Russian–American Telegraph on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Russian–American Telegraph, also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland Telegraph, was an attempt by the

The Russian–American Telegraph, also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland Telegraph, was an attempt by the

By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world.

Working to meet that challenge were two telegraph pioneers, one,

By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world.

Working to meet that challenge were two telegraph pioneers, one,

The Russian–American Telegraph, also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland Telegraph, was an attempt by the

The Russian–American Telegraph, also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland Telegraph, was an attempt by the Western Union Telegraph Company

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

from 1865 to 1867 to lay a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

line from San Francisco, California

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, to Moscow, Russia

Moscow ( , American English, US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia. The city stands on t ...

.

The route of the $3,000,000 undertaking (equivalent to $ today) was intended to travel from California via Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Washington Territory, the Colony of British Columbia The Colony of British Columbia refers to one of two colonies of British North America, located on the Pacific coast of modern-day Canada:

*Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)

*Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871)

See also

*History of Br ...

and Russian America, under the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Ameri ...

and cross the broad breadth of the Eurasian Continent to Moscow, where lines would communicate with the rest of Europe. It was proposed as a much longer alternative to the challenge of long, deep underwater cables in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

, having only to cross the comparatively narrow Bering Strait underwater between North America and Siberia.

Laying the cable across Siberia proved more difficult than expected. Meanwhile, Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field (November 30, 1819July 12, 1892) was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.

Early ...

's transatlantic cable was successfully completed, leading to the abandonment in 1867 of the trans-Russian effort. A Government of Canada historic plaque adds these specifics:

"In 1867 ... construction ceased at Fort Stager at the confluence of the Kispyap and Skeena rivers. The section from New Westminster to the Cariboo was bought by the Canadian Government in 1880."

In spite of the project's economic failure, many regard aspects of the effort a success on the weight of various benefits the exploration brought to the regions that were traversed. To date, no entities have attempted a communications cable across the Bering Sea, with all extant submarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables laid beginning in the 1850s carried tel ...

s that travel westbound from North America following more southerly routes across much longer stretches of the North Pacific Ocean, connecting to Asia in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and then on to the Asian mainland.

Rival plans

By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world.

Working to meet that challenge were two telegraph pioneers, one,

By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world.

Working to meet that challenge were two telegraph pioneers, one, Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field (November 30, 1819July 12, 1892) was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.

Early ...

, seeking to lay an undersea telegraph cable west to east across the Atlantic from North America, and the other, Perry Collins Perry McDonough Collins (1813–1900)

timeline at frontiers.loc.govCorday Mackay

Bering Strait and Sibera to Moscow. Field's

timeline at frontiers.loc.govCorday Mackay

Bering Strait and Sibera to Moscow. Field's

Atlantic Telegraph Company

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was a company formed on 6 November 1856 to undertake and exploit a commercial telegraph cable across the Atlantic ocean, the first such telecommunications link.

History

Cyrus Field, American businessman and finan ...

laid the first transatlantic cable across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in 1858. However, it had broken three weeks afterwards and attempts to repair it had been unsuccessful.

Meanwhile, entrepreneur Perry Collins Perry McDonough Collins (1813–1900)

timeline at frontiers.loc.govCorday Mackay

Hiram Sibley, head of the

On July 1, 1864, the American president

On July 1, 1864, the American president  The Colony of British Columbia gave the project its full and enthusiastic support, allowing the materials for the line to be brought in free of duties and tolls. Chosen as the British Columbia terminus, New Westminster gloated over its triumph over its rival, Victoria, and it was predicted in the ''British Columbian'' newspaper that "New Westminster, traduced and dreaded by its jealous neighbor, will now be at the centre of all these great systems." The right of way for the telegraph line followed the shoreline west from the US border, then traversed the high ground of what is now White Rock and South Surrey to the Nicomekl River. From Mud Bay the telegraph line followed the Kennedy Trail northwest across Surrey and North Delta to the Fraser River.

