The Red Orchestra (german: Die Rote Kapelle, ), as it was known in Germany, was the name given by the

Abwehr Section III.F to

anti-Nazi resistance

Resistance movements during World War II occurred in every occupied country by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation to propaganda, hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. In many countries, r ...

workers in August 1941. It primarily referred to a loose network of resistance groups, connected through personal contacts, uniting hundreds of opponents of the

Nazi regime

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. These included groups of friends who held discussions that were centred on

Harro Schulze-Boysen

Heinz Harro Max Wilhelm Georg Schulze-Boysen (; Schulze, 2 September 1909 – 22 December 1942) was a left-wing German publicist and Luftwaffe officer during World War II. As a young man, Schulze-Boysen grew up in prosperous family with two sibli ...

,

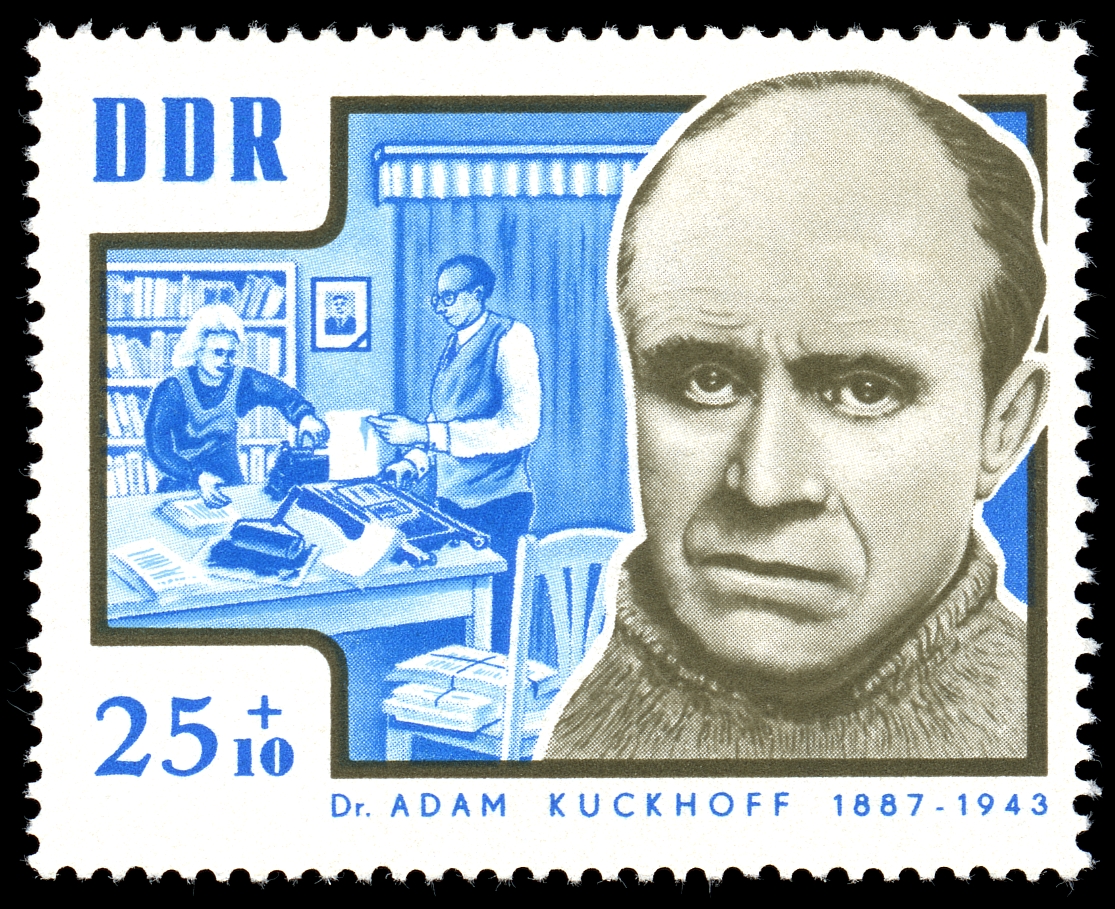

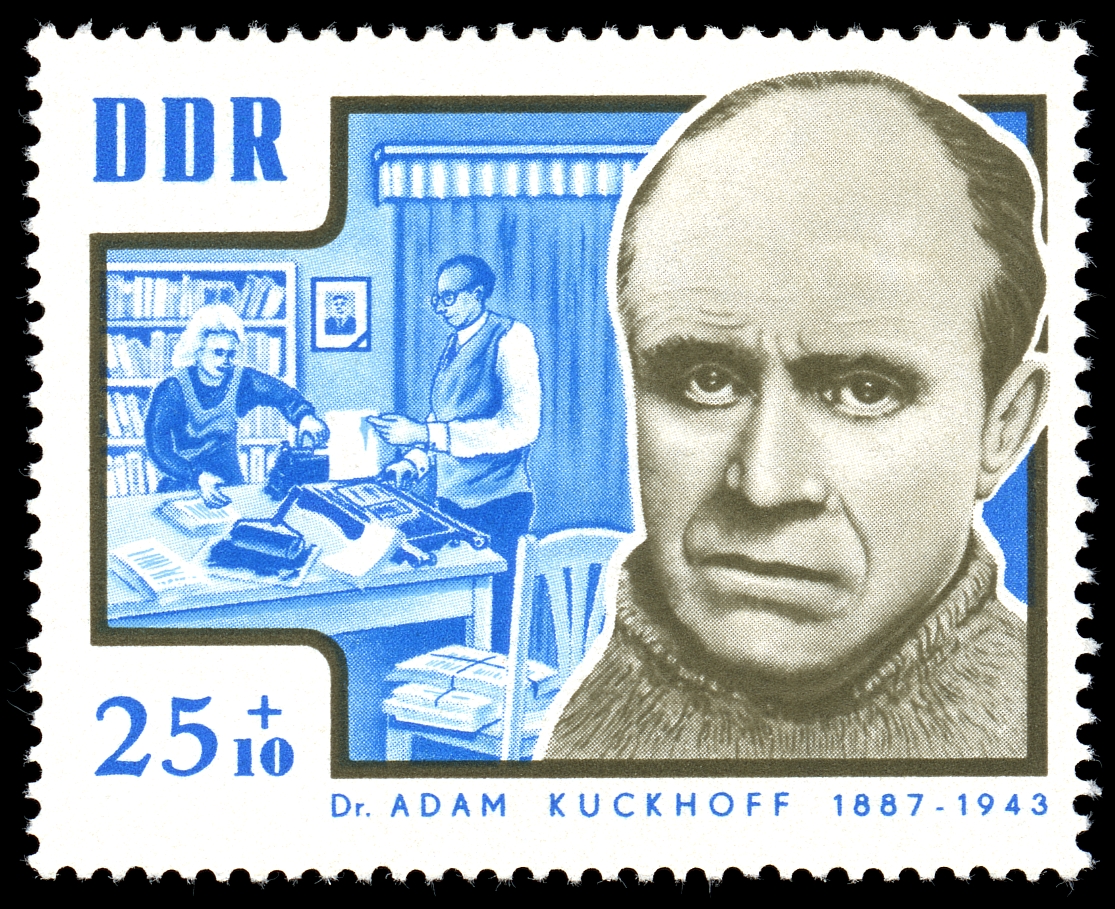

Adam Kuckhoff and

Arvid Harnack in Berlin, alongside many others. They printed and distributed prohibited leaflets, posters, and stickers, hoping to incite civil disobedience. They aided Jews and resistance to escape the regime, documented the atrocities of the Nazis, and transmitted military intelligence to the Allies. Contrary to legend, the Red Orchestra was neither directed by

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

communists nor under a single leadership. It was a network of groups and individuals, often operating independently. To date, about

400 members are known by name.

