Ruralism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Agrarianism is a

The United States president

The United States president

Notable agrarian socialists include

Notable agrarian socialists include

In the late 19th century, the

In the late 19th century, the

online edition

* Marx, Leo. ''The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America'' (1964). * Murphy, Paul V. ''The Rebuke of History: The Southern Agrarians and American Conservative Thought'' (2000) *

Parrington, Vernon. ''Main Currents in American Thought'' (1927), 3-vol online

* * Thompson, Paul, and Thomas C. Hilde, eds. ''The Agrarian Roots of Pragmatism'' (2000)

online edition

on Russia and Bulgaria * Kubricht, Andrew Paul. "The Czech Agrarian Party, 1899-1914: a study of national and economic agitation in the Habsburg monarchy" (PhD thesis, Ohio State University Press, 1974) * * Narkiewicz, Olga A. ''The Green Flag: Polish Populist Politics, 1867–1970'' (1976). * Oren, Nissan. ''Revolution Administered: Agrarianism and Communism in Bulgaria'' (1973), focus is post 1945 * Paine, Thomas. ''Agrarian Justice'' (1794) * * Roberts, Henry L. ''Rumania: Political Problems of an Agrarian State'' (1951). *

online edition

*

excerpt and text search

* Sanderson, Steven E. '' Agrarian populism and the Mexican state: the struggle for land in Sonora'' (1981) *Stokes, Eric. ''The Peasant and the Raj: Studies in Agrarian Society and Peasant Rebellion in Colonial India'' (1980) * * Tannenbaum, Frank. ''The Mexican Agrarian Revolution'' (1930)

Writings of a Deliberate AgrarianThe New Agrarian

{{Authority control

political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

and social philosophy

Social philosophy examines questions about the foundations of social institutions, social behavior, and interpretations of society in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social ...

that has promoted subsistence agriculture, smallholding

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology ...

s, and egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, with agrarian political parties normally supporting the rights and sustainability of small farmers and poor peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasant ...

s against the wealthy in society. In highly developed and industrial nations or regions, it can denote use of financial and social incentives for self-sustainability, more community involvement in food production (such as allotment gardens) and smart growth

Smart growth is an urban planning and transportation theory that concentrates growth in compact walkable urban centers to avoid sprawl. It also advocates compact, transit-oriented, walkable, bicycle-friendly land use, including neighborhood sc ...

that avoids urban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city." Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted growt ...

, and also what many of its advocates contend are risks of human overpopulation

Overpopulation or overabundance is a phenomenon in which a species' population becomes larger than the carrying capacity of its environment. This may be caused by increased birth rates, lowered mortality rates, reduced predation or large scal ...

; when overpopulation occurs, the available resources become too limited for the entire population to survive comfortably or at all in the long term.

Philosophy

Some scholars suggest that agrarianism values rural society as superior to urban society and the independent farmer as superior to the paid worker, and sees farming as a way of life that can shape the ideal social values. It stresses the superiority of a simpler rural life as opposed to the complexity of city life. For example, M. Thomas Inge defines agrarianism by the following basic tenets: *Farming is the sole occupation that offers totalindependence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

and self-sufficiency.

*Urban life, capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

, and technology destroy independence and dignity and foster vice and weakness.

*The agricultural community, with its fellowship of labor and co-operation, is the model society.

*The farmer has a solid, stable position in the world order. They have "a sense of identity, a sense of historical and religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

tradition, a feeling of belonging to a concrete family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

, place, and region, which are psychologically and culturally beneficial." The harmony of their life checks the encroachments of a fragmented, alienated modern society.

*Cultivation of the soil "has within it a positive spiritual good" and from it the cultivator acquires the virtues of "honor, manliness, self-reliance, courage, moral integrity, and hospitality." They result from a direct contact with nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

and, through nature, a closer relationship to God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. The agrarian is blessed in that they follow the example of God in creating order out of chaos.

History

The philosophical roots of agrarianism include European and Chinese philosophers. The Chinese school ofAgriculturalism

Agriculturalism, also known as the School of Agrarianism, the School of Agronomists, the School of Tillers, and in Chinese as the ''Nongjia'' (), was an early agrarian Chinese philosophy that advocated peasant utopian communalism and egalitariani ...

(农家/農家) was a philosophy that advocated peasant utopian communalism

Communalism may refer to:

* Communalism (Bookchin), a theory of government in which autonomous communities form confederations

* , a historical method that follows the development of communities

* Communalism (South Asia), violence across ethnic ...

and egalitarianism. In societies influenced by Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or a ...

, the farmer was considered an esteemed productive member of society, but merchants who made money were looked down upon. That influenced European intellectuals like François Quesnay, an avid Confucianist and advocate of China's agrarian policies, in forming the French agrarian philosophy of physiocracy. The physiocrats, along with the ideas of John Locke and the Romantic Era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, formed the basis of modern European and American agrarianism.