At Brownsville, a cable was laid across the river to New Westminster. The surveying in British Columbia had started before the line reached New Westminster on March 21, 1865. Edward Conway had walked to

The Colony of British Columbia gave the project its full and enthusiastic support, allowing the materials for the line to be brought in free of duties and tolls. Chosen as the British Columbia terminus, New Westminster gloated over its triumph over its rival, Victoria, and it was predicted in the ''British Columbian'' newspaper that "New Westminster, traduced and dreaded by its jealous neighbor, will now be at the centre of all these great systems." The right of way for the telegraph line followed the shoreline west from the US border, then traversed the high ground of what is now White Rock and South Surrey to the Nicomekl River. From Mud Bay the telegraph line followed the Kennedy Trail northwest across Surrey and North Delta to the Fraser River.

At Brownsville, a cable was laid across the river to New Westminster. The surveying in British Columbia had started before the line reached New Westminster on March 21, 1865. Edward Conway had walked to

Work began in Russian America, in 1865 but initially, little progress was made. Contributing to this lack of success was the climate, the terrain, supply shortages and the late arrival of the construction teams. Nevertheless, the entire route through Russian America was surveyed by the fall of 1866. Rather than waiting until spring, as was the usual practice, construction began and continued through that winter.

Many of the Western Union workers were unaccustomed to severe northern winters and working in frigid conditions made erecting the line a difficult experience. Fires had to be lit to thaw out the frozen ground before holes could be dug to place the telegraph poles. For transportation and to haul the supplies, the only option the work crews had was to use teams of

Work began in Russian America, in 1865 but initially, little progress was made. Contributing to this lack of success was the climate, the terrain, supply shortages and the late arrival of the construction teams. Nevertheless, the entire route through Russian America was surveyed by the fall of 1866. Rather than waiting until spring, as was the usual practice, construction began and continued through that winter.

Many of the Western Union workers were unaccustomed to severe northern winters and working in frigid conditions made erecting the line a difficult experience. Fires had to be lit to thaw out the frozen ground before holes could be dug to place the telegraph poles. For transportation and to haul the supplies, the only option the work crews had was to use teams of

When that section of the line reached New Westminster, British Columbia, in the spring of 1865, the first message it carried was of the April 15

When that section of the line reached New Westminster, British Columbia, in the spring of 1865, the first message it carried was of the April 15  In 1866, the work progressed rapidly in that section, fifteen log telegraph cabins had been built and line had been strung from Quesnel, reaching the Kispiox and

In 1866, the work progressed rapidly in that section, fifteen log telegraph cabins had been built and line had been strung from Quesnel, reaching the Kispiox and  In addition, the expedition left behind a vast store of supplies that were put to good use by some of the First Nations inhabitants. Near Hazelton, Colonel Bulkley had been impressed by

In addition, the expedition left behind a vast store of supplies that were put to good use by some of the First Nations inhabitants. Near Hazelton, Colonel Bulkley had been impressed by  After the project was abandoned, the Hagwilgets at Hazelton built a second bridge from cable that the company had left behind. Both bridges were considered marvels of engineering and were credited as being "one of the romances of bridge building."

After the project was abandoned, the Hagwilgets at Hazelton built a second bridge from cable that the company had left behind. Both bridges were considered marvels of engineering and were credited as being "one of the romances of bridge building."

In the long run, the telegraph expedition, while an abject economic failure, provided a further means by which America was able to expand its

In the long run, the telegraph expedition, while an abject economic failure, provided a further means by which America was able to expand its

* Kennecott, Alaska and the Kennicott Glacier are named for the expedition's naturalist, Robert Kennicott. Although Kennicott died on the expedition, on May 13, 1866, his work was publicized by

* Kennecott, Alaska and the Kennicott Glacier are named for the expedition's naturalist, Robert Kennicott. Although Kennicott died on the expedition, on May 13, 1866, his work was publicized by

Finding Aid to Western Union Telegraph Expedition Collection, 1865–1867

{{DEFAULTSORT:Russian-American Telegraph History of California History of British Columbia History of Yukon Russian Empire–United States relations Russian America History of the telegraph History of telecommunications in the United States Telecommunications in Russia History of science and technology in Russia Military expeditions of the United States Pacific expeditions Telegraph companies Western Union 1865 establishments in the United States 19th century in technology

timeline at frontiers.loc.govCorday Mackay

Hiram Sibley, head of the

Western Union Telegraph Company

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

with the idea of an overland telegraph line that would run through the Northwestern states, the colony of British Columbia and Russian Alaska. Together, they worked on promoting the idea and obtained considerable support in the US, London and Russia.

