Sanhedrin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sanhedrin (

The Sanhedrin (

The Sanhedrin (

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: , ''synedrion A synedrion or synhedrion ( Greek: συνέδριον, "sitting together", hence " assembly" or "council"; he, סנהדרין, ''sanhedrin'') is an assembly that holds formal sessions. The Latinized form is synedrium.

Depending on the widely varie ...

'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s" after the destruction of the Second Temple), appointed to sit as a tribunal

A tribunal, generally, is any person or institution with authority to judge, adjudicate on, or determine claims or disputes—whether or not it is called a tribunal in its title.

For example, an advocate who appears before a court with a single ...

in every city in the ancient Land of Israel.

There were two classes of Rabbinite Jewish courts which were called Sanhedrin, the Great Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), a ...

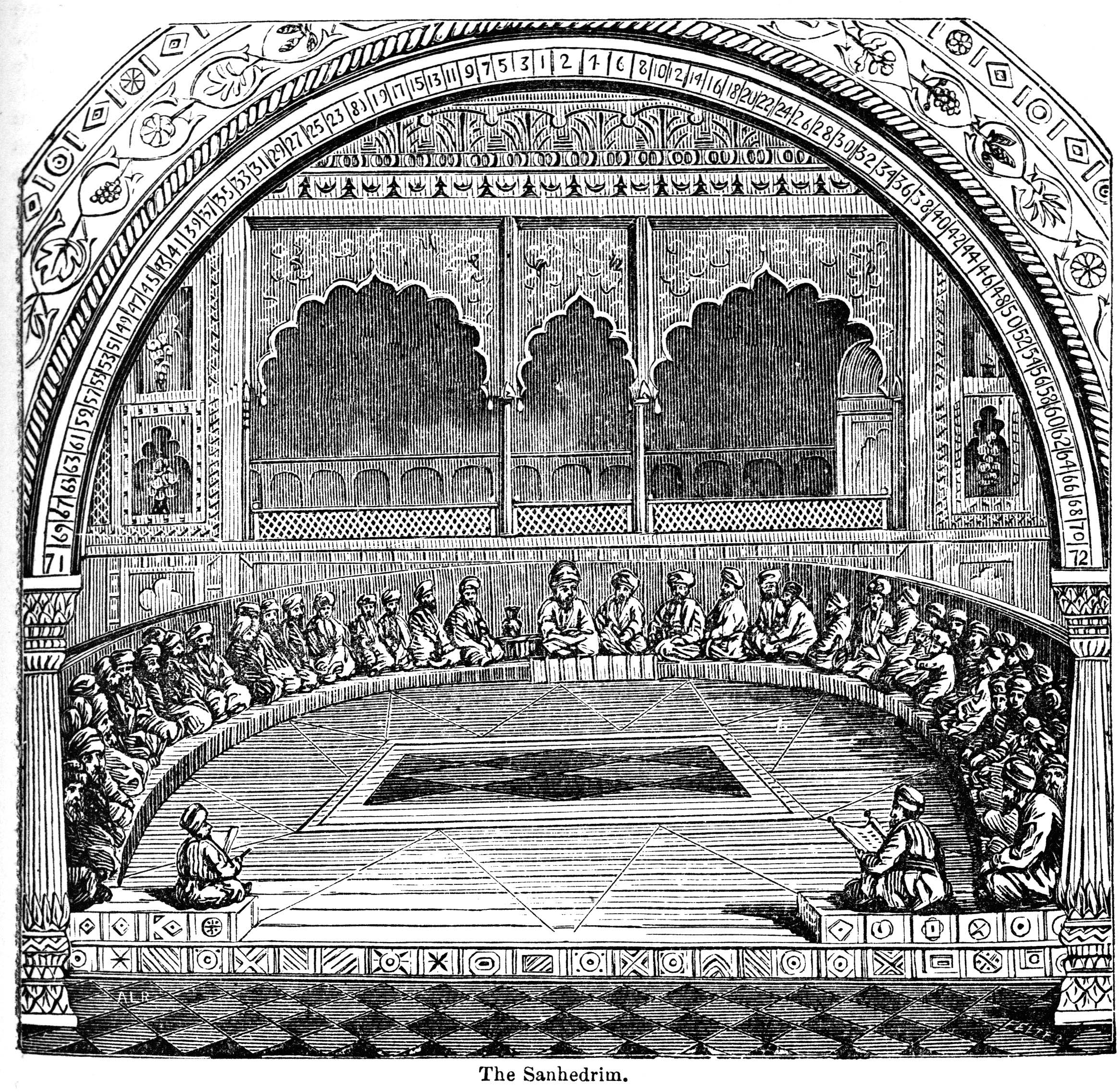

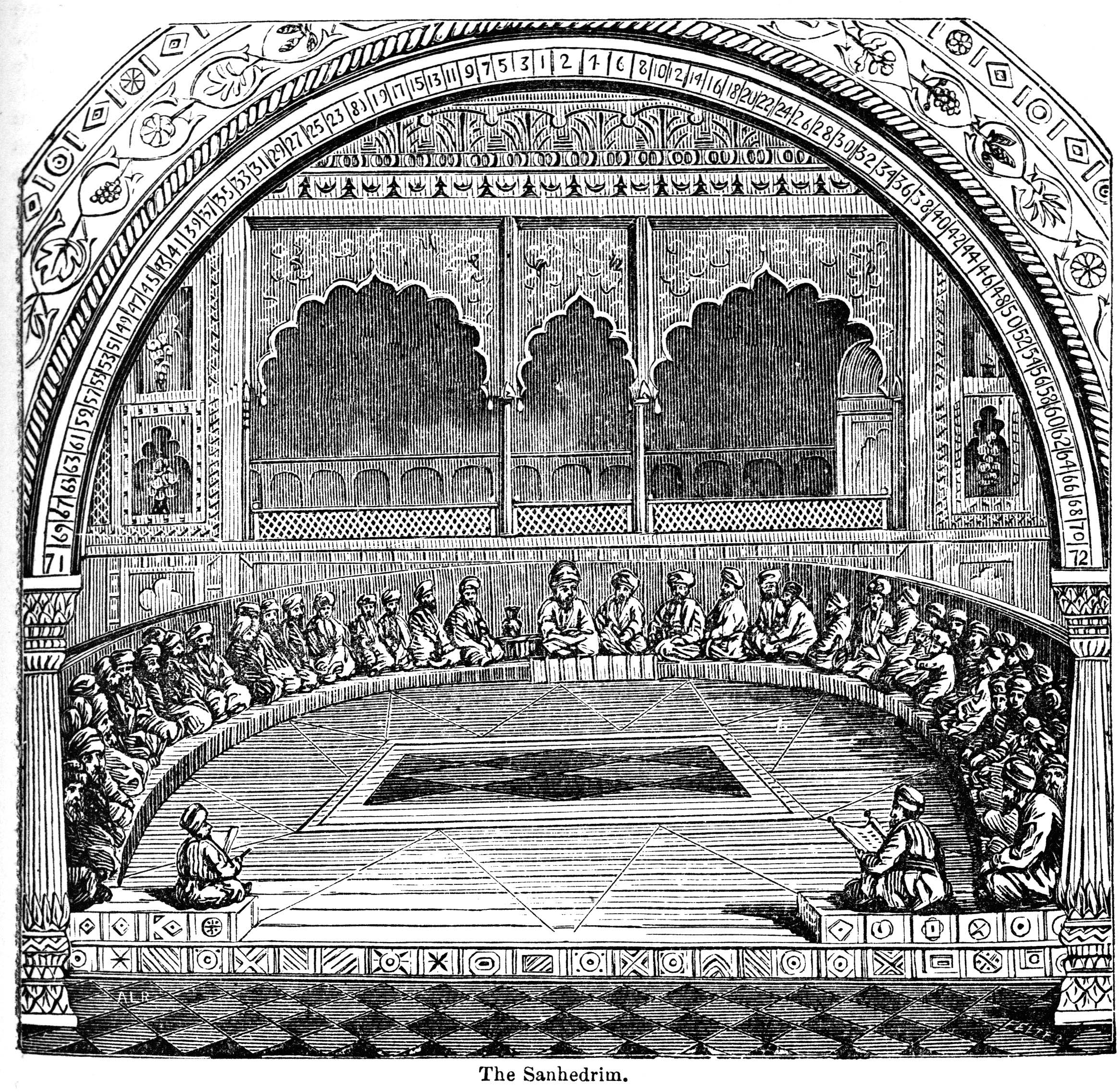

and the Lesser Sanhedrin. A lesser Sanhedrin of 23 judges was appointed to sit as a tribunal in each city, but there was only supposed to be one Great Sanhedrin of 71 judges, which among other roles acted as the Supreme Court, taking appeals from cases which were decided by lesser courts. In general usage, ''the Sanhedrin'' without qualifier normally refers to the Great Sanhedrin, which was presided over by the '' Nasi'', who functioned as its head or representing president, and was a member of the court; the '' Av Beit Din'' or the chief of the court, who was second to the ; and 69 general members.