Types of agrarianism

Physiocracy

Jeffersonian democracy

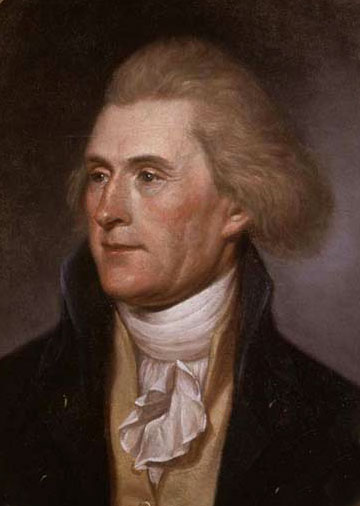

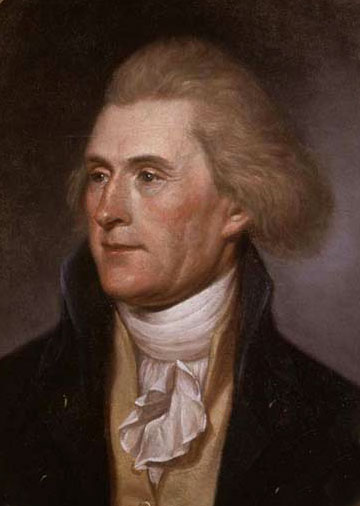

The United States president

The United States president Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

was an agrarian who based his ideas about the budding American democracy around the notion that farmers are “the most valuable citizens” and the truest republicans. Jefferson and his support base were committed to American republicanism

The values, ideals and concept of republicanism have been discussed and celebrated throughout the history of the United States. As the United States has no formal hereditary ruling class, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

, which they saw as being in opposition to aristocracy and corruption, and which prioritized virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standards ...

, exemplified by the "yeoman farmer

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

", "planters

Planters Nut & Chocolate Company is an American snack food company now owned by Hormel Foods. Planters is best known for its processed nuts and for the Mr. Peanut icon that symbolizes them. Mr. Peanut was created by grade schooler Antonio Gentil ...

", and the "plain folk". In praising the rural farmfolk, the Jeffersonians felt that financiers, bankers and industrialists created "cesspools of corruption" in the cities and should thus be avoided.

The Jeffersonians sought to align the American economy more with agriculture than industry. Part of their motive to do so was Jefferson's fear that the over-industrialization of America would create a class of wage laborers who relied on their employers for income and sustenance. In turn, these workers would cease to be independent voters as their vote could be manipulated by said employers. To counter this, Jefferson introduced, as scholar Clay Jenkinson noted, "a graduated income tax that would serve as a disincentive to vast accumulations of wealth and would make funds available for some sort of benign redistribution downward" and tariffs on imported articles, which were mainly purchased by the wealthy. In 1811, Jefferson, writing to a friend, explained: "these revenues will be levied entirely on the rich... . the rich alone use imported articles, and on these alone the whole taxes of the general government are levied. the poor man ... pays not a farthing of tax to the general government, but on his salt."

There is general agreement that the substantial United States' federal policy of offering land grants (such as thousands of gifts of land to veterans) had a positive impact on economic development in the 19th century.

Agrarian socialism

Agrarian socialism is a form of agrarianism that is anti-capitalist in nature and seeks to introducesocialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

economic systems in their stead.

Zapatismo

Notable agrarian socialists include

Notable agrarian socialists include Emiliano Zapata

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (; August 8, 1879 – April 10, 1919) was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the ins ...

who was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution. As part of the Liberation Army of the South

The Liberation Army of the South ( es, Ejército Libertador del Sur, ELS) was a guerrilla force led for most of its existence by Emiliano Zapata that took part in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. During that time, the Zapatistas foug ...

, his group of revolutionaries fought on behalf of the Mexican peasants, whom they saw as exploited by the landowning classes. Zapata published Plan of Ayala

The Plan of Ayala (Spanish: ''Plan de Ayala'') was a document drafted by revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution. In it, Zapata denounced President Francisco Madero for his perceived betrayal of the revolutionary idea ...

, which called for significant land reforms and land redistribution in Mexico as part of the revolution. Zapata was killed and his forces crushed over the course of the Revolution, but his political ideas lived on in the form of Zapatismo.

Zapatismo would form the basis for neozapatismo

Neozapatismo or neozapatism (sometimes simply Zapatismo) is the political philosophy and practice devised and employed by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (, EZLN), who have governed a number of communities in Chiapas, Mexico since th ...

, the ideology of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (, EZLN), often referred to as the Zapatistas (Mexican ), is a far-left political and militant group that controls a substantial amount of territory in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico.

Since ...

. Known as ''Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional'' or EZLN in Spanish, EZLN is a far-left libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (20 ...

political and militant group that emerged in the state of Chiapas in southmost Mexico in 1994. EZLN and Neozapatismo, as explicit in their name, seek to revive the agrarian socialist movement of Zapata, but fuse it with new elements such as a commitment to indigenous rights and community-level decision making.

Subcommander Marcos, a leading member of the movement, argues that the peoples' collective ownership of the land was and is the basis for all subsequent developments the movement sought to create:...When the land became property of the peasants ... when the land passed into the hands of those who work it ...his was His or HIS may refer to: Computing * Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company * Honeywell Information Systems * Hybrid intelligent system * Microsoft Host Integration Server Education * Hangzhou International School, i ...the starting point for advances in government, health, education, housing, nutrition, women’s participation, trade, culture, communication, and information ... t wasrecovering the means of production, in this case, the land, animals, and machines that were in the hands of large property owners.”