Preparations

On July 1, 1864, the American president

On July 1, 1864, the American president Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

granted Western Union a right of way from San Francisco to the British Columbia border and assigned them the steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

''Saginaw'' from the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

.

The ''George S. Wright'' and the '' Nightingale'', a former slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

, were also put into service, as well as a fleet of riverboats and schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

s.

To supervise the construction, Collins chose Colonel Charles Bulkley, who had been the Superintendent of Military Telegraphs. Being an ex-military man, Bulkley divided the work crews into "working divisions" and an "Engineer Corps."

Edward Conway was made the head of the project's American route and British Columbia sections. Franklin Pope was assigned to Conway and given the responsibility for the exploring of British Columbia. The task of exploring Russian America went to the Smithsonian naturalist Robert Kennicott. In Siberia, the construction and exploration was under the charge of Russian nobleman Serge Abasa. Assigned to him were Collins Macrae, George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

, and J. A. Mahood.

Exploration and construction teams were divided into groups: one was in British Columbia, another worked around the Yukon River

The Yukon River (Gwichʼin language, Gwich'in: ''Ųųg Han'' or ''Yuk Han'', Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, Yup'ik: ''Kuigpak'', Inupiaq language, Inupiaq: ''Kuukpak'', Deg Xinag language, Deg Xinag: ''Yeqin'', Hän language, Hän: ''Tth'echù' ...

and Norton Sound with headquarters at St. Michael, Alaska

St. Michael ( esu, Taciq, ik, Tasiq; Taziq, russian: Сент-Майкл), historically referred to as Saint Michael, is a city in Nome Census Area, Alaska. The population was 401 at the 2010 census, up from 368 in 2000.

Geography

St. Michael ...

, a third explored the area along the Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

in Siberia, and a fourth group of about forty men was sent to Port Clarence

Port Clarence is a small village now within the borough of Stockton-on-Tees and ceremonial county of County Durham, England. It is situated on the north bank of the River Tees, and hosts the northern end of the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge.

...

to build the line that was to cross the Bering Strait to Siberia.

