Scotland in the High Middle Ages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass

At the close of the ninth century, various polities occupied Scotland. The

At the close of the ninth century, various polities occupied Scotland. The

After Ragnall ua Ímair,

After Ragnall ua Ímair,

By the mid-tenth century Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns and the region gets the modern name of Galloway from the mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement that produced the Gall-Gaidel.

By the mid-tenth century Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns and the region gets the modern name of Galloway from the mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement that produced the Gall-Gaidel.

Domnall mac Causantín's nickname was ''dásachtach''. This simply meant a madman, or, in early Irish law, a man not in control of his functions and hence without legal culpability. The following long reign (900–942/3) of his successor Causantín is more often regarded as the key to the formation of the Kingdom of Alba.

The period between the accession of Máel Coluim I and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda was marked by good relations with the

Domnall mac Causantín's nickname was ''dásachtach''. This simply meant a madman, or, in early Irish law, a man not in control of his functions and hence without legal culpability. The following long reign (900–942/3) of his successor Causantín is more often regarded as the key to the formation of the Kingdom of Alba.

The period between the accession of Máel Coluim I and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda was marked by good relations with the  It was Máel Coluim III, not his father Donnchad, who did more to create the

It was Máel Coluim III, not his father Donnchad, who did more to create the

The period between the accession of

The period between the accession of  The first instance of strong opposition to the Scottish kings was perhaps the revolt of Óengus, the Mormaer of Moray. Other important resistors to the expansionary Scottish kings were Somerled,

The first instance of strong opposition to the Scottish kings was perhaps the revolt of Óengus, the Mormaer of Moray. Other important resistors to the expansionary Scottish kings were Somerled,

At the beginning of this period, the boundaries of Alba contained only a small proportion of modern Scotland. Even when these lands were added to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the term ''

At the beginning of this period, the boundaries of Alba contained only a small proportion of modern Scotland. Even when these lands were added to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the term ''

The Scottish economy of this period was dominated by agriculture and by short-distance, local trade. There was an increasing amount of foreign trade in the period, as well as exchange gained by means of military plunder. By the end of this period, coins were replacing barter goods, but for most of this period most exchange was done without the use of metal currency.

Most of Scotland's agricultural wealth in this period came from

The Scottish economy of this period was dominated by agriculture and by short-distance, local trade. There was an increasing amount of foreign trade in the period, as well as exchange gained by means of military plunder. By the end of this period, coins were replacing barter goods, but for most of this period most exchange was done without the use of metal currency.

Most of Scotland's agricultural wealth in this period came from

The office of Justiciar and Judex were just two ways that Scottish society was governed. In the earlier period, the king "delegated" power to hereditary native "officers" such as the Mormaers/Earls and Toísechs/Thanes. It was a

The office of Justiciar and Judex were just two ways that Scottish society was governed. In the earlier period, the king "delegated" power to hereditary native "officers" such as the Mormaers/Earls and Toísechs/Thanes. It was a

Shetlopedia. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

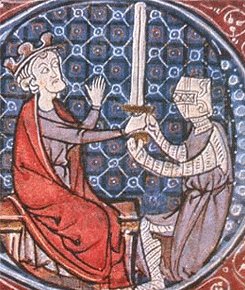

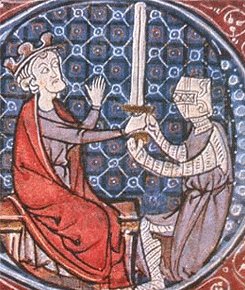

By the twelfth century the ability of lords and the king to call on wider bodies of men beyond their household troops for major campaigns had become the "common" (''communis exertcitus'') or "Scottish army" (''exercitus Scoticanus''), the result of a universal obligation based on the holding of variously named units of land. Later decrees indicated that the common army was a levy of all able-bodied freemen aged between 16 and 60, with 8-days warning.Brown (2004) p. 58. It produced relatively large numbers of men serving for a limited period, usually as unarmoured or poorly armoured bowmen and spearmen.Stringer (1993) pp. 30-31. In this period it continued to be mustered by the

By the twelfth century the ability of lords and the king to call on wider bodies of men beyond their household troops for major campaigns had become the "common" (''communis exertcitus'') or "Scottish army" (''exercitus Scoticanus''), the result of a universal obligation based on the holding of variously named units of land. Later decrees indicated that the common army was a levy of all able-bodied freemen aged between 16 and 60, with 8-days warning.Brown (2004) p. 58. It produced relatively large numbers of men serving for a limited period, usually as unarmoured or poorly armoured bowmen and spearmen.Stringer (1993) pp. 30-31. In this period it continued to be mustered by the

The Viking onslaught of the

The Viking onslaught of the

By the tenth century, all of northern Britain was Christianised, except the Scandinavian north and west, which had been lost to the church in the face of Norse settlement.

By the tenth century, all of northern Britain was Christianised, except the Scandinavian north and west, which had been lost to the church in the face of Norse settlement.

There is some evidence that Christianity made inroads into the Viking-controlled

There is some evidence that Christianity made inroads into the Viking-controlled  At the beginning of the period Scottish monasticism was dominated by

At the beginning of the period Scottish monasticism was dominated by

As a predominantly Gaelic society, most Scottish cultural practices throughout this period mirrored closely those of

As a predominantly Gaelic society, most Scottish cultural practices throughout this period mirrored closely those of  In the Middle Ages, Scotland was renowned for its musical skill.

In the Middle Ages, Scotland was renowned for its musical skill.

