Samuel Hearne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Hearne (February 1745 – November 1792) was an English explorer, fur-trader, author, and naturalist. He was the first European to make an overland excursion across northern Canada to the Arctic Ocean, actually

The English on Hudson Bay had long known that the First Nations to the northwest used native copper, as indicated by such words as

The English on Hudson Bay had long known that the First Nations to the northwest used native copper, as indicated by such words as

On 1 July 1767 he chiselled his name on smooth, glaciated stone at Sloop's Cove near Fort Prince of Wales where it remains today.

One of Wales's pupils, the poet

On 1 July 1767 he chiselled his name on smooth, glaciated stone at Sloop's Cove near Fort Prince of Wales where it remains today.

One of Wales's pupils, the poet

A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean

'' Edited by Joseph Tyrell. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1912. *

Coronation Gulf

Coronation Gulf lies between Victoria Island and mainland Nunavut in Canada. To the northwest it connects with Dolphin and Union Strait and thence the Beaufort Sea and Arctic Ocean; to the northeast it connects with Dease Strait and thence Queen ...

, via the Coppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave and Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake, and flows generally north to Coronation Gul ...

. In 1774, Hearne built Cumberland House

Cumberland House was a mansion on the south side of Pall Mall in London, England. It was built in the 1760s by Matthew Brettingham for Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany and was originally called York House. The Duke of York died in 176 ...

for the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

, its second interior trading post after Henley House

Henley House was the first inland post established by the Hudson's Bay Company, and is located in what is today Kenora District, Ontario, Canada. It was strategically situated west of James Bay about up the east-flowing Albany River at the mouth o ...

and the first permanent settlement in present Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

.

Biography

Samuel Hearne was born in February 1745 in London. Hearne's father was Secretary of the Waterworks ofLondon Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It re ...

, who died in 1748. His mother's name was Diana, and his sister's name was Sarah, three years younger than Samuel. Samuel Hearne joined the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

in 1756 at the age of 11 as midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

under the fighting captain Samuel Hood. He remained with Hood during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, seeing considerable action during the conflict, including the bombardment of Le Havre. At the end of the Seven Years' War, having served in the English Channel and then the Mediterranean, he left the Navy in 1763.

In February 1766, he joined the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

as a mate on the sloop ''Churchill'', which was then engaged in the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

trade out of Prince of Wales Fort, Churchill, Manitoba

Churchill is a town in northern Manitoba, Canada, on the west shore of Hudson Bay, roughly from the Manitoba–Nunavut border. It is most famous for the many polar bears that move toward the shore from inland in the autumn, leading to the nickname ...

. Two years later he became mate on the Brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

''Charlotte'' and participated in the company's short-lived black whale fishery. In 1767, he found the remains of James Knight's expedition. In 1768, he examined portions of the Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

coasts with a view to improving the cod fishery. During this time he gained a reputation for snowshoeing

Snowshoes are specialized outdoor gear for walking over snow. Their large footprint spreads the user's weight out and allows them to travel largely on top of rather than through snow. Adjustable bindings attach them to appropriate winter footwe ...

.

Hearne was able to improve his navigational skills by observing William Wales who was at Hudson Bay during 1768–1769 after being commissioned by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

to observe the Transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

with Joseph Dymond.

Exploration

The English on Hudson Bay had long known that the First Nations to the northwest used native copper, as indicated by such words as

The English on Hudson Bay had long known that the First Nations to the northwest used native copper, as indicated by such words as Yellowknife

Yellowknife (; Dogrib: ) is the capital, largest community, and only city in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, about south of the Arctic Circle, on the west side of Yellowknife Bay near the ...

. When, in 1768, a northern First Nation (some say it was Matonabbee) brought lumps of copper to Churchill, the governor, Moses Norton, decided to send Hearne in search of a possible copper mine. The basic theme of Hearne's three journeys is the Englishmen's ignorance of the methods of travel through this very difficult country and their dependence on First Nations who knew the land and how to live off of it.