The term was also used by the German

Abwehr to refer to associated Soviet intelligence networks, working in Belgium, France, United Kingdom and the low countries, that were built up by

Leopold Trepper

Leopold Zakharovich Trepper (23 February 1904 – 10 January 1982) was a Polish Communist and career Soviet agent of the Red Army Intelligence. With the code name Otto'','' Trepper had worked with the Red Army since 1930. He was also a resistance ...

on behalf of the

Main Directorate of State Security (GRU). Trepper ran a series of

clandestine cells for organising agents. He used the latest technology, in the form of small wireless radios, to communicate with Soviet intelligence.

Although the monitoring of the radios' transmissions by the

Funkabwehr

Funkabwehr, or ''Radio Defense Corps'' was a radio counterintelligence organization created in 1940 by Hans Kopp of the German Nazi Party High Command during World War II. It acted as the principal organization for radio Counterintelligence, i.e ...

would eventually lead to the organisation's destruction, the sophisticated use of the technology enabled the organisation to behave as a network, with the ability to achieve tactical surprise and deliver high-quality intelligence, including the warning of

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

.

To this day, the German public perception of the "Red Orchestra" is characterised by the vested interest in historical revisionism of the post-war years and propaganda efforts of both sides of the

Cold War.

Reappraisal

For a long time after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, only parts of the German resistance to

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

had been known to the public within Germany and the world at large. This included the groups that took part in the

20 July plot and the

White Rose

The White Rose (german: Weiße Rose, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students (and one professor) at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, ...

resistance groups. In the 1970s there was a growing interest in the various forms of resistance and opposition. However, no organisations' history was so subject to systematic misinformation, and as little recognised, as those resistance groups centred on

Arvid Harnack and

Harro Schulze-Boysen

Heinz Harro Max Wilhelm Georg Schulze-Boysen (; Schulze, 2 September 1909 – 22 December 1942) was a left-wing German publicist and Luftwaffe officer during World War II. As a young man, Schulze-Boysen grew up in prosperous family with two sibli ...

.

In a number of publications, the groups that these two people represented were seen as traitors and spies. An example of these was ''Kennwort: Direktor; die Geschichte der Roten Kapelle'' (''Password: Director; The history of the Red Orchestra'') written by

Heinz Höhne

Heinz Höhne (1926 Berlin, Germany - 27 March 2010 in Großhansdorf) was a German journalist who specialized in Nazi and intelligence history.

Biography

Born in Berlin in 1926, Höhne was educated there until he was called to fight during the ...

who was a

Der Spiegel journalist. Höhne based his book on the investigation by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office against the General Judge of the

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

and Nazi apologist

Manfred Roeder who was involved in the Harnack and Schulze-Boysen cases during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and who contributed decisively to the formation of the legend that survived for much of the

Cold War period. In his book Höhne reports from former

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

and

Reich war court individuals who had a conflict of interest and were intent on defaming the groups attached to Harnack and Schulze-Boysen with accusations of treason.

The perpetuation of the defamation from the 1940s through to the 1970s that started with the Gestapo was incorporated by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office and evaluated as a journalistic process that can be seen by the 1968 trial of Nazi judge turned far-right Holocaust denier Manfred Roeder by the German lawyer

Robert Kempner

Robert Max Wasilii Kempner (17 October 1899 – 15 August 1993) was a German lawyer who played a prominent role during the Weimar Republic and who later served as assistant U.S. chief counsel during the International Military Tribunal at Nurembe ...

. The Frankfurt public prosecutor's office, which prosecuted the case against Roeder, based its investigation on procedure case number "1 Js 16/49" which was the trial case number defined by the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor's Office. The whole process propagated the Gestapo ideas of the Red Orchestra and this was promulgated in the report of the public prosecutor's office which stated:

In the course of time, a group of political supporters of different characters and backgrounds gathered around these two men and their wives. They were united in their active opposition to National Socialism and in their support for communism (emphasis added by the author). Until the outbreak of war with the Soviet Union, the focus of their work was on domestic policy. After that, it shifted more to the field of treason and espionage in favour of the Soviet Union. At the beginning of 1942, the Schulze-Boysen group was finally integrated into the widely ramified network of Soviet intelligence in Western Europe. The value of the intelligence passed on by the Schulze-Boysen group to the Soviet intelligence service cannot be underestimated according to general judgement. All persons who had to deal with this material in their official capacity agree that it was the most dangerous treason organisation uncovered during World War II.... In no... case, however, it is certain that those convicted were only sentenced for high treason and favouring the enemy. The Schulze-Boysen group was first and foremost a spy organisation for the Soviet Union. Since the outbreak of war with Russia, internal resistance took a back seat to espionage work, and it can be assumed that all members were used directly or indirectly for intelligence gathering.

From the perspective of the

German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(GDR) the Red Orchestra were honoured as anti-fascist resistance fighters and indeed received posthumous orders in 1969. However, the most comprehensive collection of biographies that exist are from the GDR, by Karl Heinz Biernat and

Luise Kraushaar

Luise Kraushaar ( Szepansky; 13 February 1905 – 10 January 1989) was a German political activist who became a Resistance campaigner against National Socialism and who also, after she left Germany, worked in the French Resistance. She later beca ...

''Die Schulze- Boysen- Harnack- Organisation im antifaschistischen Kampf'' (2002) and they represent their point of view, through the lens of ideology.

In the 1980s, the GDR historian

Heinrich Scheel, who at the time was vice president of the

East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

Academy of Sciences

An academy of sciences is a type of learned society or academy (as special scientific institution) dedicated to sciences that may or may not be state funded. Some state funded academies are tuned into national or royal (in case of the Unit ...

and who was part of the anti-Nazi Tegeler group (named after the area they met in, in Berlin) that included

Hans Coppi from 1933, conducted research into the Rote Kapelle and produced a paper which took a more nuanced view of the Rote Kapelle and discovered the work that was done to defame them. Scheel's work led to a re-evaluation of the Rote Kapelle, but it was not until 2009 that the German

Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Common ...

overturned the judgments of the National Socialist judiciary for "treason" and rehabilitated the members of the group.

Name

The name ''Rote Kapelle'' was a cryptonym that was invented for a secret operation started by Abwehrstelle Belgium (Ast Belgium), a field office of

Abwehr III.F in August 1941 and conducted against a Soviet intelligence station that had been detected in Brussels in June 1941. ''Kapelle'' was an accepted Abwehr term for counter-espionage operations against secret wireless transmitting stations and in the case of the Brussels stations ''Rote'' was used to differentiate from other enterprises conducted by Ast Belgium.

In July 1942, the case of the ''Red Orchestra'' was taken over from Ast Belgium by section IV. A.2. of the

Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

. When Soviet agent

Anatoly Gurevich

Anatoly Markovich Gurevich (russian: Анатолий Маркович Гуревич; 7 November 1913 – 2 January 2009) was a Soviet intelligence officer. He was an officer in the GRU operating as "разведчик-нелегал" (''razve ...

was arrested in November 1942, a small independent unit made up of Gestapo personnel known as the

Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle was formed in Paris in the same month and led by SS-Obersturmbannführer (Colonel)

Friedrich Panzinger

Friedrich Panzinger (1 February 1903 – 8 August 1959) was a German SS officer during the Nazi era. He served as the head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) Amt IV A, from September 1943 to May 1944 and the commanding officer of three sub ...

