteenth century and had entered a second wave, known as the Second Great Awakening, with events like the Kilsyth

Kilsyth (; Scottish Gaelic ''Cill Saidhe'') is a town and civil parish in North Lanarkshire, roughly halfway between Glasgow and Stirling in Scotland. The estimated population is 9,860. The town is famous for the Battle of Kilsyth and the relig ...

Revival in 1839.

Until the Disruption the Church of Scotland had been seen as the religious expression of national identity and the guardian of Scotland's morals. It had considerable control over moral discipline, schools and the poor law system, but after 1843 it was a minority church, with reduced moral authority and control of the poor and education.S. J. Brown, "The Disruption" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 170-2. The established church took time to recover, but embarked on a programme of church building to rival the Free Church, increasing its number of parishes from 924 in 1843 to 1,437 by 1909.

In 1860 there was a well publicized matter of charges against Reverend John MacMillan of Cardross which he refuted and numerously appealed which became known as

In 1860 there was a well publicized matter of charges against Reverend John MacMillan of Cardross which he refuted and numerously appealed which became known as the Cardross Case

The Cardross Case was a 19th-century court case in Cardross in Scotland involving the Parish of Cardross and The Free Church of Scotland. It tested the limits between ecclesiastical and secular courts. The 19th century was an eventful period f ...

.

Free Church

At the Disruption the established Church kept all the properties, buildings and endowments and Free Church ministers led services in the open air, barns, boats and one disused public house, sometimes having temporary use of existing dissenting meeting houses.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 401. However, with Chalmer's skills in financial organisation they created a voluntary fund of over £400,000 to build 700 new churches by his death in 1847 and 400manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from '' ...

s soon followed. An equal or larger amount was expended on the building of 500 parochial schools, and New College in Edinburgh for training clergy. After the passing of the Education Act of 1872, most of these schools were voluntarily transferred to the newly established public school-boards.J. Brown Stewart, ''Thomas Chalmers and the Godly Commonwealth in Scotland'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), .T. M. Devine, ''The Scottish Nation, 1700-2000'' (London: Penguin Books, 2001), , pp. 91-100.

Chalmers's ideas shaped the breakaway group. He stressed a social vision that revived and preserved Scotland's communal traditions at a time of strain on the social fabric of the country. Chalmers's idealized small egalitarian, kirk-based, self-contained communities that recognized the individuality of their members and the need for cooperation. That vision also affected the mainstream Presbyterian churches, and by the 1870s it had been assimilated by the established Church of Scotland. Chalmers's ideals demonstrated that the church was concerned with the problems of urban society, and they represented a real attempt to overcome the social fragmentation that took place in industrial towns and cities.

In the late nineteenth century, the major debates were between fundamentalist Calvinists and theological liberals, who rejected a literal interpretation of the Bible.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1-5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416-7. This resulted in a further split in the Free Church, sometimes called the Second Disruption, as the rigid Calvinists broke away to form the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893.

Secession churches

In the eighteenth century divisions within the Church of Scotland had led to the creation of the Associate Presbytery and Presbytery of Relief. The Associate Presbytery then split over the Burgess oath imposed after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, with one faction forming the separate General Associate Synod.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 293. Between 1799 and 1806 the

In the eighteenth century divisions within the Church of Scotland had led to the creation of the Associate Presbytery and Presbytery of Relief. The Associate Presbytery then split over the Burgess oath imposed after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, with one faction forming the separate General Associate Synod.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 293. Between 1799 and 1806 the Old and New Light

The terms Old Lights and New Lights (among others) are used in Protestant Christian circles to distinguish between two groups who were initially the same, but have come to a disagreement. These terms originated in the early 18th century from a spl ...

controversy, with the "Old Lichts" following closely the principles of the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

s, while the "New Lichts" were more focused on personal salvation,M. Lynch, ''Scotland: a New History'' (London: Random House, 1991), , p. 400. split both the Associate and General Associate Presbyteries. This paved the way for a form of reunification, as both the New Licht factions joined in 1820 to form the United Secession Church

The United Secession Church (or properly the United Associate Synod of the Secession Church) was a Scottish Presbyterian denomination.

The First Secession from the established Church of Scotland had been in 1732, and the resultant "Associate Pre ...

