SMS Alexandrine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was a member of the of steam corvettes built for the German (Imperial Navy) in the 1880s. Intended for service in the German colonial empire, the ship was designed with a combination of steam and sail power for extended range, and was equipped with a

By this time, the situation in Samoa had calmed, so was sent on a tour of German protectorates in

By this time, the situation in Samoa had calmed, so was sent on a tour of German protectorates in

battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

of ten guns. was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at the (Imperial Shipyard) in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

in 1882, she was launched in February 1885, and she was completed in October 1886 before being laid up after completing sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

.

was first activated in 1889 for a deployment to the Central Pacific, where competing claims to the islands of Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

created tension between several colonial powers. The ship patrolled Deutsch-Neuguinea, Germany's colonial holdings in the Central Pacific, until 1891, when she joined the German Cruiser Squadron, which was sent to Chile to protect German nationals during the Chilean Civil War of 1891

The Chilean Civil War of 1891 (also known as Revolution of 1891) was a civil war in Chile fought between forces supporting Congress and forces supporting the President, José Manuel Balmaceda from 16 January 1891 to 18 September 1891. The war ...

. The squadron thereafter cruised off East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

in 1892, and by the end of the year, went to German East Africa. In 1893, she was sent to Brazil where the (Revolt of the Fleet) in that country threatened German interests. The ships were then sent back to East Asia to monitor the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

of 1894–1895.

In March 1895, was recalled to Germany; while en route, she stopped in Morocco to pressure local authorities into paying reparations for the murder of two German citizens. On her arrival in Germany she was found to be in poor condition after several years abroad, and so she was decommissioned in June 1895. She served as a floating battery

A floating battery is a kind of armed watercraft, often improvised or experimental, which carries heavy armament but has few other qualities as a warship.

History

Use of timber rafts loaded with cannon by Danish defenders of Copenhagen a ...

in Danzig from 1904 to 1907, when she was stricken from the naval register

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval autho ...

, sold and used temporarily as a floating workshop, and then broken up

Ship-breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships for either a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sold for re-use, ...

later in 1907.

Design

The six ships of the class were ordered in the late 1870s to supplement Germany's fleet of cruising warships, which at that time relied on several ships that were twenty years old. and her sister ships were intended to patrol Germany's colonial empire and safeguard German economic interests around the world. The last two ships to be built, and , were built to a slightly larger design, being slightly longer and slightly heavier than their sisters. waslong overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

, with a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of forward. She displaced at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship's crew consisted of 25 officers and 257 enlisted men. She was powered by two marine steam engine

A marine steam engine is a steam engine that is used to power a ship or boat. This article deals mainly with marine steam engines of the reciprocating type, which were in use from the inception of the steamboat in the early 19th century to their ...

s that drove two 2-bladed screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s, with steam provided by eight coal-fired fire-tube boilers, which gave her a top speed of at . She had a cruising radius of at a speed of . was equipped with a three-masted barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

rig to supplement her steam engines on extended overseas deployments.

was armed with a battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

of ten 22- caliber (cal.) breech-loading guns and two 24-cal. guns. She also carried six Hotchkiss revolver cannon. Later in her career, the 15 cm guns were replaced with more modern 30-cal. versions, and the 8.7 cm guns were replaced with four SK L/35 guns.

Service history

, ordered under the contract name "G", waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in February 1882 at the (Imperial Shipyard) in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, and her completed hull was launched on 7 February 1885. Then-prince Wilhelm

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Mount ...

, the grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm I

William I or Wilhelm I (german: Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig; 22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888) was King of Prussia from 2 January 1861 and German Emperor from 18 January 1871 until his death in 1888. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he was the ...

, gave the christening speech at her launching. The completed ship began sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

in October 1886; these lasted until January 1887, when the ship was decommissioned in Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

. At the time, General Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprara de Montecuccoli (English: ''Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprara, and Montecuccoli''; born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman who served as the cha ...

, the head of the Imperial Admiralty, had implemented a plan whereby Germany's colonies would be protected by gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

s, while larger warships would generally be kept in reserve, with a handful assigned to a flying squadron that could respond to crises quickly.