.

The

Reichssicherheitshauptamt

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and ''Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

(RSHA), the counter-espionage part of the

Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe duri ...

(SS), referred to resistance radio operators as "pianists", their transmitters as "pianos", and their supervisors as "conductors".

Only after the

funkabwehr

Funkabwehr, or ''Radio Defense Corps'' was a radio counterintelligence organization created in 1940 by Hans Kopp of the German Nazi Party High Command during World War II. It acted as the principal organization for radio Counterintelligence, i.e ...

had decrypted radio messages in August 1942, in which German names appeared, did the Gestapo start to arrest and imprison them, their friends and relatives. In 2002, the German filmmaker

Stefan Roloff, whose father

Helmut Roloff was a member of one of the Red Orchestra groups, stated of them:

::''Because of their contact with the Soviets, the Brussels and Berlin groups were grouped together by the Counterintelligence and Gestapo, under the misleading name of the Rote Kapelle. A

radio operator

A radio operator (also, formerly, wireless operator in British and Commonwealth English) is a person who is responsible for the operations of a radio system. The profession of radio operator has become largely obsolete with the automation of ra ...

who tapped

Morse code characters with his fingers was a pianist in the secret service language. A group of "pianists" formed a "band", and since the Morse code had come from

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, the "orchestra" was communist and therefore red. This misunderstanding laid the foundation on which the resistance group would later be treated as a Soviet espionage organisation, until this could be corrected in the early 1990s. The construct of a Red Orchestra organization, created by the Gestapo never existed as such''

In his research, the historian

Hans Coppi Jr., whose father was also a member,

Hans Coppi, emphasised that, in view of the Western European groups:

:''..a 'Red Orchestra' network in Western Europe, led by Leopold Trepper did not exist. The various groups in Belgium, Holland and France worked largely independently of one another.''

The German

political scientist

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

Johannes Tuchel summed up in a research article for the

Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand.

:''The Gestapo identifies it under the collective name "Red Orchestra" and wants it to be viewed above all as an espionage organization of the Soviet Union. This designation, which reduces the groups around Harnack and Schulze-Boysen to contacts with the Soviet intelligence service, continues to shape the public image in Germany also after 1945, distorting their motives and goals, even after 1945. At the end of 1942, the Reich Court Martial passes the first death sentences; in total, more than fifty members of this group are murdered. ''

Germany

Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group

The Red Orchestra, as historically viewed in the world today, are mainly the resistance groups around the

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

officer

Harro Schulze-Boysen

Heinz Harro Max Wilhelm Georg Schulze-Boysen (; Schulze, 2 September 1909 – 22 December 1942) was a left-wing German publicist and Luftwaffe officer during World War II. As a young man, Schulze-Boysen grew up in prosperous family with two sibli ...

, the writer

Adam Kuckhoff and the economist

Arvid Harnack, to which historians assign more than 100 people.

Origin

Harnack and Schulze-Boysen had similar political views, both rejected the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

of 1919, and sought alternatives to the existing social order. Since the

Great Depression of 1929, they saw the Soviet

planned economy as a positive counter-model to the

free-market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

economy. They wanted to introduce planned economic elements in Germany and work closely with the Soviet Union without breaking German bridges to the rest of Europe.

Before 1933, Schulze-Boysen published the non-partisan leftist and later banned magazine german: Gegner, lit=opponent. In April 1933, the

Sturmabteilung detained him for some time, severely battered him, and killed a fellow Jewish inmate. As a trained pilot, he received a position of trust in 1934 in the

Reich Ministry of Aviation

The Ministry of Aviation (german: Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) was a government department during the period of Nazi Germany (1933–45). It is also the original name of the Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus building on the Wilhelmstrasse ...

and had access to war-important information. After his marriage to

Libertas Schulze-Boysen

Libertas "Libs" Schulze-Boysen, born Libertas Viktoria Haas-Heye (20 November 1913 in Paris – 22 December 1942 in Plötzensee Prison ) was a German aristocrat and resistance fighter against the Nazis. From the early 1930s to 1940, Libs attem ...

in 1936, the couple collected young intellectuals from diverse backgrounds, including the artist couple

Kurt and

Elisabeth Schumacher, the writers

Günther Weisenborn and

Walter Küchenmeister, the

photojournalist John Graudenz (who had been expelled from the USSR for reporting the

Soviet famine of 1932–1933

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

) and

Gisela von Pöllnitz, the actor

Marta Husemann

Marta Husemann ( Wolter, later Jendretzky; 20 August 1913 – 30 June 1960) was a German actress and German resistance to Nazism, anti-Nazi Resistance fighter in the Red Orchestra (espionage), Red Orchestra.

Life

Husemann trained as a tailor ...

and her husband Walter in 1938, the doctors

Elfriede Paul

Elfriede Paul (14 January 1900 – 30 August 1981) was a German physician and resistance fighter against the Nazi regime. Paul, a small and energetic woman, was a communist member of the anti-fascist resistance group that was later called the ...

in 1937 and

John Rittmeister in Christmas 1941, the dancer

Oda Schottmüller, and since Schulze-Boysen held twice-monthly meetings at his

Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Prussia, it is best known for Charlottenburg Palace, the ...

atelier

An atelier () is the private workshop or studio of a professional artist in the fine or decorative arts or an architect, where a principal master and a number of assistants, students, and apprentices can work together producing fine art or ...

for thirty-five to forty people in what was considered a

Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

circle of friends. Initially, these meetings followed an informatics program of resistance that was in keeping with its environment and were important places of personal and political understanding but also vanishing points from an often unbearable reality, essentially serving as ''islands of democracy''. As the decade progressed they increasingly served as identity-preserving forms of self-assertion and cohesion as the Nazi state became all-encompassing. Formats of the meetings usually started with book discussions in the first 90 minutes were followed by Marxist discussions and resistance activities that were interspersed with parties, picnics, sailing on the

Wannsee

Wannsee () is a locality in the southwestern Berlin borough of Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Germany. It is the westernmost locality of Berlin. In the quarter there are two lakes, the larger ''Großer Wannsee'' (Greater Wannsee, "See" means lake) and the ...

and poetry readings until midnight as the mood took. However, as the realisation that the war preparations were becoming unstoppable and the future victors were not going to be the Sturmabteilung, Schulze-Boysen whose decisions were in demand called for the group to cease their discussions and start resisting.

Other friends were found by Schulze-Boysen among former students of a reform school on the island of Scharfenberg in

Berlin-Tegel. These often came from communist or social - democratic workers' families, e.g. Hans and

Hilde Coppi,

Heinrich Scheel, Hermann Natterodt and Hans Lautenschlager. Some of these contacts existed before 1933, for example through the German ''Society of intellectuals''. John Rittmeister's wife Eva was a good friend of

