Royal Prussian Army of the Napoleonic Wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While  The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The

The Royal Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the cor ...

was the principal armed force

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

during its participation in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

.

Frederick the Great's successor, his nephew Frederick William II (1786–97), relaxed conditions in Prussia and had little interest in war. He delegated responsibility to the aged Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick

Charles William Ferdinand (german: Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand; 9 October 1735 – 10 November 1806) was the Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and a military leader. His titles are usually shortened to Duke of Brunswic ...

, and the army began to degrade in quality. Led by veterans of the Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars (german: Schlesische Kriege, links=no) were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg Austria (under Archduchess Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

, the Prussian Army was ill-equipped to deal with Revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. The officers retained the same training, tactics, and weaponry used by Frederick the Great some forty years earlier. In comparison, the revolutionary army of France, especially under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, was developing new methods of organization, supply, mobility, and command.

Prussia withdrew from the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that succ ...

in the Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The sec ...

(1795), ceding the Rhenish territories to France. Upon Frederick William II's death in 1797, the state was bankrupt and the army outdated.

War of the Fourth Coalition 1806–1807

He was succeeded by his son,Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

(1797–1840), who involved Prussia in the disastrous Fourth Coalition. The Prussian Army was decisively defeated in the battles of Saalfeld

Saalfeld (german: Saalfeld/Saale) is a town in Germany, capital of the Saalfeld-Rudolstadt district of Thuringia. It is best known internationally as the ancestral seat of the Saxe-Coburg and Gotha branch of the Saxon House of Wettin.

Geography ...

, Jena, and Auerstedt in 1806. The Prussians' famed discipline collapsed and led to widescale surrendering among infantry, cavalry, and garrisons. While some Prussian commanders acquitted themselves well, such as L'Estocq

The L'Estocq family is a German noble family of French-Huguenot origin. Members of the family held significant military positions in the Kingdom of Prussia and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental count ...

at Eylau, Gneisenau at Kolberg, and Blücher at Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, they were not enough to reverse Jena-Auerstedt. Prussia submitted to major territorial losses, a standing army of only 42,000 men, and an alliance with France in the Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

(1807).