''First Journey:'' Since there was no canoe route to the northwest, the plan was to go on foot over the frozen winter ground. Without canoes, they would have to carry as much food as possible and then live off the land. Hearne planned to join a group of northern First Nations that had come to trade at Churchill and somehow induce them to lead him to the copper mine. He left Churchill on 6 November 1769 along with two company employees, two Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree o ...

hunters and a band of Chipewyans and went north across the Seal River, an east–west river north of Churchill. By 19 November their European provisions gave out and their hunters had found little game (Hearne had left too late in the season and the caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

had already left the Barren Grounds for the shelter of the forested country further south). They headed west and north, finding only a few ptarmigan

''Lagopus'' is a small genus of birds in the grouse subfamily commonly known as ptarmigans (). The genus contains three living species with numerous described subspecies, all living in tundra or cold upland areas.

Taxonomy and etymology

The ge ...

, fish and three stray caribou. The Indigenous people, who knew the country, had better sense than to risk starvation in this way and began deserting. When the last First Nations left, Hearne and his European companions returned to the sheltered valley of the Seal River, where he was able to find venison, and reached Churchill on 11 December.

''Second Journey:'' Since he could not control the northern First Nations, Hearne proposed to try again using 'home guards', that is, Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree o ...

who lived around the post and hunted in exchange for European supplies. He left Churchill on 23 February. Reaching the Seal River, he found good hunting and followed it west until he reached a large lake, probably Sethnanei Lake. Here he decided to wait for better weather and live by fishing. In April the fish began to give out. On 24 April a large body of Indigenous people, mostly women, arrived from the south for the annual goose hunt. On 19 May the geese arrived and there was now plenty to eat. They headed north and east past Baralzone Lake. By June the geese had flown further north and they were again threatened with famine. At one point they killed three muskoxen and had to eat them raw because it was too wet to light a fire. They crossed the Kazan River above Yathkyed Lake where they found good hunting and fishing and then went west to Lake Dubawnt which is about northwest of Churchill. On 14 August his quadrant was destroyed, which accounts for the inaccuracy of latitudes on the remainder to this and the next journey. At this point the sources become vague, but Hearne returned to Churchill in the autumn. On his return journey he met Matonabbee who was to be his guide on the next journey. Matonabbee may well have saved him from freezing or starving to death. Most of the land Hearne crossed on his second journey is very desolate and was not properly explored again until Joseph Tyrrell in 1893.

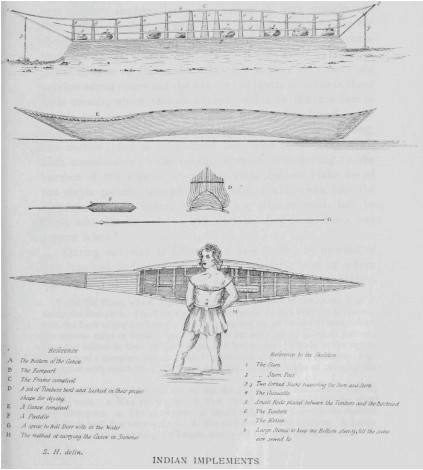

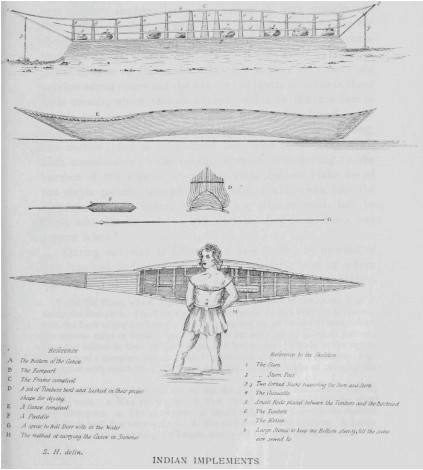

''Third Journey:'' Hearne contrived to travel as the only European with a group of Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified ...

guides led by Matonabbee. The group also included eight of Matonabbee's wives to act as beasts of burden in the sledge traces, camp servants, and cooks. This third expedition set out in December 1770, to reach the Coppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave and Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake, and flows generally north to Coronation Gul ...

in summer, by which he could descend to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

in canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the ter ...

s.