Liane Berkowitz,

Ursula Goetze,

Friedrich Rehmer,

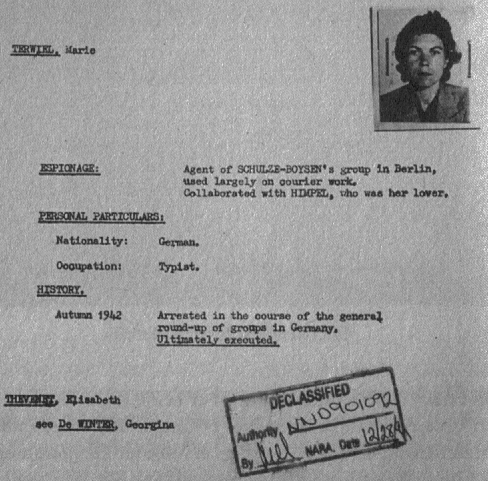

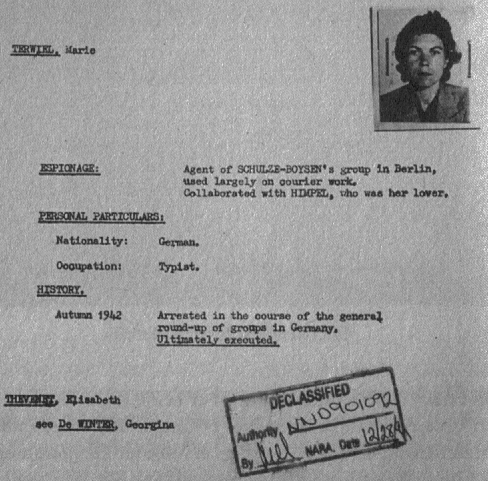

Maria Terwiel and

Fritz Thiel who met in the 1939

abitur class at the secondary private school, ''Heil'schen Abendschule'' at Berlin W 50, Augsburger Straße 60 in

Schöneberg

Schöneberg () is a locality of Berlin, Germany. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a separate borough including the locality of Friedenau. Together with the former borough of Tempelhof it is now part of the new borough of Tempe ...

. The Romanist

Werner Krauss

Werner Johannes Krauss (''Krauß'' in German; 23 June 1884 – 20 October 1959) was a German stage and film actor. Krauss dominated the German stage of the early 20th century. However, his participation in the antisemitic propaganda film ''Jud S ...

joined this group, and through discussions, an active resistance to the Nazi regime grew.

Ursula Goetze who was part of the group, provided contacts with the communist groups in

Neukölln.

From 1932 onwards, the

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

Arvid Harnack and his American wife

Mildred assembled a group of friends and members of the Berlin

Marxist Workers School (MASCH) to form a discussion group that debated the political and economic perspectives at the time. Harnak's group meetings, in contrast to those of Schulze-Boysen's group, were considered rather austere. Members of the group included the German politician and Minister of Culture

Adolf Grimme

Adolf Berthold Ludwig Grimme (31 December 1889 – 27 August 1963) was a German politician, a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He was Cultural Minister during the later years of the Weimar Republic and after World War II, during the ...

, the locksmith

Karl Behrens, the German journalist

Adam Kuckhoff and his wife Greta and the industrialist and entrepreneur Leo Skrzypczynski. From 1935, Harnack tried to camouflage his activities by becoming a member of the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

working in the Reich Ministry of Economics with the rank of Oberregierungsrat. Through this work, Harnack planned to train them to build a free and socially just Germany after the end of the

National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

' regime.

The dancer

Oda Schottmüller and

Erika Gräfin von Brockdorff were friends with the Kuckhoffs. In 1937 Adam Kuckhoff introduced Harnack to the journalist and former journalist railway worker

John Sieg, a former editor of the

Communist Party of Germany (KPD) newspaper the

Die Rote Fahne

''Die Rote Fahne'' (, ''The Red Flag'') was a German newspaper originally founded in 1876 by Socialist Worker's party leader Wilhelm Hasselmann, and which has been since published on and off, at times underground, by German Socialists and Communi ...

. As a railway worker at the

Deutsche Reichsbahn

The ''Deutsche Reichsbahn'', also known as the German National Railway, the German State Railway, German Reich Railway, and the German Imperial Railway, was the German national railway system created after the end of World War I from the regiona ...

, Sieg was able to make use of work-related travel, enabling him to found a communist resistance group in the

Neukölln borough in Berlin. He knew the former Foreign Affairs Minister

Wilhelm Guddorf and

Martin Weise. In 1934 Guddorf was arrested and sentenced to hard labour. In 1939 after his release from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Guddorf worked as a bookseller, and worked closely with Schulze-Boysen.

Through such contacts, a loose network formed in Berlin in 1940 and 1941, of seven interconnected groups centred on personal friendships as well as groups originally formed for discussion and education. This disparate network was composed of over 150 Berlin Nazi opponents, including artists, scientists, citizens, workers, and students from several different backgrounds. There were

Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, political conservatives,

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

,

Catholics, and

atheists

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

. Their ages ranged from 16 to 86, and about 40% of the group were women. Group members had different political views, but searched for the open exchange of views, at least in the private sector. For instance, Schulze-Boysen and Harnack shared some ideas with the Communist Party of Germany, while others were devout Catholics such as

Maria Terwiel and her husband

Helmut Himpel. Uniting all of them was the firm rejection of national socialism.

This network grew up after Adam and Greta Kuckhoff introduced Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen to Arvid and Mildred Harnack, and the couples began engaging socially. Their hitherto separate groups moved together once the

Polish campaign

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

began in September 1939. From 1940 onwards, they regularly exchanged their opinions on the war and other Nazi policies and sought action against it.

The historian Heinrich Scheel, a schoolmate of Hans Coppi, judged these groups by stating:

:'' Only with this stable hinterland was it possible to survive all the minor mishaps and major catastrophes and give our resistance permanence.''

As early as 1934, Scheel had passed written material from one contact person to the next within clandestine communist

cells and had seen how easily such connections were lost if a meeting did not materialise due to one party being arrested. In a relaxed group of friends and discussion with like-minded people, it was easy to find supporters for an action.

Acts of resistance

From 1933 onwards, the Berlin groups connected to Schulze-Boysen and Harnack resisted the Nazis by:

* Providing assistance to the persecuted.

* Disseminating pamphlets and leaflets that contained dissident content.

* Writing letters to prominent individuals including university professors.

* Collecting and sharing information, including on foreign representatives, on German war preparations, crimes of the Wehrmacht and Nazi crimes.

* Contacting other opposition groups and foreign forced labourers.

* Invoking disobedience of Nazi representatives.

* Writing drafts for a possible post-war order.

From mid-1936, the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

preoccupied the Schulze-Boysen group. Through Walter Küchenmeister, the Schulze-Boysen group began to discuss more concrete actions, and during these meetings would listen to foreign radio stations from London, Paris and Moscow. A plan was formed to take advantage of Schulze-Boysen's employment, and through this, the group was able to get detailed information on Germany's support of

Francisco Franco. Beginning in 1937, in the

Wilmersdorf

Wilmersdorf (), an inner-city locality of Berlin, lies south-west of the central city. Formerly a borough by itself, Wilmersdorf became part of the new borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf in Berlin's 2001 administrative reform.

History

The v ...

waiting room of Dr. Elfriede Paul, they began distributing the first leaflet on the Spanish Civil War.

In the same year, Schulze-Boysen had compiled a document about a sabotage enterprise planned in Barcelona by the Wehrmacht "Special Staff W", an organisation established by

Helmuth Wilberg

Helmuth Wilberg (1 June 1880 – 20 November 1941) was a German officer of Jewish ancestry and a ''Luftwaffe'' General of the Air Force during the Second World War.

Military career

Wilberg joined the 80. Fusilier Regiment "von Gersdorff" (''K ...

to analyse the tactical lessons learned by the

''Legion Kondor'' during the war. The information that Schulze-Boysen collected included details about German transports, deployment of units and companies involved in the German defense. Libertas's cousin,

Gisela von Pöllnitz placed the letter in the mailbox of the Soviet Embassy on the

Bois de Boulogne

The Bois de Boulogne (, "Boulogne woodland") is a large public park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine. The land was ceded to the city of Paris by t ...

in Paris.

