Samuel Werenfels on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

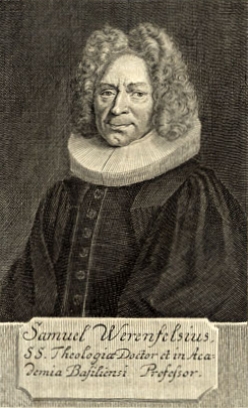

Samuel Werenfels (; 1 March 1657 – 1 June 1740) was a

Samuel Werenfels (; 1 March 1657 – 1 June 1740) was a

archive.org

During the last twenty years of his life he lived in retirement. He took part in the proceedings against

Hic liber est in quo sua quærit dogmata quisque,

Invenit et pariter dogmata quisque sua.

He advocated instead the

Google Books

The "triumvirate" position on

Spenserians page

Google Books

*Wolfgang Rother, ''Paratus sum sententiam mutare: The Influence of Cartesian Philosophy at Basle'' pp. 71–97, History of Universities, Volume XXII/1 (2007)

Google Books

* Werner Raupp: Werenfels, Samuel, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS; also in French and Italian), Vol. 13 (2014), p. 407–408 (also online: http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D10910.php). Attribution: *

Google Books

WorldCat pageCERL pageOnline Books page

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Werenfels, Samuel 1657 births 1740 deaths People from Basel-Stadt Swiss Calvinist and Reformed theologians 17th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 18th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 17th-century Swiss writers

Samuel Werenfels (; 1 March 1657 – 1 June 1740) was a

Samuel Werenfels (; 1 March 1657 – 1 June 1740) was a Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

theologian. He was a major figure in the move towards a "reasonable orthodoxy" in Swiss Reformed theology

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

.

Life

Werenfels was born atBasel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

in the Old Swiss Confederacy

The Old Swiss Confederacy or Swiss Confederacy (German language, Modern German: ; historically , after the Swiss Reformation, Reformation also , "Confederation of the Swiss") was a loose confederation of independent small states (, German or ...

, the son of archdeacon Peter Werenfels and Margaretha Grynaeus. After finishing his theological and philosophical studies at Basel, he visited the universities at Zurich, Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

, Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR-74), ...

, and Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

. On his return he took on the duties, for a short time, of the professorship of logic, for Samuel Burckhardt. In 1685 he became professor of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

at Basel.

.

In 1686 Werenfels undertook an extensive journey through Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, one of his companions being Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet (18 September 1643 – 17 March 1715) was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was highly respected as a cleric, a preacher, an academic, ...

. In 1687 he was appointed professor of rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

, and in 1696 became a member of the theological faculty, occupying successively, according to the Basel custom, the chairs of dogmatic

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Isla ...

s and polemics

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

, Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, and New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

.

Werenfels received a call from the University of Franeker

The University of Franeker (1585–1811) was a university in Franeker, Friesland, the Netherlands. It was the second oldest university of the Netherlands, founded shortly after Leiden University.

History

Also known as ''Academia Franekerensis'' ...

, but rejected it. In 1722 he led a successful move to have the ''Helvetic Consensus

The Helvetic Consensus ( la, Formula consensus ecclesiarum Helveticarum) is a Swiss Reformed tradition, Reformed profession of faith drawn up in 1675 to guard against doctrines taught at the French Academy of Saumur, especially Amyraldism.

Origin ...

'' set aside in Basel, as divisive. He was member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organization (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Part ...

of London. James Isaac Good, ''History of the Swiss Reformed Church since the Reformation'' (1913), p. 172archive.org

During the last twenty years of his life he lived in retirement. He took part in the proceedings against

Johann Jakob Wettstein

Johann Jakob Wettstein (also Wetstein; 5 March 1693 – 23 March 1754) was a Swiss theologian, best known as a New Testament critic.

Biography

Youth and study

Johann Jakob Wettstein was born in Basel. Among his tutors in theology was Samuel We ...

for heresy, but expressed regret afterwards at having become involved. He died in Basel.