In the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Temple in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, in a building called the Hall of Hewn Stones The Hall of Hewn Stones (Hebrew: לשכת הגזית ''Lishkat haGazit''), also known as the Chamber of Hewn Stone, was the meeting place, or council-chamber, of the Sanhedrin during the Second Temple period (6th century BCE – 1st century CE). The ...

. The Great Sanhedrin convened every day except festivals

A festival is an event ordinarily celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, mela, or eid. A festival c ...

and the sabbath day ( Shabbat).

After the destruction of the Second Temple and the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Great Sanhedrin moved to Galilee, which became part of the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In this period the Sanhedrin was sometimes referred as the ''Galilean Patriarchate'' or ''Patriarchate of Palaestina'', being the governing legal body of Galilean Jewry. In the late 200s CE, to avoid persecution, the name ''Sanhedrin'' was dropped and its decisions were issued under the name of (house of learning). The last universally binding decision of the Great Sanhedrin appeared in 358 CE, when the Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar ( he, הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, translit=HaLuah HaIvri), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance, and as an official calendar of the state of Israel. ...

was established. The Great Sanhedrin was finally disbanded in 425 CE after continued persecution by the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

.

Over the centuries, there have been attempts to revive the institution, such as the Grand Sanhedrin

The Grand Sanhedrin was a Jewish high court convened in Europe by Napoleon to give legal sanction to the principles expressed by an assembly of Jewish notables in answer to the twelve questions submitted to it by the government.Jew. Encyc. v. 468 ...

convened by Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, and modern attempts in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

Hebrew Bible

In theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Moses and the Israelites were commanded by God to establish courts of judges who were given full authority over the people of Israel, who were commanded by God through Moses to obey the judgments made by the courts and every Torah-abiding law they established. Judges in ancient Israel were the religious leaders and

Rabbinic texts indicate that following the Bar Kokhba revolt, southern Galilee became the seat of rabbinic learning in the Land of Israel. This region was the location of the court of the Patriarch which was situated first at Usha, then at

Rabbinic texts indicate that following the Bar Kokhba revolt, southern Galilee became the seat of rabbinic learning in the Land of Israel. This region was the location of the court of the Patriarch which was situated first at Usha, then at

"Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE"

an

. As a reaction against Julian's pro-Jewish stance, the later emperor

/ref> in Jerusalem under the Caliph 'Umar, and in Babylon (Iraq), but none of these attempts were given any attention by Rabbinic authorities and little information is available about them.

The "Grand Sanhedrin" was a Jewish high court convened by

The "Grand Sanhedrin" was a Jewish high court convened by

Sanhedrin Launched in Tiberias Israel National News January 20, 2005

/ref> where the original Sanhedrin was disbanded, in which it claimed to re-establish the body according to the proposal of

Secular and religious history of the Jewish Sanhedrin

English web site of the re-established Jewish Sanhedrin in Israel

by Rabbi

''Jewish Encyclopedia'': "Sanhedrin"

* {{Jewish history 1st-century BC establishments in the Hasmonean Kingdom 420s disestablishments in the Roman Empire Governing assemblies of religious organizations Historical legislatures Jewish courts and civil law Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire Jews and Judaism in the Byzantine Empire Judaism-related controversies Rabbinical organizations Hasmonean Kingdom

'' Moses and the Israelites were commanded by God to establish courts of judges who were given full authority over the people of Israel, who were commanded by God through Moses to obey the judgments made by the courts and every Torah-abiding law they established. Judges in ancient Israel were the religious leaders and

teachers

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. wh ...

of the nation of Israel. The Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

(Sanhedrin 1:6) arrives at the number twenty-three based on an exegetical derivation: it must be possible for a "community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, ...