, which claimed to have 361 congregations and 261,000 followers at its inception. The secession churches had made headway in recruitment, and by 1830 30 percent of the Scottish population were members. They made particular advances in the major urban centres. In Glasgow in 1835-36 40 per cent of the population were members and in Edinburgh and it was 42 per cent.

Reunions

In 1847 the United Secession Church was joined by the Presbytery of Relief to form the United Presbyterian Church. According to the religious census of 1851 it had 518 congregations and one in five of all churchgoers in Scotland. The Reformed Presbyterian Church had been established in 1743 from the remainingCameronian

Cameronian was a name given to a radical faction of Scottish Covenanters who followed the teachings of Richard Cameron, and who were composed principally of those who signed the Sanquhar Declaration in 1680. They were also known as Society Me ...

congregations, which had refused to accept the Restoration of Episcopalianism in 1660 and had not re-entered the Church of Scotland when it was established on a Presbyterian basis in 1690. All but a remnant joined the Free Church in 1876.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 298-9. The Free Church of Scotland and the United Presbyterian Church united in 1900 to form the United Free Church

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

. A small section of the Free Church, largely confined to the Highlands, rejected the union and continued independently under the name of the Free Church

A free church is a Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church does not define government policy, and a free church does not accept church theology or policy definitions from ...

.

Catholicism

After the Reformation, Catholicism had survived as a mission, largely confined to the Highlands and Islands, but in the late eighteenth century declined in numbers due to extensive emigration from the region. In 1827 the mission was remodelled into Western, Eastern and Northern districts. Blairs College was established as a seminary in 1829.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 366-7. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation in the fortunes of Catholicism. The Church was initially unable to keep pace with the growth. By 1840 Glasgow had a Catholic population of 40,000, but only two churches and four priests to service them. A programme of church building and expansion of the priesthood began to catch up with the growth and by 1859 seven new churches had been built in the city.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 404. In 1878, despite opposition, a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy was restored to the country, and Catholicism became a significant denomination within Scotland.

After the Reformation, Catholicism had survived as a mission, largely confined to the Highlands and Islands, but in the late eighteenth century declined in numbers due to extensive emigration from the region. In 1827 the mission was remodelled into Western, Eastern and Northern districts. Blairs College was established as a seminary in 1829.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 366-7. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation in the fortunes of Catholicism. The Church was initially unable to keep pace with the growth. By 1840 Glasgow had a Catholic population of 40,000, but only two churches and four priests to service them. A programme of church building and expansion of the priesthood began to catch up with the growth and by 1859 seven new churches had been built in the city.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 404. In 1878, despite opposition, a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy was restored to the country, and Catholicism became a significant denomination within Scotland.

Episcopalianism

The Episcopal Church had its origins in the congregations, ministers and bishops that did not accept the Presbyterian settlement after the Glorious Revolution in 1690 and among theQualified Chapel

A Qualified Chapel, in eighteenth and nineteenth century Scotland, was an Episcopal congregation that worshipped liturgically but accepted the Hanoverian monarchy and thereby "qualified" under the Scottish Episcopalians Act 1711 for exemption fr ...

s of English and Scottish congregations that grew around Anglican worship in the eighteenth century. Having suffered a decline in fortunes as a result of its associations with Jacobitism in the eighteenth century it revived in the nineteenth century as the issue of succession to the throne receded, becoming established as the Episcopal Church in Scotland in 1804, as an autonomous organisation in communion with the Church of England. A strand of Evangelicalism developed in the church in the early nineteenth century, but in 1843, the same year as the Great Disruption, a group in Edinburgh under its leading figure David Drummond broke away to form a separate English Episcopal congregation, and the Evangelical party within the church never recovered. The church undertook a programme of rapid church building in the late nineteenth century, culminating in the consecration of St Mary's Edinburgh, which eventually became a Cathedral.D. M. Murray, "Presbyterian Churches and denominations post-1690" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 83-5.