Maoism

Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

, the far-left ideology of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

and his followers, places a heavy emphasis on the role of peasants in its goals. In contrast to other Marxist schools of thought which normally seek to acquire the support of urban workers, Maoism sees the peasantry as key. Believing that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun

''Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun'' () is a phrase which was coined by Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong. The phrase was originally used by Mao during an emergency meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on 7 August 1927, ...

", Maoism saw the Chinese Peasantry as the prime source for a Marxist vanguard because it possessed two qualities: (i) they were poor, and (ii) they were a political blank slate; in Mao's words, “A clean sheet of paper has no blotches, and so the newest and most beautiful words can be written on it”. During the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

and the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

, Mao and the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

made extensive use of peasants and rural bases in their military tactics, often eschewing the cities.

Following the eventual victory of the Communist Party in both wars, the countryside and how it should be run remained a focus for Mao. In 1958, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, a social and economic campaign which, amongst other things, altered many aspects of rural Chinese life. It introduced mandatory collective farming

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

and forced the peasantry to organize itself into communal living units which were known as people's communes. These communes, which consisted of 5,000 people on average, were expected to meet high production quotas while the peasants who lived on them adapted to this radically new way of life. The communes were run as co-operatives where wages and money were replaced by work points. Peasants who criticised this new system were persecuted as " rightists" and "counter-revolutionaries

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

". Leaving the communes was forbidden and escaping from them was difficult or impossible, and those who attempted it were subjected to party-orchestrated "public struggle session

Denunciation rallies, also called struggle sessions, were violent public spectacles in Maoist China where people accused of being "Five Black Categories, class enemies" were public humiliation, publicly humiliated, accused, beaten and tortured by ...

s," which further jeopardized their survival. These public criticism sessions were often used to intimidate the peasants into obeying local officials and they often devolved into little more than public beatings.

On the communes, experiments were conducted in order to find new methods of planting crops, efforts were made to construct new irrigation systems on a massive scale, and the communes were all encouraged to produce steel backyard furnaces as part of an effort to increase steel production. However, following the Anti-Rightist Campaign

The Anti-Rightist Campaign () in the People's Republic of China, which lasted from 1957 to roughly 1959, was a political campaign to purge alleged " Rightists" within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the country as a whole. The campaign was ...

, Mao had instilled a mass distrust of intellectuals into China, and thus engineers often were not consulted with regard to the new irrigation systems and the wisdom of asking untrained peasants to produce good quality steel from scrap iron was not publicly questioned. Similarly, the experimentation with the crops did not produce results. In addition to this the Four Pests Campaign

The Four Pests campaign (), was one of the first actions taken in the Great Leap Forward in China from 1958 to 1962. The four pests to be eliminated were rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. The extermination of sparrows is also known as the ...

was launched, in which the peasants were called upon to destroy sparrows and other wild birds that ate crop seeds, in order to protect fields. Pest birds were shot down or scared away from landing until they dropped from exhaustion. This campaign resulted in an ecological disaster that saw an explosion of the vermin population, especially crop-eating insects, which was consequently not in danger of being killed by predators.

None of these new systems were working, but local leaders did not dare to state this, instead, they falsified reports so as not to be punished for failing to meet the quotas. In many cases they stated that they were greatly exceeding their quotas, and in turn, the Chinese state developed a completely false sense of success with regard to the commune system.

All of this culminated in the Great Chinese Famine, which began in 1959, lasted 3 years, and saw an estimated 15 to 30 million Chinese people die. A combination of bad weather and the new, failed farming techniques that were introduced by the state led to massive shortages of food. By 1962, the Great Leap Forward was declared to be at an end.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mao once again radically altered life in rural China with the launching of the Down to the Countryside Movement

The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement, often known simply as the Down to the Countryside Movement, was a policy instituted in the People's Republic of China between mid 1950s and 1978. As a result of what he perceived to ...

. As a response to the Great Chinese Famine, the Chinese President Liu Shaoqi began "sending down" urban youths to rural China in order to recover its population losses and alleviate overcrowding in the cities. However, Mao turned the practice into a political crusade, declaring that the sending down would strip the youth of any bourgeois tendencies by forcing them to learn from the unprivileged rural peasants. In reality, it was the Communist Party's attempt to reign in the Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard lead ...

, who had become uncontrollable during the course of the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

. 10% of the 1970 urban population of China was sent out to remote rural villages, often in Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

. The villages, which were still poorly recovering from the effects of the Great Chinese Famine, did not have the excess resources that were needed to support the newcomers. Furthermore, the so-called "sent-down youth

The sent-down, rusticated, or "educated" youth (), also known as the ''zhiqing'', were the young people who—beginning in the 1950s until the end of the Cultural Revolution, willingly or under coercion—left the urban districts of the ...

" had no agricultural experience and as a result, they were unaccustomed to the harsh lifestyle that existed in the countryside, and their unskilled labor in the villages provided little benefit to the agricultural sector. As a result, many of the sent-down youth died in the countryside. The relocation of the youths was originally intended to be permanent, but by the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party relented and some of those who had the capacity to return to the cities were allowed to do so.