Views of the "triumvirate"

Werenfels represented a theology that put doctrinal quibbles in the background. His epigram on the misuse of theBible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

is well known as: "This is the book in which each both seeks and finds his own dogmas." In the Latin original it is

historical-grammatical method

The historical-grammatical method is a modern Christian hermeneutical method that strives to discover the biblical authors' original intended meaning in the text. According to the historical-grammatical method, if based on an analysis of the gram ...

.

With Jean-Alphonse Turrettini

Jean-Alphonse Turrettini (August 1671 – May 1737) was a theologian from the Republic of Geneva.Turrettini Je ...

and Jean-Frédéric Osterwald

Jean-Frédéric Osterwald (or Ostervald) (25 November 1663 – 14 April 1747) was a Protestant pastor from Neuchâtel (now in Switzerland).

Life

He was born at Neuchâtel in 1663 in a patrician family, a son of the Reformed pastor Johann Rudolf O ...

, Werenfels made up what has been called a "Helvetic triumvirate", or "Swiss triumvirate", of moderate but orthodox Swiss Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

theologians. Their approach began to converge with the Dutch Remonstrant

The Remonstrants (or the Remonstrant Brotherhood) is a Protestant movement that had split from the Dutch Reformed Church in the early 17th century. The early Remonstrants supported Jacobus Arminius, and after his death, continued to maintain his ...

s, and the English latitudinarians. Their views promoted simple practical beliefs, rationality and tolerance. They were later charged with being a "Remonstrant trio", and Jan Jacob Schultens defended them. The three in fact admired the "reasonable orthodoxy" of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, and Turrettini in particular opposed with success the ''Helvetic Consensus''; but Werenfels made the first effective move against it. The triumvirate corresponded with William Wake

William Wake (26 January 165724 January 1737) was a priest in the Church of England and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1716 until his death in 1737.

Life

Wake was born in Blandford Forum, Dorset, and educated at Christ Church, Oxford. He took ...

, amongst other Protestant churchmen.

Works

Logomachy

Adriaan Heereboord

Adriaan Heereboord (13 October 1613 in Leiden – 7 July 1661 in Leiden) was a Dutch philosopher and logician.

Life

He was born in Leiden and graduated from the University of Leiden, where he had the chair of philosophy from 1643. :de:s:ADB:Heereb ...

had argued in Cartesian Cartesian means of or relating to the French philosopher René Descartes—from his Latinized name ''Cartesius''. It may refer to:

Mathematics

*Cartesian closed category, a closed category in category theory

*Cartesian coordinate system, modern ...

style, against scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

for limitations to be put on disputation

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations (in Latin: ''disputationes'', singular: ''disputatio'') offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed ru ...

, which should be bounded by good faith in the participants. Werenfels went further, regarding "logomachy" as a malaise of the Republic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (''Respublica literaria'') is the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas. It fostered communication among the intellectuals of the Age of Enlightenment, or ''phil ...

.Wolfgang Rother, ''Paratus sum sententiam mutare: The Influence of Cartesian Philosophy at Basle'' pp. 79–80, in ''History of Universities'', Volume XXII/1 (2007), pp. 79–80Google Books

The "triumvirate" position on

ecumenism

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

was based on the use of fundamental articles through the forum of the Republic of Letters.

The underlying causes of logomachy were taken by Werenfels to be prejudice and other failings of the disputants, and ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning in which a phrase, statement or resolution is not explicitly defined, making several interpretations plausible. A common aspect of ambiguity is uncertainty. It is thus an attribute of any idea or statement ...

in language. In his dissertation ''De logomachiis eruditorum'' (Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

, 1688) Werenfels argued that controversies that divide Christians are often verbal disputes, arising from moral deficiencies, especially from pride. He proposed to do away with them by making a universal lexicon of all terms and concepts.

In the ''Oratio de vero et falso theologorum zelo'' he admonished those who fight professedly for purity of doctrine, but in reality for their own system. He considers it the duty of the polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

ist not to combat antiquated heresies

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and to warm up dead issues, but to overthrow the prevalent enemies of true Christian living.