Reform

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While

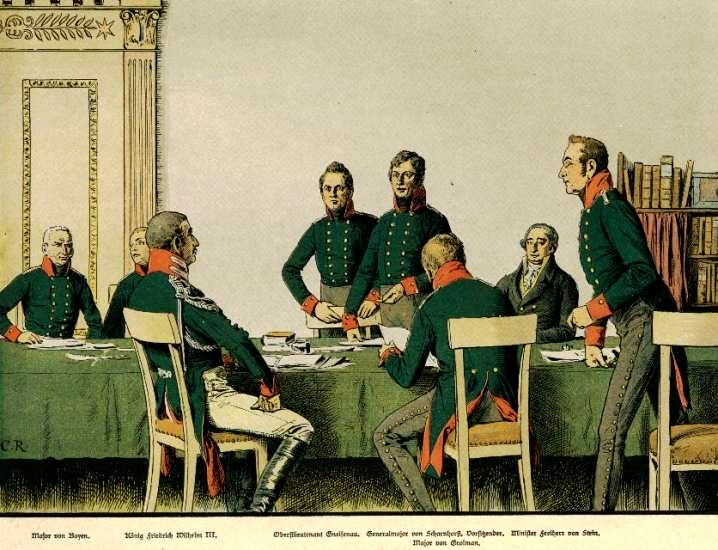

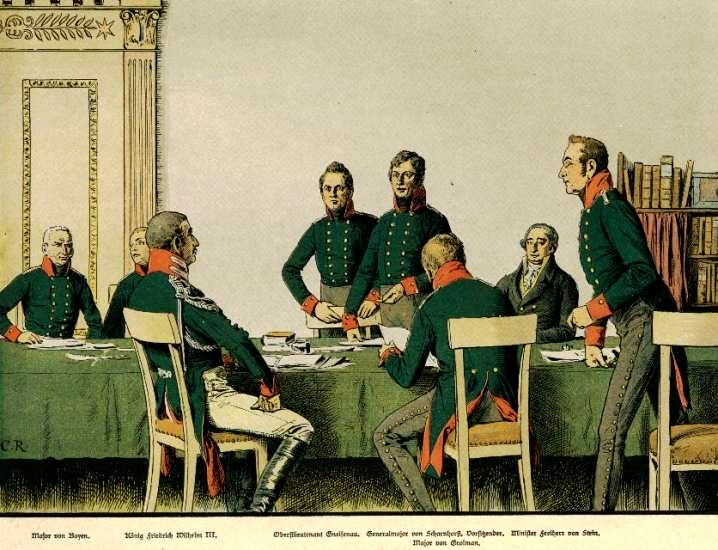

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While Stein

Stein is a German, Yiddish and Norwegian word meaning "stone" and "pip" or "kernel". It stems from the same Germanic root as the English word stone. It may refer to:

Places In Austria

* Stein, a neighbourhood of Krems an der Donau, Lower Aust ...

and Hardenberg

Hardenberg (; nds-nl, Haddenbarreg or '' 'n Arnbarg'') is a city and municipality in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands. The municipality of Hardenberg has a population of about 60,000, with about 19,000 living in the city. It recei ...

began modernizing the Prussian state, Scharnhorst began to reform the military. He led a Military Reorganization Committee, which included Gneisenau, Grolman, Boyen, and the civilians Stein and Könen.. Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottfried (or Gottlieb) von Clausewitz (; 1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral", in modern terms meaning psychological, and political aspects of waging war. His mos ...

assisted with the reorganization as well. Dismayed by the populace's indifferent reaction to the 1806 defeats, the reformers wanted to cultivate patriotism within the country. Stein's reforms abolished serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

in 1807 and initiated local city government in 1808.

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

;. many were allowed to redeem their reputations in the war of 1813. The officer corps was reopened to the middle class in 1808, while advancement into the higher ranks became based on education. King Frederick William III created the War Ministry in 1809, and Scharnhorst founded an officer's training school, the later Prussian War Academy

The Prussian Staff College, also Prussian War College (german: Preußische Kriegsakademie) was the highest military facility of the Kingdom of Prussia to educate, train, and develop general staff officers.

Location

It originated with the ''Ak ...

, in Berlin in 1810.

Scharnhorst advocated adopting the '' levée en masse'', the military conscription used by France. He created the ''Krümpersystem'', by which companies replaced 3–5 men monthly, allowing up to 60 extra men to be trained annually per company. This system granted the army a larger reserve of 30,000–150,000 extra troops The ''Krümpersystem'' was also the beginning of short-term compulsory service in Prussia, as opposed to the long-term conscription previously used. Because the occupying French prohibited the Prussians from forming divisions, the Prussian Army was divided into six brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

s, each consisting of seven to eight infantry battalions and twelve squadrons of cavalry. The combined brigades were supplemented with three brigades of artillery.

Corporal punishment was by and large abolished, while soldiers were trained in the field and in tirailleur

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French ...

tactics. Scharnhorst promoted the integration of the infantry, cavalry, and artillery through combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects (for example by using infantry and armour in an urban environment in which each supports the other) ...

, as opposed to their previous independent states. Equipment and tactics were updated in respect to the Napoleonic campaigns. The field manual issued by Yorck

''Yorck'' is a 1931 German war film directed by Gustav Ucicky and starring Werner Krauss, Grete Mosheim and Rudolf Forster.Noack p.59 It portrays the life of the Prussian General Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg, particularly his refusal to serve i ...

in 1812 emphasized combined arms and faster marching speeds. In 1813, Scharnhorst succeeded in attaching a chief of staff trained at the academy to each field commander.

Some reforms were opposed by Frederician traditionalists, such as Yorck, who felt that middle class officers would erode the privileges of the aristocratic officer corps and promote the ideas of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. The army reform movement was cut short by Scharnhorst's death in 1813, and the shift to a more democratic and middle class military began to lose momentum in the face of the reactionary government.

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

in its 1809 campaign against France. When the cautious king refused to support a new Prussian war, however, Schill led his hussar regiment against the occupying French, expecting to provoke a national uprising. The king considered Schill a mutineer, and the major's rebellion was crushed at Stralsund by French allies..