Deployment abroad

1889–1891

The ship remained laid up until 1889, when a major cyclone struck the islands ofSamoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

on 16 March and destroyed two German warships in Apia

Apia () is the capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

...

—the gunboats and . Conflicting claims on the islands from other powers led the German government to activate to defend German interests there. She was joined in that task by her sister ship and the gunboat , which had been in East African and East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

n waters, respectively. left Wilhelmshaven on 15 April, with now-Kaiser Wilhelm II aboard and steamed to Wangerooge

Wangerooge is one of the 32 Frisian Islands in the North Sea located close to the coasts of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. It is also a municipality in the district of Friesland in Lower Saxony in Germany.

Wangerooge is one of the East F ...

, where Wilhelm II disembarked. The ship, using a combination of steam and sail power, proceeded through the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, stopping in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

along the way, before entering the Suez Canal at Port Said. She then continued through the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and stopped in Aden before crossing the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

to Albany, Australia; from there, she went to Sydney, arriving there on 6 July.

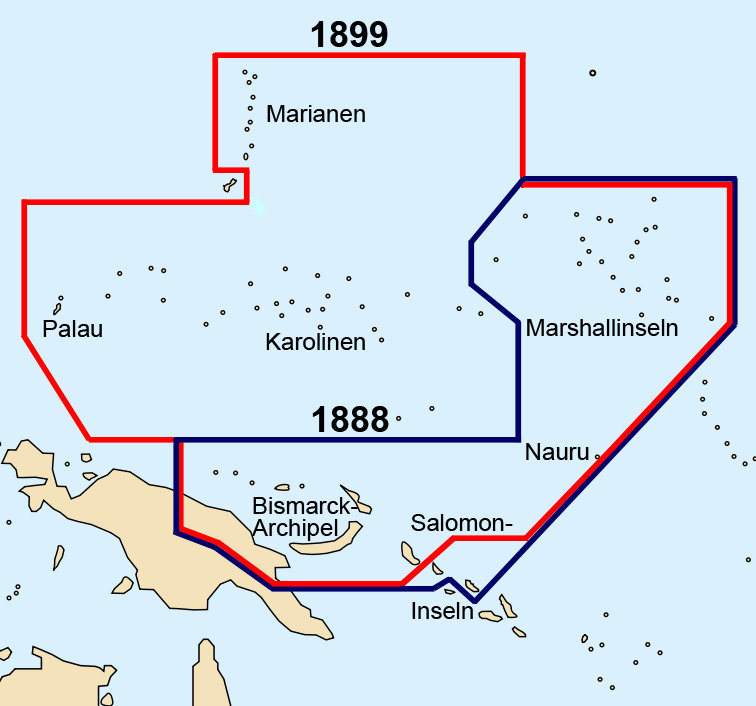

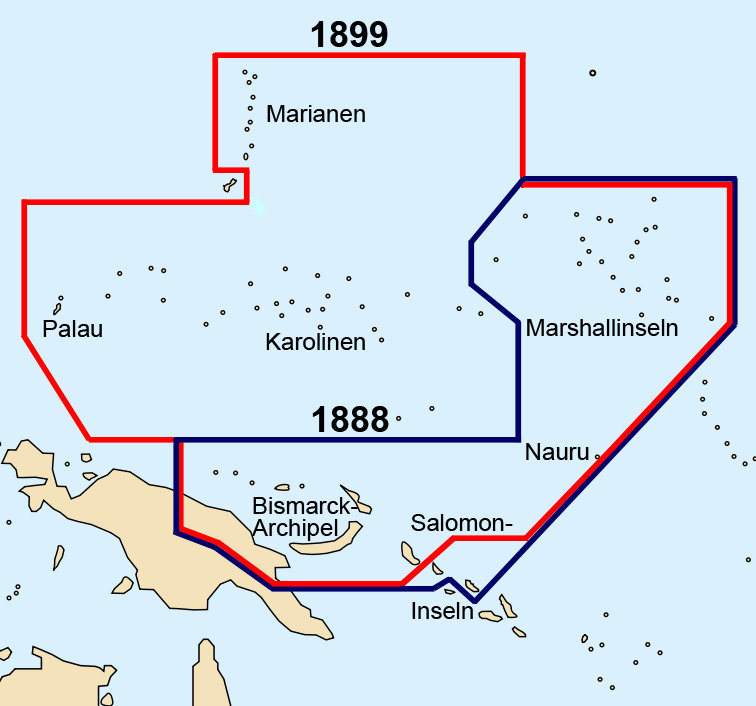

By this time, the situation in Samoa had calmed, so was sent on a tour of German protectorates in