In imitation of Mao's policies, the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

(who were heavily funded and supported by the People's Republic of China) created their own version of the Great Leap Forward which was known as "Maha Lout Ploh". With the Great Leap Forward as its model, it had similarly disastrous effects, contributing to what is now known as the Cambodian genocide. As a part of the Maha Lout Ploh, the Khmer Rouge sought to create an entirely agrarian socialist

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

society by forcibly relocating 100,000 people to move from Cambodia's cities into newly created communes. The Khmer Rouge leader, Pol Pot sought to "purify" the country by setting it back to "Year Zero

A year zero does not exist in the Anno Domini (AD) calendar year system commonly used to number years in the Gregorian calendar (nor in its predecessor, the Julian calendar); in this system, the year is followed directly by year . However, the ...

", freeing it from "corrupting influences". Besides trying to completely de-urbanize Cambodia, ethnic minorities were slaughtered along with anyone else who was suspected of being a "reactionary" or a member of the "bourgeoisie", to the point that wearing glasses was seen as grounds for execution. The killings were only brought to an end when Cambodia was invaded by the neighboring socialist nation of Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, whose army toppled the Khmer Rouge. However, with Cambodia's entire society and economy in disarray, including its agricultural sector, the country still plunged into renewed famine due to vast food shortages. However, as international journalists began to report on the situation and send images of it out to the world, a massive international response was provoked, leading to one of the most concentrated relief efforts of its time.

Notable agrarian parties

Peasant parties first appeared across Eastern Europe between 1860 and 1910, when commercialized agriculture and world market forces disrupted traditional rural society, and the railway and growing literacy facilitated the work of roving organizers. Agrarian parties advocated land reforms to redistribute land on large estates among those who work it. They also wantedvillage cooperatives

Village cooperatives are cooperatives in rural

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural ...

to keep the profit from crop sales in local hands and credit institutions to underwrite needed improvements. Many peasant parties were also nationalist parties because peasants often worked their land for the benefit of landlords of different ethnicity.

Peasant parties rarely had any power before World War I but some became influential in the interwar era, especially in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. For a while, in the 1920s and the 1930s, there was a Green International (International Agrarian Bureau

The International Agrarian Bureau (IAB; cz, Mezinárodní Agrární Bureau, french: Bureau International Agraire), commonly known as the Green International (''Zelená Internacionála'', ''Internationale Verte''), was founded in 1921 by the agrar ...

) based on the peasant parties in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

. It functioned primarily as an information center that spread the ideas of agrarianism and combating socialism on the left and landlords on the right and never launched any significant activities.

Europe

Bulgaria

In Bulgaria, theBulgarian Agrarian National Union

The Bulgarian Agrarian National Union Bulgarian Agrarian National U ...

(BZNS) was organized in 1899 to resist taxes and build cooperatives. BZNS came to power in 1919 and introduced many economic, social, and legal reforms. However, conservative forces crushed BZNS in a 1923 coup and assassinated its leader, Aleksandar Stamboliyski

Aleksandar Stoimenov Stamboliyski ( bg, Александър Стоименов Стамболийски; 1 March 1879 – 14 June 1923) was the prime minister of Bulgaria from 1919 until 1923.

Stamboliyski was a member of the Agrarian Union, ...

(1879–1923). BZNS was made into a communist puppet group until 1989, when it reorganized as a genuine party.

Czechoslovakia

InCzechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, the Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People sk, Republikánska strana zemedelského a maloroľníckeho ľudu

, logo =

, leader = Stanislav Kubr Josef Žďárský Antonín ŠvehlaRudolf Beran

, foundation =

, dissolution =

, merged = Party of National Unity

, you ...

often shared power in parliament as a partner in the five-party pětka coalition. The party's leader, Antonín Švehla

Antonín Švehla (15 April 1873, in Prague – 12 December 1933 in Prague) was a Czechoslovak politician. He served three terms as the prime minister of Czechoslovakia. He is regarded as one of the most important political figures of the First C ...

(1873–1933), was prime minister several times. It was consistently the strongest party, forming and dominating coalitions. It moved beyond its original agrarian base to reach middle-class voters. The party was banned by the National Front after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

.

France

InFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the Hunting, Fishing, Nature, Tradition

The Rurality Movement (, LMR), formerly Hunting, Fishing, Nature and Traditions (french: Chasse, pêche, nature et traditions; ; CPNT, ) is an agrarianist political party in France that aims to defend the traditional values of rural France. I ...

party is a moderate conservative, agrarian party, reaching a peak of 4.23% in the 2002 French presidential election

Presidential elections were held in France on 21 April 2002, with a runoff election between the top two candidates, incumbent Jacques Chirac of the Rally for the Republic and Jean-Marie Le Pen of the National Front, on 5 May. This presidential ...

. It would later on become affiliated to France's main conservative party, Union for a Popular Movement

The Union for a Popular Movement (french: link=no, Union pour un mouvement populaire, ; UMP, ) was a centre-right List of political parties in France, political party in France that was one of the two major party, major contemporary political pa ...

. More recently, the Resistons! movement of Jean Lassalle

Jean Lassalle (; oc, Joan de Lassala; born 3 May 1955) is a French politician who represented the 4th constituency of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in the National Assembly from 2002 to 2022. A former member of the Democratic Movement ...

espoused agrarianism.