French invasion of Russia

The Franco-Prussian treaty of 1812 forced Prussia to provide 20,000 troops to Napoleon's Grande Armée, first under the leadership of Grawert and then under Yorck. The French occupation of Prussia was reaffirmed, and 300 demoralized Prussian officers resigned in protest. During Napoleon's retreat from Russia in 1812, Yorck independently signed theConvention of Tauroggen

The Convention of Tauroggen was an armistice signed 30 December 1812 at Tauroggen (now Tauragė, Lithuania) between General Ludwig Yorck on behalf of his Prussian troops and General Hans Karl von Diebitsch of the Imperial Russian Army. Yorck's ...

with Russia, breaking the Franco-Prussian alliance. Stein arrived in East Prussia and led the raising of ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortificatio ...

'' (militia) to defend the province. With Prussia's joining of the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

out of his hands, Frederick William III quickly began to mobilize the army, and the East Prussian ''Landwehr'' was duplicated in the rest of the country. In comparison to 1806, the Prussian populace, especially the middle class, was supportive of the war, and thousands of volunteers joined the army. Prussian troops under the leadership of Blücher and Gneisenau proved vital at the Battles of Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

(1813) and Waterloo (1815). Later staff officers were impressed with the simultaneous operations of separate groups of the Prussian Army.

The Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

was introduced as a military decoration by King Frederick William III in 1813. After the publication of his ''On War

''Vom Kriege'' () is a book on war and military strategy by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832. ...

'', Clausewitz became a widely studied philosopher of war.

Wars of Liberation

The Prussian, and laterGerman General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

, which developed out of meetings of the Great Elector with his senior officers and the informal meeting of the Napoleonic Era reformers, was formally created in 1814. In the same year Boyen and Grolman drafted a law for universal conscription, by which men would successively serve in the standing army, the ''Landwehr'', and the local ''Landsturm

In German-speaking countries, the term ''Landsturm'' was historically used to refer to militia or military units composed of troops of inferior quality. It is particularly associated with Prussia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Sweden and the Nethe ...

'' until the age of 39. Troops of the 136,000-strong standing army served for three years and were in the reserves for two, while militiamen of the 163,000-strong ''Landwehr'' served a few weeks annually for seven years.} Boyen and Blücher strongly supported the 'civilian army' of the ''Landwehr'', which was to unite military and civilian society, as an equal to the standing army.

The Convention of Tauroggen

The Convention of Tauroggen was an armistice signed 30 December 1812 at Tauroggen (now Tauragė, Lithuania) between General Ludwig Yorck on behalf of his Prussian troops and General Hans Karl von Diebitsch of the Imperial Russian Army. Yorck's ...

became the starting-point of Prussia's regeneration. As the news of the destruction of the '' Grande Armée'' spread, and the appearance of countless stragglers convinced the Prussian people of the reality of the disaster, the spirit generated by years of French domination burst out. For the moment the king and his ministers were placed in a position of the greatest anxiety, for they knew the resources of France and the boundless versatility of their arch-enemy far too well to imagine that the end of their sufferings was yet in sight. To disavow the acts and desires of the army and of the secret societies for defence with which all north Germany was honeycombed would be to imperil the very existence of the monarchy, whilst an attack on the wreck of the Grand Army meant the certainty of a terrible retribution from the new armies now rapidly forming on the Rhine.

But the Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

and the soldiers were resolved to continue the campaign, and working in collusion they put pressure on the not unwilling representatives of the civil power to facilitate the supply and equipment of such troops as were still in the field; they could not refuse food and shelter to their starving countrymen or their loyal allies, and thus by degrees the French garrisons scattered about the country either found themselves surrounded or were compelled to retire to avoid that fate. Thus it happened that the viceroy of Italy felt himself compelled to depart from the positive injunctions of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

to hold on at all costs to his advanced position at Posen, where about 14,000 men had gradually rallied around him, and to withdraw step by step to Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

, where he met reinforcements and commanded the whole course of the lower Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

.