The Irish thought of Scotland as a provincial place. Others thought of it as an outlandish or barbaric place. "Who would deny that the Scots are barbarians?" was a rhetorical question posed in the 12th century by the Anglo-Flemish author of ''

The Irish thought of Scotland as a provincial place. Others thought of it as an outlandish or barbaric place. "Who would deny that the Scots are barbarians?" was a rhetorical question posed in the 12th century by the Anglo-Flemish author of ''

In this period, the word "Scot" was not the word used by the vast majority of Scots to describe themselves, except to foreigners, among whom it was the most common word. The Scots called themselves ''Albanach'' or simply ''Gaidel''. Both "Scot" and ''Gaidel'' were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. As the author of '' De Situ Albanie'' notes at the beginning of the thirteenth century: "The name Arregathel rgyllmeans margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'."

Likewise, the inhabitants of English and Norse-speaking parts were ethnically linked with other regions of Europe. At

In this period, the word "Scot" was not the word used by the vast majority of Scots to describe themselves, except to foreigners, among whom it was the most common word. The Scots called themselves ''Albanach'' or simply ''Gaidel''. Both "Scot" and ''Gaidel'' were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. As the author of '' De Situ Albanie'' notes at the beginning of the thirteenth century: "The name Arregathel rgyllmeans margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'."

Likewise, the inhabitants of English and Norse-speaking parts were ethnically linked with other regions of Europe. At

"Laws and Languages: Some Historical Notes from Scotland"

vol 6.2 ''Electronic Journal of Comparative Law'', (July 2002). * MacQuarrie, Alan, "Crusades", in M. Lynch (ed.) ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'', (New York, 2001), pp. 115–116. * MacQuarrie, Alan, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp, 2004). * Murdoch, S., ''The Terror of the Seas?: Scottish Maritime Warfare, 1513-1713'', Brill, (2010). * Murison, David D., "Linguistic Relations in Medieval Scotland", in G. W. S. Barrow (ed.), ''The Scottish Tradition: Essays in Honour of Ronald Gordon Cant'', (Edinburgh, 1974). * Neville, Cynthia J., ''Native Lordship in Medieval Scotland: The Earldoms of Strathearn and Lennox, c. 1140–1365'', (Portland/Dublin, 2005). * Nicolaisen, W. F. H., ''Scottish Place-Names'', (Edinburgh, 1976), 2nd ed. (2001). * Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998

''Vikings in Ireland and Scotland in the Ninth Century''

CELT. Retrieved 12 February 2012. * Oram, Richard D., "The Earls and Earldom of Mar, c. 1150–1300", Steve Boardman and Alasdair Ross (eds.) ''The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, c. 1200–1500'', (Dublin/Portland, 2003). pp. 46–66. * Oram, Richard, David: The King Who Made Scotland, (Gloucestershire, 2004). * Oram, Richard, ''The Lordship of Galloway'', (Edinburgh, 2000). * Owen, D. D. R., ''The Reign of William the Lion: Kingship and Culture, 1143–1214'', (East Linton, 1997). * Pittock, Murray G. H., ''Celtic Identity and the British Image'', (Manchester, 1999). * Potter, P. J., ''Gothic Kings of Britain: the Lives of 31 Medieval Rulers, 1016-1399'' (McFarland, 2008). * Price, Glanville, ''Languages in Britain and Ireland'', Blackwell (Oxford, 2000) . * Roberts, John L., ''Lost Kingdoms: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages'', (Edinburgh, 1997). *

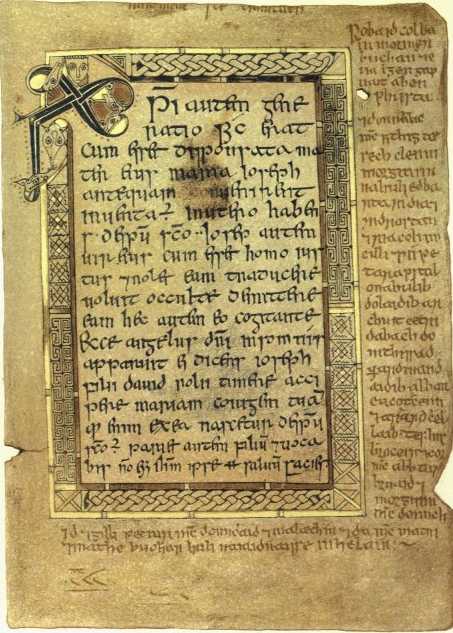

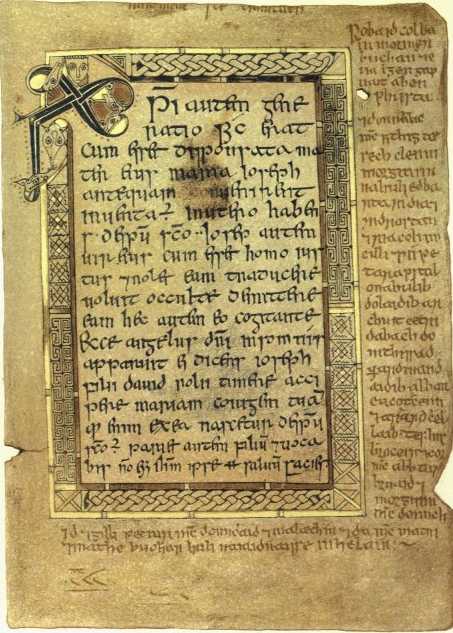

Annals of Tigernach

Gaelic Notes on the Book of Deer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scotland In The High Middle Ages History of Scotland by period

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of ...

.

At the close of the ninth century, various competing kingdoms occupied the territory of modern Scotland. Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

n influence was dominant in the northern and western islands, Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

culture in the southwest, the Anglo-Saxon or English Kingdom of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

in the southeast and the Pictish

Pictish is the extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographica ...

and Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba ( la, Scotia; sga, Alba) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the ...

in the east, north of the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of t ...

. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, northern Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

was increasingly dominated by Gaelic culture, and by the Gaelic regal lordship of ''Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kin ...

'', known in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

as either ''Albania'' or ''Scotia

Scotia is a Latin placename derived from ''Scoti'', a Latin name for the Gaels, first attested in the late 3rd century.Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 The Romans referred to Ireland as "Scotia" around ...