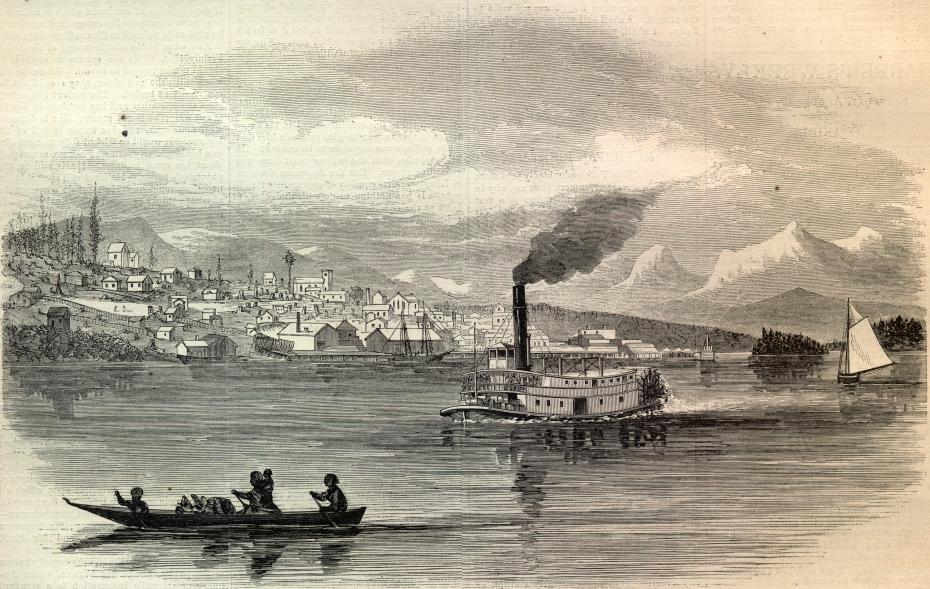

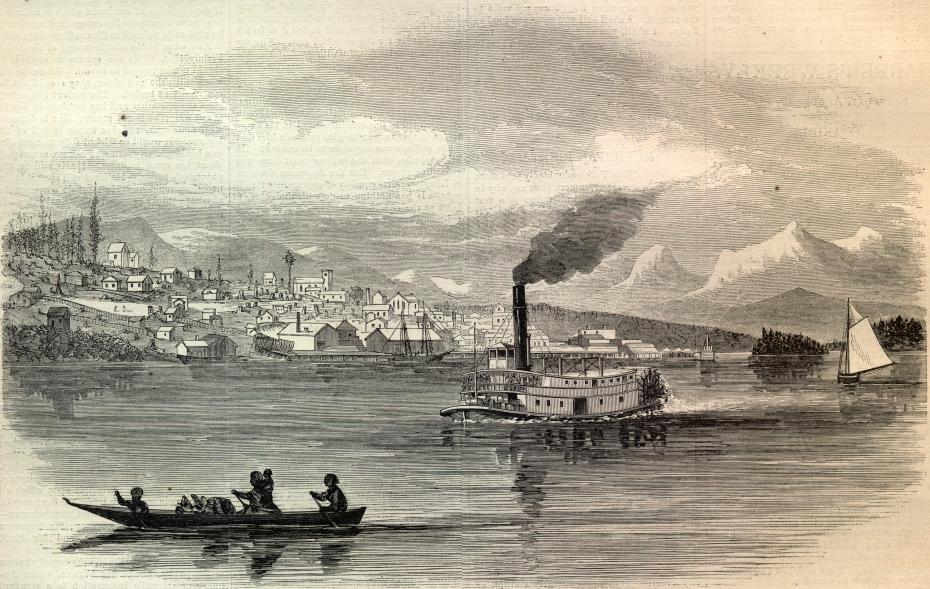

The Colony of British Columbia gave the project its full and enthusiastic support, allowing the materials for the line to be brought in free of duties and tolls. Chosen as the British Columbia terminus, New Westminster gloated over its triumph over its rival, Victoria, and it was predicted in the ''British Columbian'' newspaper that "New Westminster, traduced and dreaded by its jealous neighbor, will now be at the centre of all these great systems." The right of way for the telegraph line followed the shoreline west from the US border, then traversed the high ground of what is now White Rock and South Surrey to the Nicomekl River. From Mud Bay the telegraph line followed the Kennedy Trail northwest across Surrey and North Delta to the Fraser River.

At Brownsville, a cable was laid across the river to New Westminster. The surveying in British Columbia had started before the line reached New Westminster on March 21, 1865. Edward Conway had walked to

The Colony of British Columbia gave the project its full and enthusiastic support, allowing the materials for the line to be brought in free of duties and tolls. Chosen as the British Columbia terminus, New Westminster gloated over its triumph over its rival, Victoria, and it was predicted in the ''British Columbian'' newspaper that "New Westminster, traduced and dreaded by its jealous neighbor, will now be at the centre of all these great systems." The right of way for the telegraph line followed the shoreline west from the US border, then traversed the high ground of what is now White Rock and South Surrey to the Nicomekl River. From Mud Bay the telegraph line followed the Kennedy Trail northwest across Surrey and North Delta to the Fraser River.

At Brownsville, a cable was laid across the river to New Westminster. The surveying in British Columbia had started before the line reached New Westminster on March 21, 1865. Edward Conway had walked to Hope

Hope is an optimistic state of mind that is based on an expectation of positive outcomes with respect to events and circumstances in one's life or the world at large.

As a verb, its definitions include: "expect with confidence" and "to cherish ...

and was dismayed by the difficulty of the terrain. In response to Conway's concerns, the Colony of British Columbia agreed to build a road from New Westminster to Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

where it would meet the newly completed Cariboo Road

The Cariboo Road (also called the Cariboo Wagon Road, the Great North Road or the Queen's Highway) was a project initiated in 1860 by the Governor of the Colony of British Columbia, James Douglas. It involved a feat of engineering stretching fro ...

. The telegraph company's only responsibility would be to string wires along it.

Route through Russian America

Work began in Russian America, in 1865 but initially, little progress was made. Contributing to this lack of success was the climate, the terrain, supply shortages and the late arrival of the construction teams. Nevertheless, the entire route through Russian America was surveyed by the fall of 1866. Rather than waiting until spring, as was the usual practice, construction began and continued through that winter.