Voluntary churches

In the nineteenth century the fragmentation of the established church and the Evangelical Revival meant that the country began to gain relatively large numbers of non-conformist organisations, many from England and the US, known in Scotland as voluntary churches, since they stood outside the established system and participation and any payments were voluntary. The Quakers had established themselves in Scotland in the seventeenth century and Baptist, Congregationalist and Methodist churches had appeared in the eighteenth century, but did not begin significant growth until the nineteenth century, partly because more radical and evangelical traditions already existed within the Church of Scotland and the free churches.G. M. Ditchfield, ''The Evangelical Revival'' (London: Routledge, 1998), , p. 91. The Congregationalists organised themselves into a union in 1812, the Baptists, who were divided into Calvinists and non-Calvinist tendencies, did the same in 1869. The Methodist Church had probably been limited by its anti-Calvinist theology, but made advances in the century, particularly in Shetland.D. W. Bebbington, "Protestant sects and disestablishment" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 494-5. From 1879, they were joined by the evangelical revivalism of theSalvation Army

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

, which attempted to make major inroads in the growing urban centres. The Open and Exclusive Brethren entered Scotland in the late nineteenth century and the Open Brethren had 116 meetings in Scotland by 1884.C. G. Brown, ''Religion and Society in Scotland Since 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997) , p. 38.

Judaism

The first known Jews in Scotland were teachers of Hebrew at the universities in the seventeenth century. These were followed by merchants and tradesmen, mainly from Germany. The first Jewish congregation was founded in Edinburgh in 1816, and that in Glasgow in 1823. Scotland's first synagogue was set up in Edinburgh in 1825. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was an influx of Jewish refugees, most from eastern Europe and escaping poverty and persecution. Many were skilled in the tailoring, furniture and fur trades and congregated in the working class districts of Lowland urban centres, like the Gorbals in Glasgow. The largest community in Glasgow may have been 1,000 strong in 1879 and had perhaps reached 5,000 by the end of the century. A synagogue was built at Garnethill in 1879.W. Moffat, ''A History of Scotland: Modern Times'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), , p. 38. Over 8,000 Jews were resident in Scotland in 1903.

The first known Jews in Scotland were teachers of Hebrew at the universities in the seventeenth century. These were followed by merchants and tradesmen, mainly from Germany. The first Jewish congregation was founded in Edinburgh in 1816, and that in Glasgow in 1823. Scotland's first synagogue was set up in Edinburgh in 1825. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was an influx of Jewish refugees, most from eastern Europe and escaping poverty and persecution. Many were skilled in the tailoring, furniture and fur trades and congregated in the working class districts of Lowland urban centres, like the Gorbals in Glasgow. The largest community in Glasgow may have been 1,000 strong in 1879 and had perhaps reached 5,000 by the end of the century. A synagogue was built at Garnethill in 1879.W. Moffat, ''A History of Scotland: Modern Times'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), , p. 38. Over 8,000 Jews were resident in Scotland in 1903.

Liturgical and musical revival

There was a liturgical revival in the late nineteenth century that affected most of the major denominations. This was strongly influenced by the English

There was a liturgical revival in the late nineteenth century that affected most of the major denominations. This was strongly influenced by the English Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

, which encouraged a return to Medieval forms of architecture and worship, including the reintroduction of accompanied music into the Church of Scotland.B. D. Spinks, ''A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons'' (Scarecrow Press, 2009), , p. 149. The revival saw greater emphasis on the liturgical year and sermons tended to become shorter.D. M. Murray, "Sermons", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 581-2. The Church of Scotland was among the first European Protestant churches to engage in liturgical innovation reflected in seating arrangements, abandoning box pews for open benches. From the middle of the century some of its churches, like Greyfriars in Edinburgh, began installing organs and stained glass windows, reflecting an attempt to return to forms of worship largely excluded since the late seventeenth century. The Church Service Society

The Scottish Church Society is a Church of Scotland society founded in 1892. Leading founders were Thomas Leishman and William Milligan, and the first secretary was James Cooper.

Background

Although always a minority within the Church of Scotla ...

was founded in 1865 to promote liturgical study and reform. A year later organs were officially admitted to Church of Scotland churches. They began to be added to churches in large numbers and by the end of the century roughly a third of Church of Scotland ministers were members of the society and over 80 per cent of kirks had both organs and choirs. However, they remained controversial, with considerable opposition among conservative elements within the church and organs were never placed in some churches. At Duns

Duns may refer to:

* Duns, Scottish Borders, a town in Berwickshire, Scotland

** Duns railway station

** Duns F.C., a football club

** Duns RFC, a rugby football club

** Battle of Duns, an engagement fought in 1372

* Duns Scotus ( 1265/66–1308) ...

the church was rebuilt (opened 1888) in a plan used in the Middle Ages, with a separate chancel, communion table at the far end, and the pulpit under the chancel arch. The influence of the ecclesiological movement

The Cambridge Camden Society, known from 1845 (when it moved to London) as the Ecclesiological Society,Histor ...

can be seen in churches built at Crathie

Crathie ( gd, Craichidh) is a village in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It stands on the north bank of the River Dee.