" to vote for both conviction and exoneration (). The minimum size of a "community" is 10 men, thus 10 vs 10. One more is required to achieve a majority (11 vs. 10), but a simple majority cannot convict (), and so an additional judge is required (12 vs. 10). Finally, a court should not have an even number of judges to prevent deadlocks; thus 23 (12 vs. 10 and 1). This court dealt with only religious matters. In regard to the Sanhedrin of 70 Elders to help Moses, years before in Egypt these men had been Hebrew officials under Egyptian taskmasters; they were beaten by the Egyptians when they refused to beat fellow Jews in order to finish building projects. As a reward they became the Sanhedrin of 70 Elders.

History

Early Sanhedrin

The Hasmonean court inJudea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous sou ...

, presided over by Alexander Jannaeus

Alexander Jannaeus ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξανδρος Ἰανναῖος ; he, ''Yannaʾy''; born Jonathan ) was the second king of the Hasmonean dynasty, who ruled over an expanding kingdom of Judea from 103 to 76 BCE. A son of John Hyrcanus, ...

, until 76 BCE, followed by his wife, Queen Salome Alexandra

Salome Alexandra, or Shlomtzion ( grc-gre, Σαλώμη Ἀλεξάνδρα; he, , ''Šəlōmṣīyyōn''; 141–67 BCE), was one of three women to rule over Judea, the other two being Athaliah and Devora. The wife of Aristobulus I, and ...

, was called or ''Sanhedrin.'' The exact nature of this early Sanhedrin is not clear. It may have been a body of sages or priests, or a political, legislative and judicial institution. The first historical record of the body was during the administration of Aulus Gabinius

Aulus Gabinius (by 101 BC – 48 or 47 BC) was a Roman statesman and general. He was an avid supporter of Pompey who likewise supported Gabinius. He was a prominent figure in the latter days of the Roman Republic.

Career

In 67 BC, when trib ...

, who, according to Josephus, organized five in 57 BCE as Roman administration was not concerned with religious affairs unless sedition was suspected. Only after the destruction of the Second Temple was the Sanhedrin made up only of sages.

Herodian and early Roman rule

The first historic mention of a '' Synhedrion'' (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: ) occurs in the Psalms of Solomon (XVII:49), a Jewish religious book written in Greek.

The Mishnah tractate Sanhedrin (IV:2) states that the Sanhedrin was to be recruited from the following sources: Priests (Kohanim), Levites (Levi'im), and ordinary Jews who were members of those families having a pure lineage such that their daughters were allowed to marry priests.

In the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Hall of Hewn Stones The Hall of Hewn Stones (Hebrew: לשכת הגזית ''Lishkat haGazit''), also known as the Chamber of Hewn Stone, was the meeting place, or council-chamber, of the Sanhedrin during the Second Temple period (6th century BCE – 1st century CE). The ...

in the Temple in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. The court convened every day except festivals

A festival is an event ordinarily celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, mela, or eid. A festival c ...

and the sabbath day ( Shabbat).

The trial of Jesus, and early Christianity

A is mentioned 22 times in the GreekNew Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

, including in the Gospels in relation to the trial of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, and in the '' Acts of the Apostles'', which mentions a "Great " in chapter 5 where rabbi Gamaliel

Gamaliel the Elder (; also spelled Gamliel; he, רַבַּן גַּמְלִיאֵל הַזָּקֵן ''Rabban Gamlīʾēl hazZāqēn''; grc-koi, Γαμαλιὴλ ὁ Πρεσβύτερος ''Gamaliēl ho Presbýteros''), or Rabban Gamaliel I, ...

appeared, and also in chapter 7 in relation to the stoning death of Saint Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

.

During Jewish–Roman Wars

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the Sanhedrin was re-established inYavneh

Yavne ( he, יַבְנֶה) or Yavneh is a city in the Central District of Israel. In many English translations of the Bible, it is known as Jabneh . During Greco-Roman times, it was known as Jamnia ( grc, Ἰαμνία ''Iamníā''; la, Iamnia) ...

with reduced authority. The seat of the Patriarchate moved to Usha under the presidency of Gamaliel II

Rabban Gamaliel II (also spelled Gamliel; he, רבן גמליאל דיבנה; before -) was a rabbi from the second generation of tannaim. He was the first person to lead the Sanhedrin as '' nasi'' after the fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

...

in 80 CE. In 116 it moved back to Yavneh, and then again back to Usha.