'', and in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

as "Scotland". From its base in the east, this kingdom acquired control of the lands lying to the south and ultimately the west and much of the north. It had a flourishing culture, comprising part of the larger Gaelic-speaking world and an economy dominated by agriculture and trade.

After the twelfth-century reign of King David I

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcol ...

, the Scottish monarchs

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

are better described as Scoto-Norman

The term Scoto-Norman (also Franco-Scottish or Franco-Gaelic) is used to describe people, families, institutions and archaeological artifacts that are partly Scottish people, Scottish (in some sense) and partly Anglo-Normans, Anglo-Norman (in some ...

than Gaelic, preferring French culture

The culture of France has been shaped by geography, by historical events, and by foreign and internal forces and groups. France, and in particular Paris, has played an important role as a center of high culture since the 17th century and from ...

to native Scottish culture. A consequence was the spread of French institutions and social values including Canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

. The first towns, called burghs

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

, appeared in the same era, and as they spread, so did the Middle English language

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

. These developments were offset by the acquisition of the Norse-Gaelic west and the Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaelic, or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread from Ire ...

of many of the noble families of French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Anglo-French

Anglo-French (or sometimes Franco-British) may refer to:

*France–United Kingdom relations

*Anglo-Norman language or its decendants, varieties of French used in medieval England

*Anglo-Français and Français (hound), an ancient type of hunting d ...

origin. National cohesion was fostered with the creation of various unique religious and cultural practices. By the end of the period, Scotland experienced a "Gaelic revival", which created an integrated Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions, of the Scottish people.

Although the various dialects of Gaelic, the Scots lan ...

. By 1286, these economic, institutional, cultural, religious and legal developments had brought Scotland closer to its neighbours in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and the Continent

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, although outsiders continued to view Scotland as a provincial, even savage place. By this date, the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

had political boundaries that closely resembled those of the modern nation.

Historiography

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in the High Middle Ages is a relatively well-studied topic and Scottish medievalists have produced a wide variety of publications. Some, such as David Dumville

David Norman Dumville (born 5 May 1949) is a British medievalist and Celtic scholar. He attended at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he studied Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic; Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München; and received his PhD a ...

, Thomas Owen Clancy

Thomas Owen Clancy is an American academic and historian who specializes in medieval Celtic literature, especially that of Scotland. He did his undergraduate work at New York University, and his Ph.D at the University of Edinburgh. He is currentl ...

and Dauvit Broun, are primarily interested in the native cultures of the country, and often have linguistic training in the Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

. Normanists, such as G.W.S. Barrow

Geoffrey Wallis Steuart Barrow (28 November 1924 – 14 December 2013) was a Scottish historian and academic.

The son of Charles Embleton Barrow and Marjorie née Stuart, Geoffrey Barrow was born on 28 November 1924, at Headingley near Leeds. ...

, are concerned with the Norman and Scoto-Norman

The term Scoto-Norman (also Franco-Scottish or Franco-Gaelic) is used to describe people, families, institutions and archaeological artifacts that are partly Scottish people, Scottish (in some sense) and partly Anglo-Normans, Anglo-Norman (in some ...

cultures introduced to Scotland after the eleventh century. For much of the twentieth century, historians tended to stress the cultural change that took place in Scotland during this time. However, scholars such as Cynthia Neville

Cynthia J Neville, FRHistS, FSAScot is a Canadian historian, medievalist and George Munro professor of history at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Neville's primary research interests are the social, political and cultural history ...

and Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, F.S.A. (Scot.) is a Scotland, Scottish historian. He is a professor of medieval and environmental history at the University of Stirling and an honorary lecturer in history at the Univer ...

, while not ignoring cultural changes, argue that continuity with the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

past was just as, if not more, important.

Since the publication of ''Scandinavian Scotland'' by Barbara E. Crawford in 1987, there has been a growing volume of work dedicated to the understanding of Norse influence in this period. However, from 849 on, when Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

's relics were removed from Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

in the face of Viking incursions, written evidence from local sources in the areas under Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

n influence all but vanishes for three hundred years. The sources for information about the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebri ...

and indeed much of northern Scotland from the eighth to the eleventh century, are thus almost exclusively Irish, English or Norse. The main Norse texts were written in the early thirteenth century and should be treated with care. The English and Irish sources are more contemporary, but according to historian Alex Woolf

Alex Woolf (born 12 July 1963) is a British medieval historian and academic. He specialises in the history of Britain and Ireland and to a lesser extent Scandinavia in the Early Middle Ages, with a particular emphasis on interaction and comp ...

, may have "led to a southern bias in the story", especially as much of the Hebridean archipelago became Norse-speaking during this period.

There are various traditional clan histories dating from the nineteenth century such as the "monumental" ''The Clan Donald'' and a significant corpus of material from the Gaelic oral tradition that relates to this period, although their value is questionable.

Origins of the Kingdom of Alba

At the close of the ninth century, various polities occupied Scotland. The

At the close of the ninth century, various polities occupied Scotland. The Pictish

Pictish is the extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographica ...

and Gaelic Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba ( la, Scotia; sga, Alba) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the ...

had just been united in the east; the Scandinavian-influenced Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or North ...

emerged in the west. Ragnall ua Ímair

Ragnall mac Bárid ua Ímair ( non, Rǫgnvaldr , died 921) or Rægnald was a Viking leader who ruled Northumbria and the Isle of Man in the early 10th century. He was a grandson of Ímar and a member of the Uí Ímair. Ragnall was most probably ...

was a key figure at this time although the extent to which he ruled territory in western and northern Scotland including the Hebrides and Northern Isles

The Northern Isles ( sco, Northren Isles; gd, Na h-Eileanan a Tuath; non, Norðreyjar; nrn, Nordøjar) are a pair of archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. They are part of Scotland, as are th ...

is unknown as contemporary sources are silent on this matter. Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; also sco, Dumbairton; ) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. In 2006, it had an estimated population of 19,990.