Hungary

In Hungary, the first major agrarian party, the small-holders party was founded in 1908. The party became part of the government in the 1920s but lost influence in the government. A new party, theIndependent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party

The Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party ( hu, Független Kisgazda-, Földmunkás- és Polgári Párt), known mostly by its acronym FKgP or its shortened form Independent Smallholders' Party ( hu, Független Kisgazdapárt), ...

was established in 1930 with a more radical program representing larger scale land redistribution initiatives. They implemented this program together with the other coalition parties after WWII. However, after 1949 the party was outlawed when a one-party system was introduced. They became part of the government again 1990–1994, and 1998-2002 after which they lost political support. The ruling Fidesz

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (; hu, Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Hungary, led by Viktor Orbán.

It was formed in 1988 under the name of Alliance of Young ...

party has an agrarian faction, and promotes agrarian interest since 2010 with the emphasis now placed on supporting larger family farms versus small-holders.

Ireland

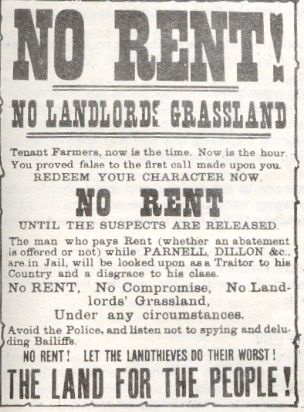

Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

aimed to abolish landlordism in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on. The "Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

" of 1878–1909 led to the Irish Land Acts

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

, ending absentee landlords

In economics, an absentee landlord is a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. The term "absentee ownership" was popularised by economist Thorstein Veblen's 1923 bo ...

and ground rent and redistributing land among peasant farmers.

Post-independence, the Farmers' Party operated in the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

from 1922, folding into the National Centre Party in 1932. It was mostly supported by wealthy farmers in the east of Ireland.

Clann na Talmhan

Clann na Talmhan (, "Family/Children of the land"; formally known as the ''National Agricultural Party'') was an Irish agrarian political party active between 1939 and 1965.

Formation and growth

Clann na Talmhan was founded on 29 June 1939 in ...

(Family of the Land; also called the ''National Agricultural Party'') was founded in 1938. They focused more on the poor smallholders of the west, supporting land reclamation, afforestation, social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

and rates reform. They formed part of the governing coalition of the Government of the 13th Dáil

The Government of the 13th Dáil or the 5th Government of Ireland (18 February 1948 – 13 June 1951) was the government of Ireland formed after the general election held on 4 February 1948 — commonly known as the First Inter-Party Governme ...

and Government of the 15th Dáil. Economic improvement in the 1960s saw farmers vote for other parties and Clann na Talmhan disbanded in 1965.

Latvia

In Latvia, theUnion of Greens and Farmers

The Union of Greens and Farmers ( lv, Zaļo un Zemnieku savienība, ZZS) is an agrarian political alliance in Latvia. It is made up of the Latvian Farmers' Union, Latvian Social Democratic Workers' Party, and For Latvia and Ventspils.

It is p ...

is supportive of traditional small farms and perceives them as more environmentally friendly than large-scale farming: Nature is threatened by development, while small farms are threatened by large industrial-scale farms.

Lithuania

In Lithuania, as of 2017, the government is led by theLithuanian Farmers and Greens Union

The Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union ( lt, Lietuvos valstiečių ir žaliųjų sąjunga, LVŽS)The party is also known as Lithuanian Peasant and Greens Union. is a green-conservative and agrarian political party in Lithuania led by Ram ...

, under the leadership of industrial farmer Ramūnas Karbauskis.

Nordic countries

Poland

InPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the Polish People's Party

The Polish People's Party ( pl, Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, PSL) is an agrarian political party in Poland. It is currently led by Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz.

Its history traces back to 1895, when it held the name People's Party, although i ...

traces its tradition to an agrarian party in Austro-Hungarian-controlled Galician Poland. After the fall of the communist regime, PPP's biggest success came in 1993 elections, where it won 132 out of 460 parliamentary seats. Since then, PPP's support has steadily declined, until 2019, when they formed Polish Coalition

The Polish Coalition ( pl, Koalicja Polska, KP) is a political alliance in Poland. It is led by the Polish People's Party.

It was formed in 2019. In the 2019 parliamentary election, the Polish Coalition placed fourth, winning 30 seats in tot ...

with an anti- establishment, direct democracy Kukiz'15

Kukiz'15 is a right-wing populist political party in Poland led by Paweł Kukiz.

It was formed in 2015 as a loose movement that registered itself as an association in 2016 and later as a political party in 2020. Initially, it was connected wit ...

party, and managed to get 8.5% of votes. Moreover, PPP tends to get much better results in local elections. In 2014 elections they have managed to get 23.88% of votes.

The right-wing Law and Justice party has also become supportive of agrarian policies in recent years and polls show that most of their support comes from rural areas. AGROunia

The AGROunion ( pl, AGROunia, AU) is a conservative agrarianisthttps://europeelects.eu/poland/ Orientation: Conservative, Farmers’ interest (self-declared) political movement in Poland formed by Michał Kołodziejczak AGROunia criticizes the ...

resembles the features of agrarianism.