After Bar Kokhba Revolt

Rabbinic texts indicate that following the Bar Kokhba revolt, southern Galilee became the seat of rabbinic learning in the Land of Israel. This region was the location of the court of the Patriarch which was situated first at Usha, then at

Rabbinic texts indicate that following the Bar Kokhba revolt, southern Galilee became the seat of rabbinic learning in the Land of Israel. This region was the location of the court of the Patriarch which was situated first at Usha, then at Bet Shearim

Beit She'arim ( he, בֵּית שְׁעָרִים, "House of Gates") is the currently used name for the ancient Jewish town of Beit She'arim (Roman-era Jewish village), Bet She'arayim (, "House of Two Gates") or ''Kfar She'arayim'' (, "Villa ...

, later at Sepphoris and finally at Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

.

The Great Sanhedrin moved in 140 to Shefaram

Shefa-Amr, also Shfar'am ( ar, شفاعمرو, Šafāʻamr, he, שְׁפַרְעָם, Šəfarʻam) is an Arab city in the Northern District of Israel. In it had a population of , with a Sunni Muslim majority and large Christian Arab and Druze m ...

under the presidency of Shimon ben Gamliel II

Simeon (or Shimon) ben Gamaliel II (Hebrew: ) was a Tannaim, Tanna of the third generation and president of the Great Sanhedrin. He was the son of Gamaliel II.

Biography

Simeon was a youth in Betar (fortress), Betar when the Bar Kokhba revolt bro ...

, and subsequently to Beit She'arim (Roman-era Jewish village) and later to Sepphoris, under the presidency of Judah ha-Nasi

Judah ha-Nasi ( he, יְהוּדָה הַנָּשִׂיא, ''Yəhūḏā hanNāsīʾ''; Yehudah HaNasi or Judah the Prince) or Judah I, was a second-century rabbi (a tanna of the fifth generation) and chief redactor and editor of the ''Mis ...

. Finally, it moved to Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

in 220, under the presidency of Gamaliel III (220–230), a son of Judah ha-Nasi, where it became more of a consistory, but still retained, under the presidency of Judah II (230–270), the power of excommunication.

During the presidency of Gamaliel IV (270–290), due to Roman persecution, it dropped the name Sanhedrin; and its authoritative decisions were subsequently issued under the name of '' Beth HaMidrash''.

In the year 363, the emperor Julian (r. 355–363 CE), an apostate from Christianity, ordered the Temple rebuilt. The project's failure has been ascribed to the Galilee earthquake of 363, and to the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s' ambivalence about the project. Sabotage is a possibility, as is an accidental fire. Divine intervention was the common view among Christian historians of the time.Se"Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE"

an

. As a reaction against Julian's pro-Jewish stance, the later emperor

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

(r. 379–395 CE) forbade the Sanhedrin to assemble and declared ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

illegal. Capital punishment was prescribed for any Rabbi who received ordination, as well as complete destruction of the town where the ordination occurred.

However, since the Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar ( he, הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, translit=HaLuah HaIvri), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance, and as an official calendar of the state of Israel. ...

was based on witnesses' testimony, which had become far too dangerous to collect, rabbi Hillel II

Hillel II (Hebrew: הלל נשיאה, Hillel the Nasi), also known simply as Hillel, was an '' amora'' of the fifth generation in the Land of Israel. He held the office of '' Nasi'' of the Sanhedrin between 320 and 385 CE. He was the son and succ ...

recommended change to a mathematically based calendar that was adopted at a clandestine, and maybe final, meeting in 358 CE. This marked the last universal decision made by the Great Sanhedrin.

Gamaliel VI Gamaliel VI (c. 370–425) was the last '' nasi'' of the ancient Sanhedrin.

Gamaliel came into office around the year 400. On October 20, 415, an edict issued by the Emperors Honorius and Theodosius II stripped Gamaliel of his rank of honorary ...

(400–425) was the Sanhedrin's last president. With his death in 425, Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

outlawed the title of Nasi, the last remains of the ancient Sanhedrin. An imperial decree of 426 diverted the patriarchs' tax () into the imperial treasury. The exact reason for the abrogation of the patriarchate is not clear, though Gamaliel VI, the last holder of the office who had been for a time elevated by the emperor to the rank of prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

, may have fallen out with the imperial authorities. Thereafter, Jews were gradually excluded from holding public office.