Dumbarton was the ca ...

, the capital of the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (lit. " Strath of the River Clyde", and Strað-Clota in Old English), was a Brittonic successor state of the Roman Empire and one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Britons, located in the region the Welsh tribes referred to as ...

had been sacked by the Uí Ímair

The Uí Ímair (; meaning ‘''scions of Ivar’''), also known as the Ivar Dynasty or Ivarids was a royal Norse-Gael dynasty which ruled much of the Irish Sea region, the Kingdom of Dublin, the western coast of Scotland, including the Hebrides ...

in 870.Woolf (2007) p. 109. This was clearly a major assault, which may have brought the whole of mainland Scotland under temporary Uí Imair control. The south-east had been absorbed by the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

Kingdom of Bernicia/Northumbria in the seventh century. Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

in the southwest was a Lordship with some regality. In a Galwegian Galwegian or Galwegians may refer to:

* Of Galway (disambiguation)

** Of or pertaining to Galway, Ireland, or to its residents.

** Galwegians RFC, rugby club in Galway, Ireland

* Of Galloway (disambiguation)

** Of, or pertaining to, Galloway, Scot ...

charter dated to the reign of Fergus, the Galwegian ruler styled himself ''rex Galwitensium'', King of Galloway. In the northeast the ruler of Moray was called not only "king" in both Scandinavian and Irish sources, but before Máel Snechtai, "King of Alba".

However, when Domnall mac Causantín died at Dunnottar in 900, he was the first man to be recorded as ''rí Alban'' and his kingdom was the nucleus that would expand as Viking and other influences waned. In the tenth century, the Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kin ...

n elite had begun to develop a conquest myth to explain their increasing Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaelic, or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread from Ire ...

at the expense of Pictish culture. Known as MacAlpin's Treason, it describes how Cináed mac Ailpín

Kenneth MacAlpin ( mga, Cináed mac Ailpin, label=Medieval Gaelic, gd, Coinneach mac Ailpein, label=Modern Scottish Gaelic; 810 – 13 February 858) or Kenneth I was King of Dál Riada (841–850), King of the Picts (843–858), and the Kin ...

is supposed to have annihilated the Picts in one fell takeover. However, modern historians are now beginning to reject this conceptualization of Scottish origins. No contemporary sources mention this conquest. Moreover, the Gaelicisation of Pictland was a long process predating Cináed, and is evidenced by Gaelic-speaking Pictish rulers, Pictish royal patronage of Gaelic poets, and Gaelic inscriptions and placenames. The change of identity can perhaps be explained by the death of the Pictish language

Pictish is the extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geograp ...

, but also important may be Causantín II's alleged Scoticisation of the "Pictish" Church and the trauma caused by Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasions, most strenuously felt in the Pictish kingdom's heartland of Fortriu

Fortriu ( la, Verturiones; sga, *Foirtrinn; ang, Wærteras; xpi, *Uerteru) was a Pictish kingdom that existed between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but ...

.

Scandinavian-influenced territories

Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles comprised the Hebrides, theislands of the Firth of Clyde

The Islands of the Firth of Clyde are the fifth largest of the major Scottish island groups after the Inner and Outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland. They are situated in the Firth of Clyde between Ayrshire and Argyll and Bute. There are about ...

and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the ''Suðreyjar'', or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the ''Norðreyjar'' or "Northern Isles

The Northern Isles ( sco, Northren Isles; gd, Na h-Eileanan a Tuath; non, Norðreyjar; nrn, Nordøjar) are a pair of archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. They are part of Scotland, as are th ...

" of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

and Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

, which were held by the Earls of Orkney

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally founded by Norse invaders, the status of the rulers of the N ...

as vassals of the Norwegian crown throughout the High Middle Ages.

Amlaíb Cuarán

Amlaíb mac Sitric (d. 980; non, Óláfr Sigtryggsson ), commonly called Amlaíb Cuarán (O.N.: ), was a 10th-century Norse-Gael who was King of Northumbria and Dublin. His byname, ''cuarán'', is usually translated as "sandal". His name ap ...

, who fought at the Battle of Brunanburh

The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the poin ...

in 937 and who also became King of Northumbria

Northumbria, a kingdom of Angles, in what is now northern England and south-east Scotland, was initially divided into two kingdoms: Bernicia and Deira. The two were first united by king Æthelfrith around the year 604, and except for occasional ...

, is the next King of the Isles on record.Gregory (1881) pp. 4–6. In the succeeding years Norse sources also list various rulers such as Gilli, Sigurd the Stout

Sigurd Hlodvirsson (23 April 1014), popularly known as Sigurd the Stout from the Old Norse ''Sigurðr digri'',Thomson (2008) p. 59 was an Earl of Orkney. The main sources for his life are the Norse Sagas, which were first written down some tw ...

, Håkon Eiriksson

Haakon Ericsson (Old Norse: ''Hákon Eiríksson''; no, Håkon Eiriksson; died c. 1029–1030) was the last Earl of Lade and governor of Norway from 1012 to 1015 and again from 1028 to 1029 as a vassal under Danish King Knut the Great.

Biograp ...

and Thorfinn Sigurdsson as rulers over the Hebrides as vassals of the Kings of Norway or Denmark.