By this time, the situation in Samoa had calmed, so was sent on a tour of German protectorates in Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

, beginning on 24 July. Stops included the North Solomon Islands

The Northern Solomons were the more northerly group of islands in the Solomon Islands (archipelago) over which Germany declared a protectorate in 1885. Initially, the German Solomon Islands Protectorate included, in the south-east, Choiseu ...

, Matupi in Neu-Pommern

New Britain ( tpi, Niu Briten) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi the Da ...

, Finschhafen

Finschhafen is a town east of Lae on the Huon Peninsula in Morobe Province of Papua New Guinea. The town is commonly misspelt as Finschafen or Finschaven. During World War II, the town was also referred to as Fitch Haven in the logs of some U.S ...

in Deutsch-Neuguinea, and the Hermit Islands

The Hermit Islands are a group of 17 islands within the Western Islands of the Bismarck Archipelago, Papua New Guinea. Their coordinates are .

History

The first sighting by Europeans of Hermit islands was by the Spanish navigator Iñigo Órti ...

. The trip culminated with Kapsu island off Neu-Mecklenburg, where sent a landing party ashore to punish local residents who had murdered a pair of German citizens. From there, sailed to Sydney, where she remained from 1 to 30 November for repairs and to rest the crew. In March 1890, a steamer arrived in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

, New Zealand, with a new crew to relieve the men aboard . The ship then went to Apia, where she remained until early May, when she was sent on a tour of the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

with the local (Imperial Commissioner) on board. While en route, she stopped in the Gilbert Islands to settle disputes between Germans and locals. In June, the ship's crew participated in the ceremony installing Malietoa Laupepa

Susuga Malietoa Laupepa (1841 – 22 August 1898) was the ruler (Malietoa) of Samoa in the late 19th century.

Personal life

Laupepa was born in 1841 in Sapapali'i, Savai'i, Samoa. His father was Malietoa Mōli and mother was Fa’alaitaua Fua ...

as the ruler of Samoa.

then sailed to Sydney for maintenance, where in July she learned she had been assigned to the Cruiser Squadron under (''KAdm''—Rear Admiral) Victor Valois. After visiting Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

and Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, joined the other two corvettes of squadron—the flagship , and —in Apia on 16 September. On 6 January 1891, visited several islands in the Samoa group before continuing with the rest of the squadron for a cruise in East Asian waters. While in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, China in April, exchanged crews another time. In the meantime, the Chilean Civil War of 1891

The Chilean Civil War of 1891 (also known as Revolution of 1891) was a civil war in Chile fought between forces supporting Congress and forces supporting the President, José Manuel Balmaceda from 16 January 1891 to 18 September 1891. The war ...

had broken out, prompting the German high command to send Valois's ships there on 3 May to safeguard German nationals in the country. While on the way, ran low on coal and had to be towed for much of the journey. The ships arrived off the coast of Chile on 9 July and Valois secured an agreement with the authorities in Valparaiso for landing parties from the vessels to secure the European quarter of the city.

1891–1895

With the war over, the Cruiser Squadron left Chile in December and transited the Strait of Magellan into theSouth Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

. They stopped in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, where ''KAdm'' Friedrich von Pawelsz took command of the squadron on 23 February 1892. The three corvettes steamed to German East Africa, where was detached; and continued on to East Asia. While in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

, received another new crew, and she took replacements for men from the gunboats and aboard as well. then returned to Chinese waters and stopped in Chemulpo

Incheon (; ; or Inch'ŏn; literally "kind river"), formerly Jemulpo or Chemulp'o (제물포) until the period after 1910, officially the Incheon Metropolitan City (인천광역시, 仁川廣域市), is a city located in northwestern South Kore ...