After the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, Schulze-Boysen created a second leaflet with Walter Küchenmeister, that declared the annexation of the

Sudetenland in October 1938 as a further step on the way to a new world war. This leaflet was called ''Der Stoßtrupp'' or ''The Raiding Patrol'', and condemned the Nazi government and argued against the government's propaganda. A document that was used at the trial of Schulze-Boysen indicated that only 40 to 50 copies of the leaflet were distributed.

Call for popular uprising

AGIS leaflets

From 1942 onwards, the group started to produce leaflets that were signed with ''AGIS'' in reference to the

Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

n King

Agis IV, who fought against corruption for his people. Naming the newspaper ''Agis'', was originally the idea of

John Rittmeister. The pamphlets had titles like, ''The becoming of the Nazi movement'', ''Call for opposition'', ''Freedom and violence'' and ''Appeal to All Callings and Organisations to resist the government''. The writing of the AGIS leaflet series was a mix of Schulze-Boysen and

Walter Küchenmeister, a communist political writer, who would often include copy from KPD members and through contacts.

They were often left in phone booths or selected addresses from the phone book. Extensive precautions were taken, including wearing gloves, using many different

typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectivel ...

s and destroying the

carbon paper

Carbon paper (originally carbonic paper) consists of sheets of paper which create one or more copies simultaneously with the creation of an original document when inscribed by a typewriter or ballpoint pen.

History

In 1801, Pellegrino Turri, ...

.

John Graudenz also produced, running duplicate

mimeograph

A mimeograph machine (often abbreviated to mimeo, sometimes called a stencil duplicator) is a low-cost duplicating machine that works by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper. The process is called mimeography, and a copy made by the proc ...

machines in the apartment of

Anna Krauss

Anna Krauss ( Friese; 27 October 1884, Bogen – 5 August 1943, Plötzensee Prison, Berlin) was a German clairvoyant, fortune-teller and businesswomen who owned a lacquer and paint wholesaler business in Berlin. She became a resistance fight ...

.

On 15 February 1942, the group wrote the large 6-page pamphlet called ''Die Sorge Um Deutschlands Zukunft geht durch das Volk!'' (''Anxiety about Germany's future is moving through the people!''). The master copy was arranged by the

potter Cato Bontjes van Beek and the pamphlet was written up by

Maria Terwiel on her typewriter, five copies at a time. The paper describes how the care of Germany's future is decided by the people... and called for the opposition to the war, the Nazis, all Germans who now threaten the future of all. A copy survives to the present day.

The text first analysed the current situation: contrary to the

Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

, most German armies were in retreat, the number of war dead was in the millions. Inflation, scarcity of goods, plant closures, labour agitation and corruption in State authorities were occurring all the time. Then the text examined German war crimes:

:''But the conscience of all true patriots rebels against the whole current form of German exercise of power in Europe. All who have retained their sense of genuine values see with a shudder how the good name of Germany is falling into disrepute under the swastika symbol. In all occupied countries today, hundreds, often thousands, of people are shot or hanged arbitrarily, without due process, people who can be accused of nothing other than of being loyal to their country

..In the name of the Reich the most hideous tortures and atrocities are committed against civilians and prisoners. Never yet in history has a man been so hated as Adolf Hitler. The hatred of tortured humanity burdens the entire German people''

=The Soviet Paradise exhibition

=

In May 1942,

Joseph Goebbels held a Nazi propaganda exhibition with the ironic name of

The Soviet Paradise

The Soviet Paradise (German original title "''Das Sowjet-Paradies''") was the name of an exhibition and a propaganda film created by the Department of Film of the propaganda organisation (''Reichspropagandaleitung'') of the German Nazi Party (NSDA ...

(German original title "Das Sowjet-Paradies") in

Lustgarten

The ' () is a park on Museum Island in central Berlin, near the site of the former () of which it was originally a part. At various times in its history, the park has been used as a parade ground, a place for mass rallies and a public park.

Th ...

, with the express purpose of justifying the invasion of the Soviet Union to the German people.

Both the Harnacks and Kuckhoffs spent half a day at the exhibition. For

Greta Kuckhoff particularly and her friends, the most distressing aspect of the exhibition was the installation about

SS measures against Russian "partisans" (

Soviet partisans

Soviet partisans were members of resistance movements that fought a guerrilla war against Axis forces during World War II in the Soviet Union, the previously Soviet-occupied territories of interwar Poland in 1941–45 and eastern Finland. The ...

). The exhibition contained images of firing squads and bodies of young girls, some still children, who had been hung and were dangling from ropes. The group decided to act. It was

Fritz Thiel and his wife Hannelore who printed stickers using a child's toy rubber stamp kit. In a campaign initiated by

John Graudenz on 17 May 1942, Schulze-Boysen, Marie Terwiel and nineteen others, mostly people from the group around Rittmeister, travelled across five Berlin neighbourhoods to paste the stickers over the original exhibition posters with the message:

: Permanent Exhibition

: The Nazi Paradise

: War, Hunger, Lies, Gestapo

: How much longer?

The Harnacks were dismayed at Schulze-Boysen's actions and decided not to participate in the exploit, believing it to be reckless and unnecessarily dangerous.

On 18 May,

Herbert Baum

Herbert Baum (February 10, 1912 – June 11, 1942) was a Jewish member of the German resistance against National Socialism.

Life

Baum was born in Moschin, Province of Posen; his family moved to Berlin when he was young. After he graduated fr ...

, a Jewish communist who had contact with the Schulze-Boysen group through

Walter Husemann, delivered incendiary bombs to the exhibition in the hope of destroying it. Although 11 people were injured, the whole episode was covered up by the government, and the action lead to the arrest of 250 Jews including Baum himself. Following the action, Harnack asked the Kuckoffs to revisit the exhibition to determine whether any damage had been done to it, but they found little damage was visible.

Acts of espionage

The

Invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

on 1 September 1939, was seen as the beginning of the feared world war, but also as an opportunity to eliminate Nazi rule and to invoke a thorough transformation of German society. Hitler's victories in France and Norway in 1940 encouraged them to expect the replacement of the Nazi regime, above all from the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, not from Western capitalism. They believed that the Soviet Union would keep Germany as a sovereign state after its victory and that they wanted to work towards a corresponding opposition without domination by the Communist Party of Germany.

Around 13 June 1941, Harro Schulze-Boysen prepared a report that gave the final details of the Soviet invasion including details of Hungarian airfields containing German planes. On 17 June, the

Soviet People's Commissar for State Security presented the report to Stalin, who harshly dismissed it as disinformation.

In December 1941,

John Sieg published ''The Internal Front'' (German:Die Innere Front) on a regular basis. It contained texts by Walter Husemann,

Fritz Lange, Martin Weise and , including information about the economic situation in Europe, references to Moscow radio frequencies, and calls for resistance. It was produced in several languages for foreign forced labourers in Germany. Only one copy from August 1942 has survived. After the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Hilde Coppi had secretly listened to Moscow radio in order to receive signs of life from German prisoners of war and to forward them to their relatives via Heinrich Scheel. This news contradicted the Nazi propaganda that the Red Army would murder all German soldiers who surrendered. In order to educate them about propaganda lies and Nazi crimes, the group copied and sent letters to soldiers on the Eastern Front, addressed to a fictitious police officer.

In autumn 1941 the eyewitness Erich Mirek reported to Walter Husemann about mass murders of Jews by the

SS and

SD in

Pinsk

Pinsk ( be, Пі́нск; russian: Пи́нск ; Polish: Pińsk; ) is a city located in the Brest Region of Belarus, in the Polesia region, at the confluence of the Pina River and the Pripyat River. The region was known as the Marsh of Pinsk ...