Godred Crovan

Godred Crovan (died 1095), known in Gaelic as Gofraid Crobán, Gofraid Meránach, and Gofraid Méránach, was a Norse-Gaelic ruler of the kingdoms of Dublin and the Isles. Although his precise parentage has not completely been proven, he was c ...

became the ruler of Dublin and Mann from 1079''The Chronicle of Man and the Sudreys'' (1874) p. 51. and from the early years of the twelfth century the Crovan dynasty

The Crovan dynasty, from the late 11th century to the mid 13th century, was the ruling family of an insular kingdom known variously in secondary sources as the Kingdom of Mann, the Kingdom of the Isles, and the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles. The e ...

asserted themselves and ruled as "Kings of Mann and the Isles" for the next half-century. The kingdom was then sundered due to the actions of Somerled

Somerled (died 1164), known in Middle Irish as Somairle, Somhairle, and Somhairlidh, and in Old Norse as Sumarliði , was a mid-12th-century Norse-Gaelic lord who, through marital alliance and military conquest, rose in prominence to create the ...

whose sons inherited the southern Hebrides while the Manx rulers held on to the "north isles" for another century.

The North

The Scandinavian influence in Scotland was probably at its height in the mid eleventh century during the time of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, who attempted to create a single political and ecclesiastical domain stretching from Shetland to Man. The permanent Scandinavian holdings in Scotland at that time must therefore have been at least a quarter of the land area of modern Scotland. By the end of the eleventh century, the Norwegian crown had come to accept that Caithness was held by the Earls of Orkney as a fiefdom from the Kings of Scotland although its Norse character was retained throughout the thirteenth century.Raghnall mac Gofraidh

''Ragnall'', ''Raghnall'', ''Raonall'', and ''Raonull'' are masculine personal names or given names in several Gaelic languages.

''Ragnall'' occurs in Old Irish, and Middle Irish/ Middle Gaelic. It is a Gaelicised form of the Old Norse '' Røgnv ...

was granted Caithness after assisting the Scots king in a conflict with Harald Maddadson

Harald Maddadsson (Old Norse: ''Haraldr Maddaðarson'', Gaelic: ''Aralt mac Mataid'') (c. 1134 – 1206) was Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness from 1139 until 1206. He was the son of Matad, Mormaer of Atholl, and Margaret, daughter o ...

, an earl of Orkney in the early thirteenth century.

In the ninth century, Orcadian control stretched into Moray, which was a semi-independent kingdom for much of this early period. The Moray rulers Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

(1040–1057) and his successor Lulach (1057–1058) became rulers of the entire Scottish kingdom for a time.Mackie (1964) p. 43. However, Moray was subjugated by the Scottish kings after 1130, when the native ruler, Óengus of Moray

Óengus of Moray (''Oenghus mac inghine Lulaich, ri Moréb'') was the last king of Moray of the native line, ruling Moray in what is now northeastern Scotland from an unknown date until his death in 1130.

Óengus is known to have been the son of ...

was killed leading a rebellion. Another revolt in 1187 was equally unsuccessful.

South west Scotland

By the mid-tenth century Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns and the region gets the modern name of Galloway from the mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement that produced the Gall-Gaidel.

By the mid-tenth century Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns and the region gets the modern name of Galloway from the mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement that produced the Gall-Gaidel. Magnus Barelegs

Magnus Olafsson (Old Norse: ''Magnús Óláfsson'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Olavsson''; 1073 – 24 August 1103), better known as Magnus Barefoot (Old Norse: ''Magnús berfœttr'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Berrføtt''), was King of Norway (being Mag ...

is said to have "subdued the people of Galloway" in the eleventh century and Whithorn

Whithorn ( �ʍɪthorn 'HWIT-horn'; ''Taigh Mhàrtainn'' in Gaelic), is a royal burgh in the historic county of Wigtownshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christ ...

seems to have been a centre of Hiberno-Norse artisans who traded around the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the C ...

by the end of the first millennium.Graham-Campbell and Batey (1998) p. 203. However, the place name, written and archaeological evidence of extensive Norse (as opposed to Norse-Gael) settlement in the area is not convincing.Graham-Campbell and Batey (1998) pp. 106–108.

The ounceland system seems to have become widespread down the west coast including much of Argyll, and most of the southwest apart from a region near the inner Solway Firth

The Solway Firth ( gd, Tràchd Romhra) is a firth that forms part of the border between England and Scotland, between Cumbria (including the Solway Plain) and Dumfries and Galloway. It stretches from St Bees Head, just south of Whitehaven ...

. In Dumfries and Galloway

Dumfries and Galloway ( sco, Dumfries an Gallowa; gd, Dùn Phrìs is Gall-Ghaidhealaibh) is one of 32 unitary council areas of Scotland and is located in the western Southern Uplands. It covers the historic counties of Dumfriesshire, Kirkc ...

the place name evidence is complex and of mixed Gaelic, Norse and Danish influence, the last most likely stemming from contact with the extensive Danish holdings in northern England.Crawford (1987) pp. 87, 93, 98. Although the Scots obtained greater control after the death of Gilla Brigte and the accession of Lochlann

In the modern Gaelic languages, () signifies Scandinavia or, more specifically, Norway. As such it is cognate with the Welsh name for Scandinavia, (). In both old Gaelic and old Welsh, such names literally mean 'land of lakes' or 'land of s ...

in 1185, Galloway was not fully absorbed by Scotland until 1235, after the rebellion of the Galwegians was crushed.

Strathclyde

The main language of Strathclyde and elsewhere in the ''Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population sp ...

'' in the opening years of the High Middle Ages was Cumbric

Cumbric was a variety of the Common Brittonic language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the '' Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" in what is now the counties of Westmorland, Cumberland and northern Lancashire in Northern England and the south ...