Romania

InRomania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, older parties from Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

, and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

merged to become the National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...

in 1926. Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

(1873–1953) was a prime minister with an agrarian cabinet from 1928 to 1930 and briefly in 1932–1933, but the Great Depression made proposed reforms impossible. The communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

dissolved the party in 1947, but it reformed in 1989 after they fell from power.

The reformed party, which also incorporated elements of Christian democracy in its ideology, governed Romania as part of the Romanian Democratic Convention

The Romanian Democratic Convention ( ro, Convenţia Democrată Română or Convenția Democratică Română; abbreviated CDR) was an electoral alliance of several democratic, anti-Communist, anti-totalitarian, and centre-right political parties i ...

between 1996 and 2000.

Serbia

In Serbia,Nikola Pašić

Nikola Pašić ( sr-Cyrl, Никола Пашић, ; 18 December 1845 – 10 December 1926) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and diplomat who was a leading political figure for almost 40 years. He was the leader of the People's Radical ...

(1845–1926) and his People's Radical Party

The People's Radical Party ( sr, Народна радикална странка, Narodna radikalna stranka, abbr. НРС or NRS) was the dominant ruling party of Kingdom of Serbia and later Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from the l ...

dominated Serbian politics after 1903. The party also monopolized power in Yugoslavia from 1918 to 1929. During the dictatorship of the 1930s, the prime minister was from that party.

Ukraine

In Ukraine, the Radical Party of Oleh Lyashko has promised to purify the country ofoligarchs

Oligarch may refer to:

Authority

* Oligarch, a member of an oligarchy, a power structure where control resides in a small number of people

* Oligarch (Kingdom of Hungary), late 13th–14th centuries

* Business oligarch, wealthy and influential bu ...

"with a pitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to ...

". The party advocates a number of traditional left-wing positions (a progressive tax structure, a ban on agricultural land sale and eliminating the illegal land market, a tenfold increase in budget spending on health, setting up primary health centres in every village)The Communist Party May Be on Its Last Legs, But Social Populism is Still AliveThe Ukrainian Week

''The Ukrainian Week'' ( uk, Український Тиждень, translit=Ukrainskyi Tyzhden) is an illustrated weekly magazine covering politics, economics and the arts and aimed at the socially engaged Ukrainian-language reader. It provides ...

(23 October 2014) and mixes them with strong nationalist sentiments.

United Kingdom

In land law the heyday of English, Irish (and thus Welsh) agrarianism was to 1603, led by the Tudor royal advisors, who sought to maintain a broad pool of agricultural commoners from which to draw military men, against the interests of larger landowners who soughtenclosure

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or " common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

(meaning complete private control of common land, over which by custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

and common law lords of the manor always enjoyed minor rights). The heyday was eroded by hundreds of Acts of Parliament to expressly permit enclosure, chiefly from 1650 to the 1810s. Politicians standing strongly as reactionaries to this included the Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populis ...

, those anti-industrialists (Luddites

The Luddites were a secret oath-based organisation of English textile workers in the 19th century who formed a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery. The group is believed to have taken its name from Ned Ludd, a legendary weaver ...

) going beyond opposing new weaving technology and, later, radicals such as William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

.

A high level of net national or local self-sufficiency has a strong base in campaigns and movements. In the 19th century such empowered advocates included Peelites and most Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

. The 20th century saw the growth or start of influential non-governmental organisations, such as the National Farmers' Union of England and Wales

The National Farmers' Union (NFU) is a member organisation/industry association for farmers in England and Wales. It is the largest farmers' organisation in the countries, and has over 300 branch offices.

History

On 10 December 1908, a meetin ...

, Campaign for Rural England

CPRE, The Countryside Charity, formerly known by names such as the ''Council for the Preservation of Rural England'' and the ''Council for the Protection of Rural England'', is a charity in England with over 40,000 members and supporters. Forme ...

, Friends of the Earth (EWNI)

Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland (also known as FoE EWNI) is one of 75 national groups around the world which make up the Friends of the Earth network of environmental organisations. It is usually referred to as just 'F ...

and of the England Wales, Scottish and Northern Irish political parties prefixed by and focussed on Green politics

Green politics, or ecopolitics, is a political ideology that aims to foster an ecologically sustainable society often, but not always, rooted in environmentalism, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy. Wall 2010. p. 12-13. It b ...

. The 21st century has seen decarbonisation already in electricity markets. Following protests and charitable lobbying local food

Local food is food that is produced within a short distance of where it is consumed, often accompanied by a social structure and supply chain different from the large-scale supermarket system.

Local food (or "locavore") movements aim to con ...

has seen growing market share, sometimes backed by wording in public policy papers and manifestos. The UK has many sustainability-prioritising businesses, green charity campaigns, events and lobby groups ranging from espousing allotment garden

An allotment (British English), or in North America, a community garden, is a plot of land made available for individual, non-commercial gardening or growing food plants, so forming a kitchen garden away from the residence of the user. Such plot ...

s (hobby community farming) through to a clear policy of local food and/or self-sustainability models.

Oceania

Australia

Historian F.K. Crowley finds that: TheNational Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia, also known as The Nationals or The Nats, is an List of political parties in Australia, Australian political party. Traditionally representing graziers, farmers, and regional voters generally, it began as the Au ...