Many of the Western Union workers were unaccustomed to severe northern winters and working in frigid conditions made erecting the line a difficult experience. Fires had to be lit to thaw out the frozen ground before holes could be dug to place the telegraph poles. For transportation and to haul the supplies, the only option the work crews had was to use teams of

Work began in Russian America, in 1865 but initially, little progress was made. Contributing to this lack of success was the climate, the terrain, supply shortages and the late arrival of the construction teams. Nevertheless, the entire route through Russian America was surveyed by the fall of 1866. Rather than waiting until spring, as was the usual practice, construction began and continued through that winter.

Many of the Western Union workers were unaccustomed to severe northern winters and working in frigid conditions made erecting the line a difficult experience. Fires had to be lit to thaw out the frozen ground before holes could be dug to place the telegraph poles. For transportation and to haul the supplies, the only option the work crews had was to use teams of sled dogs

A sled dog is a dog trained and used to pull a land vehicle in harness, most commonly a sled over snow.

Sled dogs have been used in the Arctic for at least 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transportation in Arctic areas ...

.

When the Atlantic cable was successfully completed and the first transatlantic message to England was sent in July 1866, the men in the Russian American division were not aware of it until a full year later.

By then telegraph stations had been built, thousands of poles were cut and distributed along the route and over of line had been completed in Russian America. Despite the fact that so much progress had been made, in July 1867, the work was officially ceased.

Route through British Columbia

When that section of the line reached New Westminster, British Columbia, in the spring of 1865, the first message it carried was of the April 15

When that section of the line reached New Westminster, British Columbia, in the spring of 1865, the first message it carried was of the April 15 assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the hea ...

.

In May 1865 construction began from New Westminster to Yale and then along the Cariboo Road

The Cariboo Road (also called the Cariboo Wagon Road, the Great North Road or the Queen's Highway) was a project initiated in 1860 by the Governor of the Colony of British Columbia, James Douglas. It involved a feat of engineering stretching fro ...

and the Fraser River

The Fraser River is the longest river within British Columbia, Canada, rising at Fraser Pass near Blackrock Mountain in the Rocky Mountains and flowing for , into the Strait of Georgia just south of the City of Vancouver. The river's annual d ...

to Quesnel Quesnel or Quesnell means "little oak" in the Picard dialect of French. It is used as a proper name and may refer to:

Places

* Le Quesnel, a commune the Somme department in France

* Quesnel, British Columbia, a city in British Columbia, Canada ...

. Winter brought a halt to construction, but resumed in the spring with 150 men working northwest from Quesnel.

In 1866, the work progressed rapidly in that section, fifteen log telegraph cabins had been built and line had been strung from Quesnel, reaching the Kispiox and

In 1866, the work progressed rapidly in that section, fifteen log telegraph cabins had been built and line had been strung from Quesnel, reaching the Kispiox and Bulkley River

The Bulkley River in British Columbia is a major tributary of the Skeena River. The Bulkley is long with a drainage basin covering .

Much of the Bulkey is paralleled by Highway 16. It flows west from Bulkley Lake past Perow and is joined near ...

s. The company's sternwheeler, ''Mumford,'' traveled up the Skeena River from the Pacific Coast three times that season, successfully delivering of material for the telegraph line and 12,000 rations for its workers.

The line passed Fort Fraser and reached the Skeena River, creating the settlement of Hazelton when it was learned that Cyrus West Field had successfully laid the transatlantic cable on July 27.

In British Columbia, construction of the overland line was halted on February 27, 1867, as the whole project was now deemed obsolete.

Nevertheless, left behind in British Columbia was a usable telegraph system from New Westminster to Quesnel, which later would be run to the Cariboo Gold Rush town of Barkerville, and a trail that had been beat through what had largely been uncharted wilderness.

In addition, the expedition left behind a vast store of supplies that were put to good use by some of the First Nations inhabitants. Near Hazelton, Colonel Bulkley had been impressed by

In addition, the expedition left behind a vast store of supplies that were put to good use by some of the First Nations inhabitants. Near Hazelton, Colonel Bulkley had been impressed by the bridge The Bridge may refer to:

Art, entertainment and media Art

* ''The Bridge'' (sculpture), a 1997 sculpture in Atlanta, Georgia, US

* Die Brücke (''The Bridge''), a group of German expressionist artists

* ''The Bridge'' (M. C. Escher), a lithograph ...

the Hagwilget Hagwilget or Hagwilgyet is a First Nations reserve community of the Wet'suwet'en people located on the lower Bulkley River just east of Hazelton in northwestern British Columbia, Canada. The community's name means "well-dressed" as in "ostentat ...

s had built across the Bulkley River, but was reluctant to let his work party cross it until it had been reinforced with cable.