, a variety of the British language akin to Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

. Sometime after 1018 and before 1054, the kingdom appears to have been conquered by the Scots, most probably during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda

Máel Coluim mac Cináeda ( gd, Maol Chaluim mac Choinnich, label=Modern Scottish Gaelic; anglicized Malcolm II; c. 954 – 25 November 1034) was King of Scots from 1005 until his death. He was a son of King Kenneth II; but the name of his mot ...

who died in 1034. At this time the territory of Strathclyde extended as far south as the River Derwent.Price (2000) p. 121. In 1054, the English king Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

dispatched Earl Siward of Northumbria

Siward ( or more recently ) or Sigurd ( ang, Sigeweard, non, Sigurðr digri) was an important earl of 11th-century northern England. The Old Norse nickname ''Digri'' and its Latin translation ''Grossus'' ("the stout") are given to him by near-c ...

against the Scots, then ruled by Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

. By the 1070s, if not earlier in the reign of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada

Malcolm III ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh; died 13 November 1093) was King of Scotland from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" ("ceann mòr", Gaelic, literally "big head" ...

, it appears that the Scots again controlled Strathclyde, although William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

annexed the southern portion in 1092. The territory was granted by Alexander I to his brother David, later King David I

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcol ...

, in 1107.

Kingdom of Alba or Scotia

Gaelic kings: Domnall II to Alexander I

Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity and, despite this, relatively successful expansionary policies. In 945, king Máel Coluim I received Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

as part of a deal with King Edmund of England, an event offset somewhat by Máel Coluim's loss of control in Moray. Sometime in the reign of king Idulb (954–962), the Scots captured the fortress called ''oppidum Eden'', i.e. Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. Scottish control of Lothian

Lothian (; sco, Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n; gd, Lodainn ) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Scott ...

was strengthened with Máel Coluim II's victory over the Northumbrians

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

at the Battle of Carham (1018). The Scots had probably some authority in Strathclyde since the later part of the ninth century, but the kingdom kept its own rulers, and it is not clear that the Scots were always strong enough to enforce their authority.

The reign of King Donnchad I from 1034 was marred by failed military adventures, and he was killed in a battle with the men of Moray, led by Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

who became king in 1040. Macbeth ruled for seventeen years, peaceful enough that he was able to leave to go on pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

; however, he was overthrown by Máel Coluim, the son of Donnchad, who some months later defeated Macbeth's stepson and successor Lulach to become king Máel Coluim III. In subsequent medieval propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

, Donnchad's reign was portrayed positively while Macbeth was vilified; William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

followed this distorted history with his portrayal of both the king and his queen consort, Gruoch

Gruoch ingen Boite () was a Scottish queen, the daughter of Boite mac Cináeda, son of Cináed II. She is most famous for being the wife and queen of MacBethad mac Findlaích (Macbeth). The dates of her life are uncertain.

Life

Gruoch is beli ...

, in his play ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

''.

It was Máel Coluim III, not his father Donnchad, who did more to create the

It was Máel Coluim III, not his father Donnchad, who did more to create the dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries. Part of the resource was the large number of children he had, perhaps as many as a dozen, through marriage to the widow or daughter of Thorfinn Sigurdsson and afterwards to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

, granddaughter of Edmund Ironside. However, despite having a royal Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

wife, Máel Coluim spent much of his reign conducting slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

raids against the English, adding to the woes of that people in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqu ...

and the Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North was a series of campaigns waged by William the Conqueror in the winter of 1069–1070 to subjugate northern England, where the presence of the last Wessex claimant, Edgar Ætheling, had encouraged Anglo- Danish re ...

. Marianus Scotus narrates that "the Gaels and French devastated the English; and he Englishwere dispersed and died of hunger; and were compelled to eat human flesh".

Máel Coluim's Queen Margaret was the sister of the native claimant to the English throne, Edgar Ætheling

Edgar Ætheling or Edgar II (c. 1052 – 1125 or after) was the last male member of the royal house of Cerdic of Wessex. He was elected King of England by the Witenagemot in 1066, but never crowned.

Family and early life

Edgar was born ...

. This marriage, and Máel Coluim's raids on northern England, prompted interference by the Norman rulers of England in the Scottish kingdom. King William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

invaded and Máel Coluim submitted to his authority, giving his oldest son Donnchad as a hostage. From 1079 onwards there were various cross-border raids by both parties and Máel Coluim himself and Edward, his eldest son by Margaret, died in one of them in the Battle of Alnwick, in 1093.

Tradition would have made his brother Domnall Bán

Donald III (Medieval Gaelic: Domnall mac Donnchada; Modern Gaelic: ''Dòmhnall mac Dhonnchaidh''), and nicknamed "Donald the Fair" or "Donald the White" (Medieval Gaelic:"Domnall Bán", anglicised as Donald Bane/Bain or Donalbane/Donalbain) (c. ...

Máel Coluim's successor, but it seems that Edward, his eldest son by Margaret, was his chosen heir. With Máel Coluim and Edward dead in the same battle, and his other sons in Scotland still young, Domnall was made king. However, Donnchad II, Máel Coluim's eldest son by his first wife, obtained some support from William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

and took the throne. According to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'' his English and French followers were massacred, and Donnchad II himself was killed later in the same year (1094) by Domnall's ally Máel Petair of Mearns

Máel Petair of Mearns is the only known Mormaer of the Mearns. His name means "tonsured one of (Saint) Peter".

Professor Dauvit Broun of the University of Glasgow identifies his father as a man called Loren. Little is known of him except that, ...

. In 1097, William Rufus sent another of Máel Coluim's sons, Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

, to take the kingship. The ensuing death of Domnall Bán secured the kingship for Edgar, and there followed a period of relative peace. The reigns of both Edgar and his successor Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

are obscure by comparison with their successors. The former's most notable act was to send a camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

(or perhaps an elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantida ...

) to his fellow Gael Muircheartach Ua Briain

Muircheartach Ua Briain (old spelling: Muirchertach Ua Briain) (also known as Murtaugh O'Brien) (c. 1050 – c. 10 March 1119), son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain and great-grandson of Brian Boru, was King of Munster and later self-declared High Ki ...

, High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardrí na hÉireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned an ...

. When Edgar died, Alexander took the kingship, while his youngest brother David became Prince of Cumbria.