. The group announced these crimes in their letters.

The Berlin group undoubtedly provided valuable intelligence to the Soviet Union. However, a Soviet memo dated 25 November 1941 and recently discovered by

Shareen Blair Brysac, details the organisational problems in evaluating the intelligence. Reports were forwarded to

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

, who was unable to act on their contents, which resulted in the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

being unable to form a cogent response. Ultimately, the groups' efforts had no effect on Soviet military strategy.

The von Scheliha Group

The cavalry officer, diplomat and later resistance fighter

Rudolf von Scheliha was recruited by Soviet intelligence while in Warsaw in 1934. Although a member of the Nazi party since 1938, he took an increasingly critical stance against the Nazi regime by 1938 at the latest. He became an informant to journalist

Rudolf Herrnstadt. Intelligence from von Scheliha would be sent to Herrnstadt, via the

cutout Ilse Stöbe, who would then pass it to the Soviet embassy in Warsaw. In September 1939, Scheliha was appointed director of an ''information department'' in the Foreign Office, that was created to counter foreign press and radio news by creating propaganda about the German occupation policy in Poland. This necessitated a move back to Berlin, and Stöbe followed, attaining a position arranged by von Scheliha in the ''press section'' of the Foreign Office, that enabled her to pass documents from von Scheliha to a representative of

TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

.

Von Scheliha's position in the ''information department'' exposed him to reports and images of Nazi atrocities, enabling him to verify the veracity of foreign reports of Nazi officials. By 1941, von Scheliha had become increasingly dissatisfied with the Nazi regime and began to resist by collaborating with

Henning von Tresckow

Henning Hermann Karl Robert von Tresckow (; 10 January 1901 – 21 July 1944) was a German military officer with the rank of major general in the German Army who helped organize German resistance against Adolf Hitler. He attempted to assassina ...

. Scheliha secretly made a collection of documents on the atrocities of the Gestapo, and in particular, on murders of Jews in Poland, documents which also contained photographs of newly established extermination camps. He informed his friends first before later attempting to notify the Allies, including a trip to Switzerland with information on ''

Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post- war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address o ...

'' that was shared with Swiss diplomats. His later reports exposed the

Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

. After

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

severed Soviet lines of communication in Berlin, Soviet intelligence made attempts to reconnect with Von Scheliha in May 1942, but the effort failed.

Individuals and small groups

Other small groups and individuals, who knew little or nothing about each other, each resisted the National Socialists in their own way until the Gestapo arrested them and treated them as a common espionage organisation from 1942 to 1943.

* Kurt Gerstein

:

Kurt Gerstein

Kurt Gerstein (11 August 1905 – 25 July 1945) was a German SS officer and head of technical disinfection services of the ''Hygiene-Institut der Waffen-SS'' (Institute for Hygiene of the Waffen-SS). After witnessing mass murders in the Belzec a ...

was a German

SS officer who had twice been sent to concentration camps in 1938 due to close links with the

Confessional Church

Confessionalism, in a religious (and particularly Christian) sense, is a belief in the importance of full and unambiguous assent to the whole of a religious teaching. Confessionalists believe that differing interpretations or understandings, espe ...

and had been expelled from the Nazi Party. As a mine manager and industrialist, Gerstein was convinced that he could resist by exerting influence inside the Nazi administration. On 10 March 1941, when he heard about the German euthanasia program

Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post- war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address o ...

, he joined the SS. Assigned to the Hygiene-Institut der Waffen-SS (Institute for Hygiene of the Waffen-SS), he was ordered by the

RSHA to supply

prussic acid

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on an in ...

to the Nazis. Gerstein set about finding methods to dilute the acid, but his main aim was to report the euthanasia programme to his friends. In August 1942, after attending a gassing using a diesel engine exhaust from a car, he informed the Swedish embassy in Berlin of what happened.

* Willy Lehmann

:

Willy Lehmann was a communist sympathiser who was recruited by the Soviet

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

in 1929 and became one of their most valuable agents. In 1932 Lehmann joined the

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

and reported to the NKVD the complete work of the Gestapo. In 1935 Lehmann attended a rocket engine ground firing test in

Kummersdorf that was attended by

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

. From this Lehmann sent six pages of data to Stalin on 17 December 1935. Through Lehmann, Stalin also learned about the power struggles in the Nazi party, rearmament work and even the date of

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

. In October 1942 Lehmann was discovered by the Gestapo and murdered without trial. Lehmann had no connection to the Schulze-Boysen or Harnack group.

Belgium

The Trepper Group

Belgium was a favourite place for Soviet espionage to establish operations before

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

as it was geographically close to the centre of Europe, provided good commercial opportunities between Belgium and the rest of Europe and most important of all, the Belgian government was indifferent to foreign espionage operations that were conducted as long as they were against foreign powers and not Belgium itself. The first Soviet agents to arrive in Belgium were technicians. The

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

agent, communist agitator and radio specialist

Johann Wenzel

Johann Wenzel (9 March 1902, Nidowo, Nowy Staw – 2 February 1969, Berlin) was a German Communist, highly professional GRU agent and radio operator of the espionage group that was later called the Red Orchestra by the Abwehr in Belgium and th ...

arrived in January 1936, to establish a base. However, the Belgian authorities refused him permission to remain, so he moved to the Netherlands in early 1937, where he made contact with

Daniël Goulooze, who was director of the

Communist Party of the Netherlands

The Communist Party of the Netherlands ( nl, Communistische Partij Nederland, , CPN) was a Dutch communist party. The party was founded in 1909 as the Social-Democratic Party (SDP) and merged with the Pacifist Socialist Party, the Political Part ...

(CPN) and who acted as the main liaison officer between the CPN and the

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

in Moscow.

Leopold Trepper

Leopold Zakharovich Trepper (23 February 1904 – 10 January 1982) was a Polish Communist and career Soviet agent of the Red Army Intelligence. With the code name Otto'','' Trepper had worked with the Red Army since 1930. He was also a resistance ...

was an agent of the

Red Army Intelligence and had been working with Soviet intelligence since 1930. Trepper along with Soviet

military intelligence officer,

Richard Sorge

Richard Sorge (russian: Рихард Густавович Зорге, Rikhard Gustavovich Zorge; 4 October 1895 – 7 November 1944) was a German-Azerbaijani journalist and Soviet military intelligence officer who was active before and during Wo ...

were the two main Soviet agents in Europe and were employed as ''roving agents'' setting up espionage networks in Europe and Japan. Whereas Richard Sorge was a

penetration agent, Trepper ran a series of

clandestine cells for organising agents. Trepper used the latest technology, in the form of small wireless radios to communicate with Soviet intelligence. Although the monitoring of the radios transmissions by the

Funkabwehr

Funkabwehr, or ''Radio Defense Corps'' was a radio counterintelligence organization created in 1940 by Hans Kopp of the German Nazi Party High Command during World War II. It acted as the principal organization for radio Counterintelligence, i.e ...

would eventually lead to the organisations destruction, the sophisticated use of the technology-enabled the organisation to behave as a network.

During the 1930s, Trepper had worked to create a large pool of informal intelligence sources, through contacts with the

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

. In 1936, Trepper became the technical director of Soviet Red Army Intelligence in Western Europe. He was responsible for recruiting agents and creating espionage networks. During early 1938, he was sent to

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

to establish commercial cover for a spy network in France and the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. In the autumn of 1938, Trepper approached a Jewish businessman and former Comintern agent

Léon Grossvogel, whom he had known in Palestine. Grossvogel ran a small business called ''Le Roi du Caoutchouc'' or ''The Raincoat King'' on behalf of its owners. Trepper had a plan to use money that had been provided to him, to create a business that would be the export division of ''The Raincoat King''. The new business was given an unidiomatic name of

Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company. Trepper's plan was to wait until the company gained market share, and then when it was of sufficient size, infiltrate it with communist personal in positions such as shareholders, business managers and department heads. On 6 March 1939, Trepper, now using the alias ''Adam Mikler'', a wealthy Canadian businessman, moved, with his wife, to Brussels to make it his new base.