Powers

The Talmud tractate Sanhedrin identifies two classes of rabbinical courts called Sanhedrin, a Great Sanhedrin () and a Lesser Sanhedrin (). Each city could have its own lesser Sanhedrin of 23 judges, but there could be only one Great Sanhedrin of 71, which among other roles acted as the Supreme Court, taking appeals from cases decided by lesser courts. The uneven numbers of judges were predicated on eliminating the possibility of a tie, and the last to cast his vote was the head of the court.Function and procedures

The Sanhedrin as a body claimed powers that lesser Jewish courts did not have. As such, they were the only ones who could try the king, extend the boundaries of the Temple and Jerusalem, and were the ones to whom all questions of law were finally put. Before 191 BCE the High Priest acted as the ''ex officio'' head of the Sanhedrin,Goldwurm, Hersh and Holder, Meir, ''History of the Jewish People'', I "The Second Temple Era" (Mesorah Publications

ArtScroll is an imprint of translations, books and commentaries from an Orthodox Jewish perspective published by Mesorah Publications, Ltd., a publishing company based in Rahway, New Jersey. Rabbi Nosson Scherman is the general editor.

ArtScroll ...

: 1982) . but in 191 BCE, when the Sanhedrin lost confidence in the High Priest, the office of ''Nasi'' was created. After the time of Hillel the Elder (late 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE), the Nasi was almost invariably a descendant of Hillel. The second highest-ranking member of the Sanhedrin was called the '' Av Beit Din'', or 'Head of the Court' (literally, means 'father of the house of judgment'), who presided over the Sanhedrin when it sat as a criminal court.

During the Second Temple period, the Sanhedrin met in a building known as the Hall of Hewn Stones The Hall of Hewn Stones (Hebrew: לשכת הגזית ''Lishkat haGazit''), also known as the Chamber of Hewn Stone, was the meeting place, or council-chamber, of the Sanhedrin during the Second Temple period (6th century BCE – 1st century CE). The ...

(), which has been placed by the Talmud and many scholars as built into the northern wall of the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount ( hbo, הַר הַבַּיִת, translit=Har haBayīt, label=Hebrew, lit=Mount of the House f the Holy}), also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, lit. 'The Noble Sanctuary'), al-Aqsa Mosque compou ...

, half inside the sanctuary and half outside, with doors providing access variously to the Temple and to the outside. The name presumably arises to distinguish it from the buildings in the Temple complex used for ritual purposes, which could not be constructed of stones hewn by any iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

implement.

In some cases, it was necessary only for a 23-member panel (functioning as a Lesser Sanhedrin) to convene. In general, the full panel of 71 judges was convened only on matters of national significance (''e.g.'', a declaration of war) or when the 23-member panel failed to reach a conclusive verdict.

By the end of the Second Temple period, the Sanhedrin reached its pinnacle of importance, legislating all aspects of Jewish religious and political life within parameters laid down by Biblical and Rabbinic tradition.

Summary of Patriarchal powers

The following is a summary of the powers and responsibilities of the Patriarchate from the onset of the third century, based on rabbinic sources as understood by L.I. Levine: #Representative to Imperial authorities; #Focus of leadership in the Jewish community: ##Receiving daily visits from prominent families; ##Declaration of public fast days; ##Initiating or abrogating the ban ('' herem''); #Appointment of judges to Jewish courts in the Land of Israel; #Regulation of the calendar; #Issuing enactments and decrees with respect to the applicability or release from legal requirements, e.g.: ##Use ofsabbatical year

A sabbatical (from the Hebrew: (i.e., Sabbath); in Latin ; Greek: ) is a rest or break from work.

The concept of the sabbatical is based on the Biblical practice of ''shmita'' (sabbatical year), which is related to agriculture. According to ...

produce and applicability of sabbatical year injunctions;

##Repurchase or redemption of formerly Jewish land from gentile owners;

##Status of Hellenistic cities of the Land of Israel re: purity, tithing, sabbatical year;

##Exemptions from tithing;

##Conditions in divorce documents;

##Use of oil produced by gentiles;

#Dispatching emissaries to diaspora communities;

#Taxation: both the power to tax and the authority to rule/intervene on the disposition of taxes raised for local purposes by local councils.