Abergeldie Castle is away. It was built around 1550 and had 19th century additions. It was garrisoned by General Hugh Mackay in 1 ...

(opened 1893), which had an apsidal

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

chancel raised above the level of the nave, a stone pulpit and a brass lectern, and St Cuthbert's, Edinburgh (rebuilt 1894), with a marble communion table in a chancel decorated with marble and mosaic.N. Yates, ''Liturgical Space: Christian Worship and Church Buildings in Western Europe 1500–2000 Liturgy, Worship & Society'' (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), , pp. 128–9.

In the Episcopalian Church the influence of the Oxford Movement and links with the Anglican Church led to the introduction of more traditional services and by 1900 surplice

A surplice (; Late Latin ''superpelliceum'', from ''super'', "over" and ''pellicia'', "fur garment") is a liturgical vestment of Western Christianity. The surplice is in the form of a tunic of white linen or cotton fabric, reaching to the kne ...

d choirs and musical services were the norm. The Free Church was more conservative over music, and organs were not permitted until 1883.S. J. Brown, "Beliefs and religions" in T. Griffiths and G. Morton, ''A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), , p. 122. Hymns were first introduced in the United Presbyterian Church in the 1850s. They became common in the Church of Scotland and Free Church in the 1870s. The Church of Scotland adopted a hymnal with 200 songs in 1870 and the Free Church followed suit in 1882. The visit of American Evangelists Ira D. Sankey

Ira David Sankey (August 28, 1840 – August 13, 1908) was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades o ...

(1840–1908), and Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 26, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Massa ...

(1837–99) to Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1874-75 helped popularise accompanied church music in Scotland. The Moody-Sankey hymn book remained a best seller into the twentieth century. Sankey made the harmonium so popular that working-class mission congregations pleaded for the introduction of accompanied music.

Popular religion

Census of religion 1851

The British government undertook a census of religion in Scotland in 1851, sending forms to ministers to report on attendance at all their services on Sunday, 30 March 1851. The final report included numerous estimates to fill in blank information. It showed the attendance of the Church of Scotland at 19.9 percent of the population; of the Free Church at 19.2 percent; the United Presbyterians at 11.7 percent; and of the others at 10.1 percent – or just over 60 percent in all.Disruptions

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843 all undermined the tradition of parish schools. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools. Originally begun in the 1780s by town councils, they were adopted by all religious denominations in the nineteenth century. By the 1830s and 1840s these had widened to include mission schools,ragged schools

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children ...

, Bible societies and improvement classes, open to members of all forms of Protestantism and particularly aimed at the growing urban working classes. By 1890 the Baptists had more Sunday schools than churches and were teaching over 10,000 children. The number would double by 1914.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 403. The problem of a rapidly growing industrial workforce meant that the Old Poor Law, based on parish relief administered by the church, had broken down in the major urban centres. Thomas Chambers, who advocated self-help as a solution, lobbied forcibly for the exclusion of the able bodied from relief and that payment remained voluntary, but in periods of economic downturn genuine suffering was widespread. After the Disruption in 1845 the control of relief was removed from the church and given to parochial boards, but the level of relief remained inadequate for the scale of the problem.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , pp. 392-3.

The beginnings of the temperance movement can be traced to 1828–29 in Maryhill and Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, when it was imported from America. By 1850 it had become a central theme in the missionary campaign to the working classes. A new wave of temperance societies included the United Order of Female Rechabites and the Independent Order of Good Templars, which arrived from the US in 1869 and within seven years had 1100 branches in Scotland. The Salvation Army also placed an emphasis on sobriety. The Catholic Church had its own temperance movement, founding Catholic Total Abstinence Society in 1839. They made common cause with the Protestant societies, holding joint processions. Other religious based organisations that expanded in this period included the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, which had 15,000 members in Glasgow by the 1890s. Freemasonry also made advances in the late nineteenth century, particularly among skilled artisans.