Matonabbee kept a fast pace, so fast they reached the great caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

traverse before provisions dwindled and in time for the spring hunt. Here Northern First Nations (Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

) hunters gathered to hunt the vast herds of caribou migrating north for the summer. A store of meat was laid up for Hearne's voyage and a band of "Yellowknife

Yellowknife (; Dogrib: ) is the capital, largest community, and only city in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, about south of the Arctic Circle, on the west side of Yellowknife Bay near the ...

" Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

joined the expedition. Matonabbee ordered his women to wait for his return in the Athabasca country to the west.

The Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

were generally a mild and peaceful people, however, they were in a state of conflict with the Inuit. A great number of Yellowknife First Nations joined Hearne's party to accompany them to the Copper-mine River with intent to kill Inuit, who were understood to frequent that river in considerable numbers.

On 14 July 1771, they reached the Copper-mine River, a small stream flowing over a rocky bed in the "Barren Lands of the Little Sticks". A few miles down the river, just above a cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble ...

, were the domed wigwam

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup' ...

s of an Eskimo

Eskimo () is an exonym used to refer to two closely related Indigenous peoples: the Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Greenlandic Inuit, and the Canadian Inuit) and the Yupik (or Yuit) of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related ...

camp. At 1 am on 17 July 1771 Matonabbee and the other Indigenous peoples fell upon the sleeping "Esquimaux" in a ruthless massacre. Approximately twenty men, women, and children were killed; this would be known as the Massacre at Bloody Falls.

... a young girl, seemingly about eighteen years of age, askilled so near me, that when the first spear was stuck into her side she fell down at my feet, and twisted round my legs, so that it was with difficulty that I could disengage myself from her dying grasps. As two Indian men pursued this unfortunate victim, I solicited very hard for her life; but the murderers made no reply till they had stuck both their spears through her body ... even at this hour I cannot reflect on the transactions of that horrid day without shedding tears.A few days later Hearne was the first European to reach the shore of the Arctic Ocean by an overland route. By tracing the Coppermine River to the Arctic Ocean he had established there was no

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

through the continent at lower latitudes.

This expedition also proved successful in its primary goal by discovering copper in the Coppermine River basin; however, an intensive search of the area yielded only one four-pound lump of copper and commercial mining was not considered viable.

Matonabbee led Hearne back to Churchill by a wide westward circle past Bear Lake in Athabasca Country. In midwinter he became the first European to see and cross Great Slave Lake

Great Slave Lake (french: Grand lac des Esclaves), known traditionally as Tıdeè in Tłı̨chǫ Yatıì (Dogrib), Tinde’e in Wıìlıìdeh Yatii / Tetsǫ́t’ıné Yatıé (Dogrib / Chipewyan), Tu Nedhé in Dëne Sųłıné Yatıé (Chi ...

. Hearne returned to Fort Prince of Wales on 30 June 1772 having walked some and explored more than .

Later life

Hearne was sent toSaskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

to establish Cumberland House

Cumberland House was a mansion on the south side of Pall Mall in London, England. It was built in the 1760s by Matthew Brettingham for Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany and was originally called York House. The Duke of York died in 176 ...

, the second inland trading post for the Hudson's Bay Company in 1774 (the first being Henley House

Henley House was the first inland post established by the Hudson's Bay Company, and is located in what is today Kenora District, Ontario, Canada. It was strategically situated west of James Bay about up the east-flowing Albany River at the mouth o ...

, established in 1743, up the Albany River

Albany, derived from the Gaelic for Scotland, most commonly refers to:

*Albany, New York, the capital of the State of New York and largest city of this name

* Albany, Western Australia, port city in the Great Southern

Albany may also refer to ...

). Having learned to live off the land, he took minimal provisions for the eight Europeans and two Home Guard Crees who accompanied him.

After consulting some local chiefs, Hearne chose a strategic site on Pine Island Lake in the Saskatchewan River

The Saskatchewan River (Cree: ''kisiskāciwani-sīpiy'', "swift flowing river") is a major river in Canada. It stretches about from where it is formed by the joining together of the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers to Lake Winn ...

, above Fort Paskoya. The site was linked to both the Saskatchewan River trade route and the Churchill system.