Up to the middle of the fourth century, the Patriarchate retained the prerogative of determining the Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar ( he, הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, translit=HaLuah HaIvri), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance, and as an official calendar of the state of Israel. ...

and guarded the intricacies of the needed calculations, in an effort to constrain interference by the Babylonian community. Christian persecution obliged Hillel II

Hillel II (Hebrew: הלל נשיאה, Hillel the Nasi), also known simply as Hillel, was an '' amora'' of the fifth generation in the Land of Israel. He held the office of '' Nasi'' of the Sanhedrin between 320 and 385 CE. He was the son and succ ...

to fix the calendar in permanent form in 359 CE. This institution symbolized the passing of authority from the Patriarchate to the Babylonian Talmudic academies.

Archaeological findings

In 2004, excavations in Tiberias conducted by theIsrael Antiquities Authority

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA, he, רשות העתיקות ; ar, داﺌرة الآثار, before 1990, the Israel Department of Antiquities) is an independent Israeli governmental authority responsible for enforcing the 1978 Law of ...

uncovered a structure dating to the 3rd century CE that may have been the seat of the Sanhedrin when it convened in that city. At the time it was called .

Nasi (president)

Before 191 BCE the High Priest acted as the ''ex officio'' head of the Sanhedrin, but in 191 BCE, when the Sanhedrin lost confidence in the High Priest, the office of Nasi was created. The Sanhedrin was headed by the chief scholars of the great Talmudic Academies in the Land of Israel, and with the decline of the Sanhedrin, their spiritual and legal authority was generally accepted, the institution itself being supported by voluntary contributions by Jews throughout the ancient world. Being a member of the house of Hillel and thus a descendant of King David, the Patriarch, known in Hebrew as the '' Nasi'' (prince), enjoyed almost royal authority. Their functions were political rather than religious, though their influence was not limited to the secular realm. The Patriarchate attained its zenith underJudah ha-Nasi

Judah ha-Nasi ( he, יְהוּדָה הַנָּשִׂיא, ''Yəhūḏā hanNāsīʾ''; Yehudah HaNasi or Judah the Prince) or Judah I, was a second-century rabbi (a tanna of the fifth generation) and chief redactor and editor of the ''Mis ...

who compiled the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

, a compendium of views from Judean thought leaders of Judaism other than the Torah.

Revival attempts

The Sanhedrin is traditionally viewed as the last institution that commanded universal authority among the Jewish people in the long chain of tradition from Moses until the present day. Since its dissolution in 358 CE by imperial decree, there have been several attempts to re-establish this body either as a self-governing body, or as a puppet of a sovereign government. There are records of what may have been attempts to reform the Sanhedrin in Arabia,The Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614 compared with Islamic conquest of 638/ref> in Jerusalem under the Caliph 'Umar, and in Babylon (Iraq), but none of these attempts were given any attention by Rabbinic authorities and little information is available about them.

Napoleon Bonaparte's "Grand Sanhedrin"

The "Grand Sanhedrin" was a Jewish high court convened by

The "Grand Sanhedrin" was a Jewish high court convened by Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

to give legal sanction to the principles expressed by the Assembly of Notables in answer to the twelve questions submitted to it by the government (see ''Jew. Encyc. v. 468, s.v. France'').

On October 6, 1806, the Assembly of Notables issued a proclamation to all the Jewish communities of Europe, inviting them to send delegates to the Sanhedrin, to convene on October 20. This proclamation, written in Hebrew, French, German, and Italian, speaks in extravagant terms of the importance of this revived institution and of the greatness of its imperial protector. While the action of Napoleon aroused in many Jews of Germany the hope that, influenced by it, their governments also would grant them the rights of citizenship, others looked upon it as a political contrivance. When in the war against Prussia (1806–07) the emperor invaded Poland and the Jews rendered great services to his army, he remarked, laughing, "The sanhedrin is at least useful to me." David Friedländer and his friends in Berlin described it as a spectacle that Napoleon offered to the Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

ians.