(formerly called the Country Party), from the 1920s to the 1970s, promulgated its version of agrarianism, which it called "countrymindedness". The goal was to enhance the status of the graziers (operators of big sheep stations) and small farmers and justified subsidies for them.

New Zealand

TheNew Zealand Liberal Party

The New Zealand Liberal Party was the first organised political party in New Zealand. It governed from 1891 until 1912. The Liberal strategy was to create a large class of small land-owning farmers who supported Liberal ideals, by buying larg ...

aggressively promoted agrarianism in its heyday (1891–1912). The landed gentry and aristocracy ruled Britain at this time. New Zealand never had an aristocracy but its wealthy landowners largely controlled politics before 1891. The Liberal Party set out to change that by a policy it called " populism." Richard Seddon

Richard John Seddon (22 June 1845 – 10 June 1906) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 15th premier (prime minister) of New Zealand from 1893 until his death. In office for thirteen years, he is to date New Zealand's longest-se ...

had proclaimed the goal as early as 1884: "It is the rich and the poor; it is the wealthy and the landowners against the middle and labouring classes. That, Sir, shows the real political position of New Zealand." The Liberal strategy was to create a large class of small landowning farmers who supported Liberal ideals. The Liberal government Liberal government may refer to:

Australia

In Australian politics, a Liberal government may refer to the following governments administered by the Liberal Party of Australia:

* Menzies Government (1949–66), several Australian ministries under S ...

also established the basis of the later welfare state such as old age pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

and developed a system for settling industrial disputes, which was accepted by both employers and trade unions. In 1893, it extended voting rights to women, making New Zealand the first country in the world to do so.

To obtain land for farmers, the Liberal government from 1891 to 1911 purchased of Maori land. The government also purchased from large estate holders for subdivision and closer settlement by small farmers. The Advances to Settlers Act (1894) provided low-interest mortgages, and the agriculture department disseminated information on the best farming methods. The Liberals proclaimed success in forging an egalitarian, anti-monopoly land policy. The policy built up support for the Liberal Party in rural North Island electorates. By 1903, the Liberals were so dominant that there was no longer an organized opposition in Parliament.

North America

The United States and Canada both saw a rise of Agrarian-oriented parties in the early twentieth century as economic troubles motivated farming communities to become politically active. It has been proposed that different responses to agrarian protest largely determined the course of power generated by these newly-energized rural factions. According to Sociologist Barry Eidlin:"In the United States, Democrats adopted a co-optive response to farmer and labor protest, incorporating these constituencies into the New Deal coalition. In Canada, both mainstream parties adopted a coercive response, leaving these constituencies politically excluded and available for an independent left coalition."These reactions may have helped determine the outcome of agrarian power and political associations in the US and Canada.

United States of America

= Kansas

= Economic desperation experienced by farmers across the state of Kansas in the nineteenth century spurred the creation of The People's Party in 1890, and soon-after would gain control of the governor's office in 1892. This party, consisting of a mix of Democrats, Socialists, Populists, and Fusionists, would find itself buckling from internal conflict regarding the unlimited coinage of silver. The Populists permanently lost power in 1898.= Oklahoma

= Oklahoma farmers considered their political activity during the early twentieth century due to the outbreak of war, depressed crop prices, and an inhibited sense of progression towards owning their own farms. Tenancy had been reportedly as high as 55% in Oklahoma by 1910. These pressures saw agrarian counties in Oklahoma supporting Socialist policies and politics, with the Socialist platform proposing a deeply agrarian-radical platform:...the platform proposed a "Renters and Farmer's Program" which was strongly agrarian radical in its insistence upon various measures to put land into "The hands of the actual tillers of the soil." Although it did not propose to nationalize privately owned land, it did offer numerous plans to enlarge the state's public domain, from which land would be rented at prevailing share rents to tenants until they had paid rent equal to the land's value. The tenant and his children would have the right of occupancy and use, but the 'title' would remind in the 'commonwealth', an arrangement that might be aptly termed 'Socialist fee simple'. They proposed to exempt from taxation all farm dwellings, animals, and improvements up to the value of $1,000. The State Board of Agriculture would encourage 'co-operative societies' of farmers to make plans f or the purchase of land, seed, tools, and for preparing and selling produce. In order to give farmers essential services at cost, the Socialists called for the creation of state banks and mortgage agencies, crop insurance, elevators, and warehouses.This agrarian-backed Socialist party would win numerous offices, causing a panic within the local Democratic party. This agrarian-Socialist movement would be inhibited by voter suppression laws aimed at reducing the participation of voters of color, as well as national wartime policies intended to disrupt political elements considered subversive. This party would peak in power in 1914.

Back-to-the-land movement

Agrarianism is similar to but not identical with theback-to-the-land movement

A back-to-the-land movement is any of various agrarian movements across different historical periods. The common thread is a call for people to take up smallholding and to grow food from the land with an emphasis on a greater degree of self-suffic ...