In March 1939, Trepper was joined by GRU agent

Mikhail Makarov posing as ''Carlos Alamo'', who was to provide expertise in forged documentation e.g. preparation of

Kennkarte The ''Kennkarte'' was the basic identity document in use inside Germany (including occupied incorporated territories) during the Third Reich era. They were first introduced in July 1938. They were normally obtained through a police precinct and bore ...

s. However, Grossvogel had recruited

Abraham Rajchmann, a criminal forger, to the group and thenceforth Makarov became a radio operator.

In July 1939, Trepper was joined in Brussels by GRU agent

Anatoly Gurevich

Anatoly Markovich Gurevich (russian: Анатолий Маркович Гуревич; 7 November 1913 – 2 January 2009) was a Soviet intelligence officer. He was an officer in the GRU operating as "разведчик-нелегал" (''razve ...

posing as the wealthy Uruguayan ''Vincente Sierra'' Gurevich has already completed his first operation by meeting Schulze-Boysen in order to reestablish him as an intelligence source and to arrange courier service. Gurevich's original remit was to learn the operation of the raincoat company and establish a new store in

Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

.

Wartime activity

At the start of the war, Trepper had to revise his plans significantly. After the

conquest of Belgium in May 1940, Trepper fled to Paris, leaving Gurevich responsible for the Belgium network. Gurevich, operating from a safehouse located at 101 Rue des Atrébates in Brussels, used Makarov as his wireless radio operator,

Sophia Poznańska as his cipher clerk,

Rita Arnould as a courier and housekeeper, and Isidor Springer, who worked as a courier between Gurevich and Trepper and as a recruiter. Gurevich's main task was to transmit reports received from Harro Schulze-Boysen and Trepper. In June 1941, Trepper sent Anton Danilov to assist Makarov with radio transmissions. In October 1941, Gurevich visited Germany, to reestablish communications with the Shulze-Boysen/Harnack group and then to deliver a cypher key to

Ilse Stöbe that was instead delivered to

Kurt Schulze. In September or October 1941, Trepper ordered Rajchmann to join Gurevich as the group's documentation expert. The last core member of the group was the courier,

Malvina Gruber. Gruber specialised in couriering people, often across borders. Her main role with the group was as a courier between Rajchmann and Trepper and as an assistant to Rajchmann.

On 13 December 1941, the apartment at Rue Des Atrebates was raided by the Abwehr. Gurevich was saved as Trepper warned him. All other members of the house were arrested.

The Jeffremov Group

This network was run by Soviet Army Captain

Konstantin Jeffremov. He arrived in Brussels in March 1939 to organise various groups into a network. Jeffremov's group was independent of Trepper's group, although there were some members who worked for both and it was likely that by 1941, Jeffremov knew about Gurevich's network.

Jeffremov's most important agent, was the Belgian Edouard Van der Zypen, who worked at

Henschel & Son

Henschel & Son (german: Henschel und Sohn) was a German company, located in Kassel, best known during the 20th century as a maker of transportation equipment, including locomotives, trucks, buses and trolleybuses, and armoured fighting vehic ...

, a manufacturing company in

Kassel that made aircraft and tanks. His other recruits were

Maurice Peper,

Elizabeth Depelsenaire. Peper was a professional radio operator who was recruited into the network in 1940 and became the main liaison between Belgium and Amsterdam. After the reorganisation, he worked as the cutout between Jeffremov and Rajchmann. Depelsenaire was responsible for her own sub-group, that provided safe accommodation in the Brussels area. Anton Winterink worked for Jeffremov for most of 1940 in Brussels but made frequent trips to the Netherlands where he established another network. Later in 1940, Jeffremov ordered Winterink to take charge of the network, that became known as group ''Hilda''. By December 1940, both Wenzel in Belgium and Winterink in the Netherlands had established a radio link with Moscow, that was being used to transmit intelligence provided by Jeffremov. In 1939, the married couple,

Franz Franz may refer to:

People

* Franz (given name)

* Franz (surname)

Places

* Franz (crater), a lunar crater

* Franz, Ontario, a railway junction and unorganized town in Canada

* Franz Lake, in the state of Washington, United States – see ...

and

Germaine Schneider were recruited by Jeffremov. The couple were members of the

Communist Party of Belgium

french: Parti Communiste de Belgique

, abbreviation = KPB-PCB

, colorcode =

, leader1_title = Historical leaders

, leader1_name = Joseph JacquemotteJulien LahautLouis Van Geyt

, founder = Julien Lahaut

, founded =

, dissolved =

, merge ...

and had been running

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

(Comintern)

safe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is, in a generic sense, a secret place for sanctuary or suitable to hide people from the law, hostile actors or actions, or from retribution, threats or perceived danger. It may also be a metaphor.

Histori ...

s in Brussels. For a number of years Germaine Schneider was the most important of the two, working as a courier from 1939 to 1942 that involved extensive travel across the Low Countries. Before the war, she was

Henry Robinson's contact to Soviet agents in

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

. While she worked from Jeffremov, she couriered between Brussels and Paris.

In May 1942, as part of a reorganisation effort after the raid on the Rue des Atrebates safehouse, Trepper met Jeffremov in Brussels to instruct him to take over the running of the Belgian espionage network in the absence of

Anatoly Gurevich

Anatoly Markovich Gurevich (russian: Анатолий Маркович Гуревич; 7 November 1913 – 2 January 2009) was a Soviet intelligence officer. He was an officer in the GRU operating as "разведчик-нелегал" (''razve ...

who had run the network from July 1940 to December 1941. The most important aspect of Jeffremov's new commission was to ensure the continued transmission of the intelligence they were receiving from the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group. This information was forwarded to Soviet intelligence via a

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

radio transmitter. Jeffremov was frequently admonished by Soviet intelligence for his lack of activity and slow production of quality intelligence. In May 1942, following Makarov's arrest, Wenzel agreed to begin transmitting for Jeffremov and operated out of a safehouse at 12 Rue de Namur in Brussels.

On 30 July 1942, the house at 12 Rue de Namur was raided by the Abwehr and Wenzel was arrested. Germaine Schneider managed to warn Trepper, who warned Jeffremov, who managed to escape.

Netherlands

Dutch Information Service

In 1935, Dutch Comintern member

Daniël Goulooze established the clandestine ''Dutch Information Service'' (DIS), an intelligence organisation to collect information for consumption by Soviet intelligence. In 1937, Goulooze was sent for intelligence training to the Soviet Union. When he returned, he became the main

rezident A resident spy in the world of espionage is an agent operating within a foreign country for extended periods of time. A base of operations within a foreign country with which a resident spy may liaise is known as a "station" in English and a (, 're ...

() agent for the Netherlands. In the years leading up to the war, Goulooze had contacts with the KPD officials in Berlin and Comintern members in the Low Countries, France and Great Britain. In 1937, Goulooze established a wireless telegraphy connection between the Comintern in Amsterdam and the Soviet Union.