State of Israel

Since the dissolution of the Sanhedrin in 358 CE, there has been no universally recognized authority withinHalakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

. Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

(1135–1204) was one of the greatest scholars of the Middle Ages, and is arguably one of the most widely accepted scholars among the Jewish people since the closing of the Talmud in 500. Influenced by the rationalist school of thought and generally showing a preference for a natural (as opposed to miraculous) redemption for the Jewish people, Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

proposed a rationalist solution for achieving the goal of re-establishing the highest court in Jewish tradition and reinvesting it with the same authority it had in former years. There have been several attempts to implement Maimonides' recommendations, the latest being in modern times.

There have been rabbinical attempts to renew Semicha

Semikhah ( he, סמיכה) is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

The original ''semikhah'' was the formal "transmission of authority" from Moses through the generations. This form of ''semikhah'' ceased between 360 and 425 C ...

and re-establish a Sanhedrin by Rabbi Jacob Berab

Jacob Berab ( he, יעקב בירב), also spelled Berav or Bei-Rav, (1474 – April 3, 1546), was an influential rabbi and talmudist best known for his attempt to reintroduce classical semikhah (ordination).

Biography

Berab was born at Maqueda ...

in 1538, Rabbi Yisroel Shklover in 1830, Rabbi Aharon Mendel haCohen in 1901, Rabbi Zvi Kovsker in 1940 and Rabbi Yehuda Leib Maimon

Yehuda Leib Maimon ( he, יהודה לייב מימון, 11 December 1875 – 10 July 1962, also known as Yehuda Leib HaCohen Maimon) was an Israeli rabbi, politician and leader of the Religious Zionist movement. He was Israel's first Minis ...

in 1949.

In October 2004 (Tishrei 5765), a group of rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s representing varied Orthodox communities in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

undertook a ceremony in Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

,/ref> where the original Sanhedrin was disbanded, in which it claimed to re-establish the body according to the proposal of

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

and the Jewish legal rulings of Rabbi Yosef Karo

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, also spelled Yosef Caro, or Qaro ( he, יוסף קארו; 1488 – March 24, 1575, 13 Nisan 5335 A.M.), was the author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the '' Beit Yosef'', and its popular analogue, the ''Shu ...

. The controversial attempt has been subject to debate within different Jewish communities.

See also

* Council of Jamnia * Beth din shel Kohanim * Great Assembly – or ('Men of the Great Assembly') *Magnum Concilium

In the Kingdom of England, the (Latin for "Great Council") was an assembly historically convened at certain times of the year when the English baronage and church leaders were summoned to discuss the affairs of the country with the king. In the ...

, a similar body in medieval England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

* Synedrion A synedrion or synhedrion ( Greek: συνέδριον, "sitting together", hence " assembly" or "council"; he, סנהדרין, ''sanhedrin'') is an assembly that holds formal sessions. The Latinized form is synedrium.

Depending on the widely varie ...

, a general term for judiciary organs of Greek and Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

city states and treaty organisations.

* Tombs of the Sanhedrin

References

Bibliography

*Chen, S.J.D., ''"Patriarchs and Scholarchs,"'' PAAJR 48 (1981), 57–85. *Goodman, M., ''"The Roman State and the Jewish Patriarch in the Third Century,"'' in L.I. Levnie (ed.), ''The Galilee in late Antiquity'' (New York, 1992), 127.39. *Habas (Rubin), E., ''"Rabban Gamaliel of Yavneh and his Sons: The Patriarchate before and after the Bar Kokhva Revolt,"'' JJS 50 (1999), 21–37. *Levine, L.I., ''"The Patriarch (Nasi) in Third-Century Palestine,"'' ANRW 2.19.2 (1979), 649–88.External links

Secular and religious history of the Jewish Sanhedrin

English web site of the re-established Jewish Sanhedrin in Israel

by Rabbi

Aryeh Kaplan

Aryeh Moshe Eliyahu Kaplan ( he, אריה משה אליהו קפלן; October 23, 1934 – January 28, 1983) was an American Orthodox rabbi, author, and translator, best known for his Living Torah edition of the Torah. He became well known as ...

''Jewish Encyclopedia'': "Sanhedrin"

* {{Jewish history 1st-century BC establishments in the Hasmonean Kingdom 420s disestablishments in the Roman Empire Governing assemblies of religious organizations Historical legislatures Jewish courts and civil law Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire Jews and Judaism in the Byzantine Empire Judaism-related controversies Rabbinical organizations Hasmonean Kingdom