After the project was abandoned, the Hagwilgets at Hazelton built a second bridge from cable that the company had left behind. Both bridges were considered marvels of engineering and were credited as being "one of the romances of bridge building."

After the project was abandoned, the Hagwilgets at Hazelton built a second bridge from cable that the company had left behind. Both bridges were considered marvels of engineering and were credited as being "one of the romances of bridge building."

Legacy

In the long run, the telegraph expedition, while an abject economic failure, provided a further means by which America was able to expand its

In the long run, the telegraph expedition, while an abject economic failure, provided a further means by which America was able to expand its Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

beyond its national boundaries and may have precipitated the US purchase of Alaska. The expedition was responsible for the first examination of the flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

, fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

and geology of Russian America and the members of the telegraph project were able to play a crucial role in the purchase of Alaska by providing useful valuable data on the territory.

The Colony of British Columbia meanwhile could further explore, colonize and communicate with its northern landscapes beyond what had been done by the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

.

Many of the towns in Northwestern British Columbia can trace their initial European settlement back to the Collins Overland Telegraph. Some examples of these are Hazelton, Burns Lake

Burns Lake is a rural village in the North-western-Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada, incorporated in 1923. The village had a population of 1,779 as of the 2016 Census.

The village is known for its rich First Nations heritage, and ...

, Telkwa and Telegraph Creek

Telegraph Creek is a small community located off Highway 37 in northern British Columbia at the confluence of the Stikine River and Telegraph Creek. The only permanent settlement on the Stikine River, it is home to approximately 250 members of Tah ...

.

The expedition also laid a foundation for the construction of the Yukon Telegraph line which was built from Ashcroft Ashcroft may refer to:

Places

* Ashcroft, British Columbia, a village in Canada

**Ashcroft House in Bagpath, Gloucestershire, England—eponym of the Canadian village

* Ashcroft, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Ashcroft, Colorado, ...

to Telegraph Creek and beyond to Dawson City, Yukon in 1901.

Portions of the telegraph route became part of the Ashcroft trail used by gold seekers during the Klondike gold rush. Of all the trails used by the stampeders the Ashcroft was among the harshest. Of the over fifteen hundred men and three thousand horses left Ashcroft, British Columbia

Ashcroft ( 2016 population: 1,558) is a village in the Thompson Country of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is downstream from the west end of Kamloops Lake, at the confluence of the Bonaparte and Thompson Rivers, and is in the Tho ...

, in the spring of 1898, only six men and no horses reached the goldfields.

Walter R. Hamilton

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

was among those who completed the route. In his book ''The Yukon Story'' he describes the state of the trail thirty years after it was abandoned All evidence of the right-of-way and poles were gone, but in a few instances we found pieces of old telegraph wire imbedded several inches in the spruce, jack-pine and poplar trees that had long-since grown up and over the wires that touched them. I found one of the old green glass insulators still attached to a galvanized wire. I kept it as a souvenir but lost it later with a camera and some clothing when a scow was nearly overturned onLake Laberge Lake Laberge is a widening of the Yukon River north of Whitehorse, Yukon in Canada. It is fifty kilometres long and ranges from two to five kilometres wide. Its water is always very cold, and its weather often harsh and suddenly variable. Names ....

Places named for the expedition or its members

* Mount Pope in British Columbia was named for Franklin Pope, who was the assistant engineer and chief of explorations, responsible for surveying the 1,500 miles section from New Westminster to the Yukon River. * Kennecott, Alaska and the Kennicott Glacier are named for the expedition's naturalist, Robert Kennicott. Although Kennicott died on the expedition, on May 13, 1866, his work was publicized by

* Kennecott, Alaska and the Kennicott Glacier are named for the expedition's naturalist, Robert Kennicott. Although Kennicott died on the expedition, on May 13, 1866, his work was publicized by W. H. Dall

William Healey Dall (August 21, 1845 – March 27, 1927) was an American naturalist, a prominent malacologist, and one of the earliest scientific explorers of interior Alaska. He described many mollusks of the Pacific Northwest of America, and w ...