, Korea, where the ship's captain received an audience with Gojong, the King of Joseon

The Joseon dynasty ruled Korea, succeeding the 400-year-old Goryeo dynasty in 1392 through the Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese annexation in 1910. Twenty-seven monarchs ruled over united Korea for more than 500 years.

List of monarchs

See ...

. While cruising in the Bohai Sea

The Bohai Sea () is a marginal sea approximately in area on the east coast of Mainland China. It is the northwestern and innermost extension of the Yellow Sea, to which it connects to the east via the Bohai Strait. It has a mean depth of ...

, several of the ship's crewmen fell seriously ill, forcing to put into Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, Japan, where the German government operated a hospital.

The ship remained in Yokohama until 23 October, when she left to rendezvous with the flagship , in Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

. After arriving there on 4 November, the two ships proceeded to East Africa, where unrest due to a feared succession crisis on the island of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

. Following the death of Sultan Ali bin Said of Zanzibar

Sayyid Ali bin Said al-Busaidi, GCSI, (1854 – March 5, 1893) ( ar, علي بن سعيد البوسعيد) was the fourth Sultan of Zanzibar. He ruled Zanzibar from February 13, 1890, to March 5, 1893. In June 1890 he was forced to accept ...

in March 1893, power passed peacefully to his nephew, Hamad bin Thuwaini

Sayyid Hamad bin Thuwaini Al-Busaid ( ar, حمد بن ثويني البوسعيد) ( – ) was the fifth Sultan of Zanzibar. He ruled Zanzibar from 5 March 1893 to 25 August 1896.

Life

Sayyid Hamad bin Thuwaini Al-Busaid was born on 1857, probably ...

, and the crisis was averted. As a result, and were instead diverted to Cape Town, where on 6 April the Cruiser Squadron was disbanded. Both ships entered the dry dock in Cape Town for overhauls, after which they were sent to South America on 20 May. By mid-June, they had reached Brazil, and thereafter made stops in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Argentina and Montevideo, Uruguay. The outbreak of the Revolta da Armada

The Brazilian Naval Revolts, or the Revoltas da Armada (in Portuguese), were armed mutinies promoted mainly by admirals Custódio José de Melo and Saldanha da Gama and their fleet of rebel Brazilian navy ships against the claimed unconstitu ...

in Brazil forced both ships to return to the country to protect German interests there. The two corvettes were tasked with protecting guarding German-flagged merchant vessels and protecting German nationals in Brazil.

While operating in Brazil, an outbreak of Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

aboard forced her to go into a quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

in the Montevideo roadstead. The Brazilian government suppressed the revolution in early 1894, and by that time, s sister had joined the German ships in Brazil. Tensions between China and Japan had been rising steadily over control of Korea, and as a result, the German high command sent the three corvettes to East Asia. On 7 March, they rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

and entered the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

, but while en route, the ships were diverted to Peru on 13 July to protect German interests during a revolution in the country. A week later, First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

broke out, and Germany formed the East Asia Division with the three corvettes. On 15 August, the situation in Peru had calmed enough to allow the division to return to its intended mission in East Asia. They arrived in Yokohama, Japan on 26 September, and proceeded to Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

for maintenance. After completing repairs, steamed to the northern coast of China to protect German interests in the region.

Fate

The ship's assignment to the East Asia Division did not last long; on 2 March 1895, she received orders to return to Germany. She leftSingapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

on 22 March, marking her departure from the East Asia Division. While in Port Said, she was ordered to go to Morocco to lend weight to German negotiators seeking compensation for the murder of two Germans in the country. After completing the task, she continued on to Wilhelmshaven, arriving there on 25 May. She was decommissioned a week later on 1 June; upon examination, it was found that her hull had badly deteriorated, and she was unsuitable for any further use. was towed to Danzig, where she was decommissioned. From 3 May 1904, she was employed as a floating battery

A floating battery is a kind of armed watercraft, often improvised or experimental, which carries heavy armament but has few other qualities as a warship.

History

Use of timber rafts loaded with cannon by Danish defenders of Copenhagen a ...

, and on 27 May 1907, she was stricken from the naval register

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval autho ...

and sold for 148,000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

. The buyer briefly used the ship as a floating workshop before breaking her up later that year.

Notes

References

* * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexandrine Carola-class corvettes 1885 ships Ships built in Kiel