He became governor of Fort Prince of Wales on 22 January 1776. On 8 August 1782 Hearne and his complement of 38 civilians were confronted by a French force under the comte de La Pérouse composed of three ships, including one of 74 guns, and 290 soldiers. As a veteran Hearne recognised hopeless odds and surrendered without a shot. Hearne and some of the other prisoners were allowed to sail back to England from Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

in a small sloop.

Hearne returned the next year but found trade had deteriorated. The First Nations population had been decimated by European introduced diseases such as measles and smallpox, as well as starvation due to the lack of normal hunting supplies of powder and shot. Matonabbee had committed suicide and the rest of Churchill's leading First Nations had moved to other posts. Hearne's health began to fail and he delivered up command at Churchill on 16 August 1787 and returned to England.

In the last decade of his life he used his experiences on the barrens, on the northern coast, and in the interior to help naturalists like Thomas Pennant

Thomas Pennant (14 June OS 172616 December 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family estate, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire, in Wales.

As a naturalist he had ...

in their researches. His friend William Wales was a teacher at Christ's Hospital and he assisted Hearne to write ''A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean''. This was published in 1795, three years after Hearne's death of dropsy

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

in November 1792 at the age of 47.

Legacy

On 1 July 1767 he chiselled his name on smooth, glaciated stone at Sloop's Cove near Fort Prince of Wales where it remains today.

One of Wales's pupils, the poet

On 1 July 1767 he chiselled his name on smooth, glaciated stone at Sloop's Cove near Fort Prince of Wales where it remains today.

One of Wales's pupils, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

, made a brief notebook

A notebook (also known as a notepad, writing pad, drawing pad, or legal pad) is a book or stack of paper pages that are often ruled and used for purposes such as note-taking, journaling or other writing, drawing, or scrapbooking.

History

...

entry where he mentioned Hearne's book. Hearne may have been one of the inspirations for the ''Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of ''Lyrical Ballad ...

''.

Hearne's journals and maps were proven correct by Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

when he verified the discovery of the massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

at Bloody Falls during his own Coppermine Expedition of 1819-1822. He wrote: Several human skulls which bore the marks of violence, and many bones were strewed about the encampment, and as the spot exactly answers the description, given by Mr Hearne, of the place...Hearne is mentioned by

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

in the sixth chapter of '' The Origin of Species'':

In North America the black bear was seen by Hearne swimming for hours with widely open mouth, thus catching, like a whale, insects in the water.Samuel Hearne's account of his exploration of the north, ''A Journey from Prince of Wales' Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean'', originally published in 1795, was edited by Joseph Tyrell and reprinted as part of the General Series of the Champlain Society. There is a Junior/Senior High School that was built and named after him in

Inuvik

Inuvik (''place of man'') is the only town in the Inuvik Region, and the third largest community in Canada's Northwest Territories. Located in what is sometimes called the Beaufort Delta Region, it serves as its administrative and service ce ...

, Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

. A school in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

, Ontario was also built in his name in 1973.

References

*Further reading

* ''A Journey to the Northern Ocean: The Adventures of Samuel Hearne'' by Samuel Hearne. Foreword by Ken McGoogan. Published by TouchWood Editions, 2007. * ''Ancient Mariner: The Arctic Adventures of Samuel Hearne, the Sailor Who Inspired Coleridge's Masterpiece'' by Ken McGoogan. Published by Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004. * ''Coppermine Journey: An Account of Great Adventure Selected from the Journals of Samuel Hearne'' by Farley Mowat. Published by McClelland & Stewart, 1958. * ''Samuel Hearne and the North West Passage'' by Gordon Speck. Published by Caxton Printers, Ltd, 1963. * ''Northern Wilderness'' by Ray Mears. Published by Hodder & Stoughton, 2009, Chapters 4–6. * Hearne, Samuel.A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean

'' Edited by Joseph Tyrell. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1912. *

External links

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hearne, Samuel 1745 births 1792 deaths Deaths from edema English explorers of North America Explorers of Canada Hudson's Bay Company people Military personnel from London Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Pre-Confederation Saskatchewan people