Scoto-Norman kings: David I to Alexander III

The period between the accession of

The period between the accession of David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

and the death of Alexander III was marked by dependency upon and relatively good relations with the Kings of England. The period can be regarded as one of great historical transformation, part of a more general phenomenon, which has been called "Europeanisation". The period also witnessed the successful imposition of royal authority across most of the modern country. After David I, and especially in the reign of William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, Scotland's Kings became ambivalent about the culture of most of their subjects.William I was known as ''Uilleam Garbh'' (i.e. "William the Rough") in the contemporary Irish annals e.g. ''Annals of Ulster'', s.a. 1214.6; ''Annals of Loch Cé'', s.a. 1213.10. As Walter of Coventry

Walter of Coventry (fl. 1290), English monk and chronicler, who was apparently connected with a religious house in the province of York, is known to us only through the historical compilation which bears his name, the ''Memoriale fratris Walteri d ...

tells us, "The modern kings of Scotland count themselves as Frenchmen, in race, manners, language and culture; they keep only Frenchmen in their household and following, and have reduced the Gaels to utter servitude."

This situation was not without consequence. In the aftermath of William's capture at Alnwick

Alnwick ( ) is a market town in Northumberland, England, of which it is the traditional county town. The population at the 2011 Census was 8,116.

The town is on the south bank of the River Aln, south of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish bor ...

in 1174, the Scots turned on the small number of Middle English-speakers and French-speakers among them. William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury ( la, Guilelmus Neubrigensis, ''Wilhelmus Neubrigensis'', or ''Willelmus de Novoburgo''. 1136 – 1198), also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon of Anglo-Saxon de ...

related that the Scots first attacked the Scoto-English in their own army, and Newburgh reported a repetition of these events in Scotland itself. Walter Bower

Walter Bower (or Bowmaker; 24 December 1449) was a Scottish canon regular and abbot of Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth, who is noted as a chronicler of his era. He was born about 1385 at Haddington, East Lothian, in the Kingdom of Scot ...

, writing a few centuries later about the same events confirms that "there took place a most wretched and widespread persecution of the English both in Scotland and Galloway".

The first instance of strong opposition to the Scottish kings was perhaps the revolt of Óengus, the Mormaer of Moray. Other important resistors to the expansionary Scottish kings were Somerled,

The first instance of strong opposition to the Scottish kings was perhaps the revolt of Óengus, the Mormaer of Moray. Other important resistors to the expansionary Scottish kings were Somerled, Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway (died 12 May 1161) was a twelfth-century Lord of Galloway. Although his familial origins are unknown, it is possible that he was of Norse-Gaelic ancestry. Fergus first appears on record in 1136, when he witnessed a charter ...

, Gille Brigte, Lord of Galloway

Gille Brigte or Gilla Brigte mac Fergusa of Galloway (died 1185), also known as ''Gillebrigte'', ''Gille Brighde'', ''Gilbridge'', ''Gilbride'', etc., and most famously known in French sources as Gilbert, was Lord of Galloway of Scotland (from 11 ...

and Harald Maddadsson, along with two kin-groups known today as the MacHeths

__NOTOC__

The MacHeths were a Celtic kindred who raised several rebellions against the kings of Scotland in the 12th and 13th centuries. Their origins have long been debated.

Origins

The main controversy concerning the MacHeths is their origin. ...

and the MacWilliams. The threat from the latter was so grave that, after their defeat in 1230, the Scottish crown ordered the public execution of the infant girl who happened to be the last of the MacWilliam line. According to the ''Lanercost Chronicle'':

Many of these resistors collaborated, and drew support not just in the peripheral Gaelic regions of Galloway, Moray, Ross and Argyll, but also from eastern "Scotland-proper", and elsewhere in the Gaelic world. However, by the end of the twelfth century, the Scottish kings had acquired the authority and ability to draw in native Gaelic lords outside their previous zone of control in order to do their work, the most famous examples being Lochlann, Lord of Galloway

Lochlann of Galloway (died December 12, 1200), also known as Lochlan mac Uchtred and by his French name Roland fitz Uhtred, was the son and successor of Uchtred, Lord of Galloway as the "Lord" or "sub-king" of eastern Galloway.

Family

Lochlann w ...

and Ferchar mac in tSagairt. By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a strong position to annex the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson

Haakon IV Haakonsson ( – 16 December 1263; Old Norse: ''Hákon Hákonarson'' ; Norwegian: ''Håkon Håkonsson''), sometimes called Haakon the Old in contrast to his namesake son, was King of Norway from 1217 to 1263. His reign lasted for 46 y ...

's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. Through it, Scotland achieved the end of 500 years of Norse Viking depredations and invasions despite bei ...

with the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had becom ...

in 1266.Barrett (2008) p. 411. The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186 and the absorption of the Lordship of Galloway after the Galwegian revolt of Gille Ruadh

Gille Ruadh was the Galwegian leader who led the revolt against King Alexander II of Scotland. His birth, death date and origins are all unknown.

Upon Alan, Lord of Galloway's death in 1234, Galloway was left without a legitimate feudal heir. ...

in 1235 meant that Gaelic speakers under the rule of the Scottish king formed a majority of the population during the so-called Norman period. The integration of Gaelic, Norman and Saxon cultures that began to occur may have been the platform that enabled King Robert I Robert I may refer to:

*Robert I, Duke of Neustria (697–748)

* Robert I of France (866–923), King of France, 922–923, rebelled against Charles the Simple

* Rollo, Duke of Normandy (c. 846 – c. 930; reigned 911–927)

* Robert I Archbishop o ...

to emerge victorious during the Wars of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against for ...

, which followed soon after the death of Alexander III.

Geography

At the beginning of this period, the boundaries of Alba contained only a small proportion of modern Scotland. Even when these lands were added to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the term ''

At the beginning of this period, the boundaries of Alba contained only a small proportion of modern Scotland. Even when these lands were added to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the term ''Scotia

Scotia is a Latin placename derived from ''Scoti'', a Latin name for the Gaels, first attested in the late 3rd century.Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 The Romans referred to Ireland as "Scotia" around ...