, another naturalist hired by Robert Kennicott. This publication and the publicity about Kennicott's death at the age of thirty-one helped Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

convince Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

to purchase

Purchasing is the process a business or organization uses to acquire goods or services to accomplish its goals. Although there are several organizations that attempt to set standards in the purchasing process, processes can vary greatly between ...

Alaska from Russia in 1867.

* The Bulkley River, Bulkley Valley, Bulkley Mountains (now named the Bulkley Ranges

The Bulkley Ranges is mountain range in northern British Columbia, Canada, located between the Skeena River, Skeena and Bulkley Rivers south of Hazelton, British Columbia, Hazelton, north of the Morice River and Zymoetz River. It has an area of 78 ...

) and the settlement of Bulkley House Bulkeley or Bulkley is a surname. Notable persons with that surname include:

* Charles Bulkeley Bulkeley-Johnson (1867–1917), British Officer

* Elisabeth Rivers-Bulkeley (1924–2006), Austrian stock broker

* Henry Bulkeley (c. 1641–1698), Eng ...

in British Columbia are named after Colonel Charles Bulkley. The name of the Bulkley-Nechako Regional District, a regional government in that area, is derived from the geographic names.

*Burns Lake

Burns Lake is a rural village in the North-western-Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada, incorporated in 1923. The village had a population of 1,779 as of the 2016 Census.

The village is known for its rich First Nations heritage, and ...

was named after Michael Byrnes, scout for the Collins Overland Telegraph scheme who explored the route from Fort Fraser to Skeena Forks (Hazelton, BC)

* Decker Lake was named after Stephen Decker, construction foreman in British Columbia.

*the Telegraph Range The Telegraph Range is a small hill-range located on the Nechako Plateau to the south of Ootsa Lake in the Cariboo Land District of the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It was named by George M. Dawson to commemorate the route of the ...

in the Ootsa Lake area is one of several landforms whose name is associated with the project

Books and memoirs written about the expedition

Several major works are available documenting the expedition. The scientific travelogue by Smithsonian scientistW. H. Dall

William Healey Dall (August 21, 1845 – March 27, 1927) was an American naturalist, a prominent malacologist, and one of the earliest scientific explorers of interior Alaska. He described many mollusks of the Pacific Northwest of America, and w ...

is perhaps the most referenced, while an English travelogue by Frederick Whymper

Frederick Whymper (20 July 1838 in London – 26 November 1901) was a British artist and explorer.

Biography

Whymper was the eldest son of Elizabeth Whitworth Claridge and Josiah Wood Whymper, a celebrated wood-engraver and artist. His younger ...

provides additional information. Among personal accounts members of the expedition are a diary of Franklin Pope.

George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

and Richard Bush both wrote of the difficulties they encountered during the expedition. Kennan would later become notable for influencing American opinion of the Russian Empire. Originally very much for Russian settlement of the far East, on visiting the exile camps in the 1880s he changed his mind and later wrote ''Tent Life in Siberia: Adventures Among the Koryaks and Other Tribes in Kamchatka and Northern Asia''.1870;reprint 1986 Richard Bush, aiming to emulate Kennan's success, wrote "Reindeer, Dogs and Snowshoes".

All documents and books relating to the expedition are of historical value, not only from a travel and discovery perspective but also from a cultural studies standpoint. The ethnocentric

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

descriptions of aboriginal peoples in the places now known as British Columbia, Yukon Territory

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and Alaska, as well as the general region of Eastern Siberia, typify those attitudes of the time. Telegraph records provide evidence for native land claims such as those of the Gitxsan Nation

Gitxsan (also spelled Gitksan) are an Indigenous people in Canada whose home territory comprises most of the area known as the Skeena Country in English (: means "people of" and : means "the River of Mist"). Gitksan territory encompasses approxim ...

of northern British Columbia. Dall's records have helped locate Smithsonian exhibits returned to their original native domiciles.

Notes

Further reading

* * * * *Kennan, George1870;reprint 1986External links

*Finding Aid to Western Union Telegraph Expedition Collection, 1865–1867

{{DEFAULTSORT:Russian-American Telegraph History of California History of British Columbia History of Yukon Russian Empire–United States relations Russian America History of the telegraph History of telecommunications in the United States Telecommunications in Russia History of science and technology in Russia Military expeditions of the United States Pacific expeditions Telegraph companies Western Union 1865 establishments in the United States 19th century in technology