Theology

In 1699 he published anonymously ''Judicium de argumento Cartesii pro existentia Dei''. It was an acceptance in particular of the proof of existence of God from the third ''Meditation'' of Descartes; and in general of Cartesian philosophical premises. His conception of his duties as a theological professor was shown in his address, ''De scopo doctoris in academia sacras litteras docentis''. He believed that it was more important to care for the piety of candidates for the ministry, than for their scholarship. It was his belief that a professor of practical theology is as necessary as a professor of practicalmedicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

.

He stood for the necessity of a special revelation of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

, and defended the Biblical miracles as confirmations of the words of the evangelists. In his ''Cogitationes generales de ratione uniendi ecclesias protestantes, quae vulgo Lutheranarum et Reformatorum nominibus distingui solent'', he sought a way of reconciling Lutherans and Calvinists.

The ''De jure in conscientias ab homine non usurpando'' dated from 1702; it was written after Nicolaus Wil(c)kens had defended a thesis on religious freedom

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

in the absence of consequences for public order

In criminology, public-order crime is defined by Siegel (2004) as "crime which involves acts that interfere with the operations of society and the ability of people to function efficiently", i.e., it is behaviour that has been labelled criminal ...

, and defends freedom of conscience

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by ...

. The work met the approval of Benjamin Hoadly

Benjamin Hoadly (14 November 1676 – 17 April 1761) was an English clergyman, who was successively Bishop of Bangor, of Hereford, of Salisbury, and finally of Winchester. He is best known as the initiator of the Bangorian Controversy.

Li ...

and Samuel Haliday

Samuel Haliday or Hollyday (1685–1739) was an Irish Presbyterian non-subscribing minister, to the "first congregation" of Belfast.

Life

He was son of the Rev. Samuel Haliday (or Hollyday) (1637–1724), who was ordained presbyterian minister of ...

, while being used by Daniel Gerdes to attack Johannes Stinstra.

Collections

His ''Dissertationum theologicarum sylloge'' appeared first Basel, 1709; a further collection of his works is ''Opuscula theologica, philologica, et philosophica'' (Basel, 1718, new ed., 3 vols., 1782).Sermons, dissertations, translations

From 1710 Werenfels (a native speaker of German) was asked to preach sermons in the French church at Basel; they were in a plain style. As a preacher he has been described as "estranged from false pathos, elegant, intelligible, and edifying". These sermons were published as ''Sermons sur des verités importantes de la religion auxquels on ajoute des Considerations sur la reünion des protestans'' (1715). They were translated intoGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, and into Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

by Marten Schagen. Schagen also translated the ''De recto theologi zelo'' into Dutch.

The ''De logomachiis eruditorum'' was translated into English as ''Discourse of Logomachys, or Controversys about Words'' (1711). Thomas Herne under a pseudonym translated Latin and French works as ''Three Discourses'' (1718), at the time of the Bangorian Controversy. William Duncombe

William Duncombe (19 January 1690 – 26 February 1769) was a British author and playwright.

Life

Duncombe worked in the Navy Office from 1706 until 1725. That year, he and Elizabeth Hughes won a very large lottery sum on a joint ticket. He mar ...

translated ''An Oration on the Usefulness of Dramatic Interludes in the Education of Youth'' (1744). John Nichols, ''Literary Anecdotes of the XVIII Century'' (1812–15) vol. 8, pp. 265–70Spenserians page

Notes

References

*Joris van Eijnatten (2003), ''Liberty and Concord in the United Provinces: religious toleration and the public in the eighteenth-century Netherlands'' (2003)Google Books

*Wolfgang Rother, ''Paratus sum sententiam mutare: The Influence of Cartesian Philosophy at Basle'' pp. 71–97, History of Universities, Volume XXII/1 (2007)

Google Books

* Werner Raupp: Werenfels, Samuel, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS; also in French and Italian), Vol. 13 (2014), p. 407–408 (also online: http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/d/D10910.php). Attribution: *

Further reading

* Peter Ryhiner, ''Vita venerabilis theologi Samuelis Werenfelsii'' (1741)Google Books

External links

WorldCat page

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Werenfels, Samuel 1657 births 1740 deaths People from Basel-Stadt Swiss Calvinist and Reformed theologians 17th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 18th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 17th-century Swiss writers