Hundred Days

Prussian Army (Army of the Lower Rhine)

This army was composed entirely of Prussians from the provinces of theKingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

, old and recently acquired alike. Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt (; 21 December 1742 – 12 September 1819), ''Graf'' (count), later elevated to ''Fürst'' (sovereign prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Prussian '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal). He earne ...

commanded this army with General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau

August Wilhelm Antonius Graf Neidhardt von Gneisenau (27 October 176023 August 1831) was a Prussian field marshal. He was a prominent figure in the reform of the Prussian military and the War of Liberation.

Early life

Gneisenau was born at Schil ...

as his chief of staff and second in command.

Blücher's Prussian army of 116,000 men, with headquarters at Namur, was distributed as follows:

*I Corps ( Graf von Zieten), 30,800, cantoned along the Sambre, headquarters Charleroi, and covering the area Fontaine-l'Évêque

Fontaine-l'Évêque (; wa, Fontinne-l'-Eveke) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

On January 1, 2006, Fontaine-l'Évêque had a total population of 16,687. The total area is 28.41 km² which ...

–Fleurus

Fleurus (; wa, Fleuru) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It has been the site of four major battles.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Brye, Heppignies, Fleurus, Lambusart, ...

– Moustier.

*II Corps ( Pirch I), 31,000, headquarters at Namur, lay in the area Namur- Hannut–Huy

Huy ( or ; nl, Hoei, ; wa, Hu) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium. Huy lies along the river Meuse, at the mouth of the small river Hoyoux. It is in the ''sillon industriel'', the former industrial ...

.

*III Corps ( Thielemann), 23,900, in the bend of the river Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a t ...

, headquarters Ciney

Ciney (; wa, Cînè) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. As of 2018, Ciney had a total population of 16,439. The total area is 147.56 km² which gives a population density of 111 inhabitants per k ...

, and disposed in the area Dinant–Huy

Huy ( or ; nl, Hoei, ; wa, Hu) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium. Huy lies along the river Meuse, at the mouth of the small river Hoyoux. It is in the ''sillon industriel'', the former industrial ...

–Ciney

Ciney (; wa, Cînè) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. As of 2018, Ciney had a total population of 16,439. The total area is 147.56 km² which gives a population density of 111 inhabitants per k ...

.

*IV Corps ( Bülow), 30,300, with headquarters at Liège and cantoned around it.

German Corps ( North German Federal Army)

This army was part of the Prussian Army above, but was to act independently much further south. It was composed of contingents from the following nations of theGerman Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

: Electorate of Hessen, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

The Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was a territory in Northern Germany held by the House of Mecklenburg residing at Schwerin. It was a sovereign member state of the German Confederation and became a federated state of the North German Con ...

, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

The Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was a duchy in northern Germany consisting of the eastern fifth of the historic Mecklenburg region, roughly corresponding with the present-day Mecklenburg-Strelitz district (the former Lordship of Stargard), ...

, Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (german: Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) was a historical German state, created as a duchy in 1809 by the merger of the Ernestine duchies of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach, which had been in personal union since 1741. It was ra ...

, Duchy of Oldenburg (state)

Oldenburg is a former state in northwestern Germany whose capital was Oldenburg. The region gained its independence in the High Middle Ages. It survived the Napoleonic Wars as an independent country, formed part of the German Confederation, an ...

, Duchy of Saxe-Gotha

Saxe-Gotha (german: Sachsen-Gotha) was one of the Saxon duchies held by the Ernestine branch of the Wettin dynasty in the former Landgraviate of Thuringia. The ducal residence was erected at Gotha.

History

The duchy was established in 1640, wh ...

, Duchy of Anhalt-Bernburg, Duchy of Anhalt-Dessau

Anhalt-Dessau was a principality of the Holy Roman Empire and later a duchy of the German Confederation. Ruled by the House of Ascania, it was created in 1396 following the partition of the Principality of Anhalt-Zerbst, and finally merged into t ...

, Duchy of Anhalt-Kothen, Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt

Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt was a small historic state in present-day Thuringia, Germany, with its capital at Rudolstadt.

History

Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt was established in 1599 in the course of a resettlement of Schwarzburg dynasty lands. Since t ...

, Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen

Schwarzburg-Sondershausen was a small principality in Germany, in the present day state of Thuringia, with its capital at Sondershausen.

History

Schwarzburg-Sondershausen was a county until 1697. In that year, it became a principality, which la ...