. Agrarianism concentrates on the fundamental goods of the earth, on communities of more limited economic and political scale than in modern society, and on simple living, even when the shift involves questioning the "progressive" character of some recent social and economic developments. Thus, agrarianism is not industrial farming

Industrial agriculture is a form of modern farming that refers to the industrialized production of crops and animals and animal products like eggs or milk. The methods of industrial agriculture include innovation in agricultural machinery and far ...

, with its specialization on products and industrial scale.Jeffrey Carl Jacob, ''New Pioneers: The Back-to-the-Land Movement and the Search for a Sustainable Future'' (Penn State University Press. 1997)

See also

*Agrarian socialism

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

* Farmer–Labor Party

The first modern Farmer–Labor Party in the United States emerged in Minnesota in 1918. Economic dislocation caused by American entry into World War I put agricultural prices and workers' wages into imbalance with rapidly escalating retail price ...

, USA early 20th century

*Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

* Labour-Farmer Party, Japan 1920s

* Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party

The Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party (FL) was a left-wing American political party in Minnesota between 1918 and 1944. Largely dominating Minnesota politics during the Great Depression, it was one of the most successful statewide third party movem ...

, USA early 20th century

*Nordic agrarian parties The Nordic agrarian parties, also referred to as Nordic Centre parties, Scandinavian agrarian parties or Agrarian Liberal parties are agrarian political parties that belong to a political tradition particular to the Nordic countries. Positioning th ...

*Yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, English farmers

References

Further reading

Agrarian values

* Brass, Tom. ''Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism: The Return of the Agrarian Myth'' (2000) * * * * * Inge, M. Thomas. ''Agrarianism in American Literature'' (1969) * Kolodny, Annette. ''The Land before Her: Fantasy and Experience of the American Frontiers, 1630–1860'' (1984)online edition

* Marx, Leo. ''The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America'' (1964). * Murphy, Paul V. ''The Rebuke of History: The Southern Agrarians and American Conservative Thought'' (2000) *

Parrington, Vernon. ''Main Currents in American Thought'' (1927), 3-vol online

* * Thompson, Paul, and Thomas C. Hilde, eds. ''The Agrarian Roots of Pragmatism'' (2000)

Primary sources

* Sorokin, Pitirim A. et al., eds. ''A Systematic Source Book in Rural Sociology'' (3 vol. 1930) vol 1 pp. 1–146 covers many major thinkers down to 1800Europe

* * Bell, John D. ''Peasants in Power: Alexander Stamboliski and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, 1899–1923''(1923) * Donnelly, James S. ''Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821–1824'' (2009) * Donnelly, James S. ''Irish Agrarian Rebellion, 1760–1800'' (2006) * Gross, Feliks, ed. ''European Ideologies: A Survey of 20th Century Political Ideas'' (1948) pp. 391–48online edition

on Russia and Bulgaria * Kubricht, Andrew Paul. "The Czech Agrarian Party, 1899-1914: a study of national and economic agitation in the Habsburg monarchy" (PhD thesis, Ohio State University Press, 1974) * * Narkiewicz, Olga A. ''The Green Flag: Polish Populist Politics, 1867–1970'' (1976). * Oren, Nissan. ''Revolution Administered: Agrarianism and Communism in Bulgaria'' (1973), focus is post 1945 * Paine, Thomas. ''Agrarian Justice'' (1794) * * Roberts, Henry L. ''Rumania: Political Problems of an Agrarian State'' (1951). *

North America

* * * Goodwyn, Lawrence. ''The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America'' (1978), 1880s and 1890s in U.S. * * * Lipset, Seymour Martin. ''Agrarian socialism: the Coöperative Commonwealth Federation in Saskatchewan'' (1950), 1930s-1940s * McConnell, Grant. ''The decline of agrarian democracy''(1953), 20th century U.S. * Mark, Irving. ''Agrarian conflicts in colonial New York, 1711–1775'' (1940) * Ochiai, Akiko. ''Harvesting Freedom: African American Agrarianism in Civil War Era South Carolina'' (2007) * Robison, Dan Merritt. ''Bob Taylor and the agrarian revolt in Tennessee'' (1935) * Stine, Harold E. ''The agrarian revolt in South Carolina;: Ben Tillman and the Farmers' Alliance'' (1974) * Summerhill, Thomas. ''Harvest of Dissent: Agrarianism in Nineteenth-Century New York'' (2005) * Szatmary, David P. ''Shays' Rebellion: The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection'' (1984), 1787 in Massachusetts * Woodward, C. Vann. '' Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel'' (1938online edition

*

Global South

* Brass, Tom (ed.). ''New Farmers' Movements in India'' (1995) 304 pages. * * *Handy, Jim. ''Revolution in the Countryside: Rural Conflict and Agrarian Reform in Guatemala, 1944–1954'' (1994) * * * Paige, Jeffery M. '' Agrarian revolution: social movements and export agriculture in the underdeveloped world'' (1978) 435 pageexcerpt and text search

* Sanderson, Steven E. '' Agrarian populism and the Mexican state: the struggle for land in Sonora'' (1981) *Stokes, Eric. ''The Peasant and the Raj: Studies in Agrarian Society and Peasant Rebellion in Colonial India'' (1980) * * Tannenbaum, Frank. ''The Mexican Agrarian Revolution'' (1930)

External links

Writings of a Deliberate Agrarian

{{Authority control