Home missions

A major emphasis of Evangelical Protestantism were organised missions. In the eighteenth century the focus had been the Highlands and Islands through the Royal Bounty provided by the government and the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SSPCK), which had 229 schools in the Highlands by 1795.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 364. Gaelic school societies were founded, beginning in Edinburgh in 1811, supporting travelling schools to the northern Highlands and western Isles. In 1797James Haldane

The Rev James Alexander Haldane aka Captain James Haldane (14 July 1768 – 8 February 1851) was a Scottish independent church leader following an earlier life as a sea captain.

Biography

The youngest son of Captain James Haldane of Airth ...

founded the non-denominational Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at Home, whose lay-preachers established independent churches across the Highlands. When Haldane and his brother Robert accepted the principle of adult baptism in 1808 most of them became Baptist chapels. The Congregational Union of Scotland

The Congregational Union of Scotland was a Protestant church in the Reformed tradition.

The union was established in 1812, by 53 churches in Scotland. Its aim was to conduct missions in Scotland, and to support the existing Congregational churche ...

was formed in 1812 to promote home missions. In 1827 the Baptists consolidated their efforts in the Baptist Home Missionary Society. In 1824 the government provided funds to build 32 churches and 41 manses in the Highlands. After the Disruption in 1843 most of the expansion was in new churches established by the Free Church.D. W. Bebbington, "Missions at home" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 422-3.

Missions to fishermen and seamen began with the Seamen's Friend Societies. In the cities much of the work was interdenominational. The first urban mission was founded by David Nasmith in Glasgow in 1826 and drew on all the Protestant churches. Chalmers' experiment in St. John's, Glasgow, published in ''The Christian and Civic Economy of Large Towns'' (1821–26), provided a model of urban mission based on lay visitation. It was widely adopted by the Free Church after the Disruption and would be taken up by the Church of Scotland under the leadership of A. H. Charteris in the 1870s. The visit of American Evangelists Sankey and Moody in 1874-75 revitalised the Evangelical mission, leading to the founding of the Glasgow United Evangelistic Association. The Tent Hall was opened in the city in 1876, which hosted poor relief and evangelical meetings, and the Bible Training Institute

Bible Training Institute, established in 1892, was a bible college which aimed to evangelise the working classes in Scotland. It was closed in 2018 due to financial deficit.

History

The foundation of the Bible Training Institute, originally lo ...

for training lay evangelists was founded in 1892. Charteris was instrumental in the foundation of the Women's Guild

The Women's Institute (WI) is a community-based organisation for women in the United Kingdom, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand. The movement was founded in Stoney Creek, Ontario, Canada, by Erland and Janet Lee with Adelaide Hoodless being th ...

in 1887, which underlined the role of women in the missions. They also acted as Biblewomen, reading scriptures, and in teaching Sunday schools.

Overseas missions

The Scottish churches were relatively late to take up the challenge of foreign missions. The most famous Scottish missionary, David Livingstone, was not funded from his home country, but by the London Missionary Society. After his "disappearance" and death in the 1870s he became an icon of evangelic outreach, self-improvement, exploration and a form of colonialism.A. C. Ross, ''David Livingstone: Mission and Empire'' (London: Continuum, 2006), , pp. 242-5. The legacy of Livingstone can be seen in the names of many mission stations founded following his example, such as Blantyre (the place of Livingstone's birth) for the Church of Scotland andLivingstonia

Livingstonia or Kondowe is a town located in the Northern Region district of Rumphi in Malawi. It is north of the capital, Lilongwe, and connected by road to Chitimba on the shore Lake Malawi.

History

Livingstonia was founded in 1894 by mis ...

for the Free Church, both now in Malawi. As well as the cult of Livingstone, Scottish missionary efforts were also fuelled by the rivalry between different denominations in Scotland, and may have helped distract from problems at home. The missions were popularised at home by publications and illustrations, often particularly designed to appeal to children, and through the new medium of the magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a sin ...

show, shown to audiences in church halls throughout the country.R. J. Finley, "Missions overseas" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 245-6.

Notes

{{Nineteenth-century Scotland 19th century in Scotland 19th century in religion History of Christianity in Scotland 19th-century Christianity