In October 1937,

Johann Wenzel

Johann Wenzel (9 March 1902, Nidowo, Nowy Staw – 2 February 1969, Berlin) was a German Communist, highly professional GRU agent and radio operator of the espionage group that was later called the Red Orchestra by the Abwehr in Belgium and th ...

contacted Goulooze in Amsterdam and they discussed plans for the construction of a radio network in Belgium. At the end of 1938, Wenzel again visited Goulooze, to recruit Dutch national and

Rote Hilfe

The Rote Hilfe ("Red Aid") was the German affiliate of the International Red Aid. The Rote Hilfe was affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany and existed between 1924 and 1936. Its purpose was to provide help to those Communists who had be ...

member

Anton Winterink. By September 1939, Wenzel had trained Winterink as a radio operator, in Brussels. Winterink subsequently became the radio operator for the Jeffremov group in Belgium. In the lead up to the war, Wenzel continued to recruit Dutch communists from Goulooze, for the Jeffremov group. In October 1939, Gurevich visited Goulooze to request help to build his espionage network in Belgium. Gurevich asked that a temporary wireless telegraphy link be established for his use, while he established his own wireless telegraphy link. This was used until January 1940.

As the war progressed and the other communist organisations were destroyed, the DIS became increasingly important to Soviet intelligence as the only organisation in Western Europe that could maintain contact with Soviet agents on the ground. Such was the level of communication Goulooze conducted with Soviet intelligence, that he maintained four separate and active

wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

sets and one in reserve.

Knöchel Emigre group

In 1940, it was decided by the Comintern that various KPD sections (Abschnittsleitungen) in Germany should be amalgamated into a single operational section, that was to be lead by German KPD organiser

Wilhelm Knöchel. The Comintern decided the planning stage for the operation would be done in Amsterdam. From mid-1940, Knöchel with the assistance of Goulooze began to train the emigre group of communists in the Netherlands, to work in Germany as political activists, informers and instructors. Goulooze was able to obtain blank identity cards, along with official stamps to enable the KPD members who were in hiding, to interact with CPN members in Amsterdam and to travel safely to Germany.

In January 1941, the first Comintern instructor travelled to Berlin, followed by

Willi Seng, then Albert Kamradt and . On 9 January 1942, Knöchel travelled to Berlin. Goulooze arranged for everything that was published by the Comintern executive in Moscow, to be couriered to Knöchel in Berlin.

France

In Paris, Trepper's assistants were Grossvogel and Polish Jew

Hillel Katz, who was the group's recruiter. Trepper contacted General

Ivan Susloparov, Soviet

Military attaché in the

Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of ...

government, both in an attempt to reconnect with Soviet intelligence and locate another transmitter. Trepper came under the supervision of Susloparov who charged him with building an espionage network that targeted military intelligence. After passing his intelligence to Susloparov, Trepper started to organise a new cover company by recruiting Belgian businessman

Nazarin Drailly. On 19 March 1941, Drailly became the main shareholder in the

Simexco company, located in Brussels. Trepper also created a similar company in Paris that was known as

Simex and was run by former Belgian diplomat

Jules Jaspar along with French commercial director

Alfred Corbin. Trepper who used the alias ''Jean Gilbert'', a Frenchman was also a director of the firm. Both companies sold

black market goods to the Germans but their best customer was

Organisation Todt

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi. The organisation was responsible for a huge range of engineering pr ...

, the

civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and

military engineer

Military engineering is loosely defined as the art, science, and practice of designing and building military works and maintaining lines of military transport and military communications. Military engineers are also responsible for logistics ...

ing organisation of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. The two firms gave Trepper access to industrialists and businessmen, but he was always careful to remain in the background in any deal but ensured that suitable questions were asked and that he dealt only with people in responsible positions.

Around 1930, Comintern agent

Henry Robinson arrived in Paris and became the section leader for Switzerland, France, and Great Britain, to conduct intelligence gathering operations against France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Great Britain. In 1930, Robinson became director of BB-Aparat (intelligence department) of the French Communist Party and the

International Liaison Department (OMS) of the Comintern in Western Europe.

Towards the end of 1940 and during all of 1941, Trepper searched for a radio operator in France, as a backup communications link should Makarov be arrested. In the spring of 1941, the Polish couple, Harry and Mira Sokol were recruited and trained as radio operators by Leon Grossvogel.

In September 1941, on orders from Soviet intelligence, Trepper met with Robinson in Paris. While Trepper was an agent of Red Army intelligence, Robinson was a Comintern agent. Robinson and the Comintern had lost prestige with Stalin, who suspected it of deviating from Communist norms. Robinson was also suspected of being an agent of the

Deuxième Bureau

The Deuxième Bureau de l'État-major général ("Second Bureau of the General Staff") was France's external military intelligence agency from 1871 to 1940. It was dissolved together with the Third Republic upon the armistice with Germany. Howeve ...

, so subsequently he was in ideological conflict with Soviet intelligence. Therefore, it was unusual for two senior agents to meet, but an exception was made as it was felt by Soviet intelligence that Robinson's extensive contacts could help Trepper build his French networks.

Prior to September 1941, Robinson sent his intelligence via a cutout who took them to the Soviet Embassy in Paris, where they were conveyed by

diplomatic pouch to the Soviet Union. After meeting Trepper, Robinson arranged to receive his messages via Makarov. When Makarov was arrested in December 1941, it resulted in a complete loss of communications for the Trepper and Robinson networks. Trepper was unable to make contact with Soviet intelligence until February 1942, when he learned from Robinson of a radio transmitter that was being run by the French Communist Party in Paris and was ordered to take charge of Robinson's network.

The Sokols began transmitting in April 1942, in a house at

Maisons-Laffitte

Maisons-Laffitte () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the northern Île-de-France region of France. It is a part of the affluent outer suburbs of northwestern Paris, from its centre. In 2018, it had a population of 23,611.

Maisons-Laf ...

, to the north of Paris. After the arrests in Belgium by the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle, the Sokols became the group's sole radio operator. Because of the high volume of intelligence being sent, their transmissions were detected by the Funkabwehr. On the 9 June 1942, the Sokols were arrested at the house. After the Sokol's arrest, Trepper switched to using Wenzel's transmitter in Brussels. However, that connection only lasted slightly longer than one month, as Wenzel was arrested on 30 July 1942. Trepper then used a transmitter belonging to the French Communist Party, to forward his reports. Pierre and Lucienne Giraud were used to courier the reports between Grossvogel and the French Communist Party in Paris. In the autumn of 1942, Trepper authorised Grossvogel to establish a new station at a house in

Le Pecq

Le Pecq () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the center of Paris.

Geography

The commune of Le Pecq is located in a loop of the Se ...

but the transmitter failed to work. The Gestapo arrived shortly after the group was established and discovered the transmitter buried in the garden.

In December 1942 Robinson was arrested in Paris by the

Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle. Trepper and Gurevich, were arrested on 9 November 1942 in

Marseilles

The seven networks

Trepper directed seven networks in France and each had its own group leader with a focus on gathering a specific type of intelligence. Trepper constructed them in a manner so that they were independent, working in parallel with only the group leader having direct contact with Trepper. Regular meeting places were used for contact points at predetermined times and these could only be set by Trepper. This type of communication meant that Trepper could contact the group leader but not vice versa and stringent security measures were built in at every step. These were as follows:

:

Switzerland

Rote Drei

The

Red Three (German: Rote Drei) was a Soviet espionage network that operated in Switzerland during and after World War II. It was perhaps the most important Soviet espionage network in the war, as they could work relatively undisturbed. The name ''Rote Drei'' was a German appellation, based on the number of transmitters or operators serving the network, and is perhaps misleading, as at times there were four, sometimes even five.