'' was applied in sources only to the region between the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of t ...

, the central Grampians and the River Spey

The River Spey (Scottish Gaelic: Uisge Spè) is a river in the northeast of Scotland. At it is the eighth longest river in the United Kingdom, as well as the second longest and fastest-flowing river in Scotland. It is important for salmon fishi ...

and only began to be used to describe all of the lands under the authority of the Scottish crown from the second half of the twelfth century. By the late thirteenth century when the Treaty of York (1237) and Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had becom ...

(1266) had fixed the boundaries with the Kingdom of the Scots with England and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

respectively, its borders were close to the modern boundaries. After this time both Berwick and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

were lost to England, and Orkney and Shetland were gained from Norway in the fifteenth century.

The area that became Scotland in this period is divided by geology into five major regions: the Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands ( gd, Na Monaidhean a Deas) are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas (the other two being the Central Lowlands and the Grampian Mountains and the Highlands, as illustrate ...

, Central Lowlands

The Central Lowlands, sometimes called the Midland Valley or Central Valley, is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and ...

, the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

, the North-east coastal plain and the Islands

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

. Some of these were further divided by mountains, major rivers and marshes. Most of these regions had strong cultural and economic ties elsewhere: to England, Ireland, Scandinavian and mainland Europe. Internal communications were difficult and the country lacked an obvious geographical centre. Dunfermline

Dunfermline (; sco, Dunfaurlin, gd, Dùn Phàrlain) is a city, parish and former Royal Burgh, in Fife, Scotland, on high ground from the northern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city currently has an estimated population of 58,508. Acco ...

emerged as a major royal centre in the reign of Malcolm III and Edinburgh began to be used to house royal records in the reign of David I, but, perhaps because of its proximity and vulnerability to England, it did not become a formal capital in this period.

The expansion of Alba into the wider Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

was a gradual process combining external conquest and the suppression of occasional rebellions with the extension of seigniorial power through the placement of effective agents of the crown. Neighbouring independent kings became subject to Alba and eventually disappeared from the records. In the ninth century the term ''mormaer

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a ''Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continental c ...

'', meaning "great steward", began to appear in the records to describe the rulers of Moray, Strathearn

Strathearn or Strath Earn (, from gd, Srath Èireann) is the strath of the River Earn, in Scotland, extending from Loch Earn in the West to the River Tay in the east.http://www.strathearn.com/st_where.htm Derivation of name Strathearn was on ...

, Buchan

Buchan is an area of north-east Scotland, historically one of the original provinces of the Kingdom of Alba. It is now one of the six committee areas and administrative areas of Aberdeenshire Council, Scotland. These areas were created by ...

, Angus and Mearns, who may have acted as "marcher lords" for the kingdom to counter the Viking threat.Webster (1997) p. 22. Later the process of consolidation is associated with the feudalism introduced by David I, which, particularly in the east and south where the crown's authority was greatest, saw the placement of lordships, often based on castles, and the creation of administrative sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

doms, which overlay the pattern of local thegn

In Anglo-Saxon England, thegns were aristocratic landowners of the second rank, below the ealdormen who governed large areas of England. The term was also used in early medieval Scandinavia for a class of retainers. In medieval Scotland, there ...

s. It also saw the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

''earl'' and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''comes'' begin to replace the ''mormaers'' in the records. The result has been seen as a "hybrid kingdom, in which Gaelic, Anglo-Saxon, Flemish and Norman elements all coalesced under its 'Normanised', but nevertheless native lines of kings".Grant (1997) p. 97.

Economy and society

Economy

pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands ( pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

, rather than arable farming. Arable farming grew significantly in the "Norman period", but with geographical differences, low-lying areas being subject to more arable farming than high-lying areas such as the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

, Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

and the Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands ( gd, Na Monaidhean a Deas) are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas (the other two being the Central Lowlands and the Grampian Mountains and the Highlands, as illustrate ...

. Galloway, in the words of G. W. S. Barrow, "already famous for its cattle, was so overwhelmingly pastoral, that there is little evidence in that region of land under any permanent cultivation, save along the Solway coast". The average amount of land used by a husbandman in Scotland might have been around 26 acres

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

. The native Scots favoured pastoralism, in that Gaelic lords were happier to give away more land to French and Middle English-speaking settlers, while holding on tenaciously to upland regions, perhaps contributing to the Highland/Galloway-Lowland division that emerged in Scotland in the later Middle Ages. The main unit of land measurement in Scotland was the ''davoch'' (i.e. "vat"), called the ''arachor'' in Lennox and also known as the "Scottish ploughgate". In English-speaking Lothian, it was simply ploughgate. It may have measured about , divided into 4 ''rath''s. Cattle, pigs and cheeses were among the chief foodstuffs, from a wide range of produce including sheep, fish, rye, barley, bee wax and honey.

David I established the first chartered burghs

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

in Scotland, copying the burgher charters and ''Leges Burgorum'' (rules governing virtually every aspect of life and work) almost verbatim from the English customs of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

. Early burgesses were usually Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, rather than Gaelic Scots. The burgh's vocabulary was composed totally of either Germanic and French terms. The councils that ran individual burghs were individually known as ''lie doussane'', meaning the dozen.

Demography and language

The population of Scotland in this period is unknown. The first reliable information in 1755 shows the inhabitants of Scotland as 1,265,380. Best estimates put the Scottish population for earlier periods in the High Middle Ages between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people, growing from a low point to a high point. Linguistically, the majority of people within Scotland throughout this period spoke theGaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

language, then simply called ''Scottish'', or in Latin, ''lingua Scotica''. Other languages spoken throughout this period were Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

and English, with the Cumbric language