, Principality of Waldeck (state)

The County of Waldeck (later the Principality of Waldeck and Principality of Waldeck and Pyrmont) was a state of the Holy Roman Empire and its successors from the late 12th century until 1929. In 1349 the county gained Imperial immediacy and in 1 ...

, Principality of Lippe and the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe

Schaumburg-Lippe, also Lippe-Schaumburg, was created as a county in 1647, became a principality in 1807, a free state in 1918, and was until 1946 a small state in Germany, located in the present day state of Lower Saxony, with its capital at Bück ...

.

Fearing that Napoleon was going to strike him first, Blücher ordered this army to march north to join the rest of his own army.. The Prussian General Friedrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf

Friedrich Emil Ferdinand Heinrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf (9 April 1762 – 17 February 1823), born and died in Berlin, was a Prussian field marshal and a member of the old ' family von Kleist.

Biography

Kleist entered the Prussian Army in 1 ...

initially commanded this army before he fell ill on 18 June and was replaced by the Hessen-Kassel General Von Engelhardt. Its composition in June was:

* Hessen-Kassel Division (Three Hessian Brigades)- General Engelhardt

* Thuringian Brigade – Colonel Egloffstein

* Mecklenburg Brigade – General Prince of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

Total 25,000Chandler 1981, p. 30.

Prussian Reserve Army

Besides the four Army Corps that fought in theWaterloo Campaign

The Waterloo campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North and two Seventh Coalition armies, an Anglo-allied army and a Prussian army. Initially the French army was commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte, but he l ...

listed above that Blücher took with him into the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Prussia also had a reserve army stationed at home in order to defend its borders.

This consisted of:

* V Army Corps – Commanded by General Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg

Johann David Ludwig Graf Yorck von Wartenburg (born von Yorck; 26 September 1759 – 4 October 1830) was a Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' instrumental in the switching of the Kingdom of Prussia from a French alliance to a Russian allianc ...

* VI Army Corps – Commanded by General Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel von Tauentzien

* Royal Guard (VIII Corps) – Commanded by General Charles II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Organisation of the Royal Prussian Army

Staff system

The Prussian General Quartermaster Staff (General-Quartiermeister-Stab) was initially established byFrederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

in 1803. It was divided into three departments each corresponding with parts of the state. The Eastern brigade covering the territory east of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, the Western Brigade covering the territory west of the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

and the Southern Brigade covering the south of the kingdom. It was headed by a General Quartermaster (General-Quartiermeister) while a Lieutenant (General-Quartiermeister-Lieutenant) headed each brigade. This lasted until 1807 when the three brigades were merged.

During peacetime they were to develop operational plans for defensive and offensive actions in any potential campaign. They were also to produce detailed maps. From 1808 they studied recent campaigns and considered potential future scenarios. In 1810 Frederick William decreed that staff officers serve with different branches so as to gain practical knowledge of soldiering. On mobilisation staff officers would then be distributed among the personal staff of generals in various commands.

Otto Von Bismarck generals

Army General Headquarters

Ranks of the Prussian Army

This chart shows the line Infantry, cavalry, and light Infantry ranking system for the Royal Prussian Army of 1808 onward. General der Infanterie & its equivalent, General der Cavallerie, were unused, however still official, from 1808 until December 1813. Do note that these ranks are in the contemporary German used by the Prussians, not modern German. ::::::: The König could also serve as a military commander.Organization of Army

Royal Guard

As of 1813, the Royal Prussian Army's Royal Guard consisted of the following regiments: The following regiments were raised after Napoleon's exile in 1815, with the exception of the 2 grenadier regiments which were created in 1814 as a result of merging the provincial grenadier battalions:Uniforms

Royal Prussian Army uniforms consisted of a variety of colors. The Regimental colors determined the colors of one's facing color (collar, cuffs, lapels before 1809) and button color.See also

* Military history of Germany * Prussian Army#Napoleonic eraNotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *{{cite book, ref=none , last=Walter , first=Dierk , year=2003 , title=Preussische Heeresreformen 1807–1870: Militärische Innovation und der Mythos der "Roonschen Reform" , location=Paderborn , publisher=Schöningh , oclc=249071210 — dissertation of the University of Bern (2001) Armies of Napoleonic Wars